2

LEARNING FROM WINNERS

A single conversation with a wise man is better than ten years of study.

—Chinese proverb

Every leader is tasked with getting from Point A to Point B.

The leaders I work with tell me it’s their most significant objective and the hardest to achieve, and accountability is the single greatest threat to reaching Point B.

In the previous chapter, you were prompted to consider your personal Point B.

In this chapter, we consider Point B from the perspective of the enterprise you are leading.

Whether you are in charge of a corporation, a partnership, a business unit, a department, a single project, or a not-for-profit organization, you must marshal the resources of your team to move from Point A (your current situation) to Point B (your objective).

Accountability is an obstacle in your path. More times than not, it’s the obstacle in your path.

My interviews with senior leaders at high-performing companies and my 30 years of working with leadership teams in dozens of industries indicate that all organizations wrestle with accountability in much the same way. Data I have collected from executives worldwide over a five-year period support my observations.

What separates high-performing organizations from average ones? What factors propel some firms to winning heights?

As discussed in the previous chapter, accountability starts with knowing who you are, what you want, and what you don’t want.

In this chapter, we begin our examination of how leaders at high-performing companies transfer their personal accountability to their entire organization to achieve exceptional results.

A CULTURE, NOT A TECHNIQUE

Even though you will not find a silver bullet to achieve high levels of accountability, high-performing organizations have in common a way of doing things that distinguishes their culture.

We will examine how high-performing organizations create and sustain a culture of purpose, accountability, and fulfillment, and equip you with a set of principles and practices to help you drive accountability in your organization.

If you are expecting tips and techniques for having a tough conversation about accountability, you will miss the bigger point. Yes, we examine a model for a conversation with an underperformer in Chapter 9, but long before that conversation occurs dozens of other practices must be in place if you expect to drive accountability throughout your organization to create and sustain a high-performance culture.

You will meet leaders at these high-performing companies who, in describing their approach to accountability and performance, use phrases such as “It’s not rocket science,” “It’s really pretty simple,” and “You’ve heard this before.” The key to accountability is bringing together these principles and then acting on them with consistency and urgency.

Let’s look first at why accountability continues to be a problem for so many leaders.

ACCOUNTABILITY’S CHOKEPOINT

All organizations wrestle with accountability in much the same way. Although the scope and complexity may differ from organization to organization, the problems leaders encounter on their journey from Point A to Point B are similar.

Every organization deploys three fundamental resources: time, people, and money. (You may be tempted to include equipment, inventory, or real estate holdings, but these inanimate items are purchased. And while you also may be tempted to argue that people are purchased because you pay them a salary, you don’t own them and they are free to leave anytime they wish.)

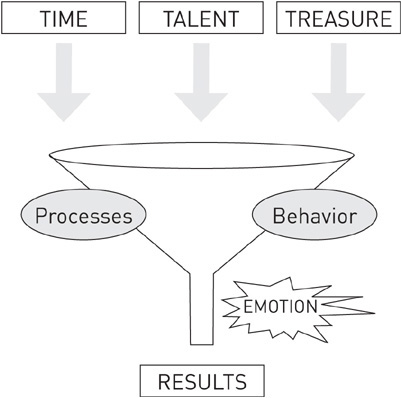

Think of your organization as a funnel into which time, talent (people), and treasure (money) are poured.

Figure 2.1 Performance Funnel

Emerging from the funnel’s spout is the result of your investment in those three commodities. The result may be satisfactory or unsatisfactory. As time, talent, and treasure move through your funnel toward a result, their original state is altered as they come into contact with one another. This contact is shaped by two key contributing factors: the processes inside your organization (your belief systems, policies, operating procedures, and technical support systems that form the infrastructure of your organization), and the behavior of people comprising teams, departments, remote locations, business units, and outside suppliers (it’s the rare individual who works in solitary confinement). The sum of this behavior is your organization’s culture.

