8. A Framework for Adopting Innovations

This chapter provides a framework and tools for progressing innovation from its early beginnings as an idea to its successful implementation into the operations of an organization. The Innovation Pathway describes the six stages of this journey. Next, we’ll concentrate on the adoption of innovations and propose an Innovation Adoption Factors Model that describes the six areas or domains that need to be considered and mastered in order to persuade individuals to make the decision to adopt the innovation. We’ll then break down the six domains into 18 factors and describe each of them. The factors become the basis for an adoption guidebook that can be used for evaluation and planning purposes. The chapter concludes with an application of the model to one of the healthcare adaptations proposed in the book through a hypothetical case study.

The Innovation Pathway

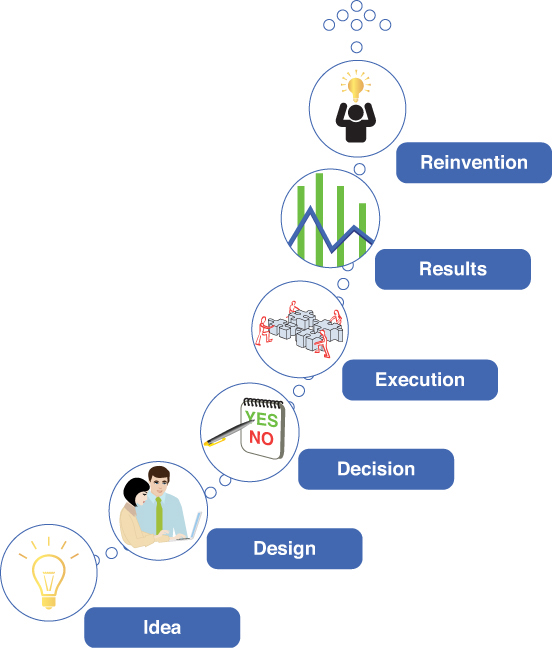

The pathway from an idea to its ultimate realization as an operable innovation is illustrated in the Innovation Pathway (see Figure 8.1). The pathway is made up of six stages, including idea, design, decision, execution, results, and reinvention. The stages are mostly linear, with the success of a given stage conditional to the passage to the next one. Failure at any stage extrudes the innovation from further development.

The starting point of the pathway is an idea. President John F. Kennedy exalted ideas. He said, “A man may die, nations may rise and fall, but an idea lives on.” Ideas can be many things, such as new knowledge that emerges from research, creative insights that come from thinking out of the usual mental models, or the collective wisdom of people working together to solve a problem. Ideas are often the backbone of innovations.

Ideas need to be converted into a plan of action during the design stage. This is the time to make the case that the innovation’s “theory of action” will accomplish intended results. In healthcare, the end result is usually framed in terms of saving lives and dollars through the actions of providers, payers, and life science companies. The innovations can include prevention or treatment guidelines, ways to change patient behaviors, payment and delivery system reforms, and more.

The decision stage involves decisions of individuals within an organization to adopt the innovation; that is, to accept or reject the plan. This stage requires facts, arguments, understanding of social and organizational context, communications to test the ideas and the plans, and last, but not least, leadership and management skills to bring the innovation over the finish line. Most ideas do not pass through the adoption membrane. Machiavelli said, “There is nothing more difficult to plan, more doubtful of success, nor more dangerous to manage than the creation of a new order of things.” In healthcare it is frustrating that even programs of demonstrated worth take a long time to be adopted, if ever.

The next stage is execution or implementation. Goethe noted in the eighteenth century, “To put your ideas into action is the most difficult thing in the world.” Implementation is certainly about following the design rule book in carrying out all the required process steps. It includes the need to fit the design prescription to the local needs of the organization, and this can involve a good deal of adaptation. And underlying it all, Jeffrey Pressman and Aaron Wildavsky, in their landmark book, Implementation, say, “Implementation is a struggle over the realization of ideas.”

The next stage is results. Stakeholders need to understand performance in order to make adjustments in the design and operations so that it becomes institutionalized, altered to fit the changing needs of the organization, or discontinued. More often than not, ideas get stuck in the pathway and do live to fight another stage. And implementations of complex programs suffer from innumerable snags in delivery of the program and most fail.

The last stage is reinvention. Reinvention is important and is not a failure of intent to implement a plan “as written.” For example, one might think that clinicians would adopt clinical guidelines, developed by their professional organizations, as is. But success might depend on not getting the full loaf and instead adopting a local version that works in a particular context. Hopefully, all innovations evolve and change through a learning and improvement process. The conclusion of Pressman and Wildavsky’s book on implementation speaks to an ongoing cycle of innovation. They said, “Implementation is no longer solely about getting what you once wanted but, instead, it is about what you have since learned to prefer until, of course, you change your mind again.”1

