7 Mount Buninyong Scenic Reserve by Jaimie Watson and Ian D. Clark

This chapter provides a historical examination of Mount Buninyong, tracing its evolution from an Aboriginal cultural site into a recreational tourist attraction. It follows the example set by Clark’s (2002) study of the evolution of Lal Lal Falls as a tourism attraction and documents the development of Mount Buninyong as a tourism attraction with significant consideration of key moments such as the first accounts of European visitation in 1837, its declaration as a public reserve in 1866, and the year 1926 when a road was built to the summit. To understand the history and evolution of tourism visitation to the Mount, this chapter will explain this transition by showing the significance of the works provided by MacCannell (1976; 1999), Butler (1980) and Gunn (1994). It will demonstrate that when these theoretical models are combined they contain explanatory materials capable of comprehending the history and evolution of a natural and cultural tourism attraction. MacCannell’s studies into the development of secular attractions suggest they go through five stages including sight sacralization and/or naming, framing and elevation, enshrinement and duplication or mechanical reproduction, and finally social reproduction. Butler’s tourism area life cycle model may explain the succeeding stagnation and rejuvenation of the Mount. Gunn’s spatial model of three zones of visitor interaction should provide an understanding of the evolution and history of planning at Mount Buninyong.

Mount Buninyong is an extinct cinder cone volcano located 15 kilometres south east of Ballarat near the township of Buninyong. The summit of the mountain is between 719 and 745 metres above sea level and overlooks the City of Ballarat offering 360 degree views of the goldfields region (City of Ballarat, 2012). Mount Buninyong was created by an accumulation of cinder rocks that were ejected during explosive volcanic eruptions. Cinder cones generally range from about 50 to 200 meters in height, and consist of a steep sided mountain with a rounded top (Geocaching, 2008). Two types of rocks were produced from the volcano, cinder and basalt; both of which are hardened lava. The difference is scoria is blasted into the air which causes air bubbles to form making it light, while basalt is formed from lava flows that runs along the ground caused by the heaviness of the flow (Geocaching, 2008). Two separate volcanic cones exist at Mt Buninyong. The volcanic cone that is visible on site is the most recent, while the older volcanic cone has been destroyed mostly due to the eruption of the newer cones and erosions (Geocaching, 2008). The first volcanic cone at Mount Buninyong was created between 100 000 and 150 000 years ago, while the second cone occurred only 12,000 years ago (Geocaching, 2008). Mount Buninyong when it was an active volcano produced lava flows in two different directions; first to the East out of a flank crevice in the side and to the West over the summit of the volcano. These lava flows produced large lava plains at Lal Lal Falls (Clark, 2002). Mount Buninyong is an important refresh point for the groundwater system of the surrounding volcanic plains due to its highly permeable scoria cone. Springs are found at the base of the Mount where the more recent volcanic material rests on the underlying Ordovician frame (City of Ballarat, 1997).

Mount Buninyong is situated within the traditional country of the Wathawurrung Aboriginal people, and is one of Victoria’s most significant geological sites. The area surrounding Mount Buninyong formed the estate of the Keyeet baluk, a sub-group of the Burrumbeet baluk clan, that was centred on lakes Burrumbeet and Learmonth (Clark, 1990). The Australian Heritage Commission has stated that it is possible that Aboriginal cultural values of national estate significance may exist for the Mount also (City of Ballarat 1997).

7.1 First Phase: Sight Sacralization and Naming 1837–1866

MacCannell (1976) has identified the first phase in the development of secular attractions as sight sacralization or naming. This takes place when a sight is marked off from similar objects worthy of preservation or the site has been given a name (MacCannell, 2001). Clark (2009) makes note that the naming of a place plays a vital role in the development of tourist attractions, and suggests ‘If the names of sites are dysfunctional and fail as informative markers and conjure expectations that are not met, then names can become management problems and contribute to graffiti, vandalism and destruction and negative word of mouth publicity’. In relation to Gunn’s (1994) spatial model of three zones of visitor interaction, the site is the ‘nucleus’ of the attraction; the main focus of tourist interest. In this case it would be Mount Buninyong itself. Butler’s (1980) tourism area life cycle model can help to clarify these phases with his ‘exploration’ stage in which tourism is promising and visitor numbers are growing yet insignificant, a stage similarly described as ‘pre-tourism’.

Buninyong is an Aboriginal toponym. There are variant spellings in the literature including Boning Yong; Bonningyong; Bun.un.yong; Bunin-youang; and Bunningyowang. The earliest translation of the place name is provided by Katherine Kirkland (1845) who believed it meant ‘big mountain’.

We were now in the Boning Yong district, which takes its name from a very high mountain, on the top of which is a large hole filled with water. It is quite round, as if made by man, and there are fish and muscles [sic] in it. Boning Yong is a native name, and means big mountain. I like the native names very much: I think it is a great pity to change them for English ones, is as often done (Kirkland, 1845: 27).

Andrew Porteous (in Smyth, 1878 vol. 2: 179), who was the local guardian for the northern Wathawurrung in the 1860s and 1870s in the Carngham district, analysed the meaning of Buninyong as ‘man lying on his back with knees raised’. William Withers (1887: 13), in his local history of Ballarat, claimed the name had the following origin:

Buninyong, or, as the natives have it, Bunning-yowang, means a big hill like a knee – bunning meaning knee, and yowang meaning hill. This name was given by the natives to Mount Buninyong because the mount, when seen from a given point, resembled a man lying on his back with his knee drawn up.

