Chapter 7

Admissibility of Digital Evidence

Learning Outcomes

After reading this chapter, you will be able to understand the following:

The structure of the legal system in the United States;

The role of constitutional law in computer forensics;

Principles of search and seizure of computers and other digital devices;

Rules for the admissibility of evidence at trial;

Case law concerning the use of digital surveillance devices by law enforcement;

Cases of computer forensics gone wrong;

Structure of the legal system in the European Union; and

Data privacy and computer forensics in the European Union.

The United States legal system is one of the most complicated in the world, primarily as a result of a dual legal system that is comprised of federal and state laws and their respective court systems. This complexity also makes for arguably one of the most exciting legal systems in the world.

Like other legal systems worldwide, U.S. legislation has been complicated further by the growing importance of digital evidence in criminal investigations and trial proceedings. U.S. legislation at all levels (federal, state, and local) has been impacted by computers and other digital devices. This chapter details how traditional laws have been applied to new technologies and how traditional laws have been amended to address the admissibility of digital evidence, and how new laws have been introduced to keep up with advances in technology.

History and Structure of the United States Legal System

First and foremost, a state-based legal system predates the federal legal system in the United States. Prior to the War of Independence, each of the 13 states operated with autonomy, with their own legal system, including their own official religion. For example, Maryland was originally established as a Catholic colony, whereas the Church of England was the state religion for New York, Virginia, Georgia, North Carolina, and South Carolina. These disparate entities, formerly known as colonies, were eventually united by a common outrage: taxation by Britain without representation. Although there was some notion of a confederation, this union did not have a tremendous amount of meaning until it became apparent that states needed to be united to fight the “oppression” of taxation by the British Crown and government. Furthermore, this confederation could be effective only if states were forced to fund a Congress that could then fund a Union Army. These states would also require this Congress to establish common laws for this federation—in other words, the institution and ratification of federal laws. Understandably, it took quite some time for each of these states, with a variety of denominations, ethnicities, and values, to come to an agreement on a new legal system that would coexist with their established state system. The relationship between a federal and state system was contentious during colonial times, and this relationship was severely tested during the American Civil War, which was not as much about the abolition of slavery as it was about the supremacy of the federal government on contentious issues such as the extension of slavery. The Civil War was also about the future of the U.S. economy: the rural, agrarian economy of the South, which was a vision of the future for founding father Benjamin Franklin, versus the urban capitalist society of the North, which was the way forward for Alexander Hamilton.

What does all of this have to do with computer forensics? The answer is that both federal and state laws impact criminal investigations and court trials. Moreover, investigations and court proceedings at the state and county levels are influenced by the Constitution, which is a federal document that protects the rights of the individual. Additionally, a computer forensics investigator must abide by federal and state laws, when conducting an investigation.

Interestingly, a case can be tried in a number of different ways. For example, in a criminal investigation, a jury might find the defendant not guilty. A jury is a group of people put under oath to hear arguments at trial and render a verdict of guilty or not guilty. But a civil lawsuit then can ensue, with a victim seeking monetary compensation against an offender or third party for physical damage or emotional distress. The plaintiff is the person who initiates the lawsuit and is responsible for the cost of litigation. The defendant is the person who defends him- or herself in a lawsuit. O. J. Simpson was acquitted of the murders of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goldman in a criminal trial, but the families successfully secured a $33.5 million settlement against him in civil court.

The Civil War ended more than a century and a half ago, but there is still a dichotomy of laws and authority between federal and state institutions in the United States. Problems still exist today, as evidenced by certain states with different immigration laws compared to the President of the United States, and other members of Congress. This tension is also clearly illustrated by California’s state law legalizing the use of marijuana for medicinal purposes, yet these distributors are operating illegally under federal law.

The United States Constitution was created on September 17, 1787, and then subsequently ratified by each state. With this ratification, the Constitution (and federal government) is supreme concerning the powers delegated to it, yet it still recognizes the sovereignty of the states and their supremacy over matters of state. The Constitution is a framework that defines the relationship between the federal government, its united states, and its citizens. The Constitution has been amended 27 times. The Bill of Rights refers to the first 10 amendments to the Constitution, which protects the rights of the individual.

The first three Articles of the Constitution establish the three branches of government: Article I, the Legislature (Congress), which is comprised of the House of Representatives and the Senate; Article II, the Executive (President); and Article III, the Judicial (Supreme Court and lower federal courts). In summary, Congress writes laws, the Supreme Court interprets those laws, and the President has the power to either sign into law or veto Congressional legislation.

Origins of the U.S. Legal System

The origins of the legal system in the United States are found in common law and English law. Common law is based on case law and precedent, with laws derived from court decisions. With precedent, court decisions are binding on future decisions in a particular jurisdiction. Therefore, these laws are derived not from legislation, but based on court decisions. The exception to this legal system is Louisiana, where the legal system was originally based on the Napoleonic Code. The Napoleonic Code has its origins in Roman law. Napoleon developed a written, uniform code of laws to assist in the administration of his vast empire.

The Napoleonic Code was based on civil law. Civil law is based on scholarly research, which, in turn, becomes a legal code, and is subsequently enacted by a legislature. There is no precedent. The Louisiana Civil Code Digest of 1808 has changed over time, and the current legal system in Louisiana is not that much different today from other states.

Three primary bodies of law exist in the United States: (a) constitutional law, (b) statutory law, and (c) regulatory law. Constitutional law outlines the relationships among the Legislative, Judiciary, and Executive branches, while protecting the rights of its citizens. It is also referred to as federal law. Statutory law is written law set forth by a legislature at the national, state, or local level. There are codified and uncodified laws in statutory law. Codified laws are statutes that are organized by subject matter. An example of this is the United States Code (U.S.C.). Regulatory law governs the activities of government administrative agencies. This body of law involves tribunals, commissions, and boards that are responsible for decision making. These decisions affect the environment, taxation, international trade, immigration, and so forth.

Overview of the U.S. Court System

It is important to explain the structure of the U.S. court system because you will then have a better understanding of the rationale for cases being tried in federal court versus those cases tried in state or county courts. A criminal prosecution might be tried in federal court because of the jurisdiction, meaning that crimes were committed across multiple states. Another reason for trying a case in federal court might be the nature of the crime. For example, the victim and perpetrator could both be located in California, but the defendant was accused of corporate espionage, which threatens national security and is therefore a federal case. Sometimes a case begins in a state court, but the case is then referred to a federal district court. This is common when the judge has determined that guilt or innocence depends on an interpretation of the Constitution; in other words, it is a constitutional matter.

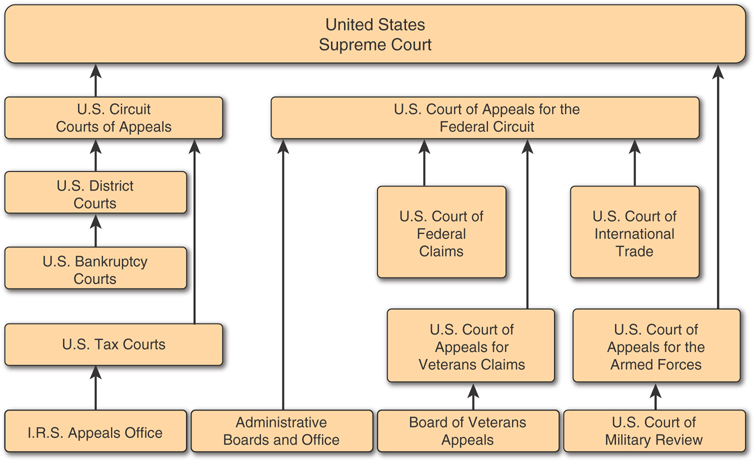

In some cases, local law enforcement in multiple states collaborate. The criterion for determining where the case should be tried is often determined by deciding which of the states has tougher laws for a particular crime. Other times, one state might lack legislation for certain offenses. Figure 7.1 illustrates the basic structure of the court system.

