9

WALKING THE TALK

Reputation

We watch results to reward achievement and address underperformance, earning us a reputation—internally and externally—as an organization whose behavior matches our values.

Many a man’s reputation would not know his character if they met on the street.

—Elbert Hubbard

The April 10, 2010, explosion of the Macondo oil well off the coast of Louisiana gutted the Deepwater Horizon, resulted in the deaths of 11 workers, and caused the worst offshore oil spill in U.S. history.

Though British Petroleum has since settled the criminal lawsuit with the U.S. government for $4.5 billion, the Environmental Protection Agency temporarily blocked the company from obtaining new contracts with the federal government, citing a “lack of business integrity.” When the suspension was announced, it was expected to be “short-lived … leaving no discernible effect on BP’s drilling or development pipelines.”1

Here’s the rub: On one hand, a tragedy of epic proportions caused loss of life, widespread damage to a coastal ecosystem and its wildlife, and billions of dollars in damages. BP’s chairman was ousted by his board within weeks of the explosion. On the other hand, the event is expected to have “no discernible effect” on BP’s operations and future earnings.

Was BP’s reputation damaged? What about the personal reputations of those associated with this disaster? What is the impact of a damaged reputation?

A study published in 2000 concluded that “a 10 percent change in CEO reputation is expected to result in a 24 percent [negative] change in a company’s market capitalization.”2

A different study published in 2012 reached a similar conclusion, reporting “an 80 percent chance of a company losing at least 20 percent of its value (over and above the market) in any single month, in a given five-year period,” and “in each case, the value loss was sustained.”3

Warren Buffett once said, “We can afford to lose money—even a lot of money. We cannot afford to lose reputation—even a shred of reputation.”4

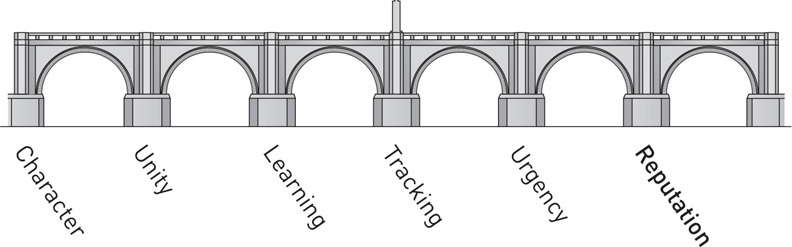

Reputation, the sixth pillar of the Pillars of Accountability, is at risk as your colleagues watch to see how you handle adversity, conflict, and character flaws.

The Character Pillar and Reputation Pillar are linked. Character is who you are. Reputation is how others see your character being lived out. If your character and reputation “met on the street” would they know each other?

REPUTATION STARTS INSIDE

Of the executives I surveyed, 84 percent say, “We know that a favorable reputation is dependent on our behavior matching our values.”

Just as most leaders answer “customers” when asked “to whom does your organization make promises?” most leaders’ first thought when asked about “reputation” is to consider it as something that occurs outside the organization.

Although technically true, this assessment is only half the equation. Your reputation as a leader is also being formed by your ability or inability to live up to your promises inside your organization.

Are you living your values? Are you walking your talk?

Seventy-eight percent of the executives surveyed “strongly agree” or “agree” that “we recognize that failure to address under-performance costs us personal and institutional credibility that damages our reputation.” And 60 percent of the executives surveyed “strongly agree” or “agree” that “we reward results, not activities.”

Yet only 47 percent, about one in two leaders, “are not afraid of respectful conflict so we will initiate a tough conversation.” Leaders of these companies are focused on getting results, but their responses indicate that holding people accountable is difficult.

The principles, practices, tools, and techniques in the preceding chapters help remove, or at least mitigate significantly, the subjectivity and emotion that constitute the reasons most leaders delay having straightforward conversations about poor performance, whether it’s a missed deadline or delivering terrific results in a manner inconsistent with the organization’s values.

A delay in addressing underperformance signals to your employees that you are either oblivious to the problem or afraid to confront the issue. Neither choice inspires confidence, and such behavior diminishes your credibility.

Leaders tell me that conversations about performance problems are delayed or altogether avoided for three primary reasons:

![]() “I want to be liked.” The leader is concerned that having the conversation will harm their relationship with the under-performer and also anticipates that the conversation will be tougher on them as they initiate the conversation than on the underperformer. The opposite is generally true: The underperformer is often relieved the conversation is happening because they have enough self-awareness to know they’re not meeting expectations. When a leader fails to confront underperformance, that leader’s reputation within the organization takes a hit because it’s disrespectful to top performers, plus those employees know who’s performing and who isn’t.

