14

Finishing the Implementation: Handling Success

You are now approaching the final stages of finishing the implementation, and although there remain a few tasks for you to perform, primarily your job is completed. You set out on a crusade several years ago; you have passed safely through all the phases of the change process; your effort is totally secure; and you have spent the last year finishing up your mission. You have gently yet unswervingly persisted in your attempt to improve productivity; you have averted several potential disasters; and you have stabilized the situation. The present reality includes a steady increase in usage of the product by the converted and conversion of the uninitiated.

The main caution we offer at this juncture is: Do not become complacent. You may have told your story countless times, but you will still have to give your sales pitch on a regular basis. Moreover, even though you have attained substantial influence and power, you must cherish your original service orientation. Retain some humility; remember how very many people actually did participate to make the present environment a reality.

Remaining Objectives

As a matter of fact, it is likely that there are some objectives still to achieve. For example, when we were at this very point in our data management implementation, we still had not assimilated our remote users. To provide some background on this problem, let me describe what I had perceived as one of the fundamental reasons that historically had impeded effective data management in my organization. Namely, our department spanned four separate geographic locations; three of the sites were in the same state, but hundreds of people were thousands of miles away. This substantial distance heightened the usual communication problems associated with the development process, including data management. Our hope was that with an integrated dictionary, electronically accessible to all users, we would be able to compensate for some of these difficulties.

However, our entire implementation approach had been based on utilization of the informal network and hence had consisted of numerous casual, steady social interactions. Therefore, the distance itself had hindered our ability to make any substantial progress in the case of our distant users. We had always been so busy, even during the uneventful phases, that this aspect of the change process had been relegated to the backs of our minds. At this time, though, there was little left to distract us, and we had to face the fact that this was a genuine problem. How we solved it was simple and should have been obvious to us months before. We used the exact same techniques that we had utilized throughout the whole process: We provided information to raise awareness, we listened effectively, we made ourselves available to help, and we held strategy meetings. We began by making a point of visiting our remote users at their location every two weeks for several days at a time.

The first trip we made was not the most pleasant; these users, like all other data processing people, were very busy and not particularly interested in promises of future relief. Since we did not really know any of them personally, there was no resource available to help us with any procedural red tape. For example, we had to make all the arrangements (for meeting rooms, food, etc.) through a centralized conference planning group. Ordinarily, all the phone calls associated with something like this would have been made by one of their secretaries. It was not so much that a major effort was involved, but that it was a sign we were not truly welcome, and that was discouraging. Since people were not all that interested in dealing with us, we did capitalize on some of our newly acquired influence and power. We wrote a memo explaining our function in the organization and our reason for being there. Our management wrote memos to their management requesting cooperation and support. We had our meetings, which were not dramatic in any direction; and we persisted. Finally, by the third trip, although we were by no means close to acceptance, there were some concrete signs of interest. By casual interaction, perhaps something as minor as spotting a screen layout on somebody’s desk and offering the information that it was already in our dictionary, we were able to illustrate how we could make life easier. After a few months, we knew our objective had been achieved because they presented us with our own office!

It was also during this time period that we recruited a technical guru into our group, and we were finally in a position to complete our physical implementation. You may recall from Chapter 12 that following our reorganization to the planning division, this work item was relegated to the bottom of our priority list. Its placement was due to the following facts:

• There was a notable lack of resources in terms of people with technical skills available.

• We were dealing with at least a dozen more urgent and critical work items.

• Our users had, in fact, been surviving quite adequately without a local area network.

Common sense dictated that this item could certainly be postponed until there was a more favorable set of circumstances. Now we were finally able to address items such as these, and our own perception of our situation was less constrained. The days of merely trying to ensure the survival of the change process were so far behind us that adding luxuries was now a real possibility. Our technical guru proceeded to implement STARLAN which was impressive enough to be used as a model for other data management groups. In fact, since it consisted solely of our corporation’s hardware and software, we actually shared our solution with marketing and selected members of the sales force.

Since you will now have more free time and energy, it will also be possible to provide some additional customized services for your users. In Chapter 9, we described a friend’s use of templates during the implementation of Project Workbench. When he arrived at this final stage of his implementation, he extended the concept even further. Not only did he supply each project manager with a template containing all phases and activities of the methodology, but he included a template for the resource spreadsheet he individualized for each project. He prepopulated PW with the names and availability of each person involved, as well as the cost of their labor or their daily rate (see Figures 14–1a and 14–1b).

