5 Den of Nargun, Mitchell River National Park by Sharnee Sergi and Ian D. Clark

This chapter is concerned to document the history of the development of the Den of Nargun as a tourism site utilising the theoretical constructs developed by MacCannell (1976), Butler (1980) and Gunn (1994). These perspectives provide insights into the historical maturation of a cultural or natural site into a tourism attraction. MacCannell’s (1976) perspective reflects progressive development of attractions over five phases – naming, framing and elevation, enshrinement and duplication, and social reproduction. For the purpose of this study, Butler’s (1980) ‘tourism area life cycle model’ will be correlated with MacCannell’s model of the evolution of attractions in order to navigate the development and tourism history of the Den of Nargun. Furthermore, utilisation of Gunn’s (1994) spatial model helps to provide an understanding of the contextual and environmental development and character of the site.

The Den of Nargun is an important geological and Aboriginal cultural site located in the Mitchell River National Park in East Gippsland and is situated approximately 50km northwest of Bairnsdale, Victoria. The evolution of the Den of Nargun as a tourism attraction is contextualised with the Mitchell River National Park’s own history and will be, in part, explored in this study. The Mitchell River National Park and the Den of Nargun, as it is known today, was formally known as the Glenaladale National Park (Catrice, 1996). References to the Den of Nargun are commonly cited in older works as being a part of the Glenaladale National Park. For clarity, this study will refer to the Den of Nargun as being a part of the Mitchell River National Park and will signpost the transition from Glenaladale National Park to Mitchell River National Park. Currently, the Mitchell River National Park is approximately 12,000 hectares in size and is a part of a larger ecosystem which extends across Victoria from the Great Dividing Range and continues down to the Gippsland Lakes (Parks Victoria, 1998; Parks Victoria, 2011). The Mitchell River itself is listed as a heritage river, being Victoria’s largest ‘free flowing’ river. The river extends down the centre of the National Park dividing the park into two sections, the east and west. The east side of the Mitchell River National Park has been widely developed for tourism enjoyment, whilst the west side remains largely untouched (Parks Victoria, 2011).

The Den of Nargun is situated along Woolshed Creek approximately 1.5 kilometres from the Mitchell River Gorge (Department of Environment and Primary Industries, 2012) (see Fig.5.1). It is set amongst warm temperate and dry temperate rainforest (Australian Government, 2011). It is believed that the cave was formed approximately 360 million years ago (Harvey, 2007). The natural occurring geological formation of the cave was shaped as a result of eroding mudstone developing beneath highly resistive sandstone. For this type of conglomerate cavern formation, the Den of Nargun is documented as the largest on record in Australia. Large stalactites are present at the entrance of the tunnel with small stalactites formed on the inner surface of the cave. At the exterior of the cave, there is a small waterfall that runs over and down the front of the cavern entrance into a plunge pool created and serviced by Woolshed Creek (Australian Heritage Place Inventory, N.D.; Department of Environment and Primary Industries, 2012; Harvey, 2007).

Situated on the boundary between Brabralung and Brayakaulung Aboriginal country which is part of the Gunaikurnai ‘nation’, the Den of Nargun is of cultural significance to the local Aboriginal community (Australian Government, 2011). The Indigenous significance of caves in Victoria is noted by Clark (2007: 7) who notes that ‘caves were often thought to be the abode of malevolent creatures and spirits’ including the mythical creatures inhabiting Gippsland, the Nargun and the Nyol. The Den of Nargun is home to the mythical creature, Narguna who is described as being a ‘fearsome creature with human arms, hands and breasts, otherwise made of stone’ (Calder, 1990). Etheridge (1893: 130) has commented on this ‘well known dread of caves exhibited by the Aborigines, a dread even handed down to the half-castes. Unless under very exceptional circumstances few Australian blacks can be induced to enter one of these places’. He referred to the example provided from Howitt: ‘Again, our leading authority on all matters aboriginal, Mr. A.W. Howitt, in describing his exploration of the Mitchell River, in North Gippsland, mentions the ‘wonderment of his sable companions, Turnmile and Bungil-Bottle, at the stalactite caverns on Deadcock Creek, regarded by them as the haunt of the mysterious creature’, the ‘nargun,’ the ‘nargun a narguna’, or ‘den of the nargun’ (Etheridge, 1893: 130).

It is believed that the Brayakaulung tribe who lived on the western side of the Mitchell River and Brabralung tribe who inhabited the eastern side of the Mitchell River had been visiting and utilising the Den of Nargun for 5000 years (Harvey, 2007). The Den of Nargun is of particular importance to Indigenous women and it is said to be a site where women’s ‘initiation and learning ceremonies’ occurred (Australian Government, 2011; Australian Heritage Place Inventory, N.D, para. 7; Harvey, 2007). It is also believed that Indigenous men from the local tribes will not visit the Den of Nargun as it is a sacred place for Indigenous women only (Environment Victoria, N.D.).

In terms of European land tenure, the Den of Nargun site formed part of the Glenaladale pastoral run, some 20,480 acres first taken up in October 1845 by the McLean brothers and Simon Gillies (Billis & Kenyon, 1974: 211). In July 1866 the run was subdivided into Glenaladale and Mharlooh: the former was licensed to J.H. Clough and J.W. Bogg, and the latter to Simon Gillies.

5.1 First Phase: Sight Sacralization and Naming 1875–1919

MacCannell’s (1976) theory of sight sacralization identifies the first phase of attraction development as the ‘naming stage’. This refers to the initial notions of naming a site and forming the final site name. Prior to the appointment of the placename, steps are usually taken to investigate attributes, features and historical poise (MacCannell, 1976). In this instance the site was specified the name ‘Den of Nargun’ and the nucleus is the cave itself. The aesthetic and cultural value of the nucleus and the supernatural presence of the Nargun believed to be living in the cave would motivate both environmental and cultural visitation in years to come.

It is believed that the first European to visit and record information about the ‘Den of Nargun’ was Bairnsdale-based goldfields warden Alfred William Howitt in January 1875 who ‘found’ the site during a search of the Mitchell River (Howitt, 1875). He was accompanied by two Brabralung Aboriginal guides Bunjil-Bottle aka Charley Boy and Master Turnmile aka Long Harry. Howitt published the following account of his visit to the site:

After slowly picking my way along the rocky floor of the creek for perhaps a mile, admiring the beauty of the scene, and occasionally drinking from the rock pools of “nice cool la-en yarn” (water), as Tunmile phrased it, we came to a picturesque cavern, formed by the wearing away of the soft beds from underneath a hard course of grit. It extended in a semicircular form across the creek, the roof of the cave being the ledge over which the water falls during rainy times. The blackfellows were delighted with this “house,” and planned to themselves how they could come and camp here and collect the tails of the “woorayl” (lyre bird) among the scrubs of the river, and feast on the native bears and wallabies, poor unsuspecting creatures of the neighborhood.

Here we had to climb up the cliff at the side by a wallaby track to get out, but being once again in the creek bed there were the same pleasant shades as before. A little further on we came to a second cave, a wonderfully picturesque and beautiful spot. As before, a soft bed of reddish shale had been worn away by the backwash of waters falling over a hard ledge, but here the cave was higher and deeper. In front was a pool of water looking black and smooth as glass under the dense shade of the “Lilly pillys” (Acmenia). Stalactites fringed the rim of the cavern and hung in pendent rows from its roof. A huge stalactitic mass at one side joined the roof to the floor so as partly to screen the cavern, and on either hand the rocks rose up almost perpendicularly for I think not less than 400 to 500 feet.

