4

CHARACTER COUNTS

Character

Our values are clearly defined and communicated. Values shape

our character: we do what’s right for our customers, employees,

suppliers, and investors … even when it’s difficult.

Nearly all men can stand adversity, but if you want to test a man’s character, give him power.

—Abraham Lincoln

“In the unlikely event of a water evacuation,” the Southwest Airlines flight attendant announced to a plane filled with paying customers, “we’ll be handing out towels and drinks.”

The response by passengers to the flight attendant’s funny reading of dry federal aviation regulations was predictable: everyone laughed, chuckled, or smiled.

Well, almost everyone.

One passenger on board was in the habit of finding fault with everything the airline and its personnel did. She had become known as the Pen Pal at Southwest Airlines’ headquarters because she wrote the company on a regular basis.

Pen Pal didn’t like Southwest’s boarding procedure, not to mention the lack of a first-class section. She didn’t like the absence of meals on flights. And she certainly didn’t like humor related to the serious business of flying. To her, this crack about “drinks and towels” was another example of Southwest’s seemingly lax attitude. She fired off another letter to Southwest.

In the past, Pen Pal’s letters would be answered by Southwest’s terrific customer service folks, but this latest letter stumped them, so they sent it to then-CEO Herb Kelleher. Herb read the accompanying note the customer service folks had attached to the complaint and in less than a minute made up his mind and wrote this response: Dear Mrs. [name], We will miss you. Love, Herb.

Herb’s decision—while quick—was not made lightly. His decision was entirely consistent with the airline’s character. Herb was simply acting on Southwest Airlines’ principles that were galvanized in the early days of the company’s struggle against bigger competitors. These principles are codified in the mission of Southwest Airlines: “Dedication to the highest quality of customer service delivered with a sense of warmth, friendliness, individual pride and company spirit.” This mission is lived out every day by the 46,000 employees in the Southwest Airlines system, and it is part of what gives the airline its unique character. Working hard, having fun, and treating everyone with respect are what the airline calls “The Southwest Way.”

Most mission statements are a dime a dozen. We’ve all seen these impressive declarations that sound good but that are rarely lived out in the behavior of the people in the organization. It’s one thing to say you are committed to a particular belief or behavior; it’s another thing to believe it and live it. Your character, whether organizational or individual, is not what you say you are; it’s how you behave all the time. Words are cheap. Deeds matter. Especially, as Lincoln reminds us, when the stakes are high and your response reveals your character.

The behavior of the flight attendant who made the “drinks and towels” comment was in complete alignment with Southwest’s character that pledges a unique combination of “the highest quality of customer service” delivered with “company spirit.” Southwest Airlines employs a multistep employee screening process that probes to learn as much about a person’s character as it does their technical proficiency. So Herb could trust that the flight attendant and the customer service people had behaved in a manner consistent with the airline’s character. He also knew that his company could likely never do anything to please this customer, therefore he was willing to support his employees and focus his attention on those who flew Southwest precisely because of its spirit.

For a quick glimpse at other ways Southwest’s spirit shows up on a flight, check out this collection of flight attendant announcements I’ve collected as a passenger aboard their flights.

Although many myths, legends, and fables illustrate Southwest Airlines’ one-of-a-kind culture, the Pen Pal story you just read is true. Even if this story was just another tall Texas tale about a maverick airline, you would likely believe the events occurred simply because the conduct of flight attendants, gate agents, and baggage handlers, all the way up to the street-smart founder, is consistent with the behavior Southwest Airlines says it values, encourages, and rewards.

The bigger question is not whether this incident really happened, it is How is your organization’s character revealed when a valued employee disappoints a paying customer?

THE GREAT PARADOX

The Dutch theologian and teacher Desiderius Erasmus wrote in the late 1400s that, “We sow our thoughts, and we reap our actions; we sow our actions, and we reap our habits; we sow our habits, and we reap our characters; we sow our characters, and we reap our destiny.”

When I visited the Nucor plant in Eufaula, Alabama, to meet with Ray Napolitan for the first of my interviews with him, I found a version of Erasmus’s quote on the wall of Ray’s office.