Figure 7.1 U.S. court system

The basic structure of federal, state, and local courts is the same. A defendant has the right to a fair trial, with the outcome determined by a jury of his or her peers. The role of the judge is to facilitate the trial process and ensure that the proceedings are in accordance with the law. The judge must also ensure that the proceedings are free of prejudice and that the innocence of the defendant is presumed until proven otherwise. The burden of proof is always on the prosecution. The role of the jury is to determine the facts of a case and render a verdict.

Appeals Courts

The U.S. court system enables its citizens to appeal a conviction. An appeals court decides whether to hear an appeal. Note that a court appeal is not a trial—there is no jury, so a panel of judges renders a decision about whether a mistake occurred in a lower court. One example might be that evidence was presented at trial that should have been deemed inadmissible. In that situation, the case is sent back to be retried, without the evidence deemed admissible. The prosecution may decide that the case is not worth retrying without a key piece of evidence deemed inadmissible or they may decide to retry the case in court. The panel of appeal judges consists of an odd number of judges and decides whether there has been a mistake of law in a previous trial.

Federal Courts

Two types of federal courts exist. The first type is derived from Article III of the Constitution. It consists of the U.S. District Courts, the U.S. Circuit Courts of Appeal, and the U.S. Supreme Court. There are two other types of Article III courts: the U.S. Court of Claims and the U.S. Court of International Trade. These special courts do not have general jurisdiction. Jurisdiction refers to the scope of legal authority granted to an entity.

The next category of federal court was not established by Article III but rather was created by Congress. These courts include magistrate courts, bankruptcy courts, the U.S. Court of Military Appeals, the U.S. Tax Court, and the U.S. Court of Veterans’ Appeals.

Supreme Court

Under Article III, the President of the United States is responsible for appointing federal judges, which includes Supreme Court justices. Their appointment is subject to the approval of the Senate. The appointment is for life unless removed through impeachment. The Supreme Court has one chief justice and eight associate justices. The role of the Supreme Court was largely decided with the case of Marbury v. Madison, in 1803, when the court demonstrated its right to interpret the Constitution and be the ultimate decision-maker in congressional issues. In other words, the judiciary branch is the ultimate arbiter of the law, not Congress or the President.

Article II of the Constitution outlines the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court and other federal courts:

The judicial Power shall extend to all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made, or which shall be made, under their Authority; to all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls; to all Cases of admiralty and maritime Jurisdiction; to Controversies to which the United States shall be a Party; to Controversies between two or more States; between a State and Citizens of another State; between Citizens of different States; between Citizens of the same State claiming Lands under Grants of different States, and between a State, or the Citizens thereof, and foreign States, Citizens or Subjects.

Federal Appellate Courts

There are 13 circuit courts of appeals, which were first established in the original 13 states of the United States. Today there are 12 regional circuit courts in several cities, as well as an additional Federal Circuit Court (13th Court) in Washington, D.C. Each of these circuits is assigned a circuit justice from the Supreme Court.

This chapter highlights many notable circuit court decisions with respect to the admissibility of digital evidence. One of the most noteworthy districts is the Ninth Circuit, which is by far the largest circuit and covers districts in Alaska, Arizona, California (Central, Eastern, Northern, Southern), Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington (Eastern and Western), with appellate jurisdiction over the territories of Guam and Northern Mariana Islands courts. These courts hear cases referred from lower federal district courts, known as U.S. District Courts.

Ultimately, the federal appellate courts can refer cases to the U.S. Supreme Court. Typically, three judges sit in these courts.

U.S. District Courts

There are 94 U.S. District Courts across the United States. Every state has at least one District Court, and larger states have more. For example, New York has a Southern District of New York (Bronx, Dutchess, New York, Orange, Putnam, Rockland, Sullivan, and Westchester counties), a Northern District of New York (from Ulster County and North), the Eastern District of New York (Kings, Nassau, Queens, Richmond, and Suffolk counties), and a Western District of New York. There can be multiple courthouses in each district. For example, in the Southern District of New York, there are courthouses in White Plains and New York City (Manhattan).

Most federal cases begin in a U.S. District Court. Cases in these courts can be civil or criminal. A kidnapping or intellectual property dispute case generally is the type of case tried in a U.S. District Court.

State Courts

The state court system varies from state to state. Nevertheless, there are some similarities. Local trial courts are located throughout the state and hear cases at the lower level. If the defendant is found guilty, the defendant can appeal a conviction in a state appellate court.

State Appellate Courts

Two types of state appellate courts exist. Often referred to as supreme courts or courts of appeal, these are the highest courts in the state judicial system. They have discretion over which cases they hear and are often referred cases where there could be an error in determining the law. They are confined to a particular jurisdiction and can be asked to preside over contentious decisions, like elections. Anywhere from three to nine judges can sit on a panel in a state appellate court.

Intermediate Appellate Courts

Intermediate appellate courts exist in 40 of the 50 states. The following states have no appellate courts: Delaware, Maine, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Vermont, West Virginia, and Wyoming. The number of these courts varies from state to state, as does the number of judges. Decisions from appellate courts can be appealed to the state’s highest court, which is referred to as the State Appellate Court.

Trial Courts of Limited Jurisdiction

Trial courts of limited jurisdiction are limited to hearing certain types of cases. These courts include the following:

Probate court: Sometimes referred to as a surrogate court, this court hears cases relating to the distribution of a deceased’s assets.

Family court: This court hears cases relating to family matters, including child custody, visitation, and support cases, as well as restraining orders.

Traffic court: This court hears cases relating to driving violations. An individual who is cited for a traffic violation can pay the fine (plead guilty) or can appeal in traffic court. With DUI (driving under the influence) citations, the individual may be required to appear in court before a judge. DUI and DWI (driving while intoxicated) are crimes, and these cases can be tried in criminal courts in many jurisdictions.

Juvenile court: In this court, minors are tried by a tribunal. The court generally hears cases against defendants who are under the age of 18. However, more serious crimes, like murder or rape crimes, that are committed by juveniles can be moved to a different court, where the defendant is prosecuted as an adult.

Small claims court: The function of these courts is to settle private disputes involving relatively small monetary amounts.

Municipal court: This court hears cases when a crime has occurred within their jurisdiction. These can include DUI, disorderly conduct, vandalism, trespassing, building code violations, and similar offenses.

Trial Courts of General Jurisdiction

A trial court of general jurisdiction can basically hear any kind of criminal or civil case that is not exclusive to another court.

New York Trial Courts

It is probably helpful to see an example of how the court system is set up in a particular state. For this example, let us consider New York State. In New York City, a trial by jury can be held in the following courts:

Supreme Court

New York City civil court

New York City criminal court

Outside of New York City, a jury trial can be held in the following courts:

Supreme Court

County court

District court

City court

Town and village court

A civil trial lasts for an average of 3 to 5 days; a criminal trial generally averages 5 to 10 days. The following people generally are present at trial:

Attorneys (or Counsel)

Court reporter

County clerk

Court officer

Defendant

Interpreter

Jury

Plaintiff

Prosecutor

Spectators

Witnesses

In the Courtroom

It is helpful for a computer forensics examiner to understand the pretrial and trial process because they might one day become part of that trial as an expert witness. The following is an outline of the steps taken during the pretrial and trial in a civil or criminal case:

Jury selection

Oath and preliminary instructions

Opening statement(s)

Testimony of witnesses and presentation of other evidence

Closing arguments

Jury instructions

Deliberations

Verdict

Sentencing

The Jury

The right to a trial by jury is clearly outlined in the Sixth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution:

In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defense.