“I want to be liked.” The leader is concerned that having the conversation will harm their relationship with the under-performer and also anticipates that the conversation will be tougher on them as they initiate the conversation than on the underperformer. The opposite is generally true: The underperformer is often relieved the conversation is happening because they have enough self-awareness to know they’re not meeting expectations. When a leader fails to confront underperformance, that leader’s reputation within the organization takes a hit because it’s disrespectful to top performers, plus those employees know who’s performing and who isn’t.

![]() “Their poor performance is temporary.” Underperformers seldom improve without prompting. A leader who believes otherwise has entered the final phase of the three phases of employment: faith, hope, and charity. You have hired on faith, you hope the person performs the work they’ve been hired to do, and you keep them on charity (i.e., your payroll) long after they have shown they are unable or unwilling to meet their performance expectations.

“Their poor performance is temporary.” Underperformers seldom improve without prompting. A leader who believes otherwise has entered the final phase of the three phases of employment: faith, hope, and charity. You have hired on faith, you hope the person performs the work they’ve been hired to do, and you keep them on charity (i.e., your payroll) long after they have shown they are unable or unwilling to meet their performance expectations.

![]() “That’s just how he is, but look at his results!” Leaders can be held hostage by top-performing employees who are delivering great results at the expense of their peers, their supervisor, or perhaps even their company. Who’s in charge, you or a renegade employee? What values really matter?

“That’s just how he is, but look at his results!” Leaders can be held hostage by top-performing employees who are delivering great results at the expense of their peers, their supervisor, or perhaps even their company. Who’s in charge, you or a renegade employee? What values really matter?

Addressing a performance issue is more difficult and more emotionally gut-wrenching if the up-front contract has not been established. Without that contract, the result is ambiguity instead of clarity around the performance expectations, tracking, and the if/then component that spells out rewards when expectations are met and penalties when they are not.

THE CULTURE CRASHERS

In Chapter 2, we said that some members of your team will be excited about the journey to Point B, but others—usually the vast majority—will take more of a wait-and-see approach. And a third group of employees may resent the changes you are asking of them and may try to undermine efforts to reach Point B.

Employees in this third category are culture crashers.

Party crashers aren’t new. Every year, people make headlines by strolling uninvited into private parties.

The uncomfortable reality is that every business has its crashers. The irony, of course, is that unlike a party crasher, the people crashing your culture have been invited into your organization. These culture crashers survived a hiring process and managed to beat the system.

Now they’re hanging around your organization wreaking havoc with the high-performance culture you’re building and nurturing.

It’s hard enough battling the world outside your organization without having to fight discourtesy, turf wars, and inefficiency on the inside. So if people in your office show behavior that does not match the values you say are important, your credibility as a leader is at risk and your organization’s performance is suffering.

Are any of these characters crashing your culture? Do you recognize yourself?

![]() The Sugar-Coater. Willing to address 90 percent of what needs to be said but avoids, downplays, or glosses over the difficult 10 percent that can drive positive change. Unwilling or unable to talk about tough issues that must be addressed to improve organizational or individual performance.

The Sugar-Coater. Willing to address 90 percent of what needs to be said but avoids, downplays, or glosses over the difficult 10 percent that can drive positive change. Unwilling or unable to talk about tough issues that must be addressed to improve organizational or individual performance.

![]() The Control Freak. Doesn’t trust anyone or anything so she can’t let go and, as a result, is always doing someone else’s job … except her own. She erects barriers to her colleagues’ initiative.

The Control Freak. Doesn’t trust anyone or anything so she can’t let go and, as a result, is always doing someone else’s job … except her own. She erects barriers to her colleagues’ initiative.

![]() The Monday Morning Quarterback. Armed with 20/20 hindsight, this second-guesser says little of substance before a decision is made, and then spouts off afterward about what he would have done differently.

The Monday Morning Quarterback. Armed with 20/20 hindsight, this second-guesser says little of substance before a decision is made, and then spouts off afterward about what he would have done differently.

![]() The Gossip. Spreads rumors and loves to dissect problems while rarely suggesting a solution. Avoids speaking directly to the people who are the subject of her rants as well as to the people who can fix things.

The Gossip. Spreads rumors and loves to dissect problems while rarely suggesting a solution. Avoids speaking directly to the people who are the subject of her rants as well as to the people who can fix things.

![]() The Dictator (aka Emperor, no clothes). Known to banish from plum assignments and key meetings those who answer hard questions truthfully. Also regularly shoots messengers who observe and report problems.

The Dictator (aka Emperor, no clothes). Known to banish from plum assignments and key meetings those who answer hard questions truthfully. Also regularly shoots messengers who observe and report problems.

![]() The Know-It-All. As the unofficial expert on everything, he has rarely met an idea of his that wasn’t the best solution. Tone deaf to other possibilities.