Spend a few minutes with Ray Napolitan and you hear all the right words. Talk to his employees and look at the terrific results that teams led by Ray have produced over the years in four different locations across the United States, and you know that his actions match his words.

Yet that’s not the case in most organizations.

Character counts. Or, rather, we say it does.

In my survey of leaders, when asked, 80 percent of the executives said “we do what’s right for our customers, employees, suppliers, and owners, even when it hurts.” And 76 percent said “we are accountable for our performance and accept responsibility for our mistakes.” Commendable.

But when executives were asked specific questions from the accountability assessment found in the preceding chapter, the good intentions they said existed inside their organizations were practiced with less consistency. For example, the numbers drop to 66 percent who “strongly agree” or “agree” that “our values are easy to understand and simple to remember;” the implication of this statistic is that one person in three—even among an organization’s top leaders—doesn’t fully understand the principles used as a basis for making decisions and driving individual and organizational behavior. The numbers drop further to 58 percent who “strongly agree” or “agree” that “accountability isn’t just top-down; everyone knows they are accountable to one another.” The implication of this statistic is that 4 of every 10 employees view holding people accountable as the responsibility of the supervisor—not the peer. When employees operate in their own world with little sense of shared responsibility with their coworkers for making sure things are done right, on time, and on budget the performance of the organization suffers. Imagine the new levels of performance that can be attained when everyone in the organization—not just management, midlevel executives and supervisors—views holding one another accountable as an essential part of their daily duties.

The paradox of saying one thing and doing another are prevalent in most organizations: the things we say we value—treating others how we want to be treated, quality, innovation, and even accountability—we don’t treat as valuable. We say one thing and do another. Our actions are the outward expression of our character.

In a workshop I was conducting for a successful manufacturing company, I began by asking the participants if they could tell me their corporate values. “Yes,” they answered enthusiastically, “we recently updated them because people couldn’t remember all eight values. We reduced our values to four words so everyone could remember them.”

One of the four values was “integrity” (“integrity,” “respect,” and “honesty” are the trifecta of values because they appear regularly in values statements, so the universal use of these words tends to dilute their impact; even so, if that’s your value, let’s see how it shows up).

“What time was this meeting supposed to start?” I asked the workshop participants. “Nine o’clock,” was the collective response. “What time did we start?” I asked. “Nine fifteen.” “How is that acting with integrity?” “It’s not,” they admitted. So is “integrity” really how things are done at this company, or is it just a word that sounds good?

Starting a meeting late is a small thing, a “wee problem,” but small things become big things and big things can turn into big problems.

The behavior you see is the default culture of your organization. Your culture mirrors your character. Leaders who commit what my friend Mardy Grothe calls “little murders,” such as starting a meeting late, are contributing to a culture that eventually makes accountability all but impossible. We say one thing and do another, showing our organization’s true character is out of alignment with the words we say matter.

What would an impartial visitor to your organization see, hear, and experience? How would the observed behavior align with the behavior you say you want? Is yours a culture that is created and nurtured intentionally, or is yours a culture that occurs by happenstance? Just as you cultivate a garden, you must cultivate a workplace environment where high performance is the expectation.

DO OUR WORDS REFLECT OUR CHARACTER?

“A culture of accountability in any organization starts with its shared values,” says David Alexander, former vice-chair at Ernst & Young and, at the time of our first interview, one of six regional managing partners in the United States. The Ernst & Young global workforce consists of 175,000 men and women, and the “Big Four” firm has enjoyed a reputation as one of the best places to work year after year. As a professional services firm, EY relies on having great people to deliver to its clients the timely, quality work that’s been promised, so you would expect the firm to use a proven system to hire what Alexander calls the “best and brightest” people. “We use our values as a guideline for hiring and for making other decisions,” Alexander told me. EY recruits people who demonstrate integrity, respect, and teaming—the first of the firm’s three values. “We’re very team-oriented, and we want people who can work in a team environment. In order to have effective teaming, you’ve got to have individual integrity and respect for opinion and thoughts.” Second, EY looks for people with a winning attitude. “We characterize our culture as one that’s comprised of people who have the energy, the enthusiasm, and the courage to lead,” says Alexander. “We try to assess people’s leadership attributes early on when we recruit them, and then develop that throughout the course of their career.” We will examine EY’s approach to talent development in Chapter 6.

