Without theory, practice is but routine born of habit.

—Louis Pasteur

He who loves practice without theory is like the sailor who boards ship without a rudder and compass and never knows where he may cast.

—Leonardo da Vinci

The quest for an explanation is a quest for theory.

—Hans Zetterberg

Theories are the tools we use to understand the world. We must realize, however, that all theories are not created equal and that some ways of creating and verifying theories are better than others. The explanation that disease was caused by an imbalance of certain substances in the body, which could be rectified by blood-letting, was bogus. It was based on an invalid observation that human bodily fluids contained four “humors”—yellow and black bile, phlegm, and blood—and on the erroneous logical inference that an excess of one of them, blood, was the cause of many diseases.

Theories abound at the intersection of human kind’s yearnings for knowledge and the desire to make a fast buck (e.g., weight loss supplements and get-rich schemes come immediately to mind). The popular press in the form of business periodicals such as The Wall Street Journal, Forbes, and BusinessWeek offers a treasure trove of postmortems on organization’s that have failed or are failing, helping readers understand what caused their demise and, implicitly at least, offering advice on how to better manage their organizations. Additionally, many books have attempted to answer the age-old question, “What makes a business successful?” Some of the more popular of these books with strong marketing implications are: Jim Collins’ Good to Great; In Search of Excellence, by Tom Peters and Robert Waterman; and What Really Works, by William Joyce, Nitin Nohria, and Bruce Roberson. All of these publications offer “theories” of a sort. Many are simple explanations based on personal interviews, heresay, and secondary data with little if any application of scientific reasoning or methods, such as testing hypotheses. Don’t get me wrong, they are excellent books. But they primarily specify hypotheses; they don’t rigorously test them (although Collins’ book does contain rigorous analyses), which is one way in which theories are justified.

Our focus is on how a marketing manager can develop theories to inform decision making. “Applied” theories are more formal than those published in the popular press but not as formal as theories in academic journal articles. We want to strike the right balance, so let’s begin with our first definition of theory from Chapter 2:

For now, consider a marketing theory to be your best explanation for a current or expected marketing phenomenon. There are, of course, good and bad marketing theories. Good theories have two key elements. First, they enhance our understanding of marketing phenomenon (“Why was Product X so successful?”) Second, they have some predictive power. They enable us to forecast with some level of confidence how a manager might successfully affect market outcomes—to make Product X successful.

Keep in mind that the term theory is misunderstood in the business world. For many, it implies “unproven,” “impractical,” “academic,” or “unfeasible.” In contrast, from a scientific point of view, a good theory explains and predicts patterns that we observe in nature. It enhances our understanding of marketing phenomenon. The process of developing theories creates knowledge and informs belief systems. It is only through theories that management can most effectively justify beliefs on which marketing strategies and tactics are based. Theories are, quoting Leonardo da Vinci, your “rudder” and “compass.”

The remaining discussion introduces you to the following expanded topics on theory:

• Two broad categories of theoretical investigations.

• A more specific definition of theory for marketing mangers.

• The nature of laws in marketing.

• An applied example of a marketing theory: explanatory sketches.