Aldo Massola’s (1962: 111) gloss was ‘knee mountain’, with links to the myth he learnt from Annie Alberts; the name means ‘knee’ since the mountain looks like an Ancestor lying down with his knee raised. Les Blake (1977: 182) translated it to mean ‘man lying on back with raised knees’. The word for ‘knee’ in Wathawurrung is ‘pun/bun’ (Hercus, 1999). Barry Blake’s analysis is that it means ‘with his/her knees’ (Clark & Heydon, 2002). Clark and Heydon’s (2002) database of Victorian Aboriginal place names, confirmed that the name Bun-a-nyung also referred to Mt Fyans Home Station near Darlington.

In terms of Aboriginal mythologies about the creation of Mount Buninyong, William Stanbridge (1861) has published the following account he received from tribes in the neighbourhood of Fiery Creek. The account is interesting as it links two volcanoes together – mounts Elephant and Buninyong:

One of the legends that these tribes are fond of relating is, that Tyrrinallum (Mount Elephant) and Bouningyoung (two volcanic hills about thirty miles apart) were formerly black men, that they quarrelled and fought, the former being armed with a leeowil and the latter with a hand spear, and after a prolonged contest, Tyrrinallum thrust his spear in Bouningyoung’s side, the cause of the present hollow in the side of the hill, which so infuriated him that he dealt the other a tremendous blow, burying the point of the leeowil in his head, which made the present large crater, and knocked him to the spot where he now stands (Stanbridge, 1861: 300).

Massola (1962) recounted another version of this legend, told to him by Annie Alberts, who he considered to be the last full-blood Aborigine from the Western District. Albert’s version of the legend is as follows (Massola, 1962: 110):

Mount Elephant and Mount Buninyong were once men. Mount Elephant was in possession of a stone axe. Buninyong offered him some gold for it. Having agreed they met at what is now Pitfield Diggings for the exchange. Some time later Buninyong reconsidered, and desired his gold back. Elephant refused. Buninyong sent him a fighting message, and the challenge was accepted. They met at Pitfield Diggings. Elephant buried his spear in Buninyong’s side, and the hole can be seen to this day. Elephant received a deadly blow on the head from Buninyong’s stone axe. The gaping hole on Elephants head can also be seen to this day. The two men, mortally wounded, retired in opposite directions; their bodies turned into mountains, can be seen today at the spots where they died.

Massola (1962) comments that the newer version has ‘post-European components’, as gold was not valued in traditional times; it was only after the 1850s gold rushes that Aboriginal people began to value gold.

The first recorded European ascent of Mount Buninyong was in May 1837, when Frederick D’Arcy, a Government Surveyor, had learnt from the local Aborigines of the whereabouts of Mount Buninyong and Lal Lal Falls (Griffiths, 1988). D’Arcy, a surveyor, explored along the Moorabool River to Mount Buninyong. D’Arcy was accompanied by Dr Alexander Thomson and George Frederick Read, a prospective settler (Macqueen, 2010). George Frederick Read, who was accompanying D’Arcy on his expeditions and later become one of the earliest settlers of Buninyong, wrote the following journal account during May, 1837:

I went with Dr. Thomson and D’Arcy the surveyor exploring the country as far as Buninyong from which hill we saw some large lakes in the distance and a country similar to that we had gone through the day previous which was certainly most beautiful. Rode down an emu on the way the flesh of which when fried was palateable... (quoted in Griffiths, 1988: 1).

In August, 1837 another expedition party was formed, again including D’Arcy and Dr. Thomson as well as George Russell, David Fisher, Captain Hutton, Thomas Learmonth and Henry Anderson (Macqueen, 2010). The party was led by an Aboriginal guide. They headed towards Lal Lal Falls and to the foot of Mount Buninyong with a cart and tent; Learmonth noted that it was ‘the only hill that breaks the horizon to the north-west of Geelong’ (Bride, 1898: 39). The party was unprepared with supplies to continue the expedition, and as a result most of the party camped on the site which later became Andrew Scott’s ‘Mt. Boninyong’ homestead (Griffiths, 1988). Russell’s account of this experience is as follows:

We could see nothing of Mr D’Arcy’s party with the dray, and went about in search of them, firing off guns and pistols until it got dark; but we received no reply in the way of gun-shots, or any other sign that they heard us; and as the night was dark we made up our minds to spend it where we were. We gathered a quantity of logs together and made a large fire, and sat chatting away to each other until we got sleepy. Then we lay down on the grass with our saddles for pillows, all feeling the want of something to eat, having had nothing to eat since morning. We spent the night the best way we could. Fortunately, although it was dark and cloudy it was mild (Macqueen, 2010: 108).

Macqueen (2010: 108-109) also records Russell’s expedition climbing the mount:

At day break some of the party, of whom I was one, went to the top of Mount Buninyong to get a view of the country. Some of the party, from being so long without food, didn’t feel disposed for such a steep climb in the early morning.

Macqueen (2010: 109) questions whether their climb to the top of the mount was worthwhile, as he points out that as is the case today Mount Buninyong was covered in a ‘healthy forest of eucalypts which allowed only glimpses of the landscape beyond’.

Andrew Scott established his run on the eastern side of the Mount in 1839. He named his run ‘Boninyong’ as it is still called today, held by the same family. The marshy creek area nearby became known as Scott’s Marsh and later a community developed around the area that is now known as Scotsburn (DSE Heritage Database, 1998). The Chief Protector of Aborigines, George Augustus Robinson visited the Buninyong district in February and March 1840 and called on the Scotts. Robinson also acknowledged there was a ‘dray road’ which was used to fetch timber, he writes ‘this will become the road of the Buninyong settlers’. Regarding Mount Buninyong, Robinson (Jnl 11/2/1840 in Clark, 2000) noted ‘The top of and sides of the hill are thickly timbered so that it being difficult to get an extensive view and my horse, being unfit for riding, I declined ascending the top of the mountain’.