Two lyre-birds which were disporting themselves in the cavern almost delayed their departure too long. Bungil Bottle narrowly missed one with a lump of wood which he threw as quick as lightning, and Master Turnmile, being very excited, was in the act of throwing my new tomahawk at the other among the rocks when I stopped him. I preferred my new tomahawk to a dead lyrebird, but my aboriginal seemed not to see it in the same light.

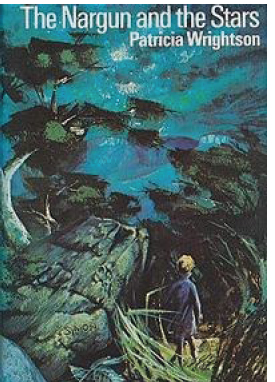

While I made a slight sketch (No. 21) [see Fig.5.2] and examined the rocks, the two blackfellows looked round the cave with many wondering exclamations of “Ko-ki” at the stalactites, two of which they carried off as wonderful objects to show their friends. I was amused listening to them conversing in the mouth of the cavern. Master Turnmile, “the dandy,” thought it would be a splendid place to run off to with one of the aboriginal young damsels–a house ready provided, plenty of wallabies and native bears, and a country unknown to the other blackfellows. Bungil Bottle on his part was impressed vividly by the belief that this was indeed the haunt of the mysterious creature, the “nargun,” the “ngrung a narguna” (Den of the Nargun).

The nargun, according to their belief, is a mysterious creature, a cave-dweller, which haunts various places of the bush. So far as I could learn, the blacks believe the nargun haunts especially the Mitchell valley, which we had just followed from Tabberabbera. What is the appearance of a nargun they cannot describe, excepting that it is like a rock (wallung), and is said to be all stone except the breast and the arms and bands. They say it inhabits caverns, into which it drags unwary passers-by. If you throw a spear or fire at it with a bullet, they say the spear or ballet will turn back on you and wound you. There is a cave in the Miocene limestones of Lake Tyers which is said to be inhabited by a nargun, with which one of the natives, “Dan’s mother,” according to report, had a fight. This is all I could learn.

The rocks at the “nargun’s cave” I found to be the usual alternations of sandstones and grits with pebble conglomerates, and here, as in the typical locality near Iguana Creek, were thick beds of soft reddish rock, apparently devoid of stratification and evidently calcareous, judging from the stalactites which depended from the roofs and sides.

From the “ngrung a narguna,” we found it no easy matter to escape. The ledge which formed the roof was some 30 feet above where we stood, and overhung the deep pool, except in one corner, at which a narrow ledge gave entrance to the cavern. The rocks on either hand rose up almost perpendicularly, far up above the tops of the trees in jutting sandstone ledges. The only plan seemed to be to go back down the creek and climb up the mountain sides. At last I got the two blackfellows to fall a tall straight young tree, and after much struggling we got it reared up at the corner of the roof. Bungil Bottle cut foot notches with his tomahawk and ascended as easily as going up stairs. I followed without my boots, and long before I had walked up the notches of these 30 feet of height, heartily wished, for once, that my feet had been as hard and horny in the soles as those of my black attendants.

The roof of the cavern was another succession of sandstone beds, nearly horizontal, and forming as it were broad steps up the creek. But the trees were now not so high, and the sides of the glen widened out into a gully. The heat and smoke were excessive after coming from among the cool shades below (Howitt, 1975: 219-221).

In correspondence with his father, William Howitt, Alfred Howitt, noted what his Aboriginal companions said about this location (Howitt, 1971: 200):

The blacks said it must be the home of the ‘Yabbung’, a mysterious creature which they believe haunts these mountains where they were living in caves and holes and preying upon the blacks when it can catch them. If you fire at it they say the bullet will turn round and wound you – or the spear thrown will turn back and pierce the thrower. The name of this cave is therefore ‘Bunga Yabbunga’ or the ‘Yabbung’s Home’ …

Mary Howitt (1971: 200) noted that Bunga Yabbunga is now called the Den of Nargun and is a popular picnic place for sightseers. Howitt’s account of his visit to the Den of Nargun was published in the Geological Survey of Victoria in 1875, along with a drawing of the site (see Fig.5.2).

Calder (1990: 207, 209) discusses Howitt’s journey to the Den of Nargun:

Howitt had come down the river from Tabberabbera in bark canoes built by the two Aborigines who accompanied him. The rapids in the Mitchell proved too much for them, however, and they abandoned the canoes and continued overland, striking up Woolshed (Deadcock) creek where they soon came across the Den of Nargun. This valley forms an impressive contrast the surrounding country at any time, but it must have been particularly dramatic on that day, as bushfires were raging amid the dry country above them while they, and large numbers of frightened birds and animals, remained protected in the valley below. The den formed an apparently total block to further progress, but the Aborigines soon felled a tree so that it leant against the overhang of the cave. They then cut steps in the tree, and all were able to proceed. Meanwhile, Howitt busied himself with ‘a slight sketch of’ ‘this wonderful picturesque and beautiful spot’.

It is documented that the Aboriginal name for the site was recorded as ‘Ngrung a Narguna’. Howitt recorded the site name as it was spoken to him from the Indigenous guides. They described ‘Narguna’ as being fierce “half flesh and half stone [being] who could kill unwary people through the strength of their embrace” (Australian Government, 2011, para. 4).

In Gippsland, caves are associated with two mythical beings; the Nargun and the Nyol. In 1875, Alfred William Howitt explored the Mitchell River by canoe accompanied by two Ganai men–Turnmile and Bunjil Bottle (Seddon, 1989). Up one creek, known as Deadcock Creek, they came to a cavern now known as “Den of Nargun” [3GP-5]. Howitt noted that his companions expressed delight upon finding this cavern, and planned to return and camp there and collect the tails of the woorayl (lyrebird) among the scrubs of the river, and feast on koalas and wallabies. A little further on, they came to a second cave, fringed by stalactites. The two Ganai men removed some stalactites to show their friends. Bunjil Bottle was convinced that this was the haunt of the mysterious creature, the Nargun, the ‘Ngrung a Narguna’ (Seddon, 1989: 18). Howitt’s companions could not describe a Nargun, beyond that it is like a rock (wallung), and is said to be all stone except the breast and arms and hands. It inhabits caverns, into which it drags unsuspecting passers-by. Howitt knew of another cave in the Miocene limestones of Lake Tyers that was said to be inhabited by a Nargun (Seddon, 1989: 18). Massola (1962) searched for this cave and found that its description matched not the presently named “Nargun’s Cave” [3NN-1] but another cave, “Cameroon’s No.2” [3NN-3] (Clark, 2007: 8).

R. Brough Smyth (1878 Vol. 1: 456-7) published the following entry on ‘Nrung-ANarguna’:

A mysterious creature, Nargun–a cave-dweller–inhabits various places in the bush. He haunts especially the valley of the Mitchell in Gippsland. He has many caves; and if any blackfellow incautiously approaches one of these, that blackfellow is dragged into the cave by Nargun, and he is seen no more. If a blackfellow throws a spear at Nargun, the spear returns to the thrower and wounds him. Nargun cannot be killed by any blackfellow. There is a cave at Lake Tyers where Nargun dwells, and it is not safe for any black to go near it. Nargun would surely destroy him. A native woman once fought with Nargun at this cave, but nobody knows how the battle ended. Nargun is like a rock (Wallung), and is all of stone except the breast and the arms and the hands. No one knows exactly what he is like. Nargun is always on the lookout for blackfellows, and many have been dragged into his caves. He is a terror to the natives of Gippsland. How Bungil Bottle behaved when he came in sight of a cave at Deadcock Creek in Gippsland, and what kind of a being Nargun is, and where he dwells, and how he behaves, are well told by Mr. Alfred Howitt.

