8

INSTILLING A SENSE OF URGENCY

Urgency

Rise early. Work hard. Strike oil.

—J. Paul Getty

When J. Paul Getty died in 1976, he was worth more than $2 billion and one of the richest men in the world.

Ever the overachiever, Getty reminded a reporter that “a billion dollars isn’t worth what it used to be.”1

Getty earned his wealth in the oil business as a shrewd, hard-working man who spoke four languages fluently, was conversational in four others, and could read Latin and ancient Greek. His collection of essays on success became his book, How to Be Rich. In it, he wrote that he believed most executives were “dedicated to serving the complex rituals of memorandum and buck-passing.”2 In contrast, Getty had incredibly high expectations, starting with himself, and he held himself accountable to the urgent pursuit and achievement of his goals. There’s no evidence Getty ever met Clint Murchison, Sr., another member of the elite oil wildcatters club, but both men hijacked, paraphrased, and then regularly used as though it was theirs a quote about money that seventeenth-century philosopher Francis Bacon first expressed as “money is like muck, not good unless spread.”

Murchison changed “muck” to “manure” and added that “if you pile it up in one place, it stinks like hell.”

In 1944, Clint Murchison had piled up an investment in new houses that was starting to stink like hell. He had ventured into real estate by purchasing land and building houses made mostly from products his collection of companies produced. The houses were reasonably priced, well designed, and well built. But they weren’t selling. Murchison was growing impatient.

He had admired from a distance a spunky young hat shop owner whose best customer was Murchison’s wife, Virginia. “The next time you visit your friend who sells the crazy hats,” Clint suggested to Virginia, “ask her if she has any ideas how to sell my crazy houses.”3

Virginia Murchison picked up her hat-shop friend Ebby Halliday, and they drove over to look at Clint’s houses. Three weeks later, Ebby had secured her real estate license, sold all three of Murchison’s houses, sold her thriving hat business to her partner, and started a new business.

Today, Dallas-based Ebby Halliday, REALTORS is the largest independently owned residential real estate company in Texas and ranks twelfth in the United States with approximately 1,500 sales associates and staff in 25 offices. In 2012, the company participated in almost 16,000 property transactions with a sales volume of approximately $4.8 billion. The firm’s website, ebby.com, averages more than 16,000 visits daily.4

THE FIRST LADY OF REAL ESTATE

Everyone calls her Ebby, and in residential real estate circles, everyone knows who you’re talking about. Ebby Halliday is the first lady of real estate.

Her business grew year after year, and she became an outspoken advocate for business and for women. Ebby was invited to the White House in 1975 to share her views on business, and was named by Realtor Magazine one of the 25 most influential people in the industry. She has served the city of Dallas in a variety of leadership positions in and out of real estate, and, from her first days in business, has traveled the globe in a tightly packed speaking schedule as an indefatigable cheerleader for Dallas and as a savvy business-woman spreading the word that successful businesses are built by serving your customer, serving your community, and serving your industry. Ebby received the prestigious Horatio Alger Award for her “remarkable achievements accomplished through honesty, hard work, self-reliance, and perseverance over adversity.”5

I first met Ebby Halliday when I invited her to speak at a breakfast for executives whose companies had recently joined the ranks of the Dallas 100, the top fastest-growing companies in Dallas.

She had just turned 91, but hadn’t slowed down. She had plenty of energy, generosity, and great advice for leaders looking to grow themselves and their business. I watched these leaders—successful in their own right—as they took notes to capture Ebby Halliday’s life lessons, her perspective on a range of issues, and her wisdom.

Ebby’s path of upward trajectory is the story of guts, urgency, and knowing what makes people tick.

A LEGACY OF FIRSTS

Like other successful leaders I spoke with, Ebby Halliday has rock-solid values, uncanny instincts, and an incredible work ethic. She worked after hours and weekends during her high school years in Abilene, Kansas, selling hats in the basement of a department store “at a time people could barely afford to eat,” she told me. “When you develop an ethic where if you don’t work, you don’t eat, you have a leg up on anything else that happens in your life.”

She graduated in 1929, the year every bank in America closed. “The Great Depression was in full swing with bread lines around the corner,” she says, “but I kept moving.” Ebby moved to Dallas and began selling hats at W. A. Green Department Store across from Neiman Marcus. In seven years, she had accumulated $1,000—“quite a sum in those days”—and, during an appointment to have her tonsils removed, asked her doctor for advice on speculating in the stock market. “I told him I wanted to become an entrepreneur,” she remembers. “He suggested cotton futures, and cotton was king in Texas, so that’s where I invested my money.”

Ebby’s gutsy decision to invest her entire net worth of $1,000 became $12,000 in three months, and she opened her own hat shop. Months later she had sold Clint Murchison’s houses and launched a pioneering career in residential real estate. By the time of Ebby’s 1965 marriage to Maurice Acers, a former FBI agent and lawyer, she had assembled an impressive list of industry-changing innovations that she either created or popularized.

When Ebby and I met for our final interview, she recalled with a sense of accomplishment and gratitude the results of her life’s work. She and Michael Poss tell her inspiring story in Ebby Halliday: The First Lady of Real Estate, and here are just a handful of her notable achievements:

![]() Created the first display homes. Clint Murchison’s houses may have been sturdy, but “they were ugly,” Ebby told me. “So I decorated them and they became the first display homes. And I sold them.”

Created the first display homes. Clint Murchison’s houses may have been sturdy, but “they were ugly,” Ebby told me. “So I decorated them and they became the first display homes. And I sold them.”