Springs at the base of the Mount were important sites for early settlement including three pastoral stations and the township of Buninyong (City of Ballarat, 1997). Thomas Learmonth estimated the Aboriginal population within a 48 kilometre radius from Buninyong was approximately three hundred people (Griffiths, 1988). Griffiths (1988: 4) makes note that the Aboriginal people of the Buninyong district did not have much interaction with the settlers but were ‘often tempted to help themselves to grazing stock’. Only one fatality is documented. In April 1838, Terence McManus, a shepherd employed by Thomas and Somerville Learmonth, was killed at a place later named Murdering Valley (Griffiths, 1988). Subsequently, it did not take the Aboriginal people long to begin trading with the settlers. In the same month, George Frederick Read recorded in his journal, ‘A great many natives came here today and exchanged skins for flour–they were extremely cunning’ (quoted in Griffiths 1988: 4).

In the 1840s timber from Mount Buninyong was cut by pit sawyers and splitters and sent as far afield as Geelong (DSE Heritage Database, 1998). Trial Saw Mills Company soon replaced them. A large steam saw mill operation developed into a selfcontained settlement at the eastern base of the Mount in the 1850s (City of Ballarat, 1997). The exposed east facade of Mount Buninyong remains as a legacy of this industry. In 1860 the Buninyong Borough successfully applied to secure the Mount as a Timber Reserve ‘for mining and other purposes’ (City of Ballarat, 1997: 10). Guidelines for timber harvesting were not clearly articulated or enforced, as a result within 30 years of European settlement Mount Buninyong was nearly stripped of trees (City of Ballarat, 1997).

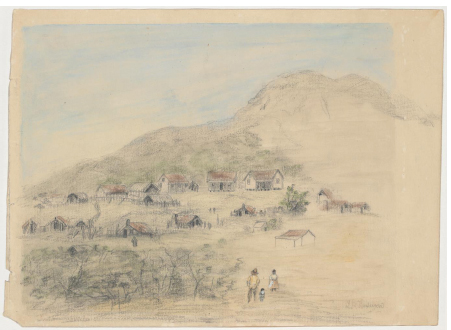

The township of Buninyong was surveyed in 1848 by W. Smythe. Accordingly land sales first took place in May 1851 (DSE Heritage Database, 1998). Records predate the discovery of gold on 9 August 1851 by Thomas Hiscock, the Buninyong blacksmith. The discovery of the Ballarat goldfield was a consequence of Hiscock’s find after he was searching for a stray cow (Beggs-Sunter, 2005). As a result, Buninyong developed and turned to the Mount as its symbol and icon, it was known as ‘the busiest town in Victoria outside Melbourne and Geelong’ (Beggs-Sunter, 2005) (see Fig.7.1). The seal of the first municipal council formed in 1859 depicted a rising sun behind the mountain (DSE Heritage Database, 1998).

Mount Buninyong’s significance lies with its cultural and natural values, however as Clark (2002) makes note, similar to Lal Lal Falls, it is interesting that apart from providing an Indigenous name for the mountain, Aboriginal cultural values were not influential in the sacralization of Mount Buninyong. European settlers were more interested in the natural values of the site.

7.2 Second Phase: Framing and Elevation 1866–1884

The second phase of MacCannell’s (1976) model of development of secular attractions is ‘framing and elevation’. MacCannell refers to elevation as putting an attraction up for display, in the case of Mount Buninyong opening the site up for visitation. MacCannell subsections this phase into two types: protecting and enhancing (MacCannell, 2001). In relation to Mount Buninyong, this phase began in 1866 with the site being declared a Public Reserve and ended with the development of an unsealed road in 1884 leading up to the mount’s summit (Leather, 2008). MacCannell’s framing and elevation phase correlates with Gunn’s ‘inviolate belt’ zone in his spatial model and in Butler’s ‘involvement’ stage in his life-cycle sequence. Gunn’s inviolate belt represents the area directly surrounding the nucleus of the site, Clark (2002: 5) describes it as ‘the psychological setting for introducing the visitor to the attraction’. Mount Buninyong being declared a Public Reserve in 1866 ensured that it would stop uncertainties of de-forestation of the site or allow settlers to infringe on the access to the summit (DSE Heritage Database, 1998). This period can also be associated with Butler’s ‘involvement’ stage, which is characterized by tourist visitations increasing and the formation of a significant tourism industry that develops around the attraction (Clark, 2002).

In 1866 Mount Buninyong was declared a Public Reserve, although as early as 1860 concerns were expressed about the de-forestation of the area. The reserve was for 247 acres after the Assistant Commissioner for Crown Lands wrote a report in 1865 advocating the need to place restrictions on timber harvesting because the removal of large trees had caused the understorey to disappear (DSE Heritage Database, 1998). Buninyong Municipal Council suggested that ‘It is the duty of this Council to take steps as deemed expedient for the purpose of securing not only the whole of Mount Buninyong, but all the timbered land within three miles of the municipality’ (DSE Heritage Database, 1998). Surrounding land was made available in 10 and 20 acre allotments to small landholders, who were usually dependent on a ‘Common’ to ensure their viability (City of Ballarat, 1997). A report in 1866 stated from the rush for 20 acre lots at Mounts Warrenheip and Buninyong ‘care should be taken that the recreational areas of the mount be not alienated and the district be thus deprived of its two most health giving summer resorts’ (Buninyong Municipal Council Minutes cited in DSE Heritage Database, 1998). For a number of years Mount Buninyong, as a Public Reserve, fulfilled this role. An early 1860s cottage still remains on the Geelong Road near Granny Whites Lane (City of Ballarat, 1997).