Two Broad Categories of Theoretical Investigations

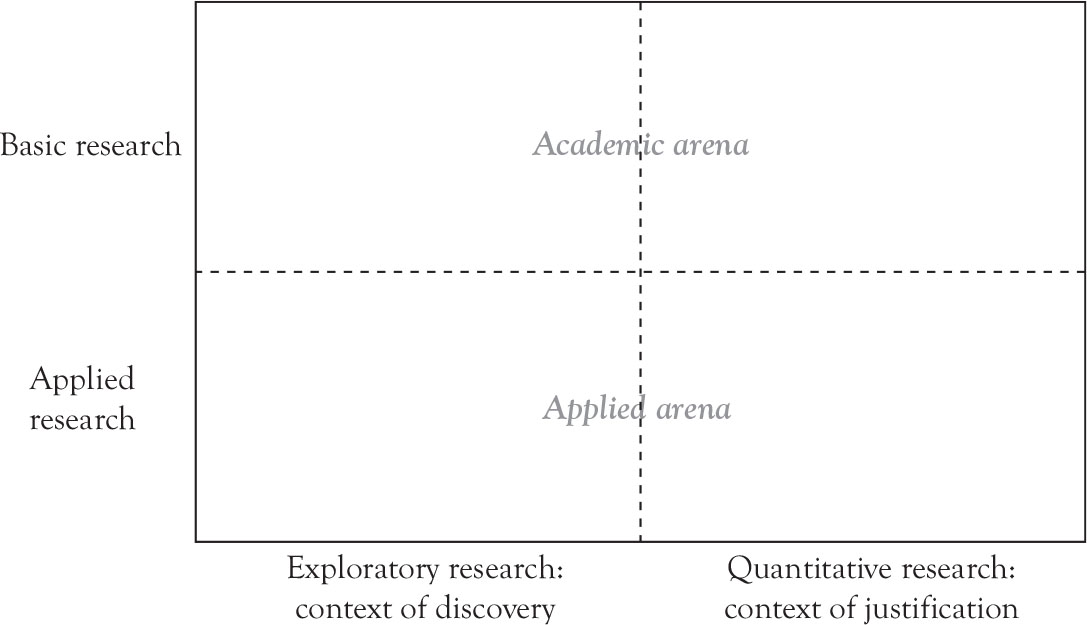

Consider Figure 12.1. In the field of marketing, theoretical investigations are conducted in two general areas—academia and marketing organizations—and along two paths, one that takes you on the path toward the discovery of knowledge (“context of discovery”) and the other toward its justification (“context of justification”).

Figure 12.1. Theory development in academic and applied settings.

Basic and Applied Research

Basic research “seeks to expand the total knowledge base of marketing.”1 For example, investigating factors that contribute to the perception of “service quality” is basic research. In contrast, applied research “attempts to solve a particular company’s marketing problem.”2 Understanding factors that influence the service quality of a particular financial institution, such as Bank of America, is an example of applied research.

Discovery and Justification

The context of discovery is the first phase of theory development and knowledge creation, which often takes the form of exploratory research, often using John Stewart Mill’s methods of induction discussed in Chapter 10. The second phase is called context of justification where you quantitatively test your theories and hypotheses.

For applied marketers such as yourself, the context of discovery phase might involve interviewing a small sample of industry experts and consumers about some marketing issue, examining relevant published sources of information, or investigating internal sales data to develop preliminary hypotheses regarding some marketing phenomenon of interest, such as “Why did our last product launch fail?” It is in this context of discovery phase where you need some knowledge of those generalizable theories that professors write about in textbooks and journal articles. Then, you need to apply and tailor them to better understand the markets that you manage.

For example: Whether you are establishing a pricing strategy or developing a new product, you should be aware of Weber’s Law. This is not so much a marketing law as it is a law of perception—with marketing applications. Weber’s Law states that the just-noticeable difference (JND) between two physical or psychological stimuli is proportional to the magnitude of the stimuli.3 The marketing implications of Weber’s Law are straightforward:

Manufacturers and marketers endeavor to determine the relevant JND for their products for two very different reasons: (1) so that negative changes (e.g., reductions in product size or quality, or increases in product price) are not readily discernible to the public (i.e., remain below the JND.), and (2) so that product improvements (e.g., improved or updated packaging, larger size, or lower price) are very apparent to consumers without being wastefully extravagant (i.e., they are at or just above the JND). For example, some years ago in an apparent misunderstanding of the JND, a silver polish manufacturer introduced an extension of its silver polish brand that prolonged the shine of the silver by months but raised its product price by merely pennies. By doing so, the company decreased it sales revenue because the new version cannibalized sales of the old product and, at the same time, was purchased much less frequently than the old version. One marketing expert advised the company to double the price of the new product rather than make it just slightly more expensive than the old one.4

Weber’s Law has application across a wide variety of marketing decisions such as defining the minimum price reduction needed to stimulate department store merchandise sales, how to price a family of “good–better–best” products, and determining how much product quality needs to be improved to be noticed.5

Bottom line: Successful marketers require some basic familiarity with marketing theories relevant to the markets they serve. For example, all marketers need a basic understanding of Weber’s Law. Additionally, if you are involved in developing your organization’s marketing communications, you need some familiarity with theories that explain how advertising works. A good place to start is to acquire a copy of Advertising and Promotion: An Integrated Marketing Communications Perspective, by George E. Belch and Michael Belch, 9th edition, McGraw-Hill Irwin. See the Additional Readings chapter for suggestions.

