12

Finishing the Implementation: Averting Disasters

Although the most difficult tasks of the change process are behind you, there exist, as a natural consequence of success, some very powerful obstacles that you must overcome. In the last chapter we described the phenomena of inertia and momentum, and we indicated that as the change process progressed, so would the momentum progress. Moreover, we suggested the real possibility that while momentum is favorable, it can also gain too much force. Remember the pitfall of too much too soon; that is something you must guard against throughout the entire implementation of the productivity improvement.

As the product gains in popularity, there will be more and more people who are willing to experiment with it. Consequently, there will be an enormous temptation to spread yourself too thin. Over the course of the last year, you have adopted an orientation of service and cooperation, so it will be very difficult for you consciously to limit your function. However, you must do so. The problems that result from too much too soon in the apocryphal tale of Chapter 10 apply in this situation also. If you attempt to supply each individual or group with the same level of commitment you previously offered, the result will be a serious decline in quality. Since you are dealing with improvement and productivity, you cannot afford to have the quality of the effort decrease. Therefore, what you must do is continue to search selectively for small successes. Bear in mind that there is no way you can improve everyone’s work life at once; help the most capable, and then they may help some of the others. On the other hand, there are alternatives available so that you do not ignore and alienate potential users. You can always provide information: give them product literature, a copy of your user guide, and the names of the super users on other projects. This level of service may be just right for their current level of need, and it establishes a basis for future positive interaction.

The Reorganization: A Slice of Reality

We have made you aware of the dangers related to voluntarily assuming more responsibility than you are able to handle. Now we will offer advice about how to deal with a situation when you are involuntarily made responsible for more than you can manage. The most common cause that precipitates this situation is the reorganization. In order to paint a striking example of what might occur, we will share the events that occurred during the follow-up phase of the data management implementation.

When we last heard about this particular productivity improvement, the data management group had been accepted as the official source of information. During the initial stages of the follow-up phase, Sally and I performed many of the tasks described in the previous chapter: We drafted a user guide, provided consulting services and performed the ongoing activities of data administration. Our user base steadily increased, support and even enthusiasm were often expressed, and our upper management was very pleased. In fact, they were so pleased that they decided to reorganize the group. Thus three months into the follow-up phase found us reorganized into the planning division so that we could perform data management not only for our department, but for the entire section. This meant that the scope of our responsibility had tripled, and the two levels of management between myself and the director were changed. Moreover, four very inexperienced people were transferred into the group, and Sally went on maternity leave.

Initially I was gratified by this acknowledgment of our success and the increased responsibility; and I even mentally congratulated us for our tactical planning abilities. We had foreseen this reorganization during the planning phase, and had ensured that our procedures, standards, etc., accommodated the other groups in our section (see Chapter 8). Therefore we would not have to cause any disruption in the manner in which we interacted with our users. But as I was soon to discover, there were other issues to consider at this stage. For example, we now had the problem of providing service for three times as many users, while simultaneously gathering, analyzing, and loading a substantial amount of new data. Furthermore, that was only one issue. The whole change effort was in jeopardy, and I spent many sleepless nights casting about for a method to avert disaster. Actually, in retrospect, I am convinced that this is the first step in dealing with a crisis of this magnitude; you must face the fact that you are in a perilous situation. Having made that assessment, you are at least not wasting energy denying reality and are thus free to reason your way out of the problem.

While you are figuring out your course of action, you must not share your anxiety with anyone. It will not increase your new management’s or your new group’s confidence in your abilities if you are visibly upset and insecure. We are not suggesting that you lie; if your new boss inquires about potential problems with the new group structure and placement in the organization, you should definitely mention your concerns. But you must do so calmly and with the implicit assurance that you will deal with them. There are several reasons to point out the problems if asked to do so, the most obvious one being that if you gave the impression that everything was perfect and then the change effort came to a grinding halt, you would not be in an enviable position. More important, since you are going to save the situation, you do want your new manager to have registered the problems so that he will mentally give you credit for the solutions. It really comes down to the fact that unnoticed heroics will not assist the implementation of the productivity improvement or your career.