For many leaders and their organizations, the narrowest point of the funnel is a chokepoint because it’s a place where emotions can enter into decision making and influence the results. Emotions can prevent successful leaders from holding themselves, their peers, and those who report to them accountable. And when that happens, the results can be less than satisfactory.

Part of what makes accountability difficult is that when you are working with smart people and things don’t get done well or on time, you are often handed excuses. Here’s what lack of accountability sounds like:

Time

I rush from one fire to the next, so there’s no time to work on my project.

Our deadlines are unrealistic.

The deadline was unclear.

I spend my time doing my boss’s work.

I spend my time doing work my staff should be doing.

I have to spend my time on tactical—not strategic—work.

We’re always in a hurry, but when we hurry we make mistakes and have to do the work again.

There’s no sense of urgency around here.

I ran out of time.

His performance will improve with time.

Talent

We don’t have the right people.

We don’t have enough people.

We don’t have enough of the right people.

The people on our team can’t think for themselves.

He let me down.

These people don’t report to me, so I have no control on work product.

I didn’t know I was allowed to make that decision.

I didn’t understand the assignment.

It wasn’t my job.

The changes we made are preventing me from getting things done.

My team won’t like me if I confront their performance issues.

The people here are not team players.

That person is a family member and the rules don’t apply to her.

We can’t seem to keep our best people so we are not very effective.

Treasure

We underprice projects (or products) so we can’t staff properly for the work (or products) we have agreed to deliver.

We can’t agree on priorities so our budgets are spread too thin.

Our customers beat us up on price so we can’t possibly charge more.

We are constantly being asked to do more with less, including more work for the same salary.

Money is tight so we can’t hire the people we need.

It is a vicious circle, and the excuses are infinite. Talk is cheap so we often buy it.

When we do, accountability suffers. And even though accountability is a significant component of any leader’s success, it is not even your biggest problem. Your biggest problem is reaching Point B.

THE LEADER’S BIGGEST PROBLEM

If you have visited Provence, you may have taken the opportunity to view one of the most picturesque sites in all of France: the Gorges du Verdon, the “Grand Canyon of France,” a 13-mile (21-kilometer) scenic stretch of rock and water considered to be one of the world’s natural masterpieces.

On our trip, my wife, Janet, noted two routes we could take to reach our next destination—one route took us around the canyon, the other across. Janet and our daughter, Jordan, were excited about what lay ahead. I am petrified by heights and asked if our route would be taking us across the abyss. Knowing my fear, Janet replied that she wasn’t sure which route would get us to our destination, which I immediately should have taken as code for “Yes, we’re going to cross the canyon!” and handed her the car keys. Instead, I remained at the wheel while Janet consulted the map and provided driving directions.

Rounding a turn, there it was: Europe’s greatest canyon. We have visited the Grand Canyon in Arizona, but this view literally took my breath away—partly because of its awesome beauty, and partly because I now knew for certain we were about to drive across Europe’s deepest canyon to reach our destination.

To give you some idea of what we were facing, the gorges drop 2,200 feet (670 meters) to the Verdon River at their deepest points, and at their widest points, the walls of the canyon are 4,700 feet (1,433 meters) apart. This height is roughly equivalent to the Empire State Building and Chrysler Building stacked one on top of the other.

Guidebooks call the route along the canyon corniche sublime (literally, “heavenly ledge”), but I call it corniche de la terreur (“ledge of terror”). The bridge we were to cross, the Pont d’Artuby, spans a place in the canyon where the walls are only 350 feet (197 meters) apart, but to me it looked like a mile. The bridge itself is an engineering marvel constructed of reinforced concrete and was completed in 1940. I like bridges close to the ground and supported by pillars to assure me they won’t collapse as I cross, but this bridge consists of a single arch. To my nonengineering mind, the bridge seemed to have little visible support as it rose 410 feet (125 meters) above the canyon floor, the equivalent of a 27-story building.1 Not exactly a high-rise, but plenty tall for a guy scared of heights. I was paralyzed with fear.