Voir dire is the questioning process used in the jury selection process. During voir dire, lawyers and, in some cases, the judge ask potential jurors questions to determine any prior knowledge of the facts of the case or any biases that could influence their impartiality in the case. All defendants are presumed innocent until proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. Jurors may be required to fill out a survey prior to oral questioning. In a criminal case, voir dire is recorded by the court reporter and becomes part of the trial record. If used, the questionnaire and responses also become a part of the trial record. Generally, in civil trials, voir dire and any questionnaire would not become part of the court record.

Civil trials typically have 6 jurors and up to 4 alternates. For criminal felony trials, there are 12 jurors and up to 6 alternatives. In lesser criminal trials there may be 6 jurors and up to 4 alternates. During the trial, jury members may not discuss the trial amongst themselves or with others and may not read about the case. This is because each juror must hear all facts of the case before making a decision. A juror can be held in contempt of court if he or she discusses the trial before deliberations occur. In certain trials, particularly highly publicized trials, the jury can be sequestered in local accommodations, instead of being allowed to go home each day. Jury sequestration refers to isolating the jury and preventing external influences on jury decisions. Contempt of court means violating the rules of court procedure. The foreperson is usually the first juror seated and is ultimately responsible for reporting the verdict to the judge.

Opening Statements

During a criminal trial, the prosecution makes an opening statement first because the burden of proof is on the prosecution. The burden of proof implies that a defendant is innocent until proven guilty, the prosecution must prove guilt, and the defense must not prove anything. Under the Fifth Amendment, the defendant need not speak ever during the trial. Of course, in practice, defense counsel makes opening and closing remarks and is involved in direct examination and in cross-examination. A direct examination is the questioning of counsel’s witness in a trial. A cross-examination is the questioning of the opposing side’s witness in a trial.

Verdicts

Deliberations are the process whereby the jury reviews the evidence from the trial and discusses opinions about the case. A hung jury occurs when the jury cannot come to a unanimous decision in a criminal trial and a retrial must occur. Unlike a criminal trial, in a civil trial, the decision by the jury does not need to be unanimous. The jury also decides compensatory issues in a civil trial.

After the jury has reached a verdict, it is the responsibility of the judge to determine the sentence. Following deliberations, the foreperson informs the court officer that the jury has reached a decision and will deliver a verdict.

Criminal Trial Versus Civil Trial

Criminal charges are initiated by government prosecutors on behalf of the people. As a result, the defendant is indicted to stand trial and answer questions relating to serious crimes or provide information. A felony is a serious crime and generally carries a penalty of a year or more in prison. A misdemeanor is a less serious crime, with a possible sentence of less than a year. In a civil trial, depositions may be taken whereas in a criminal trial, they are generally not taken. A deposition is sworn witness testimony taken, prior to a trial (discovery phase), which can be presented during a civil trial. Thus, witness testimony and cross-examination are largely based on their depositions recorded during discovery. In a criminal trial the government accuses an individual of breaking the law, a statute or a penal law that appears to have been violated. In a civil case, a case is brought by an individual or organization (including corporations and the government), referred to as the plaintiff, against an individual or organization.

Civil trials generally involve disputes over money. If successful, the plaintiff is awarded money by the jury. A civil trial identifies whether an entity failed to act reasonably and prudently under a certain set of circumstances. The standard that needs to be met to win a civil trial is referred to as preponderance of the evidence. This means that most of the evidence presented indicates which party was in the right and which party was in the wrong. In a criminal trial, the burden of proof is on the prosecution to prove that the defendant is guilty. In a civil trial, the burden of proof begins with the plaintiff. However, in civil trials, the burden of proof can move to the defense to prove that he or she was not at fault. In a criminal trial, the standard to prove guilt is “beyond a reasonable doubt”. This means that, regardless of the evidence, there must be no doubt in the minds of all jurors that the defendant is guilty. Of course, this is a different standard than preponderance of the evidence. Table 7.1 summarizes the differences between criminal and civil trials.

Table 7.1 Comparison of Criminal Versus Civil Trials

Description |

Criminal Trial |

Civil Trial |

Deposition |

No |

Yes |

Trial law |

Statutes, penal laws, and precedent |

Plaintiff claims defendant was negligent |

Charges |

Accused of felony or misdemeanor |

Lawsuit |

Voir dire |

Part of trial record |

Not recorded |

Litigant |

Government prosecutor |

Plaintiff (individual or organization) |

Jury members |

Up to 12 jurors + 6 alternates |

6 jurors + 4 alternates |

Verdict |

Must be unanimous |

Majority rule |

Sentence/Penalty |

Delivered by the judge |

Delivered by the jury |

Evidence Admissibility

The judge is responsible for deciding whether the evidence being submitted is legally admissible. Evidence can include witness testimony. The admissibility of digital evidence is problematic because judges were originally trained to be lawyers years earlier. The prosecution and investigators are often called upon to explain to a judge why certain types of digital evidence should be admitted in a case. A judge may know what an email is but may not know what a system log is and whether it is acceptable in court. These system logs could be critical in determining the fate of a defendant. Moreover, a jury is comprised of individuals with various backgrounds and occupations. For example, a juror could include a pastry chef, a shoe salesman, a geography teacher, or a stay-at-home mother. Imagine how difficult it can be for the prosecution to explain system logs, IP addresses, file registries, and so on.

Constitutional Law

George Mason, author of the Virginia Declaration of Rights, became an opponent of the Constitution because he stated, “It has no declaration of rights”. Mason’s views were strongly considered, and ultimately, James Madison drafted a series of amendments to the Constitution. These amendments were based on Mason’s Virginia Declaration of Rights and later became known as the Bill of Rights. The Founding Fathers originally intended for the Supreme Court to decide on the constitutionality of laws passed by Congress. However, in 1803, with the landmark case of Marbury v. Madison, the Supreme Court became recognized as a court for judicial review. As previously noted, cases that require an interpretation of the U.S. Constitution are handled by the federal court system, which includes the U.S. Supreme Court.

First Amendment

Surprisingly, many books and articles that detail the impact of constitutional law simply focus on the Fourth Amendment and fail to recognize the importance of other amendments, like the First Amendment. So many cases today involve digital evidence that relate to an individual’s First Amendment rights. The importance of this amendment is especially pertinent in cyberbullying cases. The First Amendment states the following:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

We know that this amendment was written long before the advent of digital communications. Nevertheless, we rely on the Supreme Court and lower federal courts to interpret what protections a person posting insulting comments about an individual on a blog has, in addition to the rights of the victim. Can any opinion, no matter how disturbing, be posted on a blog? The initial answer is no—you cannot post a message that could incite a disturbance or violence. In March 2011, the Supreme Court ruled that the First Amendment protected the Westboro Baptist Church from suits seeking emotional distress caused by picketing (see Snyder v. Phelps, 562 U.S. 443 (2011)). The church made headlines with its protests at military funerals and its condemnations of homosexuals, Catholics, and Jews. Others waved signs with captions like “THANK GOD FOR DEAD SOLDIERS”, The Supreme Court agreed to review the case following the conflicting decisions of two circuit courts in Ohio. Unfortunately, there is sometimes a difference between moral responsibility and constitutional law.