The Know-It-All. As the unofficial expert on everything, he has rarely met an idea of his that wasn’t the best solution. Tone deaf to other possibilities.

![]() The Fire Fighter. Rushes in to save the day but cannot or will not prevent the problem. Occasionally lights fires herself in order to play the hero.

The Fire Fighter. Rushes in to save the day but cannot or will not prevent the problem. Occasionally lights fires herself in order to play the hero.

![]() The Cover-Up Artist. Dodges responsibility by deflecting blame to others. First in line, however, to take credit, regardless of whether he was responsible for success.

The Cover-Up Artist. Dodges responsibility by deflecting blame to others. First in line, however, to take credit, regardless of whether he was responsible for success.

![]() The Joker. Loves to poke fun at principles, policies, projects, and people. Everything’s funny to this one, except herself, which she takes far too seriously. The Joker’s deadlier cousin is The Assassin, who’s more vicious in his ruthless approach to dispatching anyone or anything not to his liking.

The Joker. Loves to poke fun at principles, policies, projects, and people. Everything’s funny to this one, except herself, which she takes far too seriously. The Joker’s deadlier cousin is The Assassin, who’s more vicious in his ruthless approach to dispatching anyone or anything not to his liking.

![]() The Quitter. Surrenders at the first sign of difficulty. Is tired of the fight, but not the paycheck.

The Quitter. Surrenders at the first sign of difficulty. Is tired of the fight, but not the paycheck.

![]() The Sandbagger. Protects budgets, goals, and deadlines with plenty of cushion to ensure underwhelming results. Has never seen a stretch goal she couldn’t shorten.

The Sandbagger. Protects budgets, goals, and deadlines with plenty of cushion to ensure underwhelming results. Has never seen a stretch goal she couldn’t shorten.

![]() The Empire-Builder. More interested in how many people report to him than developing talent, fixing problems, and getting results.

The Empire-Builder. More interested in how many people report to him than developing talent, fixing problems, and getting results.

As a leader, you get the behavior you tolerate. So like a lot of tough decisions, deciding how to handle a culture crasher in your organization may be a decision that falls to you.

You have two choices.

You live with the unwanted behavior. If so, what is the cost to your personal reputation as your colleagues see you let some people get away with behavior that’s counter to your values? What are these culture crashers costing your firm’s morale? What is the cost to your organization’s performance as distractions multiply, deadlines pass, and productivity drops? It is hard for most culture crashers to change their behavior. It doesn’t mean they can’t, simply that it is more likely they won’t.

Your second choice is asking them to leave. Doing so isn’t always as easy as you might think. That’s what Rob and Ed Grand-Lienard learned.

A COMMITMENT TO CULTURE

Bob Grand-Lienard started Special Products & Manufacturing out of his garage in 1963, and today his two sons and 240 employees deliver electromechanical assembly, precision metal fabrication, machining, welding, and powder coating to customers such as Alcatel-Lucent, Baker Hughes, Caterpillar, and GE from a 140,000 square-foot state-of-the-art facility 30 miles east of Dallas.

When Rob, CEO, and Ed, COO, joined the company in the early 1980s, getting things done was simple. “We did everything ourselves,” Ed told me, “and we were in charge of the workflow, so you had ultimate accountability over yourself as well as all the people. With only three dozen employees, it was easy.”

“We knew how to manage processes and people when we were that size,” adds Rob. “Today, it’s the classic difference between managing and leading. As we grew, we added people and our decisions became bigger. They weren’t $50,000 decisions, they were $500,000 decisions.”

By 2009, SPM’s growth to 148 employees prompted the brothers’ realization that the company was a boat without a rudder. “We were allowing the company to be blown around,” says Rob, “and we realized we needed a vision. I heard some people define their vision by dollars or by size, and I thought about that and realized those things don’t define a vision.”

Yes, the brothers wanted to grow. It took 48 years for the company their father started to become a $20 million company, and Rob and Ed figured they could double that in five years, and then double it again. But when the brothers talked about where they wanted this company to be in 10 years the conversation turned to becoming the best contract manufacturing partner for Fortune 500–type customers.

“When Rob and I developed that vision,” says Ed, “we thought we were committing to changing our processes, and we’ve certainly improved our processes. But what we were really committing to was changing our culture.”

SPM had grown using a command-and-control approach typical for a manufacturing firm. The first big change occurred in 2009 when the brothers brought 30 shop floor employees into a room and asked, “Do we have any problems between the time a customer calls us and when the money’s in the bank?” No one spoke. “They didn’t trust that we really wanted to know,” remembers Rob, “but we kept fishing and finally someone was brave enough to speak, and the first issue came out. And then the issues kept coming. After three hours we had sticky notes all over the wall, and we saw the excitement in their eyes. I turned to Ed and said, ‘If we get everybody engaged like this and believing in themselves like this, we can accomplish great things.’”

