6

Gathering Information

During the last phase, you were engaged in providing information. The phase of gathering information is a quiet or more thoughtful part of the change process. Your goals during this period are to obtain information from your users, to generally size up the situation, and to set your course of direction.

Let’s examine these objectives in more detail. First of all, you must take the time and effort to understand your users’ point of view. I know that this statement may seem somewhat redundant. After all, it does seem that all we did during the previous phases was to view reality from their perspective, and this empathy assisted us in literally every step of the way. However, in actuality, we were projecting our own experiences onto our perception of their viewpoint.

Effective Listening

Remember the project control and tracking tool we mentioned in Chapter 2? At that point we discussed utilizing the art of empathy to determine what will truly benefit your users. We proposed some guidelines for gauging accurately which tools will truly improve their work life. But no matter how much empathizing you do, or how skilled you are at this art, you are still only guessing. To be sure, since you are a project manager yourself, you will be accurate. But you still need to ask other project managers for their opinions. Therefore, what makes this phase different is that you are now going to ask your users directly for their views and listen intently to what they have to say. Moreover, you must never underestimate either the importance or the difficulty of effective listening. Most people would quickly agree that listening is important; however, very few realize exactly how complex an aspect of communication it is.

Listening has been described as a skill that is underdeveloped in most people. We learn to talk and indeed are taught that communication skill, but no one ever teaches us to listen. If you doubt that there is a lack of significance placed on listening, consider the number of books you have seen on the subject versus those written on effective speaking. The bottom line is that currently most of the emphasis in communication is on talking, and there is an almost appalling lack of attention to the skill of listening. Moreover, in the overwhelming majority of books on speaking, there is usually a section on how hard it is to get anyone to listen!

I have taken courses that claim listening is the most important aspect of communication. Too often, when others are speaking we are framing our next sentences or daydreaming about something totally different from the subject at hand. One of the theories I have heard is that the mind processes faster than anyone could ever speak, and therefore your mind leaps ahead. So we need to exercise discipline and improve our ability to listen effectively. To facilitate your development, you should begin by avoiding inadequate listening, as the following example illustrates.

Suppose you are proceeding with the implementation of the project control and tracking tool that has already been mentioned several times. The potential user that you have approached to discuss the tool has launched into a detailed description of the problems the project team is having with each enhancement that is included in the current release of her system. You find yourself mentally drifting away from the conversation and focusing on last night’s TV show. Then it occurs to you that you have mapped out a mental schedule for the day that includes talking to six other potential users, and you begin to become very impatient. Furthermore, you used to be the project manager for this particular system, and so you are well aware of all the release problems.

There are several specific ways that you can improve your listening effectiveness in this particular scenario. The first matter for attention is that when the project manager is listing the enhancements and associated problems, you may conclude that she is not addressing your concerns. That conclusion may well be a mistaken assumption. For example, if you listen very carefully to each enhancement and each associated problem, you may see very clearly a possibility for incorporating the tool that will be reasonably easy and will demonstrate immediate and direct benefits. You want to file that information away for use during the implementation. The next item to consider in the scenario is that you must be patient. You cannot hasten this process, and it is much more important to listen to only four users and truly hear what they have to say than it is to reach some quota.

The fact that you had managed the project yourself and therefore could smugly assume that you understood the entire situation illustrates another common pitfall to avoid. You really cannot assume that you know what is being said after a few key phrases and proceed to mentally frame your response. You should also not rely on previous experience to predict what will be discussed. For example, the way the project team develops systems may have changed since you were in charge.

Based on the discussion thus far, it would seem that listening is a passive skill. But that is not totally true. You must also listen to what is not being said, and ask questions to draw out the person. This is also critical to the art of being a good systems analyst. Remember how you ensured that you had all the user requirements for the next release? You listened, you persisted, and you asked questions. Asking questions, even vague and half-formed ones, will probably get your user started.