First Amendment and the Internet

The Internet is relatively new. Therefore, we rely on traditional laws and case law to guide us most of the time. One area of constitutional law that is still being explored and interpreted involves freedom of speech, the role of the school, and school control over student activities on the Internet.

It is important to begin this discussion with a landmark case that predates the Internet as we know it today. The case of Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, 393 U.S. 503 (1969), was a case heard by the Supreme Court over the rights of a student to protect school policy. Two siblings, John and Mary Beth Tinker, decided to protest the Vietnam War by wearing black armbands to school. The Des Moines School District adopted a policy banning students from wearing the armbands and stated that students who did not comply would be suspended and could return only when they agreed to comply. The Tinker siblings chose not to comply by wearing the black armbands and were also joined by Christopher Eckhardt. As expected, the students were summarily suspended. The Tinker parents filed suit in U.S. District Court (under 42 U.S.C. § 1983), claiming that their First Amendment right to freedom of speech had been violated. However, the court agreed with the school’s policy. When the case came to the Eighth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals, a panel of judges was tied in its decision, which meant that the U.S. District Court decision stood. The Tinkers and Eckhardts then appealed to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court ruled that the Tinkers’ and Christopher Eckhardt’s First Amendment rights had been violated and that the First Amendment does apply to public schools. The Court noted, “It can hardly be argued that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate”.

According to the Supreme Court, student expression may not be suppressed unless it will “materially and substantially disrupt the work and discipline of the school”.

In the case of Layshock et al v. Hermitage School District et al, Justin Layshock’s parents argued that their son’s school violated Justin’s First Amendment right to freedom of speech. Justin created a fake MySpace profile of Eric Trosch, the school principal for Hickory High School, Pennsylvania. Justin posted the following comments online:

In the past month have you smoked? Big Blunt

Use of alcohol? Big keg behind my desk

Your birthday? Too drunk to remember

Big steroid fan

Big whore

Big hard ass

The school asserted that Justin had been disrespectful and disruptive with his comments. Word spread around the school about the profile page. Justin attempted to delete the profile page, and he apologized to the principal. Subsequently, the school contacted MySpace to have the page removed. Justin and his father were summoned to the local police station for questioning, but no charges were filed. Justin, a 17-year-old with a 3.3 GPA, seemed destined for college. However, the school placed Justin in an alternative program comprised of students with behavior and attendance problems. The class met only three hours a day and had no assignments from regular classes. Justin was also banned from extracurricular activities, including Advanced Placement (AP) classes and the graduation ceremony.

Justin’s parents filed suit in federal court, arguing that the school had overstepped its bounds with an off-campus ban. Furthermore, they argued that they were responsible for Justin outside of school. They argued that their son had created a non-threatening parody of the school’s principal. The school argued that Justin’s behavior was disruptive because the school’s computers had to be shut down after so many students visited the profile page, which then led to class cancellations. The IT staff also needed to install extra firewall protection. The court encouraged the school and the parents to reach a settlement, which they did. Justin could return to regular classes, was allowed to participate in extracurricular activities, and could attend graduation.

In February 2010, a three-judge panel of the Third Circuit of Appeal ruled that the school had violated Justin’s First Amendment rights. In its opinion:

…the reach of school authorities is not without limits.…It would be an unseemly and dangerous precedent to allow the state in the guise of school authorities to reach into a child’s home and control his/her actions there…we therefore conclude that the district court correctly ruled that the District’s response to Justin’s expressive conduct violated the First Amendment guarantee of free expression.

The school’s principal later filed a suit claiming that Justin’s actions had damaged his reputation, caused humiliation, and impaired his earnings capacity. The court ruled that Justin’s statements were not malicious, and the principal was ordered to pay punitive damages.

Federal court judges have not always found in favor of a student’s right to post derogatory comments online and not suffer repercussions. The case of Avery Doninger v. Lewis Mills High School is an interesting case related to the First Amendment rights of students in school (see Doninger v. Niehoff, 527 F.3d 41 (2d Cir. 2008)). Avery Doninger was a 16-year-old junior, who was class secretary and a member of the student council at Lewis Mills High School, Connecticut. In 2007, she had been planning “Jamfest” (Battle of the Bands). The event had been canceled three times and was likely to be canceled again because the school’s technician was unavailable. An upset Avery sent emails to get community support and encouraged people to antagonize the principal and superintendent. Avery posted the following message to her LiveJournal blog: “jamfest is canceled due to the douchebags in central office—here is a letter to get an idea of what to write if you want to write something or call her [school superintendent] to piss her off more”. When the school found out about Avery’s online comments, it prevented her from running for senior class secretary. Students wore T-shirts with “Team Avery” on them, which the school banned. Even though Avery’s name was not on the ballot, she still won the student election, although Avery was not permitted by the school to take office. Avery’s mother filed a lawsuit, arguing that it was unconstitutional for the school to prevent her daughter from running for office, and that the school had intentionally inflicted emotional distress. The case was then moved to federal court because it was deemed to be a constitutional matter related to the First Amendment.

The court ruled that, as a student leader, Avery should have exhibited qualities of good citizenship both on and off campus. Furthermore, her comments were intended to irritate the superintendent, which was in violation of school policy. Moreover, Avery had not been barred from school office based on skin color, religion, or politics. Avery had been prevented from running from office because of the language on her blog and the risk of disruption at school. Avery was free to express her opinion, but the First Amendment does not protect the right to run for a voluntary extracurricular position. Her request for a new election was denied. The Second Circuit Court of Appeal ruled that the school did not violate Avery’s constitutional rights in disciplining her because Avery’s blog “created a foreseeable risk of substantial disruption” at the school.

However, there are limits on certain types of speech. In the case of Miller v. California, 413 U.S. 15 (1973), the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed that obscenity is not protected by the First Amendment.

Fourth Amendment

The Fourth Amendment of the Constitution is a part of the Bill of Rights. The purpose of this constitutional amendment was not only to protect individuals against unlawful search and seizure, but also to provide a system of checks and balances in the judicial system. The amendment states the following:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

In the landmark case of Weeks v. United States, 232 U.S. 383 (1914), the Supreme Court stated that a warrantless search of a private residence is a violation of a person’s Fourth Amendment rights. This case was responsible for the introduction of the exclusionary rule. The exclusionary rule states that evidence seized and examined without a warrant or in violation of an individual’s constitutional rights will often be inadmissible as evidence in court in a criminal case. An extension of the exclusionary rule is called fruit of the poisonous tree. Fruit of the poisonous tree is a metaphorical expression to describe evidence that was initially acquired illegally, meaning that all evidence subsequently gathered at every point from that initial search is inadmissible in court.

A number of years later, the U.S. Supreme Court heard the case of Olmstead v. United States, 277 U.S. 438 (1928). Roy Olmstead was found guilty of charges relating to violating the National Prohibition Act. He challenged his conviction based on the premise that his Fourth and Fifth Constitutional Amendment rights had been violated because federal agents had tapped his private telephone calls without a court-issued warrant. The court upheld Olmstead’s conviction. This decision was later overturned by the Supreme Court’s decision in the Katz v. United States case.

