Telehealth in Primary Health Care

Analysis of Liverpool NHS Experience

E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]

Abstract

This chapter describes a feasibility study that examined user experience of a telehealth system within a local area in the United Kingdom. The telehealth system was designed by Philips (called Motiva) and piloted within Liverpool National Health Service (NHS) Primary Care Trust (PCT), United Kingdom. The telehealth system operates a dual interface and real-time data transfer mechanism that allows patients to upload and monitor vital signs (e.g., weight and blood pressure) from their own homes, which are comonitored by clinicians to provide adequate intervention. The pilot project spanned a period of 6 months, and a questionnaire/interview study was conducted among the two user groups (i.e., patients and clinicians); prior to this, a pilot study was used to uncover their experiences. Questionnaire responses were recorded from 24 patients with various Long Term Conditions (LTC), and four of them were followed up for a one-to-one interview. Questionnaire and interview responses were recorded from 12 clinicians (including 7 Matrons, 3 Nurses and 2 GPs). The data analysis showed: 87.5% of patients were satisfied with the telehealth system; 87.50% received more support at home; 91.67% understood and managed their condition better, and 95.83% felt re-assured knowing that their readings were comonitored by clinicians. There are proven indications that hospital/general practitioner visits were reduced as a result. Clinicians’ results were also positive, with 85.71% expressing their satisfaction with the pilot system and telehealth technology in general. Telehealth holds great promises for improving clinical management and health care services delivery by enhancing access, quality, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness.

Keywords

National Health Service (NHS); Telehealth; Patient Experience; Vital Signs; Clinical Management; Community MatronsIntroduction

Characteristics of the Motiva Pilot Project

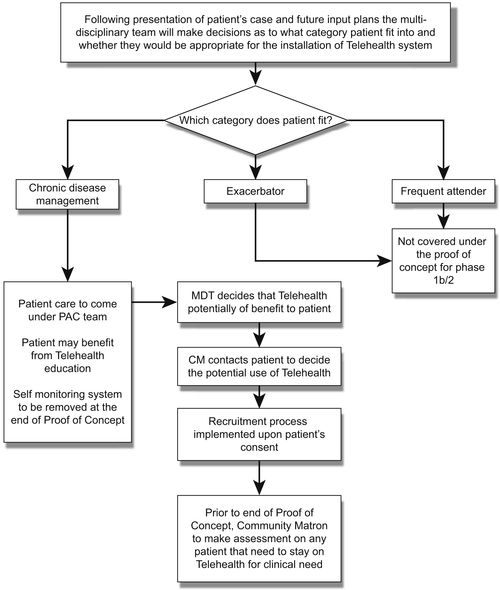

Cohort Recruitment and Time Scales

Method

Table 13.1

Key Lines of Inquiry Covered in the Quantitative (Paper) Study

| Section No. | Patients’ Questionnaire | Clinicians’ Questionnaire |

| Section 1 | First impressions about Motiva (4 embedded questions) | First impressions about Motiva (4 embedded questions) |

| Section 2 | Effects of Motiva on care pathway (12 embedded questions) | User satisfaction/performance (4 embedded questions) |

| Section 3 | User perception (15 embedded questions) |

Table 13.2

Key Lines of Inquiry Covered in the Qualitative (Oral) Study

| Question | Semistructured Interview with Patient(s) |

| 1. 2. 3. 4. | Highlight the most negative/positive aspect(s) of the Motiva system from your point of view Did you learn anything new from the process? Is there anything else about being involved in the telehealth project that you wish had been different? Is there anything else you think we have not covered on the questionnaire with regards to your experience? |

| Semistructured interview with clinician(s) | |

| 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. | Highlight the most positive/negative aspects of the project? Did you learn anything new about telehealth technology in general? How has the use of telehealth affected the tasks you would normally undertake? That is, has the load increased or decreased? Do you feel more confident about new technology now? Is there anything else about being involved in the project you wish had been different—including those not covered in the questionnaire? |

Analysis and Result

Patients

Questionnaire Section 1: First Impressions (Embedded Questions 1–4)

Questionnaire Section 2: Effects of Motiva on Care Pathway (Embedded Questions 5–16)

