2 Lal Lal Falls Scenic Reserve by Ian D. Clark

Lal Lal Falls near Ballarat in Western Victoria evolved over 162 years from an Aboriginal cultural site into a recreational and tourism attraction. Key moments in this history were the visit by two European Port Phillip Aboriginal Protectorate officials in 1840, the reservation of the site as a public park in 1865, and the tragic death of two school children from a landslip at the site in 1990. To understand the history of Lal Lal Falls visitation, this study uses perspectives developed by MacCannell (1976), Butler (1980), and Gunn (1994). MacCannell’s (1976) research into the development of secular attractions through five stages – sight sacralization or naming, framing and elevation, enshrinement, duplication, and social reproduction – will be tested to see if it satisfactorily accounts for the development of the Lal Lal Falls attraction. Butler’s (1980) tourism area life-cycle model may explain the subsequent stagnation and decline of the attraction, particularly since the 1990 catastrophe. Gunn’s (1994) spatial model of attractions should be able to add a spatial dimension to understanding the history of recreation planning at Lal Lal Falls in terms of three zones (nucleus, inviolate belt, and zone of closure) of visitor interaction outlined by the model. This chapter extends earlier research by Clark (2002) into the history of the waterfall.

The Lal Lal Falls are one of two falls found on Lal Lal Creek, a tributary of the Moorabool River, and is situated in the Parish of Lal Lal, and in the Moorabool Shire, three-kilometres east of Lal Lal township, and twenty-five kilometres from Ballarat (see Fig.2.1). The second waterfall on Lal Lal Creek is found near the site of the Peerewur Pastoral homestead.1 Lal Lal Creek joins the Western Moorabool River, approximately one km downstream of the falls, and travels another 300 metres before entering the Lal Lal Reservoir, which was established in 1972. The falls, formed when a volcanic basalt tunnel collapsed, cascade 34 metres to the pool at the base. The falls are situated on Pleistocene basaltic plains formed about 1.8 million years ago. The lava plain originated from Mount Buninyong (Land Conservation Council [LCC], 1980).

The Lal Lal Falls is situated within the traditional country of the Wathawurrung Aborigines, and is one of Victoria’s most significant Aboriginal cultural sites, as it is one of several recorded living sites of Bunjil – the Kulin peoples’ creator spirit (Bonwick, 1863; Massola, 1957, 1968, 1969).

The aesthetic appreciation of waterfalls and the spectacles they offer is a landscape taste that has existed in some cultures for over two thousand years (Hudson, 1998: 959). Waterfalls are not ubiquitous and Hudson (1998: 959) has suggested that as tourism resources, along with other natural curiosities such as caves, geysers, and glaciers, they have been neglected in the tourism literature.

2.1 First Phase: Sight Sacralization and Naming 1837–1846

In terms of MacCannell’s (1976) first phase in the development of attractions, that of ‘sight sacralization’ or ‘naming’, three Aboriginal names have been recorded for the falls – Bunjil, the creator spirit; Woringganninyoke, meaning unknown; and Lal Lal, said to mean ‘dashing of waters in a crevice’ (Clark and Heydon, 2002). An early historian of Ballarat, William Withers (1999: 4), claimed that the name Lal Lal had the following origin:

Before Mr Pettett took up the Dowling Forest run [in 1838] he was living at the Little River, and a native chief named Balliang offered to show him the country about Lal Lal. The chief in speaking of it distinguished between it and the Little River by describing the water as La-al La-al – the a long – and by gesture indicating the water-fall now so well known, the name signifying falling water.

Balliang was a clan-head of the Wathawurrung baluk, a Wathawurrung clan of the Barrabool Hills near Geelong, whereas the Lal Lal Falls formed part of the country of the Wathawurrung clan known as Tooloora baluk whose country encompasses Mt Warrenheip, Lal Lal Creek, and Meredith (see Clark, 1990). The name ‘Lal Lal’ appears to be a generic Wathawurrung word for waterfall, and is not the specific name of this feature, however; the word was sourced from another Wathawurrung speaker but wrongly conferred by Europeans.

Local historian Nathan Spielvogel claimed ‘Lal Lal, correctly pronounced “La-al La-al” was the aboriginal name for “the big crack” referring of course to the Falls’ (Mansfield, 1982:157); however, it is apparent that Spielvogel was unaware of the names recorded by Robinson in 1840 and 1846.

Europeans are thought to have first learned of the existence of the falls in 1837 when Frederick D’Arcy, a Government Surveyor, was working with his party on the upper reaches of the Leigh and Moorabool rivers, and was told of the falls by local Aborigines (Griffiths, 1988:1). D’Arcy was among a party of squatters in August 1837 that was formed with the purpose of exploring the Buninyong district. The party included Dr Alexander Thomson, George Russell, David Fisher, Captain Hutton, Thomas Learmonth, and Henry Anderson and an Wathawurrung Aboriginal guide possibly named ‘Darriwill’ (see Macqueen, 2010: 111f). They visited the Lal Lal Falls, only to find it was not running owing to the dryness of the season. George Russell, one of the participants, explained the context of the visit to the falls:

[In early spring of 1837 one of the government surveyors Frederick d’Arcy, who was sent to the Geelong district to survey the principal rivers and creeks and note remarkable objects] received information from the natives about a fine waterfall at the upper part of the Moorabool River, which the natives called Lal Lal. A party was made up in order to visit this waterfall and explore a little of the country round it … By arrangements we all met at Mr Anderson’s hut one evening, near Russell’s Bridge, where we stopped for the night; and we started for Mr d’Arcy’s camp.

We got on his dray-tracks, and after passing where Meredith is now situated arrived at the camp during the afternoon, and spent the night there. Mr d’Arcy having had an extra tent pitched for us. After an early breakfast we started for the falls, Mr d’Arcy having given his men orders to strike the tents, to put them and everything else on the dray, and proceed to Mount Buninyong, which was in sight of the camp, there to wait at the foot of the mount until we joined them.

After leaving camp we kept pretty close to the Moorabool river, following it up and passing through some rather thickly wooded and rangy country, reaching the falls about midday. But there was no waterfall. Owing to the dryness of the season the water had not commenced to run in the Moorabool, although it was late as the month of August. All that we saw was a steep precipitous rock, about eighty feet in height. I have since heard that the waterfall is worth seeing when the river is full (Brown, 1935: 158).