An Expanded Definition of Theory

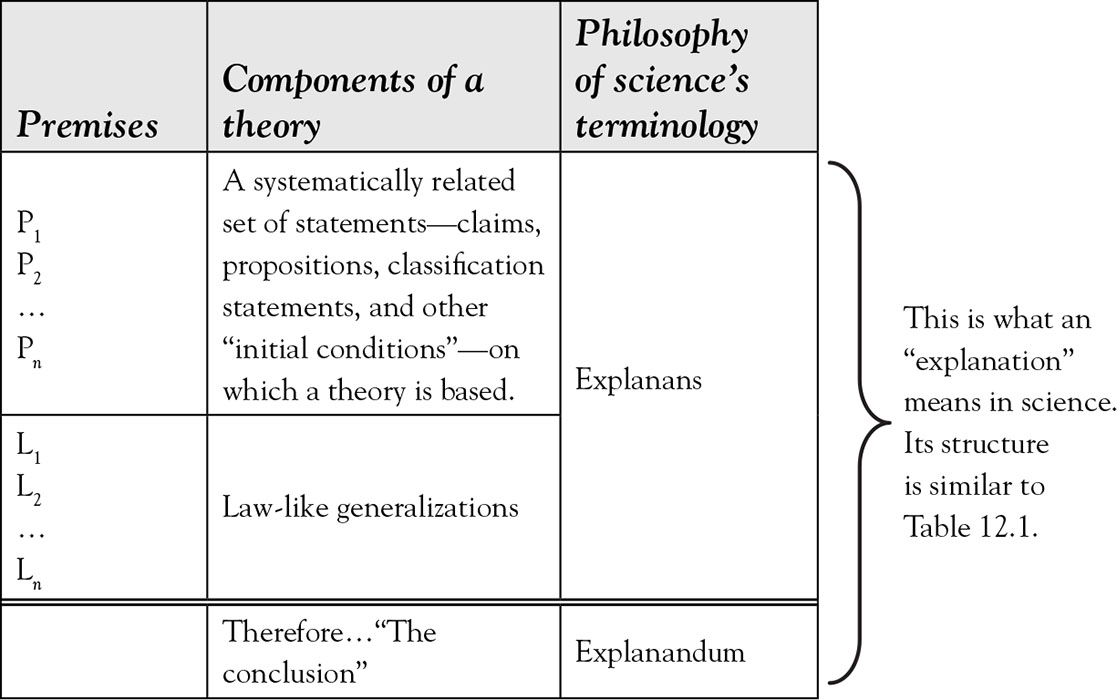

A widely accepted definition of theory comes from Richard Rudner’s book, Philosophy of Social Science, in which he defines a theory as “a systematically related set of statements, including some law-like generalizations that are empirically testable. The purpose of theory is to increase scientific understanding through a systematized structure capable of both explaining and predicting phenomena.”6

A “systematically related set of statements, including some law-like generalizations” is simply a set of premises that is used to explain a conclusion (refer to Chapter 11 on Arguments and Logical Fallacies). The example below uses a set of premises and law-like generalizations to explain a hypothetical marketing outcome, in this case the expected increase in demand for a product as a result of a price reduction.

The premises identify the assumptions and circumstances underlying the marketing outcome you are trying to explain and the law-like generalizations that, when combined with these premises, logically suggest a likely outcome. You might associate “laws” with physics and think marketing cannot have similar “laws,” but it does. We do have laws in marketing and I will be talking more about them shortly.

Table 12.1 reflects the general structure guiding theory development in science. Table 12.2 shows this general framework and how law-like generalizations figure into theories.

Table 12.1. Components of a Theory

|

Components of a simple theory |

|

|

Premises |

Examples |

|

A systematically related set of statements |

1. The price of Product X is $Y 2. Quantity q of Product X is sold over time period t 3. Product X reduces its price by 10% |

|

Law-like generalizations |

4. Weber’s Law 5. Law of Supply and Demand |

|

Conclusion (Marketing outcome) |

Therefore, demand for Product X increases over time period t |

Table 12.2. The General Structure of a Theory

In a theory, the stuff that does the explaining is called the explanans (ex’-pla-nans’), and the conclusion or what is being explained (e.g., market share for Product X did or is likely to decline) is the explanandum (ex’-pla-nan’-dum). As you can see in Table 12.2, a theory is a form of an inductive argument.

More simply, good theories are genuine explanations. Genuine explanations, as explained by Dr. Garret Merriam, assistant professor of Philosophy at the University of Southern Indiana:

• Give us a good conceptual grasp of phenomena

• Accord well with our understanding of the world [Chapter 9: Coherence]

• [Help us to] exercise control over previously uncontrollable situations

◦ In short, a genuine explanation takes something that we don’t understand and puts it in terms of something we do understand.7

Merriam’s third point about exercising control over previously uncontrollable situations is why theory development is so practical for marketers. Theories give marketers understanding, which, when properly combined with a well-designed marketing mix, give you the potential to influence consumer brand purchasing patterns. Part of this understanding is related to uncovering cause-and-effect relationships in markets that are law-like in nature.

The Nature of Laws in Marketing

If you are skeptical about law-like relationships in marketing, think about the following law-like claims:

• Customer satisfaction is related to repeat brand purchase.