In addition to not wandering around airing your concerns when they have not been solicited, you must also not lose your nerve about commitments. It is imperative that you continue to publicly share your goals and be willing to be held accountable. You should, however, be realistic; and that means that you factor into the equation that you do now have a staff and that they are inexperienced. Moreover, we do not mean to imply that you will in all areas be doing less, because there will be some services you will be able to provide even more effectively. For example, we were getting numerous requests for reports, and within days our new staff was able to meet this need more rapidly. Thus, there are some benefits to be gained from your new staff that are realizable quite quickly.

Although the example we have described may not be exactly mirrored in your case, there may well be many similarities. Therefore, let’s list the issues that may be brought about by a reorganization:

• The very success of your effort may be the force that precipitates the reorganization.

• The result may be that your entire management chain has been changed.

• You may also suddenly discover yourself with a substantial and inexperienced staff.

• No matter how well you have planned, you will not be truly prepared for the new responsibilities.

• The first step toward resolving some of your problems is to face the severity of the situation.

• You must not share your anxiety with either your management or your new staff.

• If information is solicited, you should point out the obvious problems in this situation.

• You are not permitted to stop making commitments or to become less cooperative during adverse times.

• Immediately put your new staff to work; you will be pleasantly surprised by what they can absorb and accomplish right away.

Dealing with Your New Staff

The last item on the list is directly related to our next topic of discussion, dealing with your new staff. Even though you may be discouraged, it is important to visualize clearly that they will soon be experienced and quite competent. Moreover, in spite of the numerous demands on you at this time, you must expend substantial energy in supervising and training the group. You cannot ever afford to forget that before you even had the role of change agent, you were a manager and hence a developer of people. There may be no greater sin that a supervisor can commit than to allow people to be bored; hence your primary goal in this role is to ensure that each of your staff members has a meaningful job. A meaningful job can be characterized as one that is challenging to the individual and requires full attention all day long. The art of accomplishing this feat easily is one of the secrets of being a successful manager. In fact, if you were not motivated in this direction by an obligation to your people, there is a practical and selfish reason for doing so. Training people to be effective change agents is really your only hope for saving the situation; so somehow you must make it a priority to achieve this objective fast.

But how to achieve this objective under your present circumstances may not be at all clear. One way to begin might be by listing all the responsibilities and objectives of your group. Then try to cluster tasks that might comprise a well-rounded full-time job. This document does not have to be elaborate, nor should it require a lot of time and energy. You simply cannot waste effort on formality. A draft document with listed items is more than adequate. For example, after some reflection, it may occur to you that you need a technical support person to perform the following activities:

• Installation of PC software packages and associated hardware support

• System administration for the UNIX/3B minicomputer

• Selection of local area network hardware and software to link the mini and the PCs

• Development of conversion software to mechanically update the data dictionary used by the UNIX DBMS

• Trouble shooting and technical consultation for problems

You may also determine that you need a systems analyst to perform these activities:

• Gather the documentation from the new user groups

• Analyze the data requirements based on these documents

• Compare and analyze the new data and the data already in the dictionary to avoid creating redundant elements

• Perform logical database design and normalization

Next you want to assess each individual in terms of experience, ability, personality type, and interest; and then match each person with a particular job. This isn’t too difficult; (remember how you decided who was going to perform the evaluation in Chapter 3). But don’t assume too much; make sure you talk to each person. Finally, use common sense; give the technical support job to the woman who can install software packages on the most exotic hardware—the one who carries a screwdriver and spare memory chips around with her at all times.

