2

Selecting the Candidate Products

The guiding star for you during this phase must be to set reasonable limits in terms of time and scope. We have all known people who have undertaken the responsibility for productivity tool selection and then disappeared for the next decade. Since no one deliberately sets out to make a career of tool selection, we must begin by identifying why this is a trap into which so many people stumble. The trap is very simply due to a phenomenon that we call “chasing the rainbow”; i.e., there is so much software and hardware currently available or under development that it is literally possible to search forever for the perfect tool.

The fact that there are so many choices is further complicated by one of the very personality traits that attracts us to data processing—our interest in and enjoyment of new technology. This predisposition on our parts enables us to experience an almost childlike joy in this phase. What lies immediately ahead are the tasks of discovering and exploring new tools or techniques, and then determining their applicability to your environment. You will also have the opportunity to meet and interact with many new people. All these activities and interactions will be quite intellectually stimulating. Moreover, since it may often seem that we are bombarding you with concerns, cautions, and hazards to avoid, it is reassuring to realize that there will actually be activities that will be enjoyable.

However it must be clear that not only are the possibilities virtually limitless, but also the process of selecting can be itself seductively fun. Therefore the critical success factor for this phase becomes the fundamental issue of setting your own limits. First of all, you must consciously separate selecting candidate products from the process of in-depth evaluation. The selection phase should include a market survey of what is currently available and culminate in selecting a few (no more than three or four) products that will be thoroughly evaluated in the next phase. This distinction is essential, because if you begin the selection process with an exhaustive critique of products, you will inevitably succumb to the “chasing the rainbow” syndrome.

To assist in the process of setting limits, we offer the following four axioms, which have proved invaluable to us:

1. To avoid premature and nonproductive attention to detail, keep your objective firmly in mind at all times; i.e., to perform a market survey of possible products.

2. Set a specific date by which time you will have made your selection.

3. Have a specific (not necessarily complex or detailed) procedure firmly in mind before you begin.

4. Have a very clear definition of what would be required in order for this tool to be effective.

Setting the Due Date

It may seem that setting your due date will be affected by many factors, such as the complexity and magnitude of the change, and whether or not you are still acting under your own initiative. However, we have implemented change in a wide variety of areas—from a new editor to automated software for the whole development process—and firmly believe that selection time cannot exceed two months. This may seem minimal to you, but don’t forget this is a survey only, and does not include an in-depth evaluation of even one product.

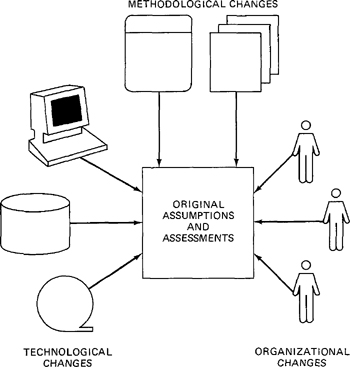

Although it may seem that this time frame is arbitrarily brief, it is essential that you consider how quickly everything changes in data processing (people, technology, methods). Therefore, if the combined time for selection and evaluation exceeds three to four months, there is a high probability that your original assumptions and assessment will no longer be valid (see Figure 2–1).

Let me share with you an experience where we were thwarted in our attempt to implement change by a lack of timeliness. At that time, which was quite a few years ago, I worked for a dynamic boss who was not only enthusiastic but also technically astute. He was the type of individual with a steady stream of new ideas about a myriad of ways to apply the latest breakthroughs in our field to applications development. This was the data processing era, when microcomputers were just becoming viable in commercial data processing, and my boss began a self-initiated study of their applicability to our environment.

I was chosen as his fellow agent of change, and together we assessed our organization’s needs, as well as the timing for this type of change. He shared and sold our concept to upper management, who supported our efforts. In fact, our study was well publicized internally and externally. In certain areas, the results were eagerly awaited. We proceeded through all the steps that will be outlined in this chapter and made considerable progress quite rapidly. It is not at all difficult for me to remember the satisfaction and even pleasure I received from performing the tasks assigned by my boss. He not only exposed me to many new trade journals and magazines, but also to whole new areas of the computer field. He enabled me to gain confidence in my planning, technical, and interpersonal skills. We visited many different vendor sites as well as those of other customers. All in all, we had fun!

Figure 2–1 External Change Can Adversely Affect a Change Effort.

