Chapter 4

Building Strong Brands

A Market-Driven Success

The Market Opportunity

Historically, most industries are product driven. Inventors discover new gadgets. R&D labs are pressured to find new cures for diseases. Scientists make incredible breakthroughs constantly in the fields of computer technology. Only the consumer-packaged goods companies have consistently demonstrated the discipline of letting market opportunities shape tomorrow’s products and services.

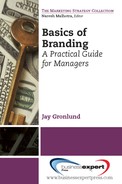

In reality, the development of a brand is not a linear process or step-by-step methodology. It starts with a multitude of different ideas that originate from the outside (marketplace) and the inside—for example, based on the vision, mission, and corporate values and/or a new product invention or improvements. However, as the product or brand evolves, it is critical to thoroughly examine the market at the outset, to create new ideas, to validate hypotheses for brand building, and to determine the market potential for a brand.

Researching the marketplace to understand the optimal brand opportunities should be an ongoing process, because the market (consumer behavior, competition, and category trends) is constantly changing.

A comprehensive analysis of the market situation is essential, but doing it well is not easy. In fact, the students in my NYU class have more trouble with this important first step than any other. I try to emphasize that a situation analysis does not mean a regurgitation of what is happening out there. The focus should be on what all these dynamics mean for the brand proposition, especially a fresh analysis of the targeted customer—that is, is there a clear market opportunity that the brand can capitalize on? It is really a systematic exercise in diagnostic learning and analysis, the engine for strategic brand creation. The aim is to interpret the external environment, together with the internal realities, to develop unique insights as the basis for creative brainstorming. If a corporate vision already exists, the ideal market assessment will be oriented so that it validates and reinforces it. The following are the key tasks of a typical market situation analysis:

• Definition: It may seem obvious, but the market structure, parameters, and main segments should all be clearly defined before other in-depth analyses proceed. There are several ways to segment a market. Ideally, these definitions should be developed to arrive at a relevant competitive frame of reference for the positioning statement.

• Target Customer: After concluding exactly who the primary customer should be (e.g., the potential heavy user), determine his/her needs, desires, and problems. In many situations, the decision-making act involves several people or roles, especially in B2B companies. A sense of a hierarchy of these needs, including the hidden wants and insights, is important. What exactly are their expectations today, and anticipated for tomorrow? Often, an additional or second target segment (e.g., influencers) can be crucial for building a brand, such as the medical community for the pharmaceutical industry.

• Competition: Who are the main competitors, and what are their strengths and vulnerabilities? How are they serving the market or consumer now? Are there nontraditional competitors who are offering a unique benefit today, or maybe tomorrow, that could become a threat?

• Industry Dynamics: Which trends are the most important for shaping the destiny of the brand? Do they pose threats or an opportunity? How will these trends affect the rules of success?

• Internal Capabilities: What are the key strengths that we can leverage to address these customer needs and achieve a competitive advantage? Can we deliver on the brand promises? Can we make a profit with the proposed pricing?

• Strategic Fit: Is the market opportunity and brand proposition consistent with the overall strategic mission and goals of the company?

• The Broad Environment: What is happening all around that may impact the business in the future: economic trends, social habits and attitudes, technological advancements, demographics, government regulations, etc.?

The sources of information for such a market assessment should be as diverse as possible to be able to cover every dimension or interpretation, especially for competitive and consumer benefit topics. Some common sources and types of data to focus on include the following:

• Review of existing consumer-related data

• Search engines such as Google

• Competitors’ advertisements and websites

• Online chat room for specific categories

• Ongoing external, environmental, and trend assessments

• Library for competitor information, trade journals, etc.

• Consumer-focus groups or interviews

• Industry experts and other professionals

• Consulting firms

• Sales force and distributor interviews

• Trade associations

The team that conducts this market situation analysis should be multidisciplined. Marketing and market research should spearhead much of this effort, but it is important to draw on other resources of the company, such as sales, R&D, production, IT, customer service. The main deliverable from this initial market assessment should be a set of new insights, defined as clear and simple diagnostic statements that can be readily understood by all. These key insights have a twofold role: modifying the overall business strategy and providing a foundation for creative ideation for developing and refining brand positioning.

Market Research for Brand Development—The Basics

One of the most common fallacies of marketing is the pervasive belief of “I know exactly how the consumer will respond ….” It is natural for marketers to feel convinced that the consumer will understand and fall in love with ideas that make the utmost sense on a rational basis. The thinking often goes like this: it really is an improvement. I understand and like it and after all I’m a consumer too, they must think like I do. I’m sure they will see this as the key difference from our competition, that the benefit is so obvious that maybe it isn’t even worth getting consumer feedback …

Experienced marketers have all shared such strong convictions, but most have been surprised in the past to discover that the consumer does not always feel the same way. Other marketers, especially those with limited experience, often go overboard and initiate massive studies that generate tons of information, where only a fraction of the results are really meaningful and actionable.

With all research, especially for brand development, it is important to be very clear upfront about what information you need and whether this can be used effectively. The purpose of market research is to assist in decision making, or to reduce the risk of poor decisions. When conducting research on positioning or strategy-related issues, one should keep in mind the many risks inherent in designing the methodology and interpreting research results. Some typical problems or challenges that marketers often face are the following:

• Consumer behavior is so complex that it can be very difficult to measure or project—it does not always reflect the real world, especially for purchase interest ratings

• Research can be biased or compromised to support preconceived ideas or opinions in politicized organizations

• Marketers sometimes see research as an exclusive device to make decisions (i.e., not as an aid), instead of one to reduce the risks of decision making

• There can be too much reliance on the procedures, and not the final judgment and/or action to be taken as a result

• “Must win” goals can be misleading and distort research—should be a guidance for learning, not simply a “pass/fail”

• Office politics can get in the way, providing an “escape” for managers

Essentially, there are two types of research: primary research and secondary or “desktop” research. The latter data collection type is ideal for market situation analyses, particularly when there are budgetary limitations. The internet (e.g., Google), libraries, industry associations, trade articles, and other similar sources can be invaluable for estimating the size and trends in certain markets, identifying the competition, understanding regulatory or legal issues, catching up on current technological trends, and learning about other market conditions. While this type of desktop research is easy and quick, the information is not always current or reliable.

Primary research is customized to provide specific feedback from a target customer group on topics such as consumer needs, usage and/or attitude, new ideas and concepts, positioning hypotheses, advertising, packaging, and so on. This specialized research form is either qualitative or quantitative, depending on the sample size. Qualitative research involves smaller audiences (e.g., focus groups, one-on-one interviews, mall intercepts, brief surveys), so the results are not projectable. The fastest growing form of qualitative research is online testing, which is replacing traditional telephone surveys and mall focus groups. All these types of small-scale research are relatively inexpensive and can be an excellent directional resource for new ideas.

Quantitative research requires larger numbers of participants, usually over 125 in the sample, so that the results can be statistically significant, and hence projectable within certain confidence parameters, depending on the specific audience size. There is a wide variety of different quantitative research methodologies, including general market studies, usage and attitude (U&A) studies, product/concept tests, tracking studies, controlled store tests, advertising copy and packaging testing, simulated market response tests, and so on. These traditional quantitative tests are more accurate for predicting behavior, but they also tend to be very expensive (well over $50,000), unless it is a simple, limited omnibus survey.

Online quantitative testing is an option that is very common today. The big advantage is cost. Depending on the specifications of the target participants, a projectable online test with over 100 people might cost approximately $7,500–15,000. However, there are some risks—for example, the quality of the panel of participants (verifying that the desired customer is actually answering behind the computer, completing the questionnaire), fewer questions, more limited diagnostic analyses, and so on.

“Issues” Should Drive Market Research

When I started my marketing career several years ago at Richardson-Vicks, I was both impressed and confused by their emphasis on the concept of “Key Issues” in all planning. We certainly had not covered this topic of key issues in any of my marketing courses in business school, and so it took me a while to fully understand how to apply this discipline. Management insisted that the issues be clearly defined in a strategic context, and that there should be only a few pertinent ones cited, set in priority of importance for achieving the brand’s strategic objectives.