Aldo Massola (1969), an anthropologist who conducted research into Aboriginal sites in Victoria abbreviates ‘Ngrung a Narguna’ to ‘Nargun’. Massola (1969: 191) details his conversation with the local Indigenous people of Lake Tyers who describes the Nargun as:

Those half human and half animal beings who lurk in deep underground recesses and who occasionally call out Nga-a-a-a. They are feared exceedingly, for they eat blackfellows, and their stone bodies have the power to turn spear or bullet back on the thrower, so they cannot be killed. The legend of the Nargun, was also said to exist at Lake Tyers at a place called the Devils hole or Ngrung. However, according to the Aboriginal legend, The Nargun was “vanquished by Lilly” who was “the only person to ever beat the Nargun”. Later, Lilly fell into Lake Mystery and her body was taken by a Bunyip (Massola, 1969: 191).24

During the immediate years following Howitt’s ‘discovery’ of the Den of Nargun in 1875, there is little known about any tourist or visitor activity. As described in Howitt’s account, given the harsh and dense terrain that needed to be trekked in order to get to the Den of Nargun, it can be suggested that there was little tourism activity during this time (Harvey, 2007). The next account of visitation is revealed by the Bairnsdale Advertiser and Tambo and Omeo Chronicle (26/1/1884) in an article entitled ‘How I found the Nargun’s cave’ by a local land selector named J.D.S. The newspaper editorialised the article, noting that ‘We believe it is not generally known that there is such a cave in this district, but it is near Lake Tyers. One of the myths of the aborigines is ‘Ngrung-a-Nargun”. The superstition is that a monster known as “Nargun” dwells in a cave, and though it cannot be killed by the blacks, it will kill and eat any black who approaches near the cave. It is believed that if any one throws a spear at “Nargun” the spear will return and wound the thrower. The cave referred to at Lake Tyers has always been regarded with dread by the blacks’.

HOW I FOUND NARGUN CAVE. (By J.D.S.)

When first I came to my selection, now some years ago, the blackfellows used to tell me, “Nargun will eat you.” Thinking it was only their way of joking I took no notice of what they said, but when I became better acquainted with them, some of them very seriously told me, Nargun, has a cave near you and will be sure to find you out some day. One of the more intelligent of them informed me that this was a monster like a woman, but much larger, very strong, and covered with scales like a fish, that she had a great taste for eating blackfellows, and if one of them came near her cave he never got away, but was sure to be devoured. I find in Mr. Brough Smyth’s interesting book about the aborigines that he mentions among their myths this of Nargun, and, that this being is supposed to live in a cave near Lake Tyers. These various statements made me wishful to discover, if possible, the residence of so formidable a neighbor. Mr. Bulmer informed me that he had seen the cave, but it was so many years ago that he had forgotten the precise locality. I often tried to induce the blackfellows to show me where it was but could not succeed; they positively declined to be eaten. I was too busy with work on my selection to give time for exploring, but sometimes on a holiday would search the gullies in the direction of the mysterious cave, though hitherto without success. Last week two young men, who were rusticating in this neighborhood, one a school master, who, tired of teaching the young how to shoot, for a change came to shoot wallabies; the other a candlemaker, came to my selection to recreate. One day was set apart for trying to find Nargun cave. We made an early start, and after pushing our way through some very rough country, came to a large gully that I thought was somewhere about the place I wished to find.

Proceeding down it for about half a mile we came to where some rocks had fallen, and half hidden by ferns and bushes was the entrance to the cave. We scrambled over the rocks and found an opening high enough for us to stand in upright. The roof came lower, and we had to stoop, then crawl on hands and knees, and our progress was neither rapid nor pleasant. We soon got tired of it, and reaching our candle as far as possible, could see no change for the better, so we backed out, and were not sorry to get into daylight again. We unanimously resolved that if this is the famous Nargun cave it is not worth coming to see. I suggested that instead of returning the way we came we should keep down the gully and follow the creek towards home as the scenery was very beautiful. All were willing, so away we went, the school master leading. Very soon he let a great shout out of him, “Why, we have not been in the cave at all, here it is.” And sure enough the gully had come to an abrupt end; a spur of the range had cut across it, and in the face was a large rent or crack some twenty or thirty feet high, and just wide enough for a person to walk in. It was a wild looking place, and made us think of those lines in the “Fairie Queen,”

Ere long they come where that same wicked wight

His dwelling has, low in a hollow cave,

Far underneath a craggy, cliffy pight.

Dark, doleful, dreary, like a greedy grave.

That still for carrion carcases doth crave;

On top whereof aye dwelt the gastly owl,

Shrieking his baleful note, which ever drave

Far from that hunt all other cheerful fowl,

And all about it wand’ring ghosts did wail and howl,

And all about old stocks and stubs of trees.25

Spenser might have been here when he wrote this, for we have the cave, the owl, (the candlemaker shot it though) old stocks and stubs of trees, but where is Nargun? Our candle had got very short through exploring the first cave, so we had not much time to give to this. For about four hundred yards it continues narrow, and then opens out wide, and is much higher, perhaps forty to fifty feet high, but when we got this far our light was nearly gone, and much to our regret we had to return. A creek flows through the cave, but is dry at present. The drift wood shows that sometimes it is four or five foot deep. The mystery of the cave has yet to be explored, how far it goes, where is its outlet, where did Nargun cook the blackfellows, and other interesting particulars remain to be discovered. If some of our enterprising summer visitors solve these problems, well and good, if not, should we live to see another holiday, we may try again.

Julian Thomas, aka ‘The Vagabond’, paid a visit to the Lake Tyers district in April 1886, and his account of his visit reveals the identity of LDS and also adds to our knowledge of the Den of Nargun:

Mr Stocks, however, has not long been a farmer. He is an old Ballarat man, but has taken up this selection on the eastern shore of Lake Tyers as a haven of rest. There are patches of good black soil, and fruit grows well here, but the cost of clearing is very great. The Lancashire man, however, appears happy, and it is a pleasure to me to meet him, and have a talk about Old England. I am also highly interested in the description of the cave situated a mile from hence. The head waters of this lake have now become but a narrow stream known as the N’grung Creek. The cave is situated on its banks, and runs right through the limestone cliff, being more than a quarter of a mile long. A stream of pure water flows through the cave into the creek. In places it is 30ft high, and sometimes one walks through the narrowest of passages, at others the cave spreads out into wide chambers. One thinks that this would have been a magnificent place for the retreat of any outlaws or for blackfellows to camp and make their homes in. But the natives will not go near it. They dread this cave as much as the inhabitants of Tanna do the vicinity of the volcano of Yasur.26 The latter, however, have reason, for the hidden fires there have caused earthquakes which have wrecked the country, and the perpetual eruptions and streams of burning lava are sufficient to scare even white people. But the Gipps Land natives are frightened by a tradition of a demon who inhabited “Nargun’s Cave.” An evil spirit more powerful than all the m’raajti, a gigantic “thing” in female form, covered with scales, which is possessed with a strange taste in that it eats blackfellows. Nargun or Naguna is the title of this Lamia.27 So not even the Christian natives of the mission will go near the cave. The foundation for this story may have been the presence of a large seal in the cavern, or from the mists of the past the legend may have descended of some monstrous creature of the prehistoric order of animal life which might have survived here. But why, I ask myself, do so many races of men embody their horrible monsters in a female form? I give it up (The Argus 3/4/1886).