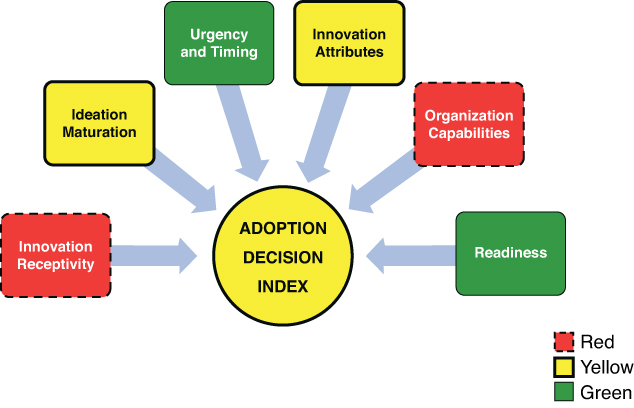

Innovation Adoption Factors Model

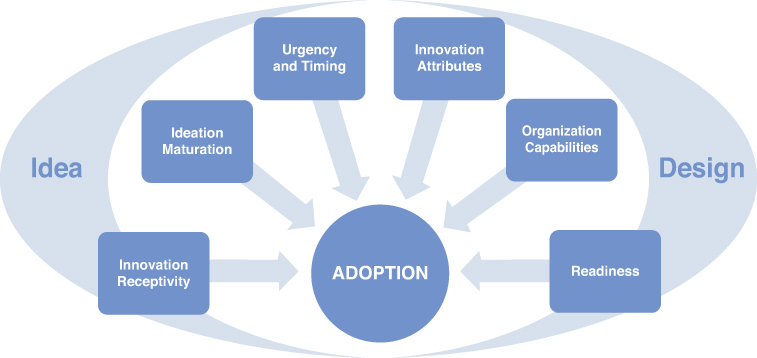

The Innovation Adoption Factors Model (see Figure 8.2) is a high-level map of the six domains that influence the likelihood of adoption of an idea or a design. Adoption is considered at the Decision stage of the Innovation Pathway. These six domains are composed of 18 specific factors, which are described in the next section.

Note that the overall model and its domains and factors are adapted from the extensive work of a number of researchers and policy experts in the innovation diffusion field, including Everett Rogers on diffusion theory,2 William Eggers and John O’Leary on getting things done in government,3 John Kingdon on agenda setting,4 Yeheskel Hasenfeld and Thomas Brock on policy implementation,5 Pressman and Wildavsky on program implementation,6 Malcolm Gladwell on the tipping point model of change,7 and Paul Plsek on complexity theory.8

Adoption is about making a decision to activate an innovation into practice. The process of adoption is largely about collecting, processing, and evaluating information to understand the innovation and to reduce uncertainty in relation to its pros and cons.

The model is composed of two halves. On the left side is the idea stage and on the right is the design stage, each with its respective factor domains. At the successful completion of these two stages, meaning that the 18 factors have been addressed, a recommendation for a decision can be considered by potential adopters.

Adoption Domains and Factors

This section provides a description of each of the 18 adoption factors. The factors are presented as rating checklists that can be used in evaluating the adoptability of the Key Healthcare Adaptations described in the previous chapter for one’s own organization. A case study at the end of this chapter provides an example of using the factors for decision making.

Idea Stage

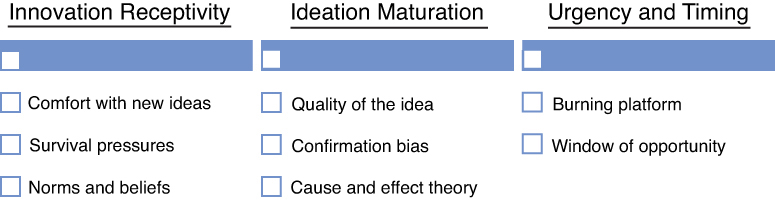

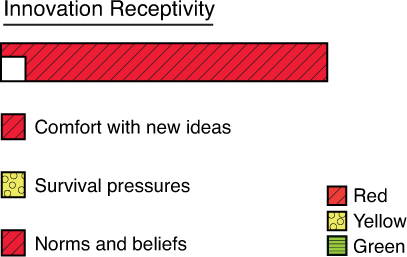

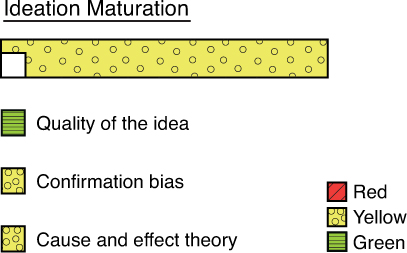

The idea stage includes the domains of innovation receptivity, ideation maturation, and urgency/timing (see Figure 8.3).

Innovation Receptivity

Innovation receptivity includes the factors of the organization’s comfort with dealing with new ideas, its survival pressures, and its existing norms and beliefs.

Comfort with New Ideas

Some organizations thrive with change and some shrink from it. Andrew Pettigrew, Ewan Ferle, and Lorna McKee, in their book Shaping Strategic Change: Making Change in Large Organizations, coined the phrase “receptive context” to describe the degree to which an organization is comfortable with change and new ideas.9 Organizations with high receptive context are continually “ripe” for change and adopt new innovations relatively quickly. Other organizations with low receptive context, which are confronted with the same challenges and are aware of the innovation in the same way, lack the will or ability to implement the innovation. This is really the metaphorical case of whether the land is fertile, arable, and moist enough to grow the seed.

Don Berwick, the founder of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, suggests that there are cultures that can encourage and support or discourage and impede change.10 For example, a nurturing environment would reinforce and reward the work of “boat-rocking” innovators and offer them security for the inevitable failures that are part of the work of experimentation. A penalizing environment takes issue with these “troublemakers” and spreads the message that others should do so as well, resulting in a marginalization of this key talent.

Survival Pressures

Innovations take energy and can be an opportunity cost that displaces other more important organizational priorities. For example, a health plan that is devoting lots of energy to compliance issues of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) or to replacing a legacy system data warehouse might not have the patience or tolerance for new ideas. Similarly, an organization that is just getting by financially and has limited resources might not be able to invest time and money into the consideration of innovations. Of course, organizations that avoid innovation because of chronic survival pressures might set themselves up for a death spiral of diminishing capability to innovate. The consequences of inaction could become very clear at some point, and this awareness might rearrange priorities for reconsideration of the innovation.

Norms and Beliefs about Change in General

Existing norms and beliefs of individuals, organizations, and industries affect how innovation is regarded. Healthcare is a conservative industry due in part to some ingrained beliefs from medicine. For example, the Hippocratic oath includes the famous phrase primum non nocere, or “first do no harm.” To this day, this is a fundamental principle for medical services. The twenty-first-century translation can be stated as “given an existing problem, it may be better not to do something, or even to do nothing, than to risk causing more harm than good.”11 Similarly the phrase “It’s better to be safe than sorry” reinforces the inclination to be cautious and to fend off legal suits. These beliefs can lead to an overestimation of the risks involved with new ideas and innovations and result in stifling them. Similarly, doctors are very autonomous professionals whose norms include self-reliance and resistance to imposed ideas.

