10

CHANGE PRACTICES, NOT PRINCIPLES

Evolving

We continuously adapt and change our practices

to grow our marketplace leadership position.

Yesterday’s home runs don’t win today’s games.

—Babe Ruth

In 1346, in the early stages of the Hundred Years’ War between England and France, England’s Edward III had invaded France, sacking Caen before retreating to Crecy near the coast.

France’s Philip VI pursued Edward, caught up with his forces, and readied his attack. Edward’s army of 12,000–20,000 knights and archers prepared to meet a force of at least 40,000 French cavalry sheathed in armor and 6,000 Genoese mercenaries armed with crossbows.

What the English lacked in numbers they countered with superb organization and superior weaponry.

Until the Battle of Crecy, knights fought one another on horseback. But a new weapon—unleashed as never before on this day—would change the way future wars were waged.

Edward arrayed his troops in an open V toward the French in a 2,000-yard battle line, instructing his knights to dismount and his archers to move forward. Philip counseled patience but his generals, hot with emotion, refused to delay the attack. Philip’s troops began to advance without any apparent order.

Edward’s competitive advantage was the longbow. This weapon enabled highly trained archers to fire more arrows than crossbows and fire them farther with armor-piercing force. As the first wave of Genoese crossbowmen advanced, Edward signaled his archers, who rained more than 30,000 arrows down on the Genoese such “that it seemed as if it snowed.”1

Thousands of the Genoese crossbowmen and then thousands more French knights and their squires were killed in the first few minutes of battle, disrupting what order existed and devastating morale.

At the conclusion of the eight-hour battle, the French had lost up to 10,000 men while the English just several hundred. The victory at Crecy went to Edward because his approach to an old problem had evolved.

SONY’S MODERN-DAY BATTLE IN WALES

The longbow helped the English win the Battle of Crecy and changed the way battles were fought for the next 50 years. Accountability can help you win your toughest modern-day battles.

Accountability is a set of beliefs as much as a set of actions, and it may be the deciding factor that drives you and your team to accomplish a task or achieve an objective despite heavy odds stacked against you.

Of the executives I surveyed, 75 percent agreed with the statement: “We regularly ask, ‘Is there a better way?’”

For Steve Dalton of Sony, there was no other choice but to find one.

In 1973, Sony opened its first Western European plant in Bridgend, South Wales, to manufacture color TVs and later began producing its cathode ray tubes from the same facility. The superior quality and worldwide demand for these products earned Sony three Queen’s Awards for export achievement. A second Welsh plant at nearby Pencoed was built, and in 1992 Queen Elizabeth officially opened the factory.

“I moved to the managing director position just as TV production was dying,” Dalton told me. Sony closed the Bridgend factory that had been making cathode ray tubes on a 24/7 basis, and as the layoffs reduced headcount in Wales from 3,500 in 2005 to 250 people, it fell to Steve Dalton to sell the Bridgend factory and terminate people he’d worked with for a long time. “It wasn’t a pleasant exercise,” Dalton recalls with classic British understatement.

Dalton had four battles to fight, and he won all four: First, Dalton’s peers at five other Sony manufacturing plants in Europe were each vying to continue their plant’s operation; only Dalton’s plant in Pencoed, Wales, remains. Second, Dalton transformed the business. Third, he transformed the employees. Fourth, he won the first three battles just in time to face a worldwide recession and come out ahead.

CHANGE IS DIFFICULT

“There is nothing more difficult to take in hand, more perilous to conduct, or more uncertain in its success,” said Niccolo Machiavelli, “than to take the lead in the introduction of a new order of things.”

Change is difficult for many because:

![]() We’re giving up one thing for another. The more we have to lose—money, our job, prestige, power, a relationship—the more difficult we find change.

We’re giving up one thing for another. The more we have to lose—money, our job, prestige, power, a relationship—the more difficult we find change.

![]() It’s often prompted by pain. We may see opportunities that require change, but usually it’s a problem that forces us to take action.

It’s often prompted by pain. We may see opportunities that require change, but usually it’s a problem that forces us to take action.

![]() Things usually get worse before they get better.

Things usually get worse before they get better.

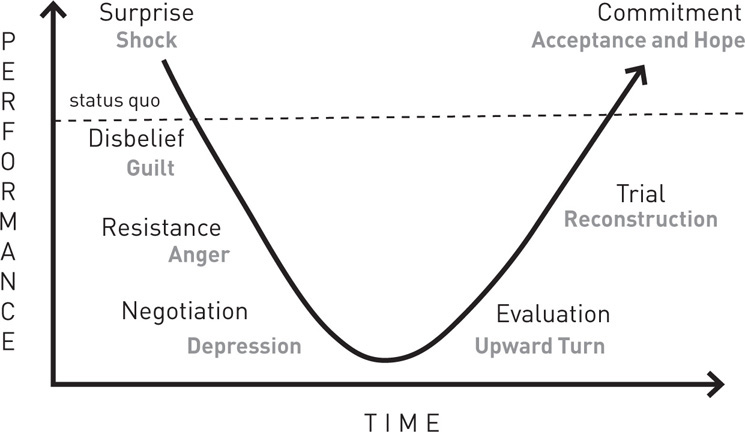

Financial analysts call this type of change the “J curve.”

Counselors call it the “Seven Stages of Grief.”

Figure 10.1 The Seven Stages of Change and the Seven Stages of Grief

As you and your team move through the type of change management program Steve Dalton implemented, remember the importance of addressing the emotions that accompany the logic of change.

“You must always keep asking yourself, ‘What if, what if, what if? What if this doesn’t come up? What if we don’t get it? Do I have a plan B? Have I got a plan C? Do I know what I’m going to do when that happens?’ Now some people call that pessimistic thinking,” Dalton says, “but I believe you can be realistic with confidence and that is how you have to think now. Business is so unpredictable. You have to know with your eyes open what you’re going into, otherwise you could be in a sticky position.”