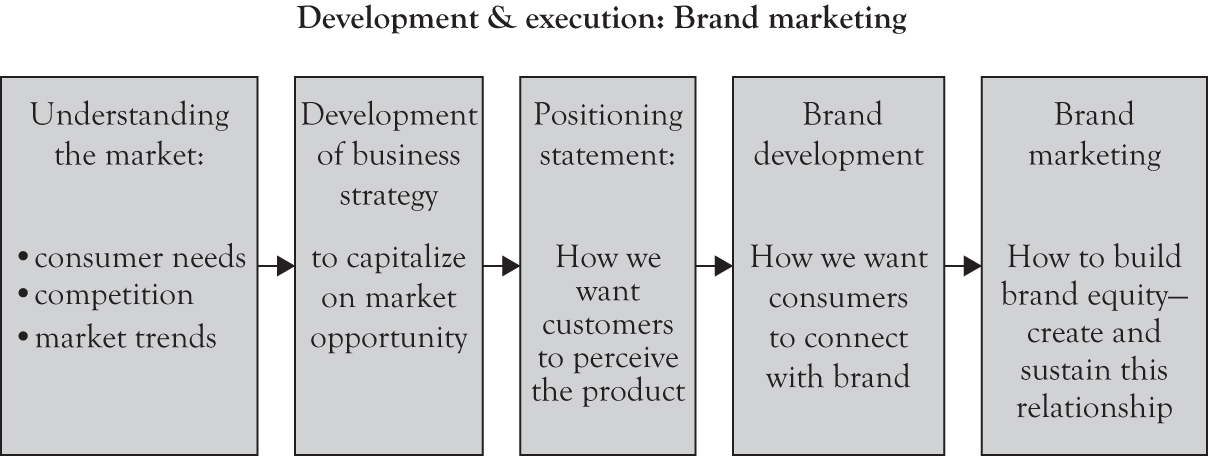

An “issue” is basically a challenge or potential problem facing a business. It reflects a current situation or hypothetical scenario in the future that is important enough to influence the success of a plan. Defining these key issues will help you understand and prioritize the prerequisites for success, often allowing you to better assess the customer acceptance of a change or improvement. In addition, issues should determine whether and what kind of market research may be warranted to resolve these questions. A simple “decision flow chart” can help a marketer design a research effort:

Brand-Related Issues to Research—Examples

Branding is about perceptions, which can make it very difficult to diagnose and reach clear conclusions. Nothing is ever black or white. And the consumer will rarely tell you directly or credibly exactly what you are looking for. Understanding key underlying positioning or brand issues usually involves extensive “trial-and-error” learning and refinements from the qualitative research diagnostics, most often focus groups or some form of one-on-one interview. The experienced marketer will gain important insights and direction using concepts and other stimuli to address fundamental brand issues such as:

• Is the benefit for the brand not relevant, too limited, or just not compelling enough?

• Degree of interest in the core idea of a positioning? Overall credibility of the idea and its support?

• Is the prime target audience profile correct, outdated, or too narrowly defined?

• Is one brand perceived by consumers as too similar to another in a company’s portfolio? If so, how should it …?

• Can I broaden the benefit or target base (e.g., with line extensions) without jeopardizing my core users?

• Is there a clear brand identity or personality in the consumer’s mind? Is this different from the competition? How?

• Is the current perception of the brand still relevant, or too old, ordinary, or boring?

• Do consumers really understand concepts or benefits that are subject to differing interpretation, such as “indulgence” or “convenience”?

• When expanding to a new market or country, can we still use the same positioning, especially if the consumer values, habits, or needs are so different? If so, how?

• Should the brand positioning change? If so, how?

If carefully crafted with discipline and research, the brand positioning should never change significantly. However, the dynamics in the marketplace can require a brand positioning to be updated from time to time—new competitive entries, technological changes, major consumer changes (e.g., different usage occasions or lifestyles). Also, a brand point of difference may be improved, or conversely perceived as obsolete or no longer so relevant. Volvo, for example, will always be known for its promise of safety, but the reality is that most other cars are now safer as well. While safety will always remain the cornerstone of its competitive positioning, Volvo has added other features or “reasons why,” such as style and comfort, to appeal to a broader audience.

Focus Groups for Brand Research

Focus group research is the most common type of qualitative research for getting feedback on new ideas in branding. Marketers annually spent over $1 billion on focus groups, according to Inside Research, an industry tracking publication. This form of research is fast and relatively inexpensive, providing marketers with a flexible format to probe for special insights and direction on new ideas. At the same time, there are risks from misusing focus groups—the results are not projectable, and individuals can be influenced by group dynamics. It is vital to use an experienced, objective moderator to control these dynamics and probe for legitimate feedback.

The recruitment is critical for preparing focus groups. At a minimum, you will want the category and brand heavy users to be well represented. Typical qualifications include specific brand usage, frequency of use, age, gender, family circumstances (e.g., with kids), etc., of the participants. Depending on the brand or topic, mixing the groups with different profiles can be risky. In developing countries, in particular, a focus group with people from different socio economic backgrounds is a sure way to curtail any open discussion. When the definition of the ideal target audience is an issue, then several groups will be required to represent the various segments of the overall audience.

Most focus groups start with a general discussion on the overall category needs, usage habits, and attitudes. It is important to not only gain a good understanding of current perceptions of your brand and the competition, but also probe deeper to identify those “hidden” problems or wishes, which can translate to valuable insights for brand building. A good moderator can transform this category discussion into a fertile source for new ideas for brand positioning. There are several methodologies that are used for ideation sessions, which can also be effective for focus groups, especially for drawing out these emotional dimensions and uncovering consumer insights. Here are some examples:

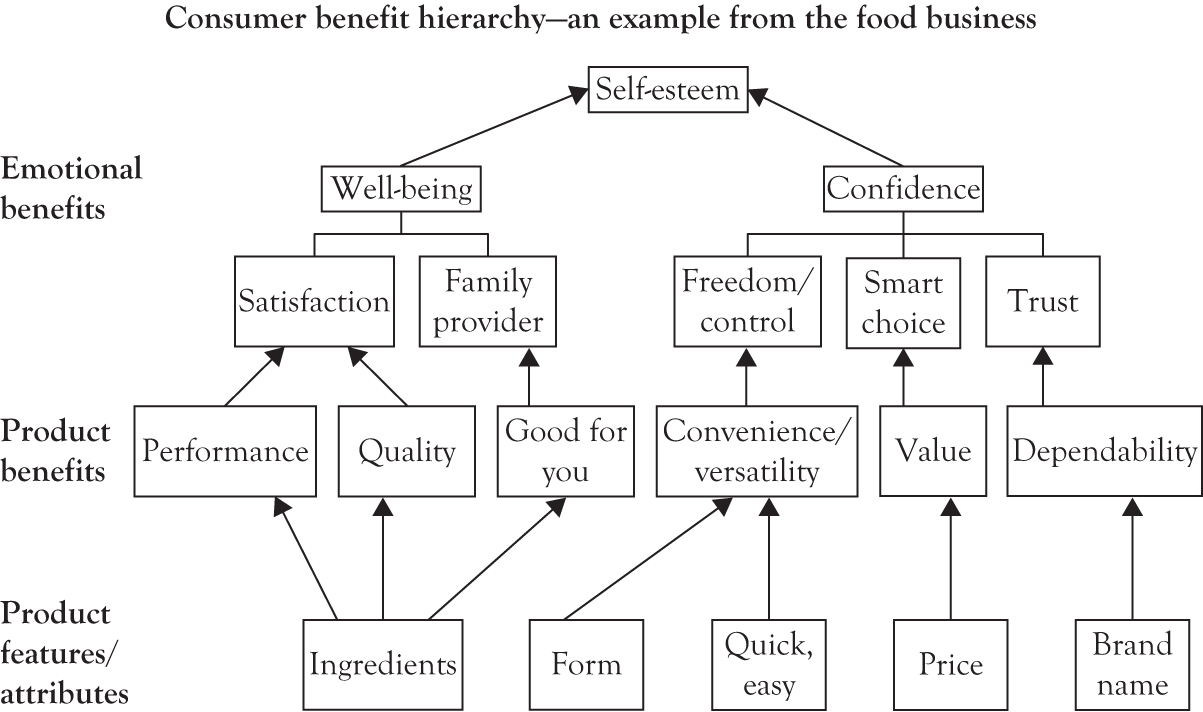

• Brand/Benefit Laddering: The purpose is to go beyond the generic benefits of a category and identify those “hot buttons” or compelling benefits that are particularly relevant to consumers. The focus group participants would be asked to “ladder back” from the more obvious functional or category benefits to then reveal the emotional benefits tied to each. These are then prioritized according to the importance to the participants, and become the basis for writing a positioning statement for the top two to three ideas or emotional benefits.