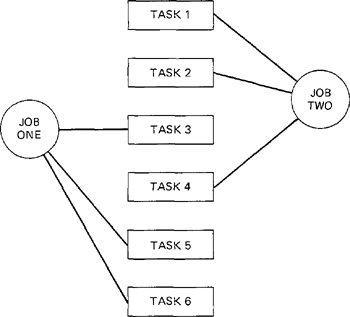

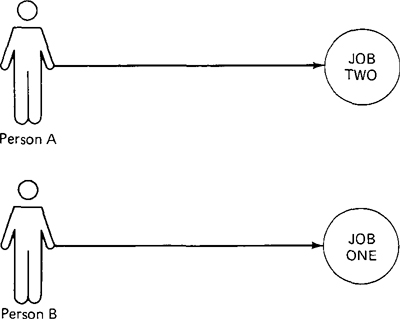

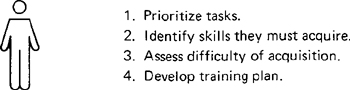

Now that you have the various jobs defined and individuals targeted for each one of them; you will need to evolve a plan to enable each of them to become fully functional. For each individual, reflect on exactly which tasks their jobs will entail and analyze the skills they will have to acquire. You also need to determine the areas in which you most urgently require help. Attempt to assess how difficult it will be for each person to learn each skill. You will have to weigh your need, the person’s experience, and balance this against the time constraints and difficulties of obtaining training. Finally, you can come up with a prioritized list that details the order in which they will be trained for each task. Figures 12–1a through 12–1d illustrate the steps in this process. For example, in the case of the technical support job outlined above, it should be reasonably easy to teach your guru the installation and upgrade procedures. This might not be the area where you most need assistance, but it will remove one burden. On the other hand, you want to avoid personally teaching skills that are complex. In the systems analyst job described above, we recommend sending the individual for formal training to learn logical database design and normalization techniques. Teaching those skills (particularly at this time) would be a serious drain on the already overworked resources of the change agent.

We have discussed in detail the assignment of responsibilities to your new staff members. We have also suggested several ways for you to actualize these assignments. So before we proceed with advice on interacting with your new management, let’s summarize:

Figure 12–1a Cluster All the Tasks of your Group into Discrete Jobs.

Figure 12–1b Assess Each Group Member.

Figure 12–1c Target Each Group Member for a Specific Job.

Figure 12–1d Enable Each Group Member to Perform Job Fully.

• In your enthusiasm as a change agent, never forget your role as a supervisor.

• This role includes the development of your people, especially as it relates to defining a meaningful job for each of them.

• Job descriptions can be developed by listing and then clustering all the responsibilities and objectives of your group.

• Taking into account each individual’s experience and interest, assign each person to a job.

• Develop a plan to enable each group member to become fully functional.

• Factor into the equation your own needs and resources at the time.

• Do not expend precious time and energy preparing formal documents, because lists of items are more than adequate.

Dealing with Your New Management

Now we need to concentrate on dealing with your new management. Because you are so far along in the change process, abandonment of the productivity improvement is not a serious threat. However, during the follow-up phase of the data management implementation we did find that with each new manager, there was a shift in priorities. Shifting priorities can present significant problems.

At one point the data management group was working for a visionary manager, and therefore we were in the midst of redoing the data architecture for our section (this scenario will be discussed in detail in Chapter 14). Following a surprise reorganization, we found ourselves working for a very practical management team. They were not at all interested in a course of action that would require several years and consist of a gradual migration to subject databases. Their highest priority was to have each programmer change the name of every data element to a common name in every program so that we would have consistency. In fact, my manager’s manager stated unequivocally that he would not believe he had gained anything through data management until it was reflected in the code!

This scenario may sound vaguely familiar. During our implementation of Excelerator, we described a similar suggestion which was proposed by a planner on the project team. We discussed our rejection of this idea and our reasons (see Chapter 9). In the data management case, we had bypassed this option during the previous regime because it just did not seem worth the effort. If we were to modify all the code in all our systems’ software, then we believed fervently that the result must be a state-of-the-art architecture, which surely would include subject databases. Although at this stage we had not progressed much further than assessing the need, we were wholly committed to this course of action.

What must (and did) happen in these cases is that you resume the role of salesperson and you sell the new management, just as you sold the original management. The sales pitch, however, is different for several reasons. You should by this stage of the implementation have numerous, substantial, and tangible benefits to display, so there should be immediate acceptance of the credibility of your effort. Conversely, you do not as yet have influence and personal power with your new boss. In the original situation, you had to sell the product; in the present situation, you have to sell yourself. (Actually, to ensure your political safety, you need to do this whether or not you are an agent of change.)