Furthermore, in circa 1900, but definitely prior to 1904, the Den of Nargun was visited by two brothers known as the ‘Morrison Brothers’ who discovered the cave by chance whilst droving cattle. The two men were from Glenaladale approximately 20 kilometres from the Den of Nargun (Google Maps, 2013, Catrice, 1996). In 1904 the Morrison Brothers returned to the site with psychologist and educationist, Professor Stanley Porteus (Catrice, 1996). Porteus (1951: 271) discussed the Den of Nargun in his novel Providence Ponds: a novel of early Australia, which is based on his wife’s forebears’ experiences in settling in Gippsland, and which explored the psychological effect of human isolation:

The cave of the Nargun has become one of my favoured refuges when any perplexities visit me. It is throughout the day a happy spot, just Australian bush, nothing grand or wonderful, merely a pleasant place, alive with the tinkle of bell-birds, small waterfalls, and glistening rock slides. I have no words for its beauty….

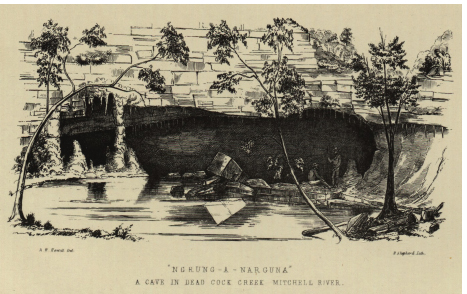

An historical photograph published by Department of Environment and Primary Industries (2010) captures a shooting party at the foot of the Den of Nargun in 1905 (see Fig.5.3). This provides some indication of visitation occurring during this era.

Exposure of the Den of Nargun increased as the years grew closer to the 1920s. This signals the transition of the tourist site into the second phase of tourism development. On 16 June 1917, The Weekly Times newspaper published an article entitled Off the Beaten Track- Visit to ‘Home of Evil Spirit’ by “All Round”. This article demonstrates the increased exposure of the Den of Nargun:

Legends of the “Ngrung-a-Narguna,” or home of the “Nargun,” an evil spirit of the blackfellow, reached certain members of the Melbourne Walking and Touring Club, who had also read Dr Howitt’s account of a visit he paid to it…This member writes:–It is over 40 years since Dr Howitt made a trip down the Mitchell River in bark canoes with two aboriginals. After two days voyaging down the upper reaches, through mountainous gorges and over rocky rapids, they came to the mouth of the Dead-cock creek, now known to the man-makers (but to no one else) as the Woolshed…

A LONELY FARM HOUSE.

A ten-day moon prevented the dusk from developing into dark, and so we walked along the bridle track round the hillsides and over the spurs till we came to the lonely farmer’s home within a mile of our objective. The family had gone to a patriotic concert five miles away, and would not reach home till daybreak, sleepy and with tired feet, but ready for another dance the following night if they had the chance. With characteristic bush hospitality, they placed their larder at our disposal so we boiled, our billy at their fire and cooked some saveloys for tea.

An hour later we were carrying our swags, a borrowed axe, and lantern, down a precipitous spur leading to the mouth of the Dead-cock creek. A few hundred yards up stream, we came to a pool surrounded by a natural amphitheatre sixty feet across, and floored with the flat sandstone rocks of the district. Up-stream, the water pouring over 20ft. of cliff kept the pool replenished and on the left hand the rocks rose sheer to a height of 120ft or more. Still higher could be seen the eucalypts of the bush above, with an occasional “currajong” perched on the edge of the cliff. For sixty yards along the right hand side a huge cavern extended 20ft. or more into the side of the hill, with a ceiling formed of another almost level layer of the same sandstone as formed the floor. Here we camped for the night in a little pool of bone-dry sand. The only exit from this amphitheatre was by a narrow wombat track which wound its precarious way back and over the roof to the cave until it reached once more the almost flat bed of the creek higher up. More rocky pools, more luxuriant vegetation of an Eastern Gippsland type led to another pool, waterfall and cavern. The gorge was narrower here, and the cliffs on either side were not only unclimbable, but rose sheer to a skyline fringed with currajong and stringy barks, two or three hundred feet above. This cavern, screened with stalactites and stalagmites, was the Ngrong-a-Narguna. Here dwelt the Nargun, an evil spirit whose lower half had turned to stone, and who stretched out a long arm and captured the unwary picanninie passing by.

The sketch made by Dr Howitt, and published in a Mines Department report in 1876 [sic], shows that little change has taken place except that one stalagmite has grown about 3ft. towards the roof of the cavern, and that a kanooka on the edge of the pool has increased from apparently about nine inches to over three feet in diameter.28 Nothing short of a ladder could have got us past the fall…

The earliest name for this site appears to be ‘Bunga Yabbunga’ meaning ‘Yabbung’s home’ sourced from correspondence between Alfred William Howitt and his father (Howitt, 1971: 200); another early name is ‘Ngrung a Narguna’ meaning ‘home of the Narguna, the stone-devil’. It is possible that Bunga Yabbunga is a mishearing of Ngrung a Narguna. ‘Nargun Cave’ is recorded in 1884; ‘Nargun’s Cave’ in 1886; ‘Cave of the Nargun’ in 1951. Today the site is known popularly as the ‘Den of Nargun’.

5.2 Second Phase: Framing and Elevation 1920–1985

MacCannell (1976) describes the second phase in the development of an attraction as ‘framing and elevation’. This refers to the deliberate attempt to increase exposure of a site or product through opening the site for tourist exploration or enhancing visual appeal. During this stage, the nucleus or site is framed through both protection and enhancement. Protection refers to safe-guarding the authentic value of the site or object and enhancement occurs when the object is enshrined. The second stage following the typology life cycle presented by Butler (1980) is the ‘involvement stage’. In this stage according to Butler (1980) tourism marketing plans begin to develop including the initial development plans with a foreseen increase in tourism numbers.

Historical records show that tourism to the Den of Nargun increased from the 1920s, with a large influx of visitors in the 1930s (Catrice, 1996). The increase in visitor numbers was the result of the increased exposure to the existence of the Indigenous site. An earlier visitor, Porteus who initially visited in 1904 with the Morrison Brothers returned to the site in 1923 accompanied by Robert Henderson Croll, a leading member of the Melbourne Walking Club who documented and published the Den of Nargun and its location in his guidebooks (Catrice, 1996). The walking club in 1923 was the first to call for the permanent reservation of the Mitchell River on ‘account of the splendid specimens of various indigenous trees’. Wheeler (1991: 37) suggests that Croll foretold the gazetting of the Den of Nargun as Glenaladale National Park when, on wandering through its shaded gorges in 1923, he declared it ‘a remarkable place – a museum of living trees of great age. It should be preserved as a national asset’.

Croll’s newspaper articles that were later published as The Open Road in Victoria (1928) and Along the Track (1930) opened the site for tourist exploration, starting a ‘hiking craze’ (Catrice, 1996: 2). Along the Track (1930) details Croll’s journey to the Den of Nargun. Croll speaks of his pursuit to locate the Den of Nargun. As Croll looked for a place to sleep they were tempted by ‘sand under, a close canopy of bushes’, but their pursuit of ‘the cave’ encouraged their travelling souls (Croll, 1930: 80). In Along the Track, Croll (1930) provides his impressions of the week they spent at the Den of Nargun in 1923 (originally published in The Argus, 2/6/1923):

A tinkling of bell-birds suggested water, and, sure enough, well shaded by overhanging growths, we found some isolated pools, from which, eventually to draw a meal of mountain trout and a fine eel. Above the second pool a rock barrier, thirty feet high, stretched from wall to wall, and apparently, forbade all further passage. It must make an attractive waterfall when the stream runs. On the right the water has undercut the cliff to a depth of about forty feet and for a length of 150 feet, forming a habitable cave, dry, and practically waterproof. In this Ngrung a Narguna (home of the stone devil) as the natives named it to Howitt, we lived for five days, and a comfortable home it provided. Blocks and stones fallen from the roof provided seats and tables, ledges of the back wall seemed made for storing provisions, and the easterly aspect of the opening allowed the glorious moon for last Easter to flood it with light every evening. … Despite the dreams that should have come in such a place, we saw nothing of the original owner, the nargun, described as “all stone, but his breast, and his arms and his hands”, who lurked in caves to devour people, and against whom all weapons were useless. But one night we woke to a dreadful scream, which drove all sleep away. Near at hand in the gorge followed a blow as though a blunt axe had struck hollow timber. ‘Hough’, ‘hough’, ‘hough’ went the flail-like beat until a dozen or more had been struck. Then all was silence. In the morning we saw no sign of the mysterious visitor. The sun shone, the birds sang and disported; the evil spirit had been exorcised (Croll 1930: 80-81).