Withers claimed that ‘Before Mr Pettett took up the Dowling Forest run he was living at the Little River, and a native chief named Balliang offered to show him the country about Lal Lal. The chief in speaking of it distinguished between it and the Little River by describing the water as La-al La-al – the a long – and by gesturing indicating the water-fall now so well known, the name signifying falling water’ (Withers, 1870: 4). William Pettett was superintending at ‘Dowling Forest’ at Lake Learmonth for WJT Clarke from 1838. The D’Arcy version is sourced from one of the participants (George Russell); the source for Withers’ account is unknown.

This discovery and visit in August 1837 by at least seven Europeans suggests that these seven may potentially serve as the agency of the spread of news about the waterfall’s existence. The fact that it was not running when they visited, but they considered it worth seeing when the water was flowing, may have led to revisits by some of the individuals of this party, though there is no evidence for this. Qualifying the spread of information, however, is the local Ballarat newspaper editorial of 1857 (see below) that reports that the falls were not well known; so there appears to have been minimal word of mouth recommendation of its existence. Once the falls were incorporated into a pastoral lease, visitation appears to have been mediated by the lessee. The Lal Lal Falls formed part of Hugh Blakeney’s and Charles Ayrey’s Lal Lal Pastoral Run that they took up in early 1840. In 1843, Peter Inglis purchased the Lal Lal lease. According to Billis and Kenyon (1974), John Whitehall Stevens was lease holder from 1845-6; though there are no references to this in local histories. From 1846, Archibald Fisken, Inglis’ nephew, was given the management of Lal Lal, and eventually took ownership in 1854.

The falls were visited on 8 March 1840, by the Chief Protector, George Augustus Robinson, and Assistant Protector, Edward Stone Parker, public officers of the department of the Port Phillip Aboriginal Protectorate. The falls fell within Parker’s jurisdiction, the Loddon or Northwestern District. Robinson and Parker had spent the previous night at Charles Ayrey’s and Hugh Blakeney’s Lal Lal station. Robinson, in his journal, advised that Ayrey had told him about the falls during the evening and that he guided them to the waterfall. This confirms that Ayrey is the agency through which the falls became the focus of Robinson’s and Parker’s visitation.

Robinson’s account of his visit to the falls provides some confirmation that the name Lal Lal is not a local name, as implied by Withers. Robinson recorded Aboriginal names for Lal Lal Creek and names for both of the falls found on the creek. Robinson’s account of his visit is as follows:

Sunday 8 March 1840: A.M. Went with Mr Airey to see the fall of the western branch of the Marrabul, which Mr Airey informed me of the evening previous, about half of a mile from Mr Airey’s residence. This is the finest fall I have yet seen in the country. It falls a depth of 80 feet. The rock is basalt, the best formation I have seen in this province being pentagonal and distinctly marked. The sides of the ravine, as well as the head which forms the fall, are perpendicular; the S. side is concave, whilst the N. is short. The fall is quite abrupt. The channel along which the water from the surrounding country is brought to the fall is shallow, a mere hollow in the surface from which in wet season a considerable body of water discharges itself to the depth of 80 feet over the precipitous cliff which forms the head of the ravine. And then over a rapid a few hundred yards lower down. This fall in wet seasons must be magnificent (Clark, 2000a:199).

Robinson had recorded Woringganninyoke as the name of the Lal Lal Falls, and Nanden as the name of the little fall, presumably a reference to the much smaller fall upstream. The name for Lal Lal Creek was recorded as Yarkmyowing by Robinson. These names would seem to confirm that Lal Lal is a generic Wathawurrung name for waterfall.

Although Robinson in 1840 does not discuss the cultural associations of the site, Parker alluded to the existence of an Aboriginal legend in an article he published in the Port Phillip Herald after the March visit. The Port Phillip Herald article was reprinted in the Morning Chronicle (Sydney) (8 February 1845), The Australian (6/2/1845), Launceston Advertiser (14/2/1845); and The Sydney Morning Herald (3/10/1846). This article was republished in Braim’s (1846) history of New South Wales. Parker wrote, ‘Other traditions exist among them referring to the origin of certain natural objects. Thus they believe in the existence of another mythological being called Bonjil or Pundyil, who, however, is said to have been once a “black fellow”, and a remarkable locality is indicated as his residence when on earth. This is the deep and basaltic glen or hollow, forming the fall of “Lallal” on the Marrabool, near Mr Airey’s Station. He is now represented as dwelling in the sky, and it is curious that they call the planet Jupiter “Pundyil”, and say it is the light of his fire. This Pundyil is said to have found a single kangaroo, emu, and other animals on earth: that he caught them, cut them up, and by some mysterious power, made each piece into a new kangaroo, &c., and that hence the country was filled with these animals (Braim, 1846 vol. 2: 444-445).

According to Billis and Kenyon’s (1974) register of pastoral holdings, Robinson and Parker confused Lieutenant John Moore Cole Airey, at ‘Happy Valley’ in 1839-53, with Charles Ayrey who was with Hugh Blakeney at ‘Lal Lal’ during 1840-41; however, Withers (1870: 5) and Griffiths (1988: 5) identified Blakeney with George Airey, the brother of Lieut. Airey.

Robinson confirmed the falls connection with Bunjil when he visited the site a second time, on 7 August 1846, and this time the creek was flowing and water was falling. On this occasion Robinson did not stay at the Lal Lal station and he went to the falls without any guidance from local squatters, however, he was accompanied by a Djadjawurrung man named Merrigundidj who joined Robinson at the Mt Franklin protectorate station on 11 April 1846, and travelled with him from then until 8 August 1846, when he returned to the Loddon station. Robinson, Merrigundidj, and a border policeman named Patrick Farrell, went down the Murray River to Tyntynder station at Swan Hill and from there into South Australia where they visited the copper mines at Kapunda, the Native School in Adelaide, and returned to Port Phillip via Encounter Bay and Rivoli Bay and the Mount Rouse Protectorate station:

Visited the falls of Lal Lal, one which forms the gap large and the other part falls a height of [blank] width of [blank], was in all its glory worth seeing basaltic column rapid down another glen runs to it. … Natives call it Punjil, so Merryonedeet says, said [blank] belonged to it, was at Buninyong camp (Clark, 2000b:108).

Bunjil was also associated with a cave at Cape Schanck. Howitt (1845) and Bonwick (1863) both discuss this cave:

On this beach is the most remarkable natural cavern yet discovered in Australia Felix. … Altogether it is a wonderful cave. There is also as singular a tradition about it. As Pungil, the god of the aborigines, say the natives, was one day taking a walk on the sea, suddenly there came on a storm; when coming to the rocky shore, he spoke to it, and immediately, at his word, the rocks rose up, and this cave was fashioned before him. Into it the god stepped, and sheltered until the tempest was over (Howitt, 1845: 147-8).