Courageous leadership and a willingness to make decisions are characteristics that are valued at Nucor. Says Nucor’s Ray Napolitan: “One core Nucor philosophy that was started by Ken Iverson—who laid the foundation for this culture, set the culture, and set the stage for the great profitable growth we’ve had—is, ‘We allow, no we expect, our employees to make decisions. We also know that our employees will make the correct decision about 60 percent of the time. However, we expect you to learn from your mistakes and don’t make the same big mistake twice.’ And while that 40 percent number may seem high, what it means is that if you’re not making mistakes, you’re not running your part of the business like an entrepreneur, like it’s yours. It’s similar to the Vince Lombardi quote that says, ‘If you’re not making mistakes, you’re not trying hard enough.’ Now we definitely expect our people to learn from their mistakes, but because we have hired great people who we trust, our culture is one of empowering our people and encouraging them to think for themselves.”

Trusting, empowering, and encouraging employees are behaviors most bosses claim to support. But when asked directly, only about half of the executives I surveyed (54 percent) agreed with the statement that “we encourage, empower, and reward decision making at every level of our organization.”

Sooner or later, encouraging certain behavior or ignoring other behavior will result in that behavior becoming your organization’s default culture.

So you can say that you “encourage decision making at every level of our organization,” but if what your employees observe is a command-and-control approach to getting things done, after a while they will stop bringing leaders ideas that are never explored (much less implemented), they will stop thinking for themselves, and they will decide that trying to take the initiative is a waste of their time.

Such behavior is entirely predictable—and preventable. In Chapter 8, we examine how one CEO “let go of the reins” and watched his employees become more accountable to one another and, in the process, save their midsize company hundreds of thousands of dollars year after year.

HIRE PEOPLE WHO SHARE YOUR VALUES

Every company and every person will make a mistake. Leaders at the exceptional companies I spoke with minimize those mistakes by hiring people who share their values. This practice is critical for any organization, whether you are a professional services firm, a manufacturer, a retailer, or in distribution-related industries like Southwest Airlines, which moves a lot of planes, luggage, and people on more than 32,000 flights, every day of the year.

“At Southwest we firmly believe in the importance of hiring the right person,” says Elizabeth Bryant. “You cannot train somebody to care about other people or to smile when they see a customer. That’s something you either have or you don’t have. So we first find the people who embody the values that we have at Southwest Airlines. From there we can cultivate them and grow them and train them in the technical skills.”

The values of Southwest Airlines are as simple to remember as they are compelling because they reflect the distinct personality of the airline. It’s unlikely you’ll find these words on the walls or websites of any other company:

![]() Servant’s Heart

Servant’s Heart

![]() Fun-LUVing Attitude

Fun-LUVing Attitude

Bryant describes the warrior spirit as “that ability to work hard and persevere and—no matter what the situation—to see it through.” The servant’s heart, she says, is putting other people before yourself and serving them.

And last, but not least, having fun. Because so much of our time is spent at work, we would all enjoy it more, work harder, and work smarter if we were around people we like and respect. “We’re going to have more colorful debate and dialogue and tackle problems with some energy and some enthusiasm,” says Bryant, “and that’s going to lead to better decision making, which will lead to more commitment to that decision, which will lead to more accountability to that commitment.”

How do you find a fun-loving person with a warrior spirit and a servant’s heart? It takes a lot of work. In 2012, Southwest Airlines received nearly 115,000 résumés and hired only the best 2,500 people. To join this frequent flyer club, you’ve got to be special.

ONE GREAT PERSON

When it comes to people, The Container Store has also done the math.

“One of our Foundation Principles,” founder and CEO Kip Tindell told me, “is ‘one great person equals three good people.’ And if one great person equals three good people, and one good person equals three average people, and one average person equals three lousy people, then one great person equals 27 lousy people. And we’re talking in terms of business productivity. We have chosen to hire great people.”