![]() Leveraged MLS information. Dallas was slow to adopt Multiple Listing Service; Ebby was the city’s first broker to complete a transaction in 1953.6

Leveraged MLS information. Dallas was slow to adopt Multiple Listing Service; Ebby was the city’s first broker to complete a transaction in 1953.6

![]() Championed women’s causes. In 1955, Ebby formed the Dallas chapter of the National Association of Real Estate Boards (NAREB) Women’s Council at a time when those boards consisted almost entirely of men; two years later she was elected president of the national council.7 A familiar theme in her speeches was, “Know your business … ask no special favors, and act like a lady but do business like a man.”8

Championed women’s causes. In 1955, Ebby formed the Dallas chapter of the National Association of Real Estate Boards (NAREB) Women’s Council at a time when those boards consisted almost entirely of men; two years later she was elected president of the national council.7 A familiar theme in her speeches was, “Know your business … ask no special favors, and act like a lady but do business like a man.”8

![]() Created the first national referral service. Established a network in 1960 enabling brokers to buy, sell, and inventory houses coast-to-coast.9

Created the first national referral service. Established a network in 1960 enabling brokers to buy, sell, and inventory houses coast-to-coast.9

![]() Led the way among realtors to harness technology. In 1970, she put technology to use in order to share up-to-the minute information about home listings.10

Led the way among realtors to harness technology. In 1970, she put technology to use in order to share up-to-the minute information about home listings.10

![]() Established three separate companies to handle leasing, mortgages, and titles. Using this portfolio approach provided the company with alternative revenue streams that insulated it from market swings.11

Established three separate companies to handle leasing, mortgages, and titles. Using this portfolio approach provided the company with alternative revenue streams that insulated it from market swings.11

![]() Created an in-house resource: Ebby Ink. This outlet allowed her to write, publish, and print sales and home listing literature for her sales associates.12

Created an in-house resource: Ebby Ink. This outlet allowed her to write, publish, and print sales and home listing literature for her sales associates.12

![]() Established a corporate relocation program. This program played an important role in helping big companies like Dresser Industries, Associates Corporation of North America, Lennox Industries, Celanese Chemical, American Airlines, and Diamond Shamrock relocate their headquarters.13

Established a corporate relocation program. This program played an important role in helping big companies like Dresser Industries, Associates Corporation of North America, Lennox Industries, Celanese Chemical, American Airlines, and Diamond Shamrock relocate their headquarters.13

Ebby Halliday has been a keen observer of the world around her. She brought fresh, creative approaches and took calculated risks to keep her company moving forward. But great ideas are worthless without practical application and relentless execution, and Ebby held herself and those around her accountable to make things happen. By whatever name you choose to call it—persistence or passion, stubbornness or stamina, drive or determination—Ebby Halliday, like all great leaders, demonstrates an urgent will to win.

TURNING KNOWLEDGE INTO PERFORMANCE

The ability to pause and reflect on organizational and individual learning is perhaps the single greatest talent of exceptional leaders. As the leader, you don’t have to be the one solving the problems, but you must identify them and then act on them.

Balancing reflection with action is one of the hallmarks of a great leader. Thinking things through can make a good plan better. Effective execution of a good plan can make your company great. Retailers remind us that their sale events are “For a limited time only” for a reason: Great opportunities don’t last forever.

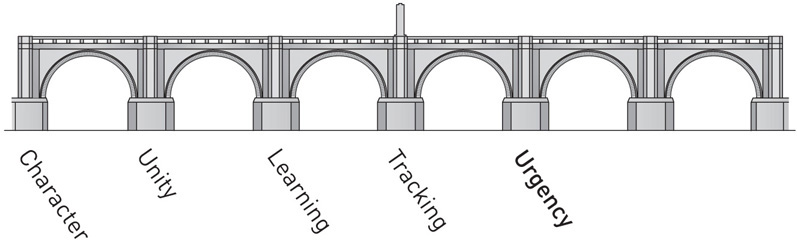

Just as the Unity Pillar and Tracking Pillar are linked by virtue of what each communicates about expectations and progress against those expectations, the Learning Pillar, Urgency Pillar, and Evolving Pillar are linked because the characteristics shared by these three pillars embody the approach exceptional companies take to harness, apply, and benefit from knowledge.

The Urgency Pillar converts learning into high performance by:

![]() Sustaining a laser-like focus on improving processes to drive productivity

Sustaining a laser-like focus on improving processes to drive productivity

![]() Minimizing red tape to create a sense of urgency and a bias for action

Minimizing red tape to create a sense of urgency and a bias for action

![]() Recognizing mistakes and moving quickly to address problems

Recognizing mistakes and moving quickly to address problems

Large companies and small businesses alike recognize the impact produced by a sense of urgency in the workplace.

Among the executives completing the accountability assessment, 76 percent “strongly agreed” or “agreed” that decisions are acted on “in a timely manner,” and 79 percent “strongly agreed” or “agreed” that “we recognize our mistakes and move quickly to address problems.”

Minimizing red tape was a factor in driving performance among 61 percent of the executives, and making “decisions with less than 100 percent of the data” was “strongly agreed” and “agreed” to by 57 percent of the executives.

Ray Napolitan of Nucor characterizes this type of decision making as a “commonsense approach” to leading people and projects. “We’ll go down a path and we will think through how best to approach a particular problem or opportunity,” he says. “We’ll get 60–70 percent of the analytical part that we’ll mix with a gut feel for whether something will be successful, and then make a decision to implement our decision, understanding that we’re going to make adjustments based on a commonsense approach. So if something doesn’t work, we change it. We’ll move quickly to tweak things. We don’t get caught up in paralysis by analysis.”