• Brand Personification: This technique is used to better understand key competition in a category, by developing descriptions that characterize the brand as a person. A full line of competitive products is shown to the participants and they are asked to think about each brand as a member of a family, and then to say which they would most likely associate with and why. Participants would also be asked to imagine each competitive brand as a person, and to think about how each person would act in a social gathering—for example, what they would wear, topic of conversation, most obvious personality qualities, and what you might like and dislike about the person. These findings are often transformed into brand archetypes, which help the marketer further understand the perceived profile of the brand versus its competitor.

• Consumer Story Completion: This approach enables participants to personalize their feelings about certain issues. They are given an open-ended story and then asked to complete the story on how each issue would be addressed. In particular, the moderator will probe to more deeply understand the needs, attitudes, and emotions toward the specific occasion for using the product, including the perceptions for how each product makes them feel. The entire group then discusses these stories. Examples of types of stories are as follows:

∘Sally noticed that this dessert wine was from Spain, so she expected it to be like _________________

∘Mary was in a gourmet wine store, searching for something special to go with the dessert for her dinner party. She chose _________________.

∘Mike buys a Sherry or Port for sipping at night, while Nick only buys brandies and liqueurs. Describe each person and why they chose what they did.

• Collages: This approach encourages consumers to express their views on brands in a nonverbal manner, by having a few participants cut out pictures from a magazine during the focus group and create a collage that describes the problem or issue for a category, or to visualize what a particular brand means to them.

After a thorough discussion of the category needs and usage habits, marketers will want to focus on the particular issues being tested. For branding research, it is common for the copy to succinctly describe each idea mounted on a concept board, which is like a rough print ad. It will have a headline that summarizes the positioning benefit, a visual that communicates the core idea, and body copy that embellishes the positioning support or “reasons why.” It is important to have some kind of stimulus to assess initial reactions and to encourage a full discussion of the overall interest, including reasons why/why not, communication of the main idea, likes/dislikes, product support, and fit with expectations for the product.

Once these ideas have been discussed, the marketer can gain a deeper understanding of the visual direction of an idea by introducing some imagery exploratory stimuli. Normally, these consist of photographs of various product usage situations or other image boards showing some support points (e.g., how a product is made, “beauty” shots that convey certain emotions). The purpose of this exercise is to determine which visual best fits each positioning concept or idea.

Examples of Typical Brand Positioning Issues/Criteria to Probe

General Category Discussion

• User profile, values, habits, and needs

• Buying habits, direct or online versus traditional retail

• Attitudes toward category issues and different situations

• Implications for family, health, social stigma

• Expectations and opinions on different product/package forms

• Perceptions and imagery of different brands in category

• Specific views on your brand and closest competitor

Consumer Response to Positioning Concepts

• Degree of interest in core idea of positioning

• Perception of relative value of a brand

• Overall credibility and relevance of the idea and its support

• Most compelling positioning elements or phrases

• Which ideas best reflect perceived strengths and expectations for the brand

• Which ideas seem inconsistent or in conflict with expectations/perceptions

• How different or special does the positioning seem versus competition

• Overall favorite positioning concepts, and why

Building an “Asset Profile” Brand Development

Following market research activities, such as a series of focus groups with full discussions of the category, the marketer will begin to see re-occurring themes of similar perceptions or responses consistently appearing in the consumer feedback. The asset profile is simply an analytical tool for structuring the perceived strengths and vulnerabilities of your brand and usually the closest competitor, based on these research findings. Distinguishing between a random, isolated observation and an immediate impression or spontaneous reaction that is frequently demonstrated by consumers can be tricky, however. These same perceptions must occur over and over in research before they can be legitimately classified as a “strength” or “vulnerability.”

The main purpose of this asset profile process is to identify those key strengths that can be leveraged for brand building, relative to competition. In particular, the relevant strengths that a marketer will want to identify for his/her brand must:

• Differentiate the brand from competition

• Favorably compare with the perceived vulnerabilities or weaknesses of the competitor

• Identify those vulnerabilities that can be overcome with improved positioning

• Lead to a proprietary or “ownable” positioning for the brand

• Enhance the perceived value of the brand over time

All these research findings are evaluated and consolidated so that the key brand benefits and vulnerabilities can be clustered under types or platforms. Several years ago focus groups were conducted to better understand the core perceptions for the Kodak brand in the United States, as a way to determine the specific strengths to build on for new line extensions:

Kodak’s Benefit Platform

|

Perceived strengths |

Perceived vulnerabilities |

|---|---|

|

Quality:

|

|

|

Simplicity:

|

|

|

Traditional:

|

|

|

Reliable:

|

|

|

Family:

|

|

|

Emotional:

|

|

The asset profile process is an excellent way to objectively check the current perceptions of a product or corporate brand, which is indeed the “reality” despite what many internal managers may think or wish. This analytical tool is also very helpful for developing the positioning of a line extension as it will provide useful direction for each element of the positioning statement:

1. Target Audience and Needs: Help define and even visualize more precisely the ideal target customer: who, profile, needs, beliefs, and values.

2. Competitive Framework: Identifying the competitors that your brand best matches up against, relative strengths, and points of difference.

3. Benefit: Defines the core idea or promise that would be the perfect fit with current perceptions, and become the strategic focus or vision for the brand.

4. Reasons Why: Distinguishes the specific strengths that could be leveraged and make this benefit promise more credible, ideally becoming a proprietary point of difference.

5. Brand Personality: Provides ideas for image qualities that will make up the brand personality.

Innovation and Idea Generation for Brand Building

In August 2011, Clay Christensen wrote in The Economist that “Innovation is today’s equivalent of the Holy Grail … and business people everywhere see it as the key to survival.”

Innovation takes many forms, but all involve creating new ideas, whether it’s the “big idea” or several tactical initiatives. Research consistently reveals that 80% of companies know that big ideas are critical to success, yet only 4% think they know how to do this (Source: “Big Ideas” by Jonne Ceserani).

Ideation has often been called “structured brainstorming,” and is a powerful technique for innovation. There are many traditional ways to get new ideas—suggestion boxes, hiring reputable business gurus, and various forms of market research, for example. However, today’s intense competition and the pressure to transform business models in our dynamic global market require more discipline and thought for effective idea generation. It’s not easy, and you have to think … a lot. As Thomas Edison described idea generation in 1929, it’s “1% inspiration and 99% perspiration.”

Bartlett and Ghoshal emphasized the third requirement—world learning and innovation—for global success in their book Managing Across Borders. They argue that this critical competency will ultimately determine the destiny of any multinational, saying “a company’s ability to innovate is rapidly becoming the primary source of competitive success.”

Creative thinking and ideation must be an ongoing and ubiquitous element of any corporate culture. This discipline of innovation is essential primarily because we are living in a dynamic marketplace worldwide, where consumer habits and attitudes are constantly changing and competition is becoming more intense and sophisticated all the time. In most reputable companies, everyone in the organization is encouraged and rewarded for coming up with new ideas for resolving certain problems, improving operating efficiencies, and/or reducing costs.

Similarly, marketers should always be vigilant of these consumer and market dynamics, identifying opportunities and insights that can lead to new ideas, and/or seeking ways to improve the positioning and execution of their current brands. The main intent of idea generation efforts is to turn needs into ideas. As a key backdrop, it starts with an update of the market and brand knowledge database and a comprehensive assessment of the current market situation and opportunities. This should involve a complete understanding of current customer needs, usage habits, attitudes, category trends, and ideally a gap analysis, and should answer the following basic questions:

• Where are we now?

• How did we get there?

• What did not work? Why not?

• What have we learned?

• How are we doing?

Product Innovation Versus Commercial Innovation

When people hear of “innovation” in a business development context, they immediately associate this initiative with the development of a new product or solving a specific problem related to a particular product or service. However, the innovation process (including ideation sessions) is often employed for other, more tactical purposes, called “commercial innovation.”

This type of innovation is used primarily to drive the growth of a business. Commercial innovation is essentially any initiative that builds on the business and brand equity without requiring a new product technology or reformulation of an existing technology. The key to a successful commercial innovation for sustainable growth is balancing risk, reward, and resources required.