Ideation Maturation

The ideation maturation factor is about developing a sound idea and includes the quality of the idea, resolving confirmation bias, and demonstrating a clear cause-and-effect theory of how the innovation produces change.

Quality of the Idea

The idea needs to be well formulated. It should emerge from good theory, be evidence based, supported by converging ideas in the literature, and logically developed with good critical thinking. If it passes these hurdles, it enters into what Kingdon refers to as the “primordial soup” of ideas and is ready for further debate to eventually be considered when just the right combination of circumstances arises.

A new, innovative idea involves a creative thinking process. Involving a wide circle of individuals in the creative process, and especially those who will be involved in deciding on and implementing the innovation, is critical to the maturity of the idea. Sometimes the best ideas come from out of the blue, for example, from another industry, and the initial intrigue needs to be supported by its logical linkage to healthcare. Sometimes they come from the deliberate work of science and research. In this case, a need/problem is recognized, hypotheses are formulated to test it, and solutions emerge from the findings. However the idea emerges, the quality of it sets the stage for everything else that follows in the Innovation Pathway.

Confirmation Bias

Eggers and O’Leary refer to the seven deadly traps that can bedevil any important change effort. The first is the Tolstoy Trap. They refer to this as the notion, attributed to Tolstoy, that “we see only what we are looking for often by staying blind to what is in front of us.”12 This is also referred to in the research literature as confirmation bias, which is a cognitive bias in which people seek out information that supports their beliefs and ignore all the rest. It is a very powerful bias, possibly related to a basic human need to be right and avoid embarrassment, as well as to avoid conflict. However, it is a big threat to critical thinking and the logical development and full expression of ideas. The antidote, the way to resolve the trap, is to constantly and actively challenge one’s thinking, to be humble about one’s knowledge, and to invite all voices, especially contrary ones, to offer a point of view and evidence. Also, it is a wise strategy to engage people in idea generation because there is a preference to favor ideas that one has been involved in generating.

Cause and Effect Theory

The idea must be such that the innovation (X) will lead to the intended results (Y). This is about the potency of theory and the model and not about the implementation of the innovation, which is quite another worrisome matter in terms of achieving Y. The steps must be clearly articulated and lead eventually to clear technical specifications and details on how to carry them out. When there is technical uncertainty about cause and effect, other factors can dominate the discourse about the innovation, such as ideological and political issues.13

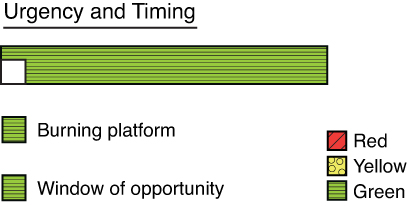

Urgency and Timing

The urgency and timing domain addresses whether there is a burning platform for change that the idea is aligned with and that there is a window of opportunity within which action is possible.

Burning Platform

Organizations face many demands and give attention to the highest priorities. Getting on the radar screen can be difficult for a new idea, depending on its potency and the status of factors discussed earlier; for example, receptive context. A burning platform provides compelling information that the status quo is dire or changing dramatically and that the current ways of doing business are not up to the challenge and a new solution is needed. If a burning platform is not established, it might be impossible to get the attention of key decision makers regardless of the merit of the proposed innovation. If attention is gained, the innovation must be shown to align with the burning platform.

Window of Opportunity

Kingdon refers to the window of opportunity as a time period during which change can occur and ideas can be considered. For example, in the political context this can be the first year of a President’s second term. In healthcare, a time frame might be imposed by a regulatory requirement, or a change in leadership, or funds that become available at a certain time. The window of opportunity is more than a time frame. It is a coupling of the burning platform, the innovation under consideration, and the right “moment.” In other words, when the iron is hot, bend it.

Design Stage

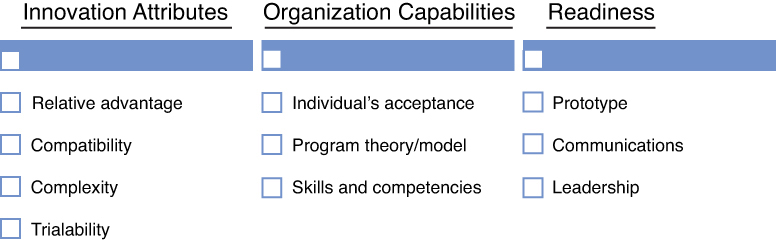

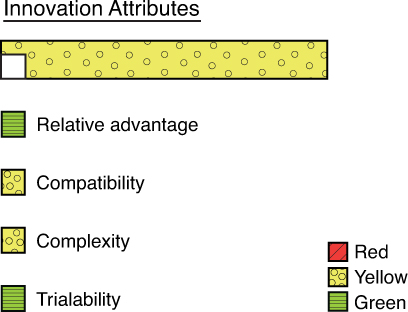

The design stage includes the domains of innovation attributes, organization capabilities, and readiness to position the innovation for adoption (see Figure 8.4).

Innovation Attributes

The innovation attributes domain is very important and includes the key factors of the relative advantage of the innovation, its compatibility with existing processes and attitudes, its complexity, and its “trialability.”

Relative Advantage

Relative advantage is the degree to which the innovation is judged to be better than an alternative or the status quo. It usually addresses the measurement of the potential impact in financial terms, such as the return on investment. In healthcare it often addresses the impact of the innovation on health and healthcare with such measures as reductions in mortality, lessened disability, improved functioning, and decreased adverse events. It is considered to be the most important parameter for the acceptance of an innovation. Berwick states that the perceived benefit of an innovation predicts between 49% and 87% of the variance in the rate of spread of an innovation.14 (It should be noted that the rate of spread is different from the rate of adoption, but the magnitude of the importance of relative advantage is large in both cases.) If idea generation answers the question, “what is it?,” then relative advantage addresses the question, what is it going to do for my company?

