Chapter 2

The Positioning Statement, Emotions, and Brand Equity

A Simple Tool, but a Must for Branding

All good consumer product companies use some form of the positioning statement. This is a critical marketing tool that forces one to summarize in writing the blueprint for a brand. It should be emphasized that a positioning statement is not prepared on a whim or without an enormous effort and time commitment. It should be the culmination of exhaustive market research with consumers, a comprehensive assessment of the market potential and optimal opportunity for a brand, and a thorough analysis of the competition. While most companies have their own customized terminology and format, a positioning statement usually includes the following elements:

Target Customer and Needs

Identifying the primary target audience is perhaps the most important “first step” in marketing. It answers the critical question, “for whom?”. Often, a category requires a dual audience, or a primary and secondary segment that should be targeted. This is particularly relevant in the pharmaceutical industry, where the doctor, pharmacist, or both play such a vital role in recommending certain over-the-counter (OTC) or prescription products.

There is an understandable tendency, once a new product has been developed, to simply assume that the products’ most distinguishable attributes will become the main basis for trial and usage, especially if it reflects years of research and development. This may eventually be the case, but there is absolutely no substitute for doing the mandatory research that will help define exactly the profile of the target prospect; what his/her needs, values, and desires are; and whether/how a product or service can make a credible and deliverable promise that addresses these needs. Understanding these target audience needs, wants, or expectations requires an extensive examination of the following:

•Current usage habits—where, when, by whom, other circumstances, including competition.

•Intensity of all these needs and wants, in order of priority.

•Perceptions about and attitudes to your product and the competition.

•Relevance of these needs, plus expectations for delivering on promises.

•Trends and changes in consumers’ preferences or tastes.

•Overall brand potential, indicated by the incidence of a need or problem, the intensity, and the number of people with similar needs.

In research, consumers will initially express their problems or needs in a rational way, or what they want and how their needs should be fulfilled. These are called functional or physical needs. For example, I want to stop coughing, or I want the aches and pains in my back to go away. These rational desires are identified “through the head,” and address what consumers want a product to do for them in terms of performance. At a minimum, a product must be able to deliver on any of the promises to address these basic functional, conscious needs.

By probing and using other research techniques, experienced marketers will take these needs one step further and discern how consumers want to feel, which reflects their emotional needs (“through the heart”). Identifying these intangible feelings, often called the “sweet spot,” should be the real goal of any positioning research, including how consumers actually express their wish for ultimate satisfaction. Typical examples of desired feelings include peace of mind, assurance, sense of trust, feeling safe, and so on.

An example of a success story built on emotional needs is Starbucks. They recognized an emerging trend where more consumers wanted to drink authentic, robust coffee, and were even willing to experiment with more exotic, creative coffee beverages. However, this basic functional need was not be enough to make Starbucks really stand out. They stepped up to address an emotional dimension of this functional customer need, the desire for a special experience. Starbucks positioned their coffee shops as a distinct “coffee-supplemented” experience, where customers could enjoy the “chic European-style” ambience in addition to strong coffee. There were also special features in the original Starbucks café environment that offered a distinctive yet relevant appeal to the unique psyche and desires (classical music, internet access, unique packaging, etc.) of its target customers, who tended to be more urbane, proactive, upscale, sophisticated, and just wanted to “chill out” with their strong coffee in this enticing setting.

Focusing on such emotional passions is also the best way to develop a meaningful expression of the brand personality, because the brand’s relationship with the consumer will be much stronger and more motivating when it is based on these feelings. Shelly Lazarus, the current president of Ogilvy & Mather, eloquently described this emotion-based relationship in Pfizer’s 2001 annual report:

Brands are complex. They are created out of main points of contact with the customer. It’s not just product functions and features that drive the brand relationship. Rather, it’s a myriad of interactions—some commercial and pre-ordained, some ambient and unpredictable … The best companies today understand that it’s essential to build a relationship between their brand and their customers—one that takes into consideration every interaction. To do this requires a full understanding of what customers feel about the brand and what they expect.

Good marketing requires ongoing vigilance of these customer wants, as needs are constantly evolving and perceptions change with these market dynamics and the influence of competitive actions. This means maintaining a steady dialog with consumers, usually with qualitative research such as focus groups, one-on-one interviews, or online chat rooms. It is important to add a fresh perspective whenever possible. Marketers who have held the same responsibilities for a long time may not easily notice subtle trends and changes, so adding new marketing talent to participate in research, examining different product categories, and exploring markets abroad can be vital for identifying new ideas. In addition, conducting quantitative tests or tracking studies to capture signs of emerging attitudes and usage habits will help marketers keep their brand marketing fresh and relevant.

There are many dimensions to a consumer need, and it requires astute intuition, an open mind, and various types of creativity to understand the implications of each need. The biggest challenge is to gain a perspective on the relative importance of these different needs, and determine how one can distinguish their brand from the competition and deliver against these top priority needs. Identifying the physical needs is easier, and in some cases may be enough. However, by probing and laddering back on the hierarchy of consumer perceptions, one can gain some unique insights that could help dimensionalize a brand positioning. SnackWell’s cookies from Nabisco did a good job of this by combining two different needs in its positioning: the basic snacking indulgence with the emerging desire for dietary health.

Assessing these consumer needs within the context of the overall market trends and opportunities will help a brand positioning seem more innovative and distinct in several ways:

Creating or Extending a Category: Probably the most visible recent example is the erectile dysfunction category. The first entry—Pfizer’s Viagra—shaped this segment, but the market potential proved so vast that subsequent entries such as Cialis (Eli Lilly) and Levitra (Bayer/GSK) have been able to carve out significant businesses and extend the category. Similarly, Procter & Gamble’s Pampers played the same role as Viagra by creating an entirely new market segment (i.e., the disposable diaper business) years ago.

Gaining Ownership: With clever research and steady advertising support, a brand can develop and then own a dimension of a basic need in a way that establishes an impenetrable niche for a category. P&G marketers heard from consumers that bad breath was most prominent in the morning, so they coined the expression “morning breath” for their Scope Mouthwash advertising (now copyrighted). Another example is Oreo which owns their “signature” dunking the cookie in milk.

Expanding a Target Group: It is important to always be on the lookout for new ways to leverage an established brand need or usage by fine-tuning a positioning, even with a new product, for a peripheral target group. The core of Neutrogena’s legacy has always been associated with its translucent amber bar of soap. Johnson & Johnson’s research showed that teenagers were familiar with and admired their soap purchased and used by mothers, but they felt it wasn’t enough for their acne problems. So Neutrogena introduced a similar product, an amber “Acne-Prone Skin Bar” for teens, which met their needs for gentle cleaning and, more importantly, controlling acne breakout.

Creating a New Use: In the medical business, there is a steady supply of independent research that can occasionally turn up a new opportunity for an established brand. A classic example is Bayer, when clinical studies revealed the benefits of pure aspirin in helping to prevent heart attacks. There is always a risk of diluting your base positioning when touting a completely different benefit, but Bayer’s advertising kept its primary use in focus with its selling line, “Powerful Pain Relief … And So Much More.”

Competitive Framework

This answers the question “against whom” from the customer’s standpoint. The importance of identifying your main competition cannot be overstated. We are living in a very competitive world, and a brand will never succeed unless it offers a better option in the consumer’s mind. By defining the competitive substitutes available for your customer, the marketer can also establish the primary sources of revenue for his/her brand and guide marketing programs accordingly.

In-depth research will be needed to learn all about the competitive brands, primarily from the consumer’s perspective, including their perceptions of the benefits, usage (loyalty, frequency, potential limitations, etc.), the brand image or reputation, price/value, product quality, performance, packaging, and all other strengths and weaknesses. Ideally, the positioning must somehow convince the target customer that its brand is indeed different and even superior to the primary competition.

Positioning a brand against the right set of competitors can help create the best potential image. Consumer perceptions are changing all the time, especially with the introduction of new products and re-positioning efforts by competition.

Taking an example from the food industry, consumers’ attitudes toward and usage of salty snacks have become far more complex. Around 1990, purchases of salty snacks were based more on expected performance and benefits, such as a sense of indulgence, health (better for you) options, and availability of complements like salsa dip.

These changing market conditions opened the door for new products and line extensions, with a positioning that reflected both product form and taste expectations. Different snack product forms are now available for each expectation, giving manufacturers more options for the competitive frame of reference positioning.

There are other competitive framework considerations for positioning a brand so that its optimal potential is realized. Much depends on a brand’s life cycle stage, the relevance and extent of its consumer appeal, and how competitively distinct it is. Some worthwhile positioning tasks include:

Developing a “Specialty” Image: When a brand does not have a major competitive edge and wants to avoid a “me-too” image, it can focus on its primary strength or usage base. Excedrin re-positioned itself to “specialize” in a large volume segment of the pain reliever category, to become “the world’s headache medicine of choice.”