Great people attract other great people: 36 percent of The Container Store’s 6,000 employees have joined the company through a referral from an existing employee.

At The Container Store, the employee comes first.

“We’re creating a place where people want to get out of bed and come to work in the morning,” says Casey Shilling. “And so the employee comes first. The customer comes second. You don’t hear a lot of retailers say that. You always hear, ‘the customer is always right’ and ‘the customer comes first.’ But we believe that if we take care of our employees and create a workplace that is delightful, then the customer will be taken care of and then the shareholder will benefit.”

To find that great employee, the interviewing process is quite thorough. “We train on interviewing for great employees,” says Shilling. “Asking questions about a candidate’s life experience, asking a candidate to describe a recent experience where they had good service, and asking, ‘What does good service mean to you?’ And once we hire those great employees, accountability is key. During performance reviews, we discuss contributions and opportunities for growth, our Foundation Principles and the employees’ practice of them in their role, and we define SMART goals and an action plan for each employee for the coming year.”

An organization’s foundation is great people who share the values of learning, supporting others, and excelling. “We want the best of the best, so we hire about 3 percent of those who apply with us,” says Shilling. “Our great people tend to weed out the people who are not pulling their weight.”

In an industry where the average annual turnover is greater than 100 percent—imagine replacing your entire workforce year after year—The Container Store’s turnover averages less than 6 percent annually.

Like other exceptional organizations, The Container Store is clear about its purpose and the type of people they want on their team. They look for, hire, and retain people who have a bias for making good things happen.

CODIFY YOUR CHARACTER

The strategy is simple but powerful: Hire the best candidates who align with your values and then pay them accordingly.

Whether you call them values, beliefs, or principles, you can use them every day as a filter for making decisions, including who you hire.

Remember the “Heaven & Hell” exercise from Chapter 1? I’ve made a few changes to enable you to use it with your leadership team to codify the character of your organization (see Appendix).

If one of your values is having fun, ask the person you are interviewing to tell you a joke or funny story. If you place a premium on innovation, search for an understanding of a person’s problem-solving capability. If achieving results matters, explore a time when the person overcame an obstacle.

Use the “Heaven & Hell” exercise to ask interviewees about their character-building experiences. They will be surprised by your approach. And they can’t fake the answers.

When you hire for character as much as skill, you improve accountability because you are in alignment on big things like mission, vision, and values. Your debates and decision making will be centered on practices not principles. And you’ll be rewarded with less turnover, lower recruiting costs, and a higher-than-industry-average productivity rate.

WHO ARE WE?

You’ve got to know yourself before you can be yourself.

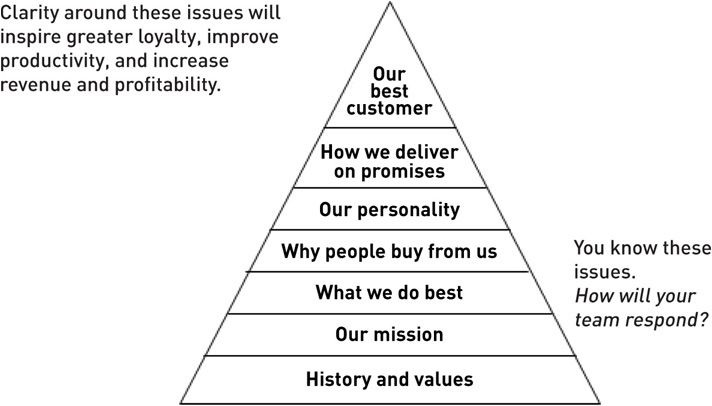

Knowing who you are and your character sets the foundation for your future performance. Your company will evolve as the world around you changes, but what you stand for shouldn’t. When I work with companies to help them improve their performance, one of the first exercises involves completing the model, the Identity Pyramid™, on the following page.

We start at the bottom of the pyramid, the organization’s foundation, and work our way to the top.

You probably have a clear idea about how you would complete each section. What may surprise you as you move forward with this exercise are the differences of opinion that emerge from your team.