But they encountered two culture crashers who didn’t like what these changes meant for them.

THE DICTATOR

The Dictator was hired 38 years earlier by the brothers’ father, and Rob and Ed had grown up with him as their mentor. The Dictator had flourished in the command-and-control environment because he was in command. He had risen to oversee all plant floor operations.

After the meeting with their 30 employees, Rob and Ed started walking the shop floor more regularly. They initiated a practice of inviting small groups of employees to monthly lunches in SPM’s conference room to ask employees for their input and learn what barriers were making it difficult for them to perform their work.

“As people realized that we really did want to hear what they had to say,” says Rob, “and as we listened to people who reported to [The Dictator], it became apparent he was one of the barriers. He was telling us he was changing and moving in the direction we had charted for the company, but his behavior didn’t match his words. He wanted to be the big man. Talking with him didn’t help. Coaching didn’t work. We came to the realization that every job he had ever held had passed him by. We also concluded that we were giving every appearance of playing favorites, that we were talking out of both sides of our mouth when it came to accountability.”

With The Dictator, the behind-the-scenes conversations were uncomfortable. The brothers were talking to a man who had raised them in the business. They spelled out the expectations and the consequences. And when the expectations were still not met, Rob and Ed Grand-Lienard were faced with a reputation-defining decision: all employees—even those they loved like a father—must be held to the same standards. Leadership is not doing what’s easy or popular, it’s doing what’s right and necessary. It was time for The Dictator to go.

“We had to be sure,” says Ed, “and we needed to be fair to a guy who had been here for nearly 40 years. So after 18 months of empty promises by him, I woke up one day and said, ‘Today’s the day.’ He was holding his people back, and he was holding us back. He was costing Rob and me credibility. When we told him we were separating, he didn’t want to leave but he wasn’t surprised.” A generous severance package was offered and accepted.

Despite the differences and disappointments, The Dictator’s exit was handled with dignity. Rob and Ed held an all-employee luncheon in the plant to celebrate and honor The Dictator’s many years of service, concluding the ceremony by handing him the keys to a new pickup truck.

THE COVER-UP ARTIST

The Cover-Up Artist, on the other hand, was a similar story with a different ending. For years she had been a key part of SPM’s front office team. But as the company grew and performance expectations were raised, it became clear she didn’t have the skill or the will to move forward with the changes under way at SPM.

After more than a year of coaching and being placed on two separate performance improvement plans for missing deadlines and being less than supportive of the changes that were occurring, The Cover-Up Artist was caught in what Rob Grand-Lienard calls “a blatant disregard for one of our core values. Her supervisor came to us with a recommendation to terminate her that very day, and we supported that decision.”

“Some people just don’t want to be part of what we’re building,” says Ed, “and some, when they finally realized that we would hold them accountable for their performance, decided to leave. But 80 percent of the employees who were here four years ago and who were watching our commitment to changing the culture now see that accountability is a good thing. Accountability creates a stable work environment where we trust each other and help each other improve. The big lesson to me in all of this is that I must hold myself accountable to clearly communicate expectations to my direct reports and then make sure they communicate their expectations to the people who work for them.”

“All employees in the organization have to know what’s expected of them,” echoes Rob. “When they go home at night and sit at the dinner table and their spouse says, ‘Honey, did you have a good day?’ they must be able to say, ‘I had a great day because I hit all the results I was asked to hit.’ If we don’t give them the specifics, then they can’t be held accountable.”

Lack of accountability, says Rob, “is the time you lose getting to your goal.”

Rob and Ed Grand-Lienard have doubled their business in the last four years and along the way they have earned a reputation—internally and externally—of setting high standards, making tough choices, and changing the command-and-control culture to a workplace that walks the talk of one of SPM’s core values: Teamwork.

ACCOUNTABILITY AT MARRIOTT

Leaders of successful organizations set the performance bar high and believe that doing so drives high performance.

Marriott is clear about the performance it expects from its associates. And its associates are clear about what they can expect from Marriott.

“Our company,” says Bill Minnock, “constantly reinforces the values and principles of our founder, J. W. Marriott, Sr.: ‘If you take great care of your employees, they’ll take good care of the guests and the guests will return again and again.’ Our number one value is ‘Put people first.’ And Bill Marriott says it all the time that treating each other well is central to creating a culture where we all treat guests well. We can all quote this stuff.”

Those values translate into performance for Marriott, and may explain why half of the company’s general managers were once hourly employees. The average length of tenure for Marriott GMs is 25 years.

At the property level, performance measurements are clearer, the increments are smaller, and timing is faster.