Product innovation usually requires significant investment (e.g., average $100+ million per major consumer product introduction) and has a longer time horizon (2–3 years). Importantly, the success rate is still very low—only 5–10% of all new consumer products are ultimately successful. Meanwhile, commercial innovation offers several advantages over product innovation:

• Leverages existing product technology, so less investment and fewer resources are required

• Faster speed to market

• More flexible and can be localized or targeted for highly fragmented market segments

• More cost-efficient

• Historically higher ROI, net present value, and success probability

Commercial innovation almost always starts with a relevant new insight that when combined with existing approaches and technologies, creates a new business-building opportunity. The actual product or brand is the focal point of all commercial innovations that are designed to enhance the growth of the core business. Here are some typical types of commercial innovation applications that are used mainly for consumer products but are also very relevant for many B2B situations:

• Benefit reframing

• Value reframing

• Brand architecture and naming

• Partnerships and co-branding

• Distribution channels

• Merchandising and point-of-sale

• Package design

• Claims

Five Essential Steps for Successful Ideation

The ideation process is iterative, beginning with this situation analysis, initial brainstorming, researching ideas and hypotheses with consumers, refinement, more research screening, developing full concepts, more research, until finally you have some valid positioning concepts that will guide the actual product development.

To make the ideation process successful, companies must realize that an organized 1–2-day session will require a great deal of work—more before and after. It all starts at the top. Senior management must be committed to the notion of change and understand certain principles and techniques of the ideation process. Here are five critical initiatives that will improve the odds for success:

1. Know Your Problem and Possible Opportunities

Einstein once commented that understanding a problem is as important as the solution. Although many companies realize that new ideas are important, they have not fully diagnosed the real challenges they face for the future, as a first step.

Every business plan will undoubtedly identify some immediate problems and good opportunities to resolve them, but generally they won’t address the more strategic, business model issues that will determine its survival in the long run—for example, future competition, category threats, organizational changes, external trends, re-positioning their brand to meet new challenges, big potential opportunities. Understanding the current perceptions of these problems and related opportunities within the company enables management to establish a minimal threshold for creating really bold, exciting ideas that are truly new and groundbreaking.

How the problem is defined is critical. The ex-Chairman of the Michelin Group once stated that “the fact that the initial problem is badly posed is the main impediment to innovation and the growth of a company.” Interviewing key employees, analyzing their feedback, and then writing a clear, definitive problem and opportunity brief will provide optimal focus and a realistic set of objectives for an ideation session. Here are some key issues to address when formulating a problem statement, assuming a more technical problem (e.g., reliability of a system or product, often for B2B):

Situation Analysis: Background should be researched to understand original intentions, expectations, performance measurements, key assumptions, comparable systems or product problems, benefits and relevance to the customer, and other insights.

Customer Impact: Who is most at risk, levels of awareness of problem, exactly who is most worried and intensity of concern, any previous requests for fixing, current perceptions and expectations, how does failing performance affect customers and exactly who, how significant, impact on trust relationships with the company or brand, any remedial action taken to date, expected versus ideal status for the customer in future?

The Problem Itself: The dimensions of the issue, how is it diagnosed, main causes, how serious is it, whether fixable, how and where does it occur, measurement, unpredictability, quality of previous assessments, new capabilities needed to address now, any new theories, competitive experience with similar problems, category-wide solutions for similar problems from other industries, generic or specific?

Other Related Issues: Regulatory mandates and risks, dynamics between government and industry associations, public and direct customers, attitudes and expectations, safety issues, how are they measured, cost/benefit implications?

2. Preparation with Creativity—the Most Vital Phase

No ideation session will be successful without comprehensive, relevant, and participatory planning. In most companies, managers are asked to do the work of several employees today and have little time to think creatively. Often, managers come from afar without any prior preparation to just show up for an ideation session, expecting to create a big, “breakthrough innovation,” but they only produce ideas that are flat, unexciting, unrealistic, or just too general or ambitious. This is more like a random brainstorming session.

Nurturing Creativity: Innovation is the lifeblood for any industry, B2C or B2B, and creativity is the primary talent for generating new ideas. The significant market and structural changes in both the B2B and B2C worlds demand more creativity today. Most often, high levels of creativity have been associated with B2C initiatives of all types, while in B2B circles this has been focused mainly on product development. A central issue for all is whether creativity is a talent that is simply instinctive or could be developed, and how.

In 2010, IBM conducted a global survey 1 among over 1,500 CEOs, asking what will be needed to “navigate an increasingly complex world.” The most important attribute cited was “creativity” (60%). What is disconcerting about this growing need for creativity, however, is the problem cited in Newsweek’s report on “The Creativity Crisis.” 2 This summarized the results of nearly 300,000 creativity tests among children and adults over several decades, and concluded that American creativity has been declining since 1990.

Is Creativity Inherited or Learned? For centuries, conventional wisdom told us that creativity was a magical trait, a product of our genes or family history, a rare genius, and that only a select few are born “creative.” In Michael Michalko’s article on “The Seven Deadly Sins That Prevent Creative Thinking,” 3 the first sin is “we do not believe we are creative” and the second one is “we believe the myths about creativity.” Included in this type of traditional thinking is the assumption that the right brain is the source of all creativity, even though no one really has a split brain as the halves of our brain are connected by an immense structure called the corpus callosum.

In his recent book, Imagine: How Creativity Works, 4 Jonah Lehrer says these assumptions are “foolish and unproductive.” Jonah’s book argues that “innovation can not only be studied and measured, but also nurtured and encouraged.” As an example, he cites 3M, which is known for innovation. In his visits to its corporate headquarters, Jonah found employees involved in all kinds of frivolous activities, such as playing pinball or simply wandering around during their regular breaks. He observed that taking time away from a problem can help spark an insight, as relaxing activities let the mind turn inward where it can subconsciously puzzle over subtle meanings and connections in the brain. Related to this, the psychologist Joydeep Bhattacharya from the University of London observed how the brain is incredibly busy when daydreaming, which is why so many creative insights happen during warm showers.

Another example of a company culture and practice that breeds active creativity is encouraging employees to take risks, venture beyond their area of expertise, and to pursue speculative ideas. This approach has been initiated by progressive companies like Google. In particular, young people tend to be the most innovative thinkers in any field, as the “ignorance of youth comes with creative advantages,” according to Mr. Lehrer.

Why Innovation Is So Difficult, Yet So Vital: Aaron Shapiro highlighted the risks of complacency in his article, “Stop Blabbing About Innovation and Start Actually Doing It,” 5 where he argues that most companies cannot innovate because everyone is paid to maintain the status quo. “Companies strive to do one thing very well, and as efficiently as possible. Success is defined by doing the same thing you’ve always done, only better, which will lead to more sales and/or lower costs.” The result is that creativity and change are discouraged by time constraints, too many approval levels, and a culture that assigns a pink slip for any failure.

These are very basic, business model problems for a company. One option is to establish a start-up business that is kept separate from the traditional company culture and its inherent deterrents to creativity. Here are some critical requirements for this approach:

• Setting Goals: These should be specific and realistic, usually seeking a solution reflecting a detailed, relevant problem statement.

• Separation: Must be free of all bureaucracy and office politics, ideally with a location away from corporate headquarters, and a different management allowed to take quick decisions, reporting to a senior-level manager. At the same time, some cultural aspects of the core corporation should be recognized and leveraged in any new organization, which will also avoid risky antagonism or frustrating roadblocks with senior management.

• Staffing and Ample Time: Consistent with Mr. Lehrer’s suggestions, the team should be comprised of people of diverse ages, expertise, and familiarity with the company’s main business, and importantly work in a very open, spontaneous office environment.

• Freedom to Fail: The innovation team must be inspired to try new things without the risk of failure hurting their career (as Thomas Edison said, “I have not failed. I’ve just found ten thousand ways that won’t work”).

• Performance Evaluations: These should be based on the volume and quality of new ideas, not whether they ultimately succeed.

Ramping Up for an Ideation Session: It is important to change everyone’s mind-set going into an ideation session, and have them start creating new perspectives and ideas beforehand so they “hit the ground running.” Here are some specific initiatives that will help:

• Give Them a Homework Assignment: Ideally, this will encourage them to put themselves in the shoes of their target customer and focus on their perceptions, for example, if possible, interview some customers or create a diary that describes their experiences with a product or service. Filling out a relevant questionnaire on customer perceptions, major challenges and opportunities, external threats, etc., will force them to commit their time and creative thinking on paper. One exercise I often use is a questionnaire that will determine the personal brand archetype of the typical customer, with descriptions that reflect personality traits, not functional elements.

• Conduct Research: This could be a survey, some qualitative studies (focus groups?), or internet desk research on emerging trends and competition, taking a “shopping” trip and observing customer behavior first hand, studying competitive websites, talking to outside experts in an industry, reviewing appropriate blogs on key subjects, and most importantly identifying those key drivers or experiences that invoke the emotion and spirit of the customer.