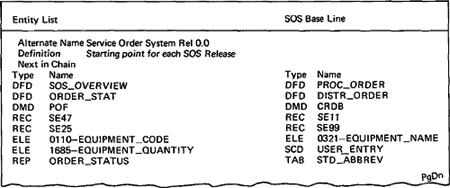

We provided a similar service for our Excelerator users at this point in our implementation. Although we had instituted version control much earlier in the change effort (see Chapter 9), this was a manual process. At the beginning of the definition phase, we would meet with the project team and jointly determine exactly which records, elements, screens, reports, and data flow diagrams would form the basis for the next release. We mechanized this process by utilizing the entity list feature of Excelerator. Entity lists enable you to create (and retain) a group of unrelated items that can be used as the basis for some other activity such as sharing data with other users. Therefore, we created an entity list for each project that would serve as the starting point for each release cycle (see Figure 14–2). Of course, since each release was unique, they invariably had to be modified; but there was always a subset that was constant, so considerable labor was saved.

Figure 14–1a The Sample Template Provides Information About Each Group Member’s Availability (i.e., 5.0 days per week).

Figure 14–1b This Companion Report Provides Additional Information on Daily Rate (e.g., $450 per day for Adam).

Figure 14–2 This Sample Entity List Could be a Basis for Every SOS Release.

Naturally, this part of the implementation will be no different from all the earlier phases in the sense that you will continually encounter challenges. However, before we proceed with our discussion, let’s list some of the activities you will be performing during this period:

• Completion of objectives that are unpleasant, or not critical, and thus have been artfully ignored, such as our assimilation of remote users

• Attention to tasks that were not essential and consciously relegated a low priority, such as our establishment of a LAN

• Time and energy to expend on luxury items, such as resource spreadsheet templates for Project Workbench and Excelerator entity lists for new releases

• Avoidance of complacency and overutilization of newly acquired political power

• Retention of some measure of humility and continuity of approach

Burnout

One of the major challenges that will arise at this time is associated with the unending condition of the change process itself. As we indicated at the beginning of this phase, it will never end, and therefore boredom is inevitable, because the process has become monotonous. There is a limit to the number of users you can train, strategy meetings you can hold, and times you can sell upper management. Change agents can suffer from burnout just like other data processing individuals. It may not be from 80-hour weeks, but rather from the tedium that has begun to be associated with the job. It is, nevertheless, burnout. In fact, it is the very personality of a change agent that will make this situation so unbearable. You are a person who set out to move mountains, and indeed you did. Although when you began, you may not have realized you would do it a shovelful of dirt at a time. In any case, chances are excellent that you are not the type of person who is content when things are peacefully meandering along.

We, not surprisingly, do have some observations and suggestions to share about this inevitable dilemma in the life of a change agent. The real source of the dilemma is that you have been the critical success factor in this whole process; you were from the beginning to the end the one aspect of the implementation that was absolutely essential. It was your assessment of need and firm conviction that began it. It was your knowledge and enthusiasm that sold it. It was your foresight and organizational insight that planned it. It was your drive and your patience that implemented it. It was your dedication and persistence that completed it. Thus, it will not be readily apparent to your management that you are not only restless, but actually no longer essential.

Redefining Your Role

One way you can master this particular condition is to redefine your role. After all, you were the one who created it in the first place, so there is no real reason why you cannot be the one to modify it. The most straightforward way for you to achieve this objective is to expand the scope of your acknowledged function. This is precisely the technique we used in both the data management and Excelerator implementations. In the Excelerator case, we expanded our role to incorporate other tools, such as Project Workbench. Since we were supporting the development process in terms of analysis, it was a natural extension to assume the responsibilities of project planning, control, and tracking.

At first we did meet with some resistance. Our current manager was apprehensive that this expansion of our role would in some way jeopardize our effort. In fact, he held this view so strongly that even the polished and sophisticated salespeople that we had become could not convince him. We were forced to postpone this new role until we were reorganized again. Happily, the next management team was tremendously supportive of our concept of the “integrated developer tool kit.” This did precipitate a small flurry of jealousy from some of our peers, but surely we knew the art of overcoming resistance at this stage of the process. In addition, at that time the two vendors were pursuing a seamless interface between their products, which had some implications for us. In particular, the marriage of the two products did lend credibility and support for our newly expanded role. We were invited to and did participate in a planning forum sponsored by both vendors, which did indeed bring some excitement back into our lives as change agents. We were actually afforded the opportunity to provide significant product direction for some of the tools we had been crusading for years to incorporate into everyone’s daily work life.