So at a pullout near the bridge, Janet took the wheel, Jordan hopped in the passenger side, and I cowered in the backseat. As we were about to cross the abyss, Jordan said, “Close your eyes, Daddy, and don’t worry—it will all be over in 12 seconds.”

“I know,” I replied, “that’s what I’m worried about.”

CROSSING THE ABYSS

It is obvious that we made it across the abyss, over the bridge, and onto our next destination, but my experience illustrates the biggest problem every leader faces: Starting at Point A and then crossing the abyss to reach Point B. As a leader, your vision is an exciting journey filled with wonderful experiences, a setback or two along the way, some exhilarating moments, but overall a great adventure capped by the emotional and financial rewards that come with fulfilling a dream. To others, your vision is downright scary.

To cross the abyss, your first challenge is to help those on your team see that it is both necessary and possible to get to the other side. They not only need to share your vision, they need to believe it. Doing so can be a challenge, though the idea of a better future is usually greeted with approval. In my case, I wanted to reach our next destination, but the journey across the bridge was terrifying.

Many people will share your enthusiasm for the journey ahead and can’t wait to get going. Just as players of Texas Hold ’em respond to a great poker hand by betting all their chips, going “all in,” so, too, do the leaders on a winning team respond to a clear vision they believe in with their full commitment. Unfortunately, those who share your enthusiasm are usually outnumbered by those who do not.

It is likely that some on your team listening to you describe Point B are thinking, “Wow, that’s really going to take some work to get from Point A to Point B. I’m not sure if we can do it.” They will be taking a wait-and-see approach to determine your conviction. Others may think, “I can do this, but I’m not sure I trust everyone on this team to help us achieve this vision.” And just as I asked at Pont d’Artuby, some may wonder, “Why do we need to go this way?” Finally, others may resent this change and ask, “Why do we need to go at all? I’m comfortable where I am.” Those in this group may even try to undermine efforts to move to Point B.

You will need everyone’s help achieving the organization’s vision, not just a select few. So your second job as the leader is to bring everyone along so that they, too, believe in the vision and commit to achieving it. People are more likely to support a plan they helped develop, so guide your team through the development of a plan that shows how you will cross the abyss and get from Point A to Point B. Your plan should include objectives, strategies, budgets, responsibilities, and schedules. Be honest about the problems you foresee and make specific plans ahead of time for how those obstacles will be addressed. Sugarcoating difficulties does not build trust.

Your plan is your road map. It’s also your contract with each other.

Without a plan, expectations are not clear. And without clear expectations, accountability is not possible.

PLANNING IS TRUST-BUILDING

When I lead strategic planning sessions with leadership teams, philosophical differences frequently expose themselves. These differences can include lack of alignment on these significant issues:

![]() Company direction

Company direction

![]() Financial objectives

Financial objectives

![]() Organizational structure

Organizational structure

![]() Talent development

Talent development

![]() Growth strategies

Growth strategies

![]() Rewards and penalties

Rewards and penalties

Differences may show up in other ways. Some people may not trust the CEO to carry out tough decisions, including addressing underperformance. Some may question whether the CEO will follow through with promised rewards (i.e., money, increased responsibility, approval to hire a star, etc.) commensurate with the emotional investment, hard work, sacrifice, and discipline required to accomplish stated objectives. Others may not trust peers to behave in a manner consistent with the organization’s values. Still others may doubt the ability of a peer to perform at the higher level now required by the firm’s trajectory.

These issues are all rooted in trust, which is why I believe the process of planning for the future is less about list-building and budget-building and more about trust-building. To achieve the objectives you and your team say you want, you must trust one another’s character and competency.

Alignment does not mean absence of conflict. Just the opposite. Authentic alignment is achieved only when conflict is encouraged, options for resolving the conflict are weighed, and a solution is reached that all leaders support. Debate is healthy. Argument is not.