“If you’re a desk clerk and you’re upsetting the customers or you’re a housekeeper and you’re not cleaning your rooms, we go quickly to progressive discipline,” says Minnock, formerly GM of Marriott’s Bethesda, Maryland, hotel. “And progressive discipline can occur in 30, 60, or 90 days depending on the longevity with the company and the severity of your nonperformance.”

Marriott is focused on a balanced scorecard: Satisfy the customer, satisfy the associate, drive revenues, make money, and be a good member of the community.

“The accountability model is a little more difficult in a headquarters environment,” says Minnock, “because it’s a little less clear about who is really driving something, and that’s definitely one of the challenges that all businesses face.

“When you have a team of 20 or 30 people working on something that goes well, everybody’s trying to take credit. If it doesn’t go well, whose fault is it? Sometimes it’s hard to really pinpoint, but we work at it.”

No organization bats a thousand when it comes to achieving high performance, but successful companies are better than most at identifying underperformers, balancing “humanity and performance” as they coach these underperformers, and then moving them out if the employee can’t or won’t improve.

“Once an underperformance issue is identified,” says Minnock, “you can generally put them into two buckets of folks. In one bucket, you have those people who have good self-actualization and, in the other bucket, you have those who don’t. Those who do generally can see that they’re in a job where they’re not performing and they understand that they need to find another place. It’s not fun to have those difficult conversations, but it’s your job. You’ve got to say, ‘This is not about you being a bad person. It’s about this not being the right fit.’ When you have that difficult conversation, it’s often almost a relief to those people who know they’re not performing well.

“For those who don’t see how they’re performing,” says Minnock, “you’ve got to have clear conversations about how they are performing. Sometimes, no matter how many times you tell them, there’s denial, and for those, it’s a complete surprise. But you’ve still just got to do it, and we move them out of the organization.”

BEST JOB THEY’VE EVER HAD

Rick Kimbrell has an entrepreneur’s blood flowing through his veins.

He worked with his father, mother, and brother in a sanitation business they owned that was purchased in 2000 by DeLaval, Sweden’s leading producer of dairy and farming machinery.

Kimbrell worked through his earn-out, cashed in his chips, and then joined another large sanitation company where he was the top sales producer. Delivering the performance he had sold his customers was an issue for this company. “Of the 30 people I was working with,” Kimbrell told me, “12 of them needed to go, but I didn’t have the authority to take that action.”

When Kimbrell saw that nothing would change, he launched StartKleen in 2009.

StartKleen’s work is dirty, smelly, and back-breaking. Kimbrell’s company cleans meat production facilities to ensure these plants meet USDA and OSHA requirements. Most of the work is performed at night; Kimbrell’s supervisors release the plant back to their customers around 5:30 a.m. after meeting strict quality assurance metrics.

“I knew when I started this company,” says Kimbrell, “that I only wanted to work with great people who would pour themselves into their daily work and be passionate about it. From the front office to the employee on the plant floor, we all love working with each other and we respect each other.”

In just four years, StartKleen has achieved an annual revenue run-rate of $24 million servicing blue chip customers such as Hormel, Kraft, Sysco, Bob Evans Foods, Ben E. Keith, and Tyson.

Kimbrell’s team of 580 employees has earned a reputation as the best in the business for helping manufacturers reduce their labor costs, decrease water consumption, and avoid the red-tape and high cost of government-mandated shutdowns.

When you meet Rick Kimbrell, you know that his word is his bond. His customers know it. His employees know it. He expects great things of himself and those who work for him. He holds them accountable to those standards, and those who don’t measure up exit the company quickly. Those who perform share the profits, praise, and pride in a job well done.

Even with his employees scattered across so many locations, the StartKleen culture is shaped by Rick Kimbrell’s passion for his work, his commitment to deliver on what he promises, and his fairness in dealing with his employees.

“My job,” says Kimbrell, “is to make this the best job my employees have ever had.”

CHARACTER TESTED, REPUTATION SOLIDIFIED

Tough times, it’s said, doesn’t build character. It reveals it.

When the Great Recession was at its worst, Herman Miller was forced to furlough people because customers were not buying the office furniture and home furnishing products the Michigan-based company designs and manufactures.

“Leadership worked hard to minimize the impact on our employees where possible,” says Tony Cortese. “We shut down all operations every other Friday. All employees worked and were paid for nine out of ten days every two weeks, which meant a 10 percent cut in pay. The executive leadership team took even larger cuts in pay, including the CEO, who took a 20 percent cut in pay. We did this for approximately one year before restoring everyone to their normal work schedule and pay at 100 percent.”

During that year, Herman Miller developed a quarterly incentive plan that gave employees the opportunity to earn back dollars.