GREAT RESULTS COME STEP BY STEP

Ebby Halliday’s successful career and her company’s upward trajectory have been bracketed on the front end by the Great Depression of 1929 and the Great Recession of 2008–2009, with 10 recessions in between.

“We’ve been up and down in our six decades of business,” Ebby says, “but we’ve been resilient, we’ve built our reserves, and we keep progressing, even when the market is dipping, so we’re prepared for the end of a downturn.”

The decade of the 1960s, for example, started and ended with a recession, and while these two recessions didn’t slow sales for Ebby and her growing team, they stretched cash. During that decade, Ebby said she once paid out “every cent” she saved to her employees. She credits her longtime CFO Ron Burgert with “keeping us solvent,” though Ebby was the force behind those character-building decisions, and her disciplined focus on serving customers helped her small, growing company overcome disaster. By 1971, Ebby Halliday Realtors had achieved its twenty-sixth consecutive year of sales increases.14

Ebby Halliday loves football, and she compares business to her favorite sport. “You want to play in the Super Bowl,” she told me, “but first things first. When you’re down, you can’t always try to score a touchdown. You have to make a first down. Then another one, and another one, and another one. Make enough first downs, you’ll eventually score your touchdown. Make enough touchdowns, you win the game. Win enough games, you play in the Super Bowl. There’s a lot of blocking and tackling in between. It’s not all glamorous. The important thing is to not give up.”

Leaders at exceptional companies initially were interviewed during the depths of the worst global recession in 80 years. Follow-up interviews were conducted as the economy recovered. In the five years between recession and recovery, all of these companies changed their practices but none of them changed their principles, and none of these companies permanently eliminated any jobs other than for individual performance issues. How did they do it?

They doubled down on serving their customers, made tough decisions, and then acted with a sense of urgency to implement them.

Don’t confuse urgency with lots of change. People can handle only so much change because it’s stressful. And don’t equate urgency with rash, hasty decision making and execution. Urgency for these high-performing companies is the disciplined focus on a handful of compelling priorities that are executed with purpose, commitment, and immediacy.

GOOD PERFORMANCE IN BAD TIMES

“We certainly share the long-term vision with our people,” says Herman Miller’s Tony Cortese, “and there’s a matter of flexibility and practicality also. We talk frequently about where we’re at now. Former Herman Miller CEO Max De Pree was famous for saying, ‘One of the biggest responsibilities for a leader is to tell their people what time it is.’ And that means getting out there on a regular basis and saying, ‘Here’s where we are.’ So every month all the employees are exposed to where we are with respect to our annual goals. Where we are with respect to large contracts or issues that we’re contending with.”

Even in the best companies problems arise. When that happens at Herman Miller, leaders take immediate action. That may mean that a plant manager calls his people together to discuss and resolve an issue in real time. “We recognize that we’ve got to get the word out and we have to talk to people on a regular basis,” says Cortese, “and that can mean morning huddles with work teams to say, ‘Here’s what we’ve got today. And we’ve got to get this delivered by Monday, and that means that we’re going to work this weekend and here’s what we need to do.’ It’s our belief that if the employees don’t understand what it is that we’re asking of them, then we can’t expect them to deliver the results we need. So we overcommunicate.”

Smart people crave communication, and smart companies deliver. Yet there’s always room for improvement.

“It’s an exhaustive process,” says Cortese, “and there are times when it’s much easier to say, ‘Yeah, we’ve told them that, now let’s turn our attention to something else.’ You can’t do that. You have to be ever-diligent with communication. That’s probably one of our biggest takeaways over the years at Herman Miller: we over-communicate, and that’s one of the things that makes us different from other companies.”

Each executive I interviewed made it clear that every person—from the CEO to the hourly worker—was sharing the financial and emotional pain of the tough measures prompted by the recession. The decisive action taken by the leaders of these exceptional companies saw their companies emerge from the recession stronger than ever.

URGENCY IS A COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE

As the recession worsened, urgency became a competitive advantage for well-run companies.

At The Container Store, the continuing sales decline brought what Casey Shilling calls “a laser-like focus on expense management.” The solution was obvious, but in a company where “one great employee equals three good employees,” the execution was painful. The company cut some employee benefits to prevent layoffs.

In good times, exceptional companies build trust. In tough times, trust is tested.

The Container Store was performing better than other retailers, but the recession hit the company, so executives moved quickly to bring expenses in line. “Our biggest financial commitment, as it is in most organizations,” says Shilling, “is in our investment in people. So we initiated a salary freeze and stopped our 401(k) match. Those are yucky conversations to communicate to 6,000 employees. But our people overwhelmingly supported those decisions because of the culture we’ve created over the last 35 years.”

Emerging from the recession, The Container Store increased its head count to 6,000 employees from 4,000 in 2008, and in 2012 alone opened stores in five new markets in California, Florida, and Virginia, recorded revenues of $707.5 million and expects to join the billion-dollar club in a few short years. Not bad for a company that started in a 1,600-square-foot warehouse.

While the Great Recession of 2008–2009 touched virtually every business on the planet, some industries were hit harder than others. Fortune magazine called 2008 “a historic year of red ink,” and listed airlines and hotels “among the worst hit.”15

Southwest Airlines reported 2008 revenues of $11.023 billion and, though its profits were off 72 percent from the previous year, Southwest was the only major airline to make money and continue its run of what has become 40 consecutive years of turning a profit.16 The following year was even worse for airlines, and Southwest’s revenues dropped to $10.35 billion, yet the company still earned a profit.17 Despite punishing market conditions, Southwest continued to execute its vision of becoming the “World’s Most Loved, Most Flown, Most Profitable Airline,” and it closed on its acquisition of AirTran in 2011 while other companies were closing their doors.