This brings us to the another critical aspect of interactive listening—you must direct the conversation. In order to hear what is important, you must get the user to focus on the real issues. Allow a certain amount of digression. After all, as we pointed out above, she may touch on issues that not only had you not thought of, but that will be valuable later in the change process. However, you must keep bringing her back to what is important until you reach some point of resolution. This requires considerable patience and tenacity, but the technique will become easier the more you use it.

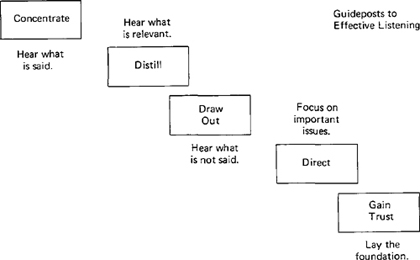

In addition to enabling you to obtain information, there is another important benefit of effective listening. Feeling secure that another person is interested in what we have to say and that we will be heard makes us feel good about ourselves. Furthermore, it motivates us to increase our interactions with that person. If people want to interact with you and your group, that will certainly facilitate the implementation. If you allow your users to express themselves and truly listen to what they are saying, you will provide them with substantial confidence in your sincerity as well as the entire effort in general. Therefore, not only is listening a key to success during this phase, but it will also help lay the foundation for creating the proper environment in which change can take place (see Figure 6–1).

Figure 6–1 Effective Listening.

Before we end our discussion about effective listening, let’s summarize some of the points we have covered:

1. Listening is a very important part of communicating.

2. Listening is a skill (usually underdeveloped).

3. Applying self-discipline allows you to utilize this skill.

4. Listening is an active as well as a passive skill.

5. The active aspects include stimulating conversation and directing it.

6. Effective listening promotes the proper environment for change.

Sustain What is Already Productive

Now that we understand the importance and techniques of communicating via listening, let’s focus on the concrete types of information you will be seeking. The main thought to keep in mind is that your users are already performing the function you are trying to mechanize and improve. Therefore, they will provide you with valuable information about the following:

1. The aspects of the current method of performing the function that they find extremely useful in achieving their daily objectives

2. The aspects of the current method or operation that they find user friendly, pleasant, and interesting

3. Tasks that they find difficult, repetitive, and time-consuming

4. The fears and concerns they have about the changes you and your group are trying to effect

The first two items are sometimes overlooked—or even worse, the agents of change assume that they know the answers. You want to make sure that you do not omit anything from the current procedures that is inherently productive or especially appreciated by the users. In Chapter 3, we presented an example of introducing a new release planning and scheduling tool. At that time, we focused on ensuring that the tool was compatible with the modality of your organization. That was another way of addressing the same issue: When you select/evaluate a product as well as when you prepare for implementation, you want to retain anything that is positive about the current environment. Therefore, you should make a sincere effort to understand any productive methods and procedures (formal and informal) that are already in place before you plan the future environment.

The third item, which focuses on the unpleasant and thus potentially unproductive aspect of their jobs, should be used to confirm or dispute your original assumptions. Don’t worry; it is highly unlikely that you will be way off the mark. You may, however, have to modify slightly which subfunctions you were planning to improve first. The following scenario illustrates this type of modification. Suppose the target area you had selected was definition and design, and you had chosen an analyst support tool to utilize for productivity gains. Your original set of assumptions centered on the functional/processing aspects of development during these early phases. However, after you begin talking to your users, you discover that they are quite satisfied with the current method of defining and designing the functional side of their systems. You also discover that with almost every release there is a major communication mishap that results in incorrect record layouts. What you must do in this case is reconsider which subfunction of the definition and design phases you will begin with. You may then decide to begin the change process (using the same tool) with the data side of development.

Eliminating Fear

The last item on the list is very important for several reasons. The most obvious is that it refers to the whole issue of resistance. One of the most important and fundamental ways you can promote acceptance is to make people feel comfortable about the change and the new way of doing things. In order for you to be able to create this positive environment, you must understand as precisely as possible exactly what it is they fear. This is true because fear really is one of the major causes of resistance. For example, suppose you are introducing a tool to the system test group. Currently, test cases are entered manually by each person in the group. Moreover, each test case is invented by each individual. There is no detailed test script, and group members work from guidelines or a general set of rules. The new tool, which is menu driven, prompts the user with a series of questions, generates the test cases, saves them in files, and then executes them on command. You have projected that considerable savings will be realized with this tool not only because the test cases will be generated, but because they will be reused by many individuals for many releases.