Separating Yourself from the Crowd: In a very competitive segment such as the pain reliever category, it often makes sense to emphasize a particular point of difference, even if it is not the main benefit of a brand. By focusing on the fact that it does not cause an upset stomach, Tylenol with its acetaminophen formula further differentiated itself from its main competitors Advil, Bayer, and Aleve.

Comparing Yourself to the Category Leader: Brands that want to quickly establish an image of high quality and gain immediate acceptability will refer to a leading brand (often called the “gold standard”) when discussing product attributes. Examples of such competitive frameworks include Minute Maid Frozen Orange comparing itself to the real orange flavor and taste of Tropicana’s Pure Premium ready-to-serve orange juice, the Pepsi challenge to the world leader, Coca-Cola, and even Honda describing how the all-terrain maneuverability of its new four-wheel Passport SUV is comparable to the ultimate in performance, the Porsche 911.

Expanding the Competitive Framework: When the focused positioning of brands becomes well established, a brand can sometimes enlarge its potential by adapting a broader definition for its competitive framework: Boston Market building on its solid reputation as a fast food chicken restaurant chain to become known more for its “fast food home-cooked meals,” and Ensure expanding its niche as a hospital supplement to a line of nutritional, everyday supplements.

How a brand is categorized in relation to its competition also has implications for in-store shelf placement and merchandising. If the perception or net impression of the positioning is rather special or proprietary compared with its main competitor, then the product should be placed next to this other product. If the brand is strong and can claim a broader range of competition, then there may be additional point-of-purchase placements at retail that could expand trial. For example, referring to Oreo as a sweet snack and not just a chocolate-based cookie may encourage retailers to stock Oreo in more than one section of the store.

Benefit or Promise

This should describe the single, most meaningful promise that can be offered to the prime prospect, which would make it seem special and different from the identified competition. The benefit should answer the basic question, “what’s in it for me?” It is not what the product does, but what it does for the consumer—how it resolves his/her problem and ideally makes the consumer feel. The benefit is really a promise of something that adds value and addresses a relevant need or desire of the target customer. Only the consumer can really answer these questions of relevance, including whether the benefit should be positioned as a functional or emotional one.

This third element of the positioning statement—benefits—follows (1) the target customer and needs and (2) the competitive framework simply because the first two elements generally define the optimal benefit for a brand. Success will be attained only if a benefit can effectively address a particular need or desire of the primary target customer in a way that seems different from the competition. This is not an easy task, however. It will require a great deal of smart research and creativity to determine exactly how the benefit can be truly meaningful, appealing, and different. Some critical considerations for this analysis are outlined below.

Types of Needs/Benefits: Earlier we discussed physical and emotional needs. Understanding the nature of these needs, especially how compelling and special they are, will help you define the desired benefit at different sequential levels:

•Product Benefits: Simply identifying the main functions or what a product or service does vis-à-vis the basic physical or functional needs. For example, Tide Detergent cleans clothes, gets out dirt, and removes stains.

•Customer Benefits: Looking at the implications of this function from the customer perspective, what it means to the customer, or what it does for him/her. In the case of Tide, it keeps clothes cleaner longer, they’re softer and more comfortable, and they need fewer washes.

•Emotional Benefits: Usually this represents the most compelling reason for choosing a brand, the way to the customer’s heart. It’s all about feelings. This is a benefit of the highest order and will most likely be the best building block for that trusting relationship between the brand and the customer. Using Tide as an example again, the emotional “pay-off” or benefit is the feeling of pride in your clean clothes, how this will reflect on you and members of your family, plus the basic confidence of making a good impression.

Identifying the emotional “hot button” and being able to articulate it in a meaningful consumer language is probably the biggest challenge for marketers. Branding is about perceptions, so research should focus on how consumers construe their own problems and views, what insights can be picked up and then tested with further research, and finally expressing a dimension of the benefit that will strike this emotional chord with the target customer.

In problem-oriented categories such as the pharmaceutical business, the desired feeling one can experience on solving the problem is often the ultimate “clincher” for trying a product. Marketing for the prescription brand Fosamax, for example, focused on the inherent fear of osteoporosis with the theme “Fight Your Fear.” Print ads had headlines like “Since I found out about my osteoporosis, I’ve been afraid to walk to my mailbox when it rains.” The copy explained how Fosamax rebuilds bone and bone strength (product benefit) so the consumer can do what he/she wants (customer benefit) and, most importantly, restores his/her confidence that will help overcome this fear (emotional benefit).

One should not ignore the potential of a customer benefit when a new product can offer a real breakthrough advantage, however. When Polaroid was first introduced, its instant development process was so revolutionary that emphasis on anything but this product benefit detracted from the key selling point and point of difference.

EffectiveBrands, a global marketing consultancy, extends these types of benefits to include “purposeful benefits,” especially for big global brands. At the bottom of the benefit ladder is “functional benefits.” HTC is an example of a brand that promises fast download speeds, but no emotional benefit, and hence it is difficult to relate to the HTC brand as a person. Stella Artois leverages its 600-year-old heritage to interact with consumers on the best ways to pour and drink its beer, which creates a credible relationship and an emotional, trustful experience.

At the top of the benefit ladder is “purposeful benefits,” which offer a societal purpose even beyond a firm’s “corporate social responsibility.” This type of benefit should relate to the essence of the brand and leverage its integrity to make the world a better place. Examples of brands that offer such a purposeful benefit are:

•Dove: Stands for real beauty

•The Body Shop: Against animal cruelty

•FedEx: Sustainability connecting people and places

Consistent with this view of “purposeful benefits,” Marc Pritchard, the Global Marketing and Brand Building Officer at P&G, at a recent world conference talked about building brands to serve a higher purpose that will in turn produce more sustainable business results. Marc commented that “we must change from marketing to consumers to serving our consumers.” He added that today’s consumers are asking for more from brands, “they want to help the world, not just themselves, and as a result will choose those brands that share their value beliefs.”

Competitive Benchmarking: The perception of a brand is often shaped by how it stacks up against a familiar competitor, so selecting the rival brand for this comparison can be crucial. There is a natural tendency for manufacturers to immediately stereotype or categorize a brand, typically as a result of a market segmentation analysis. The retailer will think this way too, because his mind focuses on product sections of a store. But the consumer will invariably view a brand’s position, or at least their expectations for its performance, in a different light.

A few years ago, my company did some research in the United States for a new dessert wine from southern Spain. These wines were certainly drunk and perceived as very popular dessert wines in Spain, but dessert wine drinkers in the United States, to our surprise, did not view this Spanish product as a dessert wine at all, as it was much darker, heavier, with higher alcohol levels compared with other dessert wines in America. With further research we realized that the profile of the best potential target user should instead be those who drank liqueurs, not dessert wines per se. The product’s final positioning was as a “wine liqueur,” a conclusion reached only by re-defining the target audience profile and hence the competitive framework for this re-positioned brand.

A useful analytical tool to diagnose these perceptions and expectations versus competition is the Brand Asset Profile. After fully researching a given category and identifying the underlying customer needs and main competitors recognized by the customer, research determines the most important, prevalent perceptions of the strengths and vulnerabilities for your brand versus the competition. The objective is to select and leverage the perceived strength that would be most compelling for positioning a brand, which should ideally address a burning customer need and capitalize on the perceived vulnerability of the brand’s main competitor.

Single or Multiple Benefits? This is a very complex issue for many manufacturers. From a strategic and communication standpoint, the greater the focus, the more successful you will be in conveying a message, distinguishing yourself from the competition, and establishing an image of a “specialty” product. But this raises other practical and business questions. Are the expectations too high and can you deliver on a single-minded promise that implies “the best?” Is the business potential sufficient to justify such a narrow focus? Do you offer a benefit that you “own” and cannot be duplicated easily by the competition?

Excedrin took this route when it positioned itself as “The Headache Medicine.” The highly saturated, mature analgesics category was an environment where a niche-oriented positioning made the most practical sense for Excedrin. By reaching out primarily to consumers with severe headaches, implicitly the kind that could not be relieved as effectively by competition, Excedrin created a specialty image among these sufferers as the strongest, most powerful remedy for this problem.

Positioning an “umbrella brand” that is powerful and offers more than one benefit can give the consumer the impression of added value, that he/she will be getting more for their money. Successful brands can introduce line extensions that address multiple needs, especially when the related benefits are perceived as an extension of the core strength of the brand. Tylenol PM is positioned as a combination of an analgesic and a sleep aid. This appeals to the same basic target group, because users view a good night’s sleep as another way to help relieve their pain. Tylenol can get away with this multiple benefit strategy because of its strong position in the market and ample budgets to communicate these related benefits.