SONY’S BUSINESS MODEL EVOLVES

In Peter Drucker’s 1964 landmark book Managing for Results, he repeated what he first wrote a decade earlier: “The purpose of the business is to create a customer.”2 Drucker also believed that “economic results are earned only by leadership, not by mere competence.”3

A leader must accept that customers’ needs are always changing, and so the company you’re leading must be ever-evolving. Therefore, two of the most important questions a leader must ask and answer, said Drucker, are “Who is our customer?” and “What does the customer value?”4

An organization’s top leader is responsible for getting answers to these questions and accountable for executing the changes that will enable the company to provide the products and services customers want. Of the executives I surveyed, 79 percent responded that “In the past 24 months, we have developed and introduced a new product or service based on customer feedback.”

To obtain meaningful customer feedback, says Dalton, “you have got to get close to them; you have to have a relationship with them, because if you are not satisfying them, they’ll go elsewhere.

“Take our broadcast camera, for example. We’re not a pure manufacturer, so we don’t design on the site. The designing is done by Japan, but our business development people work with the major broadcasters in the United States, in Japan, and in Europe. Maybe the customer doesn’t always know what they want. Maybe they’re asking Sony, ‘What technology is next? How good is this picture going to get that I’m going to shoot with these cameras?’ In those cases, it’s our job to show them.”

Dalton characterizes the Wales operations in 2005 as being in “quite a dangerous place,” and he made three critical strategic decisions based on customer feedback that saved the business.

First, Dalton changed the products Sony was manufacturing at the Pencoed plant.

“We had been making broadcast cameras since 2000,” says Dalton, “and one of our biggest export markets was the United States, so we’d seen the recession there two years before it reached the UK. We’d seen what was being reported in the U.S. and it was showing up in our sales data. We knew it would be a ripple effect in the UK so we started to think TV wouldn’t be here forever. The end came very fast. The real urgency came in 2005, so for us it was, ‘Okay, we better do something.’ We had to reinvent ourselves.”

Dalton transformed the Pencoed business from a manufacturer of low-value, high-volume products into a manufacturer of high-value, low-volume products. The plant is the only facility outside Japan to fully manufacture high-definition professional and broadcast camera equipment that includes the latest Blu-ray Disc technology, and this equipment can be found in sports stadiums, in studios, and outside broadcast units around the world.

Dalton’s second critical decision was to change the business model by expanding significantly Sony’s customer service business.

Dalton’s team wasn’t supporting the entire Sony portfolio, so it pursued new broadcast business from within while also pursuing third-party business more aggressively. They also moved from relying on just one product in only one market (i.e., selling to themselves) to diversifying customer service, expanding their repair business for Sony, expanding the camera business, and launching non-Sony third-party manufacturing contracts. Dalton’s team began managing most of the bulk returns and postal returns of all consumer products on a seven-day repair turnaround as well as the high-end professional camera repair for all of Europe. “We’re much more diverse, much more multiskilled,” says Dalton, “and the things we’re doing today are actually far more complicated than making TVs.”

Dalton’s third critical decision was to create a state-of-the-art business incubation center for start-up companies in the media, digital, gaming, and renewable sectors. Today, the Sony UK Tech Centre is home to 28 organizations.

“We have got to keep moving, keep evolving, raising the bar,” says Dalton, “otherwise we will fall behind. Since completing the transformation of our business model in 2006, we have been profitable every single year.

“It’s always been a challenge,” he says. “That’s without a doubt. I’ve found the last year one of the toughest, probably in my lifetime.”

Changing a business model takes smarts and guts. Transforming people is even harder and takes leadership.

“ARE WE NEXT?”

Of the executives I surveyed, only half (50 percent) said they “strongly agree” or “agree” that “New approaches and initiatives are received enthusiastically versus being resisted.”

For Sony’s remaining employees at the Pencoed plant in Wales, everyone’s future depended on whether employees would take ownership of the new plan Steve Dalton was proposing or resist it. Dalton says that of all the pieces of the turnaround plan, the “most difficult transformation was the change management program” he led with his employees.

“We’d gone from making TVs to saying, ‘We’re going to teach you how to talk to a customer when they walk through the door.’ ‘We’re going to teach you how to service a customer’s product.’ ‘We’re now going to teach you how to negotiate a contract with a third-party company.’ That was a whole new ball game for our people. For an engineer or technician, they just opened a whole new box of tricks.”

The steps of a change management program, says Steve Dalton, are “not rocket science: casting a vision for the future, getting change agents on your side, getting some quick wins, communicating your vision without exception to everyone, achieving buy-in, and figuring out how to reward people. Yes,” he says, “many people know those steps.

“The issue for me was this: You have got to believe in it yourself if you’re a leader. And how you implement and execute your plan is the key.

“When we were left with 250 people, most of them were saying, ‘Okay, when are we next, Steve?’ One of the biggest obstacles to overcome was to get people to understand there is life after the TV business. The communication started with me. I stood up once in front of our senior team to talk about our turnaround plan at the time, and when I went home my wife asked me, ‘How was your day?’ and I said, ‘I think I’m the only one who believes we can survive more than six months.’ But I did believe and we achieved the vision we set for ourselves.”

Dalton rallied his troops with honesty, hope, empathy, and accountability.

THE PARTHENON

“The soul,” said Greek philosopher Aristotle, “never thinks without a picture.”

Steve Dalton borrowed from the Greeks by depicting his plan for the future in a pictorial vision of the Parthenon.

“We called it the ‘picture of perfection’ vision, and that was our first midrange plan at that time,” says Dalton.

The vision consisted of three major components that served as the Parthenon’s base:

1. Financial competitiveness. “We had an index measure of our cost per square foot that we had to reach that would allow us to make quotations for new work and not be considered too expensive.”

2. Differentiation. “We had to differentiate ourselves in our customer offering. We called it ‘the obvious choice.’”

3. Heroes. “We needed heroes, people with good knowledge who were willing to learn new skills and put that new knowledge to work. We’ve got this thing about kaizan, or small improvements, so we have a requirement that everybody must participate in one kind of innovation activity at least once each year. We put it in their performance document. And we measure it and we hold people accountable.”

The columns of the Parthenon represented lines of business (cameras, OEM equipment, service, etc.) that the plant would now focus on given its change in product mix.

Dalton stopped production for two days and brought all of the employees together in two different groups on consecutive days.

