2. Healthcare

Although healthcare has sophisticated, scientific analytics in its research about the nature of diseases, its application to the delivery of care and running the business has lagged.

Introduction

The healthcare industry is wonderful, unique, complex, and intransigent. It is wonderful because it deals with the most important asset an individual has: one’s health. We are distressed when we lose our health due to disease, accidents, or old age, and we are happy and thankful when we are relieved from pain, loss of function, and aloneness. However, the industry has many challenges in fulfilling these hopes related to achieving outcomes, efficiency, care delivery, and customer engagement. And it has many clear opportunities for breakthroughs in these areas and from other, less clear threats and challenges that can disrupt the business. The industry is very complex and has been intransigent to change on many fronts. Healthcare reform and market drivers are inducing change like never before.

Analytics can and must support the achievement of these business needs. Although healthcare has always had great scientific analytics in its research about the causes of diseases and the effectiveness of treatments, its application of analytics to the delivery of care and the running of the business has not been as successful. This chapter begins with a description of the unique and not-so-unique features and challenges of the healthcare industry. It ends with an overview of the current state of health analytics, including pointers to what can be learned from the business successes and related analytics sweet spots from other industries that are detailed in subsequent chapters.

It is a paradox that the success and failure of analytics in healthcare are related to NIH. The research conducted by the National Institutes of Health has led to remarkable discoveries. This book suggests that other industries can teach healthcare a lot through analytics and that a “not invented here” mind-set will blind the business of healthcare from opportunities within its grasp.

The Healthcare Industry Has a Unique Mission and Its Potential Contributions Are Great

A commonly expressed belief is “without your health, you have nothing.” If people experience pain, symptoms, and loss of functioning for a prolonged period, they cannot work or fully enjoy the pleasures of life. And when these are relieved, through either medical intervention or time, people are very thankful. The psychologist Abraham Maslow, in his pyramid/hierarchy of human needs paradigm for self-actualization,1 places basic physiologic needs at the base of the pyramid. Only after the basic physiological needs, such as food, shelter, water, and health, are satisfied can a person move up the pyramid to achieve safety, belonging, self-esteem, and the ultimate, self-actualization. Therefore, medical goods and services are viewed as necessities, like food, by most people and are valued highly.

What is health? According to the World Health Organization, health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.2 The healthcare system in the U.S. is primarily a sickness-focused industry. A multitude of distinct and unconnected systems address well-being in different areas, including public health, education, safety net, public safety, and many more.

Total U.S. health spending reached $2.7 trillion in 2011, amounting to about $8,500 per person.3 It accounts for a substantial 18% of the economy (GDP). The rate of growth in spending abated during the Great Recession years of 2009–2011 at 4% per year, probably because of lower consumption and, perhaps, improvements in the delivery of care. However, when put into perspective over the long term, health expenditures have risen by a factor of ten over the past 20 years, and it is doubtful that this recession reprieve will continue unless there is a substantial change in the underlying fundamentals. The U.S. continues to spend much more of its GDP on healthcare compared to all other countries—indeed, almost twice as much as other rich countries.

Although the U.S. government refers to national health expenditures in its statistics, the vast majority of expenditures pertain to health care. For example, annual hospital expenditures are approaching $1 trillion and physician services are more than $0.5 trillion.4 These two categories represent more than half of all expenditures. The next-largest area is prescription drugs, at 10% of expenditures. The remaining nine categories, including nursing home care, home health, government-sponsored health insurance, and investments in research, compose the remaining 39%. There is no budget category for prevention. Very little is spent on public health—only $82 billion or 3% of total expenditures—and this has not changed much over the past 20 years.5

Because of the necessity of providing care when people are sick, the seemingly intractable difficulty in controlling medical costs, and the collection of low tax revenues for governments resulting in flat budgets, healthcare has sucked up a disproportionate share of government budgets. For example, in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, state spending for health coverage increased 59% over the ten-year period ending in FY 2011. All other government human service budgets decreased. The hardest hit was public health, with a 38% decline. Mental health was down 33%, education down 15%, housing down 23%, human services down 13%, and public safety down 11%.6

As we will discuss shortly, the U.S. is not getting a good return on its heavy investment in healthcare as compared to other wealthy countries. Indeed, the outcomes across many domains are the worst in the U.S. This might be because the U.S. is really not investing as much in health as its peer countries. In fact, it ranks tenth.7 Elizabeth Bradley and Lauren Taylor looked at spending on social services such as unemployment benefits, pensions, family support services, and rent subsidies and added it to healthcare spending. When they compared the U.S. to 30 other industrialized countries on this combined measure of health spending, they found that the U.S. does not spend the most by a long shot.8 It spends about 29% of GDP on this bundle of health services. Other countries, such as Sweden, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Denmark, spent 33% to 38% of their GDP on health.

Additionally, they noted that for every dollar spent on healthcare in the U.S., it spends an additional 90 cents on social services. Yet in the comparison countries, every dollar spent on healthcare is complemented with $2 on social services. So a greater weight is placed on social services in these healthier countries than in the U.S.

As we will discuss shortly, the research is abundantly clear that social determinants are far more important in the production of health than the delivery of healthcare. The vast majority of physicians agree that unmet social needs are a direct cause of poor health. However, proposals for U.S. government spending for social programs bring out strong political opposition from the Right concerning support for a “socialist state” at the expense of “individual freedoms.” And individual freedoms do not often translate into behavioral changes to improve health. For example, personal behaviors directly related to obesity and violence are unique features of the American way of health and death.

First and foremost, health is at the core of the essence of life and is a vital foundation for the attainment of happiness and well-being in society. (The other industry that approaches these aspirational goals of well-being and achievement of human potential is the education system.) The mission of the other industries covered in this book, including retail, banking, politics, and sports, is relatively inconsequential:

• Retail makes, distributes, and sells goods, many of which are vital to well-being, including food, clothing, and transportation. The retail industry depends on and fosters a consumption society, and much of what is sold is nonessential, even frivolous. Americans love their shopping, derive a good deal of pleasure from it, and drive the economy accordingly through personal spending. Clearly if a wide spectrum of goods were not available, society would grind to a halt, but this is very unlikely in a vibrant market-oriented economy. The real limiting factor to achieving well-being from retail is the availability of money, which mostly comes from jobs, social supports, and good health.

• Banking facilitates the handling of money so that people can address their economic security. Retail banking facilitates the individual’s need to move, store, use, and invest money. Banking’s primary role is to handle transactions. But, as described in the preceding point, economic security is driven more by employment, social supports, and health status.

• Political campaigns boil down to voting. Voting is important for the full expression of democracy in a society in its choice of its representatives who subsequently make government policy. Voting is a fundamental civic right. But if an individual did not vote—and just under 50% do not vote in a presidential election—it would not limit one’s capability to live a satisfying life. If particular segments of society were not allowed to vote, as was the case with women and African Americans until the twentieth century, this could lead to social unrest and a poorly performing democracy and potentially to devastating economic problems. But at the individual level, voting does not contribute significantly to day-to-day happiness and well-being.

• Sports is about entertainment. Although many people spend lots of their leisure time watching sports and getting quite innervated about March Madness and the Super Bowl, it is primarily about leisure. Without sports, there would be alternatives to occupy people’s need for relaxation.