• If you increase your product’s price too much, customers will stop buying it.

• If your product’s quality diminishes too much, market share will suffer.

• A small percentage of your customers provide most of your sales (e.g., Pareto’s Law).

Marketers assume that marketing events happen for reasons. And theories go a long way to help marketers understand how these events come about, and what they can do to influence them. Back in the early 1980s, the tagline on management consulting firm Arthur D. Little’s promotional brochure read, “We help manage change.” That’s what theory development is all about—understanding change in markets that is driven, in part, by law-like relationships. The best marketers try to understand marketing’s laws.

So what is a law-like generalization in marketing? We’ve already discussed two—Weber’s Law and the Law of Supply and Demand. The end of this chapter lists 11 additional marketing laws from Byron Sharp’s excellent and informative book, How Brands Grow.

In the context of marketing, a law-like generalization reflects a necessary relationship that exists in a marketing arena. Law-like generalizations contain the following desirable properties (there are more, but for our purposes, we’ll focus on these): necessity, prediction, validity, and understanding. To simplify my discussion, when I talk about law-like generalizations, I always mean such generalizations developed within the context of a theory.

Necessity

A law-like generalization in marketing holds that there are certain necessary cause-and-effect type relationships in markets. These law-like generalizations “… explain precisely because they are not generalizations about what always happens. They are much stronger claims about what must happen … .”8 Jeffery L. Kasser, a philosophy professor at Colorado State University, likes to say that laws put the “cause” in “because.”

Keep in mind, however, that markets are made up of human beings. Consequently, these law-like generalizations, in the context of behavioral research, are not deterministic; they are probabilistic in nature (see Chapter 8 on causation for a review of this concept). Additionally, they are not as constant as the laws of physics. As new products are created and some products are retired, destroyed, or evolve, new law-like generalizations may arise, and existing ones can change or become irrelevant. Certainly, the current activity associated with social media and Internet advertising is bringing about new and evolving law-like relationships describing how consumers and organizations influence each other. How such marketing laws are manifested in particular markets—such as those reflected in Weber’s Law—differ by market and product. Marketing professors are primarily concerned with discovering law-like relationships that generalize across marketing phenomena. In contrast, marketing practitioners are (or rather should) be concerned about how these law-like relationships manifest themselves in their particular markets. (This, perhaps, is the major justification for conducting marketing research.)

Prediction

Predictive power is a necessary condition for any good law-like generalization. Indeed, it is this necessity for prediction in the scientific practice of testing theories that is the motivation behind testing new medications in the pharmaceutical industry. Predictability is also a pragmatic requirement for any marketing manager who wants to develop and use theories to help inform decision making because it helps to guide changes in a marketing strategy—“Changing our product in certain ways is likely to increase our market share by X and our profits by Y.”

For applied marketers, testing the predictive power of a law-like generalization is a double-edged sword. It may be desirable, but it is also expensive and time consuming. All organizations have limited resources and are under time constraints. And what do you do if you work for an organization that does not have a marketing research department that might be able to test your theories? Here is my advice:

• First, conduct secondary research to discover whether any academic research has been done in the same general area around which your strategic recommendation is based. For example, if you go to Google Scholar you can find articles examining theoretical marketing models developed for a wide variety of industries such as general retailing, wine, pharmaceuticals, chemicals, nonprofits, and services. Basic college-level textbooks on strategic marketing, consumer behavior, and marketing communications may also identify relevant, tested theories that can provide support for your initiatives.

• Second, employ scientific reasoning and other methods discussed in this book to examine the coherence of the beliefs supporting your recommendations (Chapter 9: Coherence). Is your logic sound (Chapter 10: Logic)? Are your arguments strong (Chapter 11: Arguments and Logical Fallacies)? Are you being objective (Chapter 4: Barriers to Scientific Reasoning).

• Finally, given the constraints you are operating under, do the best you can.

Validity

In this context, I am using a different definition of “validity” than I did in Chapter 10 about deductive logic. Regarding deductive logic, validity is a property of a deductive argument. A deductive argument is said to be valid if “it is logically impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion false.”9 But if the premises are indeed false or implausible, a deductive argument—even though it is logically “valid”—won’t be sound. Regarding a law-like generalization, validity refers to the inherent truth of what is being claimed. In other words, does a law-like generalization accurately describe a necessary relationship—is it at least approximately true?