People weren’t traveling, so they weren’t booking hotel rooms. In the spring of 2009, things weren’t too sunny when Marriott International reported a 29 percent decline in operations from the previous year. “Despite the downturn,” said CEO J. W. Marriott, Jr., “we’re moving ahead,” and he confirmed the company was maintaining its urgency on a range of initiatives to stay “on track to open over 30,000 rooms in 2009.”18

As Southwest Airlines and Marriott navigated the recession’s stormy seas, Nucor was on its way to achieving revenues of $23.66 billion, $1.83 billion in net earnings, and producing 25.18 million tons of steel. But hard times were just around the corner for America’s biggest steel producer.

The pay-for-performance compensation model Nucor’s Ray Napolitan describes in Chapter 5 was established in the mid-1980s, so it had been battle-tested during a 30-year span that included domestic recessions and international currency manipulations that created an unlevel playing field for U.S. manufacturers.

When the bottom fell out in 2009, Nucor was ready, but that didn’t make the decisions any easier or any more palatable.

COURAGE IN TOUGH TIMES

Nucor’s sales plummeted to $11.19 billion, a decline of 53 percent. Nucor suffered a $293 million loss and produced 17.57 million tons of steel. All Nucor employees, including those at the top, earned less money, yet the company did not lay off a single employee due to lack of work.19

“As expected,” Nucor CEO Dan Damico told his shareholders, “2009 proved to be the most challenging year we have ever faced. The recession severely deepened in late 2008, significantly reducing demand for our products, particularly in the first half of the year. The past 18 months have been a time of hardship and difficulty for all 20,400 on our team.”20

“It’s easy to be courageous in the good times,” says Nucor’s Ray Napolitan. “It’s very difficult to have courage and commitment when times are tough.” Yes, Nucor employees made less money during the Great Recession, but the company’s 40-year no-layoff practice continued. “Our goal during difficult times,” says Napolitan, “is to train our folks, develop techniques, improve our processes, and get ready so that we will emerge stronger when the market turns.”

Nucor was ready for the downturn, and its leaders and workforce were well positioned to lead the recovery in manufacturing. In 2010, Nucor’s steel production rose, and rose again in 2011, and again in 2012, when the company recorded 23.09 million tons of steel.21

“We bring a sense of urgency to our daily work,” says Napolitan, “but Nucor has always focused on the longer-term view. We’re all about continual improvement and long-term thinking, and that’s what separates us from our competitors.”

COMMUNICATING URGENCY

During the Great Recession, air travel and hotel bookings were down, steel production was down, and commercial construction was down.

In Edmonton, Alberta, in Canada, Clark Builders began feeling the recession about a year behind the United States.

Founded in 1974, Clark Builders had grown to $473 million by 2008, and gained a reputation for delivering great results in cold climate construction.

Brian Lacey joined the company in 1990, and today he’s one of Clark’s eight partners. He spent his first eight years at Clark working 12- to 14-hour days seven days a week at remote locations, first in the Canadian high arctic and later in Siberia.

He was 23 years old when he received his first remote posting, and he admits that he “didn’t have a lot of formal management training; it was pretty much trial by fire.” Working in brutally cold temperatures, Lacey learned a lot about himself, about what it takes to keep a project on schedule and on budget, and about accountability.

“Accountability is a trait,” he told me, “and it’s critical to achieving large-scale success, which is typically achieved as a sum of small successes.

“What I’ve found is that people tend to want to do well, and I’ve learned that communication is key to helping them succeed. Like any process, communication can have a weak link, and when that weak link breaks the chain in your critical path you can find yourself in trouble.”

Lacey identifies his top performers to handle the critical items on a project. He creates a sense of urgency, charges them with the responsibility for the outcome, and sets the up-front contract so expectations for accountability are clear.

“When you provide good people enough information to operate well, they’re going to strive to meet or exceed your requirements,” Lacey says.

“If a project team comes back at the end of a job and a manager says, ‘They weren’t very successful on their production, and our productivities are on the line,’ the first questions to the manager are ‘Did you advise them of the metrics? Were they aware of our production goals?’ And more often than not I find the necessary information wasn’t communicated, it wasn’t measured, and it wasn’t managed.

“I often use this analogy: If you ask somebody to go for a run and when he comes back you say, ‘I wasn’t very happy with your performance,’ but you haven’t told him if he’s doing the 100-yard dash or a 26-mile marathon, then you’re really not being true to him out of the gate.”

“SAY, STAY, AND STRIVE”

In 2009, Clark grew to $537 million, and then, says Lacey, “the wheels fell off the economy so we dropped to $506 million.” The company has reinstalled the wheels and is cruising toward revenues of $650 million.

Despite the challenging market fluctuations, the team at Clark has achieved consistent growth in employee engagement among its 900 employees who operate out of four offices in the three Canadian provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Northwest Territories.

For five consecutive years, including during the challenging economic downturn, Clark Builders has been named one of the top 50 employers in Canada. “A small number of companies have achieved this distinction two or three times in consecutive years,” says Lacey, “but earning the distinction five straight years is a rare accomplishment.”

Clark is benchmarked against other Canadian companies as well as other construction companies by Aon Hewitt, the international human resources and consulting firm. Among all participating construction companies, only Clark drove the survey down to its field staff. “Where I come from,” says Lacey, “it’s pretty easy to create a good work environment. When it’s hot outside you’ve got your air-conditioned office, and when it’s cold outside you’ve got the heat turned on. But when you’re driving your culture down to the guys who are getting mud on their boots and are struggling through everything from rain to sleet and snow and we have those levels of engagement, that’s pretty gratifying.”