Edmund Leathes (1880: 35-9) has published an account of a visit to Mount Buninyong during a stay in Ballarat in the 1870s:

The drives around Ballarat were delightful; the most enjoyable of all was that to Mount Buninyong. It was a drive of some miles to the village which was at the foot of the mount; there we left our buggy and walked to the summit. It was hard work, but, when we got to the top at last, we were well repaid for our exertions. The view of the surrounding country, which was well watered and wooded, was magnificent in beauty and extent, regarded from all points. Standing on a pinnacle, as it were, we looked north, south, east, and west. The mountain itself was beautifully wooded, and, had it not been for the dread of snakes, the birds and foliage — the latter interlaced with flowering parasites — would have made the descent alone enjoyable.

From 1874 the Committee of Management for the Reserve formalised the grazing function and advertised for grazing tenders. For the following 90 years, until the early 1960s, Mount Buninyong was constantly grazed by stock. Surrounding areas were burnt at low intensity every few years during much of the grazing lease period (City of Ballarat, 1997).

In January 1877, a fire occurred at Mount Buninyong, The Argus recorded the following information:

A column of smoke was seen from Ballarat, arising from behind Mount Buninyong, between 9 and 10 o’clock last Saturday morning, looking, says the Star, as though the old volcano had once more awakened its died out fires. It could easily be seen, however, that the cause was a bush fire, and as the day grew the fire extended around the base and over the top of the mount, till at night the hill seemed covered with fire at almost every point seen from Ballarat. This prominent landmark in a blaze would have proved an interesting sight to onlookers had it not been for the thought that the farmers clustered around its base might lose by the fire the result of a year’s labour. The fire was gazed at by wondering groups of people at every point in the streets of the town whence a good view could be obtained and the wooded sides of the mount continued to keep up their bright appearance for four or five hours after dark, when they began to pale, till, when morning broke, nothing but a few thin wreaths of smoke could be seen curling up from the lower portions of the hill. On Sunday night a few trees that remained a light on the top showed out with special brilliancy against the sky. A large number of persons visited the locality on Sunday to see what damage the seemingly terrible conflagration had caused, but we are glad to say that the fire was almost entirely confined to the Government reserves, including the mount, and no farms were much damaged. This was the result of the incessant labours of everybody living about the mount, who turned out one and all to keep the fire from touching the crops, which in some places adjoined the reserves. In their endeavours they were successful, the fire, as we have said, doing little damage besides burning up the under- wood and fallen timber covering three-fourths of the mount, a portion of that side facing Ballarat being comparatively untouched. On the other side, where the fire began, it burned from base to summit, and only stopped for lack of fuel, having burnt in some places right under the fence to the edge of the No. 2 Railway road. It was on the other side, however, that the greatest danger was to be feared, as there the greatest number of farms are situated (The Argus, 22/1/1877).

The cause of the fire was arsonist and farmer, Joseph Innes, who lived at the bottom of the Mount. On 20 January 1877 he deliberately lit six to seven grass fires around the Mount in an attempt to create a severe amount of damage, which he evidently did. Innes was arrested and jailed for his crimes (The Argus, 22/1/1877).

In the 1880s the population of Buninyong was declining, with a population of 1450 in comparison to the estimated population in 1872 at 2000 (Griffith, 1988). The Telegraph noted ‘industry has dwindled down to a very small item. Farming, however, especially round the mount, has been going ahead’ (Telegraph quoted in Griffith, 1988). In 1884, celebrations for the proposed extension of the railway line to Buninyong occurred. Construction of a carriage drive to the crater, zigzag path to the summit, and the summit of Mount Buninyong was levelled to provide picnic and camp sites (Leather, 2008).

7.3 Third Phase: Enshrinement 1884–1960

The third phase of sacralization is ‘enshrinement’ which MacCannell (1999: 45) refers to when the framing material that is used has itself entered the first stage of sacralization’. Clark (2002) makes note that the phase applies when there is an increase in the numbers of tourists and the attraction’s reputation is increased. This phase is essential as it concerns the community services that are important to tourists (Gunn & Var, 2002). During this phase of enshrinement, the attraction developed its third spatial zone ‘zones of closure’. As summarized by Gunn it is an outer vicinity of community influence of travel structures such as land uses for modern travel services–in the case of Mount Buninyong the road and the rotunda. As Clark (2002) mentions this enshrinement phase also correlates with Butler’s ‘development’, ‘consolidation’ and ‘stagnation’ stages. These stages often happen very rapidly, tourism numbers significantly increase, and the tourism industry related to the destination dramatically changes. More than likely, the stagnation stage occurs represented by declining tourism numbers (Butler, 1980).