Before we share some additional problems that change agents may encounter during the final months of the process, let’s pause and summarize:

• One of the major problems is related to the fact that the change process is unending, and thus boredom is an inevitable consequence for change agents.

• Since you as a change agent have been from the very beginning a critical success factor, the fact that you are no longer essential will not be evident.

• One way to cope with this dilemma is to redefine your role.

Interacting with Corporate Groups

Another problem you may experience is some less than positive interactions with various corporate groups. This will vary depending on the quantity and quality of your interactions with them up to this point. If you have had regular information exchanges and have been following their lead, you should not have too much trouble. However, if you have been operating primarily on your own, by the time you come to their attention they may have numerous opinions to express. In either case, since you are in the process of expanding your role, there is a real possibility that intense jealousy (on your part as well as theirs) will enter the picture. But ultimately you must cooperate with these people and establish a reasonably positive relationship.

When we implemented Excelerator, although we did not consciously elect to operate without guidance from our corporate methodology group, that was exactly what occurred. About a year into our implementation, we made our initial contact with them; needless to say, we did not start out in their good graces. They were actually reasonable people who were very competent in their jobs, but the modality of their organization was entirely different from ours. We began our interactions with a series of miscommunications, which resulted in suspicions growing on both sides. They ultimately did give a blessing to our effort, but it took many months and expressions of gentle goodwill on our side to improve our starting position. Once we became better acquainted with some of them, we were also better able to appreciate their viewpoint, and our own resentment abated somewhat. We never did establish a totally positive relationship, but we did arrive at a manageable one.

You must include the corporate groups at some point in your change effort, and you should not be hostile toward them; after all they are just trying to do their jobs. However, timing can be critical. If you involve them too early in the process, they may ensure that your effort is brought to a halt. They are policymakers, and so their timetables will not be as urgent as your own; it is possible that they will advise you to wait months or even years while they study the situation. However, we do not want to imply that their involvement will always be negative. Remember the potential value of their contribution in terms of coordinating employee data across systems (see Chapter 3). You may also recall that when we implemented data management, the corporate standards groups with which we dealt were reasonable and flexible (see Chapter 9). Don’t assume that the interactions will be either positive or negative; consider the mentality of your own corporate groups, the extent of possible delay, the urgency of your productivity improvement, the risks in all directions, and then carefully select your moment.

Before we proceed with a discussion of involuntary role expansion, let’s recap your group’s potential interactions with corporate groups:

• There is a real possibility that as your role expands, your group will clash with various corporate groups.

• You must establish a reasonably positive relationship with all corporate groups.

• This positive relationship will be gained via the same techniques you have applied throughout the entire process—gentle and polite persistence.

• You should attempt to empathize with their perspective and do not prejudge their contribution (or the lack of one).

Involuntary Role Expansion

During this period, you may also find your role expanded without any conscious effort on your part. In Chapter 11, we described the elaborate workshops we were offering near the end of our Excelerator implementation. The scope of our training services was communicated quite extensively via the informal network of our attendees. Since we maintained our commitment to cooperation and we valued the extension of our own informal network, we did not limit the workshops to our own users. The result was that we trained people from all over our corporation, gained tremendous visibility, and enjoyed the diversity of our new acquaintances’ experiences with the tool.

We also enjoyed some very interesting experiences at the corporate level during the final phases of our data management implementation. As our implementation became more and more a reality, it attracted a reasonable amount of attention. We had many opportunities to participate and provide input to assorted corporate activities. In reality, some of the experiences were more in the category of endurance than enjoyment, particularly those that involved task forces. Our experience indicates that once you become a successful change agent, task force participation or similar activities will require a steadily increasing percentage of your time. We will describe in considerable detail some of the generic difficulties they cause, along with some coping techniques we have employed.