“You don’t get trust without being honest,” says Dalton, “so I opened it all up to them.” Dalton reviewed the financials, described operating costs, examined sales forecasts, and shared profit targets. Dalton told them that these were the key financial indexes and explained that Sony would need to capture the high-definition broadcast system and also capture and service other products to survive and then grow. “No one who ever ran this plant in the previous 40 years ever showed financial information to our direct workforce,” says Dalton.

He made it clear that he didn’t have all the answers, so he organized the employees into small groups, encouraged their input, and then posted their ideas. “They felt they had given the answers to some of the problems,” he says.

Toward the latter part of the employee meeting, Dalton did something so simple its impact on his team surprised even him. “I put at the top of ‘Parthenon’ a date of ‘2010,’ and we were in 2006 so that was our four-year plan,” says Dalton. “And that was the most significant thing that made people realize there’s a future because I told them we were going to do all these things and we would still be here by 2010.”

TREAT PEOPLE LIKE ADULTS

Highly skilled people were working on the shop floor at base wage, and Dalton remembers that when he had been in their shoes he believed he had the latitude to perform his job. So Dalton made a symbolic change that demonstrated his belief in his employees.

The plant had a claxon that would sound for each of the departments’ breaks, and sound again when the break was over. All over the factory. All day until the end of the day. And again in the morning to start a new day.

Dalton switched it off.

“I told them. ‘You don’t need a beeper to tell you when to go to break or to come back. You know what the time allocated is. You know what job we have to do. I trust you will do it because you’re adults.’ So after 30-something years,” he says, “I switched it off and cut the wires. That was one of the simplest things I did early on to say, ‘I trust you, do your job.’”

COMMUNICATE, COMMUNICATE, COMMUNICATE

Dalton kept up a steady communications drumbeat.

“Lots of people tell me, ‘Oh, yes, I’m communicating.’ And I say, ‘Hang on, I sit here with these employees and this poor fellow over here has never heard about that new product or new scheme.

How can it be that you’re telling me you’ve done it?’ And this manager or leader of this team might have only said it once and then thinks that is enough. So that sort of thing—communication—is not difficult to think about,” says Dalton, “yet it’s not easy for them to do when it comes to the actual implementation of your plan. You’ve got to ask and answer, ‘Did the message get through?’”

To ensure that his message was getting through, Dalton developed digital signage that’s displayed around the plant, created a weekly paper bulletin that’s posted in the canteen, launched a blog on the plant’s internal Internet for employees, and distributed a quarterly bulletin.

Making yourself visible to your employees and showing them that you care are smart steps for a leader to take under the best of times, and they are essential when the uncertainty of change causes anxiety among the workforce. Dalton formed a 12-person employee consultation committee that he meets with regularly to check morale, listen for new ideas, and determine whether any barriers are obstructing performance that he can remove. He also formed a breakfast club comprised of employees from all over the organization. “I sit for an hour and have breakfast with them in the middle of the canteen so everyone can see it and we talk about topics and they can ask me anything they want,” he says. “That’s a great way of sharing information and listening to what they say.”

ACHIEVING THE TURNAROUND OBJECTIVES

By the end of 2006, the plant had produced its first high-definition camera. “That was something fairly early that we set our minds on and we succeeded,” says Dalton. The plant celebrated the success, and Dalton wrote, signed, and sent personal letters to people that said, “You did a great job. You did a job that aligned yourself with our values. ‘Speed, teamwork, accountability, and focus.’”

He also put his money where his mouth was.

“I gave a performance-related bonus to this production site. I had said, ‘When we achieve profits for this level of our budget, I will share some of that with you.’ We made the profit and I shared it with them. I don’t think they could believe that.”

The plant turned around, and, as is always the case, it was the people who led the way. A time of adversity unleashed Steve Dalton’s leadership and revealed his team’s full potential.

“We’re laughing today and having fun along the way,” says Dalton, “but we’ve got to be realistic. People can never say, ‘You didn’t tell us this, Steve,’ so I can say, ‘Yes, I’ve been telling you this, so come on.’ That’s why people are up for the challenge.”

Towers Watson conducts an anonymous survey every year across Sony’s 160,000 employees with 13 indexes measuring areas such as leadership, communication, engagement, values, and performance against objectives. Dalton’s employees have moved from turnaround mode to setting the bar globally.

“We have been improving bit by bit,” says Dalton. “We have the highest scoring across all the Sony organizations. We smash the global company benchmark; we smash the European UK benchmark. We are now higher than the global manufacturing company benchmark. An ultimate goal is a high-performance global company of any kind and we’re two or three indexes off hitting that, so I know we’re getting it right.”

In 2013, Sony’s Pencoed, Wales, plant was recognized by Cranfield School of Management, one of Europe’s leading university management schools, as the “Best Factory in Britain” as benchmarked against other companies. The Sony plant also was named “Best Electronics & Electrical Plant” and received the “Innovation” award. “Sony’s facility in Pencoed is a high performance plant in every sense,” says Dr. Marek Szwejczewski, director of the Best Factory Awards program, now in its twenty-second year. “It has a highly skilled workforce, state-of-the-art electronics manufacturing equipment and processes, and a visionary and proactive leadership team, who are ensuring continued growth. The factory’s unique combination of skills meant that it recently started production of a range of professional camcorders, the only factory in Europe to do so for Sony. The fact that global production of the new Raspberry Pi minicomputer moved from China to Pencoed is testament to the factory’s ability to manufacture high-quality products.”5

GET ON THE SHIP

Dalton transformed the culture at Sony’s Pencoed plant from one that had been linear and hierarchical to an environment where adaptability and accountability were valued and rewarded, and the employees shared a sense of ownership in achieving the “picture of perfection” depicted in Parthenon.

Yet as often happens in every organization, it seems that some are either happy with the ways things used to be or unable or unwilling to perform at the new levels required.