Some brands have been developed on a multiple benefit platform mainly because of their traditional usage and the attitudes of consumers. Perhaps, the best example is Arm & Hammer Baking Soda from Church & Dwight, where I spent time as head of New Products. This was a sleepy brand, yet was used in almost every household in the United States for over a century. In the early 1970s, however, focus groups revealed that many housewives put it in their refrigerator to absorb odors. This led to a new positioning, backed by new advertising, and sales exploded. More research showed how Arm & Hammer had long been considered the ultimate multiuse product, with housewives using it for everything from poison ivy relief and bathing to putting out fires and cleaning teeth.

After advertising its new positioning for absorbing odors in refrigerators, Church & Dwight started developing a wide array of different products under the Arm & Hammer brand name, stretching itself to such diverse and unrelated uses that the trust for the Arm & Hammer brand showed signs of being undermined. We re-grouped and asked ourselves how far this brand could be stretched before jeopardizing its inherent integrity. By re-examining all these uses and looking for common themes, we concluded that the usage of Arm & Hammer Baking Soda, as an ingredient in line extensions or re-positioned uses of the base product, had a higher chance of success if it remained in the categories of cleaning and deodorizing. Fortunately, these two basic usage categories were very diverse and provided ample opportunities for a steady stream of new products for years to come.

Features and Benefits: While this comparison is certainly not new, the exercise can be very helpful in encouraging people to take a step beyond the obvious functional aspects of a product or service, and answer the question of what it actually does for the customer. Such features are facts, or generally refer to the attributes of a product. They can be important if they relate to how to satisfy a customer need, and are more appropriate for convincing someone that the promise or benefit is indeed credible (i.e., part of the “reasons why” in the positioning statement).

Benefits are about the significance of these features, or how it adds value or offers some kind of “gain” for the customer. As such, they must be deemed highly relevant for the target customer, ideally with an emotional element. As an example, a toothpaste may have special ingredients that contain bleach and whiten your teeth (feature and its function), but importantly it makes the customer feel more attractive (the emotional benefit).

Ideally, the benefit should be a selling idea that is distinct, or at least perceived to be different from the competition, although this is becoming increasingly difficult in reality. This is why more companies are focusing on the ultimate brand personality, together with a well-positioned benefit and support, to create a net impression of being special and standing out. Good research and experienced analysis will often reveal new consumer insights that become the basis for a novel or different benefit. Some key questions or criteria for identifying an optimal benefit for a brand positioning include the following:

1.Can the benefit be modified for different target segments of the audience?

2.How meaningful, compelling, or important is the benefit?

3.Is it truly unique, or at least perceived this way, compared to the competition or the category?

4.Does the benefit fit a market “gap” or address a certain consumer dissatisfaction in a competitive area?

5.Is the benefit proprietary, patentable, ownable, or preemptive? Can the competition copy it?

6.What is most relevant and would generate the most interest, the functional or emotional benefit?

7.Are there other secondary benefits worth identifying, or will this dilute the impact of being single minded and focused?

8.Can you satisfactorily deliver on the promised benefit and adequately meet the customer’s expectations?

Over time, successful brands have reinforced a single-minded benefit repeatedly to a point where today they practically own a particular promise. Here are some examples of brands that are immediately associated with a specific benefit, to the extent that they “own” it:

|

Brand |

Category |

“Owned benefit” |

|---|---|---|

|

Volvo |

Cars |

Safety |

|

Domino’s Pizza |

Pizza/fast food |

Delivery |

|

Wal-Mart |

Retail |

Low prices |

|

Southwest Airlines |

Airlines |

Low prices |

|

FedEx |

Shipping |

Overnight delivery |

|

Dell |

Computers |

Buy direct |

|

Maytag |

Appliances |

Reliability |

|

Coke |

Beverages |

Original/heritage |

|

Pepsi |

Beverages |

Younger generation |

|

Listerine |

Mouthwash |

Kills germs |

|

Lysol |

Cleaning/bathroom |

Kills germs |

|

Crest |

Toothpaste |

Fights cavities |

|

Colgate |

Toothpaste |

Whitening |

|

Aquafresh |

Toothpaste |

Tartar control |

|

Close-Up |

Toothpaste |

Fresher breath |

Reasons Why (or Reasons to Believe)

These are often the most important factors for differentiating and selecting a particular brand. These support points basically legitimize the benefit, make the promise credible, and help to clarify how it is different from competition. Marketers frequently refer to this as the “Reason to Believe” (RTB).

While the benefit should focus on what a product does for the consumer, the reality is that the desired impression for most consumer products does not vary significantly. Most deal with some dimension of product quality or customer satisfaction, and so it is a real challenge to define a benefit that is entirely unique in itself. What is needed to make a brand appear distinctive and ideally proprietary is the combination of the benefit and relevant support. The specific “reasons why” or “permission-to-believe” points will depend on the consumer needs and the nature of the benefit, and generally fall into four types:

Logical Explanation: This is anything that helps explain how a product works or solves a problem, especially if it is a proprietary process. For example, Fosamax refers to how it builds bones and gets you moving again to help you fight osteoporosis and its debilitating effects.

Hard Evidence: A common rationale used for OTC brands involves the special design features or ingredients in the formulation as proof of performance. Often, the favorable results are communicated in the form of a picture or graphic illustration. For example, Coors Beer claims it is the only beer made with “Rocky Mountain Spring Water,” which makes it more refreshing.

Outside Recommendations: Any kind of endorsement from a professional organization, independent study, or even a celebrity spokesman can help build credibility for the basic promises. Tylenol’s proprietary claim of “hospital recommended” has become a classic. Michael Jordan is still one of the most respected spokesmen, and he was a key reason for Nike’s success.

Brand Track Record and Heritage: Reference to a brand’s origin and/or proven success in the past can be a compelling RTB in a brand’s promise. Michelin tires have a strong reputation for high quality, reinforced by a very emotional visual—a baby in a tire slot—and the tagline reminder, “because so much is riding on your tires.” This “reason why” has established Michelin as the brand of choice for anxious, safety-conscious parents of young children. Other brands refer to their source to leverage memorable images associated with a specific place: Evian from the Alps, Godiva from Belgium, and Jack Daniels from the Tennessee Mountains. Many countries have developed a reputation of strength in certain product areas, and some companies have effectively leveraged this heritage:

∘Japan: electronics (Sony) and automobiles (Sony, Nissan, Honda, Toyota, and Mitsubishi)

∘Germany: cars (BMW, Mercedes-Benz, Audi, VW

∘France: perfumes (Chanel), wines, and fashion clothes

∘Ireland: crystal (Waterford) and linen

∘England: china (Wedgwood), wool

∘Switzerland: watches, cheese, banking services

∘Italy: leather, shoes, pasta, wine

∘Russia: vodka, fur

∘Middle East: carpets, oil

∘Mexico: silver, crafts, beer (Corona)

∘Colombia: coffee

∘Australia: eggs, wool

Focus and simplicity are critical for making a long-lasting, positive impression in consumers’ minds. All too often, the product-oriented mentality is preoccupied with so many novel features of a product, and is insistent on listing all these attributes as the “reasons why.” This desire must be controlled, because a brand positioning is stronger when it is single minded and succinct. Sometimes related product features can be integrated and communicated using one analogous benchmark. For example, Reach toothbrush had several distinctive features that supported the benefit of cavity prevention—angled neck, higher and lower bristles, and compact head. J&J wrapped up these subselling points with the encompassing expression “like a dental instrument,” a simple notion that made its positioning for cavity prevention even more powerful.

Another way to reinforce a brand’s benefit/promise is through co-branding. However, this will only work when the other brand shares the same type and level of perceived quality, and there is no risk of brand dilution or sales erosion of each business. Häagen-Dazs is well known for its super-premium ice cream, but the brand is all about the emotional experience: “provides personal, unadulterated pleasure, which starts in the mind (anticipation), travels through the mouth and ends up in the mind (satisfaction).” To further dimensionalize the brand and add interest in their frozen novelties, Häagen-Dazs teamed up with Pepperidge Farm to offer super-premium ice cream sandwiches. This co-branding effort leveraged the strong reputation for premium quality of two nonconflicting brands to create a synergistic, competitively unique brand proposition.

The Brand Essence—Its “Personality”

The personality or character of a brand is a manifestation of the positioning. Whereas the positioning is stated in business or strategic terminology, the brand personality enriches the positioning and gives it a life. It uses adjectives and analogies that make it sound more like a person or a memorable experience.