A significant period in regards to the enshrinement stage of Mount Buninyong was the tradition of New Year’s Day picnics. An example of the local tradition of ascending the mount is provided in the following account from Josiah Hughes (1891: 147-8):

On December 27th I went by rail to Buninyong, by appointment, where I met my cousin, Hugh Jones and his son, waiting for me, well stocked with Sandwiches and light refreshments, and equipped with a field-glass and stout walking sticks ready for the ascent of Mount Buninyong. Our way for a considerable distance was along the main road to Geelong, from which we turned to the left along rude country roads leading to the farm houses. In some places they were wellmade and kept in repair, but as we went on we left these behind and came to wide road reserves, wide enough for a dozen cartways, in a perfect state of nature, trees and saplings affording excellent shade from the hot sun, and the cartway winding in and out among them. It was now midsummer, and what was deep mud in winter was now fine dust, in some places 3 to 5 inches deep. After traversing this for about two miles we began to ascend in earnest, and it is surprising what an amount of country is revealed to one’s gaze in climbing this mountain, — unexpected valleys and hills of cultivated land, rugged precipices in unexpected corners; craters of extinct volcanoes, winding footpaths, giant trees, and fallen trunks of others, up to the very summit, which we reached by 12.45 noon. We were glad to rest ourselves with our backs against an enormous old tree, which lay there charred by the fires of many a pic-nic party. As we sat and refreshed ourselves with the good things provided, we were fanned by a deliciously cool breeze from the South, after which we got up and reconnoitred the surrounding landscape. The atmosphere was clear, and a great extent of country was visible, and with the assistance of our field-glass we could see to a great distance. As we sat at our refreshments, we faced Mount Warrenheip, about five miles off to N.N.E., with Mounts Hollow-back and Rowan and Spring Hill to the left at greater distances, the Black Hill, Mount Blackwood, Gordon’s, Mount Egerton, and Three Sisters to the S.E., with a magnificent plain of agricultural land between, mostly settled and cultivated, dotted over with trees, fences, homesteads and roads, especially along the Moorabool Valley, and nearly all to the eastward of the old Geelong road, to the township of Clarendon (old Corduroy). Beyond this to S.W. the land appeared poor and unsettled. We removed to another position and looked direct south, to Geelong, 50 miles away, without any interruption, with the fertile Barrabool Hills a little to the right, Mount Hesse, Gellibrand and Pollock almost due south by a little west, and Mount Elephant and the great lake Corangamite and its tributary rivers to the south-west. The country intervening between us and these objects for at least 20 miles is principally occupied by squatting stations with scarcely anything to indicate human occupation, the land being poor. After this we removed our standpoints to the highest ground facing north and north-west, where we could trace in the varying distances the great dividing ranges of the country, which govern the course of the rivers. Those on the North running inland to join the great river Murray, and those on the South, being the Werribee, the Moorabool, the Barwon, the Hopkins, etc. run direct to the Southern Ocean. From here we could recognise the whole of Ballarat, ten miles away, as if lying at our feet, with all the surrounding townships named after the various diggings or creeks which created them; and more to the north and north-west we saw fine arable, cultivated land, interspersed with poppet heads and mullock heaps, and other evidences of deep mining operations, reaching from Bullarook forest, to Smythesdale, taking in Mounts Blowhard, Bolton, Emu, and Lakes Learmonth, Burrumbeet, and Wendouree. As a majestic back ground to the whole, the great dividing range as far as the Pyrenees and the Grampians. I am well aware that this description is more or less unintelligible to most people, and that it is impossible to realize it without some acquaintance with the country; but it is possible that some of my younger readers will have the opportunity, and to those who will ever visit Ballarat my advice is, ascend Mount Buninyong. To an old colonist of the early days, the names of these townships, diggings, mountains, and rivers are very familiar: and to me, who has been absent for 24 years, this survey from an elevation of 2500 feet above sea level was very pleasant, revealing the wonderful development which had taken place. … We got back to Hugh Jones’s house by four o’clock, and were glad to partake of the good things prepared for us.

This phase began with the establishment of a road to the summit in 1884 and included improvements to the road in 1926 when a low platform lookout was built also constructed on the summit (Leather, 2008). In 1932 the Bell Memorial Tower (an old mine poppet head) was erected and replaced the platform lookout. The picnic rotunda was also built around this time (Leather 2008). A simple tower was built in 1916, replaced by a ‘poppet head’ from Bendigo in 1928 which was later returned to its original home when a third tower was erected in 1979. C.P. Wilson an engineer from Buninyong reported to the Buninyong Shire Council on November 1, 1928 that the “poppet heads for the look-out on Mount Buninyong had been erected at a cost of £296, but that a further expenditure of about £100 must he incurred before it could be opened” (The Argus, 2/11/1928). Wilson noted that £275 had been received towards the cost, and that the Ballarat City Council had promised a second contribution of £25, and the further £50 was expected from the Forest Commission (The Argus, 2/11/1928). The views are extensive from this high tourist vantage point, however this lookout was condemned unsafe and the present lookout was built in 1979, which still functions as a fire lookout tower (Thorpe & Akers 1982; DSE Heritage Database 1998). A concrete water tank for stock use was constructed in the crater area in the 1920s. Some of the land was cultivated for crops such as oats and potatoes. Ringlock fencing still remained in the Mount Buninyong Reserve from this period (City of Ballarat, 1997).

Mount Buninyong has a long history of passive recreation, perhaps best demonstrated by the succeeding look-out towers and the past tradition of New Year’s Day picnics (City of Ballarat, 1997). In the 1920s the Buninyong Progress Association requested a ten year lease to build a lodge on the summit. An associated request for a ‘good tourist road to the summit’ was approved but the lodge was not (City of Ballarat, 1997: 11). In the 1930s the Progress Association took on board a ‘beautification campaign’ designed to soften Mount Buninyong with exotic trees and bulbs. The colours of the planting remnants can still be seen on the Mount today (City of Ballarat, 1997).