Compatibility

Compatibility addresses the degree to which the innovation is perceived to be consistent with the ways of the adopter organization and individuals. It addresses these questions: Does the innovation fit in with the way we do things? Is it out of line with how we have done things in the past? Does it reflect our values? Is it aligned with an overarching strategic plan? Does it fit with existing information technology? Does it blend well with other programs; for example, does it support or hinder an associated program?

Complexity

This is the degree to which an innovation is perceived to be difficult to understand and use. The acronym KISS applies here and more generally to the selling and execution of any idea or product: keep it simple, stupid. Good marketing can simplify the idea of complex innovations. The innovation needs to be decomposed into the steps or processes to make it understandable. Overly complex designs might be difficult to comprehend by adopters and difficult to interpret for implementers. An antidote to saving on overly complex innovation is to adapt it in a simpler way without compromising its essential working parts.

Trialability

Trialability addresses whether the innovation can be tried and evaluated on a small-scale basis as a test before a full-scale rollout. This diminishes the potential risk of failure and subsequent embarrassment to the adopters. It provides more evidence on the potential worth of the innovation to help sell it and complete the adoption of it. Most innovations can and perhaps should be sold as incremental stages with advancement to the next phase contingent on the results of learned experience to that point. However, there are risks to an incremental approach. For example, the results might not be statistically compelling on a small-scale test (small sample size), and the early phase of implementation might not have worked out all the kinks, whereas a longer period might be more indicative of the true functioning of the innovation.

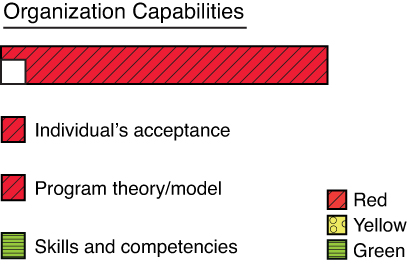

Organization Capabilities

The organizational capabilities domain includes individuals’ acceptance, whether the organization can deliver on the program theory, and whether the innovation is a complete or partial solution.

Individual’s Acceptance

The decision to adopt an innovation is made by an individual or a group of individuals in an organization. For an analytic innovation, the decision can be made by a manager of purchasing or all the way up to the executive committee of the board, depending on the investment size, risk, and importance of the innovation. After an adoption decision is made, it is expected to be carried out by the staff. It becomes a management priority, tools and educational packets are provided, performance is monitored, and the intended results are expected.

However, the process is complicated. The success of an innovation is usually not determined by management fiat but by the decisions of many individuals on whether they want to change relative to their own values and needs and organizational politics. For example, a hospital administrator decides to buy a new application for the electronic medical records system that issues alerts when doctors do not follow guidelines for ordering imaging tests. However, individual physicians will decide whether to pay attention to the alerts and change their behavior. It could be that they have alert “fatigue” and regard the alerts as distractions not worthy of their attention. Putting teeth into physician compliance by the hospital administrator sending a “reminder” note or docking pay might lead to more resistance from the doctors, who might resent a top-down approach to change that threatens their autonomy.

The reality might be that healthcare is a complex adaptive system that does not respond or adapt well to a linear, rational, mechanistic, and command-and-control management approach. Plsek states that “a decision to change is ultimately made by individuals in a complex system according to personal mental models about such things as the benefits and risks associated with the change [for them].”15 This factor highlights the need to include information about the likely acceptance of the innovation by individuals into the adoption decision. After all, if individuals are going to resist it with force, why go through all the trouble? When it comes to innovation, the engagement of individuals is more than “buy-in.” It has to be genuine, be continuous throughout the Pathway process, and involve a high degree of communications.

Program Theory/Model

Two aspects of innovations are discussed in this book. The first is the analytics component. This can be a specific predictive model, the use of external data, or a new initiative to gather more information on customers. The analytics component supports the programmatic intervention. Both components of the intervention need to function well on their own and in synchrony with the other. An example is the Health Improvement Capability Score. This score provides vital information on a patient’s capacity to respond to treatment in terms of their “activation” and the social forces that work against their getting better. The analytics solution is forthright and doable. It can be a huge success, but the intervention fails. Why?

The issue is whether the programmatic component can use/absorb the analytic contribution to achieve its goals. If there is not a sound programmatic model to effect a change, even with full accessibility to the analytics, the innovation will fail. Another example is the analytics contribution of BMI scores to identify people with premorbid risk of obesity and diabetes. The analytic task is, again, straightforward. But it is not at all clear whether the treatment team has a viable intervention model to reverse weight gain. It’s possible that the availability of these analytic assets will spur programs to develop better capacity. But it might be futile to deploy sound analytics technology when there are deficits in the “sociology.” If the model does not exist, is broken, and/or if there is not a pathway to improve it, then all the good analytics intentions and effort might be for naught.

Skills and Competencies

The organization must have people and technologies with the skills and competencies to carry out the analytic solution and the programmatic intervention. New innovations are likely to place new demands on individuals who are engaged with the adoption of the innovation. A good model and plan will not succeed if the right talent and technical supports are not available.

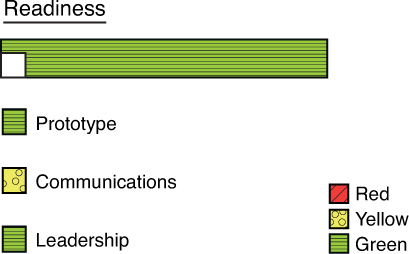

Readiness

The readiness domain includes evidence from small-scale tests of the innovation, communications to position the innovation favorably, and, last but not least, leadership.

Prototype

The trialability parameter previously described assesses whether the innovation can be tested on a small-scale basis. Prototyping involves the actual test-drive of the innovation. It involves building out the innovation design, or a portion of it, and testing it in relation to whether it is efficacious and implementable. It provides real-world evidence about the innovation and can be very influential in the adoption decision. Prototyping supports the notion of rapid experimentation to learn and adapt. And it roots out possible failure points by directly testing how the innovation might fail (better to “fail safe and fail fast”). It involves careful engineering approaches of flowcharting and process mapping to work out each step of the design. Prototyping facilitates what Rogers calls the “observability” of the innovation such that potential adopters can watch it in action and thus facilitate more discussion about it.