At the end of that year, employees earned back half of the 10 percent pay cut. “This plan,” Cortese says, “was well received by our employees. They understood what we were doing and why. Communication was critical.”

Two years later, the company reported net sales of $1.77 billion, a year-over-year increase of 2.9 percent, and noted the company “achieved quarterly sales, earnings, and cash flow generation at or near their highest levels in more than four years.”5

Loyalty, like accountability, is a two-way street, so as the market recovered and the company’s production increased, Herman Miller brought back “most all of the manufacturing-based employees,” says Cortese.

As hiring resumed at Herman Miller, candidates brought tough questions for the manufacturer. “A common question for candidates to ask,” says Cortese, “is, ‘Herman Miller’s been through a tough time here and I know you’ve done some downsizing. Talk to me about what’s going on here and how you’re handling that. How do employees feel about that? What are my future prospects given what the economy has done within this industry?’ We get questions about diversity and the environment. People are asking questions today much differently than I would’ve asked years ago when I was interviewing,” says Cortese. “People are checking us out and when they come in to explore a job possibility, it’s becoming much more of a dialogue as opposed to just a one-sided panel or a gauntlet. And that means that employers need to be prepared with frank and candid answers on these issues.”

When The Container Store cut benefits rather than lay off any of its 6,000 employees, the company’s reputation as a straight-talking and empathetic employer helped it navigate the tough times.

“We’re not going to act like we’re not affected by this recession,” says Casey Shilling, “so we told our employees what was going on. ‘You see the sales every day, you know what’s going on. This is why we’re making these decisions.’ We hire smart people who are invested in the business. People are not dumb. They can see right through anything that is less than the truth. So I would say to a leader who tries to sugarcoat difficult news, ‘You can do that, but people will not follow you. They will not feel that you care about them.’ They would rather hear the real scoop and understand how we’re going to get through it together than to hear something that ends up not being the truth.”

THE HEROIC EVENT REVISITED

Why do good projects go bad? Often because of a bad culture.

In toxic cultures, blaming colleagues is more likely to occur than accepting responsibility and supporting one another. The president of a family-owned and -operated business once told me, “We’re a murder mystery waiting for the first act to begin.” You can cut the tension in that office with a knife, and I’m confident the cynic’s six phases of a project are alive and well in that company:

1. Enthusiasm

2. Disillusionment

3. Panic and hysteria

4. Search for the guilty

5. Punishment of the innocent

6. Praise for the nonparticipants

Let’s return to the Heroic Event from Chapter 4. This event occurs when a promise to a customer has been broken or is about to be broken because one colleague failed to keep his or her commitment to another colleague. Someone—perhaps you—will step in and save the day. As the project is rescued, timing, workflow, and cost issues need to be addressed internally, and your people will wonder how much longer the underperformer will be allowed to get away with this disruptive behavior.

Externally, you have broken your commitment to your customer. Your reputation with your customer is tarnished from missing a deadline or delivering poor service or a shoddy product.

So you get on the phone with your customer and make another promise. This time we’ll get it right, you say. Whether you get another chance depends on your reputation with your customer.

What happens next is another reputation-defining moment for you as a leader. As you “search for the guilty,” you must decide what role you played in the event. Is the process broken? Were you unclear in setting expectations? Did you make it difficult for someone to come forward and warn you of the impending disaster?

If the problem lies with the individual, you must decide how you will address that person’s performance.

“The hardest thing about accountability,” says Ernst & Young’s David Alexander, “is consistent performance evaluation. If you are inconsistent with how you’re communicating expectations or you’re inconsistent in evaluating performance, then it will tear down the fabric of your culture.”

In other words, if you have accountability in four out of five instances—business units, departments, or employees—you have it in none.

CONFRONTING UNDERPERFORMANCE

Just as consequences have come to be viewed as unfavorable when in fact a consequence can be favorable or unfavorable, the idea of confronting an issue has taken on a negative meaning.

The origin of the word confront is two Latin words—con (originally com), meaning “together,” and frontem, meaning “forehead.” Confront is a neutral word meaning “to stand in front of.”

So when you confront an issue, you are simply bringing that issue front and center to be addressed. You are attempting to get at the truth. Perhaps the negative connotation occurs because the longer we wait to confront a small problem, the bigger the problem can become. We tend to be mad at ourselves for not having set clear expectations and frustrated by our unwillingness to confront the issue, then we have these conversations in our head and not with the underperformer. One-person conversations aren’t useful.

Neither is delaying the conversation. Bad news, unlike fine wine, does not get better with age.

For that reason, as soon as you see a problem developing, it’s a good practice to say something about it. Doing so takes less energy than waiting. And, as we discussed in Chapter 7, you are more likely to have a range of options to address a budding mistake or fast-approaching deadline.