So health is a vital resource for people to survive and achieve well-being. Its purpose and mission are superordinate to other industries in terms of its contribution to society. Yet despite the fact that these other industries do not deal with life-and-death matters like healthcare, they can teach healthcare a lot. These other industries are very successful in business and have honed certain skills, techniques, strategies, and analytics that are often more refined than those in the healthcare industry.

The Healthcare Industry Has Major Challenges

The U.S. healthcare industry has five major challenges: suboptimal outcomes, voltage drop from science to the delivery of care, the need to move beyond a sickness system to achieve population health, inefficiency, and low customer engagement. These are described in the following sections.

Suboptimal Outcomes

It has been well known for quite some time that the U.S. does not achieve a good return on its extremely high expenditures for healthcare when compared to other industrialized countries. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) published a report, Health at a Glance in 2011,9 that ranked the U.S. at 28th among OECD countries on the most important measure of healthcare outcomes, life expectancy at birth. The U.S. was ranked lower than Slovenia and Chile and just above the Czech Republic, Poland, and Mexico. The U.S. gained 8.3 years in life expectancy over the past 50 years, which is a substantial gain when compared with life years gained in previous decades. However, when compared to other countries like Japan, the 8.3 years is just a bit more than half of what Japan gained. Life expectancy in Japan today is 5 years more than that in the U.S.

A report published in 2013 by the National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, U.S Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health,10 supported and extended these findings. The panel documented that the U.S fares the worst when compared to 17 high-income countries on nine critical health domains:

1. Adverse birth outcomes: infant mortality rate

2. Injuries and homicides: deaths from motor vehicle crashes, non-transportation-related injuries, and violence

3. Adolescent pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections

4. AIDS: highest incidence (HIV second highest)

5. Drugs- and alcohol-related mortality: years of life lost

6. Obesity and diabetes: highest rates and prevalence

7. Heart disease: death rate second highest

8. Chronic lung disease: higher than European countries

9. Disability: higher prevalence of arthritis and activity limitations

The panel also noted a surprising and disturbing finding that life expectancy is getting worse for people in the age group under 50 years in the U.S. as compared to other countries. Over the two-year period from 2006 to 2008, the number of years of life lost for this large group was higher than that in the other 16 countries. For men it was almost 1.4 years and for women it was 0.8 years—in just two years. Recall that it took 50 years for the U.S. to gain 8 years. Further, when the panel decomposed the data to understand what conditions were contributing the most to the life years lost in the U.S., more than half of the loss was attributed to causes not usually associated with healthcare, including violence and accidents. Note that the age-adjusted mortality rate for violence in the U.S. is much higher than that in all 17 countries and is six times higher than the lowest-mortality countries, including Japan, Austria, Norway, Switzerland, Germany, Denmark, Sweden, and Spain. The next-highest category contributing to the difference in loss of life years was perinatal conditions (mostly infant mortality), at 13%.

They suggested that in addition to known contributors to poor health performance, including lack of insurance, social and economic disadvantages, and race and ethnic disparities, there is a “health-wealth paradox” of a pervasive disadvantage that affects all Americans, including even the relatively well-off who do not smoke and are not overweight.

Voltage Drop from Science to the Delivery of Care

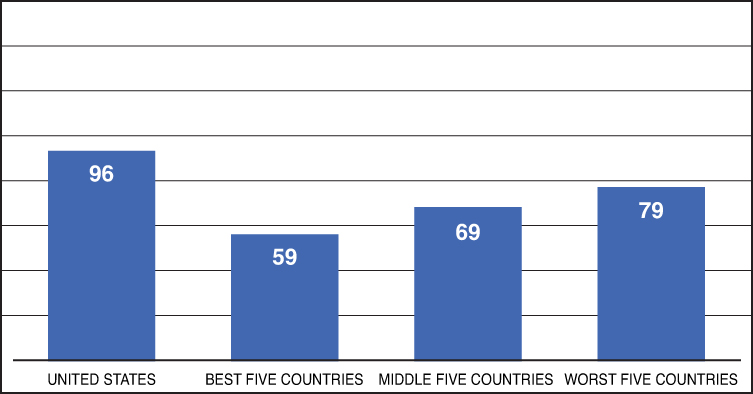

Important outcomes directly related to the delivery of healthcare are also the worst in the U.S. when compared to peer countries. One such measure is mortality amenable to healthcare. Included in this mortality rate are diseases with a well-known clinical understanding of its prevention and treatment, including ischemic heart disease, diabetes, stroke, and bacterial infections. In other words, the science is very clear on what needs to be done, and the premature mortality rate (for people under 75 years of age) is an important indicator of the success of executing on the science on what’s known. Figure 2.1, adapted from the Commonwealth Fund’s National Scorecard on U.S. Health System Performance 2011,11 compares the mortality amenable to healthcare rate compared to the averages of 15 other wealthy countries, which are nearly identical to the WHO research given previously. The U.S. rate of 96 deaths per 100,000 lives is almost 40% higher than the average of the best five countries, including France, Australia, Italy, Japan, and Sweden, at 59 deaths per 100,000. The U.S. is almost twice as high as the country with the lowest rate, France, at 55 deaths. Similarly, the U.S. rate is higher than the average of the middle tier of countries (69) and the countries with the highest rates (79). Further, the rate of improvement in the U.S. death rate over 10 years, between 1997 and 2007, is 20%, which is considerably less than the average for all other 15 countries, at 32%.

Source: Adapted from The Commonwealth Fund, 2011.

Figure 2.1 Mortality amenable to healthcare: premature death rates per 100,000.

The Commonwealth Fund also computes performance scores for five overall dimensions of a high-performing health system, including healthy lives, quality, access, efficiency, and equity, as well as an overall score. The U.S. gets a score of 70 out of 100 for “healthy lives” (the dimension most indicative of outcomes) and this score has fallen by five points since the 2006 Scorecard. The lowest score among these five domains is for efficiency, at 53. The overall score across all five domains is 64, which has been falling somewhat over the past 5 years.12

The voltage drop from the scientific bench to the clinical bedside (from research to practice) was documented in a now-classic study authored by Elizabeth McGlynn and her colleagues at the RAND Corporation, “The Quality of Health Care Delivered to Adults in the United States.”13 The research addressed the clinical adherence to recommended processes of care for 30 acute and chronic illnesses, as well as preventive care, with 439 indicators. Overall, the results showed that patients received recommended care about 55% of the time. They concluded that these deficits in the provision of recommended care “pose serious threats to the health of the American people.”14

The Need to Move Beyond a Sickness System to Achieve Population Health

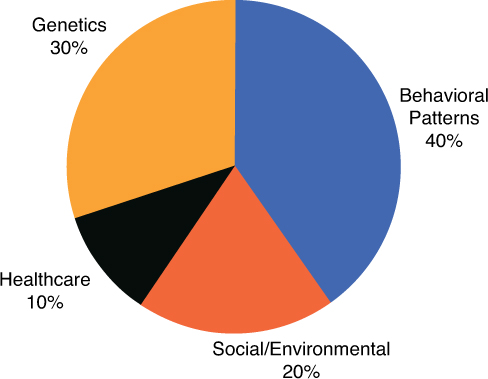

Health outcomes are a function of many factors. And the least important, despite its high cost in the U.S., is healthcare. The determinants of health have been well researched and documented in the “social determinants” literature. As Steve Schroeder said in his excellent Shattuck Lecture on improving the health of the American people, “even if the entire U.S. population had access to excellent medical care—which it does not—only a small fraction of [premature deaths] could be prevented.”15 The best distillation of the available data by McGinnis et al.16 indicates that the single greatest challenge and opportunity to prevent early death lies in modifying personal behavior. Figure 2.2 indicates that personal behavior accounts for more than 40% of health functioning, and shortfalls in healthcare account for only 10%. That is a fourfold difference. And the combination of behavior patterns with social and environmental factors adds up to almost two-thirds of all premature deaths.