For healthy conflict to occur, leaders must trust each other. Think about it: You don’t talk openly and candidly about problems, fears, and controversy with people you don’t trust and care about.

If you are not talking about real issues, your planning process is going to be a waste of time and you might as well give up on the idea of holding people accountable.

Trust and purpose are the cornerstones on which you will build your team, your organization, and a future of high performance.

ACCOUNTABILITY’S OTHER SIDE

Ron Farmer founded US Signs in 1980 and led his company through nine tough months the company’s first year as well as through three recessions before selling his company in 2011 for full value. Growing more than 1,000 percent in the first 5 years landed US Signs on the Inc. 500 list at #196. Farmer started a second company, US LED, in 2001, and he and his team achieved average annual growth rate of 73 percent over the first 10 years. In 2012, he was an Ernst & Young Entrepreneur of the Year finalist.

Like many of the leaders I interviewed, Farmer believes accountability has two sides: a positive side and a negative side.

Accountability gets a bad rap. Just saying the word conjures all sorts of negative images: micromanagement; an emotional, mean-spirited conversation; punishment. It can be all of those things, but it doesn’t have to be any of them.

“People do their best work,” Farmer told me, “when they know they’re going to be given credit for their contribution. So there has to be a certain amount of autonomy in people’s work so they can contribute without reservation. There’s accountability at work in this type of approach, but I view accountability not from the side that says, ‘This is what happens if you don’t do something,’ but rather, ‘See what’s possible if you do your best.’ It’s the other side of the same coin.”

To Farmer, accountability with autonomy can be exciting to people.

“If people don’t have a sense of accountability—to themselves and to each other—they don’t warrant having autonomy,” he says. “And when creative, self-referenced people do have autonomy, they have the incentive, the energy, and the enthusiasm to do their best. They’re proud of their accomplishments and love being given credit for their contributions.

“Teamwork is great,” says Farmer, “but even within the team you need to have enough of an understanding of human beings’ need for individual contribution and recognition because people—most people, the kind of people we hire—crave challenging work so they can develop a mastery of something that counts … something they can point to with colleagues, spouses, and friends. These people have a sense of ownership, a sense of pride. And so on the one hand, you’re holding them accountable; on the other hand, you’re rewarding them with the freedom to be their best. So the accountability structure is really a recognition structure. I would rather talk to my employees about a recognition program than about an accountability structure with negative implications.”

It is the leader’s job to make accountability a support structure, not a blame structure.

GETTING COMFORTABLE WITH CHANGE

If you don’t plan to change, don’t bother to plan.

Planning, by definition, means doing more of what’s working and less of what isn’t.

So the planning process should be expected to identify people, processes, and programs that are delivering high levels of performance, as well as those that no longer serve the enterprise or are inefficient.

Tackle change head-on and expose difficult issues that must be addressed if the company expects to improve its financial and operational performance. Leaders in these sessions talk openly, perhaps hesitantly at first, but then more confidently as the session continues, about fixing problems, replicating successes, and carving up sacred cows.

At the conclusion of these debates, a choice must be made. Those who agree with the decision are prepared to be held accountable by colleagues and likewise are prepared to hold colleagues accountable for implementing the plan.

Southwest Airlines has built a reputation as a great place to work and a great airline for travelers because of its emphasis on doing things differently, caring about people, and having fun. But the company is completely serious when it comes to saying what you mean and meaning what you say.

“We care enough about each other to tell the truth,” says Elizabeth Bryant of Southwest Airlines, who, as vice president of the company’s training initiatives, is responsible for nurturing the culture among Southwest’s nearly 46,000 employees. “So if we really care about each other,” she told me, “we must have the courage to be honest with each other. Because if we only focus on having a conversation when things are going well, then we’re not sharing the whole picture.”