As the Pencoed turnaround moved into its third year and new customers were being acquired and profits were returning, Dalton faced his next toughest decision: addressing members of the leadership who hesitated in taking action aligned to the agreed-upon vision and values. “They were nodding ‘yes’ in meetings,” says Dalton, “but implementing different things against our values inside the operation. I got wind of this behavior and I tested it out a few times. Now, I’m a patient person, and I worked with them, and I’d say, ‘You know what has got to be done now,’ and they would say, ‘Yes, I understand,’ and then when it gets down to it, they can’t perform. After 12 months of this behavior, I met privately with each individual and said, ‘I’ve given you enough time, this ship’s got to go this way, you’re not moving in the same direction so you’re going to have to get off. I’m sorry.’ And that was tough because I knew them personally for a long time. But it had to be done because they were slowing the progress for the rest of our 400 people.” In his 30 years with Sony, Steve Dalton has seen his share of change and adversity. Just as his British ancestors responded to the French at the Battle of Crecy with new strategies and a new weapon, Steve Dalton responded to an upheaval in the market by changing his business’s product mix, evolving the Pencoed business model, and reshaping the culture so that trust and accountability are now the bookends of high performance.

“What I’ve learned in the past 12 years,” says Dalton, “is never think you are safe. Yes, celebrate success, and do it is much as you can, but the battle carries on.”

EMBRACING CHANGE AT MARRIOTT

Most people resist change.

Bill Minnock drives changes every day for Marriott International.

William F. Minnock III is a 30-year Marriott veteran and senior vice president of Global Operations Services where he’s responsible for program management and deployment of the company’s product and service innovations for all 18 brands worldwide. In this position, Minnock also oversees the communication, training, and quality assurance aspects of performance improvement programs in the company’s sizable portfolio, and these changes can range from implementing a new breakfast program systemwide and leading a new design and décor scheme modification to updating changes in technology.

Minnock has held senior vice president positions for the company’s architecture and construction division where he oversaw finance, for its resort development for Marriott Vacation Club, and for the company’s asset development management group. Like nearly half the company’s managers, Minnock has also served as general manager of a Marriott hotel.

One of Marriott’s values is “embrace change.”

Since its founding by J. W. Marriott, Sr., in 1927, the company has evolved from a nine-stool A&W root beer stand to an international company of 18 brands with 3,700 properties in 73 countries and territories. Bill Minnock is in the middle of change at Marriott.

“We tell people that if you want to be part of our culture you have got to expect change,” Minnock told me. “We’re always trying to do things better, whether it’s the check-in process, how we prepare food, how we serve guests, how we clean rooms. To continue to be excellent, which is another one of our values, you’ve got to evolve. There’s truth to this statement and we use it all the time: ‘Success is never final.’

“Each one of the disciplines is constantly trying to figure out how to evolve the business model given changes in the economic environment and changes in travel patterns and preferences,” says Minnock. When ideas have potential, Marriott names a person to lead that initiative and gives them the appropriate level of resources to test the idea and develop a proof of concept to determine whether that new idea will work. “They’re accountable,” says Minnock, “for driving implementation of that new idea.”

Marriott has a “bias for action,” says Minnock, “and that means let’s study it, but let’s study it a little less longer than we used to do back in the 1980s.”

Marriott has moved decision making closer to the customer to increase the odds of getting it right the first time. When a new idea is proposed, Marriott considers the desired outcome, gathers insight from consumers, studies the competition, and then relies on the team’s expertise as it moves rapidly to test, observe, obtain feedback, evaluate, and enhance the concept. “When you’re driving product and service innovation projects from start to finish,” says Minnock, “you need stage gates along the way for decision points. You need to make sure you’re doing good work, but at the end of the day you’ve got to get it done.”

As you would expect from a multinational company with lots of stakeholders, ideas encounter more people who can say “no” than “yes.”

“The way we push new ideas over the finish line,” says Minnock, “is, first and foremost, by doing good work. We also do a lot of stakeholder assessment and communication to get feedback and buy-in along the way.”

Marriott has been extremely successful for decades. “We are clearly the leading portfolio of brands with the baby boomers,” says Minnock. “We need to understand the Gen X and Gen Y consumers as well as we understand the baby boomers, so the change we’re driving now is all about the next-generation consumer. Let’s use Courtyard ‘Refreshing Business’ as an example of how this brand continues to evolve.”

EVOLUTION MEETS URGENCY

In 1983, Marriott responded to changes in business travel with a risky bet: its launch of its Courtyard by Marriott concept, a 150-room hotel concept that debuted in Atlanta. “We surprised everybody,” says CEO Bill Marriott. “Competitors came out to take a look and said, ‘It wouldn’t work.’ And it worked.”6

“Courtyard by Marriott was a real home run when it was launched in 1983,” says Minnock “but in the mid-2000s it had started to lose some of its preference.”

Courtyard was losing ground to competitors as measured by guest satisfaction and revenue-per-available-room index.7

The next evolution of this storied concept—a repositioning program called “Courtyard Refreshing Business”—was a textbook case of Marriott’s “bias for action.”

“As we looked at the evolving customer base and did a lot of customer analysis and research,” says Minnock, “we decided we needed to completely reposition the restaurant and the lobby area at Courtyard into a much more inviting all-day atmosphere. We redesigned the entire space and redeveloped the menu offering with the result that a more activated, more energetic lobby at night makes it much more comfortable for people to relax, for small meetings to occur, to spend time with your associates in an inviting space to shed the day. This move has really repositioned the brand.

“In order to get that Courtyard refresh decision approved, Janis Milham, the brand’s VP and global manager, was the advocate,” says Minnock, who estimates that up to 100 people at Marriott worked with outside architects and Marriott’s ad agency to push the refresh idea over the finish line. “We needed to get Marriott’s operations organization aligned with the idea, and it was a big operating change. The franchise organization had to believe the idea made sense. And ultimately the senior executives of the entire corporation had to buy in on the idea, right on up to Bill Marriott, who definitely weighed in on the decision. Getting all of those stakeholders to agree that this was the right answer was a major, major challenge.”

That’s because the Courtyard refresh was another big bet by Marriott and its franchisees: $750,000 per property, about twice the investment of a typical renovation.

Minnock says implementation was “pretty darn quick.” Marriott identified the issue, completed the analysis, achieved buy-in, and developed the first in-hotel mock-up in just nine months. Most of the 900-plus Courtyard hotels completed the upgrade within an astounding five years.

Minnock says the evolution of Courtyard by Marriott is “a great success story and the brand is realizing improving revenues and increasing market share.”

SEVEN WORDS YOU CAN’T SAY

Comedian George Carlin was known for mixing observational humor with larger, social commentary.