Communications

Rogers states that the diffusion process at its core is about communications. The communications are about new ideas and whether they are worthwhile to try. The communications are among people who share information in an effort to arrive at a mutual understanding. He asserts that most individuals do not decide to adopt an innovation based on facts and scientific studies but rather on the observations from other people (peers) who have tried it. Those who have been the first to try out an innovation are referred to as early adopters and can become opinion leaders who can have a great influence on peers. This suggests that ample interpersonal communications about the innovation make a positive contribution to the likelihood of adoption.

Communications can be facilitated through existing social networks that encourage the free exchange of ideas. Organizational roles that deploy communications well to convince individuals about the merits of an innovation include connectors, mavens, and salesmen, in Gladwell’s terms.16 A connector has many and varied relationships in the social system and can make introductions across boundaries and help to knock down barriers. Mavens like to spread ideas and act as information brokers who share ideas and help people solve problems. And salesmen are the “persuaders” who have a knack for making others agree with them.

Innovations can be packaged to make them “irresistible” to those considering them. And they can be packaged with the needed support materials such as documentation and user manual, to demonstrate that implementation concerns have been considered. Consulting firms are expert in creating “fashion consciousness” to increase demand for their engagement with clients; for example, the assertion that “big data” is the next wave.

Leadership

Leadership at the executive level is about creating the vision and executing a strategy to “get people from where they are to where they have not been,” in the words of Henry Kissinger. Succeeding at innovation requires leadership that creates an environment that welcomes and encourages new ideas and change, cuts through the confusion and uncertainty to be decisive, and then leads the organization to execute flawlessly. Ideally, the organization is a learning system that is constantly updating its mental models and making improvements. Without this executive leadership, the rate of adoption of new innovations is compromised.

In addition to executive leadership, there needs to be “boots on the ground” leadership that is instrumental in moving a specific innovation through the process and concluding with a handoff at the end of the project to the responsible parties who will embed it in the daily life of the organization. These leaders are sometimes referred to as change agents and they can be internal and/or external. Their primary role is to be an excellent networker and communicator across the multiple groups involved in the process. They help individuals see the burning platform for change and understand organizational needs and capabilities, organization gaps, and possible future states. They facilitate the full discussion of ideas and the refinement of the innovation proposed for adoption. After the innovation is adopted, they can help keep it on course through the early stages of implementation by unlocking resistance or adapting the innovation to make it more workable.

Case Study

This case study uses the Factors Model to evaluate the likelihood of adopting an analytics innovation by a hypothetical organization. The evaluation results can be used for planning purposes to develop a road map for adoption success.

The case involves a health insurance company that is concerned about the poor treatment outcomes of its Medicaid population. It is considering the adoption of the Health Improvement Capabilities Index.

Context

Description of the Analytics Innovation: Health Improvement Capabilities Score

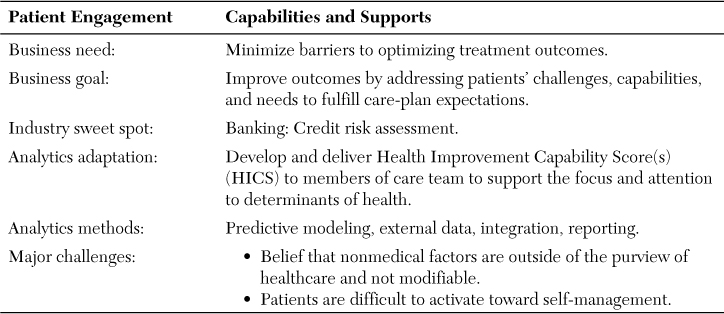

Table 8.1 outlines the key business issues and analytics challenges. The overall business need is to improve outcomes by overcoming nonmedical barriers to care. The business goal is to improve outcomes by addressing patients’ challenges, capabilities, and needs to fulfill care-plan expectations.

The healthcare analytics adaptation is derived from the banking and credit industries, which have refined the measurement of the risk of loan default. The analytics adaptation is the HICS. It is a composite score of the overall capability of a patient to succeed with treatment based on the individual’s activation and self-care skills and on the social determinants affecting the individual. The components of the overall score are also calculated. The scores would be made available to clinical teams in the patient’s medical record, as well as to other health support teams. The analytics methods include predictive modeling to determine the key factors related to poor outcomes, the collection of new data to populate the models, data integration, and clinical decision support reporting. The analytics capability is mature in most of these areas, with the analytical challenges including the capacity to build the new models and develop processes to collect new data. The major challenges in the adoption of the overall innovation is the perception that nonmedical factors are outside the purview of healthcare, that they are not modifiable, and that patients are generally disengaged from their own self-care.

Health Plan Context

The hypothetical health plan is 50 years old, regional, one million members, and marginally profitable. It has a 15% market share of the commercial market and a favorable reputation among employers. It is second to the Blues plan, which has a 60% share. It has a history of succeeding and failing as a staff model HMO. It has recently acquired a smaller Medicaid insurer to broaden its penetration into this expanding market. It is planning for partnerships with some provider groups to build an Accountable Care Organization pilot program. The new CEO envisions a future where the insurance component of the business will be complemented with new and more profitable business lines. The plan recently created a new position of Chief Analytics Officer (CAO), who will be responsible for leveraging its analytics assets to improve earnings by reducing medical costs and by selling medical information services. The states it serves are proceeding on schedule to develop their own health insurance exchanges and have accepted the ACA Medicaid plan for expanded enrollment.