James Bonwick (1863: 54), in discussing the Cape Schanck cave, also discussed Bunjil’s residence at Lal Lal Falls:

At Cape Schanck, of Western Port, a cave is pointed out from which Pundyil or Bin-Beal used to take his walks beside the sea. He was accustomed when upon earth to frequent other caves, chasms, or dark places. Deep basaltic glens were favourite homes. We are well acquainted with one of these assumed divine residences situated in a romantic volcanic rent some fifteen miles from Ballaarat, through which the river passes after rolling down the Lal Lal falls. The planet Jupiter shines by the light of his camp fire in the heavens, whither he has now retired.

Parker’s 1840 publication of the Aboriginal cultural associations surrounding Lal Lal Falls, and its republication in 1845 and 1846 should have ensured that information about the falls and its significance would be distributed wider than local squatters and their employees, and yet a survey of accounts of travellers to the district reveals that this does not appear to have occurred. Three accounts from travellers who visited the Ballarat district in the 1850s and 1860s (Clacy, 1853; D’Ewes, 1857; Snell, 1988) discuss the falls and only two directly visited them (D’Ewes, 1857; Snell, 1988). The Snell journal reference remained unpublished until 1988.

Ellen Clacy (1853: 133), learned of the existence of the falls during an 1852 visit to the Ballarat goldfields, but failed to visit them.

The country round Ballarat is more in the North American style, and when the creek is full, it is a fine sight greatly resembling, I have heard, one of the smaller rivers in Canada; in fact, the scenery round Ballarat is said to approach more to Upper Canada than any in the colony. The rocks, although not high, are in places very bold and romantic, and in the wet season there are several water-falls in the neighbourhood (Clacy, 1853: 133).

John D’Ewes visited the Lal Lal Falls in August 1853 during a three-month locum tenens appointment as Police Magistrate at Ballarat. During this time he took the opportunity to make excursions into the surrounding countryside ‘in search of picturesque scenery or sports, or the two combined’ (D’Ewes, 1857: 49). With reference to the falls, he wrote:

On the banks of a stream, was situated the pretty station of Lallal, belonging to a Mr. F….N, a thriving and hospitable squatter; near this station was a celebrated waterfall, which, in point of picturesque beauty, for its size, surpassed any I ever met with. The width of the first fall was not above 100 feet, with a sheer perpendicular descent of the same extent. The granite formation on each side was exquisitely beautiful, and so varied and delicate in its shapes and tracery that it might have passed for the handywork of some skilful artificer, as indeed it was, and the greatest of all – Nature! From this fall a succession of similar cascades appeared in a long vista, with an intervening space of several hundred yards between each, as far as the eye could reach. The deep clear basin at the bottom of each fall was full of a peculiar description of eel, some of enormous size, and weighing as much as ten pounds. On my first visit to this place I managed to scramble down the rocks with some rough fishing tackle, for the purpose of procuring a dish of the eels in question, and adventure attended with some danger on account of the snakes that infest this country (D’Ewes, 1857: 56-7).

In this entry D’Ewes is referring to Archibald Fisken, manager at Lal Lal for his uncle Peter Inglis, 1847-50; then licensee from 1850 onwards. The Lal Lal run, 18,313 acres, was first taken up by JW Stevens in 1845; Inglis took over the lease in October 1846.

Engineer Edward Snell visited Lal Lal Falls on 12 November 1855, and recorded the following account in his journal:

We had some luncheon at the Corduroy Bridge Hotel (the last 5 miles by the bye was over a plank road,) and then we struck off into the bush, steering North East for Lal Lal falls. We made the Lal Lal Creek 2 miles above the falls owing to our not getting the exact compass bearing and then tracked the Creek down until we came to the falls. I made a sketch of them from the top and afterwards descended into the ravine where we sat down, had dinner, grog, and a smoke and I sketched the view on the opposite page. We then visited the Little Falls on a creek about a mile further on and after a smoke and more grog started for Egerton … (Snell, 1988: 360).

Snell arrived in Australia in 1849, and it is not possible to determine how he knew of the falls, perhaps he was told about them at the Corduroy Bridge Hotel, at what is now Clarendon, or he knew of them through Parker’s or Braim’s publications, nevertheless his directions were somewhat vague and he and his party overshot them and had to travel down the creek to locate them.

Anthropologist, Aldo Massola (1968: 59), described the Kulin ‘myth’ of the ‘Lal-Lal Falls on the Moorabool River’ thus: ‘Bunjil made the falls to relieve the monotony of the landscape. He liked them so much that he decided to make them his earthly home’. This story is unsourced, however Massola (1968: x) explained in his foreword that the accounts he published ‘were collected over a period of ten years, from Aborigines in all parts of Victoria’, and he supplemented these with ‘the scant published material’. Other sites directly connected with Bunjil include ‘caves’ at Bushy Creek and Cape Schanck, and the rock-art site known as Bunjil’s Shelter in the Black Range near Stawell (Massola, 1957). Massola speculated that Bunjil chose to live at the falls because of its idiosyncratic features:

Apart from the fascination of watching the wide creek ending its placid run through the level plain by suddenly tumbling, with a mighty roar, down the 200 feet chasm, there were other reasons, no doubt, why Bunjil was made to live there. One was the fact that the swamp supported a large population of birds and other animals which assured the Aboriginals of plentiful supplies of food. Another was the comfort of the sand dunes on the south-east of the swamp, which make ideal camping places. A third, and no doubt very important reason, was the deposits of white pipe-clay on the east side of the swamp, which are now commercially quarried for paper clay (Massola, 1969: 70-71).

Charles Barrett (1944: 110) argued that Victoria is lacking in ‘majestic waterfalls’, though it does possess ‘some beautiful falls’, some of which have impressed international visitors.2 Yet Robinson, who visited the site in 1840 and 1846 considered the Lal Lal Falls were ‘magnificent’, and ‘the finest fall’ he had ‘seen in the country’. He also found the geology of the site ‘the best formation’ he had seen. Its significance lies in its cultural and natural values, yet apart from providing a name for the falls, Aboriginal cultural values were not instrumental in the sacralization of the site. Natural values provided the greatest interest in that process.