It is clear that the Fourth Amendment protects people, not places. The case of Katz v. United States, 389 U.S. 347 (1967), clearly illustrates this assertion. Charles Katz was accused of using a public payphone to conduct his illegal gambling business. Katz later found out that the FBI had placed a wiretap on the payphone. They then used Katz’s recorded conversations as evidence at trial. Katz was found guilty and sentenced. Katz challenged his conviction and argued that his Fourth Amendment right had been violated based on unreasonable search and seizure and because he believed there was an expectation of privacy. Katz was unsuccessful in the Court of Appeals, but the Supreme Court granted certiorari. Certiorari is an order made by a higher court that directs a lower court or tribunal to send it court documents, related to a case, for further review. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of Katz. The Supreme Court opined: “One who occupies [a telephone booth], shuts the door behind him, and pays the toll that permits him to place a call is surely entitled to assume that the words he utters into the mouthpiece will not be broadcast to the world.” Wiretapping constitutes a search and, therefore, requires a warrant. One of the issues that arises with the Fourth Amendment is the expectation of privacy. A link clearly exists between unreasonable search and seizure and the expectation of privacy, but the Supreme Court has not always been clear about the linkage. This causes confusion, and case law is the best guide for litigators.

An expectation of privacy in the workplace is still a grey area. In the case of O’Connor v. Ortega, 480 U.S. 709 (1987), the Supreme Court heard the case of Magno Ortega, a California State Hospital doctor who argued that a search of his office violated his Fourth Amendment rights. Ortega’s supervisors found alleged inculpatory evidence in his office during investigations into employees violating hospital policies. The case was subsequently remanded to the district court, and 11 years later, the Ninth Circuit found in favor of Ortega. With this decision, employer monitoring of employees is reduced when there is a failure to notify employees.

Search Warrants

The Fourth Amendment is arguably the most important part of the Constitution in terms of computer forensics investigations and probably all investigations. Law enforcement must obtain a warrant, issued by a judge or magistrate, before a search or arrest can be carried out. A search warrant is a court order issued by judge or magistrate authorizing law enforcement to search a person or place, as well as seize items or information within the parameters of the warrant. Furthermore, an investigator must demonstrate probable cause. Probable cause refers to the conditions under which law enforcement may obtain a warrant for a search or arrest, when it is evident that a crime has been committed. Law enforcement must show that a crime was committed and that it is more probable than not to expect that evidence exists at the place to be searched.

The case of United States v. Leon, 468 U.S. 897 (1984), created a “good faith” exception to the exclusionary rule. A judge issued a search warrant to the police in Burbank, California. Later, the search warrant was found to be invalid because the police did not properly demonstrate probable cause. Nevertheless, the police were deemed to be acting in good faith when seizing the evidence initially because they believed the warrant to be valid at the time.

In the case of United States v. Warshak, 562 F. Supp. 2d 986 (S.D. Ohio 2008), the Sixth Circuit of the U.S. Court of Appeals held that the government’s seizure of 27,000 private emails from Steven Warshak’s Internet service provider (ISP) violated his Fourth Amendment rights because the emails were acquired without a warrant. The ruling demonstrates that a federal court has recognized an expectation of privacy with emails stored on third-party servers. Nevertheless, the evidence was admissible in court because the government had relied, in good faith, on the Stored Communications Act (SCA).

Email is probably the most important type of digital evidence, and it is continually addressed in many cases. In the case of United States v. Ziegler, William Wayne Ziegler was accused of viewing child pornography on a computer at work. The employer decided to make copies of the suspect’s hard drive and delivered them to the FBI. Ziegler filed a motion to suppress the evidence because his Fourth Amendment rights had been violated. A motion in limine is a request by a lawyer to hold a hearing before a trial, in an effort to suppress evidence. That evidence could include expert witness testimony. If this motion is successful, the jury will never see the evidence. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals agreed that the employee did have an expectation of privacy. However, warrants apply to government agents, and the employer was not acting as an agent of the government or in response to a request from a government agent.

It is important to understand that a warrant is specific to a particular crime and criminal investigation and is very specific to a geographic location. For example, if a house borders two counties, then two separate warrants are necessary to search the entire property. This specificity cannot be overemphasized. In one case, law enforcement was issued a warrant to search a house. When investigators arrived at the house, they realized that the suspect’s computer was located in a shed at the back of the house. Therefore, investigators were not permitted to search the location of the computer and could not seize the computer.

The Fourth Amendment states the following:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects,[a] against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

The scope of a warrant is narrow, which means that even with probable cause, a government is limited to a specific place, person, and thing(s) to be searched. A Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeal’s decision in 2008, and other decisions, have made this fact clear. Federal investigators successfully obtained a search warrant from the Central District Court of California to investigate the records of 10 Major League Baseball (MLB) players suspected of taking steroids kept at Bay Area Laboratories Company (BALCO). Federal investigators subsequently searched records of steroid use involving many more MLB players. Even though investigators tried to argue that the records of other players not noted in the initial warrant were in plain view, the majority of Ninth Circuit judges ruled that the investigators went too far. The court’s majority noted the following:

We accept the reality that such over-seizing is an inherent part of the electronic search process and proceed on the assumption that, when it comes to the seizure of electronic records, this will be far more common than in the days of paper records. This calls for greater vigilance on the part of judicial officers in striking the right balance between the government’s interest in law enforcement and the right of individuals to be free from unreasonable searches and seizures.

The ruling will naturally have implications for computer investigations going forward.

Warrantless Searches

Not all searches require a search warrant, however. With the passing of the USA PATRIOT Act, law enforcement has been provided with greater powers, which extends to warrantless searches when a person’s life or safety may be in danger. Exigent circumstances allow agents to conduct a warrantless search in an emergency situation when there is risk of harm to an individual or when there is risk of possible destruction of evidence. The case of United States v. McConney, 728 F.2d 1195, 1199 (9th Cir.), clearly details what is meant by exigent circumstances:

Those circumstances that would cause a reasonable person to believe that entry (or other relevant prompt action) was necessary to prevent physical harm to the officers or other persons, the destruction of relevant evidence, the escape of a suspect, or some other consequence improperly frustrating legitimate law enforcement efforts.

The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) provides guidelines for warrantless searches and seizures of computers at https://www.justice.gov/criminal-ccips/ccips-documents-and-reports.

When appropriate consent is granted to a government agent, a warrant is not required. Consent can be granted when an individual waives his or her Fourth Amendment rights. However, the search is limited to the physical area of the individual’s authority and is limited to a specific criminal investigation. A warrantless search is also subject to the totality of circumstances. This means that the individual granting consent must be of sound mind, must be an adult, and must be educated with a certain degree of intelligence.

Sometimes law enforcement uses a tactic known as a “knock and talk”. Knock and talk is when law enforcement does not have sufficient evidence or cannot demonstrate probable cause to enter a residence and execute a search. Instead, law enforcement personnel go to the suspect’s home and try to obtain the consent of the individual to gain entry to the home and conduct a consensual search. Sometimes this includes a non-custodial interview. This is an example of a warrantless search.

Plain view doctrine allows a government agent to seize evidence without a warrant when the officer can clearly observe contraband. To comply with this doctrine, an officer must be lawfully present in an area protected by the Fourth Amendment, the evidence must be in plain view, and the officer must immediately identify the item as contraband without further intrusion. These conditions of the plain view doctrine were affirmed in the case of Horton v. California.

Extending the scope of a warrant to include digital evidence in plain view can be extraordinarily difficult, however, as illustrated in the case of United States v. Carey (see United States v. Carey, No. 14-50222 (9th Cir. 2016)). Patrick Carey was under investigation for suspected possession and sale of cocaine. After a series of controlled drug purchases at his residence, police obtained an arrest warrant. Police asked Carey for consent to search his apartment. Concerned that his apartment might be trashed during a search, he signed a formal written consent. During the search, police seized drugs and two computers. Police subsequently obtained a warrant to search the computers for “names, telephone numbers, ledger receipts, addresses, and other documentary evidence pertaining to the sale and distribution of controlled substances”. Detective Lewis went through the computers’ files and noticed directories and files with sexually suggestive names. The detective opened an image file that was deemed to be child pornography. The detective continued with the search and downloaded 244 image files and viewed some more images of child pornography. Carey moved to suppress the images. The Tenth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals agreed with the defendant because, after viewing one image, the detective would have had an expectation of more child pornography on the computer and, therefore, required a new warrant to investigate a different crime. The warrant the detective had obtained was for a drug investigation, not for possession of child pornography.