Adoption Factor Evaluation

The readiness of the organization on the six domains is evaluated next. The dashboards include a rating on each of the 18 factors using the standard green, yellow, and red convention to indicate good, medium, or poor readiness for the factor. The component factors are combined into an overall adoption decision index. The component and index scores are displayed in an adoption decision dashboard.

The first three domains are for the idea generation stage.

Innovation receptivity scoring is displayed in Figure 8.5a.

The organization’s innovation receptivity is low overall, clearly in the red zone, and a significant barrier to change.

Its comfort with new ideas is in the red zone. The departing CEO held the position for 15 years and the culture of not rewarding risk taking is ingrained. The organizational structure is hierarchical and communications up and down and across it are very formal. New ideas are considered only during the six-week yearly budget cycle and the process is arduous and stern. Staff who rock the boat are considered troublemakers and their motives are questioned.

The analytics functions are dispersed throughout the organization, with much of the power and budget centralized in IT. There is a small medical informatics function that provides thought leadership. The few departments and functions that produce their own analytics are autonomous.

The organization has worrisome survival pressures. It failed as an HMO and merged with an indemnity insurer, and this history reinforces its reluctance to innovate and risk failure again. It has many compliance requirements from the ACA, as well as new state regulations. Its markets will be very active in the health insurance exchanges, and it must transform dramatically to become more customer-centric. The state has regulated that all plans serving state employees and residents enrolled in state insurance plans (commercial and Medicaid) must shift from fee-for-service payments to global payments. The state is also actively encouraging the development of Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) through regulation and incentives. All of these requirements placed new demands on the IT function such that it had to change its legacy data warehouse. A major, multimillion-dollar project is underway to do so.

A potentially positive development is that a new CEO was hired to radically reorient the organization to respond to its new opportunities and threats, including a reorg to flatten the organization. How successful the management changes will be in affecting the long-standing cultural predilection to shun change is unknown. History would suggest a red rating but the hope in new leadership edges it up to a yellow.

The norms and beliefs of the organization are conservative. As with all insurance companies, its core strength is in assessing risk. However, this strength has a flip side. It is also an impediment when it comes to thinking outside the box, which requires a high degree of comfort with the risks involved in such change. The organization is severely siloed into layers and functions, and it is hard to modify individual positions and socialize a collective perspective. Change is driven from the top and staff are expected to comply.

Were it not for the significant survival pressures, the hope that a new CEO will make a difference, and the external demands, any proposal for change at this time would be considered dead on arrival.

Idea maturation (see Figure 8.5b) is in the yellow zone overall.

The HICS idea has been well formulated and has been reasonably socialized. The leadership staff understand that patients need to be activated and supported in order to achieve better outcomes and that doctors need to be more attuned to factors that can compromise their medical intentions. There is agreement that a metric will help raise awareness and spur the development of programs to fill gaps.

In terms of confirmation bias, the new CAO is driving the idea. She has a strong bias toward population health. But some individuals do not get it, believe that it is a not an insurance function, and think it is far-fetched and in the category of “boiling the ocean.” Hence, they have not been predisposed to discuss the idea on its merits. The actuaries are a powerful voice in the analytics community and in the insurance business overall, and they have ignored the idea. The paradox is that the idea is all about understanding risk, which is at the core of their work.

The cause-and-effect theory is understood, notwithstanding the resistance previously mentioned. It is clear that social determinants and patient activation have an enormous influence on outcomes, and that it is possible to measure these correctly. What plagues the acceptance of cause and effect is whether the health plan can and should do anything about it. Is it the health plan’s role and responsibility to improve outcomes? If so, is it technically possible to change behavior and social conditions sufficiently to achieve some potency with the innovation?

The overall score for urgency and timing (see Figure 8.5c) is a solid green.

The burning platform is compelling and might ignite progress on other, lagging factors. A major driver is that Medicaid plans, state employee insurance plans, and ACOs (eventually) will be paid through global payments (also known as neo-capitation). This will reward health plans to lower medical expenses. If the actual medical experience is lower than the projected expenses reflected in premiums, the plan and its partners reap the profits. Also, if the plan can lower premiums due to its success in lowering costs, it will attract a larger market share. The states will also have a quality performance measurement system to monitor and pay for high quality. The ACA also provides grants through the CMS Innovation Center to improve outcomes, and this innovation qualifies.

Everyone understands that 40% of health functioning is attributable to personal behaviors and 15% to social factors. Even if the healthcare delivery system were to work perfectly, it would have a relatively modest effect on outcomes. The other behavioral and social levers are needed to optimize outcomes. The HICS is aligned with this need. And it is recognized that the HICS might also stimulate partnerships with provider groups and nonhealthcare organizations to create solutions that work.

The window of opportunity is also favorable for adopting the innovation. The health exchanges enroll members in the fall of 2013. The states require global payments in 2014. CMS grant proposals are due in six months. And the new CEO and CAO are looking for ways to provide value to the organization in a short time frame to demonstrate their value and retain their positions. The clock is ticking for action.

Next is a review of the design stage factors. The first is the important area of the innovation attributes (see Figure 8.6a). Overall, the innovation attributes are in the yellow zone.

An important reminder is that the innovation package is composed of two elements. The first is the analytics adaptation; that is, the HICS. The other is the program intervention. They are inextricably bound together, and both must function well independently and in synchrony to produce the intended results. In this section, the analytics adaptation is reviewed in terms of its innovation attributes. The program component is addressed in the organizational capacity domain.

The HICS is unique and there is no other option quite like it in healthcare today. So the determination of the relative value uses the status quo (without a score) as the comparator. A detailed staff study of the literature demonstrated that the potential for cost savings for the Medicaid population deriving from improvements in patient adherence to treatment plans—including prescription medications; patient behavior modification to reduce smoking, drinking, obesity, and lack of exercise; patient activation to improve health monitoring and social connectedness; and social supports to improve access to good foods, transportation, insurance, and legal aid—is significant and on the order of 33% per year. There are few studies that provide conclusive evidence on the actual effectiveness of interventions that have been put into practice. The consensus was that a reasonable estimate of savings could approach 20% per year with full implementation and benefits of the programs phased in over a five-year period.