The aesthetic appreciation of waterfalls and the spectacles they offer is a landscape taste that has been documented to have existed in some cultures for over two thousand years (Hudson, 1998: 959). Hudson (1998: 959) has noted that waterfalls as recreation and tourism resources ‘have been largely neglected in scholarly literature’, which is surprising given that they have scarcity value. ‘Unlike fire, clouds and windtossed trees, however, waterfalls are not ubiquitous and, indeed, may be regarded as curiosities of nature along with caves, geysers, and glaciers’ (Hudson, 1998: 963).

2.2 Second Phase: Framing and Elevation 1865–1885

The second phase identified by MacCannell (1976) in the evolution of attractions is ‘framing and elevation’ which he argued results from an increase in visitation, when demand requires some form of management intervention, whereby the sight is displayed more prominently and framed off. In the case of Lal Lal Falls this phase began in 1865 and ended with the construction of the Lal Lal to Lal Lal Racecourse railway branch line in 1885. Reservation of the site in 1865 ensured that the falls would not be damaged by incompatible land use or allow them to encroach upon the nucleus and compromise the visual entrance to the falls.

The Lal Lal Falls formed part of Blakeney’s and Airey’s Lal Lal Pastoral Run which they first took up in early 1840. In 1843, Peter Inglis purchased the Lal Lal lease. From 1846, Archibald Fisken, Inglis’ nephew, was given the management of Lal Lal, and eventually took ownership in 1854. In 1857, freehold land became available as the government brought it up for auction. Section 8 of the surveyed section contained both the Moorabool and Lal Lal falls. The Star, a local Ballarat paper, in an editorial dated 19 September 1857 brought the sale to its readers’ attention, but the opening line reveals that local awareness of the falls was not widespread.

Probably few of our readers are aware that within ten or twelve miles of the township of Ballarat, there are two fine waterfalls, one of which from its picturesque beauty and its great height would not be unworthy of attention even in the best parts of the Scottish Highlands. These falls, the Lal Lal and the Moorabool, are situated in a beautifully undulating and finely timbered country on the south-eastern base of Warrenheep, from and around which mount, the streams which from them take their rise.

The editor did not begrudge Archibald Fisken receiving a fair compensation for the various improvements he had made to the section being sold. The Miner and Weekly Star (25/9/1857) made the following comment on the proposed sale of the Lal Lal Falls:

But, however, the question of how the area of the lot (537 acres) may be ultimately disposed, the Government should at once withdraw it from the present sale for the purpose of resurveying them, and of preserving to the public the beautiful waterfalls we have alluded to, as well as the extensive water frontages that by the present plan would in the event of a sale be for ever alienated.

The following week The Star (26/9/1857) increased the pressure on the Victorian Government to set aside the Lal Lal Falls when it published an account of a visit to the waterfall:

A traveller sends us the following description of these beautiful falls: On coming forward to a view of the Lal Lal Falls, which from the flatness of the country is done all at once, the eye suddenly beholds a cascade of water rushing over a precipice of rock 110 feet perpendicular height, into a ravine, lined on both sides near the top with basaltic columns, identical with what are to be seen at the Giant’s Causeway in Ireland, and at Staffa and Iona in Scotland; in every way shaped the same, being irregular polygons with from three to eight sides, set into each other with convex and concave joints and all standing perpendicular. From having seen these natural curiosities in the old country, which thousands visit annually from all parts of the world, it may be easily supposed that never having read of, or heard described the scenery of Lal Lal, that when I first saw these Pillars, I was struck with astonishment and wonder at the similarity; particularly when it is considered that the places are distant from each other 14,000 miles, I felt as if I had suddenly been brought in contact with old and familiar faces. But to return to your editorial remarks of 19th inst., I would beg leave to suggest, that when the Government do sell the adjacent lands, that they bind the purchasers to leave open roads through them to the Falls, so as the lovers of natural scenery may be able to ride, drive, or walk from Ballarat, Buninyong, Corduroy, and Mount Egerton (from which places the Falls are about equi-distant), without let or hindrance from the fortunate possessors of that part which surrounds decidedly the finest scenery and the greatest natural curiosities in this part of the Colony of Victoria.

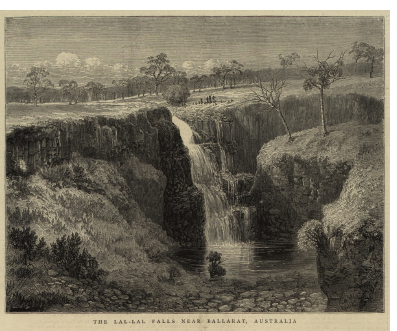

There is little doubt that the primary motivation in seeking the preservation of the Lal Lal Falls was its aesthetic value – the scenery of its landscape – and in this the moves to reserve them paralleled moves in North America to preserve wilderness in places such as Yosemite, Yellowstone, and Niagara Falls (Towner, 1996:160) (see Fig.2.2). The Australian News for Home Readers (25/7/1864) even went so far as to suggest the Lal Lal Falls were a miniature Niagara:

These falls, which are situated in a wooded country near Ballaarat, form the prettiest water scene the locality can boast. The watercourse is suddenly broken by a precipitate fall of the earth, almost as perpendicular as a wall. The water leaps down a great number of feet, forming a miniature representation of Niagara. The falls are a favourite resort for picnic parties, the surrounding country presenting many picturesque points, and they are usually visited by strangers among the other “lions” of the Ballaarat district.

The Government subsequently withdrew the Lal Lal Falls section from public sale, and 200 acres (90 hectare) were permanently reserved as the ‘Lal Lal Park’ in 1865.3 Norman (1984: 2) states the reserve was proclaimed in 1877 (Victorian Government Gazette, 1877: 1652). Its formal name is ‘Lal Lal Falls Scenic Reserve’. The purpose of scenic reserves is to preserve scenic features and lookouts of particular significance (LCC, 1980). From 1877 until 1964, the Scenic Reserve was under the control of a committee of management of four representatives from the Shire of Buninyong and the City of Ballaarat. From 1964, the Shire of Buninyong had sole management for the reserve (Victorian Government Gazette, 1964). From 1977, an officer with the West Moorabool Water Board was serving as unofficial caretaker of the reserve (Norman, 1984: 19).

An adjacent reserve known as the ‘Racecourse Reserve’, to the south of the Scenic Reserve, has been temporarily reserved as a possible car-park extension (Victorian Government Gazette, 1969: 1823). The Lal Lal railway station was constructed in 1862, and the Ballarat Star (26/4/1862) questioned its purpose, although it considered it ‘may prove however to be useful to picnic parties during the summer months’. Annual races were first held at the Lal Lal Racecourse Reserve in 1864.