• Mind Stretching Exercises: During the few days before the ideation session, special tasks will help the participants “warm up” their creative energies. Scientists at the University of Washington believe that listening to light classical music is a good way to release these creative juices. One unique approach is “forced perspective,” which encourages the participant to look at a thing in a different way. Ask them to start thinking of new ideas, even carry around a notebook to jot them down. Then let these ideas gestate and develop in their subconscious, which holds most of the emotional feelings. Challenge them to generate at least 15 new ideas in the 72 hours before the session. Ideas originate from a variety of unfocused, random situations such as the following:

∘Showering or shaving

∘Commuting to work

∘During a boring meeting

∘While reading

∘While exercising

∘In church

∘In the middle of the night

• Provide Focus: The problem/opportunity brief should be circulated beforehand, asking everyone to critique it, make suggestions, and use it as a building block for fresh perspectives. The objectives should be clear, realistic, and simple. These objectives will serve to bring the ideation discussion back to the main theme when wandering too far. These objectives should ideally be posted in front of the room where everyone can see it, as well as including them in the problem/opportunity brief. Importantly, an outside facilitator should probe the viability of these objectives with senior management to ensure that their expectations are realistic and the ideation session is designed properly. Finally, there should be a clear agenda, with enough detail to enhance the individual preparation by the participants, but with enough flexibility to be able to pursue and build on unanticipated directions and ideas.

The challenge is to convert relevant needs into new ideas or benefits. Ideation is a discipline that takes many forms, but the key is to think “out of the box” and use various stimuli to trigger new thoughts and perspectives. Idea generation can be structured to identify and build on a variety of issues and insights such as the following:

Ideas Based on a Strategic Opportunity Area

∘Overall trends in demographics, usage habits, etc.

∘New technological advances

∘New product types—even from other categories

∘Unique local cultural factors

∘Packaging innovations

Ideas Based on Category Consumers and Needs:

∘Usage habits

∘Attitudes and perceptions

∘Occasions for use

∘Buying patterns—who, when, how, where, etc.

∘New emerging category segments

∘Specific product problems or insights—not healthy, ingredients in product, sizes/portions too large or small, taste is too, … etc.

Ideas Based on Brand Strengths (from Asset Profile):

∘Image of brand personality qualities

∘Points of extreme difference versus competition

∘Appeal among different consumer types and segments

∘Brand name and logo—connotations for consumer and trade

∘Packaging features

Ideas Based on Competitive Vulnerabilities:

∘Product taste, flavor, or other features

∘Brand personality characteristics

∘Packaging

∘Trade/retail shortcomings and attitudes

∘Parentage, or lack of this

∘Origin or heritage

∘Pricing implications

∘Product attributes—ingredients, good-for-you, etc.

3. Getting the Right Mix of People

Ideally, you should strive to get creative diversity to generate a broad range of distinct ideas—that is, a cross-pollination of different thinking styles, both innovators and adapters, left and right brained, and include the select managers who will eventually be in charge of developing and implementing these ideas.

A common question is what kind of personality or creative skills should you look for when putting together an idea generation team. In general, the following are the most common traits associated with the ideal creative manager:

• Keen power of observation

• Restless curiosity

• Ability to identify issues others miss

• Talent for generating large numbers of ideas

• Persistent questioning of the norm

• Knack for seeing established structures in new ways

• High tolerance for making mistakes and taking risks

Clay Christensen from the Harvard Business School recently wrote a book The Innovator’s DNA, which lists five habits of the mind that characterize what he calls the ideal “disruptive innovator” (with examples):

• Associating: The talent for connecting seemingly unconnected things is crucial. Marc Benioff got the idea for Salesforce.com when swimming with dolphins and thinking of enterprise software through the prism of online businesses such as Amazon and eBay. Christensen estimates that business people are 35% more likely to sprout a new idea if they have lived in a foreign country.

• Questioning: Sharp innovators are constantly asking why things aren’t done differently. David Neeleman, founder of JetBlue and Azul (in Brazil), wondered why people treated airline tickets like cash, freaking out when they lost them, whereas customers could instead be given an electronic code.

• Observation: Closely related, the knack for recognizing different approaches and forms of behavior can stimulate new ideas. Corey Wride came up with the idea for Movie Mouth when working in Brazil, which uses popular films to teach a foreign language, when he noticed that the best English speakers had picked it up from film stars, not from school teachers.

• Networking: The best innovators also tend to be great networkers, hanging around venues or events where they can pick up new ideas. Michael Lazaridis came up with the idea for BlackBerry at a trade show, when someone pointed out a Coca-Cola machine that used wireless technology to signal that it needed refilling.

• Experimenting: They also like to “fiddle” with both their products and business models. A marketing manager at IKEA realized the value of self-assembly when he adapted to the task of fitting furniture into a truck after a photo shoot by taking the legs off, and a new business model was born.

4. The Ideation Session

By the time the actual 1–2-day session starts, the participants should be eager to express their thoughts and preliminary ideas. Inevitably, there will be some who view a 1–2-day session as a waste of their valuable time. This is why a convincing, relevant preparation and the shrewd choice of participants are so important. The session should be designed so that the participants have fun, too. Certain games and other “energizers” are always undervalued in ideation sessions. Research has shown that humor and laughter can release endorphins, which help people relax, improve their recall, and subsequently yield better results.

While every ideation session will be different depending on its goals, there are several common elements that should be considered:

• Professional Facilitator: Some companies are reluctant to spend money for an outside expert in these “cost-control” times, but it is critical to have a neutral and empowered professional to facilitate (but not manage) the session. Good ideas don’t come from deep analysis, but from an environment and approach that breeds openness, curiosity, novelty, fun, and risk taking. An experienced facilitator will have the tools and techniques to keep people generating ideas, even when they think they have run dry.

• Key Components for Ideation Session: Generally, the ideal number of participants should be around 8–14, comprising a mix of creativity styles and varying expertise. Having the CEO present can be risky, but if so, he/she should take a back seat or supportive role in the brainstorming efforts, generally adding a constructive perspective or insight wherever appropriate. If possible, the session should be held away from the main office in a well-lit, comfortable room (sunshine is best) with whiteboards or flipcharts and post-it notes, including one or two support personnel to record the ideas and help organize the notes on the walls, and most importantly, plenty of relevant props—for example, competitive products, benchmark analogies, examples of customer feedback or perceptions, novel packages from other industries.

• The Anatomy of a Typical Ideation Session: There are many formats for an ideation session, depending on the purpose and who will attend. When the participants have to travel, a session should be designed to last at least 2 days, usually with individual meetings before and after. Typically, an ideation session will start on a Monday afternoon with a discussion of the problem/opportunity brief, the objectives, and some mind-opening case studies and analogies to stimulate their creative energy. Then a full day of ideation on Tuesday, and Wednesday morning devoted to a summarization with refinements of some ideas, prioritization, and a follow-up game plan (conducted jointly with senior management). Another approach might involve shorter ideation sessions over several days or weeks. For example, 2–3 hours to generate an abundant collection of initial ideas (100+), subsequently organize, and cluster the ideas by type (e.g., new product or package, marketing, service oriented, strategic positioning problem solutions), and then let these preliminary ideas incubate in the participants’ subconscious for a while to digest and expand upon. An ideation workbook with these ideas defined in clusters should be circulated for review and additional thoughts or embellishments. After a few days, conduct another “upgrade” ideation session over a half day, to further refine, expand, and narrow down the list to around 60–75 good ideas, for example. This should be followed by further scrutiny, cutting, and prioritization in more upgrade sessions, ideally reducing the list to around 15 solid ideas. Within such ideation frameworks, there are other factors to consider such as the following:

∘ Building on Momentum from Preparation: An obvious starting point is to discuss the fresh perceptions and ideas that each participant brings to the ideation session.

∘ Make Ideation Ongoing: Smart companies recognize that the real value of organizing such an ideation is to change the internal culture, to add creativity to everyone’s mandate (Google employees must allocate 20% of their time for creating new ideas).

∘ Ideation for Different Goals: Traditionally, most ideation sessions are focused on new products, but more companies are using this for specific problems and also for strategic purposes—for example, different business models, new growth initiatives, re-positioning their corporate or product brands, various marketing or sales tactics, pricing alternatives to enhance perceived value.

∘ Customer Perspective: Any ideation should be shaped around current and future perceptions from their customer, making sure that all ideas would be relevant for them and competitively distinct. The use of smart market research, past or future, can be a critical building block for ideation.

∘ Think Long Term/Future: Another useful focal point is to ask what the company or product portfolio should ideally look like in 3–5 years. Within a framework of category and competitive threats, trend-building exercises are invaluable for identifying new ideas and growth opportunities, especially when the group is split up into teams.