There is no script for this one, because you will be endeavoring to steadily improve the dynamic interaction between yourself and another person (your new boss). The interaction will, of course, vary from individual to individual, but there are some techniques (such as empathy) which you have utilized throughout the change process that should be extremely helpful. For example, you will be tempted to immediately enlighten your new boss about your mission, its history, and its purpose; however, he may be suffering from an overdose of information. Don’t add to his load by detailing the entire implementation in one session; practice effective listening. Then you can take your cue from him, be flexible, and apply the technique of meeting him on his own ground. If he is indeed a detail person, give him copies of all your documents. He can read them at his leisure and call you when he has questions. If he is suffering from overload, treat him the same way you treat your very busy upper management. But don’t assume, pay attention, get the lay of the land, and employ the skills you have developed along the way. All this will quickly build up a level of trust and confidence that will result in your possessing enough influence to reshift the priorities.

Let’s pause and recap what the reorganization may mean to you in terms of your management:

• Changes in your management will surely result in a shift of priorities.

• This shift may result in a direction that is both dramatically different and unacceptable to the fundamental philosophy of your effort.

• You must resume the role of salesperson to achieve a resumption of the original priorities.

• This time the purpose of your sales pitch is to sell yourself, not the product.

• You will utilize skills that you have developed throughout the change process to create the proper environment between yourself and your new boss.

Modularity and Continuity of Approach

Even after I began to train my new staff and unload some of the work into their increasingly competent hands and I had begun to win the trust and confidence of my new boss, I remained in a serious situation. It was certainly to my credit that I had hastily developed a plan and once again laid the groundwork for the proper environment, but there were still some difficulties that related to the doing. My problem was directly related to the integrity of the new data dictionary. The one aspect of this change that made it so attractive was that finally there was a userfriendly and reliable source of information. My quandary involved the thought of sacrificing this security and integrity by allowing an inexperienced staff to update the dictionary. Of course, if I did not allow them to update the dictionary, not only would new projects not get included, but they would not be able to learn their jobs.

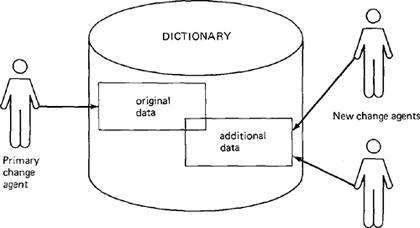

My solution to this paradox was modularity. I partitioned the data so that what had already been loaded was in one portion of the dictionary. I then established a new partition for the data associated with the new departments we were now also responsible for. There was a natural division of the data, since one set of systems was for operations support and another was for management information. Since there was some overlap of data elements, I created a concept of ownership; only one partition owned each data element, and that was the only place it could be updated. Then I personally managed the original data that already had a high degree of integrity and was in use. I put my new staff to work on the other partition so the new data could be loaded, analyzed, and verified. This meant that I worked weekends for about a month, but I was determined that there would always be at least a portion of the data that would be valid and thus truly useful (see Figure 12–2).

This concept of modularity can be extended to any productivity tool or technique. The basic idea is similar to manageable chunks; i.e. you can modularize the change that has already taken place by dividing it back into the chunks that were managed or already implemented. Once you mentally reverse the process, you can ensure that the productivity improvement that has already been accomplished remains useful. Remember the concept of intermediate goals; this modularity is a continuation of that objective. The goal becomes not only to deliver, but always to maintain something that is beneficial to the user.

The other technique that can be very important, especially during periods of adversity is what we call “continuity of approach.” This is really nothing more than continuing your commitment to a service orientation. Even though you are pressed by many problems, your attitude must not become less cooperative and helpful. Furthermore, you will have to instill this attitude in your new staff. If they do not always have solutions for the users, at least they will be friendly, helpful, and make every attempt to supply all the needed information. Since your staff is steadily increasing their knowledge base, they will soon be able to solve more and more problems. Then, because they have both the knowledge and the proper attitude, the user community will want to interact with your group as well as with you.

The techniques we have just described are very important. You might want to review their salient features, as stated below:

• Modularity provides a way to maintain what is already useful and beneficial to your users.

• Continuity of approach applies not only to yourself, but extends to your new staff.

Figure 12–2 Modularity was Concretely Employed by Partitioning the Data Dictionary.

• Both techniques enable you to offer products and services that are worthwhile even under adverse circumstances.