The brand character describes who the brand is as a personage. The brand should not be described as a “thing”—product, service, or organization. Instead, using language that describes the relevant personality traits will enable you to create an image or brand identity that generates an impression that is much easier for consumers to relate to, feel comfortable with, and remember in a positive light.

A positioning is not the same as a brand. Positioning provides more details on how to rationally describe a product or service in terms of the target customer needs, the physical attributes or “reasons why,” and the differences from competition. The brand personality captures the essence or inner soul of what a brand should mean to consumers on an emotional or nonrational level. This brand essence transcends the physical attributes of the product/service and does not reference competition (neither the “best” nor “better than”). Importantly, this inner brand personality or “DNA” of the brand endures over time, never changing, even when marketed in foreign cultures. It is the constant face of the brand to the consumer.

Conversely, other elements of the positioning may be adjusted to address changes in the marketplace—competitive threats, emerging consumer habits, new innovations, and different target audience segments and their needs and cultural values. However, any modifications to the positioning should be rare and kept to a minimum, and never alter the brand essence. Here are some examples:

Kraft’s Philadelphia Cream Cheese

Brand Essence: “My daily trip to paradise”

Positioning: “For consumers with full, busy lives, Philadelphia is the brand of cream cheese that provides a little reward every day because of its unique indulgent taste and texture”

Coca-Cola

Brand Essence: “Refreshes the mind, body and spirit”

Positioning: “For consumers looking for refreshment, Coke is the brand of refreshment beverage that provides a lift to the body and spirit because of its unique taste, carbonation, and conviviality”

The contrast of brand image between Coke and Pepsi shows how two very similar beverages make a very different impression. Coke, the market leader, uses a classic number one brand strategy. It is representative of a category leadership philosophy—steady, consistent, almost stodgy with no risk-taking moves, and always conservative—making only slight refinements (except for its blunder with “Classic Coke”) to ensure that it keeps this position. Coke’s brand image and ad campaigns are filled with “Americana” associations such as baseball and apple pie.

Pepsi crafted its brand personality to strike a marked difference from Coke. As the number two cola brand, it is much more pioneering, risk-taking, innovative, and vivacious—reminiscent of the famous Avis “We try Harder” campaign against the category leader, Hertz. Pepsi took aim directly at the heaviest soft drink user segment, the youth of America. With personality traits that include “fun, active, and adventuresome,” it created the memorable “Pepsi Generation” campaign. Pepsi’s proprietary brand personality offers such a strong emotional and contagious appeal that it is not only endeared by today’s youth but also embraced by all who think and feel young.

Here are some other examples of the “brand essence” for famous brands:

|

• Nike |

Bringing inspiration to every athlete |

|

• Starbucks |

Rewarding every day moments |

|

• Hallmark |

Cared sharing |

|

• Disney |

Fun family entertainment |

|

• Nature Conservancy |

Saving great places |

|

• McDonald’s |

Fast foods served with home values |

|

• Anheuser-Busch |

Adding to life’s enjoyment |

|

• UPS |

We enable global commerce |

|

• Microsoft Windows |

Advancing everyday accomplishments |

|

• ESPN |

There is no such thing as too much sports |

|

• Accenture |

Innovation delivered |

|

• AT&T |

Your world delivered |

|

• Malibu Rum |

Exotic easy-going fun |

|

• Visit Scotland |

The natural wonder of northern Europe |

|

• Mercedes-Benz |

Engineering excellence |

|

• BMW |

Driving excellence |

|

• Pepsi |

Youthful independence |

|

• Suave |

Smart beauty |

|

• Dove |

Real beauty |

|

• Pyrex |

Inspiring confidence in the kitchen |

Using Analogies to Help Define Brands

The specific description for this succinct brand essence is not always easy to develop. The brand personality evolves from a great deal of research on the customer, the competition, and the market, so it is natural to have divergent views on what this inner brand soul should consist of. A common tactic is to use analogies that will help characterize a brand. Familiar benchmarks such as celebrities, animals, cars, and magazines can help dimensionalize a brand, stimulating new insights on various personality traits. These benchmarks will also ultimately help to communicate the full personality make-up to the creative people and other outside suppliers who must execute this brand positioning with new advertising, packaging design, public relations, promotions, and so on.

As a first step, select some of the more obvious personality traits that you think would fit the positioning. Then start thinking of different analogies. You can pick a famous person like Harrison Ford, Winston Churchill, Britney Spears, or Barack Obama who have the same traits and values as the brand. Or take a well-defined profession, such as a doctor, policeman, athlete, or scientist, which has a certain stereotyped image that reflects the character of a brand. Maybe an animal like an elephant, tiger, mouse, or gorilla would be a better fit. You could take this line of analogous thinking one step further by imagining what this person would wear and talk about at a party. This thought process opens the mind and helps crystallize the imagined personality of a brand.

The use of analogous benchmarks with recognizable personalities or images can be very effective when it describes a noteworthy contrast, especially when comparing a brand to another competitor. For example:

•David Bowie versus Pavarotti

•Meryl Streep versus Madonna

•Tom Hanks versus Hulk Hogan

•A lion versus a pussycat

•A duck versus an eagle

•A paper cup versus a crystal goblet

Other Ways to Distinguish a Brand Personality

A common challenge is to describe a brand personality in very basic terms, ideally using the language of average people, plus plenty of examples, to minimize any misunderstanding by outside creative functions and even internal ones such as sales people. These descriptors should be more unique to articulate your personality and to bring a brand to life, and not overuse words like “trust” or “leader.” For example:

•Using One Word: For example, “Irreverent” for Doritos brand, later used for its line extension “Cool Ranch.” Other examples of brands with a single-word focus that helps to visualize their band personality include:

∘Volvo—safety

∘BMW—sporty

∘Mercedes—prestige

∘Heinz (ketchup)—thick

∘FedEx—overnight

•Comparison: A defining adjective to favorably juxtapose its brand personality to a competitor:

∘Virgin Airlines being “cheeky” (impudent, yet fun) versus British Airways being “smug”

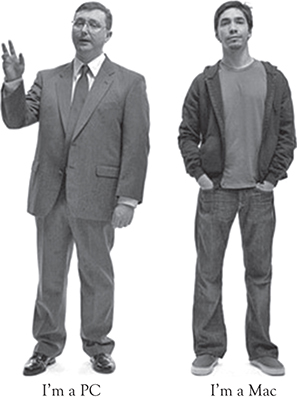

∘An Apple Mac being casual, cool, and self-assured versus the PC character as stuffy, overly-anxious, and fidgety (very well communicated in Apple’s “I’m a Mac” TV ad campaign—see http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C5z0Ia5jDt4)

•Expression of Feeling: Like the “thought bubble” in comics, describing how you want your user to feel about the brand as a person. For example, to describe Charles Schwab—“Here’s a straight shooter, someone who never has hidden agendas or ulterior motives—the only one not requiring a poker face…”

•When at a Party: Describe what music/drinks would be appropriate when your brand shows up at a party. For example (often used in focus groups):

∘Wal-Mart—country western, mixed with patriotic songs for a “down-home” block partier, drinking Busch beer

∘Target—as the “whatever” convivial partier, alternative music, drinking cherry kamikazes

•Fit in Another Category: Identifying the optimal “home” for a brand. For example, which retailer would be the best fit for a particular special skin care brand (a method often used in research):

∘Abercrombie & Fitch

∘Banana Republic

∘The Gap

∘Hugo Boss

∘Talbot’s

Common Problems and Challenges With Today’s Brands

The pursuit of “brand distinctiveness” is never easy. So many brand marketers tend to use words that are over used or just too general. Smart research and creativity are critical for going beyond the norm and selecting terms that are more specific and vibrant. For example, some common, vague emotional descriptors include: “trust,” “peace of mind,” “dependable,” “empowerment,” and “caring.”

The reality is that such brand personality descriptors represent only the threshold for many categories, often called “cost-of-entry” terminology. Brands competing in certain categories must at least convey an impression that active consumers expect at a minimum:

|

• Pharmaceuticals |

“Trust” |

|

• Telecommunications |

“Empowerment” |

|

• Whiskey |

“Status” |

|

• Cleaning |

“Caring” |

Other common mistakes include inadequate research that doesn’t go in-depth to probe the minds and hearts of consumers, not including any key emotions in the positioning statement or strategy, or simply making promises that represent wishful thinking, with no chance of delivering. Instead, marketers have to be disciplined to go beyond these common “directional emotions” when articulating a brand personality profile, to reflect varying levels of the emotional intensity, to use basic consumer language, and to create multi-dimensional touch points so that emotional connections at least reach the subconscious part of the brain. Only by applying smart research and creativity can the marketer differentiate the brand more clearly from competition and develop proprietary, memorable expressions and analogies.