2.3 Third Phase: Enshrinement 1885–1938

MacCannell (1976) has identified ‘enshrinement’ as the third phase in the evolution of attractions. Critical in the enshrinement phase of Lal Lal Falls is the Lal Lal picnic races. This phase began when access to the racecourse was improved in 1885, when a branch railway line was opened from the Lal Lal station that went directly to the racecourse. A spacious grandstand was erected in 1887, capable of accommodating 1,000 patrons (Griffiths, 1988: 112). The number of visitors to the Lal Lal races evidences the rapid tourism growth associated with this phase. In 1911, for example, special trains took 1,303 individuals to the Lal Lal picnic races (Bate, 1993: 152). Griffiths (1988: 112) described the New Year’s Day races at Lal Lal as an ‘institution’, with special trains catering for up to 30,000 visitors from Ballarat and district:

Many of the crowd came just for a picnic day, and remained in the outside reserve to enjoy themselves at the many side shows and boxing tent. Inside the course were office, kiosk, publicans’ booths, and plenty of bookmakers. The cover of the official programme warned punters to ‘Beware of Welchers, Bet Only with Recognised Bookmakers’.

According to Griffiths, the Lal Lal Turf Club held its principal meeting on New Year’s Day annually until 1936, after which it chose another day to avoid its clash with the Burrumbeet meeting. The last official meeting was 31 December 1938. Although several gymkhanas were held after 1938, the improvements were sold and the branch railway torn up and the racecourse reserve is now a paddock leased by the Shire Council.

2.4 Fourth Phase: Duplication

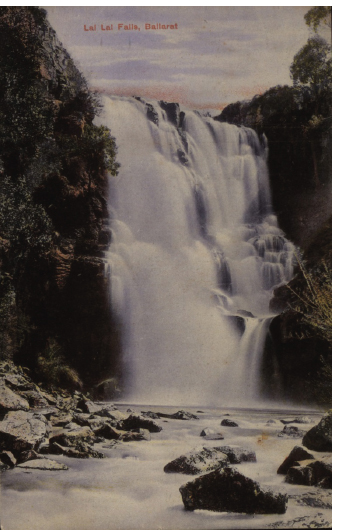

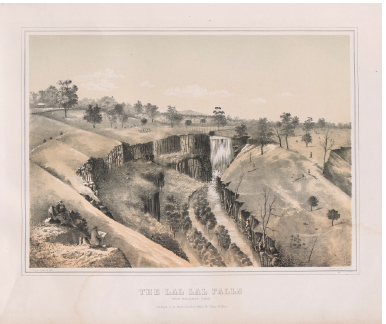

MacCannell’s (1976) fourth phase in the development of attractions is that of ‘duplication’, when copies of the nucleus of the attraction, in this case the waterfall, are made available through media such as paintings, photographs, and postcards (see Figs. 2.3 & 2.4).

The falls have been associated with prominent artists and photographers, including the German romantic colonial artist Eugen von Guerard who drew the falls in 1858, the Richard Ledger photograph taken some time after 1870, and the 1977 oil painting by Fred Williams.4 These are all examples of the influence of art on developing aesthetic tastes for landscape. Von Guerard’s drawing ‘Fall of the Lallal Creek’ is based on scenes he had sketched during 1853 and 1854 when he was gold mining in the Ballarat district (Tipping, 1982: 10). Tipping (1982: 10) claimed that von Guerard was attracted to places such as Lal Lal Falls because they ‘relieved the monotony of the basalt plains’ and ‘symbolised the violent and eroded forces of nature that had created them’.5

In the 1850s, the demand for black-and-white art was significant, and the Lal Lal Falls drawing is one of several landscapes that were reproduced by wood engraving. The Illustrated Melbourne News on 16 January 1858 reproduced the drawing from wood engraving. Von Guerard compiled a portfolio of sketches and newspaper cuttings, which included the Lal Lal Falls reproduction, and named it Australien Reminisunzen; it is now in the Mitchell Library in Sydney (Bruce, 1980). Von Guerard’s aesthetic sensibility with its romantic and picturesque taste for scenes based around mountains, gorges, forests, and waterfalls, calls to mind Rousseau’s declaration in his The Reveries of a Solitary of 1778, that ‘No flat country, however beautiful it may be, ever appeared so to me. I need torrents, rocks, firs, dark woods, mountains, rough tracks to climb up and down, precipices by my side to give me a nice fright’ (quoted by Towner, 1996:140).

In relation to waterfalls and advent of photography, Reilly and Carew (1983: 80) have noted that ‘Waterfalls were a common subject for photography in the nineteenth century and views of the Niagara Falls, especially, were in great demand throughout the world. In Australia from the 1860s onwards there was hardly an album or folio of photographs that did not include a view of a waterfall’. This is confirmed by the Fauchery-Daintree collection of 1858 that includes photographs of Turpin Falls and Glen Lyon Falls.6

2.5 Fifth Phase: Social Reproduction

For MacCannell, the final stage of sight sacralization is social reproduction which ‘occurs when groups, cities, and regions begin to name themselves after famous attractions’. In the case of Lal Lal Falls, social reproduction has occurred in the naming of the Lal Lal pastoral run now known as Lal Lal Estate, Lal Lal township, Lal Lal reservoir, Lal Lal railway station, Lal Lal primary school, and businesses such as Lal Lal Wind Farm, and Lal Lal Demolitions in nearby Ballarat. There are only two businesses that have reproduced the full name of the attraction – Lal Lal Falls Hotel, and Lal Lal Falls Cottage. In terms of the other Aboriginal names of the falls, Bunjil survives in the nearby Bungal Dam and the Bungall pastoral run on Lal Lal Creek adjoining Lal Lal first taken up in April 1838 by George Egerton.

2.6 Tourism at Lal Lal Falls

In 2001, Beggs-Sunter (2001: 3) summed up the history of tourism at Lal Lal Falls in the following terms: ‘One of the most significant heritage sites in our region is the Lal Lal Falls, once a favourite attraction, now virtually forgotten’. Thorpe and Akers (1995: 64-5) confirmed that, during the Christmas season, the Lal Lal Falls and Racecourse were popular family picnic areas. The Buninyong community subsequently planted conifers and constructed a rotunda along with barbecue facilities and toilet facilities. In 1969, Massola (1969: 71) described the falls thus:

With the passing of the Aborigines, Lal-lal Falls have become the top tourist attraction of the Shire of Buninyong, and have been developed accordingly. On the high ground adjoining the falls a picnic and caravan park has been laid out, and concrete steps, complete with safety railing, providing access down into the valley and to the base of the falls, have been built.