However, when you talk to the people in the test group, you discover that many of them do not view this change as positive and some people are even hostile. After listening (effectively) to what they are saying, you find out they are afraid that many of them will be removed from their present positions. Notice that we did not say they were afraid of losing their jobs. Although you will find a few people who are afraid of this, we do not believe this is a common cause of anxiety among data processing professionals. People are more concerned with losing whatever it is that they value about their current position—the possibility of promotion, no longer working with the peers they like so much, or simply the work itself, which they find enjoyable. If they get transferred or if the group is dissolved, any or all of those concerns could become realities.

You need to be cognizant of and sensitive to these fears throughout the entire process of implementing change. If this is very unlikely to occur, make that unequivocally clear. In the case of the system test tool, there may have been such a backlog that there will not be a reduction of personnel, but rather more (and higher-quality) releases of the system every year. If it is inevitable that the size of the group will be diminished, do not try to deceive the group members. Although you probably would not want to point this out, it would be a serious mistake to lie if you are asked directly. Remember you still have a long road ahead of you on this particular path and you never want to risk losing credibility. Try to be positive and point out other opportunities that are available both within and outside your organization. Unless your data processing environment is most unusual, there is bound to be plenty of work for competent people. There may be someone you would like to encourage to join your own group when the time is appropriate.

You may find that the only major source of resistance will be the group manager, who is not at all pleased at the thought of managing a much smaller group. This can be a very tough situation, but one option that might be available is to make this person an active part of the change process. For example, make his group the pilot for the implementation, include him in the earliest steps of the planning process, and widely publicize his involvement. You can afford to share the glory; there will be more than enough to go around.

The Interview

When they are involved in the activities outlined thus far in this chapter, some people will develop questionnaires and have a formal interview process. Personally I prefer a more informal approach, such as dropping by my users’ office (when they are not busy) and engaging them in casual conversation. I believe you will get more information in this type of setting. However, if you feel more comfortable with the questionnaire, either form of interview can produce good results. Whichever approach you choose, consider the following set of sample questions that might serve as a starting point for our project control and tracking tool:

1. For each release of your system, do you currently decompose the phases into activities, and the activities into tasks?

2. If so, do you assign specific people and due dates to each item?

3. Do you compare this to available resources such as machine time?

4. Do you compare this to unavailability of resources such as how much time these people will devote to maintaining the current system?

5. How easy is it to gather, analyze, and maintain this information accurately?

6. Do you then track the rate of progress by running regular reports on a daily, weekly, and monthly basis?

7. How easy is it to run these reports?

8. How useful and accurate are these reports?

9. Who utilizes this information? only yourself? your group? your boss? your upper management? your users?

10. Do you believe this helps you get your system delivered in a more timely manner?

11. Do you believe this improves the quality of your system?

12. What do you find particularly time-consuming and difficult about the process of project control and tracking?

13. What do you find particularly boring and repetitious about the process?

14. What aspects of the current process could you not live without, no matter how marvelous a tool you had?

15. Is there anything about the new tool or your understanding of our plans that concerns you?

For our project control and tracking tool, these questions would be adequate coverage of the four areas we mentioned earlier in the chapter. Of course, in a real situation you would have many more questions, and they would vary from tool to tool as well as from user to user. If at all possible, try to adjust the order as well as actual questions to each individual you interview. As you gain more experience you will be capable of increasing flexibility, which will result in your obtaining more information.

Identifying Key People

While you are spending this time talking or rather listening to your users, there is another type of information to be assimilated that will be very useful to you during the next several phases. During this period you will have the opportunity to examine the dynamics of each major subset of the organization—to determine where you can anticipate support and where you can expect to meet the greatest resistance. This is the type of information gathering that we had in mind when we proposed one of the objectives for this phase as generally sizing up the situation. Not only will you need to know who will be a supporter and who will be a resister, but you also should determine who is the key person in each group. There is a theory of management, Situational Leadership, that addresses this topic. Every group has a manager, and as you would suspect that is the person with the position power. Every group also has its self-appointed leader who is the individual with the personal power. Of course, it is sometimes the case that the manager has both the position and the personal power, but not as frequently as you might expect.