Brand Archetypes

In their 1999 book The Hero and the Outlaw: Building Extraordinary Brands Through the Power of Archetypes, Margaret Mark and Carol Pearson define a variety of stereotypes to aid this brand description task:

The Innocent:

•Wholesome, pure

•Forgiving, trusting, honest

•Happy, optimistic, enjoy simple pleasures

The Explorer (or “Seeker”):

•Searcher, seeker, adventurous, restless, desire excitement

•Independent, self-directed, self-sufficient

•Value freedom

The Sage:

•Thinker, philosopher, reflective

•Expert, advisor, teacher

•Confident, in-control, self-contained, credible

The Hero (or “Warrior”):

•Warrior, competitive, aggressive, winner

•Principled, idealist, challenges “wrongs,” improves the world

•Proud, brave, courageous, sacrifices for greater good

The Outlaw (or “Destroyer”):

•Rebellious, shocking, outrageous, disruptive

•Fearful, powerful

•Counter cultural, revolutionary, liberated

The Magician:

•Shaman, healer, spiritual, holistic, intuitive

•Values magical moments and special rituals

•Catalyst for change, charismatic

The Regular Guy/Gal (or “Orphan”):

•Not pretentious, straight shooter, people oriented

•Reliable, dependable, practical, down to earth

•Values routines, predictability, the status quo, traditional

The Lover:

•Seeks true love, intimacy, sensuality

•Passionate, sexy, seductive, erotic

•Sees pleasure to indulge, follows emotions

The Jester:

•Clown, jester, trickster

•Playful, takes things lightly, creates a little fun/chaos

•Impulsive, spontaneous, lives in the moment

The Caregiver:

•Altruistic, selfless

•Nurturing, compassionate, empathetic

•Supportive, generous

The Creator:

•Innovative, imaginative, artistic

•Experimental, willing to take risks

•Ambitious, desire to turn ideas into reality

The Ruler:

•Manager, organizer, takes charge attitude

•Efficient, productive

•Confident, responsible, role model

These prototypes are admittedly subjective, but they do help by categorizing various personality traits with a descriptive label. The authors, Mark and Pearson, mention several celebrities, companies, and product brands that share qualities of these archetypes. In addition, when discussing these archetypes in my NYU branding course, I always ask the students to think of actual people or brands that may fit some of these stereotypes. Here are some noteworthy examples, from my students and the book, that can further dimensionalize these descriptions and “add some flesh to the bone”:

•The Innocent: Doris Day, Tom Hanks, Forest Gump, Shirley Temple, Disney, Breyers Ice Cream, Ronald McDonald, Baskin Robbins

•The Explorer: Huckleberry Finn, Anita Roddick (founder—The Body Shop), Charles Lindberg, Earnest Shackleton, Jeep, Starbucks

•The Sage: Oprah Winfrey, Walter Cronkite, Gandolph (Lord of the Rings), CNN, NPR, Intel, HP, NY Times, MIT, Harvard, Mayo Clinic

•The Hero: John Wayne, John Glenn, JFK, MLK, Nelson Mandela, Colin Powell, Braveheart (with Mel Gibson), Nike, FedEx, Red Cross, Olympics

•The Outlaw: Robin Hood, John Lennon, James Dean, Howard Stern, Jack Nicholson, Maria Calles, Muhammad Ali, Harley Davidson, Apple, MTV

•The Magician: Harry Potter, Yoda (Star Wars), Mary Poppins, Dannon Yogurt, MasterCard (priceless ad campaign), Weight Watchers

•Regular Guy/Girl: Cal Ripken, Woody Guthrie, Hoosiers (movie), Ben & Jerry’s, Saturn (car), Avis, Visa

•The Lover: Clark Gable, Cary Grant, Elizabeth Taylor, Sophia Loren, Cinderella, Casablanca, Revlon, Victoria’s Secret, Godiva

•The Jester: Charlie Chaplin, Steve Martin, Mae West, Jay Leno, Marx Brothers, M&M’s, Snickers

•The Caregiver: Princess Diana, Florence Nightingale, Mother Teresa, Bob Hope, Campbell’s Soup, GE, Coca-Cola, James Stewart in Wonderful Life

•The Creator: Pablo Picasso, Georgia O’Keeffe, Martha Stewart, Crayola, Sherwin-Williams, William Sonoma, Sesame Street

•The Ruler: Ralph Lauren, Microsoft, American Express, CitiBank, IRS, The White House, Cadillac

The authors explain these archetypes using historical myths, analogies, and beliefs, supplemented by examples of current brands throughout their book. Market researchers often refer to these archetypes when analyzing perceptions by consumers of different brands. For example, if the findings indicate that the archetypes for two close competitors are the same, it raises a “red flag” that the client’s brand image should be modified to appear more distinct.

Marketers find such archetypes helpful when defining their brand personality. Such detailed archetype descriptions create a sharper image for all communications initiatives. Using such prototypes can go a long way to charge up the creative juices and to apply this personification to all strategic positioning elements in a way that relates to the inherent desires of the primary target user. Here are some corporate brand images reflecting these archetypes:

1.Coca-Cola—The Innocent

2.Microsoft—The Ruler

3.IBM—The Sage, with a Jester component (from the old advertising campaign with Charlie Chaplin)

4.GE—The Caregiver (or Ruler)

5.Nokia—The Explorer

6.Intel—The Sage

7.Disney—The Innocent

8.Ford—The Hero (trucks/cars) and Explorer (SUVs)

9.McDonald’s—The Innocent

10.AT&T—The Caregiver

11.Marlboro—The Creator

12.Mercedes—The Ruler

The End Result: The Full Positioning Statement

The final positioning statement may be deceptively simple, yet the research and analysis that shape this summary can be exhaustive. But it is all worth it. The brand positioning is the heart of all marketing. It is the main tool for developing and then judging all brand communications, whether it involves advertising, personal selling, or a simple business card. Here is an example of one of the largest consumer brands, P&G’s Tide, the leader in detergents:

For Target Consumer and Needs: Moms with active children and husbands … who have heavy-duty cleaning needs and want to keep their clothes and their families looking their best

Brand: Tide is the brand of choice among…

Competitive Framework: … laundry care detergent products, that …

Benefit: … is best for your clothes (cleaning, protecting fabrics, etc.) and you, because …

Reason Why: … (a) it has a special formulation with heavy-duty cleaners (e.g., grease-releasers), special fabric protectors (e.g., color guard), and (b) it is endorsed by authoritative sources

Brand Personality: Tide is strong (like a rock), traditional, dependable, commanding, yet practical

The Brand Pyramid

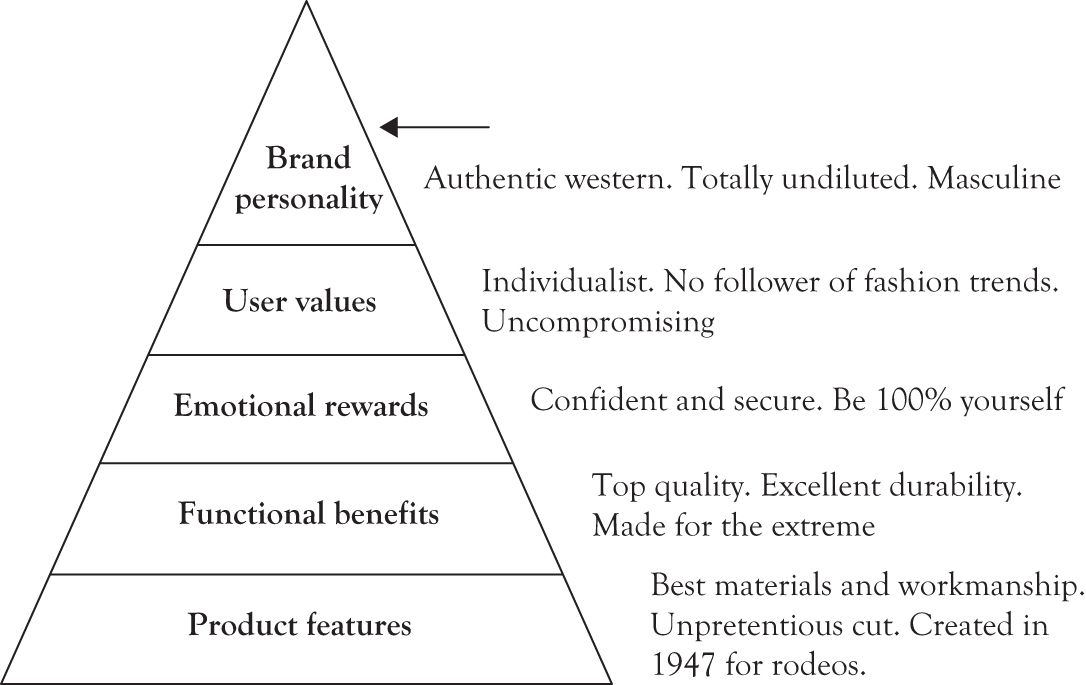

Another positioning tool is the brand pyramid, developed by Larry Light at BBDO several years ago. This is particularly useful for focusing on the emotional benefits and the brand personality. It defines the essence of the brand by connecting the rational position to the emotional framework. It starts at the bottom by identifying the product features, then moves up to highlight the functional and emotional benefits, then the user values, and finally brand personality at the peak. Here is how this positioning tool is used to define the Wrangler brand (in the United Kingdom):

Other Brand Positioning Statement Formats

Many companies use positioning statements that closely resemble the basic format described in this book, but with slightly different or additional elements. For example, Nabisco includes an important aspect that is critical for its extremely competitive categories, “A Leverageable Point of Difference,” which identifies a specific feature that distinguishes its brand from the competition. This point of difference for Oreo’s positioning is its “superbly delicious taste and fun eating ritual.” Unilever adds even more components to its positioning format—for example, insights, values & personality, and discriminators—as shown in the figure below.