Now, let’s not get bogged down in a philosophical discussion of “truth.” You have a business to run, and for you to run it, you have to assume that there are statements or propositions about markets that are either true or false, or apply a certain percentage of the time, under certain conditions, to a certain percentage of consumers. How one develops and validates law-like generalizations is a book unto itself. Here’s my advice on how to begin developing these law-like hypotheses for the markets you manage:

• Chapter 13 gives brainstorming ideas on how to come up with hypotheses regarding law-like generalizations describing your markets.

• Read relevant marketing journals. There are some professional marketing journals that target specific industries and many more general journals that contain articles that focus on specific industries. An example of the former is the Journal of Retailing. An example of the latter is Marketing Science. For instance, a November–December 2011 article in Marketing Science focuses on the pharmaceutical industry and how physicians process contradictory information about products.10

• Read Byron Sharp’s book, How Brands Grow, in which he discusses 11 law-like relationships in marketing.

• If you have a marketing research department, conduct primary research to help identify and test law-like relationships in the markets you serve.

Understanding

Law-like generalizations should help us better understand marketing phenomena such as consumer purchasing behavior. For example, which of the two (overly simplified for discussion purposes) law-like generalizations provides more understanding?

1. Consumers purchase products they like.

2. Consumers possess beliefs about product attributes such as aspects of a product’s perceived quality and price competitiveness. Some attributes are more influential than others for consumers. Consumers tend to purchase those products that are perceived to perform best on the most influential attributes.

The first generalization is too vague. The second set of general statements is more specific and provides greater understanding.

Where do you discover these law-like generalizations? There are several ways. One is simply to conduct research in your own market. Talk to consumers and industry experts to understand factors driving brand choice. Another is to read about marketing theories in textbooks or articles and consider how they might apply to your markets.

A relatively new field of intellectual inquiry (new to many of us in marketing, at least) is called Behavioral Economics (BE). BE is providing great insights into how human beings make decisions, and it lies at the intersection of the mind and perception, or what Daniel Kahneman calls, WYSIATI—What You See Is All There Is. You might say that Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman christened the field of BE in their 1974 Science article, Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases.11 Kahneman’s recent book, Thinking, Fast and Slow—a New York Times best seller—provides a summary of his, Tversky, and others’ major contributions to BE over the past nearly 40 years.12

Findings from BE can shed light on law-like generalizations describing product choice. For example, there is a concept in BE called “anchoring.” Anchoring is a psychological effect influencing a decision, brought about by exposing a person to a number or a value of a quantity.13 For example, as Kahneman recounts in his book, a grocery store in Sioux City, Iowa, would often place its Campbell’s soup on sale at 10% off. Sometimes the sale was accompanied by a sign reading “No Limit per Person,” and at other times, “Limit of 12 per Person.” On average, twice as many cans per person were sold when the store displayed the “rationing” sign. The “anchor,” in this situation was the number “12.” (It is beyond the scope of this book to discuss the psychological mechanisms that bring the anchoring effect into play. Read Kahneman’s book. Additionally, over time, consumer learning can trump anchoring. If every time you went to that Sioux City grocery store and saw the rationing sign, yet the store never seemed to be out of Campbell’s soup, you’d catch on.)

Additional marketing examples from BE have shown that playing slower versus faster background music in a store can increase the average sale per customer; providing consumers with too many choices or information on products can result in consumers relying more on a sales clerk’s recommendation than evaluating product brands on their own merits; and, changing a package’s design—while not changing the product—can improve consumers’ perceptions of product quality and influence brand switching.14

An Example of an Applied Theory

Before giving you an example of an applied theory, I need to review the concept of beliefs because they play a critical role in developing theories. Recall that in Chapter 2 a belief is broadly defined as “what we accept to be true.” In marketing, in the context of the example I present shortly, a belief is more narrowly defined as how much of a given attribute is perceived to be possessed by a product. These two definitions are really saying the same thing but come from two different perspectives. The definition of belief in Chapter 2 is what you might find in a philosophy textbook, and it applies to any field of study. A belief about a product, which is the focus of our example, translates into “marketing language” as follows:

A product attribute belief is what consumers accept to be true about a product with respect to how much of a given attribute a product is perceived to possess.

Therefore, if you accept the assertion that Product X is a high-quality product, your acceptance of that assertion is your belief about Product X with respect to its quality.

Now to our example: Recall Brunswick’s acquisition of the Sea Pro saltwater boat brand that I discussed earlier in the book:

Brunswick had been successful in acquiring fresh-water boat brands such as Crestliner, Lowe, and Lund, and then sold them with Mercury Marine engines, a Brunswick subsidiary. In 2005, Brunswick acquired the saltwater boat brand, Sea Pro, for $51 million. Prior to this acquisition, Sea Pros primarily came with Yamaha engines. At that time, Yamaha and Honda had the lion’s share of outboard boat engines in the salt water market (and still do today). Sales of Sea Pro plummeted when consumers discovered that they could not get their preferred Yamaha engine on a Sea Pro boat and in 2008, Brunswick shuttered the Sea Pro brand.