When differences are not resolved, any person who disagrees with the situation—whether the disagreement is philosophical, financial, strategic, or cultural—is out of alignment with the top decision makers’ view of the situation. It is difficult to be committed to something you don’t believe in.

“As a rule, people don’t leave Herman Miller because of poor skills as much as they do because of poor behavior,” says Tony Cortese, who, as the organization’s senior vice president of human resources, guides employee-related strategies for the $1.6 billion company whose furniture is sold in 100 countries.

“Behavior and cultural issues probably account for the majority of terminations at Herman Miller,” Cortese told me. “It’s not often that it’s a skill- or competency-based issue. I’ve seen some very competent people who just didn’t navigate our culture well.”

The company’s structure is characterized by a certain amount of ambiguity because of its ad hoc teams and a “distributed leadership model,” and Herman Miller recognizes that some people are more comfortable in highly defined structures and can’t handle ambiguity. “When you get into those situations,” says Cortese, “the people involved are professional and they will start to feel, ‘Maybe this isn’t the right fit.’ We may have that same impression, and that will begin to lead to a mutual understanding and parting of our ways.”

ALL IN OR PLAYING ALONG?

In good times with plenty of good jobs available, a worker—whether it’s a top executive or a member of the rank-and-file—will simply say, “I don’t agree with the decisions that have been made and I’ve found another company that suits me better. I’m outta here!”

When people leave because they no longer agree with where things are going or how things are done, their departure should be viewed as a happy event for all.

Trouble occurs when disillusioned and unproductive employees don’t leave.

When the market is down, plenty of unhappy, disengaged workers go through the motions in their jobs. These people are technically okay at what they do but are not as committed to an organization’s mission and their colleagues’ success as they are to their own preservation. These employees have been waiting for the market to improve so they can move on. Or, worse, they have quit their job but are still collecting a paycheck while they work against your improvement initiatives.

For whatever reason, these employees no longer agree with nor are they passionate about the mission, vision, values, or strategy of their current organization. They are playing along.

No one wants a disgruntled person on their team. People who are unhappy should go for their sake as well as for everyone else’s.

Let’s face it. If your biggest problem is getting from Point A to Point B, you want people on your team you can count on. Performing at high levels has never been tougher. You need full commitment, not halfhearted effort.

As you and your team start to execute your plan, plenty of external forces will be standing in your way. If you imagine your destination as a place on the opposite side of a deep abyss, why in the world would you want someone in your organization who has little interest in helping you make it across safely?

Jeff Bowling is the CEO of The Delta Companies. Bowling started in a 10 × 10-foot office in 1997 with a passion for finding a better way to provide healthcare staffing and treating employees better in the process. He now has a team of more than 200 engaged colleagues who help make The Delta Companies an industry top performer and one of the best places to work in Texas.

The Delta Companies operated under a parent company owned by an angel investor, and after six years the investor was ready to close the company and split the assets. Bowling proposed buying the company, and the investor—hardly an angel—gave Bowling just two weeks to secure funding.

Bowling asked friends and family to commit the money, including 10 of his colleagues who borrowed against their credit cards, took out loans, and agreed to work without pay. Looking back, Bowling says the commitment to one another was so high, “we never considered it a risk.”

But it was a sobering moment. “In that nanosecond,” Bowling told me, “I understood the new level of responsibility I was assuming because it wasn’t only me taking the risk. Others were also at risk. They were providing me a level of trust and they believed. I couldn’t let them down. It got real in a hurry.”

You and those on your team must be able to “get real” and count on one another. It is in such situations where the importance of accountability—or lack of it—brings your own workplace culture into sharp focus.

CULTURE TRUMPS STRATEGY

How your plan is executed reveals your organization’s culture.

“Culture eats strategy for breakfast,” said management guru Peter Drucker. Your culture—the sum of your behaviors—is what drives the satisfactory or unsatisfactory results you are getting.