In December 1937, Mrs R.D. Nevett, formerly Divisional Commissioner of the Girl Guides’ Association in Broken Hill, reflected on a recent visit to Mount Buninyong and her family’s association with the district. She commented on ‘vandalism’ at the site:

Flying between Mt. Warrenheip and Mt. Buningyong when approaching Ballarat, feeling of the deepest reverence surged through me as the sunlight caught the steel “look-out” erected on the summit of the latter mount as a memorial to my public-spirited father who, with other splendid pioneer citizens, made this lovely inland city with its main street named after Sturt, the explorer, and modelled on Princess-street, Edinburgh, with flower gardens, glorious trees, shrubs and statuary extending more than a mile down the centre. You can understand something of my pride after I had read in a record of my father’s life sent to us by the Legislative Council of Victoria, of which he was a member, that one of his last acts in the House was to urge that sufficient money be granted to construct a road to the summit of Mt Buninyong, thus serving a dual purpose–the relief of unemployment and the addition of another attraction for the tourist.

The grade of this one-way traffic road is a triumph for the engineer as it winds, very gradually round this mount, whose height is over 3000ft. Arriving at the summit one climbs the winding stairway to the “Look-out” and is rewarded by the splendid panorama that spreads on all sides. On clear days the waters of Corio Bay, Geelong, are discernible. This immense view is so fittingly symbolical of the great breadth of outlook and vision that my father undoubtedly possessed. When descending the stair way I was shocked to notice the work of wanton persons who had so thoughtlessly disfigured the steps and railings by cutting their names and initials thereon. Girl Guides let me give you an unwritten law-never defile any place by scratching or cutting your names anywhere. I have encountered this same vandalism at the Grampians, also at the Blue Mountains (Barrier Miner, 21/12/1937).

In January 1952 the shelter kiosk on the summit of Mount Buninyong was ‘burnt down by vandals’ (The Argus, 26/1/1952). In September 1954 the State Government announced that it was providing £940 for improvements to the Mount Buninyong and Lal Lal Falls reserves, providing the committees of management could find a one-to-four contribution. At Mount Buninyong the roadway around the mount was to be reconstructed, and tables and seats supplied in the reserve (The Argus, 27/9/1954). The mount was subject to vandalism in November 1955:

VANDALS CAUSE HAVOC AT MT. BUNINYONG

BALLARAT, Tuesday: Vandals have caused considerable damage to installations at Mt. Buninyong summit and Mt. Buninyong and Lal Lal reserves. Vandals are also blamed for the serious fire which swept through the area recently. Repeated acts of destruction have the reserves committee worried, chairman Mr. P. E. Selwyn Scott said today. In a tour of the area to day Mr. Scott pointed out damage caused by vandals. Hundreds of beautiful messmate trees are still blackened and bear the scars of the fire. Mr. Scott said one of the most serious effects of the fires was the killing of regrowth of timber. One side of the Mount was becoming bare. The fire in February destroyed the shingle roof of the rotunda on the summit. Vandals also unscrewed the tap of a 5,000-gallon water tank. They let all the water out, and took the tap. They also took the downpipe from the roof into the tank. A rock fireplace was smashed and an attempt made to cut down a guide post indicating the down route for motor traffic from the summit. Absence of this sign could result in a serious accident to motorists trying to descend the mountain by the wrong route and meeting the up traffic. The Cr. Alex Bell memorial sign has been wrenched from the side of the staircase to the tower. The temporary shelter for fire spotters has been thrown down. Most serious damage was the removal of a large bronze direction tablet on the top of the 75ft. high tower. It was broken into three pieces. Removal of this plate must have taken considerable effort, and it is thought a hacksaw was used. The safety fence around the platform at the top of the tower was pulled loose at two points (The Argus, 16/11/1955).

In the 1960s the road to the summit was sealed during a period of time when grazing leases were terminated, but at this time the Buninyong Shire Council permitted a telecommunications tower to be constructed on top of the Mount (DSE Heritage Database, 1998). The multifaceted tower is large and fenced with hurricane steel mesh and the buildings are of apricot brick, with many large satellite dishes (DSE Heritage Database, 1998). In 1985 a further meshed area of much smaller scale was permitted and contains a tower for police communication. In the late 1990s there was an application for a further tower to be built (DSE Heritage Database, 1998).

7.4 Fourth Phase: Duplication

‘Duplication’ is MacCannell’s fourth phase in the development of attractions when copies of the nucleus of the attraction, in this case the mountain, are made available through media such as paintings, photographs, and postcards. This phase is also known as ‘mechanical reproduction’ (MacCannell, 1999). The nucleus of the attraction is reproduced, in regards to Mount Buninyong duplicates are made through paintings and photographs.

The Mount has been associated with artist S.T. Gill who titled his sketch in the mid-1850s ‘Ballarat from Mt. Buninyong’ as well as Henry Winkles who in 1852 made a lithograph of the township of Buninyong which included the Mount in the foreground (Thorpe & Akers, 1988; Faulkner, n.d) (see Figs.7.2 & 7.3 & 7.4). Archibald Vincent Smith was a photographer who also took various photographs of the Mount in 1866 and Ballarat district (Trove, 2013).

7.5 Fifth Phase: Social Reproduction

For MacCannell, the final stage of sight sacralization is social reproduction which ‘occurs when groups, cities, and regions begin to name themselves after famous attractions’. In the case of Mount Buninyong, social reproduction has occurred in the naming of the Boninyong pastoral run, Buninyong township, Buninyong primary school, and businesses such as Mount Buninyong Winery. Many businesses in Buninyong have the name Buninyong as part of their business names.

7.6 Tourism at Mount Buninyong

In the 19th century, Mount Buninyong was a very popular scenic attraction. Walks ambled from the foothills up through the crater to the summit with a simple wooden lookout platform. Later additions to the attraction included a rotunda-styled shelter, toilets and barbecue facilities (Leather 2008). Succeeding generations climbed the Mount unaided by tracks and picnicked in the crater–notably on New Year’s Day (DSE Heritage Database, 1998).