What is important to you at this time is to determine for as many groups as possible exactly who has the personal power. Then you will mentally select a few of these individuals who appear to be open-minded about what you are trying to achieve. These will be the people you will want to work with during the planning and implementing phases. Moreover, you will mentally note individuals with personal power who appear resistant or even uninterested. Since you want successes early in the change process (more about this later in the chapter), you will want to delay heavy interaction with these people. But be open-minded—it has certainly been our experience that sometimes those who appeared difficult initially became our staunches! allies in effecting change.

Brainstorming

During the time you and your group are interviewing users, you also need to be brainstorming. It is my experience that this is the best and fastest way to reach your third major objective for this phase, setting your course of direction. Moreover, it is important to understand that at this point you are not charged with developing a detailed action plan, but rather a general game plan.

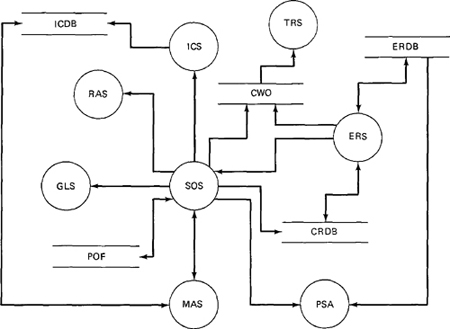

Several years ago, the particular vehicle we chose for improving productivity was instituting mechanized and centrally coordinated data management in our organization. Of course, we had already assessed the need, selected and evaluated the product, and sold our management and users. We were in the midst of listening to the user perspective on the benefits and limitations of our current methods of data administration. Our problem was not that no one was performing data management, but that each group was doing it differently for each phase of the development life cycle. We had data elements that were shared by every system, such as customer id, that had 35 aliases during the logical phases of development (definition, design, etc.) and literally hundreds of aliases in the actual code. This situation was further complicated by the fact that we were dealing with a family of interfacing systems (see Figure 6–2). The obvious result of such an uncontrolled situation was that there were delays in the releases and plenty of dissatisfied users.

Figure 6–2 Family of Interfacing Systems.

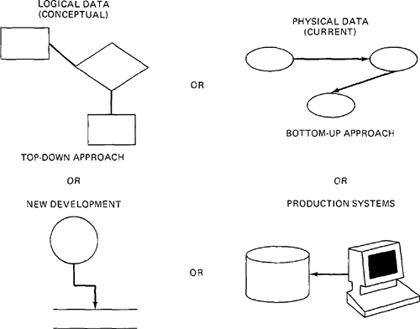

Two of us were given the opportunity to improve this situation and were finding it fairly easy to interview our users (most of whom we had worked with for years). On the other hand, we were having considerable difficulty figuring out how to begin our implementation. We had discussed the possibility of a top-down approach beginning with a conceptual or ideal view of the data based on our end users’ needs. We had also discussed the bottom-up approach beginning with a catalog of the data as it currently existed in our systems. We considered whether it was better to start with production data or have a pilot working in conjunction with a hot new development project. We thought about the pros and cons of beginning with one system we both knew very well versus the pros and cons of beginning with the common or shared data. We created matrices charting user communities and types of data. We filled up white boards in both our offices. We debated and argued every conceivable possibility from every conceivable point of view (see Figure 6–3).

Finally, after about two weeks of this agony, she walked into my office, looked up at the white board on which we had categorized all the information in all of our systems, and had a flash of insight. We began to view everything from a different vantage point and promptly outlined a skeleton. We refined the game plan and went forward to the next phase.

Figure 6–3 Brainstorming the Dilemma of Determining Where and how to Begin.