In this case, the detective might have successfully argued his case that evidence of a crime was in plain view if the images had been displayed in the normal course of the investigation. In this case, the detective had been performing keyword searches to find evidence supporting his investigation of illegal possession and distribution of narcotics. You obviously would not be running keyword searches on images. A search warrant never allows investigators to conduct a general search.

The case of UNITED STATES of America, Plaintiff-Appellee, v. Russell Lane WALSER, Defendant-Appellant. No. 01-8019 is similar in nature. In June 2000, the manager of a hotel went to a guest room to check on a smoke alarm. While in the room, he noticed what he believed to be illegal drugs. He called the police, who then secured the room and obtained a search warrant for the hotel room. The warrant gave permission for the following search:

Controlled substances, evidence of the possession of controlled substances, which may include, but not be limited to, cash or proceeds from the sales of controlled substances, items, substances, and other paraphernalia designed or used in the weighing, cutting, and packaging of controlled substances, firearms, records, and/or receipts, written or electronically stored, income tax records, checking and savings records, records that show or tend to show ownership or control of the premises and other property used to facilitate the distribution and delivery [of] controlled substances.

The police searched the room, found illegal drugs and drug paraphernalia, and seized a computer in the room. Back at the forensic laboratory, during a search of the computer by Agent McFarland, the investigator stumbled upon what he believed to be child pornography. Agent McFarland ended his search and informed an investigator more familiar with child endangerment cases. The computer was shut down immediately, and another warrant was obtained. The defendant-appellant requested that the Tenth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals approve his motion to suppress the evidence garnered from the two searches of his computer, arguing that they lacked probable cause to do so. The court examined the case for plain error. Plain error arises when an appeals court identifies a major mistake made in court proceedings, even though no objection was made during the initial trial in which judgment was passed and a new trial was ordered. Under Rule 52(b), in the Rules of Criminal Procedure, a plain error that affects substantial rights may be considered even though it was not brought to the court’s attention. Rules of Criminal Procedure are protocols for how criminal proceedings in a federal court should be conducted. The defendant argued that the investigator who opened the .avi file, a video file, exceeded the scope of the warrant. He argued that a video file could not possibly have contained evidence relating to an investigation of drug possession, so the investigator should not have opened the file under the conditions outlined in the warrant. Based on the fact that the agent showed restraint in continuing his search, the court opined that the search was lawful and that the evidence was admissible.

This decision was in contrast to the Tenth Circuit Court’s decision earlier, in the case of United States v. Carey, when a police search of the suspect’s computer was deemed to be overly broad. We can therefore conclude that warrants must be specific to a particular criminal investigation and if, in the normal course of an investigation, the investigator inadvertently finds contraband unrelated to the initial investigation, the investigator should immediately cease the search for new contraband and obtain a new search warrant.

Interestingly, in the case of United States v. Mann (No. 08-3041), the Seventh Circuit Court upheld an earlier conviction in the case of a lifeguard instructor named Matthew Mann. He was investigated after video cameras were found in a locker room where women were changing clothes. Police obtained a warrant to search for computers and storage media. During the investigation, police found child pornography on the suspect’s hard drive, and Mann was subsequently charged. Mann filed a motion to suppress this evidence, but the Seventh Circuit Court opined that the search was not overbroad, even though the images of children were specially flagged by investigators, who knew that they were now working on a different investigation. Nevertheless, given previous decisions, it does seem wise for law enforcement to err on the side of caution and obtain a warrant before continuing a search related to a different crime.

The case of People v. Diaz is an interesting case that deals with a warrantless search of a suspect’s cellphone. The Supreme Court of California upheld the Court of Appeals decision that a warrantless search of text messages is lawful after an arrest. Diaz was arrested after selling drugs to a police informant. Upon arrest, the suspect’s cellphone was seized, placed into evidence, and searched. The defense moved to suppress the cellphone evidence, but the court sided with law enforcement, citing that it was incident to arrest. A subsequent ruling, with Riley v. California, which was a landmark Supreme Court decision in 2014, held that a warrantless search of a cellphone, incident to arrest, is illegal. Search incident to a lawful arrest allows law enforcement to conduct a warrantless search after an arrest has been made. The search is limited to the individual and her surrounding area and may include a search of the suspect’s vehicle (see Arizona v. Gant, 2009).

Law enforcement may also be able to acquire evidence without a warrant via a third-party. For example, a service provider might offer evidence for a suspect, or text messages or email could be acquired from a victim. In these situations, the suspect has no standing. Standing refers to a suspect’s right to object to a Fourth Amendment search, as outlined by the Supreme Court.

When Does Digital Surveillance Become a Search?

Two recent court cases bring into question the rights of an individual and the expectations of government agents during an investigation. In all but one of the following cases, the convicted criminals were involved in some appalling criminal activities.

In the case of U.S. v. Daniel David Rigmaiden, 844 F.Supp.2d 982 (2012), the suspect was charged with financial fraud. Between January 2005 and April 2008, Rigmaiden allegedly acquired $4 million from fraudulently filing 1,900 tax returns. The case was tried in the U.S. District Court of Arizona. Law enforcement located the suspect using a “Stingray” device. Stingray is the generic name given to a device that acts like a cellphone tower to locate criminal suspects but can also be used to locate people in disaster areas, such as earthquakes. In the case of Rigmaiden, federal agents were able to locate him based on a Verizon broadband card, which operates on a cellphone network.

The defense argued that federal agents required a search warrant to use the device. In addition, they argued that they had a right to view the Stingray used to capture the suspect. The prosecution contended that the use of a pen register requires only a court order, not a warrant. A court order is issued by a court and details a set of steps to be carried out by law enforcement; it is easier to obtain than a warrant because probable cause need not be demonstrated. A pen register is an electronic device that captures telephone numbers. Pen register orders require law enforcement to show only that information retrieved is likely to assist in an ongoing investigation. Rules governing the use of a pen register can be found in 18 U.S.C., Chapter 206. A pen register is not a search, as opined by the Supreme Court in Smith v. Maryland, 442 U.S. 735 (1979). The defense counsel argued that the Stingray cannot be classified as a pen register device because the device also records the location of people. The defense counsel also argued the legality of the prosecution using the device, expunging the device of evidence, and not allowing the defense to view the device. The prosecution did not want to show the device because it is a “secret device” and the evidence was regularly scrubbed from the device because the device would also record the information of innocent cellphone users. The Department of Justice later admitted that it conducted a search but still contended that, when using a cellphone (or a broadband card), there is no expectation of privacy. The prosecution also stated that a court order did allow investigators to capture real-time data from Verizon. Nevertheless, the suspect was found in his apartment. A search warrant for the apartment was later obtained.

GPS Tracking

The use of GPS tracking devices is prevalent and widespread, but only recently has the legality of these devices come to the fore. Yasir Afifi, a 20-year-old Arab-American student, was the son of an Islamic-American community leader. Afifi was surfing the Internet when he noticed a piece about GPS tracking devices. On a whim, he checked his car and noticed a wire sticking out. Afifi found the device on the undercarriage of his car and had it removed. The device, known as the Orion Guardian ST820, is manufactured by Cobham PLC.