In December 1926, Charles Daley led a party of ten members of the Field Naturalists Club of Victoria on a Christmas excursion to Deadcock Creek and the Mitchell Gorge. Of the Den of Nargun, Daley wrote the following:

The towering cliffs, the beautiful, lofty trees, the striking features of the cave, the “Nargun’s Den,” the twisting lianas, the attractive beauty of the setting, with its strangeness and harmonious blending of color and form, compose a picture that can only be imperfectly described, but will long live in memory. It is unique, a place apart, a restful retreat, secure in its situation from storm or devastating tire affecting the hills above (Daley, 1927: 300).

In the 1930s the Field Naturalists Club of Victoria–which was founded in 1880 and continues to operate at different locations throughout Victoria–began instigating movements to have the site protected. In 1938 they had some success when the area of Woolshed Creek including the Den of Nargun was declared a sanctuary (Field Naturalists Club of Victoria, 2012; Catrice, 1996). It wasn’t until the 1950-60s that interest in protecting the sight was in the forefront again.

The Bairnsdale Field and Naturalist Club appealed to the public for support in protecting the Den of Nargun through the publication of an article in the Bairnsdale Advertiser in 1962 titled An Early Account of Visit to the Den of Nargun. The article retold Howitt’s journey to the site and states that:

Efforts are being made by the Bairnsdale Shire Council to have a large tract of country, including the Den of Nargun area in the vicinity of the junction of Dead Cock Creek and the Mitchell River, declared a National Park…The [Field and Naturalist] Club is also of the opinion that the area should be preserved as National Park… (Bairnsdale Advertiser, August 1962).

Following appeals as illustrated in the Bairnsdale Advertiser (1962), in another article ‘To the Den of Nargun Majestic Cove’ published in the Gippsland Pictorial News in December 1962, it was announced that ‘This month the “dens” on Deadcock Creek and the adjacent land were proclaimed a National Park’. The article proceeded to increase exposure to the site through restating how to get there:

Follow Dargo road to Den of Nargun sign and along turn-off to gate. Pass a cattle grid and gateway in two miles to stopping point for vehicles (near deserted house). Follow house in general left direction into scrub. Trail is overgrown but easy to follow. Mitchell Gorge appears after about a mile. Walk to river and turn upstream to creek bed. Turn left to lower shelf of rock. Up small track at bottom end of overhang, along creek bed for mile to upper den.

Shortly after the declaration of Deadcock Creek (including the Den of Nargun) as a National Park, the area including Woolshed Creek Sanctuary was renamed to form the Glenaladale National Park in 1963, following the donation of 163 adjoining hectares from Australian Paper Manufacturers Ltd. In 1963 the Den of Nargun was formally registered as part of the Glenaladale National Park (Harvey, 2007; Catrice, 1996). Naturalist Norman Wakefield (1967: 5) confirmed that the Glenaladale National Park was established by Government gazettal on 13 November 1963, and that its focal point was the geological formation known as ‘Den of Nargun’. Wakefield (1967: 8) notes that ‘For many years the Den of Nargun and its surroundings were privately owned, and the general area was eventually acquired by Australian Paper Manufacturers Ltd. However, that firm generously agreed to donate the 403½ acres to the Victorian Government, and thus it was possible for the place to be made a National Park’.

On March 22, 1965, a letter was sent to the National Museum of Victoria from R.S. Yeates, from the Bairnsdale Historical Society. This letter highlights increased visitation following the creation of the Glenaladale National Park. It is unknown whether anything eventuated from this letter; however it goes some way to substantiating an increase in tourism numbers as reflected by the bell-shape curve in Butler’s (1980) tourism area life cycle model. Another key development occurred in 1980 when the Den of Nargun was registered as an historic site by the Australian Heritage Database (Australian Government, 2011).

In terms of Gunn’s (1994) spatial model the nucleus is surrounded by the inviolate belt which can function to protect and enhance, both physically and geographically, the natural and cultural sanctity of the nucleus. The inviolate belt was essentially fabricated in 1938 with the declaration of the Woolshed Creek Sanctuary and then reaffirmed in 1963 when the Den of Nargun became protected under the Glenaladale National Park and reaffirmed in 1980 (Australian Government, 2011; Harvey, 2007; Catrice, 1996). Physical barriers to protect the geological formation of the nucleus, and thus function as an inviolate belt, were not constructed. However, the natural plunge pool and rock formations may have acted to provide some natural protection by deterring tourists from entering the cave itself.

5.3 Third Phase: Enshrinement 1986–Present

MacCannell’s (1976) third phase in the evolution of attractions is known as ‘enshrinement’. This takes place when the site has graduated from framing and elevation and proceeds to increased exposure and visitation. Aligned with this stage is the continuation of Butler’s (1980) tourism area life cycle model including three stages ‘development’, ‘consolidation’ and ‘stagnation’. Development is characterised by changes in site structures and facilities in order to increase positive tourism experience and cope with tourism demand that continues to increase due to well sought and developed marketing plans set out in the prior involvement stage. Visitor numbers will continue to increase resulting in the graduation into the stage of consolidation. Marketing progresses focussing on an increase in economy driven advertising as the local economy becomes more prominently shaped by the tourism industry.

The next stage identified by Butler (1980) that corresponds with the enshrinement period described by MacCannell (1976) is stagnation. Stagnation will be a result of the tourist attraction reaching its ‘[c]apacity levels for many variables will have been reached or exceeded, with attendant environmental, social, and economic problems’ (Butler, 1980: 8). Butler (1980) also suggests that initial site attractiveness which initially drew people to the nucleus will supersede as a result of social and cultural changes rather than the physical attractiveness of the site. Corresponding with MacCannell’s model and Butler’s tourism area lifecycle model is the ‘zone of closure’ described by Gunn (1994). The zone of closure is the final stage presented in the spatial model and represents the area surrounding the nucleus and inviolate belt. Typically, the zone of closure refers to visitor services and facilities which promote accessibility and enhance the visitor experience (Gunn, 1994).

The enshrinement stage began in 1986 when the Den of Nargun became a part of the Mitchell River National Park. The Mitchell River National Park formed when the Glenaladale National Park and other adjoining land was merged to form one title (Catrice, 1996). This change in composition of land in which the Den of Nargun is situated increased exposure to the site. Increased exposure occurred as a result of the Mitchell River National Park offering a variety of different tourist and leisure attractions. The Mitchell River National Park offers camping, four-wheel driving and leisure opportunities in the south end of the park where the Den of Nargun is located. The Den of Nargun was also promoted through the newly-created Bataluk Cultural Trail which was developed in order to increase exposure of Aboriginal sites and increase Indigenous tourism in Gippsland (Parks Victoria, 1998).

The Bataluk Cultural Trail website notes:

The Nargun is a large female creature who lives in a cave behind a waterfall in the Mitchell River. The Den of Nargun is a place of great cultural significance to the Gunaikurnai people, especially the women. Traditionally Gunaikurnai men were not allowed down to the Den of Nargun or the Woolshed Creek valley. Gunaikurnai men respected this traditional law and still do today. Please treat this place with respect. Stories were told around campfires about how the Nargun would abduct children who wandered off on their own. The Nargun could not be harmed with boomerang or spears. These stories served the dual purpose of keeping children close to the campsite and ensuring that people stayed away from the sacred cave. The Den of Nargun is a special place for women and may have been used for women’s initiation and learning ceremonies. The walk into the Den takes approximately 15 minutes each way, or 45 minutes as a circuit walk via the Mitchell River. Note that there are some steep sections along the walk.