The Reserve was recommended as a Scenic Reserve by the Land Conservation Council in 1982 (City of Ballarat, 1997). It is a popular destination for a drive out of Ballarat and is listed on local tourist brochures. It also offers a popular running and jogging track for fitness devotees (DSE Heritage Database, 1998). Mount Buninyong is much used by tourists, locals and visitors who enjoy the views from the tower of the summit and a walk in the beautiful surroundings. Snowfalls are a feature in winter. There are walking tracks and a road to the summit and down the other side. This area is a significant link with the Union Jack Reserve, north of Buninyong township, which is clothed in native scrub after mining activity in the 19th century (DSE Heritage Database, 1998).

Mount Buninyong Scenic Reserve offers an opportunity to experience a different bush land setting than is generally found in the region (City of Ballarat, 1997). The reserve has significant natural values. Its scoria cone carries an exclusive vegetation type of regional and state importance as one of the few scoria cones in Western Victoria which has retained native vegetation and provides spectacular views of the surrounding landscape (City of Ballarat, 1997).

In 1980 the present Mount Buninyong tower was opened to the attraction and in 1982 an information board and rotunda was constructed, and water tower was painted. Picnic seats and barbeques were put in place as were the formation of nature tracks and a new car park area was established (Leather, 2008).

In 1997, the City of Ballarat directed major recommendations for the Mount Buninyong Scenic Reserve including:

Biological surveys will be conducted to identify all significant flora and fauna.

– A vegetation management program will be introduced to restore understory species and to protect significant species and communities.

– Monitoring programs will be established to evaluate vegetation management techniques.

– Linkages will be developed from the reserve to nearby remnant vegetation.

– Fire management will be carried out using a permutation of slashing and the development of an ecological burning program for the reserve.

– New visitor facilities will be developed at the entrance to the Reserve and will include orientation information for the Reserve and its adjoining linkages. Existing visitor facilities will be rationalised.

– The existing walking track system will be upgraded and improved to enable return loop walking opportunities.

– The Mount Buninyong Access Road will be managed to ensure visitor safety

– Visitor enjoyment will be enhanced by the provision of interpretation of the Reserve’s natural and cultural features as well as those of the surrounding region.

– Community awareness and involvement.

– Investigate and document Aboriginal history and protect identified sites as appropriate, in consultation with the local Aboriginal community.

– Involve the local Aboriginal community in developing interpretation for the Reserve and environs which relates to Aboriginal cultural heritage.

– Remove ring lock fencing from the reserve.

7.7 Conclusion

As a tourist attraction, Mount Buninyong–with its natural and cultural values, has transitioned from being an attraction for farming purposes in colonial days and a scenic attraction for picnics to being a highly recognizable public reserve (City of Ballarat, 1998). This paper has attempted to explain this transition by showing the significance of the works provided by MacCannell, Butler and Gunn. This paper demonstrated that when these works are combined they contain explanatory materials in comprehending the history and evolution of a natural and cultural tourism attraction.

Mount Buninyong is an important site for the acknowledgment of the ongoing connection of Aboriginal people with the land through creation stories and cultural sites and is an ideal site for interpreting Aboriginal cultural history (City of Ballarat, 1997). The Australian Heritage Commission has stated that it is possible that Aboriginal cultural values of national estate significance may exist for the Mount. This statement of significance is for a place with natural significance from a scientific and interpretive perspective as well as from a geological and geomorphic perspective. For this place the cultural values are more significant and are historic as well as social.

Mount Buninyong is an area of high geological and geomorphological significance. It is an excellent example of an amalgamated volcano; that is, as the Department of the Environment and Heritage (2003) describes as one which has both a breached scoria cone and associated lava flows. The place also provides a good illustration of the varied topography that has developed on adjacent lava flows of differing ages. In addition, it is a good example of the effects of aspect on plant communities (Department of the Environment and Heritage, 2003). Mount Buninyong has excellent interpretive value as it is the most obvious example in Victoria of a breached scoria cone and associated lava flows. The site is easily accessible as it is the only major scoria cone with a deep crater that remains on public land in Victoria (Department of the Environment and Heritage, 2003). The Mount is still used as a scenic attraction today, the bond between the local community and Mount Buninyong has always been strong. This has been expressed through organized interest groups as well as in the varied recreational pursuits of individual residents. In relation to Butler’s life cycle model, the Mount could be said to be at the ‘rejuvenation’ stage as it is continuously being maintained and upgraded. In early 2012, the Ballarat Courier undertook a survey of the Ballarat region’s favourite natural attraction. Lal Lal Falls was considered the region’s best, securing 37.5 per cent of the vote; Lake Wendouree came in second with 32.3 per cent, and Mt. Buninyong, third, with 9.4 per cent (Ballarat Courier, 8/2/2012).

References

Australia. Department of Environment and Heritage. (2003) Protecting National Heritage (2nd ed). Canberra: Australian Heritage Commission.

Australia. Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. (1998) Australian Heritage Database. Canberra, Australia. Retrieved 3 November 2012 from http://www.environment.gov.au/cgibin/ahdb/search.pl?mode=place_detail;place_id=100370

Beggs-Sunter, A. (2005). Eureka–The Buninyong Connection. Buninyong: Ballarat Reform League. Retrieved 10 December 2012 from http://www.ballaratreformleague.org.au/buninyong.htm

Blake, L.B.J. (1977). Place Names of Victoria. Adelaide: Rigby Ltd.

Bride, T.F. (Ed.) (1898). Letters from Victorian pioneers: being a series of papers on the early occupation of the colony, the aborigines, etc. Melbourne: RS Brain.