For The Container Store, getting culture right was important from the beginning. “When The Container Store first opened its doors, it had the same culture then as we do now. Actually, the culture is stronger now,” said Casey Shilling, vice president of public relations and marketing communications who works directly with Tindell and who joined the company in 1997. With an investment of $35,000, Tindell (chairman and CEO), Boone (chairman emeritus), and architect John Mullen originated a new retailing concept: a store devoted exclusively to storage and organization. The first store opened on July 1, 1978, in a 1,600-square-foot retail space in Dallas and was filled with products such as commercial parts bins, mailboxes, popcorn tins, burger baskets, milk crates, and wire leaf burners that consumers couldn’t find in any other retail environment. When used in a home or office, the solutions saved customers space and, ultimately, time.

Many doubted the concept would work, but the home-organization pioneer has enjoyed growth at an average rate of 20 percent annually every year of its operation. Today it operates 61 stores in 20 states with a workforce of more than 6,000. In 1999, The Container Store bought elfa International, a Swedish company that was a significant supplier of shelving and storage units. In 2013, the company went public. Its commitment to culture has earned The Container Store a spot on Fortune magazine’s 100 Best Places to Work list every year since 1999.

“We do invest a lot in our people,” Shilling told me. “Our SG&A costs are in the mid-40% of sales. But our employee-first culture—having conversations, thoughtful performance reviews, caring about people, making good hiring decisions, having fun—doesn’t cost a lot of money. So I would say to organizations of all types, ages, and sizes that you can create a culture where accountability matters. You have to take the time to put things down on paper about what your goals are and what you want your culture to look like, and then make sure you execute with excellence. And if you are the CEO, have a face. Have presence as a conscious leader. Make sure that people know who you are and what you stand for and your employees will feel ownership. They will feel part of something exciting, and they will do good work for you.”

A similar commitment to finding a better way took shape one evening in 1966 when Rollin King sat with his lawyer Herb Kelleher in San Antonio’s St. Anthony Club to sketch out on a napkin a plan that would change air travel forever. Following five years of lawsuits by competitors that sought to keep Southwest Airlines grounded, the scrappy airline thwarted its competition by flying three Boeing 737s between Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio. Today, while every other major airline has declared bankruptcy over the past 30 years, Southwest Airlines has become the largest domestic carrier with the highest customer satisfaction rating and best on-time performance—all while turning a profit. It’s a $17 billion success story, and culture has played a big part in that success.

“Southwest Airlines has had a unique culture from the very beginning,” Elizabeth Bryant told me.

For Southwest, culture is not considered a training program, a technique, or strategy du jour, and that surprises even seasoned executives who join the airline. “I’ve heard a senior leader at Southwest Airlines say after joining us that she had to go through corporate detox,” says Bryant, because “to truly experience our culture feels a little bit different. Culture isn’t something that we have to make our employees do, culture is who we are. And whatever role employees are in, they take great pride in the fact that we’re connecting people to the important moments in their lives through friendly, reliable, and low-cost air travel.”

Bryant says this culture “is fully embedded into the DNA of Southwest Airlines.” Employees are involved in decision making. “When you have that type of trusting environment where we can have open dialogue that leads to a decision, by having the ability to weigh in on that decision, as an employee I am more committed to that decision and therefore I’m going to hold people accountable to it. So it’s less about a leader holding an employee accountable and more about as employees of Southwest Airlines we hold one another accountable.”

The Southwest Airlines culture reflects its underdog beginnings. “Think small and act small, and we’ll get bigger,” preached founder Kelleher. “Think big and act big, and we’ll get smaller.” Other airlines scoffed at that thinking.

They shouldn’t have. Today, one out of every four Americans has flown Southwest, and now the company is setting its sights on service beyond the 48 contiguous states.2

“Our approach is so simple,” says Southwest’s Elizabeth Bryant, “it’s hard for people to understand. There are many smart organizations with people who are able to make smart decisions, but without a culture of trust and honesty and accountability then those great ideas are going to stay on the table and not get executed.”