His groundbreaking 1972 album Class Clown featured his most famous monologue, “Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television.”

Regardless of what you think of Carlin’s brand of humor, the point is that he spent a lifetime appreciating and poking fun at the power of words. Words, after all, give voice to our thoughts. A thought that’s spoken, then acted out, produces a result. The result can be good. Or the result can be bad.

George Carlin had his seven words, and here are seven you shouldn’t say:

“We have always done it this way.”

If you are serious about getting better, you must be fully committed to considering new ways of running your business. Do not change your principles. You must, however, be willing to look critically at changing your practices—your business proposition, your programs, your processes, your people—to evolve and propel your organization to the next level of success.

The flip side of “always” is “never.” Here are five other words that will kill your efforts to evolve, improve, and achieve your organization’s performance potential:

“We’ve never done that before.”

Ron Farmer doesn’t use those words, though he has found himself in some tough spots.

You met Farmer in Chapter 2 and may recall that he founded US Signs, and then led his company through nine tough months the company’s first year as well as through three recessions before selling his company for top dollar 31 years later. Farmer started a second company, US LED, and this company was an Ernst & Young Entrepreneur of the Year finalist.

Of the executives I surveyed, 77 percent said they “strongly agree” or “agree” that “We won’t compromise our values, but we appreciate that mistakes can lead to breakthroughs.”

Farmer would readily admit that he’s made mistakes along the way, but he’s made a lot more great decisions than poor ones, he’s never compromised his principles, and he’s had more than his share of breakthroughs.

STARTING US SIGNS WITH NOTHING BUT A PHONE

In 1979, Farmer accepted an out-of-state company’s offer to start a new operation in Houston with a pay structure that would enable him to triple the $41,000 he’d made the previous year, and “that was big money in those days,” he recalls. Farmer sold his home in Austin, moved his family to Houston, and then traveled to the company’s headquarters in Wisconsin to sign the agreement. But the company owners reneged on their commitment. “They had me trapped because I had no cash,” says Farmer, so he returned to Houston and went to work. During each of the first five months, he sold more product than the company could produce and was paid just $1,750 the month of his record-breaking sales effort. He realized these “were not nice people,” so he made plans to start his own company.

Farmer rented a building and purchased equipment and office supplies. On his last day with his current employer, he cashed his most recent paycheck because he “didn’t trust those guys.” With high expectations and enthusiasm for his future he went to his new business and discovered that someone had broken in and stolen everything—all of the production equipment, supplies, pads, paper, pencils, the pictures on the wall, the chair behind the desk. Everything. The only things left were a desk and a telephone. That was the first day of US Signs.

“It was a scary moment,” Farmer admits. “When I called my wife that Friday and told her what happened and she asked, ‘What are you going to do?’ I quickly realized my answer and replied, ‘The only thing we still have is this red telephone in my hand. I’ve got 30 days before I get the phone bill and eight or nine days before I pay them, so I’ve got that much time to figure out how to make this phone make money. I’m going to call people I know in the sign business, find out what they need, and accumulate enough orders to buy quantities where I can make some spread.’ I was temporarily in the sign supply business. I made enough money to buy equipment, and, little by little, I started my sign business, which, by the way, was a business I knew almost nothing about.”

Farmer’s new company grossed $186,000 its first year and grew to $2.2 million in five years. This performance landed US Signs at 196 on the Inc. 500 list. In between the start-up and the sale,

US Signs was profitable each of those 31 years except 1986, 1991, and 2001.

LOOKING FOR A BETTER WAY

In 2000, US Signs was looking for a better way to light signs.

Using LEDs (light-emitting diodes) was an appealing solution because LEDs use less energy than neon, won’t short out, and last longer. Only eight companies manufactured LEDs for signs at that time and in just one color: red. Farmer bought samples from all eight companies, chose the best and started using them. He believed in LED lighting to such a degree that he proposed a $3 million retrofit of all his top client’s signs. Realizing he needed a better product, he engaged Mike Wilkinson’s firm Paragon Innovations to help develop his own product and launched US LED in 2001. In four months, US LED was in the market with its first product. Over time, US LED developed all colors, including white, which is now an industry standard.

“From the time I was little,” says Farmer, “I was always the kid willing to work.” Along the way, Farmer learned three important lessons as an entrepreneur.

First, his way of solving money problems—whether as a kid or as an adult—was often to start a company. “When I saw opportunities,” says Farmer, “a new company was not far behind. I even helped my employees and others start companies when we changed to an outsourcing model.”

Second, he realized that change is profitable and that he is an innovator. In 1986, when one-fourth of all sign companies in Houston were going out of business, Farmer changed his business model from a manufacturing operation to a sales operation, outsourcing all manufacturing. “That approach,” says Farmer, “was denigrated by the industry, and for years our sales people were reluctant to reveal that we didn’t manufacture what we sold.” Today, this model is more accepted. About that same time, the use of aluminum extrusions was growing, but virtually no company made their own extrusions. Farmer developed two aluminum extrusions that gave his company a decided advantage. “Most inventions are not original,” says Farmer, “and the things I did with our business were mostly evolutionary.”

Farmer’s third, and, he believes, most important lesson, was his ability to make decisions with imperfect information. “You’re going to come to impasses where you can’t see beyond the veil,” says Farmer, “so if you’re going to make it in business, you have to be willing to make decisions without all of the information and show by your deeds how much you really believe in yourself and your ideas. In every case where I’ve been willing to put the last dollar on the line, we’ve made it.”

HOW MANY CHANCES AT ACCOUNTABILITY?

A lot of variables go into deciding how many chances to give someone.

“There’s no bumper-sticker slogan, no one-size-fits-all answer,” says Farmer. “We, like most people, probably keep underperforming employees too long. But you’ve got to give people time to show signs of development.”

At Farmer’s company, outside sales reps get 6 to 12 months to show their willingness and ability to grow or they are dismissed. For the inside team, Farmer considers several factors. “Sometimes we promote up and find out they can’t do the job,” he says. “We don’t fire them just because we made that mistake. We’ll find someplace else for them in the company if possible. We’ve created a lot of goodwill in the company doing that.