Deaths attributable to behavioral causes amount to more than a million a year, including smoking at 435,000; obesity and inactivity at 365,000; alcohol at 85,000; motor vehicle accidents at over 43,000; and guns at 29,000.17 Changing behavior is the unrealized holy grail of producing better health, and it might be more influential in improving the health of the population than technological innovations.18

Social circumstances are also more influential than healthcare in determining health. And these are hard to change (including improvements in education, transportation, housing, and food). Schroeder suggests that a basic U.S. preference to value entrepreneurialism over egalitarianism, which results in inequality in income, education, and more, has definitive unintended health consequences.

What is clear is that the factors associated with good health go way beyond the traditional functions of the healthcare system. There have been accounts of doctors prescribing stimulants like Adderall and Concerta to underprivileged students to help them learn better and compete with students with more stable social environments, although these students do not have an A.D.H.D. diagnosis.19 This is an understandable, but unsavory, way to correct social inequalities. There are programs that work to supplement the fixation on sickness by providing a means for doctors to give “prescriptions” for transportation and healthy food. And the movement toward population health through accountable care organizations (ACOs) will place a greater emphasis on prevention and effective treatment.

The responsibility for the nation’s health well-being is dispersed through many public and private health systems and other social systems. It’s hard enough to get doctors within a practice or hospital or system to communicate with one another. Coordination across all these social and health systems seems almost inconceivable. The good news is that the U.S. does have experience and successes with organizing communities for better health as it did during the 1960s and 1970s and especially through the Great Society programs. Perhaps there will be a cyclical swing in U.S. politics back to a more progressive orientation to improving well-being for all through community-wide initiatives.

However, since social factors account for 15% of health and are extraordinarily complex and hard to change, a more proximate and potentially better return on investment would be in the primary area of behavior change and how to fully mobilize each individual’s ability to co-create their own health. We will return to this topic a number of times, through a variety of industry lenses, and with different analytic tools, as a possible breakthrough in improving health.

Inefficiency

Of all the performance metrics of the U.S. health system, efficiency is the worst. The Commonwealth Fund National Scorecard in 2011 gave it a score of 53 out of 100. It looks at indicators covering potential overuse; preventable emergency room use, hospitalizations, and readmissions; use of electronic medical records; and costs of care and mortality for specific conditions such as hip fractures and colon cancer and for multiple chronic diseases. Here are a few examples of worst performance metrics of the U.S. healthcare system relative to those of other countries:

• More duplicate medical tests

• More tests resulting from medical records not available at time of appointment

• ER visits for conditions that could have been treated at home

• Highest insurance administrative costs

• Lowest use of electronic medical records (except for Canada, 2009)

The data on variation on costs and outcomes has also been well documented by the Dartmouth Atlas20 on a wide variety of measures, including hospital and physician utilization, surgical procedures, intensity of care, care for chronic conditions, and end-of-life care. The Dartmouth data looks at regional and hospital variation and has been a major data resource to spotlight variation in clinical practices as it relates to cost and quality. Atul Gawande’s use of the Dartmouth data to expose waste and abuse of the fee-for-service system in McAllen, Texas, in his classic New Yorker article “The Cost Conundrum”21 ignited concerns about overuse in the U.S. healthcare system.

Finally, when the efficiency of the healthcare system is compared to the efficiency of other systems that address societal needs, such as government, finance, communications, transportation, and more, healthcare is rated the worst on two metrics. The first metric is a measure of system inefficiency as a percentage of total economic value of the system. Healthcare gets a score of 40%, higher than any other system. For example, on this metric communications is at 22%. The other measure is improvement potential as percentage of system inefficiency. Again, healthcare ranks lowest, meaning it has the greatest improvement potential with a score of 35% as compared to government at 27%.22 This corresponds well with many reviews that peg waste in the U.S. healthcare system at 30% or more.23

Low Consumer Engagement

If behavior is vitally important to improving health, engaging people is the first step, and then providing a good customer experience motivates, sustains, and satisfies them. But people have chosen, by and large, not to be engaged in healthcare despite the fact that they need to become genuine co-producers of health in partnership with their provider, payer, pharmacy, and other health system counterparts.

Customer experience can be measured. Forrester Research rates customer experiences across industries.24 It defines customer experience in terms of (1) meeting needs, (2) being easy to work with, and (3) enjoyability. Its 2011 survey results show that health plans/systems are dead last in the rankings among 14 industries, even lower than credit card providers and Internet service providers. Kaiser Permanente is the highest-rated health plan/system surveyed, with a ranking of 75 out of the 133 companies across all industries rated. Medicare is 102 and United Healthcare is close to the bottom of the list at 131.

Not surprisingly, retailers and hotels rank highest. They understand the need to satisfy customers in an industry that depends on repeat business. Also, insurance providers in other industries do much better than the healthcare insurance industry and rank fifth with an average score of 72%, as compared to health insurance at 51%. Their direct connection with the customer, as contrasted with the indirect connection through intermediaries in health insurance, might say a lot about the relatively higher regard paid to customers and the appreciation voiced by customers in their ratings.

Customer engagement going forward might get complicated in all industries. Because of advances in mobile phones, the influence of social media, and the consumer demand for simplicity, convenience, and transparency, there might be significant social change brewing that will turn the tables on conventional ideas about customer experience. Other industries are responding to this...healthcare is lagging.

Summary: Monetizing the Challenges

In summary, the challenges to the U.S. health system in relation to outcomes, efficiency, and customer engagement are huge, and the opportunities for improvement are also huge and could be the basis of competitive differentiation. The costs in terms of lives lost and quality of life are most important. However, if one were to monetize the value of closing the gap between present performance and benchmarks, the rough estimates are as given here:

• Outcomes

If the U.S. had the same mortality rate amenable to healthcare as the average of France, Australia, Italy, Japan, and Sweden, it would be about 40% less and save 118,000 lives a year. At the U.S. government’s estimate of the value of a life at about $7 million,25 this loss of life amounts to $826,000,000,000, or close to one trillion dollars.

• Efficiency

If healthcare eliminated all waste (midpoint estimate of 34%), it would save almost one trillion dollars a year, according to Berwick and Hackbarth.26 If healthcare were as efficient as the most efficient system, communications, it would be at least 50% more efficient than it is now, and this would save a half trillion.

• Customer Engagement

If the (average) health insurance plan performed like the (average) retailer, there would be a 61% improvement. Better customer engagement would increase market share and related profits. If one assumed a very modest increase in market share of only 10% related to significant improvements in customer engagement, this would result in the capture of 2.5 to 5 million new customers as a result of the increased number of people projected to be insured through the Affordable Care Act (25 to 50 million) and monetized at a total premium value of $28 billion dollars (based on average individual premiums of $5,650 in 201227). If 10% of the existing pool of people with insurance (100 million), or 10 million people, shifted plans, this would result in more than $50 billion.