The Aon Hewitt study measures three metrics: “Say, stay, strive.” What do your employees “say” about the company to colleagues or friends or others? What’s the likelihood they will “stay” with the company for the long term relative to market competitiveness? And what’s the likelihood they will “strive” to go above expectations?

Lacey is responsible for all field construction, everything that happens outside of the office, which involves 700 workers. “Any rating above 80 percent is considered high engagement,” says Lacey, “so I was pretty happy that our team achieved a 97 percent engagement rating.”

Clark Builders has created a culture by design, not by default. The company is intentional about its culture, and the employees know it and appreciate it. Only 3 percent of Clark’s employees were considered “passive” and none of the employees were considered “disengaged,” an extraordinary achievement compared with other studies that indicate 30–50 percent of the workforce of many organizations are disengaged. The overall engagement for Clark Builders in 2009 was 74 percent; in 2010, it was 76 percent; in 2011, it was 78 percent; and in 2012, it was 80 percent, earning Clark Builders the distinction of being ranked the thirty-second best place in all of Canada to work.22 Lacey told me “the average 2013 score in North America was 63 percent, the average score in Canada was 79 percent, and the average for construction and engineering was 74 percent.” In 2013, Clark posted its fifth consecutive year of being named to the list of the 50 best employers in Canada, achieving a new level of employee engagement of 81 percent.

ACTING ON THE DATA

When achievement of any kind is recognized, some people will celebrate, sit back, and think, “We’ve arrived.” Others will celebrate and then get back to work.

“I think there are a lot of companies that are named to the 50 Best list that probably get the report and they’re pretty darned proud about being named, and they consider that they’ve arrived,” says Lacey. “We celebrated, of course. And then we analyzed the data. We found areas that we could improve upon, starting with the low-hanging fruit. What were the areas across the business where people had the most concerns?”

Lacey and his team categorized the issues, then he went into the field to visit with employees in groups of 10 people, asking for feedback on the report. They listened, made changes based on the feedback, and then communicated the changes to the employees.

One consistent piece of feedback was the desire for communication about the day-to-day business from a management perspective. So every quarter Clark holds a town hall meeting, shutting down job sites at 3:00 p.m. so that employees can attend and get an overview of the business.

MEDIOCRITY IS NOT ACCEPTABLE

The Merit Contractors Association in the Canadian province of Alberta is comprised of approximately 1,400 contractor member firms that employ more than 45,000 people in commercial, institutional, and industrial construction sectors.

The association bestowed on Clark Builders the Willard Patrick Training Award as the top firm in Alberta for training its employees. Clark Builders’ investment in training and development is a direct result of its first engagement study.

“We’ve got a pretty intensive training opportunity for our people,” says Lacey, and Clark’s training curriculum includes a career development path.

“I created a graphic with a guy I call ‘New Boots’ who’s never been on a project before, and he shows up in those brand-new boots.” Lacey charts various career paths from bottom to top. “We track and manage their development,” says Lacey, “and we make it clear that not everybody is going to get there. And not everybody aspires for that, so if you’re happy at a particular level, by all means stay there. We communicate that we’ll provide the opportunities. What they do with that opportunity is completely up to them.

“People appreciate that we’re giving them the opportunity to be successful, and they appreciate that we recognize their hard work. They know we’re not going to settle for mediocrity.”

The moment I stepped into Lacey’s Edmonton office it was apparent he loves golf. Lacey equates Clark’s results and desire for continuous improvement to a golf score. “If you’re shooting 130,” says Lacey, “it doesn’t take much effort to get down to 120. That score is like our first year of the study. There was low-hanging fruit. But if you’re consistently shooting 80, it’s pretty tough to get to 75. So as we continue going through this process, we’re really dialing in to the details. We understand that our challenge is going to be sustaining our high performance. There’s not that much room to improve. It’s all in the details.”

As it always seems to be for the best leaders at the best companies.

THE NEED FOR SPEED

“We sell celebration,” says Bob Hendrickson of RNDC, the world’s thirteenth largest distributor of fine wine and spirits.

But 2009 didn’t offer a lot to celebrate, nor were people buying much fine wine and spirits in a down economy, so RNDC’s upward trajectory of year-over-year growth declined. The following year RNDC rebounded with double-digit growth, and one reason was the sense of urgency that Hendrickson created inside the organization. It was urgency, Hendrickson recalls, that his board of directors noticed because of the speed in which he dealt with underperforming managers.

RNDC, as noted in Chapter 6, hires and promotes hundreds of people every year.

When Hendrickson was promoted into his current position, he became responsible for RNDC’s eastern half of the United States, picking up 12 new states. In three years, Hendrickson upgraded and promoted talent at the most senior levels of the company.

“We’re continually upgrading our talent,” says Hendrickson, “and we’re able to do that—even in top-flight jobs, which is hard to do—because our bench is deep enough to allow us to make those kinds of moves internally. It’s important that we have internal growth, and I believe it’s important that we look outside the company with every fifth or sixth hire so that we can get some fresh blood and different thinking. So I believe it’s healthy to promote from within, and we do plenty of that, and I believe it’s just as healthy to bring in people from the outside every so often to continue to mix up the gene pool.”

PERSISTENCE PAYS

People can purchase most anything they want these days from more than one source. If you don’t like the brands of fine wines and spirits RNDC is selling, you likely can buy the same sort of product from another supplier elsewhere. So while Bob Hendrickson says RNDC “sells celebration,” he’s also selling accountability. His customers depend on RNDC to deliver what they promise.