At last, we were putting together the final report, which included a detailed recommendation for strategic implementation of micros in key development projects. At that point we experienced difficulty with our new word processor creating some tables that were an attachment for our report. These difficulties delayed distribution by several weeks. During these two weeks, our department underwent a major reorganization and our group was moved to another department with different upper management. The new management considered microcomputers toys that had no place in our environment. We were not permitted to distribute even a draft version of our report!

I still have a copy of this study and I still believe that much of it was insightful and that the information would have been useful to many people. Moreover, if we had issued the report without the tables, it would have been just as valuable to every one of our potential readers. However, we lost sight of our major objective, unnecessarily delayed our due date, and thus were undone by time and politics. We are not advocating a sloppy job at any step of the way; but it’s a fact that even if something is of the highest quality, it is useless if time and opportunity have passed. Of course, you are the one who chose the target area, and now you must be the one who will ultimately decide how much time to allow. The main point is to establish a cutoff time and then not to revise it.

Having examined the adverse effect of inadvertently changing the due date, let’s examine a few of the factors that may seem to affect not only time allotted, but also approach taken for selection. The area you have targeted for change would seem to dictate the time and manner of your search. For example, looking for a new word processor is a whole different order of magnitude in complexity than finding a new life cycle methodology. Not only will the impact of a new word processor be minimal compared to a whole new methodology, but the products themselves will be substantially simpler to consider. On the other hand, there will certainly be a tremendous number of word processors available on the market compared to life cycle methodologies. You must allow enough time to perform a reasonable survey for even the most minimal change. Truly, the bottom line is that no matter what type of product you are searching for, the amount of time required or the approach taken will not substantially vary.

In Chapter 1 we discussed the pros and cons of acting solely on your own initiative versus enlisting management involvement from the beginning. During the selection phase, there is no compelling reason that should direct you to alter your decision in either direction. The guidelines discussed in the last chapter remain applicable; soliciting management support will be dictated by a combination of your unique situation, your organization, and your management. However, if your management is aware of your efforts or possibly even directing the process, a due date may well be predetermined. Moreover, it is highly probable that you will be given more time than we are recommending for this phase. If that is the case, exercise restraint, complete the survey within two months, and pleasantly surprise your management.

If you are given a mandate to compress the survey into less time, you should seriously examine the possibility of complying. If this does not appear to be a viable alternative, then you must present your management with a list of activities to be performed during this phase so that they can appreciate that you do indeed need more time. In the next section we will discuss the specific activities that comprise this phase. However, before we move to this topic, we need to recap some salient points about setting the due date:

• Due to the rapidly changing environment of data processing, time allotted for the selection phase should not exceed two months.

• The complexity of the product for which you are searching will not cause the amount of time to vary substantially.

• If you are acting under management directive and are given many months for the product search, you must still limit the time to two months.

Finally, whether you are working with your management or alone, you must establish a time frame to which you are truly committed (publicly or in your mind only).

Performing the Market Survey

Now that you have a target date, you must begin the concrete tasks of candidate product selection. These tasks are truly so simple and straightforward that they may seem at times almost childlike. The first thing you should do is gather as many trade journals as you can easily obtain. Don’t visit every computer store in the state; approximately 8 to 10 major magazines or journals are more than sufficient for almost any product category. Next, you will spend no more than two or three days surveying the literature for products you will investigate.

You will want to keep track of all products that you consider. It does not matter if you dismiss a product as a possibility a mere five minutes after it was brought to your attention; you still need a record that it was considered. This record will be useful throughout the selection process; it should be kept (as well as the detailed product information) as a source of historical background information in the future, when people may have questions about the process you followed.

A number of years ago, I was the project manager for the development of a UNIX system. Not surprisingly, one of the significant issues we had to address and resolve was selection of a Data Base Management System (DBMS). Both during and after the market survey, we kept extensive (not necessarily formal) records of all the possibilities considered. This modest effort saved us a tremendous amount of time and energy many times during the development of the system. As it turned out, the DBMS we selected was not the most prevalent or even a popular choice. Therefore, as the project proceeded, many people questioned the wisdom of our choice. Once we were called upon (at very short notice) to provide our director with information about all the products considered, as well as the rationale for our selection. Many of the casual inquiries were satisfied by the fact that documentation of the selection and evaluation process existed. However, some of the requests, such as those from technical support and operations, resulted in people receiving valuable information. In any case, whether requests are motivated by politics or true need for information, you will never regret the minimal investment you make in keeping track of your market survey.