The purpose of this monetizing exercise is to demonstrate the order of magnitude of possibilities, not to provide exact projections. Indeed, the savings are based on reaching the full potential relative to benchmarks, which is seldom accomplished given the complexities of implementation. However, if the healthcare system reduced waste by just half, that would amount to $500 billion. Similarly, understanding the value of life lost as a result of not executing delivery well is important even if it resulted only in achieving half the goal or $500 billion.

Healthcare Is a Very Different Industry in Many Respects

Healthcare is complex, much more so than most other industries. It is based on sophisticated research, is practiced by highly trained professionals, uses high-tech equipment, and delivers its products and services through multiple settings. It is often uncoordinated and unconnected. It is headed by an elite profession. It does not follow many of the market fundamentals of other industries.

The primary focus of most industries is on the customer for the simple reason that without the continued support of customers in buying the industry’s products and services, businesses could not compete and would go out of business. However, healthcare does not think of people as customers. It uses various terms to describe them, including patient, member, consumer, and citizen. This is partly understandable because the people who get treated, enroll in health plans, or buy medications are not regarded as the real customers.

A customer is defined as a person or an organization that buys goods or services from a store or another business. In healthcare, employers are the buyers of health insurance. Doctors contract with insurers. Pharmaceutical benefit managers make deals with employers. People do buy a lot of health and wellness products, and many go to doctors a lot and a minority are treated in hospitals. But when it comes to purchasing medical services, they usually pay only a fraction of the cost, use other people’s money (insurance), follow employer/government benefit rules on plan choice (if any) and “allowable” services, and mostly “buy” what the doctor orders.

In addition to limited options—for example, one can only go to the prescribed in-network hospitals or doctors—people cannot really make a choice at the point of service because they are often sick or in an emergency. For example, take the case of the person who is brought to the ER unconscious and the hospital assigns an expert trauma surgeon to operate. But the surgeon is out of network, and the patient, without having any choice, is billed a lot more than if the doctor were in network.

In addition to limited choice and fake money, both of which seriously compromise the basic requirements of well-functioning markets, consumers have little information on cost and quality to help with their purchasing decisions. Although public reporting of performance metrics in healthcare are forging the way for greater availability of quality and cost information to drive accountability and better performance, transparency in the healthcare industry is subpar when compared to transparency in other industries. Most people do not use the information for making choices, and most experts would agree that transparency’s true purpose is to publicly expose information to providers and insurers so that they can compete more vigorously. This is very different when compared to other industries. In retail, for example, customers do “show-rooming.” A customer goes to a store, checks out the product, pulls out the smartphone and compares prices from all other stores, and then makes a decision based on readily available price and quality information. It seems inconceivable that show-rooming will ever become a reality in healthcare. But it must.

The costs and outcomes of healthcare are largely driven by the decisions of intermediaries, not individuals, even though the latter pay for it directly out of pocket and indirectly through taxes and lower wages. As previously noted, employers and health insurers make many decisions on behalf of people. But the most important intermediary is the doctor who is responsible for most decisions related to a patient’s healthcare and directs about 80% of the costs related to care.

Even pricing is different in healthcare. Usually price is determined based on input costs, perceived value, and what the market will bear relative to the competition. In (commercial) healthcare, the price of services is negotiated between insurers and providers. Prices for the same CPT code for very common services can vary significantly across insurers and providers. For example, in a study by the State of Massachusetts28 on statewide payments for services across hospitals, the prices paid for an appendectomy (DRG 225) varied by more than 11-fold for a severity-1 stay and 16-fold for a severity-2 stay. Prices paid for each of the other selected DRGs varied less significantly, but in no instance did they vary by less than 300% statewide. Providers might proclaim that they charge more because they have better quality. But that is seldom the case. One of the major drivers of higher prices is the brand power of a provider group, sometimes referred to as “brand blackmail” that can extract higher payments from insurers.

Healthcare is heavily regulated and there are many business compliance requirements. Additionally, some features of the ACA will induce transformation of the industry as no market forces could possibly do. For example, the Affordable Care Act changes the marketplace for health insurance by legislating health insurance exchanges, making certain risk management practices illegal; for example, insurers cannot deny insurance because of preexisting conditions, and states will review health insurance rate increases for reasonableness. It also opens up the marketplace such that individuals can buy insurance from insurers directly from the exchanges. The CBO estimates that 25 million Americans will buy insurance on the exchanges. Others estimate that more than 70 million will eventually do so if an estimated 30% of employers stop offering coverage.29 This will require insurers to focus on “retail” customers, their members, and prospective members, in addition to selling to (wholesale) employers. Additionally, there are strict rules on privacy and sharing data, as with HIPPA. And there are regulations on bringing products to market that require evidence of safety, efficacy, and fair advertising.

Finally, all industries have their own norms and cultures. What might pass as “pulling the wool over the eyes” in retail marketing might not fit well with the perceived culture of the caring professionals in healthcare. However, it could be argued that the relentless provision of more and more diagnostic tests leading to unnecessary procedures is driven more to improve “revenue enhancement” than to improve the patient’s health. Similarly, the relentless onslaught of advertising for prescription drugs for newly profitable conditions—now the favorite is low testosterone in men, last year it was toe fungus, and of course there is the ever-popular erectile dysfunction—uses perfectly designed images and messages to sell lots of pills.

There are other aspects of the healthcare industry’s culture that are unique. Most people who go into the healthcare professions are more caring and dedicated to improving society than are those who enter careers that are more directly focused on commerce and profits. Additionally, there is a strict hierarchy of power and influence, from the doctor downward. There is a stubborn orientation to be provider-centric rather than patient/customer-centric on straightforward issues such as convenience and shared decision making. There is an inherent autonomy in the profession of doctoring that makes it particularly impervious to change. And there are special peculiarities of the business of healthcare, which are emphasized later.

Healthcare Is a Very Similar Business on Some of the Fundamentals

Healthcare is big business with national revenues for doctors and hospitals at almost $1.5 trillion in 2013. The size of the largest healthcare companies is impressive. Kaiser Permanente, an integrated delivery system and health insurance plan, has almost 9 million members/customers, 173,000 employees, 16,658 physicians, 37 hospitals, 611 medical offices, and operating revenues close to $50 billion in 2011.30 The largest health insurance company is United Healthcare Group, with more than $100 billion in revenues. The largest life sciences company is Pfizer, at $50 billion in total revenues.

However, despite these behemoths of the industry, most care delivered by the nation’s nearly one million doctors is performed in solo practices, and 37% is in small group practices of two to five physicians.31 Hospital care is delivered in nearly 6,000 hospitals. And the vast majority of care delivered in hospitals (87%) is in community hospitals with an average size of about 150 beds. Additionally, fewer than a third of the nation’s 6,000 hospitals are in a network that works together with physicians, insurers, and other community agencies to provide coordinated care.32

The healthcare industry has been characterized as a cottage industry by some. A cottage industry refers to establishments that create tailored products and services, usually in the home or in shops, and by families or solo craftsmen. The cottage approach is very different from a mass production approach. As mentioned earlier, much of the healthcare industry is composed of doctors in solo or small practices, doing their work in small offices, and in relatively small community hospitals. The industry is not coordinated or integrated to any large degree and is led by “dedicated artisans” (doctors) who overvalue autonomy and eschew any form of standardization that would certainly be required for “productionalized” medicine.33 This autonomy, reliance on intuition, and reluctance to seek feedback for improvement blunts the use of disciplined science in determining whether to embrace clinical guidelines or to adopt efficient business processes. For example, were it not for the meaningful use payment of up to $63,750 from Medicare and Medicaid to implement electronic health records (EHRs), most doctors would demur because they see it as a distraction to their office efficiency. This cultural DNA of practitioners defines the character of the industry and influences the performance of the business.