When it comes to getting a sense of who’s performing and who’s not, “I’m a little bit old-school,” says Hendrickson, a youthful 53. Yes, he receives and analyzes plenty of reports, but nothing beats face time.

Hendrickson hops on a flight as soon as he’s given new territories and he works with the mid-level managers for two or three days before meeting the state president. “I’m on the road every week and out of the office about 70 percent of the time,” he says. “When you get those mid-level managers in a car and you’re going around to different accounts, they are apt to tell you a lot more about the truth of what’s going on—good or bad—than a guy who’s looking at it from 30,000 feet.

“In just about every case, these mid-level guys know who I am. But they open up because I spend a lot of time talking to them, being persistent about the marketplace, our associates, and what engages them. I am genuinely interested in them. I want them to understand that I used to have their job. I’m no different than them. I want to help them succeed, and I want to make the organization better. And you can sense when people are holding back. So my persistent approach ultimately pays off, and eventually they open up and provide insights that help me understand how to define success with them.”

Hendrickson judges a person’s ability to run a high-performing unit by how their people are being developed. He examines a manager’s skill set, how they manage in the market, manage their business, and manage their bottom line. He also factors in extenuating circumstances when a manager is losing money because of market conditions.

“For the most part,” says Hendrickson, “I think you can sense a manager through his leadership ability, how people view him, and how he carries himself around his organization.

“I’m a big believer in telling a person what your expectation is. If they don’t understand how to do it, train them how to do it. And if they can’t do it, you need to make the decision about whether they’re a good fit for RNDC.”

RNDC’s state presidents are tenured leaders, so training is rarely the issue. “The state presidents who have been replaced,” says Hendrickson, “have years of experience in the job. When I sense that an experienced manager is not successful and I have given them due warning and told them what the expectation is and they have not met that expectation, they need to pursue their career elsewhere.”

The idea of holding long-time employees to the same high standards as the rest of the organization has not always been comfortable for the board, even when it’s clear performance is not measuring up and the underperformers have been given months to improve.

“I move quicker than the board might like me to move,” says Hendrickson, “because they view things in the context of a personal relationship. But because I’m being held accountable by the board to deliver the numbers, this is where the discussion ends. I say, ‘If you hold me accountable for running the field organization, for the revenues, and for the bottom line, then you need to let me put the right team on the field.’ The board has deferred to that approach in most instances.”

Terminating employees—especially those with long ties to the organization—is never easy. But leaders must address under-performing employees regardless of their level and tenure in the organization, and sometimes that means terminating people you helped hire, employees who have become friends, and even relatives.

A CEO once reported to his peers in one of my Vistage groups that he had terminated an executive who also was a family friend after giving this person every chance to succeed. Hearing this news, a fellow CEO remarked, “Congratulations on your business successes and condolences for the tough personnel decision. I am afraid it comes with the territory.”

When was the last time you dove down two or three levels into your organization to find out what’s really going on? Is there any bad news you’re pretending not to know? Are you bringing a sense of urgency to your decision making?

When truth can be spoken to those in power without fear of retribution, then listening to those around you will tell you what you need to hear. How you act on this information defines your culture and drives your performance.

FACTS AND TRUTH CAN DIFFER

Ken Polk and Fran McCann didn’t start Polk Mechanical Company from the ground up.

They bought a company out of bankruptcy in 2003, inheriting $50 million in contracts, 1,000 employees, and hundreds of jobs that needed to be completed.

They had two immediate challenges: First, they had to downsize quickly because the business wasn’t sustainable at that size; second, while making this transition, they had to figure out what kind of company Polk Mechanical was going to become.

The situation appeared grim: The economy was bad. Polk Mechanical was a start-up company working out of the same office, with the same people, working in the same markets, for the same customers, doing the same kind of work as the prior bankrupt entity.

Looking at the facts, a person could argue, “This isn’t a new business. It’s an old business with all the stuff that didn’t work the first time. What makes you think it’s going to work the second time?”

McCann believes truth is different from facts. “Those might be the facts,” says McCann, “but the truth is those facts didn’t dictate our future. We were going to build a different kind of business.”

They quickly went to work restructuring the business to look the way they wanted it to look. This team believed that the clearer the picture you have of what you want, the greater the chance you’ll find what you’re looking for, so they challenged themselves to have absolute clarity about what they wanted and then to look for the good in every situation. Ken Polk and Fran McCann offloaded offices, lines of business, and projects that weren’t a core part of their service to their best customers, weren’t generating positive results, or were too small and not scalable. They also terminated underperformers.

Putting more things on their “stop doing” list kept them focused. “It’s counterintuitive,” says McCann, “that the more tightly focused in on what a target customer or target project looked like, the more we narrowed our definition of success, the more the opportunities expanded.”

In five years, that focused approach helped Polk Mechanical achieve record revenues and profits. “We thought we were pretty invincible,” says McCann. “I remember preparing our 2009 budget, planning the next five years. And each year was showing growth above our prior record year. Then 2009 hit, and that was the start of the recession for us. We went from ‘invincible’ to flying so close to the trees on our banking covenants that we were concerned about overall performance.”

The firm had reliable indicators warning of the downturn, but management wasn’t connecting the dots of the subtle changes happening right in front of them. “The good news,” says McCann, “is we had the right tools. The bad news is we weren’t interpreting the tools correctly. We know how to interpret them now.”

McCann and his team had never been through anything like the Great Recession but says, “That experience strengthened our character muscles, because you do get tested in the tough times. That’s where you get to see what you’re really made of.”