FBI agents showed up at the student’s house and demanded the expensive, secretive device back. Afifi complied with their demand. Interestingly, the Ninth Circuit Court opined that attaching the device was not illegal and did not require a warrant, even if the device was attached to the car while in a person’s driveway. Afifi’s driveway was not enclosed and did not pass the Dunn test for Curtilage. Curtilage refers to the property surrounding a house. In the case of U.S. v. Dunn, 480 U.S. 294 (1987), Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) agents used electronic tracking devices in an electric hot plate stirrer, a drum of acetic anhydride, and a phenylacetic acid container. Agents noticed from aerial photographs that the suspect backed his truck up to a barn on his ranch. The entire ranch perimeter was enclosed by a fence and barbed wire. Agents crossed a perimeter fence and an interior fence, looked through the window of a barn, and spotted a methamphetamine laboratory in the barn with the use of a flashlight. They subsequently entered the barn to confirm the existence of the laboratory. They then obtained and executed a search warrant. The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the Dunn conviction because agents had entered the ranch without a warrant, and the barn was within the protected curtilage. The U.S. Supreme Court reversed the decision and opined that the barn was not within curtilage because it was not used for intimate activities. They stated that the agents in “open fields” were no different than being in a public place.

In a similar case, U.S. v. Knotts 460 U.S. 276 (1983), Minnesota police placed a radio transmitter (beeper) inside a chloroform container. The suspect, Armstrong, was suspected of using chloroform to manufacture illicit drugs. The Federal District Court denied the defendant’s motion to suppress the evidence obtained from the beeper. Later the Court of Appeals reversed the decision of the Federal District Court. The case was subsequently heard by the Supreme Court, which reversed the Court of Appeals decision and upheld the original conviction. In the majority opinion:

Monitoring the beeper signals did not invade any legitimate expectation of privacy on respondent’s part, and thus there was neither a “search” nor a “seizure” within the contemplation of the Fourth Amendment. The beeper surveillance amounted principally to following an automobile on public streets and highways. A person traveling in an automobile on public thoroughfares has no reasonable expectation of privacy in his movements.

The use of GPS tracking devices has come up numerous times in case law. In U.S. v. McIver, law enforcement attached a tracking device to McIver’s car while it was parked in front of his garage. McIver was suspected of growing marijuana. The court deemed the car to be outside the curtilage of his home and was therefore not deemed a search. They also noted that “[t]he undercarriage is part of the car’s exterior, and as such, is not afforded a reasonable expectation of privacy.” The case of U.S. v. Pineda-Moreno was very similar, and the case was heard by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. The DEA noticed the suspect purchasing large quantities of fertilizer from a Home Depot and suspected that he was using it for growing marijuana. On seven different occasions, a GPS tracking device was attached to the suspect’s Jeep, once when the car was parked in the owner’s driveway. Agents pulled the suspect’s car over, smelled the odor of marijuana, and asked the suspect for permission to search the vehicle. The suspect allowed the agents to search the car, and they found two large trash bags filled with marijuana. The suspect was then indicted by a grand jury. Defense counsel filed a motion to suppress the evidence on the basis of a Fourth Amendment violation and entered a conditional plea of guilty with the District Court. The Ninth Circuit ruled that the car was within the curtilage of the home, which “is only a semiprivate area” (see United States v. Magana, 512 F.2d 1169, 1171 [9th Cir. 1975]). The court also noted that the “undercarriage of a vehicle, as part of its exterior, is not entitled to a reasonable expectation of privacy.”

In the case of United States v. Jones, the D.C. Circuit Court was asked to hear the case of Antoine Jones, concerning a GPS tracking device that was used. Jones was suspected of distributing narcotics. Agents secured a Title III wiretap, which allows for electronic surveillance. A D.C. federal judge issued a warrant to covertly install a GPS tracking device on Jones’s Jeep Cherokee within 10 days of the warrant issue date. However, agents did not install the device until the 11th day. Agents later seized 97 kilograms of cocaine and $850,000 from the suspect’s home. The U.S. District Court (D.C.) found Jones guilty of conspiring to sell cocaine and he was sentenced to life in prison. However, a Court of Appeals later reversed the decision. The D.C. Circuit Court noted that the Knotts decision did not apply because Jones was under constant surveillance. The court opined:

The Court explicitly distinguished between the limited information discovered by use of the beeper—movements during a discrete journey—and more comprehensive or sustained monitoring of the sort at issue in this case.…Most important for the present case, the Court specifically reserved the question whether a warrant would be required in a case involving twenty-four hour surveillance, stating, “if such dragnet-type law enforcement practices as respondent envisions should eventually occur, there will be time enough then to determine whether different constitutional principles may be applicable.”

The case was then referred to the U.S. Supreme Court, and because the warrant had expired when the device was attached, the question became whether a warrant was necessary. During oral arguments, it was clear that this case is different from other cases involving the warrantless use of tracking devices. Justice Sonia Sotomayor stated the following:

What motivated the Fourth Amendment historically was the disapproval, the outrage, that our Founding Fathers experienced with general warrants that permitted police indiscriminately to investigate just on the basis of suspicion, not probable cause, and to invade every possession that the individual had in search of a crime.

Justice Samuel Alito took quite a different view of the use of tracking devices, in a digital age when so much of our personal information is freely available on social networking websites:

“With computers around, it’s now so simple to amass an enormous amount of information. How do we deal with this? Just say nothing has changed?”

Justice Elena Kagan noted that times have changed and that many cities have numerous speed and surveillance cameras.

The use of GPS surveillance devices has clearly become a contentious issue, and there is a distinct lack of clarity in case law. Under Knotts, law enforcement may be able to install GPS tracking devices even if the installation occurs on a driveway, generally deemed by the courts to be outside of the privacy of one’s home, in a semi-private area and not protected under the Fourth Amendment.

In January 2012, the Supreme Court unanimously decided that government agents violated Jones’s Fourth Amendment rights. However, the justices’ reasoning for doing so was split 5–4. The majority ruled that the search was illegal because they deemed that the agents had trespassed. Justice Alito, a conservative, and three other justices went as far as to say that Jones’s expectation of privacy was violated, although Justice Scalia and four others did not agree.

The U.S. v. Jones Supreme Court decision has had repercussions for the GPS surveillance of criminal suspects. GPS tracking constitutes a search and seizure. Justice Scalia noted the following in the decision:

We decide whether the attachment of a Global Positioning-System (GPS) tracking device to an individual’s vehicle, and subsequent use of that device to monitor the vehicle’s movements on public streets, constitutes a search or seizure within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment.

An interesting part of this case are the opinions of the Supreme Court justices, who appeared to be voicing the opinions of divided public opinion and considering whether it is right to sacrifice our expectation of privacy in a digital age.

GPS Tracking (State Law)

A number of states prohibit the use of GPS tracking devices without a warrant. In the case of Oregon v. Meredith, a transmitter was attached to a United States Forest Service (USFS) truck. The suspect was caught setting a fire and was charged with arson. In this case, the lower court agreed with the defense’s motion to suppress evidence derived from the transmitter. The Supreme Court of Oregon disagreed because the defendant did not have an expectation of privacy when using the vehicle in public. Moreover, the defendant was using the employer’s vehicle. The use of the monitor did not constitute a “search” under Article 1, Section 9, of the Oregon Constitution.

There was a slightly different opinion, however, in the case of Washington v. Jackson, 150 Wash.2d 251, 76 P.3d 217 (Wash. 2003). Under Article 1, Section 7, of the Washington Constitution, GPS tracking is unlawful without a warrant. GPS tracking is viewed as an intrusion into someone’s life. The court ruled that law enforcement did have a warrant to use GPS tracking and that it was the only reasonable way to track the two vehicles needed to track the suspect.