On the other hand, many (doctors) would argue that the business of healthcare has turned to market-oriented solutions implemented through corporate capitalism over the past 25 years or so. This, of course, is quite different from a cottage industry! This turn toward market-oriented solutions and away from government-oriented solutions happened in the 1980s as Americans, or at least the majority of their elected politicians at the time, decided that healthcare should be run by the same economic and business strategies that drive other industries. It was widely held that costs and medical inflation were out of control, that government solutions had failed, and that it was time for business solutions that were successful in other industries to be tried in healthcare.

For doctors, this has resulted in many forms of oversight, including contracts with managed care companies that resulted in monitoring of their economic and clinical performance along with increasing pressure to comply with standard clinical and business practices. Some market-oriented approaches became unpalatable to Americans, including policies on preexisting condition exclusions and high annual insurance premium increases. Thirty years later, government stepped in to reinstate government regulations to shape the insurance market with the Affordable Care Act. However, the healthcare industry is still largely a market-driven industry, despite the fact that Medicare and Medicaid payments by both the federal and state governments are about the same as employer and household payments for healthcare.34 Whatever the funding source, care is mostly provided in the private sector and through private health insurers.

Previously, we concluded that the healthcare system continues to be very inefficient and ineffective relative to other systems/industries and relative to its own standards. On the other hand, the healthcare industry overall is profitable and has done well for its investors. Healthcare (including insurance and care delivery) ranked 14th in profitability among 35 top industries with return on assets of 3.7%, and 19th in terms of profit growth at 8.4%, in 2009.35 (The most profitable industries were mining and oil production at 19.8% and pharmaceuticals at 19.1%.) The largest healthcare company, UnitedHealth Group, realized more than $5 billion in profits in 2011, an 11% increase from 2010.

What are we to make of this paradox? How can an industry be so successful from a business point of view yet so subpar on addressing key business challenges? It depends on what the business objectives are. It is not the responsibility of business, per se, to attend to society’s needs. It survives by responding to business needs, which are not always aligned with society’s needs. It stays in business to the extent that it satisfies shareholder/investor expectations to achieve good earnings. First and foremost, business wants to do well for its investors, and secondarily it wants to do good for society.

There are many examples of healthcare business practices thwarting the public good, including the aggressive lobbying of Congress to extend patent or pricing protections for a pharmaceutical firm at tremendous expense to society,36 the perpetuation of a fee-for-service payment system that often produces more volume and revenues than effective outcomes, and the marketing of “me, too” drugs that provide little incremental value while ignoring research and development on orphan drugs to benefit the suffering of people with rare diseases. Governments attempt to step in to address the public good and create a fair economic playing field for the market to achieve societal goals. For example, the State of Massachusetts has enacted global payments for all state-funded programs and expects the private sector to follow suit. The fact that market-driven industries, all of them, do what’s important to their shareholders first is not an earth-shattering insight. But what is paradoxical is why some healthcare companies have not taken on the challenge to bridge the gap to provide breakthrough performance to improve care and thereby achieve competitive differentiation.

All businesses in all industries survive and can thrive by creating a competitive advantage in the marketplace. The core of the advantage is the ability to meet customer needs more effectively with products and services that customers value more highly or to meet needs more efficiently through lower costs and prices to customers. Companies like Walmart and Southwest Airlines are good examples of low-cost providers. Good examples of companies that have differentiated themselves on the basis of high quality, added performance, design, or technical superiority include Apple for innovative products and design, Rolex or Armani for brand prestige, and Mercedes for engineering prowess.

In healthcare, price is very important when it comes to insurance because employers tend to pick the lowest-cost options (or subsidize employees’ co-share of premiums for the most efficient plans so that they follow suit in selecting low-cost plans). Employees also tend to use price as the major factor in choosing a plan if they have any choice at all. They presume, probably rightly, that there is no true “quality” differentiation among healthcare insurers in a given market area. When it comes to providers, “prices” are negotiated with insurers largely based on brand “power.” Some healthcare providers get better prices simply because they can...because they have market power; for example, a provider might do so by threatening to not accept an insurance carrier and thereby deny access for its members to its highly branded hospitals unless its price demands are met. Utilization of providers by patients is not usually a function of price or quality since neither is known by the patient, although there is wide variation in what insurers pay providers and what providers bill patients. Choice of hospital and doctor is usually constrained by network configuration. Often, patients simply pick the doctor who lives closest to them and speaks their language.

There are many shifts underway in healthcare, driven by both government and market forces, which can be exploited to achieve market differentiation that can supersede competition on price alone:

• Retail transformation: Healthcare reform and other forces are requiring insurers to change their orientation on who the customer is. They will need to go from a wholesale business-to-business approach with employers to a retail business-to-customer approach with individuals. This will place emphasis on pleasing the retail customer with good service, transparency on price and performance, and radical personalization to satisfy the customer. These have not been strong skills of health insurers. Winners can emerge to earn greater market share.

• Delivery system changes: The movement toward ACOs is moving forward with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) offering a number of pilot programs. Related to ACOs are medical homes, payer and provider blending/merging, and full actualization of patient centered care. These innovations can lead to efficiencies to reduce price and improve quality.

• Payment changes: The move to global payments is very important to diminish the wasteful sequelae of the fee-for-service system. If the theory is right, and it is implemented well, it should lead to efficiencies to improve outcomes and lower costs.

• Focus on outcomes: Related to payment and delivery-system changes is a focus on outcomes. Can you imagine if one integrated delivery system could state with certainty that it can prove that they provide better outcomes than their competitors for various conditions? This is different from the publicly reported scorecards that include arcane measures, at least in the eyes of regular people, such as the rate of administering beta blockers for heart attack.

In addition to these known clinical and business opportunities in healthcare, there are future unknowns that can fly under the radar screen and can cause considerable disruption. These were referred to in Chapter 1, “Overview,” as Kodak moments of 2012 and indicate the need to scan for game-changing technologies that can either make the business obsolete or make it absolutely untouchable from a competitive differentiation point of view. These potential game changes are as follows:

• Behavior change: The greatest unmet challenge in health production is individual-driven behavior change. Closing this gap will result in great strides in prevention, care management, and outcomes.

• Democratization: Healthcare is provider-centric. Web 2.0 and social media change the locus of control, emphasizing the power of networks, and how care can be purchased, evaluated, and modified. This might provoke the need to be people-centric and for organizations to take their lead rather than prescribing procedures and rules to follow.

• De-medicalized health systems: Medical care is a small contributor to health. New organizational forms of health production will be induced as cost pressures grow and outcomes lag. For example, in addition to medical homes, there might be health houses.

• Predictions: Use of huge volumes and different, but highly relevant, types of data from within and outside the industry will lead to significantly better predictions to inform an array of strategies and decisions.

• Mobile: People have grown a new bodily organ and it’s called an iPhone or a smartphone. It can have amazing functionality. It epitomizes consumers’/people’s need for convenience, simplicity, immediacy, autonomy, and technology that works for them.