The study concluded that the analytics component, the HICS, is a necessary foundation for the success of the intervention because it gives guidance to the physician and health team on how to direct their efforts. The report emphasized that what is measured is managed. They concluded that without the HICS, but with some education, the savings would diminish to less than 5%.

In terms of return on investment, the costs of developing the HICS include model building and the determination of the effects of different independent variables on outcomes and costs. The biggest challenge is collecting the data in the most cost-efficient way. One approach is to collect the relevant information directly from the patient as part of the initial workup and at regular intervals thereafter, not unlike the collection of clinical history information. The clinical history process gets reframed as a total health history, including patient capabilities. This could be administered through a self-service Internet application or an interview by an associate health worker. An alternative data source is from public records and is available from private data aggregators. The initial recommendation was to evaluate the publicly available data and test it with the models on historical data. This data-capture approach was judged to have lower impact on clinical operations and have lower costs. The ongoing costs of these data were estimated at $0.50 per member. Costs of storing and integrating the data with claims data was estimated at $0.05 per member. Initial costs for predictive modeling was estimated at $250,000. Overall, the ROI was considered sufficient at a 10% return per year and it was determined that a pilot test on a small sample of historical patients should be undertaken.

The compatibility of the HICS with the existing ways of the organization warranted a yellow signal at best because the idea is outside the realm of the usual insurance box and the data source is outside the comfort zone of standard claims and member data repositories. Additionally, the innovation would have to be implemented within a delivery system that might be harder to manage than within the health plan. (The health plan is actively looking for provider partners in order to have greater leverage on medical management in general.) A positive indicator is that the marketing department became very interested in the prospect of using the newly acquired data to improve its 360-degree view of the customer and could be useful in more refined approaches to microsegmentation.

Complexity also received a yellow signal because of the unknowns related to the new research and new data sources needed to make the HICS work. The HICS is not a difficult concept to communicate to providers. The analytics staff provided demos of what it would look like in the medical record in an attempt to simplify the understanding of the idea.

Trialability was feasible given the suggestion to first test the intervention on a historical sample. The suggestion was made to do a pilot test on one of the Medicaid diabetes programs, and initial conversations with the state Medicaid office were encouraging about their support for the innovation.

The organizational capabilities (see Figure 8.6b) to absorb and make full benefit of the innovation are in the red zone and are a major barrier to a favorable adoption decision.

In terms of an individual’s acceptance, the biggest concern is that physicians might not regard the innovation positively or support or use it. The emerging consensus is that it might not be the physician’s job to address nonmedical issues, and they should keep to the knitting of medical care and work with others on the multidisciplinary team to coordinate the use of the HICS. Ideally, there would be a team that evaluates all the relevant information pertaining to factors that limit a successful course of care which then coordinates appropriate actions. The health plan expressed interest in the work of Health Leads (described in other chapters of the book). Health Leads would receive the HICS on all chronic-disease patients and follow up with the patient as needed to get more information. They would develop a support plan, inform the medical team, and coordinate with other organizations in the social services network to attend to specific needs. However, the Health Leads concept is somewhat foreign to the usual delivery of medical care, and its benefit has not been demonstrated through research, which might engender skepticism among some individuals.

The program theory is sound. However, the program model is exploratory and there is early but sparse evidence of its effectiveness. A study on the experience of Health Leads to lower medical costs is underway and will speak to this component of the innovation. Emerging evidence demonstrates ways to improve medication compliance. Patient activation models are demonstrating success in reducing costs.17 And other ways to ramp up the level of patient engagement for self-care are emerging and hopeful. All of these findings were the basis of the consensus estimates of savings referred to earlier.

The skills and competencies for the analytic innovation are excellent. The new CAO is intent on demonstrating how analytics can improve earnings and sees this as a promising area. She is also considering the formation of an Analytics Center of Excellence, which will concentrate expertise from within and outside the company on fast-track, high-priority projects.

Readiness (see Figure 8.6c) overall is clearly in the green zone.

A conceptual prototype of the HICS includes a full delineation of its functional and technical specifications. Preliminary modeling identified ten dimensions of capability based on a multiple regression equation using selected external data as the independent variables and annual medical costs as the dependent variable. The model could not test the effectiveness of the specific program interventions based on historical data, but it did sort the sample into subgroups based on prescription adherence, which was a proxy for high-, medium-, and low-activated patients. The results confirmed the magnitude of possible savings when comparing the low-activation group with the high-activation group. The results were shared with focus groups of caregivers, and the feedback was used to improve the positioning of the HICS in communications.

Communications are a concern. The organization has been characterized as “top-down,” including the one-way direction of communications and the command-and-control management style. Lateral communications have not developed sufficiently and most individuals would rather eat alone at their desk than share food and ideas in an informal way with peers. The CAO is considering a new function of the center of excellence to build competence in research translation and the diffusion of innovations. Her first initiative in this regard is to identify opinion leaders, connectors, mavens, salesmen, and early adopters. She considers these skills as key success factors that represent analytic skills that are just as important as the technical expertise needed to build data warehouses, do computations, and provide reports. The CAO is clearly the change agent for the innovation.

The new leadership recognizes the imperative to innovate and to change the culture to encourage and reward change, new ideas, and risk takers. The CEO believes that the future of the health plan is in partnerships with providers and other community organizations to co-produce health and reduce costs. He also believes that one of the organization’s core skills is analytics and that it can drive the business toward needed transformation. In addition to the executive leadership, a change agent has been assigned the daily operational responsibility to get the HICS adopted and operating successfully.

The overall dashboard (see Figure 8.7) for the results obtained from the innovation adoption factors model indicate an overall cautious, yellow rating for the adoption decision index.