The zone of closure identified by Gunn (1994) includes the existing Den of Nargun Picnic Area, Woolshed Creek Camping Grounds, Old Weir Lookout, Deadcock Bend and Billy Goat Bend Camping Grounds (Parks Victoria, 2011). Den of Nargun Picnic Area facilities included toilets, fireplace, picnic tables, shelter and lookout (Parks Victoria, 1998). It is believed that from 1986 when the Mitchell River National Park formed, the majority of tourist facilities were constructed marking the beginning of Butler’s (1980) development and consolidation stage.

By 1998, visitor statistics gathered by Parks Victoria showed that Mitchell River National Park attracted approximately 56,000 tourists annually with one of the most popular sites for exploration being the Den of Nargun. The management authority, Parks Victoria, responded to these figures in order to sustain tourism numbers and promote positive tourism experiences (Parks Victoria, 1998). Major development to the Mitchell River National Park and the Den of Nargun’s immediate zone of enclosure (walking track, access roads and Den of Nargun Picnic Area) began in 1998 and are identified in the Mitchell River National Park Management Plan. In 1998 the proposed park improvements relative to the Den of Nargun, included upgrading the service road between Billy Goat Bend and the Den of Nargun from open to public to Class 1 which allows full 2WD access; installing interpretive signage at Den of Nargun Picnic Area and along walking tracks to the nucleus highlighting the cultural and natural significance of the Den of Nargun; increasing car parking at Den of Nargun Picnic Area; and enhancing the existing facilities and creating recreation opportunities at the Den of Nargun to increase visitor enjoyment (Parks Victoria, 1998) (see Fig.5.4).

Since the Mitchell River National Park Management Plan was proposed and implemented in 1998, there is little evidence of any significant interventions or development at the Den of Nargun (Parks Victoria, 1998). The only exception is the removal of the lookout at the Den of Nargun somewhere between 1998 and 2007 (Harvey, 2007; Parks Victoria, 1998). Harvey (2007) has also suggested that the interpretive signage is out dated and needs to be improved.

Nevertheless, two events have occurred since the 1998 management plan that have significance for the Den of Nargun. Firstly, the announcement of the joint management between Parks Victoria and the Gunaikurnai Land and Water Corporation for the Mitchell River National Park. Parks Victoria (2012: 1) notes:

On Friday the 22nd of October 2010 both the Federal and State Governments formally recognised the Gunaikurnai people as the Traditional Owners of over 20 percent of public land within Gippsland and Eastern Victoria. The Victorian Government and Gunaikurnai people formally signed Victoria’s first settlement agreement under the new Traditional Owner Settlement Act 2010. This agreement involved a transfer of the ten parks and reserves to the Gunaikurnai “Aboriginal Title” which will be jointly managed in conjunction with Parks Victoria. Mitchell River National Park is one of the jointly managed parks within Gippsland. This agreement recognises the fact the Gunakurnai people have always been connected to their land and are the rightful people to speak for that country. These parks and reserves are cultural landscapes which are part of our living culture.

Whilst this announcement signals a change to pre-existing management structures which promotes greater Indigenous ownership, there is no evidence to suggest that dual management has had any effect on tourism at the Den of Nargun. However, this is a significant event in the Den of Nargun’s history.

The only other known major intervention since the 1998 management plan is the rejuvenation of the Bataluk Cultural Trail in 2011 (which features the Den of Nargun). The Bataluk Cultural Trail tourist information brochure and website were redesigned and new sites in South Gippsland and Cape Conran were added to the self-directed tour (ABC Melbourne, 2011; Bataluk Cultural Trail, N.D.a; Bataluk Cultural Trail, N.D.b). In the following section, it will be argued that the Den of Nargun is still in the enshrinement phase identified by MacCannell (1976) and stagnation stage described by Butler (1980).

5.4 Fourth Phase: Duplication

The next phase in the evolution of natural attractions identified by MacCannell is ‘duplication’ or ‘mechanical reproduction’. Mechanical reproduction refers to the deliberate act of producing products and artefacts inspired by the nucleus or site. These can include things such as copies of the nucleus, photographs, paintings, and postcards. MacCannell (1976: 45) suggests that the purpose of this phase, whether deliberate or unintentional is to set ‘the tourist in motion on his journey to find the true object’.

Duplication of the Den of Nargun has been evident through the production of various artworks and writings over the past 40 or so years. As tourism and awareness of the Aboriginal site increased from the 1950s, duplication of the nucleus also occurred. The Nargun, the supernatural being, has been portrayed in numerous story books including The Slaughter of the Bulumwaal Butcher by Bruce Pascoe, Lingio (1866) by Angus McLean, and The Ghost Child (2008) by Sonya Hartnett. Additionally, Pearson Australia has published a primary school learning resource about the Den of Nargun (Pearson, N.D.). However, the most famous storybook written about the Nargun was that published by the acclaimed Australian author Patricia Wrightson. Wrightson first published The Nargun and the Stars in 1973 (see Fig.5.5). The storybook was re-published in 1988 with drawings by Robert Ingpen (Wrightson, 1988).

Wrightson’s (1988: 7) story begins:

It was night when the Nargun began to leave. Deep down the below the plunging walls of the gorge it stirred uneasily. It dragged its slow weight to the mouth of its den; its long, wandering journey had began. Two hundred feet above, on the broad uplands, moon light whitened the gum-trees where eagles were building. It split into the gorge to touch the tallest heads of coachwood and nettle-tree, but it never reached the black damp rocks of the bottom. Only where water slid over a great slab of cliff at the head of the gorge a glint silver light was carried down. At the bottom the water fell, with a sound-and-echo like guitar strings, into a pool that spanned the gorge. Behind this pool – behind a bead-curtain of falling water – cut broad and low into the base of the cliff was the arch way of a cave. This was the ancient den of Nargun. Here it had lain while it learnt fly and gum-trees to blossom; while stars exploded and plants wheeled and the earth settled; while the cave opened; while dripping water hollowed a pool from rock and filled it, and drop by drop built crystal columns before the cave. And all this while the Nargun slept. In time it opened slow eyes and saw light. Little by little it dragged itself from earth and moved. There came a night when it had a voice and cried down the gorge. There came a day when, crouching in shadows, it grasped at something warm and found food to mumble on. After that it ate when it could; sometimes once in ten years, sometimes in fifty. It moved down the gorge to blink at the sun, to watch a river flow, to hunt savagely; but always it made the ponderous climb back, crushing ferns and grinding moss on its way to drag itself behind the crystal columns…

Photographs and paintings of the Den of Nargun have been appearing online for many years. For example, photographers such as Dave Callaway captured the Den of Nargun and currently sells his images online (Red Bubble, 2012). Local Indigenous artist Eileen Harrison painted an image in 2005 that depicts Aboriginal women at the Den of Nargun. The caption on the painting reads ‘[c]oming down towards the river, as you watch, spirits watch over you. The protectors of the boulders represent beauty of the forest. The black trees are blackened through fire’ (Culture Victoria, 2010). The same image features in the book Meerreeng-An Here is my Country (Keeler & Couzens 2010: 46). Russel Mullet, a Kurnai man, shares his story about the Nargun: ‘me-mandook grandmother ghee-yin tell dyerrak fear tukai child bitja fire ngarwu listen wangin-mirri hear’ meaning ‘after dark, we would sit around the fire and the old people would tell stories about Mrarts and Doolagahs and Narguns. In our imagination, they were something like Big Foot, big hairy men, wild men, and the Narguns were their wives’ (Keeler & Couzens, 2010: 46).