The Current and Future State of Health Analytics

To exploit opportunities for market differentiation and to avoid Kodak moments, analytics needs to meet the challenge. And although there has been great progress in analytics in healthcare, it is far behind other industries in supporting business objectives. What’s holding it back the most is the digitization of the industry. Other industries, such as retail and banking, have perfected the digitization of their business transactions and reap the benefits from analytics. It is definitely true that healthcare has much more complex and varied types of transactions, for example, billing, clinical, and plan enrollment. Additionally, the industry is very fragmented. If the different segments of the system do not communicate well, it makes for a nearly impossible task to build an analytic infrastructure with them or around them to foster communication and integration.

Just as in Maslow’s hierarchy for self-actualization, a business must mature through a series of stages before it can reach its full potential through analytics. At its base, the “physiologic” needs (like food and water) need to be secured first. In healthcare analytics, this involves having the core administrative systems working properly such that basic reporting requirements can be met, including the ramp up for many compliance demands resulting from the ACA. Often, and with the increased regulatory demands and competitive threats placed on healthcare providers and payers, this involves a review of legacy systems and a total rethinking of IT capability and functionality. And this can be very expensive and take years to complete. So, for most organizations, there is a commingling of the old with the emerging new information capability, but during the process there might be scant results that demonstrate the worth of analytics to improve the business.

The real worth of analytics comes into play when the organization has a well-functioning integrated information management system. For many of the industry challenges, this requires an integrated view of the patient-member-person in order to address behavior change for prevention and treatment and to maximize marketing offerings that are tailored to the individual customer.

Ultimately, the self-actualized, analytics-optimized organization will be able to use its real-time, integrated, comprehensive information to address new market opportunities and indeed to master continual transformations of the organization.

However, this need not be a linear progression and the perfect should not be the enemy of the good. Value needs to be extracted from health analytics all the time. It needs to show a clear contribution to earnings. It cannot wait for the perfect system to be erected because during the building process new demands will change what perfection looks like. And if the analytics is not clearly contributing to the bottom line, it will be considered a cost center and will be subject to budget reductions when times get tough for the business.

Top-Ten List of Healthcare Analytics Challenges

Figure 2.3 lists the most important analytics challenges, and the sections that follow discuss each challenge.

Connecting the “Pipes” and Integrating the Data

This is the most critical challenge to the full expression of analytics in healthcare. In provider settings, it starts with the electronic health record. Digitizing the medical record has been discussed for decades and proceeded in fits and starts until 2009, when progress accelerated because of the federal Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act, which was to advance the use of health information technology. HITECH, through Medicare and Medicaid, provides incentives to physicians and hospitals that adopt and demonstrate “meaningful use” (MU) of EHR systems. According to a 2012 National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Data Brief,37 more than 50% of all physicians had adopted an EHR system by the end of 2011 and, of the remaining 50%, half plan to purchase or use one already purchased within the next year. Similarly, a 2012 survey of U.S. hospitals indicated that EHR adoption increased from 16% in 2009 to 35% in 2011.38

This is great progress, but there is a long way to go. These systems facilitate communication among doctors and caregivers and various departments within hospitals and associated outpatient physician practices for the delivery of clinical care. However, connecting to providers outside the hospital walls or to other healthcare systems and then to other health systems in the community is a challenge because of “dueling” systems. That’s the purpose of the health information exchange (HIE), to mobilize healthcare information across organizations. But for now, if a patient goes from one hospital system to another, the mode of medical record transport is usually the patient carrying the record, X-rays, and lab findings. And understanding whether the patient received services from other health providers, such as public health agencies or schools that provide vaccinations and tests, is infrequently captured in the medical record.

Analytics staff within hospitals are largely concentrating on implementing the EMR and getting people communicating better and improving care in the process. But after the data collected in these systems is used for that specific clinical purpose, most of it becomes “digital waste” and is not reused for other analytic purposes. It is stored away, like the cryopreservation (freezing) of dead human beings awaiting the technology to bring them back to life. The difficulty in using the EMR data is that most of it is unstructured. There are ways to unlock unstructured data and to transform it into standardized data that can be reliably retrieved and combined with like data from other systems. However, this is still a work in progress and best-practice illustrations of successful implementations are not at all abundant.

Integrating data from across the enterprise and beyond is also a major construction undertaking. This involves the building of sophisticated data warehouses that bring together a wide scope of information including clinical, financial, administrative, and more. A good example of this is from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC). It recently announced a five-year, $100 million investment in enterprise analytics, in partnership with a variety of technology partners including Oracle, IBM, Informatics, and dbMotion. It hopes to address big clinical and genomic prediction questions such as “What if a doctor could easily predict which treatment would be most effective and least toxic for an individual breast cancer patient, based on her genetic and clinical information?”39

There is great hope and promise to get clinical processes and the healthcare system “wired.” Organizations like UPMC are willing to make very significant investments over a long-term horizon to achieve potentially transforming goals. When these early innovators achieve success, others will follow. Whether the “pipes” goal is to digitize the medical records of a hospital or health system, or to integrate diverse data into data warehouses, what is clear is that the digital construction process is where the majority of analytics time is spent. The challenge will be that while huge investments are made in improving IT systems, the business is not deriving much value from it today to improve business results.

Supporting Healthcare Reform

After 50 years of debating what healthcare reform should be, it’s finally done (mostly). The policy analyses and politics are mostly over and now the hard work of implementation is underway. Analytics will be central to at least three key areas of the legislation, including insurance reform (especially health insurance exchanges), CMS innovations (especially ACOs and the consumer operated and oriented plans [CO-Ops]), and health information technology (HIT) (especially meaningful use).

The health insurance exchanges will open up the “insurance malls” in October 2013. Although most states, including almost all of those with a republican governor, have decided not to form their own exchanges and will probably defer to the federal government to organize and run it, others are well on their way to being up and running on schedule. The exchanges themselves are a huge HIT project involving the assessment of eligibility, enrolling individuals into coverage, and the collection of insurance premiums. Additionally, the exchanges will bring together quality, cost, and benefit information and present it to applicants to facilitate their choice of plans.

The larger analytic challenge is with the health plans as they move to a direct-to-customer business model. This will require a great deal more knowledge about their new customers in order to facilitate member acquisition and member behavior change to improve outcomes and reduce costs (now that they cannot make profits solely on skimming the healthiest people). This will involve a greater understanding of marketing analytics, including lots more data about individuals’ characteristics and risks and about how they have used the various components of the healthcare system and the insurance system. This will require a 360-degree view of their customers and the underlying analytics and IT infrastructure to support it.

Some payers are also changing the nature of their business. They are supporting ACOs by becoming data aggregators to help them assess risk, utilization, outcomes, and shared savings through a better understanding of claims, member, and other data.

An unintended, positive outcome from reform is the coordination and communication among analytics staff within organizations. These staff from finance, quality improvement, insurance, and various business units have a new organizational imperative. And because lots of money is at stake, whether it be for meaningful use, readmissions, or patient satisfaction, a “burning platform” to address the money concerns has driven people together like nothing else before.

Improving Clinical Practice through Decision Support

Connecting the pipes and integrating the data are critical, foundational, developmental stages for analytics. Making use of the data and turning it into useful, accessible, timely, and user-focused information for decision making is where the payoff happens.