There is an equal balance among the six domains between red, yellow, and green, with the organizational receptivity to innovation and its capabilities to master change in the red. On the other hand, the timing and readiness to move forward at this time are clearly in the green. The areas in the yellow include the maturation and acceptance of the idea and the innovation attributes, both of which are very critical for the successful adoption of an innovation.

The dashboard results, including recommendations for bringing the innovation into the required green zone of the overall adoption index, will be presented to the executive management team.

Postscript

The CAO presented the proposal to the Executive Committee in January. The decision is still pending six months later. The initial reaction from the CEO was that the overall adoption decision index rating did not meet the threshold for consideration because it was in the yellow zone and the recommendations for improvement were not deemed sufficient. The proposal was tabled for two months.

The CAO followed up with the CEO in a one-on-one meeting to attempt to understand any underlying concerns. The biggest concern was that there were “just too many things going on.” The CAO prodded to understand more. One of the concerns the CEO expressed involved how to implement the program through its new Medicaid managed care plan, and he said that it was too early to “rock the boat.” He also confided that the medical director of the plan “had to go” in order to clear the way for physician communications and better partnership/conformity with management. He also emphasized that he was deep into making organization changes to flatten the organization and to change its character to be more responsive to employees and ideas. “This would take time.”

Most staff at the VP level, as was the CAO, would move on to other priorities at this point given the obstacles expressed by the CEO. But the new CAO was young and not inured to the traditional insurance culture. She had a vision and commitment about demonstrating the value proposition of analytics based on its contribution to improving outcomes in the post fee-for-service era. She refused to think of her function as a cost center.

She “worked” the company network to build relationships and not necessarily to sell the innovation. She built trust among her colleagues and the Medicaid staff, including a number of physicians. She placed a priority on doing some analytics studies that the physicians had proposed. She had an open door and people saw her as someone who would listen to their concerns.

The environment changed. The health plan bought another large Medicaid managed care plan. However, the medical experience of the newly enrolled Medicaid patients was higher than expected and the Board questioned the viability of the strategy and issued a reprimand to the new CEO. The (problem) medical director of the Medicaid plan resigned, and one of the doctors that the CAO had befriended got the chief medical officer (CMO) job. The CMO had spent most of her career in community health centers and was keenly aware of the challenges in treating patients with multiple social and support challenges.

The CAO, acting as a matchmaker, introduced the CMO to the executive director of Health Leads. There was good chemistry and excitement about developing a pilot program. Health Leads supported the HICS analytics and wanted to incorporate them into their present assessments with patients; they liked the idea of adding other, external data to improve the identification of concerns for treatment success. The CAO also wanted to bring a new partner into the mix to demonstrate quick wins. Medication compliance was a promising area given that compliance was in the low 40% range. They had meetings with the marketing director and chief innovation officer of CQS, a retailer and pharmaceutical benefit manager.

The CAO scheduled a meeting with the CEO to touch base and inform him of the possibilities of this new partnership. The principals met with the CEO. He was impressed with how the design of the HICS was increasing the likelihood of success and reducing risk, and he scheduled another meeting of the executive committee two months out to consider it.

In the meantime, the CAO wanted to bring the adoption decision index to green. She figured that the organization capabilities factors would easily go to green given the plan to partner with Health Leads and CQS. She also had the support of the CMO and his willingness to provide leadership to physicians and care teams to accept the HICS. On the program model factor she felt that the previous results were sufficient but wanted to close down this potential “exit point.” She worked with Health Leads to get funding from the foundation supporting it in exchange for the data on the performance of the program to help demonstrate its sustainability. This, in combination with CQS agreeing to provide funds for its aspect of the program and to share the prescription drug data, provided a good part of the operational funds needed to execute the plan.

She was skeptical about lifting the organization’s innovation receptivity scores higher because culture change was a long-term investment and would take more time than she had. It was entwined with the reorg and she did not want to touch it. She was able to increase the overall score to yellow based on her continuing work with building relationships throughout the network.

She was also able to improve the ideation maturation score overall to green by demonstrating the linkages in cause and effect more clearly and by spending some time with those actuaries who were particularly skeptical. She convinced them that the project was derived from the banking industry and that she understood and respected their analytics challenges much more.

She was also able to address concerns about complexity and compatibility by clearly demonstrating how the program would work with partners and with analytics staff throughout the organization.

At the meeting, she would be able to demonstrate that the adoption index is in the acceptable green area. She knew there would be other concerns that might emerge and that she needed a well-thought-out position on them. She sifted information from the network and realized two other challenges. First was that the CEO was on the ropes about losses with the Medicaid programs. She worked with the actuaries and partners to “sharpen the pencil” on the ROI from HICS and was able to demonstrate a contribution to margin of $1 million in 12 months and an increase in the trend line on profitability for the Medicaid product line. She investigated the requirements for a CMS grant and demonstrated that the health plan had a good shot at receiving $500,000 if they demonstrated capability with outcomes measurement and improvement with underserved populations through HICS. The second thing she realized was that the CEO needed a public relations lift, and she positioned the program as “doing the right thing” for the community, which would help with marketing and his favorability ratings. Marketing was delighted with the key messages and with branding the plan as the only one in the market dedicated to the health and well-being of all of its members. The CEO received front-page coverage in the local papers as the champion of the new campaign.

The meeting with the CEO and his executive staff and principals from Health Leads, CQS, the foundation, the Medicaid medical director, the chief actuary, and the chief marketing officer lasted less than 30 minutes. The decision was unanimous to move forward with the adoption contingent upon the CAO writing the successful attainment of the Medicaid margin expectations into her performance review.

From start to finish the decision process took six months. The CAO took a well-deserved weekend vacation in the Bahamas, where she wrote the road map for her next analytics innovation. She was very concerned about the rising costs of diabetes and the analytics opportunity to identify obesity through the calculation of the BMI through external data. Her “back of the envelope” estimate of ROI exceeded that of the HICS. And she went about the task of addressing each of the 18 factors fueled by the glow of the Bahamian sunset and her success with moving the organization to adopt analytics innovations.