“First, if we don’t confront substandard performance,” says Nucor’s Ray Napolitan, “then we are not being fair to the rest of our teammates in our division and in our corporation. So I’m not doing my job if I don’t hold everyone accountable, including myself, and especially myself. Second, your people know who the performers are and who the performers aren’t. If you as a leader do not address the substandard performance, your respect in their eyes will diminish. You’ll lose credibility, you’ll lose respect, and overall the top performers may decide that it’s not worth giving that extra.”

Brian Lacey of Clark Builders asked a simple question to confront underperformance he observed two levels below his position in the organization.

“I had a senior field guy who had to manage a personality issue on site,” says Lacey, “and my take on it was that the individual was probably not best suited for the company. Yes, I can walk in there and dictate that this guy’s got to go and potentially disrupt the friendship and maybe his respect for me.

“I struggled with how to approach this. And I went out there and said, ‘You know, I have to allow you to be responsible. That’s what I ask you to do, and you make decisions and you manage people. I’m going to ask—when you make the decision relative to this individual—would you write it down on a memo and say “To whom it may concern” and post it in the lunchroom for every one of the shareholders to read and say, “Yes, he’s representing our interest well”?’ And I said, ‘I’ll let you think about that.’

“The next day he called me back and said he terminated the guy. He realized that he was being called upon to make decisions that affect a lot of people’s interests, and he said, ‘I’m hoping that everybody else out there is looking after me as well.’ It’s interesting what happens when you empower people to make those decisions as opposed to dictate them.”

SEVEN QUESTIONS ABOUT UNDERPERFORMANCE

When you see material changes in someone’s performance, whether it’s a top performer or an average performer, you will need to figure out what’s happening in their life to account for the drop-off in their performance.

What signs have you missed along the way?

If you have been having one-to-one sessions where you regularly allocate a minimum of an hour of time each month to talk—not hallway conversations, not in staff meetings, and not even about the latest project they’re leading—you may have picked up on these signs.

As an executive coach, I find that even the most successful leaders need someone to talk to, which is true inside your organization as well. Carving out time to meet with those who report to you will save you countless hours and dollars down the road. The form I use as a guideline for these discussions is in the Appendix, page 275.

Communication helps, but it cannot explain away poor performance. As you consider your next steps with an underperformer, answer seven questions:

1. How important is this person to the organization?

2. Is this person capable of doing what is required to get his or her performance back on track?

3. Is this person willing to do what is required to get his or her performance back on track?

4. How much of my time am I willing to invest in this person to help get his or her performance back on track?

5. How much of the organization’s time can we invest as this person works to get his or her performance back on track?

6. What’s my backup plan if this person is unable or unwilling to change and meet my performance expectations?

7. What’s my commitment to executing the if/then contract?

Get clarity around these questions.

SKILL OR WILL?

“When a high-performing person stops being high-performing,” says Southwest Airlines’ Elizabeth Bryant, “I’m consistent every time. The first thing I do and that I expect all of our leaders to do is to sit down with that employee and find out what’s going on with that person.

“Chances are there’s something happening. So seek to understand what that is. If it’s a work situation, can we remedy it? If it’s a personal situation, do we need to take a little time off and give that back to you? You can manage that and then come back. Everything comes down to the ability to sit down and have an honest, thoughtful, transparent, no-agenda conversation.”

It’s up to the leader to have those conversations so the employee knows where he or she stands. Leaders must recognize that mistakes happen. Underperformance is a pattern. The conversation with an employee who’s consistently not meeting expectations is different from one with an employee who’s made a mistake.

“At Southwest Airlines,” says Bryant, “we sit down and say, ‘I understand why you made that decision’—especially if you leaned toward the customer or the employee, we’re going to forgive almost anything—‘but it’s a mistake.’ So I’m going to encourage the person to get back up and try again.”

Leaders who fail to tell an employee where that person stands are doing the employee and their organization a tremendous disservice.

“If low performers are comfortable in their role,” says Bryant, “they’re never going to make a change. They’re never going to improve. Typically, an employee doesn’t want to be a low-performing employee. Something isn’t working. Is it a will issue or is it a skill issue? If it’s a skill issue, that’s what you address. If it’s a will issue, that’s a pretty easy decision to make and most of the time it’s moving them out of the organization.”

Determining your course of action with an employee comes down to caring about the person and asking lots of questions.

THE ICEBERG CONVERSATION

Less than 20 percent of an iceberg is above the water’s surface and visible.

To address underperformance, you must figure out what’s happening below the surface, the part you may not be able to see. What is the underperformer thinking? Feeling? Has that person’s beliefs changed? How aware is the person that his or her performance has gone south?

“If you care enough about your employees to really sit down and truly know them,” says Bryant, “then there aren’t too many mysteries. You can figure it out. It’s not even about length of time in the relationship; it’s about the quality of the relationship.”