∘ Other Exercises: There is a host of various techniques to keep the creative juices flowing, each encouraging “out-of-the-box” thinking. Assuming the participants include those who will lead the implementation, simulation exercises that involve role playing or case studies can be very effective (customized training can be combined with these endeavors, too).

∘ Building on Each Idea: Usually, the “seed” of an idea is created at first, but to make sure each can be developed to offer real value, key positioning dimensions should be added—for example, for which customer and his/her needs, the relevant benefit or promise has added value, and the key features that would make this promise credible.

5. Implementation: Making It Happen

Benjamin Franklin once said, “when you’re finished changing, you’re finished.”

At the end of the session, a thorough and realistic assessment of the viability of the ideas is crucial. Then the real challenge comes into play. In most companies, the best managers are usually overwhelmed with too many mandates and activities, so the last thing they want is another responsibility. Such an overload situation will never result in successful development or commercialization of any idea. It is up to senior management to anticipate this possible conflict and adjust accordingly. The following are some important initiatives to ensure effective implementation:

•Sustain Idea Generation/Refinement Efforts: Ideation should be ongoing. Far-sighted companies often use a special ideation session as the stimulus for establishing a corporate culture that is more focused on innovation. A new responsibility like this should have HR and senior management support, including incentives and appropriate resource allocation. Because all initial ideas require further financial and market research analysis, the idea refinement and execution stage should be well planned with a schedule of follow-up meetings and progress reports.

•Criteria for Judging Each Idea: Good ideation sessions evoke high levels of emotion, which is important for motivating a team effort, but it can sometimes obscure the harsh realities of product/service feasibility, market acceptance, and adequate financial ROI. A worksheet with criteria should be prepared before the ideation session to help gauge the true potential as these ideas are developed. For example, some sample questions are as follows:

• Does it solve a real problem—what advantage does it create?

• Is the message/image consistent with the brand?

• What are the risks in implementing the idea?

• Is the competition doing this? How is it different?

• What is the ROI? Estimated 3-year monetary payback, for example?

• What kind of further research or market testing is required?

• Is there any risk of patent infringement?

• How do we measure success?

• Developing and Committing the Best Resources: At this stage, it is prudent to review all work to date with some kind of written “idea summary” document for senior management to study. This summary should define the best ideas to determine those that are worthy of further investigation and research. Marketing, product development, R&D, and/or technical should be in agreement with this idea summary, ideally with input from other key members of the idea building team. This idea summary document should provide information that would be used for writing concepts and eventually make up a positioning statement. Typically, the following data are included:

∘ Opportunity Description: Summary of the user and usage.

∘ Core Idea Statement: Description of the compelling consumer need, the benefit, and the reason to believe.

∘ Competitive Framework/Point of Difference: The main competitors and the benefit or support element that separates it from this competition.

∘ Summary of Supporting Factors: Key feedback and how it is identified, could come from qualitative observations, brainstorming groups, sensory panel interviews, and other consumer responses.

∘ Summary of Preliminary Technical Issues: Oriented to the product feasibility and possible options.

∘ Summary of Preliminary Financial Merit: Category size, growth trends, analogous new product success stories, market share potential, etc.

∘ Timetable for Concept Development and Quantitative Screening: Summary of next steps, consisting of task and due date.

Concept Development and Testing

After the idea summary document establishes the leading ideas to build on, the next stage involves concept writing and testing. Whereas ideas are focused on the benefit that meets a compelling consumer need, concepts go further by including a technical “solution” or how the benefit promise in the idea is to be delivered (i.e., concepts add the support or “solution” for how each idea/benefit promise can be delivered). This is the “reason why” support is also essential for determining the execution or form of the product.

When you add some “flesh on the skeleton” of the initial idea for a concept, you are adding to the complexity of the hypothetical brand and product. It is essential that concept development goes through multiple refinements with consumer input. Forget the “must be perfect the first time” syndrome. There may be elements from other concepts that should be switched and/or combined, assuming the central compelling idea remains intact. This is an iterative process requiring ongoing feedback from the consumer. Initial purchase intent measurements can easily change when you introduce new variables and options in the future: pricing, positioning, new product attributes, new feature/benefit linkages, and distribution alternatives.

Focus groups are used often for refining concepts. Other qualitative research practices include customer panels, in-depth interviews, panel discussions with trade and media experts, and competitive benchmarking techniques. The main goal is to determine the viability of each concept, usually with a purchase intent measurement as the key indicator. In addition, it is important to identify those elements that drive this consumer preference, especially the benefit hierarchy links of the consumer benefits:

∘Product features/attributes—what is it?

∘Product benefits—what does it do for me?

∘Emotional benefits—how do I feel about that?

New Organizational Culture and Resources Needed

With senior management’s full support, a high-urgency development program must follow the ideation session and extended research activities. This means sufficient funding, selecting ideal HR resources (Peter Drucker stated, “you put your best people on tomorrow’s business”), and sometimes customized training.

Steve Roehm from “Strategic Innovation Insights LLC,” used to conduct workshops when he was at IBM that focused on this quest of preparing an organization for further development and implementation of new ideas. The biggest challenge, usually underestimated, was how to develop a new business model that can successfully change an organization’s culture and resources for adapting a strategic innovation. IBM encouraged its clients to re-assess its organization and develop a new business design for this task. In particular, Steve instructed senior level executives to use a “Congruence Model,” based on the book Winning Through Innovation by M. Tushman and C. Reilly, for identifying the gap between current and future resources needed for:

∘Critical tasks and processes

∘Formal organizational structure

∘People resources and skills

∘Organizational culture

Specific criteria should be established for setting goals and measuring progress, which will ultimately determine the likelihood of success in the market. Key steps for this include the following:

1. Determine the ideal target purchase intent and uniqueness scores, specify trends to be leveraged, re-examine the category size, its compounded growth rate, and competitive threats to the brand, all of which can be measured with further research.

2. Make sure the strategy fits with existing business priorities and core competencies of company, it can deliver against strategic opportunities identified in a situation analysis, it has the ability to enhance total brand value—for example, is it a new category, does it resolve a strategic portfolio or competitive gap, and can it strengthen the competitive advantage.

3. Continually assess the adequacy of current capabilities, existing equipment, the necessity of any process changes, technology within the company or industry, preliminary risks, and other resources needed.

4. When gearing up for an in-market test, set realistic profit targets, sales goals, payback period, contribution margin objectives, and cannibalization losses to be expected.

A summary of this overall innovation model for creating new ideas is as follows:

Brand Names, Logos, Symbols, and Taglines

Names—the Face of the Brand

Of all the branding elements, there is none that is more important than the brand name. It is the face of the brand, the first indicator of the brand for all awareness and communication efforts. It consciously or unconsciously creates an immediate and usually lasting impression that will shape the perception of that brand. Memorable names will generate associations, which help establish that special meaning of the brand—what it is and what it does, and create a special relationship with the customer. It actually forms the essence of the brand concept.

Today, a good brand name is even more important as it will help penetrate all the clutter that bombards us. It has been estimated that from the time we wake up to our radio alarm, to the time we fall asleep, the average person is exposed to up to 10,000 brand names, images, and messages each day. In addition, the right name will make it far easier to create a distinctive image that will become the basis for long-term value of the brand equity.

Developing memorable names with optimal connotations for a brand has become a big business. Whatever the approach used, and there are many, the same basic criteria should be used for developing a good name:

∘ Must Reflect the Positioning and Brand Personality: Examples of demonstrable names that are very advertiseable: Head & Shoulders, Master Lock, Die Hard.

∘ Different from Competition: Classic example of confusing competitive names: Goodrich and Goodyear. Too close will invite litigation, too.

∘ Descriptive, yet Avoid Becoming Generic: “Lite” beer from Miller is a good example of an unprotectable generic name.

∘ Simple, Easy to Remember, and Sounding Good: Ideally one or two syllables.

∘ Not too Confining: Don’t want to describe a specific type such as “Airbus” or “Ticketron.”

∘ International Use: The “Nova” car is the popular example of not doing your homework in Latin America (translates to “does not go”). Vicks Formula 44 is another example—“4” implies death in Japan.

∘ Avoiding: Overused names (e.g., Continental, Delta), hyphenated names (Owens-Corning), letter abbreviations (CPC, AMF, FMC, CBI), although acronyms with a certain meaning can be okay (CARE, MADD).