What we decided to do was begin with the interfaces between our systems because they were the most critical, due to the fact they affected two major applications. Moreover, due to their importance, they were the most stable and best documented. Therefore, we began with something very important, and we had a good chance of success. (The idea of moving the implementation in a direction that will result in a series of successes is an important concept that we discuss in detail in the next few chapters.) We also decided to adopt the bottom-up approach. We thought it was important to have an accurate picture of the present reality before designing an ideal view of the world. In that decision we were also largely influenced by the fact that we were part of technical support. Due to our organizational placement we were removed from the end users, which would have made it very difficult to have all the effective interaction necessary to develop a reasonable top-down model. As a matter of fact, we were also removed geographically from the end users, which would have made it even more difficult to produce the ideal model. On the other hand, we were organizationally and geographically close to our programmers, which would be a tremendous asset for the bottom-up modeling effort.

We were quite successful in instituting mechanized and centrally coordinated data management, and whenever we get together we reminisce about the brainstorming. We differ, however, on our predictions for an alternate reality. Looking back across the events that followed, I am convinced that many of the approaches would have worked because the time was right, the tools and techniques we had chosen were good, and we were committed personally and supported by our management. My friend, however, believes that any other approach would have been a false start, and we would have wound up with the approach we took in any case.

The main points to bear in mind about this story can be summarized as follows:

1. This is a difficult, challenging, and exciting step in the process.

2. Because of item 1, it is possible to spend a lot of time on this step. Don’t do it; limit the time as you did with other steps.

3. The result was not at all detailed; it probably would not have filled one typed page.

4. Several alternatives will be developed, and more than one of them may work very well.

5. Select an alternative that will be important to management and users alike.

6. Select an alternative with a high probability of success.

7. Consider very carefully your resources and the potential effect they could have (or their lack could have) on any given approach.

8. Make sure you utilize your resource analysis to increase the chances of success.

9. Do not worry about the prospect of selecting an untenable alternative, because it is just a basis for the detailed planning phase and thus can be modified without jeopardizing the implementation.

Importance of this Phase

One of the points you could not have gotten from the story is that this truly is an essential step. If you omit it, you will start the next phase at a serious disadvantage. Exactly why this is so will be explained in the next chapter. But before we move on to planning the implementation, there is a strong advisory that must be shared: There is a high probability that your management will exert pressure on you to shorten or even bypass this phase and the next one. After all, they have been sold, they provided resources (people and time), spent money, and gave their blessing. Now they want concrete results and they want them fast (possibly to keep their management satisfied). Don’t even consider this as an option. Reflect on all the valuable information you have as a result of the activities you performed during this phase. Project forward and imagine how much value you will gain from the planning phase. These phases are as essential and critical as any other.

You must explain the necessity of spending this time on pre-implementation activities to your management. If they are unwilling to listen to your explanations of why this is necessary, then you must fight. They would not expect you to begin developing a system by coding it; and they know from experience that when you do circumvent the up-front steps in the development process, it takes more time in the long run. Point out to them that this is similar to taking time to design a system.

They will surely understand this analogy. Promise to recoup the time during the actual implementation, and then do so, even if it means that you work every single weekend and evening. Emphasize that you are in actuality only asking for one more month for this phase and no more than two months for the next one. It is not as though you were adding a year or even six months to the schedule. Above all, have faith and do not back down; they will give you the time. Do not forget that what you are attempting to do (to improve the data processing environment for the whole organization) is important. You were correct in your original assessments, you are an accomplished salesperson, and your management has tremendous confidence in you, or you would not have gotten this far.

Summary

• Your goals during this phase are to obtain information from your users, generally size up the situation, and set your course of direction.

• Information can best be obtained by employing effective listening, which is a very complex and underdeveloped communication skill.

• The types of information you must gather from direct user input include aspects of the current mode of operation that are inherently productive, as well as their concerns about change.

• You must also determine who will be the key players—who is likely to be a supporter or a resister as well as who has the personal power.

• The third activity of this phase is to develop a basic game plan, and the best route to that end is via brainstorming.

• This phase and the planning phase are as essential and critical to the change process as the design phase is to software development.