“If there’s a mistake,” says Farmer, “and someone says, ‘I didn’t think my way through that’ or ‘I didn’t understand that,’ those are a different class of mistakes. But when I’ve trained someone and everything is understood and the person performs several times correctly and then they do it wrong, I’m not very forgiving. Unless there’s a really great explanation, they’re probably not going to stay.”

Farmer once caught an employee sleeping in the bathroom and that person was gone in 15 minutes. Other decisions aren’t as straightforward.

“There was one instance where a really good employee was disrespectful to another employee” says Farmer, “and I asked the employee who had committed the infraction to do certain things—apologize, go through some training, the normal stuff—and he said he would do it and then he didn’t follow through. Now keep in mind that this guy is really smart, really good, and I didn’t want to lose him. But I had to let him go. If you are unwilling to keep your word, what are you doing with our clients and other employees?”

Some people are better interviewers than workers.

Farmer says that if he asks someone to do something they can’t do, then it’s his misjudgment. But when he asked someone to do something they said in the interview they could do and they are unable or unwilling to perform, they may not have a place in the company. “Accountability for us,” says Farmer, “is tempered by giving people the benefit of the doubt. But when there is no doubt, I must act, because I’m accountable, too.”

WESTERN GRAPHICS: ADULTS DON’T ARGUE WITH REALITY

Western Graphics is a commercial printer in St. Paul, Minnesota, founded in 1967. CEO Tim Keran purchased the business from his father, who purchased the business from his partner, who purchased the business from the founder.

The company’s counterintuitive tagline reflects Keran’s commitment to continuous improvement in order to deliver the most value: “Helping our clients print less.”

“We’re a pretty small company,” Keran told me, “so when a big customer leaves or a key employee leaves it hits the bottom line and it hits the emotional line harder and faster.”

Keran saw the worst recession in 80 years heading his way and told his employees in their monthly meetings that the approaching storm would either hit the company directly or move past them.

“I often say, ‘Adults don’t argue with reality,”’ says Keran, “so we reviewed finances, shared team-by-team results, and recognized employees for their performance while we were providing monthly updates that showed the recession was moving from storm watch to storm warning.”

GETTING BETTER AS THINGS GOT WORSE

The storm turned into a Category 5 hurricane.

“While we were going through the storm, it didn’t make sense for us not to get stronger,” says Keran. “We used those two years during the Great Recession to make improvements. While things were getting worse around us, we were getting better.”

During the recession Western Graphics continued its streak as a six-time recipient of Printing Industries of America’s Best Workplace in the Americas award, which is based on eight criteria, including management practices, training and development, financial security, and work-life balance. Keran earned national recognition from the same organization for his “success at creating a culture that has inspired Western Graphics employees to share their knowledge and creativity.”8

By virtually any yardstick, Western Graphics got better while everything around was getting worse: sales per employee increased 22 percent, rework improved 74 percent, employee morale improved from 3.87 to 4.06 (out of 5.00), and the company’s profitability allowed incentive bonuses to be paid for seven consecutive quarters as the recession ended.9

Keran says the company’s values guided them through the tough times: team, trust, attitude, and results. “Because we had a healthy accountability culture,” says Keran, “we were able to rely on teamwork, attitude, and trust to drive results. We continued to build trust with our communications going into the recession, and we were open about what was happening. We didn’t let the economy be the excuse, and this allowed people to say, ‘Okay, we’re not going to be in fear mode, we’ll pick up a shovel and get something done.’”

IDEAS DON’T COUNT

To survive an economic downturn while the printing industry moves through seismic change, Keran kept things simple, fun, and connected to his employees’ day-to-day work. The company’s definition of “Results” is “We continually get better,” and it’s mandatory to make improvements. “Half your job is making your numbers,” says Keran, “and half is making your job better.”

Here’s how Keran and his team drive improvement:

“Ideas don’t count,” Keran says. “An improvement is an idea that’s completed. It can’t be regular work. It has to be something that makes your work better, your department better, or the company better.”

Keran encouraged his team to view improvements as positive versus mistakes. “There’s a saying that problems are gold,” he says, “and finding gold makes you rich. So we were happy to see the mistakes because to us it’s a way to get better. We celebrate mistakes in kind of a twisted way.”

Employees drive improvement. “We built the system,” says Keran, “so our people could lead their own improvements instead of us trying to manage them to make improvements.”

Keran employed an annual theme to make the continuous improvement journey fun while getting better and accomplishing more.

Past themes include Real Estate Tycoons, Crime-Solving Detectives, Pirates, and Survivors. “The first year we felt a little weird,” says Keran, “but I got people dressing up in ’80s gear for the meeting. Fake long hair, tattoos, and bandanas. You think it would wear off on adults, but it’s still a way of having fun while we’re getting better. And then some employees created these medals for ‘Best Improvement’ winner for the month. I thought they were kind of cheesy, but people love the medals and love to keep score. People want to be part of something that just flat-out works. We’ve got to get better every day.”

For many, change is stressful. “Business,” says Keran, “is a game, so let’s have some fun around that. And then let’s go home and take care of the real-world stuff.”

Keran encouraged small improvements, the smaller the better. “If you start asking for big, crazy $20,000 ideas, then a lot of people say, ‘I can’t play that game. I don’t have an MBA. I don’t have a project management degree.’ So we stayed simple, saying, ‘Is this going to make you, the department, or the company better?’ If ‘yes,’ then it counts as an improvement.”

Western Graphics developed a process called the “system bust,” a one-page form on bright lavender paper that employees complete every time something doesn’t work as intended, from parking lot lights, to equipment problems, to missing a deadline.

Keran also instituted a profit sharing plan that rewards employees for improving efficiency and driving customer satisfaction.

Western Graphics averaged 300 improvements per year before the recession. “In the middle of the recession,” says Keran, “we got up to 650, so we doubled our improvements during one of the worst years we had.”

APPLYING THE LEAN PROCESS TO COACHING

Western Graphics’ commitment to accountability was an outgrowth of the Lean manufacturing process developed by Toyota to eliminate waste.

“Lean really launched us into our accountability culture,” says Keran. “Our attitude became ‘We’ve got to get better. Let’s find the better way.’ You should do that every day.”