It is proposed that the Den of Nargun as a cultural and natural tourism attraction has not reached Butler’s period of decline or rejuvenation. Rather, it is still in a period of stagnation. Firstly, as stated by Butler (1980) decline occurs when the nucleus becomes less attractive to the tourist. There is no statistical evidence that supports a decrease in site attractiveness. Upon visiting the Den of Nargun in January 2013, the picnic area appeared to be well maintained with the facilities all above average. It is argued that if the Den of Nargun was experiencing a period of decline, the facilities and structures would not be maintained to the perceived good standard. Conversely, it is also believed that the Den of Nargun is not experiencing rejuvenation. If rejuvenation was to occur, it would be a result of clear and well planned strategic management and marketing plans (Butler, 1980). Given that the most current management plan is from 1998 there is little evidence to suggest that dramatic interventions at the site have occurred in recent years. Therefore, it is argued that the site and its features are in a period of stagnation. The only known form of tourist focussed rejuvenation is the restructuring of the Bataluk Cultural Trail in 2011 (ABC Melbourne, 2011). Overall the site is continuing to be maintained at a reasonable standard contributing to the argument that the Den of Nargun has not yet entered rejuvenation or decline.

5.5 Fifth Phase: Social Reproduction

For MacCannell (1976), the final stage of sight sacralization is social reproduction which occurs when groups, cities, and regions begin to name themselves after famous attractions. In the case of Den of Nargun it has not been possible to locate any instances of social reproduction.

5.6 Tourism at the Den of Nargun

The Den of Nargun has a long history of tourism for both natural and cultural reasons. Since its European discovery by explorer and natural scientist Alfred William Howitt in 1875 it has progressed into a tourist site with the first large influx of tourists in the 1930s (Australian Government, 2011; Catrice, 1996). The Den of Nargun continues to attract over 50,000 visitors annually. Its successful tourism history can be attributed to its aesthetic and Indigenous values and history. The conglomerate cavern formation of the cave is believed to have been formed over 36 million years ago and is the largest cave of this formation on record (Harvey, 2007; Department of Environment and Primary Industries, 2012). This unique and picturesque site attracts visitors. The supernatural being believed to inhabit the cave provides the tourist with a unique and enlightening experience. Table 5.1 outlines critical moments in the history of tourism at the Den of Nargun.

Tab. 5.1: Den of Nargun: a timeline

Year |

Event |

1875 |

European discovery by Alfred William Howitt. |

1884 |

Local selector J.D. Stocks ‘discovers’ the Den of Nargun. |

1886 |

Journalist Julian Thomas aka ‘The Vagabond’ publishes account of a visit to the Den of Nargun. |

c. 1900 |

Discovered by the Morrison Brothers, local landholders. |

1904 |

Morrison Brothers return to site with Professor Stanley Porteus |

1923 |

Noted bushwalker, R.H. Croll documented the Den of Nargun and its location in newspaper accounts and in his guidebooks -‘The Open Road’ (1928) and ‘Along the Track’ (1930). |

1926 |

Charles Daley and a party of the Field Naturalists Club of Victoria visit the Den of Nargun. |

1930 |

Large influx of tourists. |

1938 |

Den of Nargun and the area of Woolshed Creek were declared a sanctuary. |

1963 |

Den of Nargun registered as part of the Glenaladale National Park. |

1980 |

Den of Nargun registered as an historic site by the Australian Heritage Database. |

1986 |

Den of Nargun became part of the Mitchell River National Park. |

1998 |

Parks Victoria management intervention and site development. Estimated tourists to the Mitchell River National Park were 56,000 annually. |

2007 |

Harvey published the Conservation Analysis Report: The Den of Nargun |

2010 |

Mitchell River National Park joint management plan between Parks Victoria and Gunaikurnai Land and Water Corporation. |

According to Butler’s (1980) tourism area life cycle model, a tourist site will experience either rejuvenation or decline following stagnation. The Den of Nargun is still in a period of stagnation and it may enter a period of decline if there is not any further tourism management interventions initiated by the managing bodies Parks Victoria and Gunaikurnai Land and Water Corporation. There are also concerns about protecting the nucleus from tourism impacts. Harvey’s (2007) report highlighted some key areas for improvement in order to sustain tourism at the Den of Nargun. Firstly, the interpretative signage at the Den of Nargun Picnic Area and along the track to the den itself is out-dated. Harvey (2007: 6.5.3) writes ‘the signage at the den needs to be updated and expanded, with greater emphasis given to the importance of this special place’. This statement was confirmed by the first named author during a recent visit to the Den of Nargun where there was only one sign with limited interpretation located sixty metres from the nucleus. Whilst the facilities at the Den of Nargun Picnic Area are well maintained, the walking track has become heavily eroded in sections making it difficult to navigate. The current structure of the walking track limits accessibility for people with young children or low physical capabilities. This needs to be considered because if the track continues to erode the ability to view the nucleus will be severely compromised.

There are also concerns that there is a lack of intervention to minimise tourists entering the cave (Harvey, 2007). Park Ranger Yasmin Aly, has noted ‘We have a walking track to the Den and we’re trying to manage people wanting to sit in the Den which they shouldn’t do because of the cultural significance. I’d like to see more input from the community, perhaps…developing a working group with the local women in the indigenous community so we can refer to them when we have issues such as the Den of Nargun access’ (Environment Victoria n.d.). Despite the majority of stalactites formed on the exterior of the den and interior of the cave being broken off by tourists, there has been no intervention such as the construction of a grille or some other barrier that would act as a physical inviolate belt to reduce degradation and tourism impacts. Parks Victoria (1998: 16) stated that they aim to ‘[m]inimise the impacts of visitor and management activities on significant geological features’. Furthermore, The Department of Primary Industries (2012) expresses concerns about the tourism impact on the aesthetic value of the Den of Nargun. However, the nucleus remains unprotected with no deliberate attempt to install an inviolate belt. Overall, these notions need to be considered if the sight/site is to continue to provide positive tourism experiences in future.

5.7 Conclusion

The Den of Nargun, set in the Mitchell River National Park in Gippsland, approximately 50km from Bairnsdale, has had a successful tourism history since its European discovery in 1875. This study has attempted to document the development of the site utilising the theoretical constructs developed by MacCannell (1976), Butler (1980) and Gunn (1994). MacCannell’s progressive development of attractions amalgamated with Butler’s tourism area life cycle model has provided systematic insight into the different phases which occurred since the Den of Nargun’s discovery to its current maturation. The investigation into the tourism history of the Den of Nargun was further enhanced through application of Gunn’s spatial model which provided insight into the contextual setting of the nucleus and its surrounding environment. Potential areas for site improvements presented by Harvey (2007) were supported by photographic evidence and anecdotal analysis at the site in January 2013.

Although ‘discovered’ by Europeans in 1875, the Den of Nargun did not begin to experience significant numbers of visitors until the 1930s largely through the agency of bushwalkers and field naturalists. Although the site was declared a ‘sanctuary’ in 1938, formal site protection did not take place until November 1963 when the private company, Australian Papers Manufacturers Ltd, donated 163 acres that included the cave that saw the formation of the Glenaladale National Park. In 1986 the Glenaladale National Park was merged with adjoining land and renamed the Mitchell River National Park. Today, the site is managed by Parks Victoria and the Gunaikurnai Land and Waters Corporation.