Improving clinical decisions encompasses a number of initiatives:

• Shaping care through decision rules. These include rules for care protocols, drug interactions, diagnosis, and order sets that can be included in EMRs.

• Monitoring and optimizing performance through balanced scorecards and dashboards that are used for management review and interventions.

• Supporting physicians and caregivers with tools for clinical decision making at the point of care.

Analytics supports the latter two initiatives the most, as described in the following sections.

Dashboard

Dashboard reporting is common in healthcare. Balanced scorecards provide a critical lens on the performance of the key success factors of various domains that encompass a complete picture of the business. For hospitals, the domains usually include quality of care, patient safety, patient experience, access, and financial outcomes. Many indicators are rolled up into a summary, composite measure for each domain. Targets are set for each indicator and domain composite. The dashboard tracks progress relative to target, usually on a monthly or quarterly basis. Visualization of progress toward goals includes the use of traffic stoplight signals of green, yellow, or red to indicate, at a glance, whether management needs to intervene. The component indicators of each domain can be accessed with a click on the domain composite. The reporting is meant to be simple and direct and home in on areas in need of attention.

It is important to note that these are management reports and are largely “top down” intervention tools. For example, if performance targets on a given domain are not achieved, managers are held accountable and need to explain the causes and how remedies will be applied. It is also important to note that these reports are at an organizational level and seldom go down to the physician level, although the data should be available at that level for physician-related indicators such as quality and patient safety.

There are a few rationales as to why dashboards do not go to the granular level of the physician. Most notably, practicing physicians might not view this aggregate information on their patients as valuable to them in the treatment of individual patients. Also, publicly reported performance information on individual physicians (or teachers, for that matter) incurs the wrath of those who are evaluated because they feel that the metrics are not scientific, risk adjusted, or fair.

In the Chapter 6, “Sports,” it will be clear that healthcare can learn a lot from sports, believe it or not. Lessons can be learned about measuring individual performance and why a concentration on the individual rather than the team can be counterproductive for both industries.

Supporting Physicians

Physicians need just-in-time information to support them in the diagnosis and treatment of individual patients. Real change in healthcare takes place “on the ground” at the physician/patient level. But the context of the clinical encounter is demanding on a number of fronts. One is that the practice of medicine is very fast-paced because of the efficiency demands placed on physicians with appointments that last less than 10 minutes. Hence, analytics needs to demonstrate its value to provide information, just in (real) time, and customized to the needs of the user.

However, physicians do not use information optimally for a variety of reasons. The first reason is that it is impossible to keep track of all the emerging research and related insights about diseases and new treatments. Doctors just do not have enough time to digest this information in their scant leisure time. The second is that it is not always possible for doctors to get the information they need on a given patient because they might not be able to find it if the records have not been digitized or integrated. The third reason is that even if this information is available, it might not be used because physicians are trained in and have a strong preference for intuitive thinking. They do not have the inclination to sort through lots of information and decision maps to make data-driven decisions. One indicator of the need for more data-driven decision making in medicine is that diagnostic errors occur about 20% of the time.40

One emerging solution that might transform the practice of medicine is machine learning. IBM demonstrated a compelling use of machine learning (and natural language processing and predictive analytics) with its Watson technology by beating two grand champions on the Jeopardy! TV quiz show. IBM is now moving beyond quiz shows and working on healthcare solutions, mostly in the area of differential diagnosis. One of the institutions it has partnered with is Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.41 The goal according to Sloan-Kettering is to have the technology gather and assimilate information from the research literature and from the Center’s vast clinical experience documented in its medical records and other files to “bring up-to-date knowledge to the bedside of every cancer patient.”42 Watson might be able to do this through its capabilities to read and understand language, interact with humans, remember everything, and provide answers to real-time questions. How the information will be delivered to the physician, how it might transform the practice of medicine, and whether physicians will embrace the technology are all very important, open questions. It is certainly a very bright star illuminating and guiding the emerging field of machine-enabled clinical decision support.

Other industries do not have a lot to teach healthcare in this area. There is certainly a lot of theory and research about machine language and its related technologies, but no clear evidence of its utility to improve business results. Healthcare is forging the way and other industries might be able to learn from it.

Improving Population Health

Population health is more a slogan than a business strategy at this point and might wallow in the background until a few things happen. Payment policy needs to change from fee-for-service to global payments; outcomes need to be measured and adequately rewarded financially; ACOs and medical homes need to move beyond a focus on coordinated care for sickness and embrace prevention just as thoroughly. As discussed earlier, many of the shortfalls and the opportunities for improvement for the health system stem from less than full attention to population health issues. This is perhaps the biggest area where healthcare can learn from other industries and is addressed in almost every industry comparison. It might seem counterintuitive that other industries take a “population” perspective. Banking, retail, and political campaigns market and attempt to sell and serve everyone who could possibly be a customer, unlike healthcare, which concentrates on the sick when they seek care and leaves the majority of members and patients relatively unnoticed. This is the group that needs to be focused on for prevention and early intervention of diseases.

Addressing the Big Promise of Big Data

There have been big claims about the potential for “big data” in healthcare. McKinsey states that “if U.S. healthcare were to use big data creatively and effectively to drive efficiency and quality, the sector could create more than $300 billion in value every year.”43 And technology vendors such as SAP state that “with the right information at the right time, anything is possible...and with real-time, predictive analysis comes a shift toward an increasingly proactive model for managing global healthcare.”44 Big data is sometimes subsumed under personalized medicine with a strong emphasis on the integration of genomic and phenotypic data. The result of such an integration could lead to answers to important questions, such as whether a certain chromosomal variation is related to a disease, which could then fuel predictive and preventive medicine in the future. Moreover, boundless data in the form of personal and public and integrated medical data, in combination with the right channel—especially mobile—enable much better identification of high-risk patients, more effective interventions mapped to their specific needs, and closer monitoring.

Big data is also big business. In addition to the traditional technology players such as IBM, Oracle, SAS, and many others, more than 200 new businesses are developing healthcare solutions.45 The focus of these innovative companies is less on data management or traditional retrospective reporting and more on predictive modeling, direct intervention for behavior change, and using mobile apps that track location, daily activity, and patient-reported events.

Healthcare lags other industries, including banking and retail, in its use of big data because of the challenges with complex and unstructured data, the reluctance to use external data, data integration issues, and serious concerns about patient confidentiality. More important, perhaps, is the need to ask the right questions and to formulate the use cases that make sense for the business. Finally, achieving the big potential of big data is a way off. First movers may realize breakthroughs to outpace the competition if they have the stomach for the risk and cost involved. But, there are many ways to chip away at big data, especially by using external data and omnichannel platforms that can address business needs today. A few of these are the direct conclusions of this book.

Optimizing Data Sources

The world is full of relevant data and a lot of it resides outside of healthcare. External data can address very specific questions about healthcare business issues to change people’s behavior, ranging from marketing to early detection of diseases. And it can do it cheaper and better—and do it now—while the big 360-degree integration project is being perfected and the big data neural transformation of the world evolves.