Figure 12.2 presents a hypothetical (and simplified) framework identifying boat and engine attributes, around which consumers formed beliefs, which, in turn influenced the purchase of saltwater fishing boats. Table 12.3 incorporates these beliefs together with other premises to develop four systematically related sets of statements and two law-like generalizations, which, together, form a proposed theory explaining the failure of the Sea Pro acquisition.15

Figure 12.2. Hypothetical theoretical framework identifying consumer beliefs influencing the purchase of salt water fishing boats.

This theory is based on an inductive argument that gives a strong reason to believe the conclusion (see Chapter 10 on logic for a discussion of inductive and deductive arguments). The theory or argument is inductive because the premises, if true, do not guarantee the conclusion. However, the argument is strong because:

Table 12.3. A Proposed Theory Describing the Demise of the Sea Pro Brand

|

“A systematically related set of statements” |

|

|

Premises |

Nature of statement |

|

1. Purchasers of saltwater boats possess beliefs about boat performance attributes that influence their brand selection. |

An assumption based on marketing theory suggesting that consumers possess beliefs about products, and these beliefs influence brand choice. |

|

2. The purchase of a saltwater boat is a high involvement decision. |

Classification statement describing the level of consumer involvement in a boat purchase. |

|

3. The primary boat performance attributes that affect decision making are (a) Boat Brand Quality, (b) Engine Brand Quality, (c) Engine HP, (d) Boat Handling Quality, and (e) Price. |

Observation statement based on past marketing research. These premises are what we observe in studying consumer brand purchasing behavior toward the salt water boat category in which Sea Pro competes. |

|

4. The most critical factors influencing brand purchase are, in order of influence, (b) and (a). |

Observation statement based on past marketing research. |

|

“Law-like generalizations” |

|

|

5. A significant majority of consumers who consider the Sea Pro brand will only purchase that brand if it carries a Yamaha engine on its transom, all other factors held constant. |

This law-like inference is based on past marketing research and judgment. |

|

6. If the brands in a given consumer’s consideration set all offer Yamaha engines, then perceived boat brand quality will determine choice, all other factors held constant. |

Based on the lexicographic heuristic theory of consumer choice, discussed below. |

|

Conclusion (Outcome) |

|

|

Demand for the Sea Pro brand of saltwater boat will decline if those who are considering the brand are not allowed to purchase it with a Yamaha engine. |

|

• The premises on which the conclusion is based are all empirically based and highly plausible; and

• The inference from the premises to the conclusion is logically sound.

What’s more, the law-like generalizations are based on all information that is known about this consumer and market, and the lexicographic heuristic theory of consumer choice, which Leon G. Schiffman and Leslie Lazar Kanuk define as follows:

“…a non-compensatory decision rule in which consumers first rank product attributes in terms of their importance, and then compare brands in terms of the attribute considered most important. If one brand scores higher than the other brands, it is selected; if not, the process is continued with the second ranked attribute, and so on.”16

Since the engine brand is the most influential factor affecting brand choice in this product category, once Brunswick forced prospects to purchase a Sea Pro with a Mercury Marine versus a Yamaha engine, demand for Sea Pro fell, reflecting a law-like relationship that existed in the market—similar to the Law of Supply and Demand—that necessitated Brunswick’s failure.

By the way, I am not using hindsight’s 20/20 vision to explain what we already know happened. A modest investment in marketing research prior to Sea Pro’s acquisition would have quickly uncovered the risk of switching out Yamaha for Mercury Marine engines. Moreover, some Brunswick and Mercury Marine executives were not surprised at what eventually befell Brunswick in this transaction.

Thinking Tip

What makes for a good theory, especially one that you might develop for a selected market? Below is a list of characteristics that apply both to you and to the renowned physicist Stephen Hawking:

1. Understanding: By all means, a good theory enhances your understanding. Whether you’re trying to understand how social media influences consumers in your market, why consumers purchase one brand over another, or how to develop a pricing strategy, the process of developing a good theory will give you greater knowledge to make more effective decisions.

2. Clarity: In marketing, the strength of your ideas to persuade others is as much affected by how well they are communicated as by their merits. Refer again to Chapter 11 on constructing persuasive arguments.

3. Usefulness: As many others before me have said, there is nothing more practical than a good theory. Marketing managers use theory to make better decisions. As Timothy Rey from The Dow Chemical Company said in Chapter 3, “It’s all about the money.”