Reevaluate the Plan

Following a reorganization, you may have to face an adversity that is related to peripheral people resources in your previous and current organizations. In our case study, we experienced direct impact to one of our work items when we were moved to the planning division. We had on our schedule activities to implement a local area network so that our users could have on-line access to the data dictionary. When we developed that schedule, we were part of the technical support district and thus had considerable expertise available to complete the activities. After we were reorganized, there was no one in our new division with the technical background required to implement the local area network. Considering that we had survived for a year without the LAN, and considering all the other situations I had to address at that time, I relegated this one to the bottom of my list.

The story about our LAN work item should convey that whenever there is a major organizational change, it behooves the people who are implementing productivity improvements to reevaluate all scheduled activities. Actually not blindly adhering to the schedule but rather constantly reassessing the situation is a skill acquired in the doing phase. Thus the message you should absorb at this point is that you need to continue exercising that technique for the rest of the change effort. At any stage it may well be the case that some voluntary shifting of priorities will not only alleviate some stress, but may actually improve the rate of implementation. In our case we had originally planned to load all the data into dictionary in the following order:

• Interfaces

• Databases

• Screens

• Reports

We had scheduled the databases second because as part of technical support, we were organizationally and geographically close to the programmers. After the reorganization we were organizationally and geographically close to our end users, and thus it made sense to load the user view into the dictionary next. Our amended schedule was as follows:

• Interfaces

• Screens

• Reports

• Databases

Since the screens and reports were much better documented (via user guides), the percentage of data loaded was increased more rapidly.

In Chapter 6, we introduced our experience with data management, and at that time addressed the same issues when we described brainstorming activities. The summary there contained three items that apply at this time also:

• Select an alternative with a very high probability of success.

• Consider very carefully your resources and the potential effect they could have (or their lack could have) on any given approach.

• Make sure you use your resource analysis to increase the chances of success.

Notice how the themes of the earlier phases are reiterated again and again, particularly when you are finishing the implementation. This is no accident; the issues do not change, but you are still dealing with people and all the unpredictability this represents. Thus you will continually encounter unplanned obstacles, which you can now begin to view as challenges. After all, at this juncture you certainly possess considerable expertise in all the skills required to be a successful change agent.

Attempted Political Takeovers

Although the reorganization is the most severe hazard that can occur, it is by no means the only one. Another major area of conflict is also related to the success of the implementation thus far. Up till now, except for some minor skirmishes during the interproject team days, no one has considered you a competitive threat. However, now that the productivity improvement has become popular and is enjoying a fair amount of attention, you must prepare to defend your stronghold. In our case, what happened at this stage was that a significant number of people suddenly became data analysts and many projects were unexpectedly (and amateurishly) normalizing their data.

There are a number of ways to combat this situation; and for some of them you have already laid the groundwork—the “roles and responsibilities” document you and the interproject team developed. The significance of this document at this particular juncture is that it clearly defines your turf. Moreover, the fact that it was prepared by the team strengthens your position; it is likely that individuals from the same group as your opponents helped develop the document and thus shape your collective destiny. That it did not come solely from your group but was a product of the organization goes a long way toward discrediting your opponents. Their claim for the reasonableness of their performing your group’s job functions was surrendered long ago in the planning stage. If they persist, it is even possible that they will antagonize some of their co-workers who were and are part of the change process.

The only action you must take is to ensure that the document is recirculated at this time. You also want to make sure that your management is aware of its existence, its history, and its current relevance, because they may have some political issues to resolve with their peers. In fact, this may be an optimal time for you to begin providing your boss with some additional details about the implementation. You both have had some time to adjust, and by now the foundation of the relationship has been paved with mutual trust and confidence.

Last, try to devise ways for you and your group to be highly visible when these political issues arise. Heightened visibility will reaffirm your position as well as further establish the position of all levels of your new management. As we mentioned previously, during times of stress it is not likely that the implementation will come to a halt, but conflict drains the resources of everyone associated with the change. It is your objective to reduce the stress, so anything you can do to present the change effort in a positive light will help. You might, for example, arrange a presentation of the current status of available information and its usefulness.