These data come from privately aggregated and publicly available databases on a wide range of personal attributes and can focus on specific interventions to improve health. For example, data on height and weight can be used to calculate a body mass index (BMI) that can indicate the degree of obesity, which is predictive of diabetes onset. Given the enormity of the diabetes problem in the U.S., early identification is very important to save lives and dollars. Yet the basic information on height and weight is not collected on the usual claims forms or member registration forms. Although it can be collected in EHRs, it might not be extractable from them for population health purposes. Additionally, it comes from patients in treatment and overlooks those people who have not yet entered the healthcare system. Healthcare has attempted to gather the data directly from people on health risk assessments (HRAs), but the response rate is too low for the data to be useful. And the people who tend to fill out the HRAs are the very healthy people because documenting good health is often linked to monetary incentives for wellness programs.

Height and weight are at the tip of a very deep iceberg on what is available about individuals in this über-surveillance society. Later chapters document how other industries have teamed with “data snatcher” companies that collect reams of data on people from public records, purchases, Internet activity, polls, and more. Then, the newly mined data are used to literally win the presidential election, predict life changes, and amass patterns indicative of terrorism. Although there are many privacy and ethical concerns about these data, the use of it is rampant and the business successes have been noteworthy.

The healthcare industry has been reluctant to use these resources when compared to other industries such as retail and banking. There are several explanations. Lawyers get squeamish about the collection and integration of any data that has an ID on it. HIPPA might be a barrier. There is a knee-jerk reaction that it might be all right for other (lesser) industries, but not for healthcare. And there is enough unused healthcare industry data to keep IT busy for decades.

A case is made in the industry chapters that healthcare is blinded to the potential usefulness of external data to its detriment. There are many business purposes ranging from customer analytics for marketing, to predictive analytics to identify people at risk, to behavior change analytics to improve engagement in one’s own health improvement.

The technology is available to collect, integrate, and make all sorts of computations on the data. One problem is whether there is a compelling ROI in doing it all. This revolves around the important issue of what the business purpose is and whether the business can execute on the data. For example, the data on BMI can be obtained at a cost of about $20 per 1,000 matches to a health plan’s membership list. This would seem to be a modest cost even if the legal fees to get it were to add an additional overhead cost of $5 per match! Integrating the data is not difficult and stratifying people by obesity is relatively straightforward. This seems like a worthwhile investment so far.

According to the American Diabetes Association, there are 79 million people in the U.S. with pre-diabetes and 7 million with undiagnosed diabetes. The medical expenditure for people with diagnosed diabetes is 2.3 times that of people without diabetes.46 So the potential cost savings from early intervention to thwart diabetes is mammoth. And the analytics investment is low.

The concern is whether the health plan has the behavioral change technology to actually achieve change that would result in obesity reduction. The first step, and it is an important, fundamental contribution of analytics, is to identify. But a whole series of implementation linkages needs to unfold for the analytics investment to pay off. And this requires that the business is coordinated, integrated, and impactful.

Reaching for Predictions

Predictive modeling has been around a long time. The advances that have occurred to make this a powerful tool are not so much the statistics or theoretical models but the technology advances to collect, capture, integrate, process, and make computations on large amounts of data. Virtually every valuable analytic solution in healthcare and in other industries involves predictive modeling. Describing what happened yesterday in static, standard reports is so, er, yesterday. The breakthrough with analytics comes with predicting what will happen tomorrow.

Other industries described in this book include many examples of how modeling on large, multifaceted databases produces important business results. Retail, credit, banking, and presidential campaigns can predict individual behavior before the individual is aware of it. For example, credit companies have determined the major risk factors related to default, and one of the most predictive is divorce. They have created divorce algorithms based on individual purchasing records that indicate high risk of divorce. Retail can predict what you will buy before you know it. And on and on.

Healthcare has a great need to predict risk and outcomes for specific segments of patients/people/members. These potential predictive modeling sweet spots from other industries and the potential adaptability for healthcare are a major theme of the book.

Appreciating the Customer

People are called many names in healthcare, including patient, consumer, member, citizen, and client...but hardly ever customer. This blind spot in healthcare to recognizing the value of the individual as the customer is both understandable and delimiting.

Previously, we noted that customers are defined as the ones who pay the bills, and the individual is a minor player in that regard, superseded by employers, insurance companies, and provider groups. So thinking of the patient/member as a customer can be a counterintuitive. And the term “customer” might have a negative connotation to some in healthcare. A customer might be regarded as someone you have to “deal with” who needs to be “converted” for the sale. And the track record of some business functions such as marketing and customer service demonstrates that what is done to customers can be annoying and intrusive or downright antagonizing and profiteering.

The appreciation of customer value must go beyond “the sale.” It needs to be about a relationship over time. In the absence of a relationship and some element of loyalty, the customer can shift companies at the click of a mouse to get the lowest price or the flashiest coupon offer. Mahatma Gandhi thinks of customers in a respectful way:

A Customer is the most important Visitor on our premises.

He is not dependent on us, We are dependent on him.

He is not an interruption of our work, He is the purpose of it.

He is not an outsider to our business, He is a part of it.

We are not doing him a favor by serving him, He is doing us a favor by giving us an opportunity to do so.

Healthcare needs to be more patient-centric and more customer-centric to achieve the important goal of helping the individual change behavior. The absence of appreciable “people engagement” in healthcare has long been lamented, but progress in areas such as patient-centricity, shared decision making, prevention, medication compliance, and having more “skin in the game” has been slow and exerts a significant drag on outcomes and costs.

There are indications that this is changing for the better in healthcare. The ACA has two important provisions that will require a focus on the customer. These include the health insurance exchanges, which will require a retail relationship with individuals. Additionally, CMS value-based performance payments to hospitals reward hospitals with good patient experience ratings based on patient ratings on their hospital stay. Also, the patient engagement movement has worked hard to change the behavior of healthcare providers to include more involvement of patients and families to improve health outcomes.

Jessie Gruman, president of the Center for Advancing Health, states it eloquently: “If we don’t connect with at least one trusted clinician, show up when we need to, get the tests we agree on, use effectively the drugs and devices you recommend, carefully follow directions after a hospital stay and try our damndest to lose the weight and walk around the block more often, medical interventions are squandered. Our suffering continues. Time and money are wasted: yours and ours.”47

Healthcare can learn lessons about customers from all the other industries in this book. This includes having a full view of the customer through lots of data, using predictive analytics, and implementing mass customization to capture a market of one.

Aligning with the Business

Analytics can do many wondrous things but without the support of the business it can achieve very little. After all, the business units fund analytics. Analytics exists to support the business unit needs. Similarly, technological solutions are relatively easier to develop than are the sociological steps needed to absorb the technology into successful management actions.

Throughout this book the discovery of the best analytics starts with an understanding of the industry’s purposes, challenges, core functions, and unique business sweet spots. The best analytics emerge from this admixture.

In healthcare much of the analytics work is currently done away from the business, and for all intents and purposes it could be in a different country. It has to do with building the pipes mostly within the IT organization. Business agrees with the building of a data warehouse and says, “Let us know when it is done.” But when the inevitable implementation snags occur and IT asks for more funds to complete the project, the business can and does balk. The business demands value generation every day and this has to include analytics as well.

When analytics works hand in glove with the business, amazing things can happen. The analytics function grows to its full potential and the business succeeds in ways that were impossible without the partnership with analytics.

Inducing Social Exchange

Mobile technologies are creating a social revolution. These technologies allow the full expression of the person’s long-held desire for convenience, simplicity, immediacy, autonomy, and technology that actually works for them on a 24/7 basis, and is a pleasure to use. Mobile is the communications nexus for people. We are continuously affixed to the world through it. And most important, we control the flow of the information.