The reserve also has significant natural values, particularly the northern side of the Lal Lal Creek, approximately 500 metres downstream from the falls. In 1980, Lal Lal Falls were listed as one of several sites in the Ballarat region where sign-posted walking tracks were popular with day travellers and family groups (LCC, 1980: 148). The falls were also highlighted as a popular feature for recreational driving: ‘For many people, driving to an area is part of the recreational experience, while for others it simply provides access to areas where they will carry out some other activity. Pleasure drivers, the former category, look for diversity in scenery and natural history’ (LCC, 1980: 150). The Lal Lal Falls with their basalt columns are of interest to persons with some knowledge of geological phenomena associated with recent volcanic activity. Table 1.1 outlines the major management actions that have occurred along Lal Lal Creek and at Lal Lal Falls.

Tab. 1.1: Management actions at Lal Lal Falls and Lal Lal Creek

Year |

Management actions |

1863 |

Ballarat Water Committee dammed Lal Lal Creek, and Lal Lal Waterworks Association construct a 19km water race from Lal Lal Creek, just above the falls |

1864 |

Annual races held at the Lal Lal Racecourse Reserve |

1865 |

Government reserves 200 acres (90ha) as the ‘Lal Lal Park’ |

1873 |

Lal Lal Turf Club forms |

1885 |

Branch railway line opened from Lal Lal station to the Lal Lal Racecourse |

1887 |

Grandstand constructed capable of accommodating 1,000 patrons |

1938 |

Final Race meeting at the Lal Lal Racecourse |

1939 |

Construction of walking bridge on the pathway to the Lal Lal Falls |

1944 |

Lal Lal Turf Club disbands |

1951 |

Walking track to the falls constructed |

1953 |

Clearance of old trees in the picnic ground |

1957 |

Installation of playground equipment |

1961 |

Construction of lookout |

1963 |

Construction of cement stairway to the falls and safety rail above the falls |

1980 |

Reconstruction of the toilets, fireplaces, and seats and tables, and car park |

1988 |

Fencing constructed at the Reserve to protect rare population of Discaria pubescens |

1990 |

Access to the base of the falls is barred after a land slip kills two school children |

2004- |

Lal Lal Falls Advisory Committee undertook major upgrade of the site: removal of pine |

2008 |

trees, upgrading barbeque facilities, improving interpretive signage and marking new walking tracks |

2008 |

Walking track from Lal Lal Falls to Moorabool Falls opened |

In 1984, an environmental consultant, Norman (1984) suggested thirteen management recommendations, the most significant of which were:

Protection of the Australian anchor plant;

Prevention of abseiling from the walls of the ravine;

Closure of the pathway leading to the summit of the falls;

Repair or replacement of vandalised amenities;

Provision of firewood on a constant, year-round basis;

Removal of old and dangerous pines and their replacement with selected English trees;

Improvements to the pathway to the base of the falls, and the construction of an appropriate sign to direct visitors to the pathway;

Construction of a nature trail with plaques at select points that describe points of interest, from the picnic area to the base of the falls.

In 1988, a botanist from La Trobe University, in association with the Shire of Buninyong and the Department of Conservation, Forests and Lands, ensured that fencing was constructed at the reserve to protect a rare population of Discaria pubescens (Hairy Anchor Plant) under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act (1988). These plants were once common along the watercourses of the basalt plains. Since 1989, collection and seed propagation from the Lal Lal population has seen hundreds of plants introduced at fifteen localities in Western Victoria, including Mooramong Nature Reserve, Creswick Creek, and Carisbrook Reservoir.

Access to the base of the falls is via a concrete stairway and a walking track constructed in 1951. Norman (1984: 15) described it as a ‘roughly made dirt path’, that was ‘dangerous and not suitable to the whole spectrum of visitors. It is very uneven and covered in some areas by large obstacles in the form of tree roots, thereby restricting physically handicapped people and parents pushing prams’. There is a second path at the reserve, one that runs north from the picnic area to the summit of the falls (individuals near the summit can be seen in Fig.2.1). A fenced in car park was constructed in 1980 that allowed vehicular access to the picnic area. In 1980, the concrete seats and tables at the reserve were in a state of disrepair.

Public discussion of site management by the Shire of Buninyong took place in January 1984. Councillor D. Leather stated that ‘the Reserve was a popular site, but quite honestly, the place is a bit grotty’; Councillor A. Harbour argued that council ‘should scale down its activities at the Reserve because the only use it was getting was abusive’; Councillor Leather disagreed, stating that ‘many people used the Reserve and it required only little maintenance and, if kept on top of instead of neglected over years, then facilities would not be destroyed’ (Ballarat Courier, 21/1/1984). The Ballarat Region Conservation Strategy 1999-2004 acknowledged in its section on Koori Cultural History that ‘Lal Lal Falls was the special place of the great creator Bunjil (Bungal)’. The recommendations of the strategy were the provision of information to the general public by way of public lectures, school visits, and Koori heritage trail tours, and also to utilise the expertise of the Cultural Officer at the Ballarat and District Aboriginal Co-operative. In late 2001, the Moorabool Shire Council instituted a public meeting to discuss the future of the Lal Lal Public Reserve. Plans were announced to prepare a conservation management plan for the reserve. From 2004-2008, the Lal Lal Falls Reserve Advisory Committee, appointed by the Moorabool Shire Council, undertook a series of major projects at the reserve, including the removal of pine trees, upgrading visitor facilities such as barbeques and interpretive installations, and marking out new walking tracks. In early 2012, the Ballarat Courier undertook a survey of the Ballarat region’s favourite natural attraction. Lal Lal Falls was considered the region’s best, securing 37.5 per cent of the vote; Lake Wendouree came in second with 32.3 per cent, and Mt. Buninyong, third, with 9.4 per cent (Ballarat Courier, 8/2/2012).

2.7 Critical Moments in the History of the Lal Lal Falls

The falls and tourism there has been dramatically affected by three things: The diversion of water for gold mining in the 1860s; the cessation of the Lal Lal Races in 1938, and the death of two school children at the site in 1990.