Taking a Stronger Stand

As you gain political strength, there may be a tendency on your part or some pressure on you by your management to take a slightly stronger stand. This small adjustment of orientation may be very appropriate; it could well be the exact moment to lean a little on the project that was always so evasive. Possibly the manager has a history of expressing interest, but you can never get a commitment for an hour of her time. Send her a memo which states the same objectives you would have for any strategy meeting—information exchange and mutual direction setting (see Chapter 11 for details on the strategy meeting). In addition, provide at least five specific days and times that you are available within the next two weeks. Carbon copy your boss for the twin purposes of enabling him to pursue this if he so desires, and allowing the other manager to know your offer is public knowledge. All this will make it very difficult for her to continue ignoring you.

You may recall that in Chapter 8, we described a type of power struggle that is of a passive nature. The difficult individual exhibits extreme nonconformity, such as agreeing with all team members but then pursuing a direction in opposition to the team’s efforts. We pointed out that this behavior is not only very resistant to positive overtures from the team leader, but severely demoralizes the team. Our experience indicates that the situation is not hopeful, and we advised removing this individual from the team if at all possible. If this was not an option, we promised final resolution of this problem in this chapter. Well, the moment has arrived: If she is still in your organization and still persisting in her maddening ways, your opportunity to address the situation is at hand. Very simply, you now have so much power that even the most stubborn of souls will no longer be able or willing to fight you.

We had a firsthand experience with a case such as this one when we implemented Excelerator. One project team member followed this pattern in every one of its annoying details. Since there was no possibility of her removal from the team, we existed with some considerable frustration. While the team was establishing standards and naming conventions, she was assigned (as project leader) to what was deemed to be the most important development project in our organization. She did not follow even one of the rules we had evolved, and thus the name of every single entity (elements, records, processes, etc.) in her system was different from those in any other system. This disparity did not lend itself to identifying redundancy and possible common routines. We handled the situation by manually renaming every entity when her system went into production. Due to the fact that I was not able to impress her with the seriousness of the inconvenience to my group, I approached her boss. I explained the situation to her manager and said we would never convert everything manually again. By that time I had attained enough power (both positional and personal) to enforce this claim. Our rugged individualist was in the end forced to a humdrum life of conformity.

As you can see, many different perilous situations may arise while you are finishing your implementation; we have mentioned only a few possibilities. However, the suggestions we offered should be generally applicable to help you resolve most of the crises. Here is a summary of the issues we have discussed:

• The reorganization is not the only adversity you will encounter once your change effort is widely perceived as successful.

• You may now be viewed as a competitive threat, and hence must be prepared to defend your turf.

• This will be made easier for you because of the “roles and responsibilities” document the project team developed during the planning phase.

• You now have enough political strength to exert pressure in some areas where you have been tolerating considerable frustration.

One final thought about your political interactions; do not lose sight of your goal to create the proper environment in which change can take place. It may be appropriate to utilize some of the political strength you now clearly possess, but do so judiciously and gently. We have stressed the importance of instilling in your users both trust and confidence in you, your group, and the change effort itself. Maintaining the proper environment is also critical for continued success. You really do not want to undo your effort with a senseless display of power. Moreover, you must also feel confidence and trust in your users; confidence in their willingness and ability to participate in the change process, and trust that they will be sincere and fair. We have found that it is better to start from a position of confidence and trust until it is clear that this is misplaced. If you do so, more times than not, it will be justified. If you do not do so, then it will not be possible to expect others to have confidence and trust in you, and there is no hope for ever achieving that proper environment.

Summary

• Your success in implementing the productivity improvement will precipitate some very powerful obstacles that you must overcome.

• You must guard against voluntarily assuming more than you can handle, as well as dealing with involuntarily being made responsible for too much via a reorganization.

• Following a reorganization, you will have to re-create the proper environment; this includes selling your new management, and supervising and training your new group.

• Properly supervising and training your group is a basic component of your job as a manager. Moreover, it is your only hope for salvation, so make it a priority.

• To maintain the level of success you have already achieved, you will use the techniques of modularity and continuity of approach.

• You will now have substantial political power and it will be appropriate to utilize some of it, but do so judiciously and gently.