How you might record this information is up to you: The level of detail, as well as how formally you document this phase, is extremely flexible. If you are operating on your own and are pressed for time, a simple list that contains all products, vendor names, addresses, and phone numbers, in addition to reason for exclusion from or inclusion in the evaluation phase, should be sufficient. If months later (when your implementation is successfully proceeding), you are questioned about this phase, it will be viewed as a miracle that you kept any records of all.

On the other hand, if this is your full-time assignment, you will probably be expected to provide your management with a report at the end of this phase. The contents of the report as well as the format will vary from one organization to another. Some groups with which I have worked were satisfied with the information described above, while others required a matrix where the columns and rows were dictated by local conventions. Some PC-based products such as Lightyear support this process, and may even remove some of the subjectivity by allowing you to specify weighting factors to predetermined selection criteria.

The Vendor Relationship

After you have selected some products that indicate promising features, you will spend a few days calling each vendor to request detailed product information. The importance of these phone calls to you as a change agent cannot be minimized, because this is the beginning of a very important and useful business relationship. After all, the vendor of the product you ultimately recommend will be supporting your efforts during the entire implementation of your productivity improvement.

But even though these phone calls are important, you should not be at all hesitant about contacting numerous salespeople, because the overwhelming majority of vendors will be extremely cooperative. Moreover, even though they may view you as a potential customer, most will not be overtly aggressive. If you should encounter difficulties with a vendor, this can only be viewed as useful information. For example, if a particular person with whom you are dealing is very uncooperative, you should consider that individual a representative of that vendor. Then when you are making your selection, you might wonder about the quality of support you will get after you purchase the product. (We will address this possibility in detail when we discuss the evaluation phase in the next chapter.)

On the other hand, you must ensure from the very first conversation that you also treat each vendor contact forthrightly and with respect. For example, you must make it very clear that you are performing an investigation only at this time. You want the salespeople with whom you will be dealing to understand clearly that you do not want to incur an expense at this point and that you are not interested in discussing contracts or licenses. You do, however, want price information included with the brochures they send you. There is absolutely no benefit or even need to act as though a major purchase is imminent when it is not. That you represent a potential customer will be evident to any responsive salesperson.

Actually, basic honesty between yourself and your vendor contacts is the only viable option in the long run. I had a friend who worked for a major corporation and was quite boastful of his prowess in the arena of vendor manipulation. He was taken out for many free lunches, provided with expedited service, and loaned products with no associated charge. These interactions proceeded until it became obvious that a purchase was not forthcoming. Approximately a year later, my friend had a different assignment in which it would have been quite beneficial to incorporate the vendor’s product. Although he complained bitterly about the vendor’s decline in responsiveness, it was no surprise to us that his phone calls were hardly ever returned.

Since you of course will conduct yourself in a reasonable manner, most people will respond accordingly, be very helpful, and soon swamp you with brochures and price lists. As soon as you have any information at all, you must begin analyzing the individual products in relationship to your organization’s requirements. Remember, the goal is to narrow the products down to a few possibilities that someone will evaluate in detail. Moreover, you must by this time have the requirements firmly determined.

Before we proceed with requirement formation, let’s summarize the steps you have taken thus far:

1. A date has been set that will end with the selection of candidate products.

2. You have surveyed the market for available products.

3. Your survey has been recorded for historical reference.

4. You have contacted the vendors of the products.

5. Detailed information, including prices, is on the way.

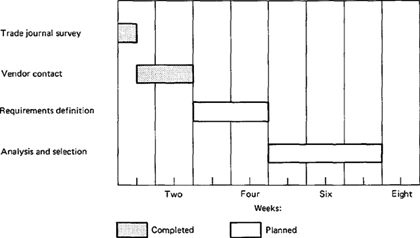

Note how much has been accomplished, and yet you are only on week 2 of the time allotted (see timeline in Figure 2–2). This fact may give some credence and even comfort to the thought of allowing only one to two months for this phase.

Figure 2–2 Typical Time Required for Selection Phase.