McCann and his team passed the test, leading Polk Mechanical through its toughest year to performance that exceeded its prerecession record-setting year. He did it by reshaping his company’s culture.

RESHAPING POLK’S CULTURE

What should a company look and act like?

That was the question Fran McCann had to answer. “At Polk,” says McCann, “we work hard to make sure our culture doesn’t feel so bureaucratic. I don’t want to map out every step an employee can and can’t take because that limits what we’re here to accomplish in terms of delivering service to our customers.”

This philosophy is in stark contrast to the culture McCann inherited. The predecessor company had banners on the walls saying, “We are the provider of choice, the employer of choice, and we deliver great customer service.” However, its culture said otherwise: internal processes were so restrictive and cumbersome that delivering service to customers required multiple approvals; if a customer called with an emergency, by the time the required approvals were secured the customer had hired a competing firm. The old company trained employees not to think but instead to follow blindly “the rules,” even if the rules were not appropriate for the situation.

“At Polk,” says McCann, “we expect our employees to deliver exceptional customer service consistently. As leaders, we must do our job: removing, not creating, obstacles that could impede our team’s ability to deliver that service. We are confident that if we hire the right people, we don’t need bureaucracy to cause them to make the right decisions about how to do what’s right for our customers and our company.

“Part of building a company culture that feels less like a corporation and more like a community is a by-product of growing up in a big family,” says McCann. As one of seven kids with 31 people in his extended family, he recognizes and appreciates that with a large family comes great diversity in opinions and beliefs, whether about raising kids or politics or sports. Despite those differences, their family was raised with an underlying set of strong core values.

“A business is really no different,” says McCann. “If we look at our employees as part of our extended family, we will appreciate the benefit of differing opinions and approaches as long as we are all rooted in a common set of values. This family feel will cause us to be a stronger company because as we get better at caring for each other, we will get better at caring for our customers and that will ultimately show up on the bottom line.”

RESCUE IS ROBBERY

During the recession, Polk’s employees depended on the leaders to make decisions and give answers. Effective leaders turn that paradigm on its head. You don’t need to have all the answers, but you better be asking the right questions. And then you need to get your people thinking for themselves.

Polk’s leaders recognized they had done a great job training their employees not to think. The more leaders jumped in to “save the day,” the more they trained employees to check their brains at the door.

McCann concluded that rushing to rescue a colleague from failing limits that person’s independent problem-solving ability and hijacks the ability to perform at a higher level. Making all the decisions also created bottlenecks. So many things needed to get done that Polk’s leaders depended on their employees to be in the middle of things, thinking for themselves.

Although the leadership team wasn’t always comfortable letting go of the reins, the leaders trusted that doing so would reverse the course and give employees permission to think—and if necessary, occasionally fail. It was a big shift, and a move that produced more hits than errors.

ACCOUNTABILITY IS AFFECTION, NOT PUNISHMENT

For Polk, safety is the number one priority. As a result of a worsening safety record, the company instituted a compliance-driven safety culture based on zero-tolerance protocols: “Break the rules and face disciplinary action or termination.”

The company required a sense of urgency around these safety issues, and yet the harder they tried to enforce those protocols and the more disciplinary measures that were instituted, the worse their safety results got. After about a year with no improvement in results, the leaders recognized that punishing people doesn’t help them learn what they’re doing wrong, and it darn sure doesn’t help them to do it better. In fact, it puts them on the defensive. Polk brought in a new safety leader and under his direction the company converted its enforcement mentality to a “Coaches, not Cops” approach to safety.

“There is no better way to show our employees that we care about them,” says McCann, “than to have a robust safety program that ensures they go home every day the same way they came to work.”

Under the new direction, instead of writing up an employee for an unsafe act—like standing on the top rung of a ladder, which didn’t help the worker understand the risks associated with being on the top rung of the ladder—the company shifted to a coaching mode. Supervisors would call a worker down from the ladder and ask, “Are you aware of the risks associated with being on the top rung of the ladder?” And the worker would say, “Yeah, I could fall.” Then the supervisor would ask, “So if you were to fall from a 10-foot ladder and hit the concrete, what do you think would happen to you?” And the worker would answer, “I could get a concussion, I could break a leg, I could snap my neck.” And the supervisor would say, “That’s not what we want. What do you think you could do to prevent yourself from falling?” and walk employees through that process. The employees understood what Polk was trying to accomplish and saw that the company really cared about their safety; as a result, the employees took ownership in the process.

Polk instituted a program called “Is it safe? Make it safe.” It’s simple and effective. Workers ask themselves, “Is what I’m about to do safe, and, if not, what do I have to do to make it safe?” The blame game shifted to an educational dialogue. “Now,” says McCann, “it’s not about filling file folders with written warnings. That doesn’t do us any good. Over time, as our guys realized that we meant what we said and they saw us being coaches, that approach created an environment where it’s okay to tell on yourself.”

Polk also took a fresh look at its safety indicators. Most companies track the incident and the incident rate. But once an employee is injured there’s nothing the company can do to get him uninjured. McCann concluded that they had to get ahead of the incident if they were going to make a real impact on safety and the incident rate.

The company determined the leading safety indicator that could prevent injuries: near misses. If an accident almost happened, employees would complete a “Near Miss” form and report it. Leaders studied the causes, visited job sites, and shared their observations as part of the company’s “Toolbox Talks.” Leaders used these near misses to develop the “Toolbox Talk” topics and increase awareness.