Southwest trusts its employees to make good decisions based on the company’s vision—“to become the world’s most loved, most flown, most profitable airline”—and values. “We have a laser focus on our values,” Bryant says, “and that means holding people accountable to the company’s values and mission and vision. Our employees know this. People typically don’t come to work at Southwest Airlines just because it’s an available job. When they understand who we are, they connect with the cause of Southwest and they strive to achieve this vision every day.”

Over the years, Southwest heard critics say that the company’s great culture was easy to achieve because the airline was so small. Wait until they grow. They’ll focus on just being smart and not all of that people stuff. Yet Southwest has stayed true to its roots, and doing so has proven successful.

“We have always understood and valued that it’s the people that make the difference for an organization,” says Bryant, “and that has been the differentiator between us and other companies.”

Big, small, or in between, success is not predicated on size.

“A lot of what we do here you wouldn’t expect to find in a large corporation,” says Tony Cortese of Herman Miller. Look on any list—Most Admired, Best Places to Work, Most Innovative—and you’ll find this pioneering company.

“What works so well for us here at Herman Miller,” Cortese told me, “is the stuff that small companies would, could, and should do: look for talented people who are energized about what you’re doing, give them latitude to express themselves and explore opportunities, be very open in your communication, establish high expectations and put systems in place to measure those expectations, talk to them frequently about performance, and then get out of the way and give them the opportunity to excel.”

That sounds like common sense, and yet those principles are not common practice in most organizations.

COMMONSENSE APPROACH

Ray Napolitan has followed a similar commonsense approach in leading three different organizations to success for Nucor: a start-up, an acquisition, and an established business.

Napolitan earned his start-up spurs when he spearheaded Nucor’s expansion into Texas with the Nucor Building Systems Division he helped start from scratch in Terrell, Texas. After eight years in Texas, Napolitan was next asked to integrate Nucor’s 2007 acquisition of American Buildings Co. into the Nucor culture. For three years, he led a team of 1,000 employees in seven locations where he helped establish the company’s safety-training culture, its pay-for-performance incentive system, and business and leadership training at all levels within the company. In 2010 he was promoted to president of the Vulcraft/Verco Group, and subsequently to his current position.

Napolitan has been part of creating cultures from the ground up and changing existing ones. Was it easier or more difficult to change a culture or create one?

“With a start-up and with an acquisition,” he told me, “we had to build a culture of accountability. We had to build trust. And we had to create vision and alignment. With a start-up, people didn’t know any differently so there were no ill feelings. We had to teach not only culture but product and technical training. We started with great folks, but there was more training involved.

“With the acquisition, we had great people but there was a big mistrust of management—and I’m using the word management and not leadership on purpose. So building trust was key.”

With the acquisition, Napolitan started with two advantages. First, despite the mistrust of management, he inherited a great team who, for the most part, fit the Nucor culture but who had never been exposed to the Nucor thought processes. Second, these people knew the metal-building industry. “There was a strategic fit to our acquisition,” says Napolitan, “and, just as important, there was cultural fit that matched our core values.”

Napolitan is playing change agent within the Vulcraft/Verco Group as well. The organization he’s leading was the first Nucor division that goes back to the 1940s, and originally was called the Nuclear Corporation of America.

“For many years in the Vulcraft division,” says Napolitan, “we really didn’t need to be very strategic. If the order book got too heavy, we turned the margin dial up. If we needed some work, we turned the margin dial down. We were—and still are—the most operationally effective company in the industry, and we had such a cost advantage over our competition.”

The Great Recession changed that approach.

“That recession,” says Napolitan, “prompted us to develop a vision that could answer the question, ‘What are we really doing here?’ We realized we had to change our culture from one that was used to ‘catching’ to a culture of ‘pitching.’ Fortunately, we have many great teammates to help us think differently and execute our strategies.” Napolitan says that start-ups, acquisitions, and established businesses each have their challenges. “I would not say that one is easier or more difficult than the other,” he says, “and each has different challenges. In each case, the key to building and maintaining a culture of accountability is great people.”