In 1863, the Ballarat Water Committee dammed Lal Lal Creek so as to direct water across the Moorabool catchment for the use of gold miners in Ballarat. The Lal Lal Waterworks Association created other dams and these too affected the volume of water flow thus diminishing the spectacle of the Lal Lal Falls. This association constructed a 19-kilometre water race from Lal Lal Creek, just above the falls, to supply water to the miners at Dolly’s Creek, and later extended to the Morrison’s and Tea-Tree Diggings. The water from Lal Lal Creek was reported as having allowed Chinese diggers to ‘turn over with profit every portion of the ground about Dolly’s Creek containing the most minute particles of gold’ (Mining Surveyors’ Reports, October 1863). Although the literature fails to discuss the effect these diversions had on the flow of the water in Lal Lal Creek, the reduction in the volume of water that cascaded over the falls must, presumably, have been significant.

Another critical moment in its history as a tourist attraction came in 1990 when two school pupils died in a landslip whilst visiting the base of the falls. The Victorian State Coroner at the inquest found that there had been insufficient assessment of the region undertaken by the school’s staff in view of the potential danger of rockfalls. The Coroner found that the college concerned had ‘contributed to the deaths by undertaking a potentially dangerous activity without ensuring that appropriately qualified experts assessed the area before the crime’ (Abrams, 2002). Until the 1990 tragedy, it was possible to walk along a track to the base of the waterfall; however, access is now restricted and visitors are able to see the falls from a viewing platform. The barrier has not been particularly successful as the walking track is still prominent, which suggests visitors are ignoring the signs barring entry and walking to the base of the fall. Lal Lal Falls was also a site renowned for abseiling, but after the 1990 landslip, this activity was banned.

2.8 Conclusion

This historical analysis of the Lal Lal Falls, near Ballarat, in Western Victoria, traces its evolution from an Aboriginal cultural site into a recreational attraction. The Lal Lal Falls, situated within the traditional country of the Wathawurrung Aboriginal people, is one of Victoria’s most significant Aboriginal cultural sites, as it is one of several recorded living sites of Bunjil – the Kulin peoples’ creator spirit. The Lal Lal Falls became a tourist attraction more for its natural significance than its Indigenous cultural values. Its reservation as a public reserve in 1865 marked the emergence of the site as an attraction with a nucleus and an essential setting.

Tourism at Lal Lal Falls experienced its zenith when it was associated with the annual Lal Lal Races and, with their cessation in 1938, the Lal Lal Falls Scenic Reserve, in terms of visitor numbers, has experienced continued stagnation and general decline; though this has now been arrested by major intervention works in 2004-2008. Since 1938, there have periods of management activity when site works have been undertaken, particularly in 1963, 1980, and 2004-2008; however, the benefits of the first two actions appear to have been short-lived and the infrastructure associated with the ‘inviolate belt’ – visitor amenities such as toilets, fireplaces, seats and tables – were vandalised and allowed to fall into disrepair.

What is particularly poignant about the Lal Lal Falls is its sacredness in Indigenous value systems – one of a select number of living sites of the creator spirit, Bunjil, before departing into the sky. Its significance cannot be overstated. Yet, although the Aboriginal significance of the site has been understated in previous site promotion and off-site interpretation,7 visitor information and travel guides on the Internet are beginning to focus on the site’s Indigenous values. For example, Walkabout, has the following entry for Lal Lal Falls listed under ‘Things to see’ in the Buninyong district: ‘The local Kooris are said to have believed that Bunjil, their creator, resided at this place. The name is thought to be Aboriginal for ‘dashing of waters’.8

In many respects the landslip in 1990 and the two resultant fatalities and the subsequent management decision to attempt to restrict visits to the base of the falls represents the lowest point in the tourism history of the attraction.

Lal Lal Falls, as a tourism attraction – one with significant natural and cultural values – has undergone a fundamental transition from being ‘the top tourist attraction’ and ‘one of the most significant heritage sites’ in the Buninyong region, where thousands of people would congregate for picnic races, to an attraction ‘virtually forgotten’ in 2001, only to reemerge in 2012 to be the leading natural attraction in the Ballarat district. This study has gone some way to explaining this transition, by showing the value of the models provided by MacCannell, Butler, and Gunn, and demonstrating that, when combined, they possess considerable explanatory potential for understanding the evolution and history of a tourism attraction. Tourism at Lal Lal Falls experienced its zenith when it was associated with the annual Lal Lal Races and, with their cessation, the Falls, in terms of visitor numbers, has experienced continued stagnation and general decline until major site works in 2004-2008 which have seen the falls re-emerge in 2012 as the Ballarat region’s most favourite natural attraction.

References

Abrams, N. (2002). Principal and Teacher Duty of Care for Students. Student Wellbeing Conference 14 June 2002:1-45 [On-line:] www.emr.vic.edu.au/disabwel/PDFs/Norman%20Abrams%20 legal%20Liability%20Issues%20in%20 School.PDF] (accessed 4 November 2002)

The Australian News for Home Readers 25/2/1864

Ballarat, (1999), Ballarat Region Conservation Strategy 1999-2004: a strategy for Sustainable Living [On-line:] http://www.ballarat.vic.gov.au/8heritage2.html (accessed 4 November 2002)

Ballarat Courier 21/1/1984; 8/2/2012

Ballarat Star 26/4/1862, 4/1/1864

Barrett, C. (1944). Australian Caves, Cliffs, and Waterfalls. Melbourne: Georgian House.

Bate, W. (1993). Life After Gold Twentieth-Century Ballarat. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

Beggs-Sunter, A. (2001). Lal Lal Falls in Newsletter, Buninyong and District Historical Society Inc., October, p. 3

Billis, R.V. & Kenyon, A.S. (1974). Pastoral Pioneers of Port Phillip. Melbourne: Stockland Press.

Bonwick, J. (1863). The Wild White Man and the Blacks of Victoria. Melbourne: Fergusson & Moore.

Braim, T.H. (1846). A History of New South Wales from its Settlement to the Close of the Year 1844 (two volumes). London: Bentley.

Brown, P.L. (ed) (1935). The Narrative of George Russell of Golf Hill with Russellania and Selected Papers. London: Oxford University Press.

Bruce, C. (editor) (1980). Eugen von Guerard. Canberra: Australian Gallery Directors Council, Visual Arts Board of the Australia Council, Australian National Gallery, and Frank McDonald.

Butler, R.W. (1980). The Concept of a Tourist Area Cycle of Evolution: Implications for Management of Resources. Canadian Geographer, 24:5-12

Clacy, E. (1853). A Lady’s Visit to the Gold Diggings of Australia in 1852-53. London: Hurst & Blackett.

Clark, I.D. (1990). Aboriginal Languages and Clans – an historical atlas of western and central Victoria, 1800-1900. Clayton: Monash Publications in Geography, Monash University

Clark, I.D. (ed.) (2000a). The Journals of George Augustus Robinson, Chief Protector, Port Phillip Aboriginal Protectorate, Volume One: 1 January 1839-30 September 1840. Clarendon: Heritage Matters.

Clark, I.D. (ed.) (2000b). The Journals of George Augustus Robinson, Chief Protector, Port Phillip Aboriginal Protectorate, Volume Five: 25 October 1845-9 June 1849. Clarendon: Heritage Matters.

Clark, I.D., (2002). The ebb and flow of tourism at Lal Lal Falls, Victoria: a tourism history of a sacred Aboriginal site. Australian Aboriginal Studies, 2:45-53.

Clark, I.D. & Heydon, T.G. (2002). Database of Aboriginal Placenames of Victoria. Melbourne: Victorian Aboriginal Corporation for Languages.

D’Ewes, J. (1857). China, Australia, and the Pacific Islands … London: Richard Bentley.

Griffiths, P.M. (1988). Three Times Blest – A History of Buninyong and District 1837-1901. Buninyong: Buninyong and District Historical Society.

Gunn, C.A. (1994). Tourism Planning Basics, Concepts. Cases. Washington: Taylor and Francis.

Howitt, R. (1845). Impressions of Australia Felix … London: Longman, Brown, Green & Longmans.

Hudson, B.J. (1998). Waterfalls Resources for Tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 25: 958-973.

Land Conservation Council Victoria. (1980). Report on the Ballarat Area. Melbourne: Land Conservation Council Victoria.

Launceston Advertiser 14/2/1845.

MacCannell, D. (1976). The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class. New York: Schoken.

Macqueen, A. (2010). Frederick Robert D’Arcy: colonial surveyor, explorer and artist c. 1809-1875. Wentworth Falls, New South Wales: The Author.

Mansfield, P.G. (editor) (1982). Spielvogel Papers Volume 1. Ballarat: Ballarat Historical Society.

Massola, A. (1957). Bunjil’s Cave Found. The Victorian Naturalist, 74:19-22

Massola, A. (1968). Bunjil’s Cave – Myths, Legends and Superstitions of the Aborigines of South-East Australia. Melbourne: Lansdowne Press.

Massola, A. (1969). Journey to Aboriginal Victoria. Adelaide: Rigby.

Miner and Weekly Star 25/9/1857

Norman, C. (1984). Draft Management Plan for Lal Lal Falls Scenic Reserve. Ballarat: Department of Applied Biology and Environmental Sciences, Ballarat College of Advanced Education.

Osborn, B. (1973). The Bacchus Story – A History of Captain W. H. Bacchus, of Bacchus Marsh, and His Son. Bacchus Marsh: Bacchus Marsh and District Historical Society.

Parker, E.S. (1840) article in Port Phillip Gazette

Reilly, D. & Carew, J. (1983). Sun Pictures of Victoria The Fauchery-Daintree Collection, 1858. Melbourne: Library Council of Victoria, Currey O’Neil Ross Pty Ltd.

Smiles, S. (ed.) (1880). A Boy’s Voyage Round the World … London: John Murray [First published 1871].

Snell, E. (1988). The Life and Adventures of Edward Snell…. North Sydney: Angus & Robertson.

The Star 19/9/1857; 26/9/1857.

The Sydney Morning Herald 3/10/1846.

Thorpe, M.W. & Akers, M. (1995). An Illustrated History of Buninyong. Buninyong: Buninyong and District Historical Society.

Tipping, M. (ed.) (1982). An Artist on the Goldfields The Diary of Eugene von Guerard. Melbourne: Currey O’Neil.

Towner, J. (1996). An Historical Geography of Recreation and Tourism in the Western World 1540-1940. Chichester: John Wiley.

Walkabout Australian Travel Guide [On-line:] http://www.walkabout.com.au/locations/VICBuninyong.shtml (accessed 8 December 2002)

Withers, W.B. (1999). History of Ballarat and Some Ballarat Reminiscences. Ballarat: Ballarat Heritage Services [First published 1870].

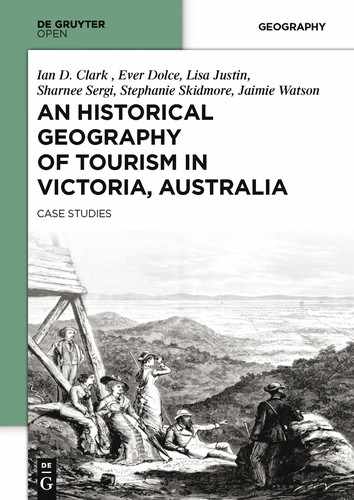

Fig. 2.1: ‘The Lal-Lal Falls Near Ballarat, Australia’. Source: The Graphic, 12 April 1873: p. 348.

Fig. 2.2: The Lal Lal Falls near Ballarat (1863); F. Cogne tinted lithograph. State Library of Victoria Pictures Collection H97.89/9

Fig. 2.3: Lal Lal Falls postcard (Ian Clark personal collection)

Fig. 2.4: Lal Lal Falls postcard (Ian Clark personal collection)

1 Osborn (1973:48) suggested the name of this waterfall was Peerewur, which meant ‘waterfall’ and ‘possums’. An earlier name for the falls is ‘The Mustangs’, in reference to where the Peerewur station’s mustangs were kept. The Peerewur Falls have a 3.6m fall, whereas the drop of the Lal Lal Falls is 34.16m.

2 Rudyard Kipling, for example, was impressed with Erskine Falls and wrote a poem about Lorne.

3 Norman (1984: 2) states the reserve was proclaimed in 1877 (Victorian Government Gazette, 1877: 1652).

4 Other photographs may be found in the National Library of Australia – see www.nla.gov.au.

5 Other waterfalls sketched and painted by von Guerard include Strath Creek Falls, The Weatherboard Falls, Clyde Fall, Moorabool Falls, and Wannon Falls.

6 This collection is in the State Library of Victoria

7 Sources that discuss the site’s indigenous values, such as Parker (1840), Robinson (1845 in Clark, 2000a), Braim (1846), Bonwick (1863), and Massola (1969), are not the kinds of publications that ordinarily inform populist tourism publications.

8 see Walkabout Australian Travel Guide [On-line:] http://www.walkabout.com.au/locations/VICBuninyong.shtml (accessed 4 December 2002)