A Harvard Business Review article notes that the “dirty little secret” in companies is that “most executives cannot articulate the objective, scope, and advantage of their business in a simple statement. If they can’t, neither can anyone else.”1

I find the same is true of values, which is why I recommend you limit your values to three, four, or five words rather than phrases or sentences that few people can remember. Your values codify your character.

The leadership team of a successful technology company was working through the Identity Pyramid exercise and it came time to review the company’s values. I wanted to hear from the CEO and his leaders to ensure I understood the beliefs we would be using for guidance as we fine-tuned the company’s strategy and operating plan. The company leaders could recall only four of the company’s seven values, so one of the executives pulled up the company website on her tablet and retrieved the other three forgotten values.

These so-called values presented three problems:

1. Phrases fail the test. I’ve seen core values statements that look like the Ten Commandments. Perfectly crafted phrases may look good on paper, but people can’t remember them. Use words, not phrases.

2. Less is more. People cannot remember phrases, and they cannot remember more than five words that characterize your values. Make your values few in number and high in impact. By limiting yourself to three values, you have an excellent likelihood that everybody will understand, remember, and live them. As my friend Ole Carlson says, “The more laws you create, the more outlaws you create.” Three values are excellent, four are good, and five are almost one too many.

3. The real you. Take the opportunity to ensure that your values reflect the characteristics that make your organization different. “Be yourself,” said Oscar Wilde, “everyone else is already taken.”

The case of the technology company whose leaders could not remember their core values caused a bit of a laugh at everyone’s expense. The point was clear: If an organization’s top leaders can’t remember the core values, how do you expect everyone else on your team to remember them?

CHEAP WORDS

Just because your values are easy to remember doesn’t mean they are showing up in the character of your organization.

I was hired by a company to improve organizational and individual performance that was being undermined from top to bottom by a lack of trust and collaboration. Even by the admission of the company’s senior leaders, this dysfunctional organization was succeeding in spite of itself.

When I walked into the lobby for my first meeting, it was hard to miss the framed poster proclaiming the company’s core values. Ironically, “collaboration” was one of four stated values yet they brought me in precisely because leaders were not collaborating with one another in a productive manner.

Character is not what you say, it’s who you are and how you behave. In this company, the behavior was out of whack with the nice words on the wall.

We see plenty of people saying one thing and doing another. In sports, Joe Paterno said that “success without honor is an unseasoned dish,” then he systemically covered up the child-abuse sex scandal at Penn State. As a seven-time Tour de France cycling winner, Lance Armstrong denied for a decade claims he was using performance-enhancing drugs. When the truth came out, sponsors fled, with many saying that Armstrong “no longer aligns with our company’s mission and values.”2

In business, Walmart’s bribery case in Mexico “pitted the company’s much-publicized commitment to the highest moral and ethical standards against its relentless pursuit of growth.” Investigators hired to pursue the bribery allegations “found a paper trail of hundreds of suspect payments totaling more than $24 million” and “recommended that Walmart expand the investigation.” Instead, “Walmart leaders shut it down.”3

Founder Sam Walton, who had danced the hula on Wall Street in 1984 when associates delivered record profits, was probably doing the twist in his grave.4

WORDS MATTER AT THE DELTA COMPANIES

Because The Delta Companies do not manufacture anything, ship anything, or sell products from a brick-and-mortar storefront, CEO Jeff Bowling has been studying, crafting, and perfecting his company’s mission and values for years. How these characteristics show up matters because Bowling’s business, inside and out, is a people business.

Articulating these characteristics was a challenge because Bowling says being clear about purpose puts the people who matter—customers and employees—in charge. “We had to find the right words to describe what was already there,” says Bowling. “Writing some altruistic cliché would have been a snap. But it wouldn’t have been right.”

After two years of reading, soul-searching, and talking with people inside and outside the organization, Bowling and his team codified the company’s character with an elegantly simple statement that was informed by answering this question: What is our reason for existing beyond making money? The answer: “Creating Access for People.”