A Strategic Challenge: How to Make a Positioning Seem Different?

With the advancement of performance capabilities for so many products, plus the stricter regulations on claims, it has become difficult to create a brand impression that is truly distinct. This basically involves transitioning from getting the big or “right” idea to getting the idea right. This is a strategic challenge. Here are some common strategies that have effectively differentiated well-known brands when the actual differences are minimal:

1.Leadership Position: This is perhaps the most powerful way to distinguish a brand, supplemented by its sales, technology, or performance credentials. For example:

a.Heinz owns ketchup

b.Xerox as the original copier

c.Hershey’s as the chocolate leader

d.Campbell’s dominates soups

2.Heritage: Highlighting the unique history of a brand will make people feel more secure in their choice, for a brand that is more emotionally trusted. For example:

a.Steinway: “The instrument of the immortals”

b.Cross Pens: “Flawless classics since 1846”

c.Coca-Cola: The “original”

3.Specialist: Creating a perception of an “expert” in a particular category (usually retail) or activity—for example, retailers like The Limited, Victoria’s Secret, Crate & Barrel, and Banana Republic.

4.Endorsement: People often want some kind of affirmation of their selection, called “preference positioning,” which indicates their tendency to want to “join the bandwagon” for greater confidence. Examples include:

a.Tylenol: The pain reliever hospitals prefer

b.Nike: The choice of famous athletes like Michael Jordan and Tiger Woods

c.Lexus: Highest ratings on customer satisfaction (J.D. Power)

5.Pricing: Extremely low- or high-end price points can become a meaningful differentiator. Wal-Mart and Southwest Airlines at the low end, and Häagen-Dazs Ice Cream at the premium end.

6.Distribution: A distinctive channel of distribution can be another way to separate a brand from the crowd. For example:

a.Avon: As the primary door-to-door brand

b.L’eggs Pantyhose: Sold using unique display stands in various retail outlets

c.Timex: As the first watch available extensively in drug stores

d.Dell: Selling computers directly online

The Emotional Side of Branding

People with successful relationships have developed over time a strong bond built on shared values and emotions that keeps them together. So it is with brands. Marketers must think of a brand as a person who could provide a relevant, satisfying experience. Ultimately, it is this emotional bonding that will lead to solid brand loyalty and the optimum—strong brand equity.

In theory, one should examine the marketplace to identify new opportunities that will then drive the product development process. The reality in business, however, is that most companies are either developing new products concurrent with this review of the market or start with a new product innovation and then seek a home for it in the market. This approach naturally makes one focus on the specific product attributes and how they may be useful for the consumer.

The big challenge for marketers is to remove themselves from this “manufacturer” mentality and put themselves in the shoes of the customer. This is not always easy. Imagine a brand manager, after extensive research with consumers, telling a brilliant scientist in R&D that their latest creation or advancement is not perceived as relevant or appealing to the customer. Or maybe a completely new way of describing this new product is the only way to generate any enthusiasm and interest by the consumer.

The relatively simple task is to explain what such product advances may do for the consumer. The more difficult part is to convince the consumer that he/she will actually feel a lot different once they use it. Yet getting consumers emotionally attached to a brand is what it will usually take to be a success in the marketplace.

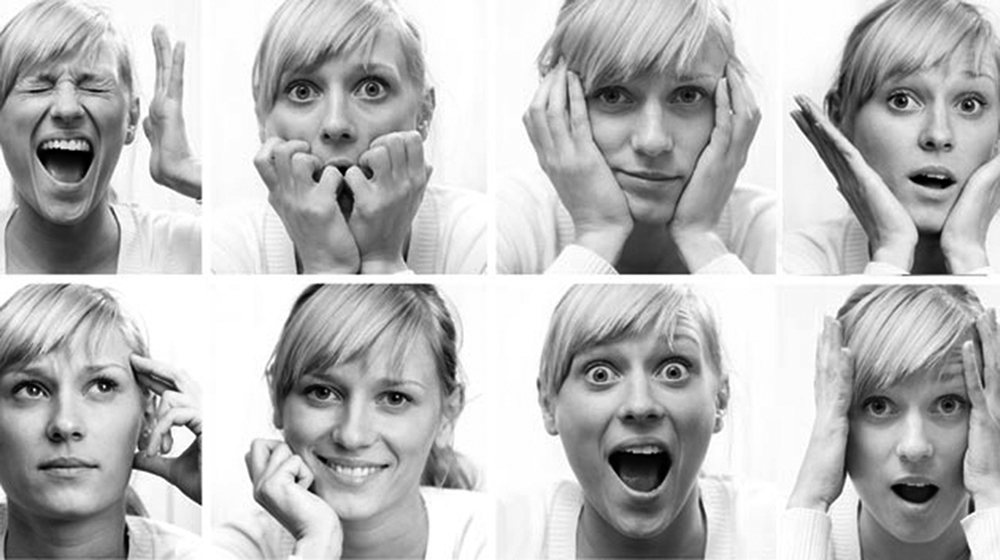

In research, it is important to look for natural emotional reactions to a concept, advertising, or package, as these will usually be more revealing and truthful for any kind of emotional assessment. For example:

Emotions and Behavior

Discoveries in the field of neuroscience have had a major impact on branding in recent years. It started in 1943 with Dr. Maslov’s famous paper on the “Theory of Human Motivations,” in which he concludes that pure emotions fulfill the ultimate need for “self-actualization”:

This revelation was followed by other conclusions from noteworthy neuroscientists on how emotions, not cognitive thinking, have the greatest influence on behavior and decision making. And marketing is essentially all about changing people’s behavior and convincing them to make a purchase decision. Here are some quotes that confirm the importance of emotions, for example:

The essential difference between emotion and reason is that emotion leads to action while reason leads to conclusions.

John Caine (2000)

The wiring of the brain favors emotion—the communications from the emotional to the rational are stronger than the other way around.

Joseph LaDoux (1996)

Over 80% of thought, emotions and learning occurs in the unconscious mind.

Professor Demasio (1999)

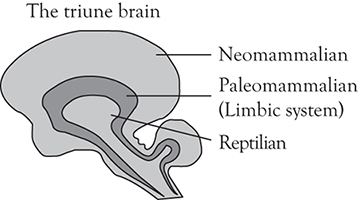

Much of Demasio’s thinking was based on a theory by Paul MacLean in the 1960s on the Triune Brain model, which explains how the human brain has evolved. Essentially, this theory explains that we don’t have one brain, but three. These are all layered on top of each other and were developed during different stages of evolution:

1.The Old Brain (Reptilian): Controls survival behavior and autonomous functions such as heart beats, digestion, movement, and breathing.

2.The Midbrain: Known as the limbic system, this is the primary seat for emotions, memories, and attention (i.e., the unconscious).

3.The New Brain: This is the neocortex, the logical part of the brain that involves rational thoughts, thinking skills, language, and speech processing.

According to this theory, we are only fully conscious of our new brain, the neocortex. By contrast, the unconscious or midbrain helps you determine what you should pay attention to with your conscious brain. This means that our decision-making behavior is greatly influenced by this unconscious brain. And it is incredibly efficient. Neuroscientists have estimated that our five senses receive 11 million pieces of information every second, with our conscious brain only processing around 40 pieces.

This theory, however accurate the amount of information absorbed, at least underscores the importance of including emotional benefits in a brand positioning, as well as all the touch points when marketing that brand. In the area of graphic design, there is a standard guideline on what communication elements have the most impact on this subconscious part of the brain—the “communications hierarchy.”