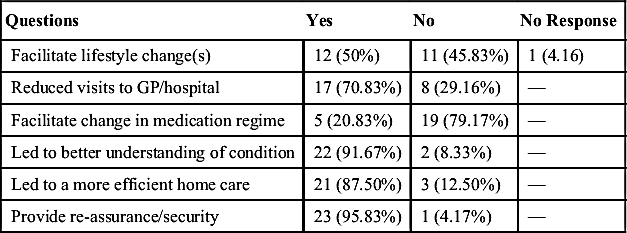

Table 13.3

System Effects of Motiva on Patients’ Care Pathway

| Questions | Yes | No | No Response |

| Facilitate lifestyle change(s) | 12 (50%) | 11 (45.83%) | 1 (4.16) |

| Reduced visits to GP/hospital | 17 (70.83%) | 8 (29.16%) | — |

| Facilitate change in medication regime | 5 (20.83%) | 19 (79.17%) | — |

| Led to better understanding of condition | 22 (91.67%) | 2 (8.33%) | — |

| Led to a more efficient home care | 21 (87.50%) | 3 (12.50%) | — |

| Provide re-assurance/security | 23 (95.83%) | 1 (4.17%) | — |

Questionnaire Section 3: User Perception (Embedded Questions 17–31)

Table 13.4

Abstract of User Responses to the Relevance of Educational Videos

| Q | Was enough effort made to encourage you? (20 responded) |

| A | They all agreed that enough effort was made. |

| Q | What encouraged you? (13 responded) |

| A | Most respondents agreed that the videos came-up automatically and were easy to follow. One patient added, “….understanding my condition and how I could try to ease my breathing.” Another wrote, “felt less isolated knowing other people unfortunately have similar problems.” |

| Q | What did you find most useful about the videos? (15 responded) |

| A | Most respondents agreed they were informative, providing clear explanation of their condition. Some wrote that the videos helped them make lifestyle changes. |

| Q | What was not so useful about the videos? (7 responded) |

| A | Of the 7 respondents, 6 found everything useful, with one adding, “Was on a course so I knew some of the information.” However, one respondent found the videos frightening, adding that “it revealed the dangers associated with bad management.” |

| Q | What additional videos would you like in the future? (7 responded) |

| A | Respondents were mostly satisfied with available videos but one of them added that they would like to see statistics showing how they compared to others with similar condition, in terms of management. |

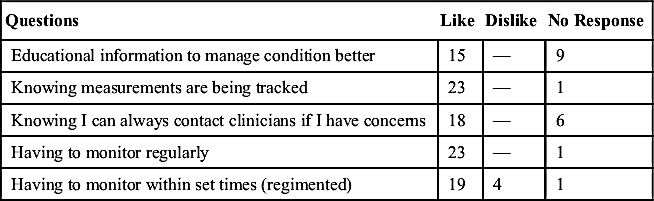

Table 13.5

Patients’ View of Liked and Disliked Elements of Motiva (Quantitative)

| Questions | Like | Dislike | No Response |

| Educational information to manage condition better | 15 | — | 9 |

| Knowing measurements are being tracked | 23 | — | 1 |

| Knowing I can always contact clinicians if I have concerns | 18 | — | 6 |

| Having to monitor regularly | 23 | — | 1 |

| Having to monitor within set times (regimented) | 19 | 4 | 1 |

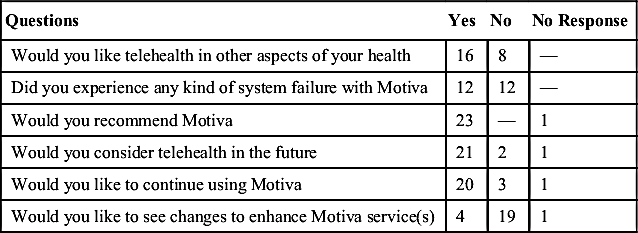

Table 13.6

Patients’ Experience/Perception of Motiva and Telehealth in General

| Questions | Yes | No | No Response |

| Would you like telehealth in other aspects of your health | 16 | 8 | — |

| Did you experience any kind of system failure with Motiva | 12 | 12 | — |

| Would you recommend Motiva | 23 | — | 1 |

| Would you consider telehealth in the future | 21 | 2 | 1 |

| Would you like to continue using Motiva | 20 | 3 | 1 |

| Would you like to see changes to enhance Motiva service(s) | 4 | 19 | 1 |

Semistructured Interview (Four Embedded Questions)

Table 13.7

Patients’ View of Positive and Negative Aspects of Motiva (Qualitative)

| Positive(s) | Negative(s) |

| Ability to visualize and track measurements Easy to use Boosts confidence Reassured knowing that measurements are being tracked by clinicians Educative and effected lifestyle changes | Frequency of measurement, especially weight. System failure/Internet connectivity issues |