4. Coherence: The theories you develop for your business should cohere with more general marketing theories that come out of academia. For example, if you have a significant marketing communications budget, the rationale supporting your communications strategy should be grounded in generally accepted theories about marketing communications.

5. Occam’s Razor: This comes from William of Occam, a fourteenth-century English Franciscan friar and philosopher. His idea was to have as few assumptions, premises, and law-like generalizations in your theory as needed to explain a given phenomenon. In the example in Table 12.1, there are four premises and two law-like generalizations than can explain the demise of Sea Pro. Having superfluous assumptions, premises, or law-like generalizations that offer no additional explanatory power to a theory are simply not useful.

6. Scope: Say you work for a consumer packaged goods company (CPG). What good is a theory explaining product brand choice for a household cleanser if it only is predictive of consumers shopping on Saturday afternoons? I know this is a silly example, but you get my gist. Generally, the greater a theory’s scope, the better the theory. But there is an ideal level of scope in the eyes of a marketing manager. For instance, academic marketing theories are generally too broad in range to be useful for a marketing manager. But, these more general marketing theories can often be tailored to your specific situation.

How Do I Use What I Just Read?

Your ability to build theories will, in part, be a function of the resources you are given to develop them. This book is written for all marketers—those who have access to marketing research departments and those who don’t. Consequently, I want my answer to this question to be useful for all. If you have the luxury of having a marketing research department to test your theories, all the better.

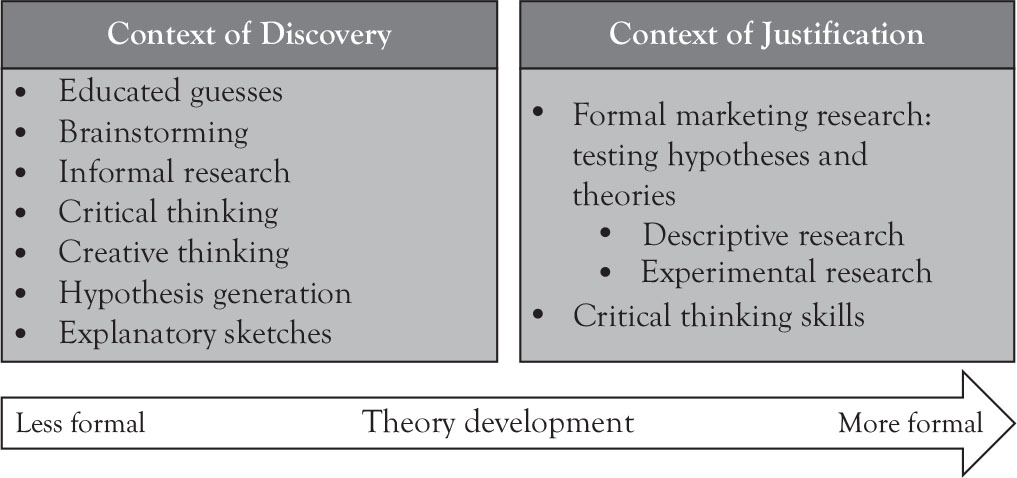

Figure 12.3 describes the various stages in developing a theory for a given market. Just because you may not be able to spend money on primary marketing research studies does not mean that you cannot develop preliminary theories—more appropriately called “explanatory sketches”—to help guide decision making. In fact, one could argue that the items listed under Context of Discovery are even more critical for those who are unable to test theories empirically. Conducting a thorough Context of Discovery phase is better than conducting an incomplete one, and then relying primarily on formal research in the Context of Justification phase. Why? Because a poorly conducted Context of Discovery often results in measuring the wrong things and asking the wrong questions in the Context of Justification phase—thus giving you wrong or misleading answers.

Figure 12.3. Theory development process.

Perhaps the most universal first steps in developing explanations of marketing phenomenon are simply to use your own background knowledge to make educated guesses and brainstorm with colleagues—“Why do you think our product failed? Here’s what I think.”

Yet, even at this early stage of knowledge development, critical thinking skills discussed in this book can help you ask the right questions and avoid using vague and ambiguous terms that can cloud your thinking. Example topics we’ve covered in previous chapters that will help you in this regard are as follows:

• Identify factors that actually motivate brand choice. Don’t ask what is “important” to consumers” (Chapter 2).

• Be aware that we all sometimes see associations in marketing phenomenon that corroborate our preconceived notions but that simply are not there (Chapter 4).

• Don’t let your worldviews color your perceptions of reality (Chapter 5).

• Think about constructs, not attributes (Chapter 7).

• Think about cause-and-effect relationships that influence consumer brand choice (Chapter 8).