Productive employees are happy employees, and Western Graphics discovered that as morale improved so did performance. Turnover and quality defects decreased. “We asked, ‘Why wouldn’t this approach work with performance reviews? Why wouldn’t this work with coaching people instead of managing them?’”

Western Graphics scrapped its twice-a-year performance reviews and moved to coaching conversations every two weeks with quarterly reviews.

“It’s great for the employees,” says Keran, “because they hear about what they need to do to get better. It’s easy on managers because they can get it off their chest right away instead of thinking about it for six months. If you’re coaching people on poor performance, it’s difficult if you’re doing it once or twice a year. If you’re nudging them every two weeks and every 12 weeks, you are really telling them the score on their performance, that’s easier and less stressful for the manager and for the employee.”

The process borrowed from Lean, says Keran, “is one of feeding forward versus feeding back because there’s nothing we can do about the past. We’re giving you information every two weeks so that you can perform better. With an annual review it’s all feedback. Now, it’s an opportunity to say, ‘Let’s not worry about the past, this will be an opportunity to get better.’ You’re building trust instead of fear.”

YOU CAN’T QUIT AND STAY

Every leader I spoke with has a similar but slightly different take on addressing underperformance, but it all starts with clear expectations and then moving quickly to celebrate a coaching victory or separating the underperformer from the company.

“Tell people the score,” says Keran. “They all want to know what the score is. And they want to know how the company is doing. They want to know how their department is doing, and they want to know how they are doing. Why is their performance rating in your head? They can’t hear what you’re thinking. You’ve got to share the score.”

For underperformers, Keran says, “Don’t allow people to quit and stay because that’s not good for anybody. It’s not good for you as a leader, it’s not good for the people who are around them, and it’s not good for them. So when someone won’t perform and they quit and stay, we get rid of them immediately.”

When things got tight during the Great Recession, Western Graphics laid off 10 percent of its workforce. “We did them on merit,” says Keran, “not based on seniority. We terminated a great guy. People were emotional about it. I was emotional about it. But he just wasn’t one of the people we were going to keep. How we handled that layoff built trust because we said, ‘If you do your job and you help yourself get better, your job is safe.’”

Nice people who can’t or won’t do the work can be the toughest terminations, but, says Keran, “they just don’t fit our core value of ‘results.’ They are the right person at the wrong company.”

NUCOR’S MOUNTAIN WITH NO TOP

Nucor acquired Magnatrax in 2007, and Ray Napolitan was promoted to lead one of the four brands, American Buildings Company. When I visited Ray in Eufaula, Alabama, the Great Recession was in full swing.

Napolitan had already begun the evolution of transforming the company into a high-performing company, and the previous year the plant’s production rose 14 percent with fewer workers.

Nucor’s response to the recession, Napolitan told me, was “to train our folks, develop techniques, improve our processes, and get ready so that we will emerge stronger when the market turns,” noting at the time that “many of our folks at American Buildings Company have said they’ve had more training in the past 12 months than they had their 20-year career with American Buildings.”

Safety is at the top of every Nucor plant’s list of priorities and each year the company raises the bar, looking for new ways to keep employees safe and healthy. “The target for the President’s Safety Award used to be one-half the industry average for our business segment,” says Napolitan, “and we changed that target to one-third the industry average.”

Nucor also works with OSHA on a voluntary protection program, working side by side to identify improvement opportunities. “We don’t wait for an audit,” says Napolitan. “We reach out, bring OSHA in, and work with them proactively and collaboratively.”

In order to evolve, 69 percent of the executives I surveyed said, “We look outside our industry for practices we can adapt to our business.” Looking beyond your four walls is critical. How do you know what you don’t know?

Nucor calls its approach to bringing in the best ideas to drive performance “bestmarking.” “Bestmarking doesn’t have to be within your corporation,” says Napolitan. “We do bestmarking with outside companies—not as much as within our own company, but there’s no reason you can’t go down to your neighbors or some other manufacturing facility and bestmark.”

Proprietary information is not shared, though occasional visits to competitors occurs to examine nonproprietary issues such as safety, environmental initiatives, and quality—even ways to improve manufacturing processes that aren’t proprietary.

Improving, adapting, and evolving, says Napolitan, is like a game of King of the Mountain. “When you’re at the top of the mountain there’s only one place to go: down. So our executive chairman Dan Damico asks us to envision our business lives and personal lives as though we’re climbing a mountain with no top, so that we’re continually learning, continually improving, continually getting better, not just for ourselves, but for our entire team. When we do, we will continue to excel in the marketplace and in everything we do.”

DAN EDELMAN’S THREE SIMPLE QUESTIONS

Dan Edelman started his one-person business in 1952.

Today, Edelman Worldwide is the world’s largest independent public relations firm with fees of more than $660 million and employing 4,600 in 63 offices in 26 countries.10

For four years, I led the Dallas office of Edelman Worldwide.

Dan was a taskmaster and held his senior leaders accountable for four things: providing great work to existing clients, winning new business, ensuring the team was up to the challenge of delivering what was promised, and staying ahead of the pack with new ideas.

Dan would travel to Dallas twice a year to meet with our biggest clients and best prospects. Our business grew and the Edelman empire evolved and expanded because of Dan’s energy, curiosity, and focus on high performance, and today his son Richard continues to lead the firm to new heights.

In those face-to-face meetings with clients and prospects, Dan always asked three simple questions that strengthened relationships, uncovered valuable information, and created more opportunity for new assignments, often in ways that allowed the firm to move into new lines of work:

1. “How’s your business?” A great icebreaker that gets people talking about their favorite subject: themselves.

2. “How are we doing for you?” An invitation to assess the firm’s performance and occasionally vent frustrations to the firm’s founder. You can’t fix a problem unless you know about it.

3. “Is there anything you’re working on or thinking about that we might be able to help you with?” When you’re hired for a particular reason, clients can forget or overlook the range of other services you provide.

Asking a few simple questions can help you grow, adapt, and evolve along with your clients and customers.

EVOLVING AT EVERY TURN

Tastes change. Habits evolve. New expectations develop.

The headlines remind us that reading these shifting behavioral sands can be tricky: “Kodak determined to survive,”11 “Newsweek Quits Print,”12 “Ailing BlackBerry to Reduce Work Force and Post Big Loss,”13 “Ron Johnson’s Desperate Broadcasts to J.C. Penney Workers Fell Flat as Company Faltered.”14 The list goes on.