This communication hierarchy is particularly helpful when developing all the execution aspects of marketing to visually communicate a brand’s positioning and personality (e.g., logos, packaging, advertising, websites, brochures).

Seeking Consumer Insights

In this fiercely competitive world, marketers are digging deeper into consumer minds to identify worthwhile voids or issues that will help them leverage their brands. What they are looking for is a distinct or new “consumer insight,” usually a problem or challenge that the consumer is not even initially aware of. Such insights are revealed only after dogged prodding in research by experienced, intuitive marketers. Research must focus on the problems or wishes of heavy users in a given category, to try to uncover feelings that are not readily apparent to anyone.

A consumer insight can be defined as a deeply held belief or behavioral pattern that relates to the most important problems or needs in a category—the “hidden” or real hopes of people who use a particular product or service. Most consumer insights are expressed in three different ways:

•As a weakness or shortcoming of competition

•As an obstacle that consumers identify for not using your brand

•A compelling belief or opinion about a category that is not yet recognized.

Discovering relevant consumer insights requires imagination, interpretation, and intuition. You must keep an open mind to be able to “read between the lines” during customer research. Because these underlying attitudes are not obvious, it also takes constant probing. And most importantly, one should recognize that consumer perceptions or opinions are usually more revealing and important than what you think is true.

The Process for Identifying Consumer Insights

1.Available Research: Start by re-examining all current data—your “Brand Knowledge” book, supplemental information from the internet—collect data from syndicated sources, and review all past qualitative and quantitative in-house research.

2.New Perspective: Take a fresh view and focus on the heavy users in the category, starting with a review of the demographics and psychographics. Then generate as many hypotheses as possible on new or unfulfilled needs, beliefs, or behaviors to create potential concept ideas.

3.Explore in Research: Get topline reactions to the most promising concepts in qualitative research (e.g., focus groups, one-on-one interviews, ethnography, or on-site observations), to get some sense of relative interest. Most important, use these concepts to stimulate extensive discussion and probing on consumer attitudes and usage habits, to identify new insights.

4.Continue Research: Ongoing research is critical to really understand whether/how these preliminary insights (and concepts) are shared and viewed as truly relevant, extensive, and compelling. Furthermore, learn how consumers talk about these issues, and continue to seek out the most captivating and meaningful expressions to describe these insights and concepts. You will know when you have found a powerful insight (a) when you can offer a benefit and/or a “reason why” that capitalizes on it, and (b) when it is different from competition and you can deliver on its promise. More research will be needed to verify that the associated benefit or supporting RTB is truly meaningful and shared by enough consumers. Ideally, the new insight will be so novel that you can develop a proprietary claim or benefit that you can actually own. Finally, the new insight and related benefit/support must complement the current positioning and brand personality.

Here is an example of how P&G identified a new insight that led to the re-formulation and re-positioning of Tide years ago, a consumer complaining in focus groups using words like:

the kids really get their clothes dirty. I have to wash so often I actually wear their clothes out. So while I can’t afford to keep on buying new clothes, I am willing to pay more for a detergent that not only cleans, but also keeps clothes from fading or fraying.

This view was actually an obstacle among cost-conscious consumers for not using a premium-priced detergent like Tide—it simply wasn’t superior enough at cleaning clothes to warrant its premium price. Discovering this consumer insight, however, led the R&D labs at P&G to develop a new formulation with special degreasers and fabric softeners, so they could offer a new, more compelling benefit: “Tide gets out the toughest dirt while keeping clothes from fading or fraying from so much washing. So clothes don’t just look cleaner; they stay newer looking longer…wash after wash.” Importantly, this new positioning claim struck the consumer’s “hot button” or emotional “sweet spot” and resurrected the Tide brand.

Consumer Insights for Emotional Branding

Identifying and defining a compelling consumer insight that is shared by many consumers is only half the battle. Translating this into a relevant brand positioning with a heartfelt emotional dimension is the other major challenge for marketers. Many categories—premium foods, beverages, services—focus almost exclusively on the emotional rationale for using a particular product.

McDonald’s is a perfect example of emotional branding. When you think of McDonald’s, most people immediately associate it with its product or service attributes such as its hamburgers and quick service as its “reason for being.” Focusing on these “product benefits” will mean a value proposition for McDonald’s as offering convenience-oriented eaters fast meals at competitive prices.

Fortunately, McDonald’s has gone beyond these obvious physical functions to brand itself in an emotional way as the ultimate fun experience primarily for families with kids. They have spelled out this target prospect in great detail to create an actionable psychographic profile: “with strong wholesome values, seeking to enjoy the visit and meal, sharing the food and experience, and who want reliable quality and like tasty food at reasonable prices.” With this target definition as its starting point, McDonald’s positioning statement reads:

For: families with kids (primarily) who want quick, tasty meals and a fun experience, Brand/Competitive Framework: McDonald’s is the brand of choice among family oriented fast food restaurants, that Benefit: provides a fun time experience for kids and their family (the top priority), because Reasons Why: it offers (1) fast, reliable, cheerful, and efficient service; (2) food that is tasty, with reasonable pricing/good value, popular (e.g., hamburgers and fries) and consistent quality; and (3) an environment that is clean, same all over, safe, fun (McDonald’s Magic), and family oriented. Brand Personality: Like a trusted friend—reliable, friendly, wants to share everything with you, makes you happy, provides opportunity for a “special” time together, wholesome, genuine, honest, and always there for you.

Importantly, this positioning is consistent with the company’s overall vision and mission statement, which are also defined with experiential overtones:

Corporate Vision: “to be the world’s best quick service restaurant experience”

Mission Statement: “provide outstanding quality, service, cleanliness and value, so that we make every customer in every restaurant smile,” or put in a more direct way, get the customer satisfied as fast as possible, and to leave just as fast with a happy face

Satisfaction is an emotion that every service business seeks, but how they achieve this will determine how special the brand will become in the minds and hearts of category consumers. For McDonald’s, memorable communications and distinctive brand associations have shaped its brand personality and legacy like no other. In the past 15 years, its advertising slogans have changed but they all communicate the consistent emotional brand soul of McDonald’s:

“You deserve a break today”

“We love to see you smile”

“I’m lovin’ it” (current)

Consumer insights can be discovered in all forms of research; sometimes these findings can be used to reinforce a current brand personality built on an emotional image. In some countries, for example, automobiles are marketed as an analogous tool of sexual conquest. The type of car one drives can also say a lot about who he/she is and how he/she expects to be treated. According to Professor Werner Hagstotz, an expert in automobile marketing at the School of Applied Sciences in Pforzheim, “for Germans, the car is a unique symbol of identity. It’s like a bottle of wine for a Frenchman.”

So you can imagine the delight for BMW when they learned about the research results from the German magazine Men’s Car, which surveyed 2,253 drivers between 20 and 50 years of age about their sexual habits. The BMW brand is positioned as the ultimate status symbol, especially for active professionals. These survey results added a new dimension to this brand identity when it revealed that BMW owners allegedly have sex more often than any other car owner, an average of 2.2 times a week, whereas Porsche owners have sex least often, 1.4 times a week.

Types of “Feelings”

Numerous studies have tried to identify and measure the effect of brand advertising on emotional feelings (such as Burke & Edell 1989; Russo & Stephens 1990; Stayman & Aaker 1988; and Goodstein, Edell and Moore 1990). All these feelings were segmented and listed under four types: upbeat feelings, warm feelings, negative feelings, and uneasy feelings. Although much of this may be arbitrary, the following table does provide a useful perspective on the significant variety of different emotions that may be associated with brand personalities:

|

Upbeat feelings |

Warm feelings |

Uneasy feelings |

Negative feelings |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Active |

Affectionate |

Afraid |

Bored |

|

Alive |

Calm |

Anxious |

Critical |

|

Amused |

Emotional |

Concerned |

Defiant |

|

Attentive |

Hopeful |

Contemplative |

Disinterested |

|

Attractive |

Kind |

Depressed |

Dubious |

|

Carefree |

Moved |

Edgy |

Dull |

|

Cheerful |

Peaceful |

Pensive |

Suspicious |

|

Delighted |

Warmhearted |

Regretful |

|

|

Elated |

|

Sad |

|

|

Energetic |

|

Tense |

|

|

Happy |

|

Troubled |

|

|

Humorous |

|

Uncomfortable |

|

|

Independent |

|

Uneasy |

|

|

Industrious |

|

Worried |

|

|

Inspired |

|

|

|

|

Interested |

|

|

|

|

Joyous |

|

|

|

|

Lighthearted |

|

|

|

|

Playful |

|

|

|

|

Pleased |

|

|

|

|

Proud |

|

|

|

|

Satisfied |

|

|

|

|

Stimulated |

|

|

|

|

Strong |

|

|

|

Robert Plutchik, Professor Emeritus at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York and a renowned authority on human emotions, has written a book on this subject of emotional relationships, Emotions and Life: Perspectives from Psychology, Biology and Evolution. His theory is that there are eight basic emotions that serve as the building blocks for all human emotions:

•Joy

•Trust

•Fear

•Surprise

•Sadness

•Disgust

•Anger

•Anticipation

Some market research firms such as AcuPOLL in the United States use these same criteria to measure the persuasiveness of advertising (and the brand), which reflects the ability of the advertising to motivate, appeal, and ultimately make the emotional connection with consumers. AcuPOLL uses a proprietary series of questions, which they call “unarticulated emotional elicitation,” to measure these results and also uncover the reasons behind the various emotional scores.