We can certainly all appreciate the significance and importance of gathering people together from dissimilar functional sectors of a company to accomplish a specific task, because there is a similar motivation that drives the formation of the project and interproject teams. However, there are some fundamental differences between task forces and project teams. Task forces are assembled for a specific purpose for a limited amount of time, and there is always an element of urgency. This urgency impedes the formation of a team because there is no magical overnight method for its creation. When the interproject team was being organized (see Chapter 7), considerable effort was expended by the team leader during and between meetings to forge the bond. In reality, the establishment of this team bond is a gradual process, and requires commitment, patience, and persistence on the part of the leader. In the case of the task force, the luxury of time is not an option, and so the gradual process of team building is also not an option.

A further complication lies in the fact that people invariably bring to the task force extreme organizational biases. The organizational pressures are more severe than under ordinary circumstances, because the results of the task force will probably have a profound impact on all the involved organizations. Moreover, there is considerable pressure to produce a useful deliverable quickly. These two facts tend to cause substantial conflict for task force members who must reconcile corporate objectives and their organizational allegiances. Finally, the fact that you must be away from your regular assignment for an undetermined amount of time tends to promote frustration even before the first meeting. You will have to arrange for your group to be managed while you are absent and then somehow ensure that it is managed well. All these factors foster an atmosphere of relentlessness and intensity in task forces that always made me classify them as cruel and unusual punishment.

How do you deal with this fairly unpleasant situation that you as a successful change agent are likely to be in more than once? In relation to the team issues, you must attempt to promote a team bond; in this case, however, you will not be the leader, but rather a participant. You may not find this role altogether comfortable. After all, as the principal change agent, you have been in charge of things for quite a while. Now, instead of directing an effort, you are being asked to participate in it. The first step toward achieving this goal is to recognize and accept this role as the capacity in which you will be serving the task force. Once you adapt yourself, you might find the experience quite pleasurable. Consider the activities that have become boring that you will not have to perform, such as selling and teaching. All you have to do is effectively listen, evaluate what is happening (interpersonal dynamics as well as events), and when necessary contribute. It is another matter altogether to address the political realities, such as serving true corporate need while adequately representing your own organization. Personally speaking I always harbored the fear that upon my return my management would demand accusingly: “How could you have let this happen?” It was never clear to me whether the accusation was because the product of the task force was mediocre or because our organization’s interests had suffered. In either case, I was convinced there would be trouble. So what is the solution? The secret lies in remaining truly open-minded.

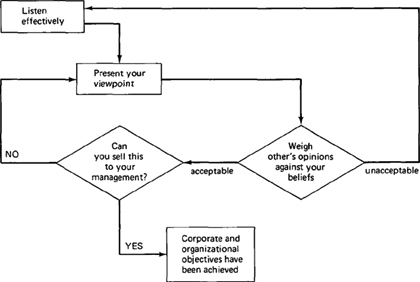

Being open-minded involves utilizing both communication skills—listening and speaking—plus an additional ingredient. You must listen effectively, present your point of view, and then carefully weigh what is being said against your own beliefs. This is never easy for us, because it causes some internal conflict; it is even more difficult when we are also being influenced by politics. It is so much simpler to doggedly hold onto our organization’s viewpoint by convincing ourselves that this is our own view as well as the right one. (People will often stubbornly retain a position in the face of overwhelmingly contradictory information.) However, what you must do after you have listened to all points of view is to weigh each one against your own experience.

The result will be the solution to the dilemma, but you are not quite finished yet; you must also evaluate your organization’s reaction to it. If you cannot sell the result to your management, then you must attempt get the group to modify it enough so that it will be acceptable to your people. Remember in this situation “buy in” is an objective for the task force leader, just as it was for you with your interproject team. It will therefore most assuredly be an objective to assist you in your desire to gain your management’s acceptance. Figure 14–3 provides a road map of the process.

The final hardship is that task force participation taxes your ability to be a good manager. This ability really calls for the application of two techniques; keeping your group going and keeping your management informed. Keeping your group going from a distance is not as troublesome as you might suppose. You should leave your most trusted and dependable staff member in charge. This individual is not necessarily the one with the most seniority or experience. Don’t worry about selecting the right one either, because you have had substantial experience in sizing them up for different functions (see Chapters 3 and 12). Then ensure that you can always be reached in a crisis. Furthermore, you will call regularly in order to maintain the group’s team bond. This act of connecting is similar to one of the techniques you used to maintain the interproject team bond between meetings. Finally, avoid fretting about what is happening (or not happening). Even if the situation becomes truly muddled, you can sort it all out upon your return.

Figure 14–3 Being Open-Minded will Ensure the Success of the Task Force.