Naming consultants have traditionally focused on semantic associations, or the names whose parts evoke some desirable association. Today, these consultants are going beyond the hybrid versions of new words. A relatively new discipline is emerging for creating new brand names called “Phonologics,” which is used often for pharmaceutical products. The purpose is to link raw sounds of vowels and consonants to the specific meaning and emotions desired from a brand. Research by brand consultants and linguists indicate that there is a subconscious relationship between certain speech sounds and emotions, even in foreign languages, which is useful for global brands. For example, the use of “x,” “z,” and “c” all imply power and innovation. Names with these letters look good in print and people like the sound, especially physicians who feel the harder the tonality, the more efficacious the product is. Examples of pharmaceutical names with these letters include the following:

• Nexium

• Clarinex

• Celebrex

• Xanax

• Zyban

• Zithromax

This approach of “sound symbolism” does start with the brand, or what kind of image the name consultants will try to achieve with a new name. For example, the BlackBerry name fits a desired impression: “berry” suggests smallness, “b” implies ease and relaxation (e.g., won’t need a 200-page manual), the short vowels in the first two syllables suggest crispness, the alliteration conveys light heartedness, and the final “y” is a very pleasant and friendly way to end the name. Some other consonants and vowels that have connotations with specially implied meanings and emotions are as follows:

|

Letter |

Connotation or implied emotion |

|---|---|

|

k, t, p |

Crisp, quick, so daring, active, and bold (good recall), but associated with unpleasant emotions (also d & r) |

|

z |

Most active, fast and daring, yet comfortable |

|

x |

Hi-tech action, as with science fiction, cars, computers, and drugs (e.g., “X-Files,” “Matrix,” “Lexus,” Microsoft “X-Box”) |

|

v |

Also very fast, big and energetic, pleasant emotions |

|

d, g, v, z |

With vocal chords vibrating, sound larger and more luxurious than sounds with an explosion of air (t, k, f, and s) |

|

f and short e |

Evokes speed and fast (long e implies small) |

|

p, b, d, t |

Come to full stop, connotes slowness (vs. z, v, f, s) |

|

s, l |

Pleasant feelings (ss connotes “elegance”) |

|

b |

Reliability |

|

y (at end) |

Pleasant and friendly, and is why it is often found in nicknames |

The images and emotions that people associate with new names is perhaps best demonstrated in the pharmaceutical industry. Here are some examples of how the combination of the word parts and individual letters can have a particular connotation that reinforces the desired brand identity:

∘ Prozac: The letter “p” implies daring and activity and supports its “ac” ending, which suggests action. The letter “z” also implies action, or speed of recovery.

∘ Zoloft: “zo” means “life” in Greek and “loft” suggests elevation. The beginning “z” and ending “ft” are very attention getting. The letter “z” is also the highest rated for fast and active, yet comfortable.

∘ Sarafem: This comes from the angelic “seraphim,” although the ending was changed to “fem” as it is for women with severe premenstrual irritability. This also has a soothing prefix, “sara.”

∘ Viagra: Rhymes with “Niagara,” which is known for honeymoons, where water is linked to sexuality and life. The “vi” in the beginning is like “vitality” and “vigor,” while “agra” evokes “aggression.” The letter “v” also connotes speed, energy, and bigness.

∘ Cialis: The “s” sound flows gently, with a smooth “l” in the middle (has no stop consonants like “k” or “p”), so the name is pronounced in a relaxed, open way.

∘ Levitra: Comes from “elevate,” with the “le” implying masculinity (in French), and “vitra” reminiscent of “vitality.”

Over-the-counter (OTC) brands must be even more simple and memorable as the primary audience consists of average consumers, especially considering the alternative or technical name for each: Tylenol is acetaminophen, Aleve is napoxen, Amoxil is amoxicillin, and Advil is ibuprofen. The letter “l” provides a subconscious feeling of pleasant relief, and so it plays an important role in many of these successful OTC brands. Many of them end with “l”—Nyquil, Tylenol, Advil, and Clearasil.

Symbols, Logos, and Taglines

A brand’s symbol and slogan can become important assets if tied effectively to the name. Ideally, the symbol should communicate specific associations that distinguish a brand and reinforce the brand personality. Once a brand has created high awareness and positive feelings from its prior communications, the symbol or logo alone can quickly sustain this well-established impression and consumer loyalty. The brand name “Nike” is rarely advertised today because its “swoosh” symbol is so well known and powerful. And who can forget Forest Gump opening a letter on the stock performance of “some fruit company,” with the symbol on the masthead of an apple with a bite taken out of it. The red umbrella of Travelers’ is a clear reminder of how this insurance company “protects” and similarly the Rock of Gibraltar for Prudential implying strength and stability. Some other examples of symbols that connote the attributes of a brand: Mr. Clean’s muscular sailor representing the cleaner’s strength, the “good hands” of Allstate indicating personal care and competent service, and Mr. Goodwrench of GM to communicate its well-trained, professional, and friendly service.

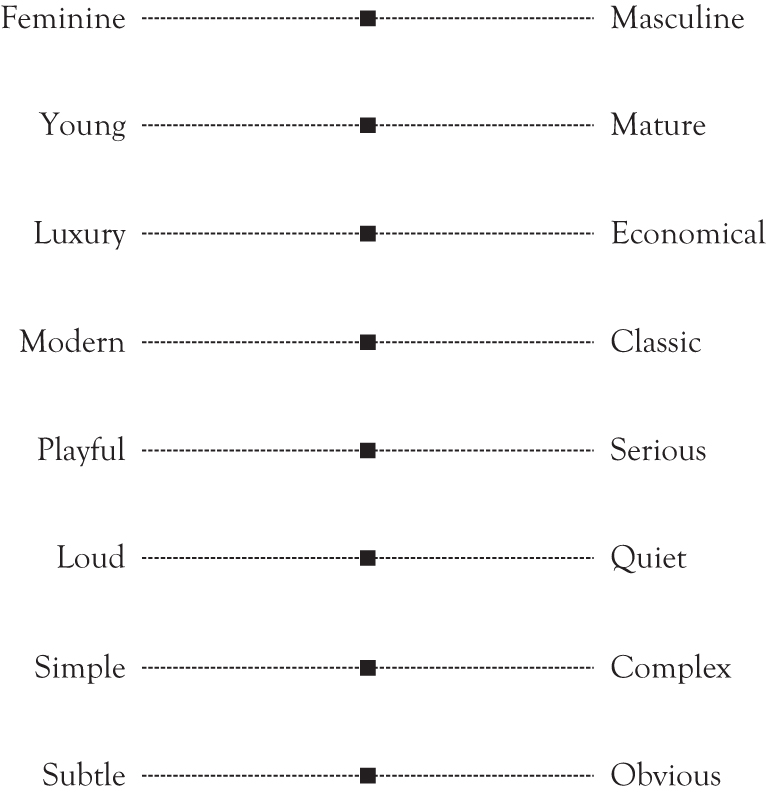

It is important to visually communicate a brand’s personality, including the emotional driver that a logo (plus all advertising, packaging, websites, and other brand graphics) should convey. For example, here are some contrasting traits that could guide a brand marketer when creating the ideal logo:

Slogans or taglines are an excellent way to sum up and reinforce a brand positioning. Why risk any confusion or failure to grasp the brand benefit from just the name and symbol when a succinct tagline can quickly capture the essence of a brand. P&G uses a tagline for almost all of its products: “Bounty is the quicker picker upper,” “Cascade. So clean it’s virtually spotless,” “Pamper the skin they’re in,” and “Dawn takes grease out of your way.” Other famous slogans include the following:

• “We try harder” (Avis)

• “Don’t leave home without it” (American Express)

• “In touch with tomorrow” (Toshiba)

• “Making it all make sense” (Microsoft)

• “Does she … or doesn’t she?” (Clairol)

• “The best a man can get” (Gillette)

• “The world’s local bank” (HSBC)

These slogans are meaningful in English, but they can backfire when literally translated in foreign tongues. The Pepsi slogan in Taiwan “Come alive with the Pepsi Generation” was translated to “Pepsi will bring your ancestors back from the dead.” Similarly, the Kentucky Fried Chicken slogan “finger-lickin’ good” came out as “eat your fingers off” in Chinese. Some taglines may have a memorable alliteration or rhyme in English (e.g., Pringle’s “once you pop, you can’t stop”), but often they simply won’t work as well in a foreign tongue.