“This may look simple, and it is when you’re finished,” Bowling told me, “but it was very difficult to nail this idea. Even after we zeroed in on this idea, we had a lot of meetings debating whether the word should be ‘for’ or ‘through.’ Each word matters and we had to get it right.”

It’s a deceptively simply phrase that speaks volumes about the company’s commitment to help people succeed in their career at The Delta Companies, to help the people Delta serves (hospital administrators, physicians, and other providers), and to help people in the communities where The Delta Companies do business.

“The Delta Companies exist to enrich people’s lives,” says Bowling. “Whether it’s the lives of employees and their families, our customers and their staffs and patients, our vendor partners, or our local community. The great part of providing staffing solutions within healthcare is we are creating options, opportunities, and freedoms through access to healthcare that didn’t exist prior to our performance.”

NO MISSION WITHOUT PROFIT

“Profit comes first. People are more important. The paradox recognizes we must first generate profit and people matter. Profit means excess. At The Delta Companies, we have excess in fun, rewards, and the intrinsic good that occurs. And monetary profit. There is no mission without a profit,” according to Bowling.

As CEO, Bowling understands that the companies can be more profitable if employees are engaged and performing at a high level. So The Delta Companies evaluate overall performance as a staffing company by comparing profitability per employee to that of competitors. The Delta Companies enjoy a larger gross profit margin per employee, suggesting that they are outperforming their competition. “Because of that performance,” says Bowling, “we’re able to provide more fun, more rewards, and more giving back.”

The company’s core values have been distilled to two powerful words: Performance and Humanity. Performance is quantified as profit margin, growth rate, Net Promoter score (a measure of customer satisfaction), and productivity per member (employee).

Humanity is quantified as patient access, employee engagement, philanthropy, and fun.

“In order to enrich others, a balanced approach of performance and humanity is required,” Bowling says, and refers to the ancient Chinese who believed in two complementary forces in the universe: yin and yang. One is not better than the other. They are both necessary, and a balance of both is highly desirable.

“For The Delta Companies,” says Bowling, “the yang represents our objective to create a high-performance environment. The yin represents our objective to create a fun, rewarding, and respectful environment. While the yin is intangible and subjective, people know fun when they see it. Energy, passion, creativity, philanthropy, respect, and other positive attributes of the yin are equal in importance to the very tangible and objective yang. “At The Delta Companies,” Bowling reports, “we have zero tolerance for high-performing jerks that suck the yin out of others.”

The Delta Companies hit their financial objectives each year, employees are productive at a rate higher than the industry average, and customer satisfaction level is exceptional with a Net Promoter score averaging 65.1 (in service businesses, world-class scores are 65 and some of the world’s most admired companies have Net Promoter scores in a range of 51–57).

Character counts at The Delta Companies.

FIND YOURSELF IN THE IDENTITY PYRAMID

As you move toward the top of the Identity Pyramid, your perspective should gradually shift from a historical perspective to a current perspective and, ultimately, to a future state. The going gets tougher as everyone takes a crack at providing their take on each section.

Our firm developed a list of “100 critical questions” we would ask when companies engaged us to help them with strategy, performance improvement, and other important activities such as new market entries and products launches. In time, our list of questions grew to number in the hundreds. Here are a few questions corresponding to each of the other sections of the Identity Pyramid to get your juices flowing:

Our mission: Our reason for existing beyond making money.

![]() Why are we in business? What are we trying to accomplish?

Why are we in business? What are we trying to accomplish?

![]() What kind of company are we trying to be?

What kind of company are we trying to be?

![]() What ideas are we fighting for?

What ideas are we fighting for?

![]() If our company did not exist, what would the world be missing?

If our company did not exist, what would the world be missing?

![]() What are we most passionate about today?

What are we most passionate about today?

What we do best: Our core competencies.

![]() How do we deliver value to our customers? Would our customers agree?

How do we deliver value to our customers? Would our customers agree?

![]() Are we financial-driven, sales-driven, operations-driven, or something else? Which of these disciplines puts us in closest touch with the people who use our products or services?

Are we financial-driven, sales-driven, operations-driven, or something else? Which of these disciplines puts us in closest touch with the people who use our products or services?