When Bryant first moved into her current position, she went from leading a team of a couple of dozen people to a team of about 200 people. During the first three months in this role she met one-on-one with every employee for 30 minutes to an hour to talk about that employee’s history, hopes, and concerns. She immediately identified areas where employees were struggling.

Although it took Bryant about 90 days to meet with everyone, she considers it a great investment of time. “I can’t lead a team,” she says, “if I don’t know who the team is.”

Knowing your colleague (e.g., Do they prefer a direct approach? or Do they need to be loosened up before getting down to business?) is your responsibility and will determine the effectiveness of this conversation. When you sit down with an underperforming colleague, bring your curiosity to this conversation to understand what’s causing the problem. Questions are less likely to put the person on the defensive, and questions help you avoid making incorrect assumptions about a person and a particular behavior. Find out what’s going on beneath the surface.

To help determine your next course of action, ask the person who is underperforming to answer questions such as these:

![]() “How would you describe the situation?”

“How would you describe the situation?”

![]() “What am I—your supervisor—missing?”

“What am I—your supervisor—missing?”

![]() “Are the expectations clear?”

“Are the expectations clear?”

![]() “What does high performance look like?”

“What does high performance look like?”

![]() “If you could do it again, what would you do differently?”

“If you could do it again, what would you do differently?”

![]() “What’s your plan for getting your performance back on track?”

“What’s your plan for getting your performance back on track?”

![]() “What’s the first step you plan to take?”

“What’s the first step you plan to take?”

![]() “If you were me, what action would you take?”

“If you were me, what action would you take?”

![]() “What can I do to help you achieve the expected result?”

“What can I do to help you achieve the expected result?”

Asking the right question is essential. General questions (e.g., “How’s it going?) yield general responses (“Fine.”).

Avoid accepting the pat answer. They may be telling you what they think you want to hear.

Listen patiently without thinking about what you will say next. Drill down to locate the root of the problem. Consider not just the words you’re hearing but the tone being used to convey them. Listen for what’s not said. Watch body language.

Assess the gap between their reality and yours. Determine whether they are able and willing to improve. You cannot want success for them more than they want it for themselves.

Your assessment will help you answer the hardest question of all: How much more time will you invest in them to get their performance back on track?

CELEBRATE OR SEPARATE

High-performing companies are diligent about recruiting people who match the company’s values. Their leaders articulate clear performance expectations and then provide tools, training, and development to help the employee succeed. Leaders take a genuine interest in the person’s career, mentoring, and coaching along the way to let the employee know where he or she stands.

It’s up to the employee to take advantage of the opportunities that are presented.

Performance is a choice. If you want to be treated differently, you must start acting differently. The employee who is unable or unwilling to perform has made a choice and must be prepared to accept the consequences of that decision.

“Performance is a high expectation at Southwest,” says Elizabeth Bryant, “though we do have examples across the company where people aren’t in the right seat. So the leader needs to determine (A) Are you a right fit for Southwest, which means do you follow the values of Southwest but you’re not a fit for the job? or (B) Are you not a fit for Southwest?

“If it’s option A, we have several different opportunities within the company. We have a career transitions group that you can work with to help you assess your skills for a better job opportunity at the company. We only make that option available to people who are a good Southwest fit, just not a good job fit. If you’re not a Southwest fit, then we work on helping you find another opportunity outside Southwest.”

Herman Miller provides the tools and coaching employees need to be successful.

“If they can’t improve their performance, if moving them to a position that better suits their capabilities is not feasible … or if they choose for some reason not to address their performance, then we look at exiting them from the organization,” says Tony Cortese. “When that is the decision, we make every attempt to do that with dignity and respect.”

Each of the leaders I spoke with uses some variation of this approach to address underperformance and hold people accountable for improving:

1. Revisit expectations + consequences (the if/then contract).

2. Diagnose the problem + agree on corrective action and put the plan in writing.

3. Establish a timeframe for getting performance back on track.

4. Celebrate or separate.

With this level of clarity, the underperformer either improves, leaves on his or her own, or is terminated due an unwillingness or inability to perform. Once that happens, your colleagues often ask, “What took you so long?”

CHANGE BEHAVIOR TO CHANGE CULTURE

“In the short run,” says Nucor’s Ray Napolitan, “you might think it’s the right thing to do by being nice to people [by not confronting the issue]. But in the long run, you’re absolutely not taking care of your teammates and your obligations by letting substandard behavior continue. The key to changing any culture is changing behavior. If you don’t change behavior, you will not change your culture.”

If you can’t change the people, change the people.

When you avoid confronting underperformance, it costs you: time, money, opportunity, and reputation.