“The whole safety process became part of a dialogue with our employees,” says McCann. “When employees realized they were not going to be punished, it was amazing what people would tell on themselves. In this case, there was a consequence but it was a positive consequence. They actually got recognized for coming forward and helping others learn from an ‘almost’ accident. Now reporting near misses makes someone a hero and not a tattletale.”

Polk changed the way people were looking at it. They changed the behavior. Employees began thinking of themselves as heroes and having a sense of purpose about preventing an injury or saving a life.

“That’s an act of accountability,” says McCann, “but it doesn’t feel like what most people think of when they think about accountability because it is born from affection. It’s a true desire to keep employees safe.”

MAKING GOALS ACHIEVABLE

This new approach to safety produced extraordinary results. Polk Mechanical Company’s workers’ compensation premiums dropped from a high of $1,359,091 in 2007 to $780,974 in 2013, a 43 percent reduction.

At its peak, Polk and its insurance provider incurred $1,188,734 in paid claims, and in 2013 paid claims dropped to $31,327, a reduction of almost 97 percent.

In 2012, the Associated Builders and Contractors (ABC), a national construction industry association, awarded Polk Mechanical Company its National Safety Excellence Award as one of the safest firms among its peers in the United States. In 2013, Polk Mechanical Company was awarded ABC’s Pinnacle Award, recognizing the company as the safest mechanical contracting company in the United States.

“The trophies are a cool thing, and the national recognition is nice,” says McCann, “but what’s more important is that the awards recognize the safety revival that we put in place has done the job it was intended to do, which is to make safety a core part of our culture. We drove a behavior change and proved that we can create a positive environment where our people take the lead in operating in a safe way and looking out for each other.” When Polk Mechanical started the safety revival process in 2006 the company was incurring more than one injury every month. In a safety meeting, McCann asked his 300-plus employees a question: “Who thinks we can go a year without an injury?” Not one person raised their hand. “Who thinks,” asked McCann, “we can go a month without an injury?” A couple of people raised their hand. “Who thinks we can go one day without an injury?” All employees in the room raised their hands. “Our call to action,” recalls McCann, “was easy: ‘When we leave the safety meeting tonight, tomorrow will be the first day we go without having an injury.’ And when we went that day without an injury, we challenged our team and said, ‘Guys, we did it. We made it one day without an injury. Now let’s see if we can make it two days.’ And when we had two safe days we turned that into a week, and we said, ‘Guys, we went a week without an injury. If we can do a week we can do two weeks. If we can do two weeks we can do a month, and if we can do a month we can do six months.’ And here we are, years later, having achieved a record of more than four years and more than 2 million labor hours without a recordable injury.”

Ebby Halliday called this step-by-step, day-by-day process “making first downs.” Brian Lacey calls it lowering your golf score. Fran McCann and his team achieved their safety objective by breaking it down it to manageable chunks. Each leader instilled urgency, and each made the task for their teams achievable.

“If, at the outset,” says McCann, “I had said our goal is, ‘We’re going to go a year without a reportable injury,’ I would have had a roomful of nonbelievers, and nonbelievers cannot accomplish great things. But when there’s a group of people who believe they can do it for a day, I’m just going to call on them to do it for that day. That is a victory. And they turned it into days and now all of a sudden we have got these rallying points and we have excuses to celebrate. In the big picture it gets our people to focus on the positive outcomes of their actions. It gets them focused on what they can do, not what they can’t do. That’s powerful psychology.

“The ‘a-ha moment’ for us was inviting the active participation of our employees in the process, as opposed to setting a policy and telling them what to do, which didn’t work. Now, they are the ones doing near-miss reporting. They are the ones doing the observations. They are the ones participating. We employ more than 300 workers at our company. We work in high-risk environments every day, and we do all that just with two safety professionals on staff, one in Houston and one in Dallas. I now have more than 300 safety professionals looking out for at-risk behaviors every day. If I have 60 active jobs and 30 employees in service vans making service calls, there is no way two safety professionals can touch every employee over the course of the year. It’s just too many people spread out. Now we have an army of folks who are looking out for each other. And they are not all accredited safety professionals, but it doesn’t take an accredited safety professional to recognize at-risk behavior.

“What we’re talking about is accountability,” he says. “I think the big mistake that so many companies make is they think accountability is what you do to employees to hold them accountable. For us, accountability is really all about what we do for employees to show how much we care about their safety and what they do for themselves as well as holding each other accountable: ‘I am my brother’s keeper.’”

YOUR THOUGHTS ARE A TRAIN

“It’s just a different way of looking at things, of thinking about things,” says McCann. “Your thoughts are like a train. They’re going to take you somewhere. So be careful what you’re thinking.”

Albert E. N. Gray was an executive of Prudential Life Insurance Company of America. In a speech to executives at the 1940 National Association of Life Underwriters annual convention in Philadelphia, he spoke plainly about why some people are more successful than others. Here, in part, is what he said:

The common denominator of success—the secret of every person who has ever been successful—lies in the fact that he or she formed the habit of doing things that failures don’t like to do. It’s just as true as it sounds, and it’s just as simple as it seems.

Perhaps you have wondered why it is that your most successful peers seem to like to do the things that you don’t like to do. They don’t. And I think this is the most encouraging statement I have ever offered to anyone.

But if they don’t like to do these things, then why do they do them? Because by doing the things they don’t like to do, they can accomplish the things that they want to accomplish. Successful people are influenced by the desire for pleasing results. Failures are influenced by the desire for pleasing methods and are inclined to be satisfied with such results as can be obtained by doing things they like to do.

Why are successful people able to do the things they don’t like to do while failures are not? Because successful people have a purpose strong enough to make them form the habit of doing things they don’t like to do in order to accomplish the purpose they want to accomplish.