![]() What are the barriers customers and prospects must overcome to do business with us? What must we do to remove or lower those barriers?

What are the barriers customers and prospects must overcome to do business with us? What must we do to remove or lower those barriers?

![]() Where will our future profitable growth come from?

Where will our future profitable growth come from?

![]() If we are the “gold standard” in our industry, what must we do to strengthen our position? If we are not, what must we do to become the “gold standard”?

If we are the “gold standard” in our industry, what must we do to strengthen our position? If we are not, what must we do to become the “gold standard”?

Why people buy from us: Our competitive advantage.

![]() What causes our customers to select us over our competition?

What causes our customers to select us over our competition?

![]() What memorable experience are we creating with our customers?

What memorable experience are we creating with our customers?

![]() What are our customers’ unmet needs?

What are our customers’ unmet needs?

![]() What is our customers’ greatest pain? What would reducing or eliminating that pain be worth to our customers?

What is our customers’ greatest pain? What would reducing or eliminating that pain be worth to our customers?

![]() Describe the most recent major breakthrough at our company. What has been the impact of that breakthrough?

Describe the most recent major breakthrough at our company. What has been the impact of that breakthrough?

Our personality: How we show up; our culture.

![]() If I could choose just three words to describe our culture, what would those words be? How do those words compare to the ones on our website?

If I could choose just three words to describe our culture, what would those words be? How do those words compare to the ones on our website?

![]() How would our employees describe us? Our customers and prospects?

How would our employees describe us? Our customers and prospects?

![]() If an impartial observer visited our organization, what would that person see, hear, and experience? Are we who we say we are?

If an impartial observer visited our organization, what would that person see, hear, and experience? Are we who we say we are?

![]() How would this observed behavior align with or vary from the behavior we desire as an organization? What is causing this behavior?

How would this observed behavior align with or vary from the behavior we desire as an organization? What is causing this behavior?

![]() What happens when behavior does not match our stated values?

What happens when behavior does not match our stated values?

Our best customer: Customers we love and who love us.

![]() What is it about our best customers that we appreciate the most? What can we do to attract more of them?

What is it about our best customers that we appreciate the most? What can we do to attract more of them?

![]() What is it about our worst or most difficult customers that we dislike the most? What can we do to turn them into great customers? If we can’t convert them, what’s our plan for firing them?

What is it about our worst or most difficult customers that we dislike the most? What can we do to turn them into great customers? If we can’t convert them, what’s our plan for firing them?

![]() What would happen if we increased our focus on our best customers?

What would happen if we increased our focus on our best customers?

![]() Do any surprising situations represent an underserved opportunity?

Do any surprising situations represent an underserved opportunity?

![]() Who uses our product or service in a way that we did not intend for it to be used?

Who uses our product or service in a way that we did not intend for it to be used?

Answering these questions will tell you a lot about your character.

Let’s examine more closely the segment of the Identity Pyramid that reads How we deliver on promises.

THE SCHIZOPHRENIC ORGANIZATION

When leaders are asked, “To whom does your organization make promises?” they generally respond with “customers.”

You know you’re keeping your promises to your customers and clients by measuring revenue growth, retention, repeat business, and referrals. And you occasionally receive comments, calls, and emails telling you that you’ve done a great job. Customer satisfaction surveys such as the Net Promoter score can measure quantitatively how well you’re doing in keeping your promises to customers.

There’s often a “whatever it takes” mindset that comes into play to make sure you’re keeping customers happy. It’s a big part of who you are—your character—to deliver on those promises.

These promises are important, but they are promises made outside the organization.

What about promises being made inside your organization? Why do we treat customers one way and colleagues another? That behavior makes for a schizophrenic organization. The promises being made inside the organization, such as deadlines, commitments, and agreements (both spoken and written) made to one another, are broken every day.

Promises are based on trust. When promises are broken, trust is betrayed and such behavior calls into question whether the trust that existed between two individuals can be restored. Broken promises reveal a character flaw.