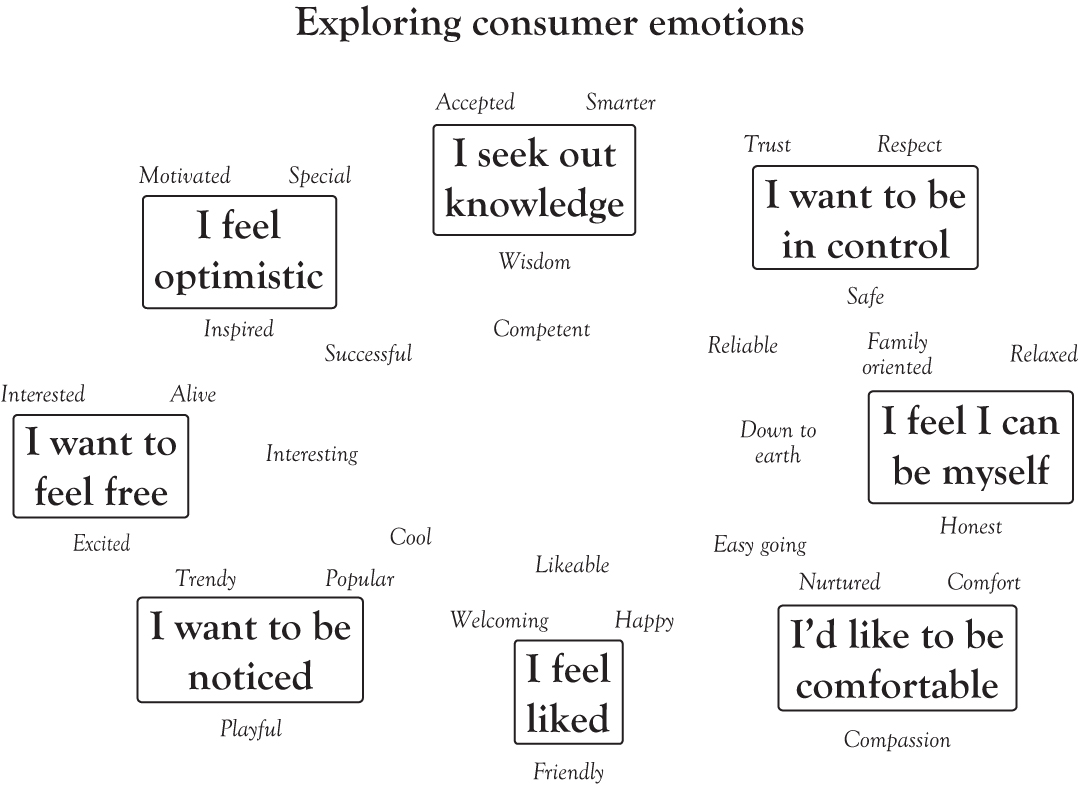

Graham Robertson, founder of the marketing firm Beloved Brands, described in a December 2012 blog how the research firm Hotspex has mapped out eight different emotional zones to help marketers identify optimal emotions for brands. These refer to specific feelings that could be used to align a brand to the specific need status of the target consumer and help define the emotional persona of the brand.

1.I feel liked

2.I want to be noticed

3.I want to be free

4.I feel optimistic

5.I seek out knowledge

6.I want to be in control

7.I feel I can be myself

8.I’d like to be comfortable

The specific emotions to describe the above feelings make up a spectrum denoting the range of consumer emotions, as follows:

Graham Robertson uses the positioning statement of Listerine Mouthwash as an example of how certain emotions from this spectrum were used—for example, how the consumer wants control, hence the main benefit consisting of confidence, which in turn was rooted in emotions such as trust and respect.

The Emotional Branding and Advertising of MasterCard

The MasterCard “Priceless” advertising campaign has become a modern classic of advertising. The favorable recall and attitudes generated by this global campaign reflect the emotional appeal of the relevant experiences and personal values depicted in each commercial. But this memorable advertising started with a major re-positioning effort, involving extensive research, identifying new insights, and adding a crucial emotional dimension to the MasterCard brand.

Brand imagery is the primary driver for all credit or payment cards. Research confirmed that the leading reasons for selecting a particular credit card were related mainly to experiential and emotional benefits:

1.Global acceptance of the card

2.How recognizable and trusted the card is

3.The annual fees

4.Interest rates

5.Reward programs

The perceptions of trust, reliability, and fit with one’s own personal aspirations are the key criteria for brand development in this payment card category. Both Visa and American Express had successfully created special brand identities, but until the late 1990s MasterCard had a perception of a generic, emotionally neutral payment card. From a positioning standpoint, Visa targeted itself against the elite “travel & entertainment” with the American Express card as its benchmark, creating an implicit comparison to the more upscale “achiever” image profile of American Express. In particular, Visa had maintained its advertising campaign of “Everywhere you want to be,” which appealed to those “bon vivant” consumers who are more materialistic and outer directed. The perceived image of each brand reflected the feelings and aspirations of its target customer base:

Visa: More lifestyle oriented, for those who yearn for the “high life”; more sociable, stylish, and on-the-go; reliable as it is accepted everywhere.

American Express: More professional, for the worldly executive, who desires a special membership, likes to charge as part of their business life.

MasterCard: More utilitarian, unpretentious, used for everyday purchases, practical, less special, almost unassuming.

The dilemma for MasterCard was its lack of a distinctive image, despite a solid base of card holders. Its focus was on the more functional benefits of using the payment card as an alternative to cash or checks, reinforced by its advertising (“It’s Smart Money” and “The Future of Money”). This brand message was not motivating and certainly did not hit any emotional “hot button” with consumers. As a result MasterCard’s market share continued to decline well into the 1990s.

With new marketing management, MasterCard embarked on a comprehensive research effort in 1996. The main objective was to better understand the current perceptions of MasterCard, and hopefully identify some new consumer insights that would help them re-position the brand. The main findings from this research were as follows:

Changing Consumer Values: The superficial, material-oriented attitudes and symbols for success from the 1980s to the early 1990s were being replaced by more traditional values: being in control, satisfaction with one’s own life, cherishing freedom and security, quality time with family, and being able to afford what’s really important to people.

Payment Card Usage: Whereas most consumers were aware of the problem of getting into debt, there was an emerging segment that was becoming becoming more careful about using these cards, and felt that only specific purchases could be justified—that is, “not frivolous purchases” or “what I want but can’t afford.”

Enriching One’s Life: Most important, this emerging group of consumers felt more comfortable and responsible using MasterCard for “things that really mattered to them.” It was clear from this consumer insight that there was a significant market opportunity for creating a proprietary positioning for MasterCard that leveraged this meaningful “everyday functionality” benefit among middle-American consumers.

The challenge then was how to leverage and convert this potential distinction into a benefit that was indeed more relevant and compelling—to give it some emotional power to get more consumers to feel more connected with the MasterCard brand. The answer was actually simple: identify a feeling that is emotionally powerful for different consumer segments and cultures, and position MasterCard as the ideal payment card to experience this “priceless” feeling, or “there are some things money can’t buy, for everything else there’s MasterCard.”

The magic of this answer was in how consumers interpret such a feeling, and importantly, how the experience could be enjoyed by not spending money on materialistic signs of success (i.e., as with Visa or American Express). The experience would cost money, but there is no way to measure the true cost of a feeling that can be so emotionally rewarding to consumers. This modified positioning also fits perfectly with the growing trend toward more meaningful purchases to improve one’s life. The beauty of this emotional benefit for MasterCard is that even though exactly “what matters most” will vary by consumer segment and country, the associated emotion or joy will always be “priceless.”

The Ultimate: Brand Equity

What Exactly Is “Brand Equity”?

It is not so difficult to define brand equity. It is more difficult to develop it and accurately measure it such that it becomes meaningful as a marketing tool.