Butler, R.W. (1980). The Concept of a Tourist Area Cycle of Evolution: Implications for Management of Resources. Canadian Geographer, 24:5-12.

City of Ballarat. (1997). Centre for Environmental Management. Mount Buninyong Scenic Reserve Final Management Plan. Retrieved 12 December 2012 from www.ballarat.vic.gov.au/.../mt%20buninyong%20scenic%20reserve

City of Ballarat. (2012). Mt Buninyong Scenic Reserve. Retrieved from http://www.ballarat.vic.gov.au/lakes-parks-recreation/nature-reserves/mt-buninyong-scenic-reserve.aspx

Clark, I.D. (ed.) (2000). The Journals of George Augustus Robinson, Chief Protector, Port Phillip Aboriginal Protectorate, Volume One: 1 January 1839-30 September 1840. Clarendon: Heritage Matters.

Clark, I.D. (2002). The ebb and flow of tourism at Lal Lal Falls, Victoria, a tourism history of a sacred Aboriginal site. Australian Aboriginal Studies, 2:45-53.

Clark, I.D. (2009). Naming Sites: Names as management tools in indigenous tourism sites -An Australian Case Study. Tourism Management, 30:109-111.

Clark, I.D. & Heydon, T.G. (2002). Database of Aboriginal Placenames of Victoria. Melbourne: Victorian Aboriginal Corporation for Languages.

Faulkner, S. (n.d.) Brim Brim Gardens. Retrieved 12 December 2012 from http://www.brimbrimgardens.com.au/history.htm#bun

Geocaching. (2008). Mount Buninyong Crater. Retrieved 12 December 2012 from http://www.geocaching.com/seek/cache_details.aspx?guid=e255a4e8-facf-4624-b9f1-23c7ed523074

Griffiths, P.M. (1988). Three Times Blest: A History of Buninyong and District 1837-1901. Buninyong: Buninyong & District Historical Society.

Gunn, C.A. (1994). Tourism Planning Basics, Concepts, Cases. Washington: Taylor & Francis.

Gunn, C., & Var, T. (2002) Tourism Planning Basics, Concepts, Cases. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Hercus, L.A. (1999). Place Names Notes and Papers relating to the Place Names Dictionary Project, Victorian Aboriginal Corporation for Languages, Melbourne.

Hughes, J. (1891). Australia Revisited in 1890, and Excursions in Egypt, Tasmania, and New Zealand. Being extracts from the diary of a trip around the world, including original observations on colonial subjects and statistical information on pastoral, agricultural, horticultural, and mining industries of the colonies. London: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co.

Kirkland, K. (1845). Life in the Bush. By a Lady. Chambers’s miscellany of useful and entertaining tracts, William and Robert Chambers, London, 1(8):1-39.

Leather, D. (2008). Buninyong: Mount Buninyong. Retrieved 11 December 2012 from http://www.buninyong.vic.au/mount.htm

Leathes, E.D. (1880). An Actor Abroad: Or, Gossip Dramatic, Narrative and Descriptive, from the Recollections of an Actor in Australia, New Zealand, The Sandwich Islands, California, Nevada, Central America, and New York. London: Hurst and Blackett.

MacCannell, D. (1976). The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class. New York: Schoken.

MacCannell, D. (1999). The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class (Revised edition). California: University of California Press.

MacCannell, D. (2001). Sight Seeing and Social Structure. In S.L. Roberson (Ed.), Defining Travel: Diverse Visions (pp. 13-29). Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi.

Macqueen, A. (2010). Frederick Robert D’Arcy: colonial surveyor, explorer and artist c1809-1875. N.S.W: The Author.

Massola, A. (1962). Two Aboriginal Legends of the Ballarat District. Victorian Naturalist, 79(4):110-111.

Smyth, R.B. (1878). The Aborigines of Victoria, 2 vols. Melbourne: Victorian Government Printer.

Stanbridge, W.E. (1861). Some Particulars of the General Characteristics, Astronomy, and Mythology of the Tribes in the Central Part of Victoria, South Australia. Transactions of the Ethnological Society of London, 1:286-304.

The Argus 22/1/1877; 2/11/1928; 26/1/1952; 27/9/1954; 16/11/1955.

Thorpe, M.W. & Akers, M. (1982). An Illustrated History of Buninyong. Buninyong: Buninyong & District Historical Society.

Trove. (2013) The Crater of Mount Buninyong. Retrieved 13 January 2013 from http://trove.nla.gov.au/work/12516621?q=creator%3A%22Smith%2C+Archibald+Vincent%2C+1837-1874%2C+%28ph otographer.%29%22&c=picture&versionId=14787987

Withers, W.B. (1887). The history of Ballarat, from the first pastoral settlement to the present time (2nd ed.). Ballarat: F.W. Niven & Co.

Fig. 7.1: Untitled drawing showing Mt Buninyong by J.B. Henderson, c. 1853-1856. State Library of Victoria Pictures Collection, Accession No. H28122.

Depicts two lines of huts at the base of Mt. Buninyong.

Fig. 7.2: The township of Buninyong, Victoria drawn & engraved by H. Winkles. Engraving 1855. (In private collection of Ian Clark)

Fig. 7.3: ‘Buninyong Hill’. Wood engraving The Illustrated London News 29 May 1852.

Fig. 7.4: ‘Mount Buninyong, Near Ballaarat’. Wood engraving by George Stafford 1861, reproduced in The Illustrated Melbourne Post, April 1862, George Slater, Melbourne. State Library of Victoria Pictures Collection.