For those leaders, like those at The Container Store, Ernst & Young, Herman Miller, Marriott, Nucor, Sony, and Southwest Airlines, who can navigate change, they look for an opportunity to widen the gap between themselves and the competition.

“The travel habits of our customers have evolved,” says Southwest Airlines CEO Gary Kelly. “That’s why we’ve updated our fleet with newly refreshed cabins … and introduced the sleek, new Boeing 737-800 series aircraft into our fleet for longer flights. We’ve revamped our Rapid Rewards Frequent Flyer program, and we’re equipping Southwest for international service.”15

Smart leaders make big, smart bets and are held accountable for the results those bets produce.

Nucor’s leaders weighed the risk of “the long-term uncertainty that currently exists on the carbon tax issues in Washington” against the opportunity to “achieve our long-term goal of increasing control over our raw materials supply” and built a $750 million 2.5 million tons-per-year iron making facility in St. James Parish, Louisiana. The facility is the proposed first phase of a $3.4 billion investment that will bring 1,250 jobs to Louisiana.16

The plant uses direct reduction technology to convert natural gas and iron ore pellets into high-quality direct reduced iron (DRI) used by Nucor’s steel mills, along with recycled scrap, to produce a variety of high-quality steel products. Nucor said that the “DRI facility was chosen for the first phase of our project …

because it offers a carbon footprint that is one-third of that for the coke oven/blast furnace route for the same volume of product but at less than half the capital cost.”17

Ernst & Young evolved to balance the demanding work it requires of its people to meet client expectations with the reality that hard-working people need time away from the firm to meet other obligations and to recharge their batteries.

Arthur Andersen’s implosion after being indicted by the Justice Department related to its auditing of Enron sent shock waves throughout the business community.

“There was a real scramble in the profession,” says Ernst & Young’s David Alexander, “and the 60- and 70-hour weeks went to 70- and 80-hour weeks. We couldn’t keep up with the volume of work and we started losing a lot of people. So we started a global survey and we started asking our people, ‘What are you looking for?’ and we learned that they wanted more flexibility with their time, they didn’t want an 8-to-5 job. We had already made a commitment to being a ‘people first’ culture, so we developed some of the strongest technology that the profession had ever seen as a way to support our people.”

Ernst & Young also made huge investments in its people, changing everything from maternity leave and working from home to establishing flex time and creating four-day weekends for holidays. The firm encouraged employees to take time off. “We later found that for every day that a person would take off,” says Alexander, “their annual performance ratings improved. By working fewer hours, our employees were happier, their families were happier, and, overall, our employees were more effective.”

Good ideas are copied quickly. Replicating a culture is more difficult. “In the 1980s there were more than 800 companies selling organization knockoffs to The Container Store,” says CEO Kip Tindell. Big companies like Williams-Sonoma had their version; small companies had theirs. Not 800 stores, but 800 companies, some of which had many stores. Fewer than a handful remain.

Having survived those copycats, The Container Store is taking its organizational and storage skills into customers’ homes. The company’s concept of “we’ll bring the store to you,” which it calls ATHOME®, that it’s testing has gotten top marks from customers, so the service is expected to be expanded to other markets.

In 2007, CEO Kip Tindell made a bigger, braver decision in The Container Store’s evolution.

Some of the company’s investors wanted to retire or cash in their chips. At the same time, other companies were looking to recruit The Container Store’s key managers and were offering stock options. “I didn’t have any stock or options [to offer],” Tindell says, “so I set out to find one extremely sophisticated investor, and by sophisticated I mean somebody who understands it’s better to own 50 percent of the dollar than 100 percent of a nickel. That’s hard to find.

“We interviewed more than 100 equity firms,” says Tindell. “We were looking for somebody that would contractually agree to management retaining operational and strategic control. So these guys are buying the majority of the company but they don’t control the company. That’s unusual. They’re giving away about three and a half times the average of the equity not just to a management team but to almost 200 employees.

“I felt this was to be the perfect stakeholder model of conscious capitalism,” says Tindell. “What I was trying to do was keep the exiting shareholders happy, keep the employees happy, keep all of the stakeholders completely happy, and maintain the culture. The bravery was that nobody had ever done the private equity transaction like that before. I remember telling the JP Morgan people, several of whom I knew very well, ‘We’ve got to do this, but I want your very top people involved. I want you to personally run our deal. It will be the smallest deal you’ve worked on in the last 5 or 10 years of your career, but it will be the most joyful.’”

Before it was joyful, it was frightening.

“I’ve never been so stressed out in my life,” says Tindell. “I guess that’s where the bravery came in. But I just thought the whole future of the company depended on getting this thing right, and I thought it could work. And we did it. We’re still with equity firm Leonard Green. We love them, they love us. Things couldn’t be better.”

As you’ve seen before, Tindell is a “win-win-win” guy. That’s what happened with this deal. “Everybody won,” says Tindell. “The employees won because they got this equity. The shareholders won. The bankers won. They say, ‘We’re on the side of the angels.’

“And the employees retained control. We don’t need the private equity firm telling our employees or our merchants what kind of Christmas wrap to buy. How we do things is part of our culture, it’s part of the accountability of how we operate. But I was so unaccustomed to doing billion-dollar private equity transactions that I didn’t know that all this stuff was impossible.”

The relationship worked so well Tindell got his college roommate John Mackey of Whole Foods involved with Leonard Green. “That turned out to be the best investment in Leonard Green’s history,” says Tindell.

Big deals. Small improvements. Calculated risks. Follow-through. Your ability to leverage change, your willingness to evolve, and your conviction to execute your plans will drive your future performance.

All organizations wrestle with accountability in much the same way. Although the scope and complexity may differ from organization to organization, the problems leaders encounter on their journey from Point A to Point B are the same.

High-performing organizations create and sustain a culture of purpose, accountability, and fulfillment that is guided by a set of principles and practices that are simple to say and hard to do.

The key to accountability is bringing together these principles and then acting on them with consistency to sustain a high-performance culture.

You now have a bridge, supported by the Seven Pillars of Accountability, to help you reach Point B.

Where will your bridge take you?