To keep your boss informed, you should utilize the same techniques: ensure that he can reach you, and call him regularly. In addition, it is usually a good idea to send memos that serve the function of task force status reports from your perspective. Include the events that have taken place, the areas addressed by the task force that you feel comfortable with, and anything that is a major concern to you. In connection with sharing concerns, we are not suggesting hysteria. There may be an area where you are dissatisfied with the group’s decisions and you eloquently shared your concerns. If the group members refuse to alter their plans, there is no advantage in keeping this to yourself. Your boss may respond with some very specific instructions, such as ignore this issue or resurface your concerns resolutely; or he may ignore the issue entirely. In any case you have expressed yourself formally for the record, and you have not disrupted the group’s efforts by dwelling on this item.

Since involuntary role expansion will undoubtedly increase as you become a successful change agent, let’s attempt to distill some of its most significant aspects:

• As you become successful, you will find yourself involved more and more often in corporate activities such as task forces.

• Task forces bear some similarity to interproject teams, but the gradual building of team bond is seldom possible in the task force situation.

• You can contribute to the establishment of a team bond by recognizing that you are not the leader but a participant and utilizing your acquired skills (e.g., effective listening) to be useful in this role.

• Every participant must resolve the conflict of serving true corporate need while adequately representing the needs of their own organization.

• In order to reconcile this conflict between corporate and organizational goals, you must be open-minded.

• Another hardship caused by task force participation is the difficulty of being a good manager in absentia.

• To ensure your group’s well-being while you are away, remain accessible to your delegated authority and your manager, and also contact them regularly to maintain the group bond.

The End of the Road

We have just about come to the end of our journey down the road of productivity improvement. As a final example, we would like to share the story of how we handled the change agent burnout dilemma in our data management implementation. We were at the point where our data was finally under control; no new aliases were being created, and in fact no elements were being added, deleted, or modified without first being analyzed by my group. We were considering various ways to extend this control into the software itself, when a programmer suggested a feasible way for us to proceed. The recommendation was to repeat the same process we had employed in gaining control of our logical view of the data—namely, to begin changing the physical reality with the interfaces, which was the least complex, and work gradually toward the problems that would be involved in changing IMS databases. Not only did I consider this a brilliant suggestion, but I was overjoyed at concrete evidence of the extent that we had succeeded in overcoming resistance. How many times can any of us boast that we have precipitated a programmer’s actually volunteering to modify code? However, we did not proceed with the recommendation, although we seriously considered it. We decided the effort was just not worth the result. This was the very moment when we brainstormed our way to the modern data architecture of a conceptual data model and the subject databases. We reached the vision of a more proactive role; we did not merely want to administer the data, but rather to shape it into a stable structure that would accurately reflect our business needs.

I placed my most promising acolyte in charge of this effort, and the plan unfolded. We would follow the same steps we had taken to implement data management; that is, we would proceed with every phase of the change process from the beginning. We had already assessed a need—namely, our basic architecture was unstable because each system had its own version of the same data. What was required was not an SOS database, an ERS database, etc., but an employee data base, a customer data base, etc. The next step would involve an evaluation, which would include a business case. Then the marketing phase could begin. My protege would have to sell upper management as well as the potential users. There would be a period of information gathering, during which the new change agents would listen, analyze, and brainstorm their way to an approach. The planning phase would cry out for an interproject team to develop a migration strategy and schedule. The programmers would offer the technical guidance; the systems analysts would schedule (nondisruptively) their recommendations into planned releases; and the strategic planners would keep everyone informed of possible future end user needs and factor the proposed migration plans in with end user priorities.

I had chosen my successor, and began preparing her to be a missionary on this new crusade. I started my search for the next role I would assume as a change agent. When the effort was well underway, and our management had a high degree of confidence in her and in this new productivity improvement, I proceeded to my next crusade.

Summary

• Although you are nearing the end of the change process, you cannot become complacent. Work items that had a low priority still need to be completed.

• You can also make use of the free time and energy to provide some additional customized services for your users.

• The major problem that will arise at this stage is the change agent’s burnout. This phenomenon is associated with the unending condition of the change process itself.

• The personality of the change agent will undoubtedly contribute to the burnout, but can also be utilized to reshape his or her role.

• The redefinition of role may be accomplished in several ways (e.g., incorporation of new productivity tools) and may in some cases even be involuntary (e.g., task force participation).