Defining the Requirements

It is essential that you perform this step at this juncture: The chances of any product having every feature that is on your requirement list is extremely slim; however, if you do not know precisely what you want, an undesirable scenario may unfold. As you examine products and find some that are quite good, you may unconsciously keep expanding the hazy picture of what you want. Indeed, this scenario is a classic case of the “chasing the rainbow” syndrome described at the beginning of the chapter.

In order to understand how very easy it is to slip into this syndrome, let’s reflect on the following story. Imagine you are selecting a new data base management system (DBMS) for your department. You have eagerly accepted (or initiated) this challenge and have thoroughly enjoyed your market survey. During your analysis of the product literature you find a very promising DBMS; it is relational, compatible with your current hardware/software environment, and reasonably priced. You should now proceed to the next phase for an in-depth evaluation; but when you think about it, you wish that the DBMS supported a screen generator. So you search further by analyzing the product literature again, or you may even resurvey the market. Eventually you find another product that seems to have all the qualifications of the first one, including the screen generator. However, instead of proceeding with an in-depth evaluation, you start looking for a product with an on-line help facility.

It is not hard to believe that you can easily fall into this trap; nor is it hard to imagine that you will never find a product that fulfills your need (which is constantly expanding), and that you might indeed search forever (see Figure 2–3). On the other hand, if you had clearly defined your requirements, you could have rapidly compared these requirements to each product as you received detailed information about it.

In the ideal situation, requirements would have already been analyzed and documented by you or others, and this situation is actually not as unlikely as it might seem. I know that this can happen because when we implemented a CASE tool, that was exactly the situation. For a variety of reasons, very difficult times had come to our organization, and morale was very low. Upper management had commissioned a task force of middle managers to assess the situation and come up with a recommendation for relief. They thoroughly evaluated all the circumstances and clearly identified a need for analyst support to improve the following phases of the software development life cycle: user requirements, system definition, and logical design. A group of analysts was chartered to develop and document the requirements for a new system that one of the project teams would then develop.

The requirements document had been completed, but due to funding considerations, development of a new system was not a possibility. A year later, when we were searching for a CASE tool, my boss (who had been one of the middle managers on the task force) utilized this document during the process that resulted in our selection of Excelerator. There is, of course, an obvious moral to this story: Neither you nor other change agents may have been part of any effort that resulted in requirements being developed. However, it may well be worth investing a small amount of time investigating the possible existence of any remotely related material. As an agent of change you will be constantly racing against time, and thus there is absolutely no advantage in redoing any work already completed.

Figure 2–3 Chasing the Rainbow.

If you are not so lucky, then you need to document a set of well-developed requirements before you proceed with the analysis of the product literature. It is not at all necessary that this document be a formal one, particularly if you are operating on your own. Of course, if your management is involved, they may have some very definite requests that you will have to satisfy. In any case, bear in mind your time constraints and by all means keep it as simple as possible. We have employed a technique as primitive as listing user requirements and then organizing them into bulleted items by category. The critical aspects of this activity were to determine clearly in our own minds what was required, document this information (formally or informally), and then utilize the document as a reference during the analysis.

When you are documenting the requirements and analyzing each product, keep the following three points firmly in mind:

• Who your users are and how this product will improve their work lives

• Never getting stuck on a particularly snazzy product

• Ensuring that the benefits are not obscure

Employing Empathy

The first objective is to determine what will truly benefit your users. You do not ever want to introduce a management method to control, which becomes a burden to them, but rather a product that will truly add something to the work process. This determination is a critical success factor, because if you do not truly add value, then you will never gain the acceptance of your users. After all, they are intelligent professionals who are so busy they are already stretched to their collective limits. Thus although it is safe to assume that none of us would ever intentionally select a product that does not really benefit, it is still quite possible that we might inadvertently do so. The art of ensuring that this is not the case relies heavily on employing the skill of empathy.

Empathy is defined as identification with and understanding of another’s situation, feelings, and motives, and is really an ability to step back and imagine yourself in the place of another person. For example, suppose you are searching for a project control and tracking tool. The average project manager is overworked and behind schedule, as you can probably quite vividly remember from your own recent experiences. When you were not dealing with dissatisfied users, you were probably explaining to your management why you were behind schedule, and trying to keep the programming staff on the right track.