• Make sure your preliminary theories are as coherent and truth-conducive as possible (Chapter 9).

• Use ILE to help form your theories (Chapter 10).

• Make sure your theories are logically sound and have plausible premises (Chapter 11).

The next chapter introduces you to several critical thinking methods to help you develop preliminary theories during the Context of Discovery phase of knowledge creation.

Chapter Takeaways

1. Knowledge is created by developing good theories. That’s what the best science does. Marketers should do the same.

2. A theory is our best explanation for a current or expected marketing phenomenon. There is nothing more practical than a good theory.

3. Most of us are familiar with theory development taking place in the academic arena (i.e., basic research). At least tacitly, it occurs in the applied arena of marketing, because all marketing decisions are based on some kind of understanding of a market. Better theories, however, lead to better understanding and better decisions.

4. Consequently, applied marketers should become committed to creating more formal theories to help improve decision making. Using Weber’s Law is an example of how marketers can use existing theory to create new and better theories tailored to the markets they serve.

5. This chapter outlines the components of a theory—a set of premises, together with at least one law-like generalization, to support a conclusion. To do this, refer to the example I give in this chapter, as well as an expanded discussion of how this is done in in Shelby D. Hunt’s book, Marketing Theory.17

6. There are law-like relationships in marketing (e.g., Weber’s Law and the Law of Supply and Demand). Byron Sharp’s book is dedicated to explaining the roles many law-like generalizations play in marketing.18 Defining the role law-like relationships play in your markets is the first step in understanding the dynamics of market change, and how you can and cannot influence that change (e.g., why do consumer preferences for brands change and what can you do about it).

7. Below are initial steps you need to take to develop a strong theory:

a. Identify factors that actually motivate brand choice. Don’t ask what is “important” to consumers (Chapter 2).

b. Be aware that we all sometimes see associations in marketing phenomenon that corroborate our preconceived notions but that simply are not there (Chapter 3).

c. Don’t let your worldviews color your perceptions of reality (Chapter 4).

d. Think about constructs, not attributes (Chapter 6).

e. Think about cause-and-effect relationships that influence consumer brand choice (Chapter 7).

f. Make sure your preliminary theories are as coherent as possible, and truth-conducive (Chapter 8).

g. Use ILE to help form your theories (Chapter 9).

h. Try to identify law-like relationships that exist in the markets you serve.

Marketing Laws Discussed in How Brands Grow, by Byron Sharp19

Double jeopardy law: Brands with less market share have so because they have far fewer buyers, and these buyers are slightly less loyal (in their buying and attitudes).

Retention double jeopardy: All brands lose some buyers; this loss is proportionate with their market share, i.e., big brands lose more customers (though these lost customers represent a smaller proportion of their total customer base).

Pareto law, 60/20: Slightly more than half of a brand’s sales come from the top 20% of the brand’s customers. The rest of the sales come from the bottom 80% of customers (i.e., the Pareto law is not 80/20).

Law of buyer moderation: In subsequent time periods heavy buyers buy less often than in the base period that was used to categorize them as heavy buyers. Also, light buyers buy more often and some non-buyers become buyers. This regression to the mean phenomenon occurs even when there is no real change in buyer behaviour.

Natural monopoly law: Brands with more market share attract a greater proportion of light category buyers.

User bases seldom vary: Rival brands sell to very similar customer bases.

Attitudes and brand beliefs reflect behavioural loyalty: Consumers know and say more about brands they use more often, and they think and say little about brands they do not use. Therefore, because they have more users, larger brands always score higher in surveys that assess buyers’ attitudes to brands.

Usage drives attitude: (or I love my Mum, and you love yours): The attitudes and perceptions (about a brand) that a brand’s customers express are very similar to the attitudes and perceptions expressed by customers of other brands (about their brand).

Law of prototypicality: Image attributes that describe the product category score higher (i.e., are more commonly associated) than less prototypical attributes.

Duplication of purchase law: A brand’s customer base overlaps with the customer base of other brands, in line with their market share (i.e. a brand shares the most customers with large brands and the least number of customers with small brands). If 30% of a brand’s buyers also bought brand A in a period, then 30% of every rival brand’s customers also bought brand A.

NBD [Negative Binomial Distribution]-Dirichlet: A mathematical model of how buyers vary in their purchase propensities (i.e. how often they buy from a category and which brands they buy). This model correctly describes and explains many of the above laws. The Dirichlet is one of marketing’s few true scientific theories.

Reproduced by permission of Oxford University Press Australia & New Zealand, from How Brands Grow, by Byron Sharp, 2010, Oxford University Press, ©Byron Sharp.