HIGH-PERFORMANCE CHARACTERISTICS

Whether you are starting a company, blending two organizations as part of a merger or acquisition, joining an existing company in a leadership position, or getting ready to amp up your organization’s performance, you’ll discover similarities that are transferrable to your organization:

1. Beliefs that form the bedrock of trust

2. A mindset and discipline to achieve excellence

3. A commonsense approach to getting things done

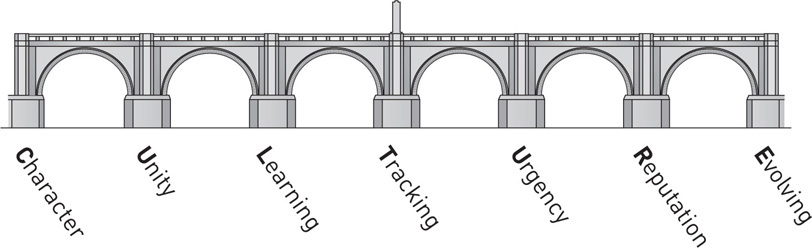

It became clear from my interviews with the leaders you will meet in this book that high-performing organizations share seven distinct characteristics that I call the Seven Pillars of Accountability.

![]() Character. An organization’s character is shaped by its values, and these values are clearly defined and communicated. The organization does what is right for its customers, employees, suppliers, and investors, even when it’s difficult to do so.

Character. An organization’s character is shaped by its values, and these values are clearly defined and communicated. The organization does what is right for its customers, employees, suppliers, and investors, even when it’s difficult to do so.

![]() Unity. Every employee understands and supports the organization’s mission, vision, values, and strategy, and knows his or her role in helping to achieve them.

Unity. Every employee understands and supports the organization’s mission, vision, values, and strategy, and knows his or her role in helping to achieve them.

![]() Learning. The organization is committed to continuous learning and invests in ongoing training and development.

Learning. The organization is committed to continuous learning and invests in ongoing training and development.

![]() Tracking. The organization has reliable, established systems to measure the things that are most important.

Tracking. The organization has reliable, established systems to measure the things that are most important.

![]() Urgency. The organization makes decisions and acts on them with a sense of purpose, commitment, and immediacy.

Urgency. The organization makes decisions and acts on them with a sense of purpose, commitment, and immediacy.

![]() Reputation. The organization rewards achievement and addresses underperformance, earning the organization and its leaders a reputation, both internally and externally, as a place where behavior matches values.

Reputation. The organization rewards achievement and addresses underperformance, earning the organization and its leaders a reputation, both internally and externally, as a place where behavior matches values.

![]() Evolving. The organization continuously adapts and changes the organization’s practices to grow its marketplace leadership position.

Evolving. The organization continuously adapts and changes the organization’s practices to grow its marketplace leadership position.

You probably noticed an acronym: C.U.L.T.U.R.E. It’s deliberate and will help you remember the seven pillars.

This acronym also will help you remember that your culture is a significant predictor of your future performance.

As I thought about the challenge of getting from Point A to Point B, I recalled my experience in Provence and imagined a bridge spanning an abyss supported not by a single arch like the one at Pont d’Artuby but instead by seven pillars, each representing one of the seven characteristics that are essential in high-performing cultures:

The Seven Pillars of Accountability

Crossing the abyss—moving your organization from Point A to Point B—requires the commitment of you and your team.

Many of your teammates are ready for the journey. Others are not: They may be unsure of the destination, they may believe there’s a better way to make the journey, or they may be scared of where you’re asking them to go.

The leaders you will meet and the lessons you will learn will help you create a culture where accountability drives performance and helps you cross the abyss and reach your destination.