As a change agent, you have just found a fantastic tool that will keep track of every activity and can generate graphs and reports by person or by day or by activity. However, the only way to ensure accuracy is for the project manager to personally spend a half-hour every day inputting data. Can you really imagine a positive reaction from your potential and exceptionally busy users? It might be a different story if we were talking about a startup problem. In that case, there would be some initial obstacles to overcome, but you could imagine yourself (and thus your users) eventually accepting and even welcoming such a product. Moreover, it is highly likely that the project managers would welcome and appreciate a tool that does a little less, but requires no additional effort from them.

In general, people are very busy, and they don’t view anything new as positive—especially if it is going to require considerable training initially and then require them to perform extra job functions. You may not have to convince anyone at this stage except yourself, but if you are going to be successful at implementing change, you will have to convince many people. Just imagine yourself doing their jobs, and avoid anything that might add extra and annoying steps to their already hectic days.

Avoid Razzle Dazzle

You also must avoid selecting slick, exotic products. Never forget that due to our technical backgrounds and propensity to leading edge products, we are quite susceptible to marketing hype. Moreover, it will appear (and rightly so) that razzle dazzle will substantially assist us when we are presenting the tool, but may well be counterproductive during and/or after actual implementation. Suppose you found a word processor that operates very impressively on a color monitor; and you even have the option of selecting among shades of green, red, etc. Furthermore, when you bring up this word processor, it generates a picture of a user and then a terminal. The user walks over to the terminal, turns it around to face you, and the product’s logo leaps out and covers the screen in brilliant color. This product would capture the attention of even the most jaded and cynical. Images of yourself demonstrating this tool to your director or even the vice president fill your mind. Months pass, and you are now dealing with some harsh realities. It turns out only 10% of your users have color monitors. Moreover, everyone, including yourself, is fed up with the user, the terminal, and the leaping logo, which takes up a considerable amount of time whenever you want to use the product. This is a striking example of the seduction described at the beginning of the chapter. You must never let go of your practicality when you are examining potential products, because you as well as your users will have to live with your choices for a long, long time.

The Right Product for the Right Organization

One final caution we might offer is that you must also ensure that the benefits of the selected products will be reasonably obvious to the people in your organization. In Chapter 1 we described several methods for assessing your organization. Therefore, you have surely and correctly selected a target area where there is a real need for improvement and where the gains will be substantial. However, if you find a virtually perfect product, but to most people none of its benefits are recognizable or it requires years to realize the benefit, you will find it almost impossible to convince your users and management.

Timeliness of your implementation is critical and will be discussed thoroughly in Chapter 8. But the other aspect of enabling your users and management to perceive the benefits is related to the modality of your organization. Every department (and to certain extent even an individual work group) very rapidly develops its own general pattern of operations. There are unspoken sentiments that affect most daily interactions and that include a set of collective priorities. For example, it may be clear to you the business planning methodology that you have selected will substantially improve the quality of the systems being developed by your organization. However, it is a fact that these people have a very informal approach to the software development life cycle; i.e., they really only want to code programs. The current mode of operation here barely addresses design, and thus you can be sure there will be zero interest in planning.

The benefits of even the most perfect business planning methodology would be virtually impossible for this group to comprehend. Furthermore, if by some miracle you were able to begin implementation of this methodology, you would initially be changing the very beginning of the project’s life cycle. Since these people are into the code, it will take months or even years to realize some concrete results to which they can relate. Because this organization is into instant gratification you would have a higher chance of success here with a programmer productivity tool, such as a code generator. It is crucial to realize and accept that in addition to providing a product that truly adds benefit, your users and management must also be in a position to appreciate this benefit.

The selection phase is fraught with many potential and even seductive pitfalls into which a change agent can stumble and remain for a very long time. This is probably more true for this phase than many others due to the combination of tasks involved and our predisposition toward technology. However, you are now armed not only with a well marked trail to follow, but also which attractive but dangerous paths to avoid. Therefore you can confidently enjoy the aspects of product selection that are so attractive without being seduced into remaining there forever.

Summary

• To ensure successful completion of this phase, you must limit both the time and the scope of your market survey.

• Although the products for which you are searching may vary considerably in complexity, the time allotted should not exceed two months.

• During this phase you will set the tone of your vendor relationships. This is very important because you will be dealing with one of them for the entire change process.

• Before selecting any product, you must clearly define the requirements so that you do not risk the possibility of searching forever for the perfect product.

• To assist you in requirement formation, use empathy, avoid razzle dazzle, and base your selection on the modality of your organization.