The New York Constitution prohibits the use of GPS tracking devices without a warrant. In the case of New York v. Weaver, a police officer attached a GPS device to a suspect’s van bumper in connection with a series of burglaries. The defendant and code-fendant were arrested and charged with burglary in the third degree and grand larceny in the second degree. The New York Court of Appeals opined:

Technological advances have produced many valuable tools for law enforcement and, as the years go by, the technology available to aid in the detection of criminal conduct will only become more and more sophisticated. Without judicial oversight, the use of these powerful devices presents a significant and, to our minds, unacceptable risk of abuse. Under our State Constitution, in the absence of exigent circumstances, the installation and use of a GPS device to monitor an individual’s whereabouts requires a warrant supported by probable cause.

The State of Ohio has upheld the warrantless use of GPS tracking devices. In Ohio v. Johnson, agents attached a tracking device to the undercarriage of a suspected drug dealer’s van. Police later stopped Johnson’s van, and the suspect admitted that he was on his way to sell cocaine. The court opined,

“Johnson did not produce any evidence that demonstrated his intention to guard the undercarriage of his van from inspection or manipulation by others.…Supreme Court precedent has established not only that a vehicle’s exterior lacks a reasonable expectation of privacy, but also that one’s travel on public roads does not implicate Fourth Amendment protection against searches and seizures.”

Traffic Stops

The acquisition of digital evidence during a traffic stop can appear somewhat confusing when perusing case law. Surprisingly, Michigan State Police occasionally performed warrantless searches of drivers’ cellphones during traffic stops, using the Cellebrite UFED, which has the ability to capture evidence from thousands of different cellphone models. You might expect that these types of searches required a warrant, but certain types of warrantless searches can be conducted incident to arrest.

In the case of California v. Nottoli, policed stopped the suspect, Reid Nottoli, after speeding on a highway in his silver Acura TL. Santa Cruz County Deputy Sheriff Steven Ryan suspected that Nottoli was driving under the influence of a drug but was not driving while impaired. Nottoli’s license was also expired. Ryan informed the driver that his car would be impounded. Nottoli was placed in handcuffs and then put in the patrol car. Ryan decided to take an inventory of the vehicle’s contents before having it towed. During the search of the vehicle, he found a Glock 20 handgun with a Guncrafter Industries conversion, which meant that it should have been secured in the trunk of the car. Deputy Gonzales, who had later arrived on the scene, noticed a BlackBerry Curve cellphone in a cup holder. He pressed a button on the BlackBerry to see if it was functional and noticed a wallpaper image of a man wearing a mask holding two AR-15 assault rifles in akimbo fashion. The officer suspected that the individual in the picture was Nottoli. These rifles had been legal in California before the weapons ban, but Ryan confiscated the cellphone as evidence of possible “gun-related” criminal activity. The officer viewed pictures, emails, and text messages for approximately 10 minutes, according to court documents.

Only after this initial search did Ryan secure a search warrant for the cellphone and a second search warrant for Nottoli’s residence. SWAT personnel were sent into the home based on suspected drug-related information retrieved from the cellphone. Law enforcement seized $15,000 and a large cache of weapons and discovered a marijuana-growing operation. Nottoli filed a motion to suppress the evidence based on a violation of the Fourth Amendment, a warrantless search of the cellphone. At the initial trial, the magistrate agreed that the officers did not have a right to search the cellphone without a warrant:

I think there was an expectation of privacy that the defendant had for his BlackBerry, that there were not sufficient grounds to authorize the deputy to open that BlackBerry up and, therefore, anything that was discovered as a result of that activity would be suppressed.…

In South Dakota v. Opperman (1976) 428 U.S. 364 [96 S.Ct. 3092], the Supreme Court held that “a routine inventory search of an automobile lawfully impounded by police for violations of municipal parking ordinances”, consistent with “standard police procedures”, was reasonable under the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

The Court of Appeals of the State of California ruled that the deputies were justified in searching the vehicle’s passenger compartment and, ‘any containers therein’, based upon the Supreme Court decision on Arizona v. Gant. The court continued, with Justice Franklin D. Elia writing for the three judge panel:

In sum, it is our conclusion that, after Reid [Nottoli] was arrested for being under the influence, it was reasonable to believe that evidence relevant to that offense might be found in his vehicle. Consequently, the deputies had unqualified authority under Gant to search the passenger compartment of the vehicle and any container found therein, including Reid’s cell phone. It is up to the US Supreme Court to impose any greater limits on officers’ authority to search incident to arrest.

Many lawmakers were incensed by this decision. The California State Senate and Assembly then passed a bill requiring that a warrant be required before carrying out a search of a cellphone. Surprisingly, California Gov. Jerry Brown then vetoed the bill. Brown wrote in his message to the Senate, “I am returning Senate Bill 914 without my signature” and stated that the “courts are better suited to resolve the complex and case-specific issues relating to constitutional search-and-seizures protections.”

The case of New York v. Perez (2011 NY Slip Op 07659), had a different outcome. The defendant was found guilty in Suffolk County Court, New York, of criminal possession of a controlled substance in the first degree, false personation, operating a motor vehicle while using a mobile telephone (under Vehicle and Traffic Law § 1225-c(2)(a)), operating a motor vehicle without using a safety belt (under Vehicle and Traffic Law § 1229-c(3)), and failing to stay in a designated lane (under Vehicle and Traffic Law § 1128(a)). Police stopped the defendant and impounded the vehicle. While the vehicle was impounded, an officer searched the vehicle and leafed through a notebook. The notebook indicated the possible presence of narcotics in the vehicle. Police returned with a canine to help locate the suspected drugs. Police then pried open a compartment and found bundles of secreted cash. The New York State Supreme Court overturned the lower court’s decision and found that the defendant’s Fourth Amendment rights had been violated with an illegal search. With the car impounded, there was “ample time for the law enforcement officials to secure a warrant in order to make this significant intrusion” (People v Spinelli, 35 NY2d 77, 81). The defendant’s statements were suppressed after the illegal search as fruit of the poisonous tree.

In the case of Riley v. California, 573 U.S. 373 (2014), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2014 that police require a warrant to search the cellphone of someone who is arrested. This was a landmark decision for law enforcement and forensics investigators because a cellphone can no longer be searched incident to arrest.

Carpenter v. United States

In the case of Carpenter v. United States in 2018, a 5–4 Supreme Court decision, authored by Chief Justice Roberts, stated that when the government obtains historical cellphone records that contain cell site location information (CSLI), without a warrant, then they are violating the Fourth Amendment.

The case stemmed from armed robberies at a RadioShack and a T-Mobile store in Michigan. The four thieves were caught and arrested. The FBI obtained call logs from one of the robbers, which ultimately included call logs from Timothy Carpenter, the Petitioner in this case, who was not one of the robbers. Historical cell-site location information (CLSI) data tracked Carpenter for 127 days—an average of 101 data points per day. In the Supreme Court opinion for this case, Roberts cited the previous court decision in United States v. Jones, 565 U. S. 400, whereby concerns were raised with GPS tracking. Again, the data derived from cell-sites could be used to track Carpenter’s location over a 127-day period. The opinion stated:

Tracking a person’s past movements through CSLI partakes of many of the qualities of GPS monitoring considered in Jones. In fact, historical cell-site records present even greater privacy concerns than the GPS monitoring considered in Jones: They give the Government near perfect surveillance and allow it to travel back in time to retrace a person’s whereabouts, subject only to the five-year retention policies of most wireless carriers.

Furthermore, the opinion (18 U. S. C.§2703(d)) noted: