3 The Buchan Caves Reserve by Ian D. Clark

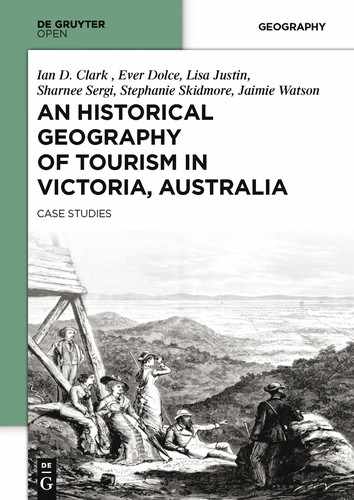

The Buchan Caves Reserve is some 360km east of Melbourne, near the township of Buchan. The Reserve is jointly managed by Parks Victoria and the Gunaikurnai Land and Water Aboriginal Corporation. It contains a visitor centre and facilities for overnight camping and day visitors. Within the reserve lies a honeycomb of caves with limestone formations – but there are only two show caves, Royal Cave (see Fig.3.1) and Fairy Cave (see Fig.3.2), and guided tours are conducted year round. The Buchan Caves Reserve falls within the Krauatungalung language area (Clark, 1998a: 189-190). This language or dialect, is one of five normally referred to as the ‘Ganai nation’ or ‘Kurnai nation’, a cluster of dialects sharing linguistic, social, cultural, political, and family associations.

3.1 First Phase: Sight Sacralization and Naming 1838–1907

In terms of MacCannell’s (1976) first phase in the development of attractions as ‘sight sacralization’ or ‘naming’, the name Buchan Caves is derived from the place name Buchan which is found in the pastoral run name, the creek name, and the township name. The show caves within the Buchan Caves Reserve complex have their own names, which will be discussed in the next section. Within the ethno-historical records and general literature on Buchan, several meanings and derivations are given for the name ‘Buchan’. George Augustus Robinson, the Chief Protector for Aborigines, for example, spelt Buchan several ways: Buckun (Jnl 3/6/1844 in Clark, 1998b); Buckin (Jnl 17/6/1844 in Clark, 1998b); Bucking (Jnl 21/6/1844 in Clark, 1998b); Buckan (Jnl 4/7/1844 in Clark, 1998b); and Bucken (Jnl 5/7/1844 in Clark, 1998b). There are several explanations of the derivation of Buchan, one that it is of Aboriginal origin, and another that it is Scottish. It is possible that it is polysemous, that is, that both have relevance.

One view is that it is of Scottish, or pseudo-Scottish, origin in light of the many people of Scottish origin who settled in the district and conferred the spelling Buchan after the town in Scotland (Howitt, 1904: 80; Seddon, 1994:63; Morgan, 1997: 21; Buchan Sesquicentenary Committee (BSC), 1989: 8). Another is that it derives from the Aboriginal word ‘bukin’ or ‘bugin’, a medicine-man of supernatural ability, dreaded because he stole human kidney fat its magical properties’ (Roberts, 1977: 14); and that the caves were the haunt of the Bukin (BSC, 1989: 8). However, according to Howitt, the Baukan was an evil spirit of which little could be learned. He was only able to state they were negative, but not very powerful, and consequently not much feared (Fison & Howitt, 1880: 254). A third is that Buchan is a contraction of the Aboriginal placename Bukkan-munji (Howitt, 1904: 80); Bukan Munjie (Fison & Howitt, 1880: 192; Salierno, 1987:51), Bukkanmungie (Gardner, 1992: 17), Buk Kan Munjie, Bukinmunjie (Seddon, 1994:62). Howitt (1904: 80) noted that Bukkan-munji was ‘the native name for the bag in which the Kurnai carries various articles’, and literally means ‘bag there’ or ‘the place of the bag’. According to Seddon (1994: 62) the name signifies a carrying bag, the common suffix ‘munjie’ indicating ‘women’s article’. Gardner (1992: 17) translates Bukkanmungie as ‘place of the woman’s bag’. The BSC (1989: 8), however, translate mungie as ‘water’. Another translation is ‘Grass bag’ (BSC, 1989: 8).

William Thomas informed the Central Board for the Protection of Aborigines, in 1861, that ‘Buccan’ meant ‘stack of rocks with a hole in it’ (Pepper & De Araugo, 1985: 120). The Ganai word for ‘cave’ was most likely to be the equivalent of their word for hole, ‘Ngrung’ (Fison & Howitt, 1880: 191), which is used in reference to the ‘hole of Nargun’ (see chapter on Den of Nargun).

3.1.1 Indigenous Values at Buchan Caves

In 1952, Robert H. Lavelle, a writer born at Bairnsdale, submitted a draft manuscript entitled ‘Buchan Caves Victoria Australia: Australia’s most wonderful Caves’ to the Department of Crown Lands and Survey.9 The manuscript is of interest because it contains an interpretation of the significance of the caves, as well as a description of the site by an Aboriginal man named Harry Belmont.

The Aboriginal tribes who inhabited these domains know of the caves from time immemorial, and for the reason that parts were used by the Headmen as a secret ritual ground, their existence was closely kept secret, and only by the chance of an inquisitive boy were they discovered in 1891 (Lavelle, 1952: 1).

Regarding the scenic setting of the caves, Lavelle (1952: 4) noted:

The whole is a dream of Paradise, without saints; that is unless you are willing to admit that the natural fauna are the spirits of the Saints, as the aboriginals do. … The best description I ever heard was uttered to me by an aboriginal friend, ‘Harry Belmont’, who pointed to the caves and said in his own tongue; ‘Bogong, Murryang, Biamee’. I asked him for the translation of those three phonetic words. It is: Bogong: the birthplace of a great spirit. Murryang: we meet in that dream land at the end of the ocean where Biamee lives. Biamee: God, or Great Spirit. This, truly is the finest description one can give of the Buchan Caves: ‘Paradise on earth’.

It has not been possible to learn anything about Harry Belmont. Preliminary analysis of the three Aboriginal words listed by Lavelle, as derived from Belmont, suggests a connection with New South Wales. Biamee is a reference to ‘baayama’ meaning ‘god’, listed in Austin’s (1992: 53) dictionary of the Gamilaraay language of northern New South Wales spoken at places such as Moree, Narrabri, Gunnedah, Tamworth, and Boggabilla. Ridley (in Smyth 1878, Vol. 2: 285) confirms that Baiame (pronounced by-a-me) was used by Aboriginal groups scattered across northwest and west New South Wales, and was used by the Wiradjuri people at Mudgee and other localities. ‘Bogong’ is a Ngarigu word for the brown moth Agrotis infusa which breeds on plains in southern Australia (Dixon, Ransom & Thomas, 1992). Adult moths migrate to mountains where they collect in rock crevices in early summer and were harvested by Aboriginal people and were a staple food source at this time. This understanding of bogong diverges from that given by Belmont. It has not been possible to find any reference to Murryang.

When the Bataluk Cultural Trail was being developed in Gippsland in the mid-1990s (see below), the trail brochure stated the following about the Aboriginal heritage of the Caves:

Traditionally Koorie people did not venture deep into the limestone caves at Buchan. There were, however, many stories about the wicked and mischievous Nyols which live in the caves below the earth.

Phillip Pepper, an Aboriginal elder at Lake Tyers, confirmed an Aboriginal involvement with the ‘discovery’ of one of the Buchan Caves. He recalled that in the early 1900s, his father, Percy Pepper was a friend of Frank Moon. They shared a passion for foot running, and would often run together. They also went rabbiting together. Phillip recalled that his father was setting rabbit traps with Frank Moon on one occasion when Moon ‘found one of the caves at Buchan’ (Pepper & De Araugo, 1989: 53).

In Gippsland, caves are associated with two mythical beings; the Nargun and the Nyol. For more information on the Nargun see the chapter on the Den of Nargun. Massola (1968: 74-5) has recounted the story of a Nyol at Murrindal.

Once, when the tribe was camped at Murrindal, one of the men went possum hunting. Possums were plentiful on the trees growing amongst the rocks there. While he was hunting, he noticed an opening between two rocks. He put his foot in it and was drawn in. He found himself in one of the many caves in the vicinity. The cave was lit by a strange light, and was inhabited by many very small people who came to him showing signs of friendship. They called him Jambi, which is a general term for friendship, although it means brother-in-law. He tried to get back above the surface, but found that he had to wrestle with the little people. They were very strong, although small, and although he fought many of them, they all overcame him. Feeling exhausted he lay down to rest. The little people, the Nyols, gave him rugs to sleep on and grubs to eat. The latter were a great delicacy, and he enjoyed them very much. At last, many of the Nyols went away and he was left in the charge of one of them. Everything had been quiet, but now he heard a rustling sound. One of the Nyols came to him saying he would show him the way to the surface of the ground. Before very long he was amongst his own people, but for several days could not tell them what had happened to him. His mind had temporarily gone blank.

3.1.2 The Buchan District: a Brief History

In early 1838 Edward Bayliss travelled from Aston, Maneroo, in search of grazing country, through Suggan Buggan to Buchan where he camped on the river flat, marked out a temporary station, and determined he would return with cattle. Returning to Maneroo, his reports on the Buchan district were so positive, that John Wilkinson started immediately and took possession of Buchan. When Bayliss returned later in 1838, he found Wilkinson established in the Buchan district and he was forced to go upstream up the Buchan River valley where he established the Gelantipy run in 1839. Wilkinson and Bayliss only stayed two seasons in the Buchan and Gelantipy districts, moving to the south in search of new pastures. By 1842, Fraser Mowatt had acquired the Buchan run (BSC, 1989: 6). Archibald Macleod, and his sons Norman and John, took possession of the Buchan run in 1845, and remained in control until 1862. Leases for Buchan were transferred frequently (see Billis & Kenyon, 1974), until the run was forfeited in 1880.

The Buchan area homestead was surveyed in 1866 and amended the following year by contract surveyor Arthur F Walker. G.H. Wilmot, district surveyor, undertook a comprehensive survey of 8,000 acres in the parish of Buchan in 1868, however demand for land was limited, and the major part of the area was selected, and resurveyed at a later date. Buchan was proclaimed a town in May 1873, and the town boundaries surveyed in 1874.

The presence of large caverns at Buchan was first mentioned in Stuart Ryrie’s 1840 report (Ryrie, 1840). The Argus (17/11/1854) published a report from a staff member of the office of the Surveyor-General employed on the Omeo goldfields, in which it is announced that gold had been found in the Buchan district. The report mentions that the caves in the Buchan district were not extensively known:

We traversed a portion of the country on the Buchan River. … Some of the caves, I am told, are very beautiful, but have not been as yet explored to any extent. In passing over parts covered with the most luxuriant grass, openings are to be observed, down which if a stone is rolled its re-echos can be heard for hundreds of feet. We visited some of the caves, but were unable to bring anything away, excepting a few small stalactites, &c., as we had no means of carrying them.

An early account of a visit to the Buchan caves was published in the Gippsland Times of 27 March 1873. The party stayed at the Buchan pastoral station where they received hospitality from the station manager as the nearest accommodation house was eight miles distant. The account provides details of the earliest known photography in the Buchan Caves.

A start was then made for the Murrindal mine and Buchan caves. Mr Cornell accompanied us with his photographic apparatus, for the purpose of taking a view of the interior of the largest cave.10 ... It is almost impossible to describe this wonderful place, it requires to be seen, and is well worthy of a trip from Melbourne. ... Mr Cornell succeeded in obtaining a photo of the pulpit rock, but not a good one, there is no doubt with proper appliances the whole interior could be taken (Gippsland Times, 27/3/1873).

In July 1873, Mr G.F. Ulrich, a geologist, in the company of a director of the Back Creek Silver and Lead Mine, visited Buchan, accompanied by a correspondent from Bairnsdale. This party also stayed at Buchan station (Gippsland Times, 5/7/1873). In April 1878 members of the government’s Wattle Bark Commission, availed themselves of the opportunity of visiting the caves at Buchan (Gippsland Times, 15/4/1878).

On 28 August 1880, the Australasian Sketcher with Pen and Pencil published an article on the Buchan caves:

DISTRICT SCENERY. THE BUCHAN CAVES. (BY E.M. Buchan.)

The hills here are pierced with scores–nay probably hundreds, of caves. With the exception, however, of those contiguous to the township, but little is known of them. The cathedral cave is, not only one of the most interesting but the one best known, and I set forth to explore it. ... A lady friend, who visited this cave, informed me that one of her party was induced to sing here, and the effect of the harmony rolling along the vaulted roof and reverberating throughout the distant, and lofty intricacies of the cavern, was magnificent. A scientific friend also informs me, that entombed beneath the stalagmite, which forms the floor of the cave, the fossil bones of gigantic marsupials are sometimes to be found. ... I found the light from my lantern insufficient to enable me to see the roof of some of the chambers, and would suggest that visitors to these caves should provide themselves with magnesium wire. … As it is, I think Buchan is destined to become a picturesque little hamlet well worth the tourist’s visit, if he be anything of a mountaineer.

In 1885 a hotel named the Cricket Club Hotel was established in Buchan by Henry Schacht. In the Gippsland Times of 29 May 1885, Shacht informed its readers that ‘tourists, travellers, and others will find his establishment replete with every convenience. The celebrated Buchan caves, which are well worthy of a visit, are within a short distance of the township, and visitors can always obtain a guide at the hotel. Saddle horses can be obtained on hire, and good accommodation paddocks are provided. Newport’s coach from Bruthen also arrives and takes its departure from the hotel’ (Gippsland Times, 29 May 1885). From that issue onwards, Schacht regularly promoted his services announcing in advertisements that ‘Tourists and others desirous of visiting the Buchan Caves can be furnished with guides’.

Julian Thomas, aka ‘The Vagabond’, visited the Buchan district in May 1886 and reported on his experiences. At Bruthen he met Frank Welby, the owner of Buchan station, who served as his guide. Thomas is one of the first to mention the destruction of some of the stalagmites and stalactites by those who visited the caves.

The far-famed Buchan caves are largely composed of limestone, and consist of underground caverns, the extent and number of which is unknown. ... Provided with candles and kerosene torches, one follows the guide, who brings the visitor to “the pulpit, and chair, and canopy,” formed of pure limestone, which sparkles beneath the light, casting weird shadows around. … The Spring Creek caves and the Murindal caves are said to be equal to Wilson’s caves. In some places these are highly dangerous, and one should not enter without a guide. Unfortunately, too, in all the caverns sacrilegious hands have broken off some of the finest stalactites and stalagmites (The Argus, 22/5/1886).

In 1889 the first geological survey of the Buchan Caves was commenced. James Stirling, Assistant Government Geologist with the Mines Department, published a description of Duke, O’Rourke, and Dickson (Dixon) caves, and the Spring Creek, Wilson Creek, and Murrindal caves. He recommended that the Buchan Caves be developed as a tourist attraction, along the lines of the Jenolan Caves in New South Wales. Stirling made ground plans of the Buchan and neighbouring caves and heliotype plates from the expedition photographs by J.H. Harvey, illustrating views in Wilson and Dickson caves. These photographs (and others by Harvey not published in the report) have long been seen as being the first photographs taken in caves in Victoria (Douglas, n.d); however it is clear that Douglas was unaware of the Cornell photographs taken in 1873.

In February 1889, Stirling delivered a lecture entitled ‘The Caves of Australia’ to the Sale Branch of the Australian Natives Association. The Gippsland Times (25/2/1889) published an account of his lecture:

The Buchan caves were of great interest to Victoria at the present time. Although known for many years, no systematic attempt was made to explore them until recently when his assistants, Miners Ralston and Tetu, accompanied by Mr Rellie, of Buchan, began to make a survey of the chambers, under his instructions. Having visited the caves, and examined the newly discovered chamber, he could with safety say that they were certainly the best caves yet discovered in Victoria. Although, so far as is known at present, they were not as large as the Jenolan caves, yet in many respects they were quite equal to these now celebrated caverns in point of beauty and interest. … After tracing some of the steps in the course of time revealed by the caves, the lecturer concluded by expressing a hope that some of his fellow Australian Natives would be roused to the importance of investigating the underground wonderland of Australia, and, by searching, discover many relies of bygones ages in this great country which supplied so many natural history curiosities to the world’s museums. … At short intervals Mr Harvey, secretary to the Photographic Association, Melbourne, who is accompanying Mr Stirling, exhibited views by the aid of a magic lantern, illustrative of the lecture.

On 1 May 1889, the Bendigo Advertiser reported that acting on Stirling’s recommendation, ‘the Minister of Mines has recommended the Lands department to permanently reserve the celebrated Buchan caves which Mr. Sterling [sic] so graphically describes’. The Bairnsdale Advertiser and Tambo and Omeo Chronicle (2/5/1889) explained that Stirling had recommended their permanent reservation ‘otherwise many of the striking physical and natural characteristics of the colony may otherwise lose their freshness and scientific value’. The Gippsland Times (12/3/1890) quoted from Stirling’s report:

The widespread interest which the Buchan caves undoubtedly obtain, … should, I think, suggest the advisability of having a proper supervision and further scientific examination made. I would recommend that, in addition to the reservations which have now been made at Spring Creek, Wilson’s Cave, and Dixon’s cave, some competent person should be appointed as care-taker, whose duties it would be to complete the exploration for new chambers, construct ladders and hand rails in different parts of the caves, and systematically carry on the work of removing portions of the stalagmital floors in search of fossils. The specimens already obtained in the breccia and cave earth being deemed of sufficient importance to warrant further scientific explorations, should it be desired to light up the caves by electricity, especially the Royal chamber in Wilson’s Cave, there should be no difficulty, as water power to drive a dynamo is readily obtainable from the Buchan River close by.

In 1897, the Bairnsdale Advertiser and Tambo and Omeo Chronicle reported on the state of research at the Buchan Caves:

The great caves at Buchan, and the scenery in their neighborhood–the Devil’s Glen, the Snowy River’s junction with the Buchan, and the Pyramids, for example are well worthy alike the attention of the geologist and the tourist, the scientist and the mere lover of the beautiful in nature. … Considered geologically the formation of rocks in the Buchan valley belong to the middle Devonian period. The caves are full of stalactites and stalagmites, the largest chamber being about 100 feet long by 35 feet wide, and 35 feet high. As yet no successful search has been made for fossil remains of the gigantic kangaroo, or mammoth wombat, so there is a great field yet untouched for subterranean exploration. The three principal caves at Buchan are Wilson’s cave, distant about 4 miles from the Buchan post office; the Spring Creek cave, about one mile; and the Basin Creek cave, about 14 miles to the north east. There are number of other caves in the district, but not containing many stalactites. It is generally believed by residents of the district that there are other caves yet to be discovered, but it is very difficult to find the mouth or entrance to a new cave, as it is usually on the side or at the foot of a hill, and covered with grass and ferns. … None of the principal caves have been thoroughly explored, and it is reasonable to suppose that there are other chambers yet undiscovered, awaiting in their awful darkness for someone to enter them and behold their beauty (Bairnsdale Advertiser and Tambo and Omeo Chronicle, 10/8/1897).

A.E. Kitson, a geologist with the Mines Department, in 1900 reported on the caves along Spring Creek. He recommended that cave reservations be set apart along Spring and Cave (now Fairy) creeks, at Dickson, Slocombe, and Wilson caves, in the vicinity of The Pyramids and at the Camping Reserve south of the Dickson Cave area. By 1900 many of the more accessible portions of the caves had been damaged by vandalism, but Kitson recommended that outstanding features should be preserved and suggested new passages and chambers would likely be found along unexplored portions of the cave complex. As a result of Kitson’s report 65 ha, being the unsold portion of the Buchan township, were set aside as a caves reserve by the Department of Crown Lands and Survey (Government Gazette, 19/7/1901; Swift, 1951: 3), and 48 ha adjoining this in the vicinity of the Spring Creek caves were also reserved (Government Gazette, 29/1/1902).

In January 1902, the Bairnsdale District Commercial and Progress Association discussed the Buchan Caves during one of their monthly meetings. Members expressed concern that the Government was not taking any care of the caves, and there were calls for their protection. The installation of electricity was recommended as well as the development of the caves for tourism (Bairnsdale Advertiser and Tambo and Omeo Chronicle, 18/1/1902).

In April 1902, ‘Vigilance’, a concerned citizen from Bairnsdale, wrote to The Argus (10/4/1902) about the protection and preservation of the Buchan Caves:

The Spring Creek caves, being most accessible, have already suffered severely from the wanton acts of vandalism perpetrated from time to time by various visitors some of what were doubtless the most beautiful of the chambers therein having been ruthlessly destroyed and hundreds of stalactites broken off and removed. In consequence of the want of supervision these wonderful phenomena which were the result of Nature’s operations through countless ages, and which should have been the delight of generations to come, have been shorn of much of their attraction, and no punishment could be too severe for those who have so shamefully demolished them. In like manner the other caves in the district of Buchan are being ruined, and unless measures are at once taken to protect them their beauty will be gone, and what should be the means of attracting increasing numbers of tourists from this and other states to what is one of the most healthy localities in Victoria will entirely lose their charms. With the example of New South Wales before us it is surely not too much to ask that caretakers be appointed for the various caves and better facilities for reaching and exploring them be given, such as tracks to the month of the caves and ladders to descend to the various chambers. Were such methods of popularising them adopted there would, I am sure, set in to these beautiful spots a regular stream of visitors equal in magnitude to that which now wends its way to the Jenolan and other caves in the neighbouring state. They only require to be known more widely to be more fully appreciated.

In April 1902, the Bairnsdale Advertiser and Tambo and Omeo Chronicle published a series of articles on Buchan and its Caves by ‘Mascotte’.

The caves have been almost completely stripped–denuded of almost the last stalactite. And you are told, and can easily believe–that the others will soon be in a like deplorable condition unless a somnolent, listless Government wakes up once in a while and hires a man to watch these caves with a good deal of carefulness and a gun, but that is quite unlikely. ... But all the caves are not destroyed, by any means (Bairnsdale Advertiser and Tambo and Omeo Chronicle, 15/4/1902).

Mascotte’s second article concerned the Spring Creek caves (Bairnsdale Advertiser and Tambo and Omeo Chronicle, 19/4/1902). The third article was about the Basin caves. The third article is of interest as it shows the actions of a local resident who took it upon himself to provide a level of protection to the caves near his residence.

The Basin caves are some distance from the township–about 12 miles, in fact–and the road thither is mostly uphill, and tedious. Up till quite recently these caves were much the best preserved of all, principally due, no doubt to their distance from the town and the difficulty of access. Lately, however, wholesale depredations have been made upon their contents by systematic robbers who, despising such commonplace means of despoilation as are practised by everyday vandals actually went to the caves equipped with a horse and cart, and wrecked a great proportion of them to fill the vehicle. A neighbouring resident Mr Slocombe, has wasted a considerable amount of his own time in writing to the Government with respect to the ruthless destruction that has been going on and asking that some steps ought be taken to put a stop to it. But this being a purely national matter and not one of merely political expediency or personal profit, no notice has been taken of either the representations or the request, except that a few notices, warning visitors not to interfere with the caves, have been posted up. Ultimately Mr Slocombe took matters into his own hands and fastened up the entrances to several of the best caves, and now entrance to these cannot be obtained without his consent–which is a very good thing. But the preservation of these caves is not a matter for unremunerated private action. It is the unmistakable duty of the Government to preserve such remarkable curiosities as they represent, at whatever cost (Bairnsdale Advertiser and Tambo and Omeo Chronicle, 29/4/1902).

The Bairnsdale Advertiser and Tambo and Omeo Chronicle (26/8/1905) continued to maintain the pressure for government action in an editorial published in August 1905:

Successive Government geologists have urged that some proper steps should be taken to “develop” by exploration the beautiful limestone caves at Buchan. The present occupant of the position Mr Dunn, has furnished the Government with a lengthy report on the caves, and a recommendation that cash rewards should be offered for the discovery of new caves. He also recommends that all possible precautions should be taken to protect the caves from vandalism. ... There are very few people living in the vicinity of the caves, and visitors are exceedingly infrequent. ... Mr Dunn considers it as exceedingly probable that a big national asset is going to waste at Buchan, and he fully believe that proper exploration work will lead to very important discoveries. ... If it was the particular business of any individuals to attract visitors to Buchan the trip there would become one of the most popular on the continent, for it would possess attractions that are not to be found anywhere else. But at present it is no-one’s business. The caves are to a great extent neglected because almost wholly unknown outside the district. But for the zealous and unremunerated care of the cave man who takes any real interest in them and who for years officiated as their caretaker, the caves would long ago have ceased to be in any way attractive. Mr Dunn’s suggestion for the offering of cash rewards for the discovery of new caves is a good one, no doubt, but its ultimate value must depend upon whether or not the Government take steps to have all the caves that have been or may yet be discovered “reserved” and properly cared for. Someone must be appointed to look after them and must be paid for doing it, of course. Everything in connection with the development and protection of the caves must be done by the Government, because there is no public body or community of people to whom the responsibility could be delegated. The municipality of Tambo, in the territory of which the limestone deposits are situated, is not interested in caves, and any attempt to get it interested to a sufficient extent to undertake the work of protecting the known caverns and prospecting for more would he hopeless at the outset. The question is one wholly for the Government and properly so, seeing that the whole matter is a national one. It is very much to be hoped, from every point of view, that the recommendations that the geological director has made to the Government in connection with the caves at Buchan will be acted upon and amplified (Bairnsdale Advertiser and Tambo and Omeo Chronicle, 26/8/1905).

3.2 Second Phase: Framing and Elevation 1907–Present

The second phase identified by MacCannell (1976) in the evolution of attractions is ‘framing and elevation’ which he argued results from an increase in visitation, when demand requires some form of management intervention, whereby the sight is displayed more prominently and framed off.

One local resident who responded to the challenge to explore the Buchan cave complex was a young athlete and local resident named Francis (Frank) Herbert Arthur Moon. The Argus (3/10/1906) reported on one of his discoveries:

BUCHAN, Tuesday–The new cave discovered by Frank Moon, a young athlete, is situated on the south side of Spring Creek, half a mile from the Buchan Post-office. Moon noticed a fissure in the rock, and determined to investigate. With three comrades, he entered a narrow fissure, measuring 6ft. by 2 ft. with acetlyne [sic] lamps. … The cave is absolutely perfect, and out-rivals all others in the district in extent and rugged beauty. It can be easily drained (The Argus, 3/10/1906).

As a consequence of Moon’s discovery, the Victorian Premier, Thomas Bent, despatched A.E. Kitson, an officer of the geological branch of the Mines department to investigate and report. According to The Argus (11/10/1906), ‘Certainly the earlier discovered caves at Buchan have suffered severely during the past 10 years from wonton acts of vandalism, but there are still left immense subterranean areas, which should prove invaluable as attractions for tourists. The unaccessability [sic] of Buchan has been the only factor keeping these caves back for so many years. When once the township is reached the caves are close at hand. The most recently discovered is entered on a chamber only half a mile from Buchan Post-office. But Buchan itself is remote from any railway line, and at present is difficult of access. The work of providing means of reaching these caves will be given to the Tourist Bureau which it is proposed to establish’ (The Argus, 11/10/1906).

The Gippsland Times reported on the findings from Kitson’s investigation:

Mr. Kitson has paid several visits to these caves and he reports that there are several known groups, in addition to the one discovered a few days ago. They are as follows: Spring Creek Caves, Buchan; O’Rourke’s caves, Buchan; Green caves, Buchan; Slocombe’s caves, on Basin Creek, 12 miles north-east of Buchan; Murrindal caves, six miles north-east of Buchan. ... Mr Kitson reports that the caves have never been systematically explored, and he has no doubt whatever that careful examination and labor will reveal numerous additional chambers, adorned with stalactites, stalagmites and stalactical drapery. In several portions of the explored passages there are small openings which probably lead to larger passages and chambers. As a result of representations formerly made by Mr Kitson, 120 acres of the mining reserve and 160 acres of the township reserve at Bruthen have been reserved for the preservation of caves. Spring Creek runs into the “Bruthen River just outside the town, and a small tributary called Cave Creek runs into Spring Creek, the caves on these waterways being close to the town. The Spring Creek, Wilson’s, Dickson’s, Green and Basin Creek caves, says Mr Kitson, are particularly worthy of preservation, for though all but the last have suffered from the vandalism of sight-seers, who have destroyed most of the smaller stalagmites and stalactical drapery within reach, there still remains a wealth of natural beauty, besides which there is a great probability of the discovery of new caves and chambers. In advocating the preservation of these limestone caves, Mr. Kitson says that the limestone country generally in the Buchan district has a very pleasing aspect. ... With improved roads to Buchan, and the opening up of the caves, Mr Kitson is confident that Buchan will become a celebrated tourist resort (Gippsland Times, 15/10/1906).

As a consequence of this new discovery, the Minister of Lands instructed an officer of his department to ascertain how far the caves underlie Crown land. Once this information was obtained, it was the minister’s intention to authorise a local resident to act as caretaker for this portion of the caves (Portland Guardian, 22/10/1906).

The Argus continued to agitate for the immediate protection of the Buchan Caves. ‘Local residents are already exhibiting stalactites and stalagmites taken from the new cave, and, owing to the use of the “emergency torch,” a piece of bark saturated in kerosene, some beautiful formations have been destroyed’ (The Argus, 25/10/1906). Frank Moon was appointed caretaker and he threw himself into the task of exploring the Buchan Caves complex.

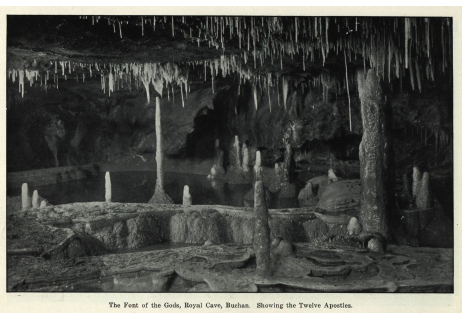

The ‘Fairy Cave’ was ‘discovered’ by Frank Moon, on 16 March 1907 (Bairnsdale Advertiser and Tambo and Omeo Chronicle, 19/3/1907). He saw a small hole or crevice in the side of a hill, and enlarged it with some gelignite, and descended fifty feet to what is now known as ‘Fairy Cave’ (Salierno, 1987: 55). Paths were constructed through the cave and wire netting installed to protect the decorations. Fairy Cave was opened to the public in December 1907. Initially, lighting was provided by candles given to the visitors and magnesium lamps used by the guides. Electricity was connected in 1920 when a generating plant was installed, and this was used until 1969 when State Electricity Commission power was connected. Subsequently there has been much upgrading of the Caves and associated infrastructure.

In April 1907, W. Thorn, of the Lands department, visited the Buchan Caves to report to the Minister on the recent discoveries and their comparison with the Jenolan Caves, in New South Wales, of which he recently made an inspection. He also reported on any works necessary for opening up the district to tourists and for the protection of the caves. It was hoped that the new caves will be opened up sufficiently to attract a considerable number of visitors next season (The Argus, 5/4/1907). The Bairnsdale Advertiser and Tambo and Omeo Chronicle reported that the Buchan caves were becoming better known. ‘Recent visitors who have returned to the metropolis speak in glowing terms of the wonderful sights they saw in their inspection of these new caves. This should have a good effect in hurrying on the department to open up the roads to Buchan and making the caves accessible to the public. It is unlikely, though, according to a statement made by the Minister of Lands to day, that much can be done in this direction at present. Mr Mackey has promised, however, to have the arrangements for rewiring the caves completed by next summer. The roadwork will probably be finished a little sooner’ (Bairnsdale Advertiser and Tambo and Omeo Chronicle, 4/4/1907).

The ‘Royal Cave’ was located in November 1910, by a party led by Frederick J Wilson, Caves Supervisor of the Buchan Reserve since 1907, and the discoverer of the Jenolan Caves in New South Wales (Swift, 1951: 6). The others were Frank Moon and Constable Brown, a local policeman (Allen correspondence 28/5/1968 in File ‘Caves and Tourism’). The Argus (9/11/1910), in reporting its discovery, noted that it ‘is said by experts to equal if not excel, anything at Jenolan’. At Royal Cave, in 1913, William Bonwick and William Foster, reserve employees, cut through a solid block of black marble, and used a large quantity of explosives to get through 150 feet. The cave opened to the public in November 1913.

The Argus in 1951 summarized some of those responsible for the framing and elevation of the Buchan Caves:

Associated with the opening and exploration of the caves was the late Dr. John Flynn, later famous as Flynn of the Inland. The Doctor was one of the first to enter the new chambers, and his photographs of them, made into lantern slides, were shown to big audiences. He convinced the Government of the day that the Buchan caves were a wonderful treasure. Parliament acted, and Frank Moon was asked to take charge of the caves and explore the unknown portions. His first important discovery came on March l8, 1907, when he entered the Fairy cave from a fissure on the hillside. From a side passage in its depths he discovered the Royal cave a year later, but falls of rock made the way unsafe, and a new entrance tunnel was driven through the hill. Before the visitors could come to marvel at this fascinating underworld there was hard work to be done. WITH the guidance of Mr. F. Wilson, the discoverer of Jenolan, the tunnels, passageways, and illuminations were planned and commenced. Others played their parts, too. The late William Bonwick and the late William Foster, before the days of the pneumatic drill, wielded hammer and chisel day after day, clearing passages through the solid rock. Cement for the later tunnels and stairways was carried in bucketful by bucketful by Frank Moon’s son-in-law, Frank Hansford. DAVID SWIFT (The Argus 16/11/1951).

In July 1918, a committee of Management was constituted which continued until its reconstitution as an advisory committee in 1946. In October 1918, The Argus reported that the Minister of Lands was concerned that the caves were now illuminated with magnesium ribbon which was rapidly destroying the finer features of the caves, and proposed to install electric lighting. ‘The cost of the magnesium ribbon light was £50 a year. Last year 3,465 tourists visited the caves and their admission money represented a revenue of £350. In addition revenue had been derived by the railways. For £670 the caves would be electrically lit and there would be no recurring expense as was the case now’ (The Argus, 11/10/1918).

In April 1925, The Northern Miner noted that ‘The thousands, of people who have already seen the Buchan Caves, and the tens of thousands who will see them in the future, will be thankful that this invaluable sight-seeing resort was saved to the State in the nick of time ... But for the strong and persistent recommendations of geologists, who were able to realise their worth, most of the area embracing the caverns would have passed from the Crown into private hands 25 years ago’ (The Northern Miner, 21/4/1925). Yet The Argus was critical that the Victorian Government was not doing enough to promote the Buchan Caves. It considered that ‘If they had been the property of private individuals instead of the State they would have been earning a fortune long ago’ (The Argus, 5/2/1926).

3.3 Third Phase: Enshrinement 1937–Present

MacCannell (1976) has identified ‘enshrinement’ as the third phase in the evolution of attractions when framing material that is used has itself entered the first stage of sacralization (marking). In the case of the Buchan Caves this would most likely refer to the facilities and other activities that are available to the visitor at the Caves, such as picnicking and camping, activities that don’t necessarily involve any interaction with the nucleus that is the caves themselves, other than having them provide the location or setting for the activity.

In 1937 The Argus reported that a development plan for the Buchan Caves was being prepared by the committee of management of the resort. ‘The proposals to be developed include the establishment of native game sanctuaries and a national park, the provision of camping facilities for at least 300 pic-nic parties, a swimming pool and the cutting of tracks through about 700 acres of bush. Mr Lind said last night that he hoped that the resort would become one of the most attractive in Vicoria. If the estimates of cost are approved the work will be undertaken soon by the Public Works Department’ (The Argus, 24/11/1937). The following year the Gippsland Times (19/5/1938) reported that the improvements being made at Buchan Caves National Park were coming from unemployment relief funds. The works included ‘a swimming pool fed by the underground river, camping and parking areas, children’s playground, and tennis courts. The reserve is to be made more attractive by extension of the tree-planting scheme, including an inner reserve in the lower part of the valley for native fauna, Proceeds from admission charges to the caves are paid into consolidated revenue. The chairman of the caves committee is the chief clerk of the Lands department’ (Gippsland Times, 19/5/1938).

The Buchan Caves National Park was formally dedicated on 3 December 1938 by the Minister for Forests (Mr. Lind). ‘Mr. Lind will also open officially the new automobile camping park in the Buchan Caves National Park at 3 p.m. The camping park is claimed to be the most modern in Australia. It has facilities for dances and concerts, a kitchen, and dining hall, showers, bathrooms, a swimming-pool sunk in marble rock, tennis-courts, children’s playground, fire-places, car-washes, and it is sewered. An all-weather road leads to it from the Prince’s Highway at Nowa Nowa’ (The Argus, 2/12/1938).

The Caves were closed in February 1942 because all the staff had enlisted for military service in WW2, and owing to the difficulty of maintaining transport facilities between Lakes Entrance. In April 1946, the Caves were re-opened when two members of the former staff were demobilised from the army, and after some reconditioning and overhauling of the electric light and pumping plant at the cave complex had been undertaken (Gippsland Times, 10/1/1946).

3.3.1 Management History of the Buchan Caves

AE Kitson, a geologist with the Mines Department, in 1900 reported on the caves along Spring Creek. He recommended that cave reservations be set apart along Spring and Cave (now Fairy) creeks, at Dickson, Slocombe, and Wilson caves, in the vicinity of The Pyramids and at the Camping Reserve south of the Dickson Cave area.

By 1900 many of the more accessible portions of the caves had been damaged by vandalism, but Kitson recommended that outstanding features should be preserved and suggested new passages and chambers would likely be found along unexplored portions of the cave complex. As a result of Kitson’s report 65 ha, being the unsold portion of Buchan township, were set aside as a caves reserve by the Department of Crown Lands and Survey (Swift, 1951: 3), and 48 ha adjoining this in the vicinity of the Spring Creek caves were also reserved. Yet, the Caves were not formally opened to the public until 2 December 1907. Initially, lighting was provided by the guides who carried lanterns and magnesium torches or flares. Electricity was connected in 1920 when a generating plant was installed, and this was used until 1969 when State Electricity Commission power was connected. Subsequently there has been much upgrading of the Caves and ancillary facilities. Wire netting was installed to protect the formations, and over the years obstructions have been removed, and board walks and concrete paths constructed to facilitate public inspection. In June 1907, Frederick Wilson was appointed Caves Supervisor. In July 1918, a committee of Management was constituted which continued until its reconstitution in 1946.

The camping reserve at Buchan Caves was proclaimed in 1930, and in August, Hugh Linaker was commissioned to landscape the reserve. In December 1938, the Buchan Caves National Park was officially opened. According to the article ‘Buchan Caves Attract the Tourist’, in the 1975 edition of Landmark, the journal of the Department of Crown Lands and Survey, the Buchan Reserve comprises some 280 hectares. Aitken (1994) claims 285 hectares. In May 1939, a new electricity generating plant was installed at the the Buchan Caves reserve at a cost of some £1,473/7/7 (The Argus, 13/5/1939).

In 1946, an Advisory Committee, under the chairmanship of EJ Pemberton, was formed to advise the Department of Crown Lands and Survey, on the development, maintenance and supervision of the caves. In 1951, the advisory committee comprised representatives from the Departments of Lands and Survey; Public Works; Victorian Railways, and a Lands Officer from Bairnsdale (Swift, 1951: 6).

Boadle (1991) produced a draft management plan for the karst and cave resources in the Buchan and Murrindal area. In that plan, it was stated that the Buchan Caves Reserves consist of nine separate blocks, the largest being immediately west of the Township of Buchan, generally known as the ‘Buchan Caves Reserve’. Boadle (1991: 44) recognized the important role played by visitor facilities and services at the Main Reserve, and a draft management plan highlighted the need for information provided to be of a high standard, and recommended the production of a high quality brochure for tourists. The plan acknowledged that the Main Reserve was a focus of tourist activity, and an educational centre visited by many secondary and tertiary groups.

In 1994, Richard Aitken prepared a Classification Report for the National Trust of Australia (Victoria) of the Buchan Caves Reserve. Aitken considered the Buchan Reserve ranked second to the Jenolan Caves Reserve in New South Wales, in terms of its contemporary popularity, impact on local and regional development, surviving attributes and historical importance. He noted that the Buchan Reserve contains many fine examples of protective features, and the period and nature of the tourist development is comparable with places such as Mt Buffalo Chalet. A notable feature of the Buchan Caves Reserve is the degree to which it has been modelled on the United States of America National Parks Service, particularly the adoption of ‘parkitecture’ styles for some of its buildings.

In 1995, the Buchan Caves Committee of Management received a grant of $6,000 from the National Estates Grant Program. The project involved the production of an interpretative display located at the Buchan Caves Reserve, focussing on the significance of Aboriginal culture in the Buchan area, particularly Cloggs Cave (Calnin, 1997). It was emphasized in the application that the Aboriginal heritage of the Buchan district was something the visitors to the Buchan Caves complex were ‘not normally exposed to’. The ‘Cloggs Cave interpretation sign’ was installed at the Buchan Caves Reserve in August 1996. The text of the sign is presented in Appendix 3.1.

3.4 Fourth Phase: Duplication

MacCannell’s (1976) fourth phase in the development of attractions is that of ‘duplication’, when copies of the nucleus of the attraction, in this case the caves, are made available through media such as paintings, photographs, and postcards.

The first photographic reproductions of scenery in the Buchan Caves district were taken in early 1873 by a Mr. F. Cornell. ‘The series includes views of the Buchan Station, the workings of the Buchan Lead and Silver Mine, Back Creek, and of an exquisite little waterfall immediately adjacent thereto; also a view of the entrance to the celebrated Murrindal Cave, and one actually taken within the cave, which represents the pulpit rock’ (Gippsland Times, 25/2/1873).

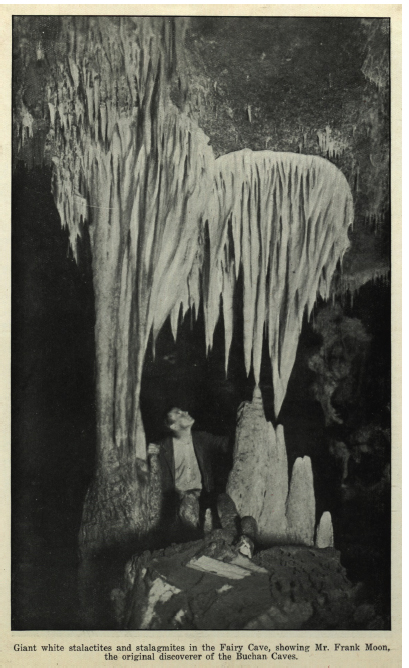

At the sixth annual exhibition of the Amateur Photographic Association, held at the Athenaeum in Melbourne, Mr. J.H Harvey, the Secretary of the Society, had a half dozen views of the Buchan Caves taken by the magnesium riband (see Fig.3.3). ‘The illustrations were extremely well executed, the various parts of interest, the stalactites, the stalagmites, the side chambers of the caverns, the limestone formations being delineated with exactness’ (North Melbourne Advertiser, 19/9/1890).

The Bairnsdale Advertiser and Tambo and Omeo Chronicle (10/8/1897) reported that some fine views of the interior of the Buchan Caves and of the picturesque spots in their vicinity had been taken by Messrs Ward Bros., of Bairnsdale.

In 1906, the Bairnsdale Advertiser and Tambo and Omeo Chronicle included an interior scene of one of the Buchan Caves in a series of 35 “postcards” of views now on sale at The Advertiser office for 9d a dozen (Bairnsdale Advertiser and Tambo and Omeo Chronicle, 26/4/1906). The following year, “Views of the Buchan Caves and Pyramids,” was compiled by F. Verrell Heath, and published by T.C. Lothian, Melbourne (Gippsland Times, 11/4/1907). The same year (1907), F. Whitcomb released Guide to Buchan Caves and Gippsland Lakes, and included photographs by H.D. Bulmer and N.J. Caire and was published by the Cunninghame Progressive Association.

In 1926, The Argus reported that C.H. Herschell had taken films of the interior of the Buchan Caves. ‘The caves have never been filmed before, and magnesium flares of the kind used to make motion pictures of forests by night in America were fired’ (The Argus, 5/2/1926).

3.5 Fifth Phase: Social Reproduction

For MacCannell (1976), the final stage of sight sacralization is social reproduction which occurs when groups, cities, and regions begin to name themselves after famous attractions. In the case of Buchan, the name is found in the Buchan pastoral run, first taken up in early 1839, Buchan River, and Buchan township. In 1935 the Buchan Hotel was changed to the Caves Hotel (The Argus, 18/6/1935). Since 1935 the hotel’s name was changed to Buchan Caves Hotel, its current name. It is also possible to identify numerous business that include Buchan in their business names, such as Buchan Valley Log Cabins; Buchan Lodge; Buchan Motel; Buchan Cottage,

3.6 Tourism at Buchan Caves

The first mention in tourism literature of tourism at the caves dates from Bailliere’s Victorian Gazetteer and Road Guide of 1879 where mention is made of caves near Buchan (Aitken, 1994). Similar brief references to the ‘famous Buchan caves’ appeared in Pickersgill (1885). However, the earliest known reference to tourist use of the caves is believed to be R.S. Browne’s (1886) Our Guide to the Gippsland Lakes. In July 1887, the Bairnsdale Advertiser and Tambo and Omeo Chronicle notified its readers that Edward Foley, the local mail contractor, had placed a coach on the line between Buchan and Bruthen and those desirous of visiting the far-famed Buchan caves were able to make reservations with the contractor.

The Bairnsdale Advertiser and Tambo and Omeo Chronicle (4/3/1902) reported on a plan by the proprietor of Lake Tyers House to link tourism at Lake Tyers with that at Buchan.

The Argus summarized the state of tourism to the caves in 1914:

As evidencing their growing popularity of the Buchan Caves now recognised as one of the ‘show places’ of Victoria, the increase in the number of visitors this year is very satisfactory. During January 370 admission fees were paid and during February 251. Since the caves were opened six years ago the total admissions have numbered about 8,000. In the immediate vicinity of Buchan there are now four caves open-Fairy, Blackwood, Royal and Moon Caves. By the opening of the Royal Cave during this tourist season some of the most beautiful chambers containing exquisite limestone formations have been made available to visitors. ... Many of the visitors consider these formations rival those of the Jenolan Caves. By the recent developments the value of Buchan as a tourist resort has been very much enhanced and the extent of cave passages now fully opened up and easily accessible will provide ample enjoyment for visitors for many hours. It is no longer possible for visitors to view the caves as they should be seen by merely staying in the township one night. Tourists should arrange to devote several days to their inspection (The Argus, 17/3/1914).

Following from this report, The Argus published letters from two correspondents who bemoaned the fact that although they had purchased tickets they were constrained by the limited number of conveyances to take them to the Buchan Caves from Cunninghame. They were also critical of the state of the road from Nowa Nowa to Buchan. The first correspondent, from Kyneton, closed his letter stating ‘Present conditions will not conduce to the desire for a second visit’ (The Argus, 21/3/1914). The second correspondent, from Geelong, agreed with the Kyneton writer (The Argus, 24/3/1914).

The Malvern Standard (26/4/1919) reported that year by year ‘the number of tourists who visit the Buchan Caves is increasing. The summer months are the favourite times for making the visit, which is well repaid by the splendid scenery that abounds en route, not to speak of the pleasure derived from an inspection of the caves. Buchan is reached in one day from Melbourne by taking train from the central station to Nowa Nowa, at the head of Lake Tyers, where motorcars are in readiness to take tourists to their destination’.

In February 1922, The Daily News reported on the state of tourism at the Buchan Caves:

These caves, taken under control only a few years ago, have been so highly developed, and opened up by safe, clean, easily traversed and airy passages, that, without effort and under conditions of comfort, young and old may now explore these wonders of nature which, seen under the bright electric light, or the still brighter blaze of the magnesium light, have delighted tens of thousands of visitors, and annually attract thousands to this fascinating resort. ... A great error is made by hundreds of tourists, who are led to believe that the caves can be inspected in an hour or two, and plan their tour accordingly for just a flying visit. Considering the distance to be travelled, and the expense involved, this should be avoided. As the length of the passages opened up for the convenience of visitors is over one and a half mile, it is very evident that considerable time should be given for a reasonable and satisfactory examination. Again, a popular idea is that to see one cave is to see all. This is another decided mistake for, strange though it may appear, and incapable of explanation, all the caves differ very much in their formations. True, stalactites and stalagmites are in all, but in shape, color, and variety of form, they are distinctly dissimilar. A proper inspection of any of the principal caves will occupy from 1½ to 2 hours, and then it is quite time for the visitor to go out into the open air, when he may enjoy the freshness and charm of the park-like reserve, which now has a very fine avenue of eucalypts, acacias and other varieties of trees as a means of approach to the different cave entrances. Kangaroo and emu have been introduced into the reserve, and at times these are to be seen along the avenue. The principal caves in the Buchan Park are Fairy, Blackwood, Royal, Federal and Moon, the first discovery being the Fairy. … In the Buchan Caves the State of Victoria has a natural asset of incalculable value, one that is worthy of the utmost care and the highest standard of development (The Daily News, 21/2/1922)

In January 1924, Frank Moon, the caretaker, discussed entrance fees and other grievances from tourists and gave some inkling of visitor satisfaction from visiting the Buchan Caves:

Sir,–As caretaker and guide to the Buchan Caves, I desire to reply to recent letters on charges for admission. The caves are open for inspection on all week days at 10.30 a.m., 2.30 p.m., and 7.30 p.m. The admission to the two principal caves–Fairy and Royal–is 2/6 for each person. Mr Shaw is correct in saying that people are charged 3/- for the evening visit. Half the above fees are charged for persons under 14 years of age. For other caves of less importance the charges are 1/6 and 1/-. Visitors frequently attack me about the bad state of the Ironstone crossing and Flourbag Hill between Nowa Nowa to Buchan. The continual “nagging” accounts for the guide ‘holding forth’ to that memorable assemblage referred to by Mr Shaw, who says that I stood on an eminence. As a matter of fact, I was standing alongside “Lot’s Wife,” and she did not even blush. I told those present to air their grievances through the press. Speaking with an unbiased mind, I find it impossible to make any comment or comparison between Buchan and Jenolan cave systems. Both are extremely beautiful and instructive. I would strongly advise any person wishing to have “a cheap 2/6 worth” to visit these beautiful Buchan Caves, and see for themselves. The usual comment from thousands of visitors is thus–Worth a ‘quid’ of any man’s money. Good-bye old chap. I will see you again at Easter. I am going to bring my friends “-Yours &c. Buchan; Jan. 15. FRANK H.A. MOON (The Argus, 18/1/1924).

In 1926, the Swanston Motor Tourist Bureau was offering tours, inclusive of accommodation, to the Australian Alps, Mount Buffalo, Omeo, Gippsland Lakes, and Buchan (8 days, cost £12.10s), and to the Gippsland Lakes and the Buchan Caves (8 days, £9.10s) (Wells, 1986: 258).

In 1936, Winifred Moore published the following account of a guided tour of the Buchan Caves: she waxed lyrically of the role of the guide, Frank Moon:

As one who was instrumental in discovering and helping to develop the caves, our guide, a man named Moon, had a personal interest in his job, and having only our small party to conduct he was in fine form. Though he has been showing people through these caves for the greater part of his life — interrupted only by a break while on active service in France— familiarity has not dulled his enthusiasm. His wife and three daughters – apparently share this also, for with great pride he pointed out the very place in the cave in which one of his daughters—’Fairy Moon’–had actually been married to one of the younger guides. He himself, he said, had wished to be married in Fairy Cave, but the Government of the time, less broad-minded than that of to-day, had refused permission for the ceremony in such a place. ... So enthusiastic was our guide that as we splashed through the stream of seepage water he would call a halt now and then, and manipulating the red and white lights at a nearby switchboard, would direct our attention to the beautiful reflections made by the grottoes in the muddy stream at our feet. ... With his colleagues he had shown more than 600 visitors through the various caves on one day early in January, and even at the time of our visit, in the off season, he was busy explaining all their marvels to an average of between 60 and 70 tourists daily (The Courier-Mail, 20/2/1936).

In 1988, a Far East Gippsland Tourism Strategy was produced and Buchan was identified as a ‘tourism hub’.

Visitation through the show caves during the decade 1981-91 averaged 85,082 people per year, with approximately 160,000 visiting the Main Reserve each year (Boadle, 1991: 41).

The Bataluk Cultural Trail is a collaborative project between five Aboriginal community organizations in East Gippsland and local government, concerned with cultural and eco-tourism. The trail integrated 12 separate cultural sites, stretching from Sale to Cann River, and included the Buchan Caves. Brochures were published and distributed from May 1995 (East Gippsland Institute of TAFE, 1996: 13). The trail was officially launched on 27 October 1995.

In October 1996, Urban Spatial and Economic Consultants Pty Ltd (USEC) completed an audit of the tourism infrastructure of Gippsland. They identified the Bataluk Cultural Trail had state-wide significance (USEC, 1996: iii). The Bataluk project was prioritized as it offered the visitor to Gippsland a unique Aboriginal perspective. They considered the trail required minimal capital input and provided opportunity and flow on effects for the Aboriginal population of the region (USEC, 1996: 22). In an analysis of the trail, USEC (1996: 85) claimed that Buchan was ‘where aborigines would retreat for the winter months and live in caves’. In 1997, Urban Spatial and Economic Consultants Pty Ltd (USEC) produced a regional tourism development plan for the Lakes and Wilderness tourism region. In terms of Indigenous issues, the plan (USEC, 1997: 10) acknowledged that ‘Lake Tyers and Buchan were significant current Aboriginal tourism areas’. Aboriginal tourism, via the Bataluk Cultural Trail, was identified as a product strength of the region. The development plan recommended the development of the Snowy River as a ‘heritage icon’; development of the Buchan township and Buchan Caves as a heritage precinct for the region; and further expansion of the Bataluk Cultural Trail (USEC, 1997: 40).

In December 1997, the Department of Natural Resources and Environment and Parks Victoria (NRE & PV) produced an ecotourism strategy for Far East Gippsland, for Parks Victoria and the Department of Natural Resources and Environment. It was found that approximately 472,000 people annually visited public land in East Gippsland, 332,000 to parks and reserves, and 140,000 to state forests (NRE & PV, 1997: 8). In relation to Buchan, the caves reserve was recognized as a regional example of a natural area intensively managed for high levels of recreation. The caves in the Buchan –Mid Snowy River area were recognized for their geological values, and ‘many have a history of aboriginal use as well’ (NRE & PV, 1997: 19).

The ecotourism strategy noted that in recent years interest in experiencing Aboriginal art, history and culture had increased (NRE & PV, 1997: 21). In terms of visitor amenities and services, opportunities were found to exist for on-site information boards, interpretive walks, and guided tours and activities. Along existing tourist drives and key walking tracks more on-site interpretation facilities were recommended. Aboriginal culture was identified as one of the more popular themes to be considered (NRE & PV, 1997: 36). Guided tours based on Aboriginal culture were seen as an opportunity. A special event based around the Bataluk Cultural Trail was another possibility. The Strategy encouraged Aboriginal communities to explore the benefits they may derive from further involvement with cultural tourism (NRE & PV, 1997: 44).

3.7 Conclusion

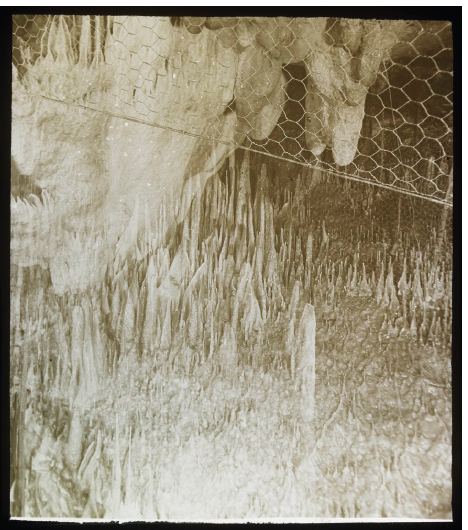

Although the presence of caves in the Buchan district was first mentioned in 1840, the first known visit from staff from the Surveyor-General’s department did not take place until 1854. Nascent tourism began to occur from the 1870s. In 1889 the first systematic geological survey was undertaken and recommendations made to develop the site into a tourist attraction similar to the Jenolan Caves in New South Wales replete with a caretaker and the installation of electricity. Further recommendations by a geologist with the Mines Department in 1900 saw the reservation of some 65 hectares of Crown Land near Buchan by the Department of Crown Lands and Survey in 1901, and an additional 48 hectares in 1902. The camping reserve at Buchan Caves was proclaimed in 1930 and in 1938 the Buchan Caves National Park was officially opened (see Fig.3.4).

The two show caves at Buchan, Fairy Cave and Royal Cave, were ‘discovered’ in 1907 and 1910 respectively. The opening to the Fairy Cave was enlarged using some gelignite and after the construction of pathways and wire netting to protect the stalagmites and stalactites, cave was opened to the public in late 1907. Royal Cave was opened in late 1913 after reserve employees cut through a solid block of marble and used a large quantity of explosives to blast through 150 feet of rock. In 1920 a generating plant was installed at the complex which remained in use until 1969 when the site was connected to the state electricity grid. A notable feature of the Buchan Caves reserve is that it has been modelled on the United States of America National Parks Service, especially its adoption of ‘parkitecture’ styles for some of its buildings.

In terms of the agencies responsible for the protection and development of tourism at the site, it is possible to identify a mixture of government departments and geologists, the local Buchan community, regional progress association, and key inviduals such as Frank Moon.

The Buchan Caves have significant Aboriginal values, especially the widespread heritage of caves as places where the Nargun and wicked and mischevious Nyols lived. For this reason Aboriginal people were not in the habit of venturing deep into the limestone caverns.

References

Aitken, R. (1994). Classification Report – Buchan Caves Reserve. Melbourne: National Trust of Australia (Victoria).

Austin, P. (1992). A Dictionary of Gamilaraay Northern New South Wales. Bundoora: Department of Linguistics, La Trobe University.

Australasian Sketcher with Pen and Pencil 28/8/1880.

Bairnsdale Advertiser and Tambo and Omeo Chronicle 2/5/1889; 10/8/1897; 18/1/1902; 4/3/1902; 15/4/1902; 19/4/1902; 29/4/1902; 26/8/1905; 22/2/1906; 26/4/1906; 6/12/1906; 19/3/1907; 23/3/1907; 4/4/1907; 23/12/1911.

Billis, R.V. & Kenyon, A.S. (1974). Pastoral Pioneers of Port Phillip. Melbourne: Stockland Press.

Boadle, P. (1991). The Management of Karst and Cave Resources in the Buchan and Murrindal Area. Draft prepared for the Bairnsdale Region Department of Conservation and Environment, September.

Browne, R.S. (aka Tanjil). (1886). Our Guide to the Gippsland Lakes and rivers … Melbourne: M.L. Hutchinson.

Buchan Sesquicentenary Committee. (1989). Bukan-Mungie 150 years of Settlement in the Buchan District – 1839-1989. Buchan: Buchan Sesquicentenary Committee.

Bulmer, H.D. (n.d.) Beautiful East Gippsland containing views of Bairnsdale along the Prince’s Highway The Lakes and Buchan Caves. Bairnsdale: Howard D. Bulmer.

Calnin, D. (1997). National Estates Grant $6000 Interpreting Aboriginal Significance – Buchan. A Report to National Estates Grant Program, 2 pp.

Clark, I.D. (1998a). Place Names and Land Tenure – Windows into Aboriginal Landscapes: Essays in Victorian Aboriginal History. Melbourne: Heritage Matters.

Clark, I.D. (ed.) (1998b). The Journals of George Augustus Robinson, Chief Protector, Port Phillip Aboriginal Protectorate, Volume 4: 1 January 1844 – 24 October 1845. Melbourne: Heritage Matters.

Department of Lands and Survey. (c.1909). Victoria’s Tourist Resorts. The Buchan Caves. Melbourne: Department of Lands and Survey.

Department of Crown Lands and Survey. (1975). Buchan Caves Attract the Tourist. Landmark The Journal of the Department of Crown Lands and Survey, 1:10-12.

Dixon, R.M.W. & Ramson, W.S. & Thomas, M. (1992). Australian Aboriginal Words in English – Their Origin and Meaning. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Douglas, J.G. (n.d.). Buchan Caves: A Geological Discussion, Revised from original of JA Talent. Melbourne: Department of Minerals and Energy, Victoria.

East Gippsland Institute of TAFE. (1996). Bataluk Cultural Trail Cultural Mapping Project, Final Report for The Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation, Bairnsdale, January.

Fison, L. & Howitt, A.W. (1880). Kamilaroi and Kurnai. Melbourne: George Robertson.

Gardner, P.D. (1992). Names of East Gippsland; their origins, meanings and history. Ensay: Ngaruk Press.

Gippsland Times 25/2/1873; 5/7/1873; 15/4/1878; 29/5/1885; 25/2/1889; 12/3/1890; 15/10/1906; 8/4/1907; 11/4/1907; 10/1/1946.

Heath, F.V. (1907). Views of the Buchan Caves and Pyramids. Melbourne: TC Lothian.

Henderson, K. & de Quadros, M. (1993). The Buchan & Murrindal Caves East Gippsland, Victoria. Williamstown: Henderson de Quadros Publications.

Howitt, A.W. (1904). The Native Tribes of South East Australia. Melbourne: Macmillan and Company.

Lavelle, R.H. (1952?). Buchan Caves Victoria Australia: Australia’s Most Wonderful Caves. Unpublished draft manuscript in Parks Victoria archived file Buchan Caves File No. 41 (see below).

MacCannell, D. (1976). The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class. New York: Schoken

Massola, A. (1968). Bunjils Cave: myths, legends and superstitions of the Aborigines of South-East Australia. Melbourne: Lansdowne.

Minister of Lands. (c. 1925). Buchan Caves. Melbourne: Published by authority of the Hon. The Minister of Lands for issue to tourists, Government Printer.

Moon, R. (1985). Buchan Caves, more than just holes. The Age, 8/2/1985.

Morgan, P. (1997). The Settling of Gippsland A Regional History. Traralgon: Gippsland Municipalities Association.

North Melbourne Advertiser 19/9/1890.

NRE & Parks Victoria. (1997). Far East Gippsland Ecotourism Strategy. Orbost: Department of Natural Resources and Environment/Parks Victoria.

Pepper, P. & De Araugo, T. (1985). What Did Happen to the Aborigines of Victoria, Volume 1: The Kurnai of Gippsland. Melbourne: Hyland House.

Pepper, P. & De Araugo.T. (1989). You are what you make yourself to be: the story of a Victorian Aboriginal family 1842-1980. Melbourne: Hyland Press.

Pickersgill, J. (ed.) (1885). Victorian Railways tourist’s guide: containing accurate and full particulars of the watering places, scenery, shooting, fishing, sporting, hotel accommodation, etc. in Victoria … Melbourne: Sands & McDougall.

Roberts, L. (1977). A brief history of Buchan district and schools prepared for the Buchan school centenary. Buchan: Buchan School Committee.

Ryrie, S. (1840). Journal of a tour in the Southern Mountains, Ref. No: ADD 204, Dixon Library, State Library of New South Wales [Reprinted Gippsland Heritage Journal, December 1991, 11:11-17].

Salierno, A. (ed.). (1987). East Gippsland Past and Present. Victoria: F. Amendola.

Seddon, G. (ed.). (1989). The Ballad of Bunjil Bottle; AW Howitt’s exploration of the Mitchell River by canoe in 1875. Churchill: Centre for Gippsland Studies, Gippsland Institute of Advanced Education.

Seddon, G. (1994). Searching for the Snowy: An Environmental History. St Leonards: Allen & Unwin.

Smyth, R.B. (1878). The Aborigines of Victoria, with notes relating to the habits of the natives of other parts of Australia. 2 Vols. Melbourne: Victorian Government Printer.

Swift, D. (1951). Buchan – Valley of Caves. Melbourne: Buchan Caves Advisory Committee, Department of Lands and Survey. [Reprint from Mining and Geological Journal, 1:4, September 1951].

The Argus 17/11/1854; 22/5/1886; 10/4/1902; 3/10/1906; 11/10/1906; 25/10/1906; 5/4/1907; 27/5/1907; 29/11/1907; 19/11/1910; 17/3/1914; 21/3/1914; 24/3/1914; 11/10/1918; 18/1/1924; 5/2/1926; 25/7/1931; 1/8/1931; 18/6/1935; 24/11/1937; 2/12/1938; 13/5/1939; 16/11/1951.

The Malvern Standard 26/4/1919.

Urban Spatial and Economic Consultants Pty Ltd. (1996). Gippsland Tourism Infrastructure Audit. October. West Melbourne: Urban Spatial and Economic Consultants Pty Ltd.

Urban Spatial and Economic Consultants Pty Ltd. (1997). Lakes and Wilderness Regional Tourism Development Plan. September. West Melbourne: Urban Spatial and Economic Consultants Pty Ltd.

Wells, J. (1986). Gippsland: a place, a people and their past. Drouin: Landmark Press.

Whitcombe, F. (c. 1907). Guide to Buchan Caves and Gippsland Lakes, illustrated by HD Bulmer and NJ Caire. Cunninghame: Cunninghame Progressive Association.

Government Departmental Files

Parks Victoria Files: Buchan Office

Buchan Caves Reserve: Publicity’, Department of Lands and Survey, Archived file, Buchan Caves File No. 41.

‘Caves and Tourism’, Department of Lands and Survey, Archived file, no file number.

Appendix 3.1 Intepretive Signage Installed in 1996

People in the Ice Age

–Who lived here?

Aboriginal people from the Ganai (or Kurnai) and Bidiwal nations lived in the Buchan area. They moved around in small bands of several families, and set up base camps from time to time to exploit the local resources. The open grasslands of the Ice Age made good hunting grounds. But people also needed shelter, access to water and corridors for travel. This made the few caves and rock shelters close to streams ideal places to live.

–Where and how did they live?

One of the most significant Ice Age human occupation sites in Victoria is at Clogg’s Cave on the Buchan River. Starting around 18,000 years ago, people lit campfires inside the cave for warmth and cooking food such as possums, wallabies, kangaroos and koalas. The cleaned animal skins were rubbed with burnishing stones until soft, cut into shape using sharp quartz flakes, and then sewn together using bone awls and sinews from kangaroo tails to make cloaks. But when the Ice Age finished some 13,000 years ago, Clogg’s Cave was abandoned until 1,000 years ago when local Aboriginal people occasionally used it during hunting expeditions. This long history makes Clogg’s cave a very important place for present-day Aboriginal people.

– Aboriginal people today

The local aboriginal communities invite you to find out more about their rich history, heritage, and culture at some of the region’s aboriginal cultural centres:

– Ramahyuck Aboriginal Corporation, Sale

– Krowathunkoolong (the Keeping Place), Bairnsdale

– Moogji Aboriginal Council, Orbost

– Nulluak Gungji, Cann River

The Bataluk Cultural Trail of East Gippsland also provides a fascinating discovery of local Aboriginal heritage. Enquiries can be made at any of the above centres.

Funded by Australian Heritage Commission National Estate Grant Program

Fig.3.1: The Font of the Gods, Royal Cave, Buchan. Showing the Twelve Apostles (Source: Bulmer, N.D.)

Fig. 3.2: Giant white stalactites and stalagmites in the Fairy Cave, showing Mr. Frank Moon, the original discoverer of the Buchan Caves. Source: Bulmer, N.D.

Fig. 3.3: Buchan Caves, glass lantern slide by John Henry Harvey, J.H. Harvey Collection, State Library of Victoria Pictures Collection.

The slide shows wire netting installed to protect the stalactites.

Fig. 3.4: The Entrance to Buchan Caves National Park, c. 1948, Postcard: Gelatin silver photograph. State Library of Victoria Pictures Collection H95.28/6

9 A copy is on file at the Parks Victoria Buchan Office. It was Lavelle’s intention to submit the manuscript to the London magazine, Wide World Magazine. It seems it was never published.

10 F. Cornell, a photographer.