References

ABC Melbourne. (2011). Breakfast with Gerard Cullinan: Bataluk Cultural Trail. Retrieved 8 December 2012 from http://blogs.abc.net.au/victoria/2011/12/bataluk-cultural-trail.html

Australian Government. (2011). Place Details: Den of Nargun, Walpa, Victoria. Retrieved 8 December 2012 from http://www.environment.gov.au/cgibin/ahdb/search.pl?mode=place_detail;place_id=103369

Australian Heritage Places Inventory. (N.D.). Den of Nargun. Retrieved 8 December 2012 from http://www.heritage.gov.au/cgi-bin/ahpi/record.pl?RNE103369

Bairnsdale Advertiser August 1962; 26/1/1884

Bataluk Cultural Trail. (N.D.a). Explore the Bataluk Cultural Trail. Retrieved 8 December 2012 from http://www.batalukculturaltrail.com.au/index.php Bataluk Cultural Trail. (N.D.b). Bataluk Cultural Trail brochure.

Billis, R.V. & Kenyon, A.S. (1974). Pastoral Pioneers of Port Phillip. Melbourne: Stockland Press.

Butler, R.W. (1980). The concept of tourist area cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. Canadian Geographer, 24:5-12.

Calder, J. (1990). Victoria’s national and state parks. Melbourne: Victorian National Parks Association.

Catrice, D. (1996). Victoria’s Heritage: Mitchell River National Park. Melbourne: Parks Victoria.

Clark, I.D. (2007). The abode of malevolent spirits and creatures – caves in Victorian Aboriginal social organization. Helictite, 40(1):3-10.

Croll, R.H. (1928). The Open Road in Victoria: Being the Ways of Many Walkers. Melbourne: Robertson & Mullens.

Croll, R.H. (1930). Along the track. Melbourne: Robertson & Mullens.

Culture Victoria. (2010). Indigenous Culture: Meerreeng-an Here is my Country Den of Nargun. Retrieved 7 December 2012 from http://www.cv.vic.gov.au/stories/meerreeng-an-here-is-my country/10699/den-of-nargun/

Daley, C. (1927). The Mitchell Gorge Excursion. Victorian Naturalists Journal, xliii: 297-302.

Department of Environment and Primary Industries. (2012). 8322-5 Den of Nargun. Retrieved 9 December 2012 from http://vro.dpi.vic.gov.au/dpi/vro/egregn.nsf/pages/eg_lf_sites_significance_8322_5

Environment Victoria. (N.D.). Yasmin Aly: A River Love Affair. Retrieved 7 December 2012 from http://environmentvictoria.org.au/content/yasmin-aly

Etheridge, R. (1893). Note on an Aboriginal Skull from a Cave at Bungonia. Records of the Geological Survey of New South Wales, 3(Pt. 4):128-131.

Field and Naturalist Club of Victoria. (2012). Retrieved 12 December 2012 from http://www.fncv.org.au/welcome.htm

Gippsland Pictorial News, December 1962

Google Maps. (2013). Get Directions: A) Glenaladale, Victoria B) Mitchell River National Park, Cobannah, Victoria. Retrieved 14 January 2013 from https://www.google.com.au/maps.

Gunn. C. (1994). Tourism planning: Basic, concepts, cases (3rd ed.). Washington: Taylor and Francis.

Harvey, P. (2007). Conservation Analysis Report: The Den of Nargun. Bairnsdale: East Gippsland Institute of TAFE.

Hartnett, S. (2008). The ghost’s child. Camberwell: Penguin Books.

Howitt, A.W. (1875). Notes on the Devonian rocks of North Gippsland. Third report of progress, Geological Survey of Victoria, 181-249.

Howitt, M. (1971). Come Wind, Come Weather: A Biography of Alfred Howitt. Carlton: Melbourne University Press.

Keeler, C. & Couzens, V. (Eds) (2010). Meerreeng-an Here is my Country: the story of Aboriginal Victoria told through Art. Melbourne: Koorie Heritage Trust.

McLean, A. (1866). Lindigo. Melbourne: H. T Dwight.

MacCannell, D. (1976). The tourist: A new theory of the leisure class. New York: Schocken Books.

Massola, A.G. (1962).The Nargun’s Cave at Lake Tyers. Victoria Naturalist, 79(5):128

Massola, A. (1969). Journey to Aboriginal Victoria. Adelaide: Rigby Limited.

Parks Victoria. (1998). Mitchell River National Park Management Plan. Retrieved 14 December 2012 from https://www.parkweb.vic.gov.au/__.../Mitchell-River-National-Park-ManagementPlan.pdf

Parks Victoria. (2011). Park Notes: Mitchell River National Park.

Parks Victoria. (2012). Park Notes: Mitchell River National Park.

Parks Victoria. (2013). Mitchell River National Park. Retrieved 9 January 2013 from http://parkweb.vic.gov.au/explore/parks/mitchell-river-national-park

Pascoe, B. (1986). The slaughters of the Bulumwaal butcher. Anthology of Australian Literature. Australia: Allan & Unwin

Pearson Australia (N.D.). Unit 16: Den of Nargun. Retrieved 9 January 2013 from http://www.pearson.com.au/media/297909/pdf-literature-word-up-grammar1-u16-page-proofs.pdf.

Pepper, P. (1980). You are what you make yourself to be: the story of a Victorian Aboriginal family 1842-1980. Melbourne: Hyland House.

Porteus, S.D. (1951). Providence ponds: a novel of early Australia. Bairnsdale: James Yeates and Sons.

Red Bubble. (2012). Den of Nargun by Dave Callaway. Retrieved 12 December 2012 from http://www.redbubble.com/people/davecall/works/9170715-den-of-nargun?p=greeting-card

Seddon, G. (1989). Searching for the Snowy. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

Smyth, R.B. (1878). The Aborigines of Victoria. 2 Vols. Melbourne: Victorian Government Printer.

Wakefield, N.A. (1967). Naturalist’s Diary. Melbourne: Longmans.

Wheeler, G. (1991). The Scroggin Eaters: a history of bushwalking in Victoria. Melbourne: Federation of Victorian Bushwalking Clubs Inc.

Wrightson, P. (1973). The Nargun and the stars. Richmond: Hutchinson. [1988, Hawthorn: Hutchinson].

Yeates, R.S. (1965, March 22). Mr. E.D. Gill, assistant director, National Museum of Victoria, Melbourne. Bairnsdale Historical Society.

Images

Culture Victoria. (2010). Indigenous Culture: Meerreeng-an Here is my Country Den of Nargun. Retrieved 12 January 2013 from http://www.cv.vic.gov.au/stories/meerreeng-an-here-ismycountry/10699/den-of-nargun/

Fig. 5.1 : The Den of Nargun (Sharnee Sergi, 2013)

Fig. 5.2: ‘“Ngrung-A-Narguna” A cave in Dead Cock Creek Mitchell River’ A.W. Howitt (1875: facing page 220).

Fig. 5.3: A shooting Party at the Den of Nargun in 1905 (Source: Courtesy of Department of Environment and Primary Industries, Victoria)

Fig. 5.4: Den of Nargun picnic area (Sharnee Sergi, 2013)

Fig. 5.5: The Nargun and the Stars (1974) cover

24 Phillip Pepper (1980: 57) recounts a story of a group of Ganai men including Big Charlie, Big Joe, and Short Harry who killed a Nargun in a cave near Tooloo. Pepper describes the Nargun as ‘seven feet tall and went out at night to hunt the children and eat them’. It was also called the ‘Hairy Man’.

25 Edmund Spenser – The Faerie Queene, Book 1.9.

26 Mount Yasur is an active volcano on Tanna Island, Vanuatu.

27 In ancient Greek mythology, Lamia was a Libyan queen who became a child-eating daemon.

28 Kanooka refers to Tristaniopsis laurina, or water gum – a medium native rainforest tree with a widely spreading canopy.