When a promise to a customer has been broken or is about to be broken, it’s often because someone broke a promise to a colleague. When this news reaches you, the usual immediate response is that you, one of your star players, or a special group of team members that you can count on gets busy fixing the problem. I call it the Heroic Event. You may call it fire-fighting. Whatever you call it, your job as the leader is to deliver on the promise that’s been made to your customer. It’s in your character to do so.

A sign posted between the men’s and women’s restrooms of a manufacturing company in North Carolina where I was conducting a workshop provides an apt reminder for us to treat our colleagues the way we want to be treated:

In other words, we have met the enemy of underperformance, and it is us.

When assignments are fumbled by your employees, what’s happening? Do they not share your sense of urgency? Your sense of responsibility to others in the organization? Your commitment? Your character? Perhaps not.

When these types of events occur inside your organization, they signal an accountability problem. Such problems make it hard to scale your operation because you’re managing by exception.

Consider these questions:

![]() Has an event like this happened in our organization in the last 30 days?

Has an event like this happened in our organization in the last 30 days?

![]() What was our response?

What was our response?

![]() What was the cost?

What was the cost?

![]() Could the event have been prevented?

Could the event have been prevented?

As you calculate the cost of one of these events, bear in mind that more than money is at stake. Your workflow has been disrupted as you moved this particular problem to the head of the line, effectively jeopardizing the timing of other projects for other customers. Your reputation with your customer has been tarnished. Your reputation with your colleagues hangs in the balance as employees wonder why these problems are allowed to continue and why the people who are part of the problem are still on the team. Reputation—the sixth of the Seven Pillars of Accountability—will be examined further in Chapter 9.

FIND THE ROOT CAUSE OF UNDERPERFORMANCE

As you dig into the problem to learn why it happened, the answer to the fourth question—Could the event have been prevented?—is usually “yes.” Remember the funnel from Chapter 2? It showed two fundamental causes to investigate: People and Processes.

Up to this point, we have examined the idea of character primarily as it relates to the qualities and traits of people. But character can also refer to the qualities and traits of things. So before rushing to blame a person for the problem, reexamine your processes. Is hiring a process or an exercise in individual judgment? Are we hiring the right people, not just for a job, but for our culture? Consider the character of your other processes, including these three:

1. Workflow. What systems are in place to replicate success? Do those systems reflect the way work really gets done? What steps can be added, deleted, or modified to improve efficiency?

2. Tools, training, and development. Do people have the tools they need to be effective? Has the organization provided training and development to help people do their jobs to the best of their abilities? How do we test to ensure people have the tools and training they need? How do we develop soft skills, such as leadership, judgment, and problem solving?

3. Communications. Were the expectations of the job clear? Were the expectations related to individual performance clear? Were the direction and feedback provided consistent?

We look more closely at these issues in Chapters 5 and 6.

When you turn to the People component of the Heroic Event, consider the role character plays in these three facets of the human condition:

1. Skill. Did the person who made the mistake have the skill to perform the job he or she was asked to do?

2. Will. Did the person who made the mistake have a passion for what they’re doing or were they just going through the motions? Do they want to improve?

3. Fear. Did the person recognize that something wasn’t right, but was fearful of bringing a question or problem to the attention of his or her supervisor? If so, was it out of fear because the person believed he or she would be asked to add solving this problem to the long list of tasks already being worked on? Or was the person afraid of a “shoot the messenger” syndrome? Whose character is in question?

Over time, each person in your organization creates a bias about his or her character. For one person, the bias may be one of commitment and dependability. For another, the bias may be one of empty promises and always falling short. In each case, the person’s behavior has earned the particular bias.

It’s true that top performers may not be fearful of speaking up about problems. But stars who see their colleagues drop the ball and get away with it or who watch their suggestions for improvement fall on deaf ears will decide it’s not worth giving their best and may, in the end, decide to jump ship.

The sum of this behavior is your character, and it’s on display every day in your organization.

It’s your culture. The words you choose to describe your values are important. You have chosen these words to describe your organization’s character. Your promises are the actions that speak louder than your words. Are they in alignment?

In high-performing organizations, accountability is a side-to-side process. But accountability starts at the top and is shaped by the character of an organization’s leaders.