When creating a new tagline, the following are some accepted guidelines to consider:

• Short and simple, no more than eight to nine words

• Communicate or enhance brand positioning benefit

• Paint a “word picture,” with words that are easy to remember and that can also be recited

• Original, must be meaningful, avoid clichés, not just “cute and catchy”

• Distinctive, defining customer benefits that set the brand apart from competition

• Persuasive, conveys the “big idea” you want people to know about your business

• Integrate brand name in tagline if possible—for example, P&G’s “Please don’t squeeze the Charmin.”

One issue on taglines that evokes several different viewpoints is whether and/or how often you should change it. Some feel that it should be a permanent or at least long-lasting element of the overall brand design/communication. Taglines from P&G rarely change, as they believe strongly in consistency. Other companies feel a fresh look is needed (e.g., McDonald’s third change in five years, to “I’m lovin it”), or that their current slogan is too limiting, especially when a company expands its business or services. Xerox changed their slogan for this reason, from “The Document Company” to “Technology/Document Management/Consulting,” which may be a more accurate representation of their new direction but is certainly not as memorable. In any case, the concept behind the tagline, permanent or new, should always reflect the essence of the brand, which should never change. My view: consistency and longevity should be preferred for building trustful relationships with consumers.

Ideally, a good slogan or tagline should be used to supplement the basic brand message and enhance the overall communication of the brand. Here are some examples of specific uses of brand taglines:

Creative copy to communicate benefit

•LIPITOR: “For Cholessterol” (to lower cholesterol)

•Bayer Aspirin: “Expect Wonders” (for several benefits—pain relief, anti-inflammation, heart attack prevention, etc.)

Reinforce advertising campaign dramatization

•Viagra: “Let the dance begin” (supporting TV and print ads showing couple dancing, in anticipation …)

•Gatorade: “Is it in you?” (for visualization of driven athletes sweating Gatorade out of their pores)

Go beyond benefit, for a “call-to-action” behavior

•Milk: “Got Milk” (since 1993, how milk makes your favorite foods taste so much better)

•Oreos: “Milk’s Favorite Cookie” (how milk occasions are best only with Oreos, especially for dunking)

•Aflac Insurance: “Ask about it at work” (encourages nonuser to get into supplemental insurance category)

Multiple meanings

•Tylenol: “Feel Better” (not only physically, but emotionally—that you’ve made the right decision)

•Viagra: “Love life again” (you can have a love life again, plus you can thereby love life again)

Rhythm—to make it easy to remember/play on one’s mind (use of rhyming or alliteration)

•Clean & Clear: “Clean & Clear and under Control” (use of similar “C” sounds)

•Bayer Aspirin: “Take it for pain. Take it for life” (use of parallel sound structure)

Establish an emotional connection

•DeBeers: “A Diamond is Forever” (longest running brand slogan in the world)

Brand names in slogans for advertising

• “Dirt Can’t Hide from Intensified Tide”

Double meaning with brand names/slogans

• “Volvo: For Life”

• “Visa: It’s everywhere you want to be”

• “Sleepys – for the rest of your life”

Slogans that reinforce brand’s strategic benefit

• Corona: “Change your latitude”—benefit of Mexican tropics and can escape from the humdrum of ordinary, domestic beers

• Chevy Trucks: “Like a rock”—benefit of hard-working and dependable, functionally and emotionally

Copy words/slogans to reinforce ad campaign idea

• Polaroid: “See What Develops”—demonstrates photos developing before your eyes, plus the commercial where the husband finds a sexy photo of his wife in his briefcase, enticing him to come home for lunch

• Michelin: “So much is riding on your tires”—our most precious possession (our baby) carried by its tires

Taglines that never delivered on their product/service promise

• United: “Fly the Friendly Skies”

• Chevy: “Start the Revolution”

Another important aspect for communicating a brand personality is the overall design of the name, symbol, logo, slogan, color, and graphics. The goal of any brand communication effort is to create a common, harmonious expression of that brand, which must be consistent in all customer “touch points” (i.e., everything that the customer comes into contact with). This is called “brand harmony.” Some examples of touch points that should convey the same brand imprint include the following:

•product and packaging (most important)

•all advertising and other forms of communications

•at point-of-sale (displays, collateral material at retail, etc.)

•trade show exhibits

•website layout

•all contact information—phone, fax, web URL, etc.

•all aspects of retail space

•corporate identity (annual reports, uniforms, etc.)

When developing new communication materials, there is always someone who will want to enlarge the logo, change its look, or even abbreviate the company name. The brand is more than a name or logo; it is the sum total of all previous advertising, customer service, product development, and every other aspect that touches the customer. Brand design consistency is critical because it is the face of a company or product. When you make any change to this look, you are weakening the familiarity and hence the emotional relationship the customer has developed with the brand. Even simple changes can confuse the customer and jeopardize the brand’s value. With so much clutter in the marketplace, building a consistent, synergistic theme in all marketing and sales materials will help a company break through and build long-term brand loyalty.

Ideally, every brand should evoke some kind of image or feeling—for example, contemporary, traditional, young and hip, easy-to-use, hi-tech. This same impression must be conveyed in all touch points. A good example of a company leveraging a core visual attribute is UPS and “brown.” Its advertising slogan is “What can Brown do for you” and this brand impression is dominant in all its touch points—trucks, uniforms, print ads, etc.

Most major companies have comprehensive “fact books,” which detail the precise design parameters for the company and brand name, font style, logo, color (PMS number), taglines, etc., that must be strictly followed all around the world. These fact books even define the brand associations that are most important to consumers. For example, Oreo cookies from Nabisco explain exactly what each dimension of these associations means (e.g., for taste, satisfaction, the filling, the eating experience, and the emotional well-being for the brand).

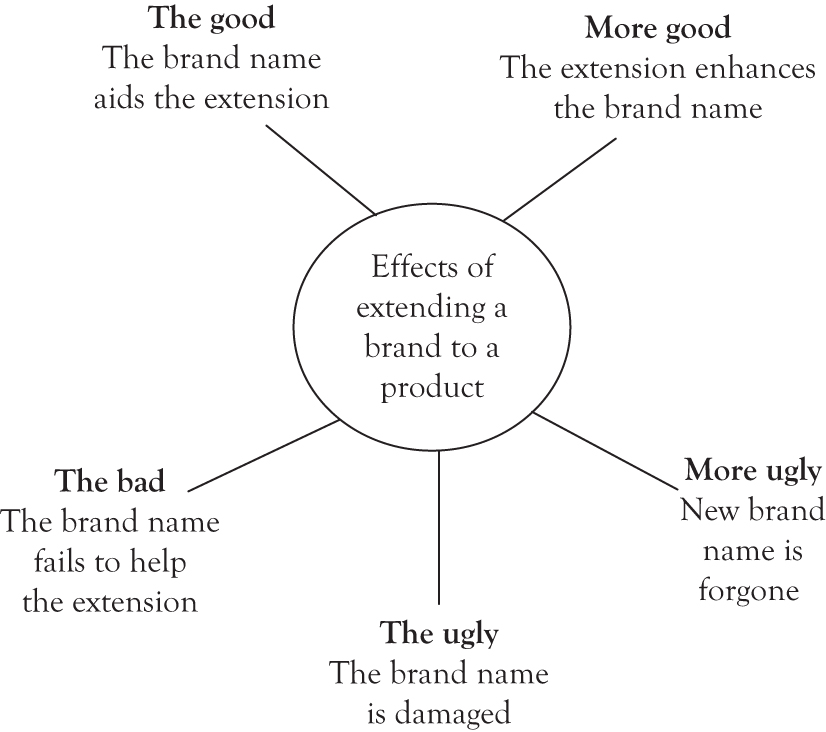

Growth from Brand/Line Extensions

Leveraging a brand to expand its product line has been the dominant approach for strategic growth in the past two decades. By far, most “new product” introductions were simply new sizes, packaging variations, new flavors, etc. One consumer survey found that 89% of these introductions were strictly “line extensions” of this nature. Only 5% involved entirely new brands, and another 6% consisted of the use of a brand name for a different type of product, generally under a licensing arrangement.

The big attraction of line extensions is the ability to leverage the brand name in a more cost-efficient way, versus introducing a new name. Normally, in consumer products the investment for introducing a new brand can cost from $100 to $200 million, and the risks for failure are significant. A new product brand makes sense only if it is truly different and offers a compelling benefit that can generate sufficient volume and hence justify the high costs of building awareness and brand equity. How it is sold also makes a difference. Selling it off the shelf at retail requires higher levels of marketing support, whereas a product sold directly by sales people or with a doctor’s recommendation (RX or prescription drugs) usually does not involve such broad and heavy communication efforts.