4

Seeing The World Through The Eyes of Your Employees

You may have seen the hit TV show, Undercover Boss. The Brainchild of UK media executive, Stephen Lambert, the show was launched in the UK in 2009, and has now been rolled out to six other countries. The US series has been enormously popular, with around 18 million regular viewers.

Even if you haven't seen the show, you can probably figure out the storyline. The Chief Executive goes “undercover” for two weeks in his own company, to figure out how things really work. He sees problems that he had not been aware of and he is astounded by the dedication and skills of his workforce. At the end, he reveals who he really is, the employees are shocked, and the CEO resolves to be more open and responsive in the future.

The TV show inevitably focuses on the human interest stories – the wrongly dismissed worker, the single parent working a double shift, the choked-up CEO. But there are also some real management lessons for the Chief Executives who agree to take part. By stepping into the shoes of a front-line worker – and moving out of their comfort zone – for two weeks, they are potentially gaining experiences and insights they simply could not get any other way.

To see what the longer-term consequences of the undercover experience were, I talked to Stephen Martin, CEO of the construction, logistics, and property development company Clugston, and one of the stars of the very first series, broadcast in 2009.

Martin is a modest and reflective man, very keen to do things properly and to make a good impression. His manner is typical of the “quiet” leadership style that came into vogue a few years ago. As he recalls, his initial reaction when the production company asked him to appear in Undercover Boss was no – he did not fancy himself as a TV star. But eventually he came round: “In 2009 we were facing some big challenges, and I am the sort of guy who is always looking for new ideas. So I realized this was an opportunity to make some big changes in how Clugston was working.”

Three years on, the experience is still fresh in his mind. “When I did Undercover Boss, I wanted to experience the company from the viewpoint of the workforce. I just found it fascinating to see how everything I thought was working wasn't really working, or if it was, it wasn't working the way I thought it would be. And I also saw the damage I could do, accidentally, by putting in place a new procedure or idea.” On one large construction site, for example, it took 10 minutes to walk its length, so workers were spending most of the half-hour tea break travelling to and from the dining area. Martin endorsed a plan to “decentralize” the tea break, so workers could take a break wherever they happened to be working. But somehow this plan got interpreted as the tea break had been cancelled. How is morale? He asked one of his fellow labourers during his time undercover. “At an all-time low” was the response.

Immediately after his undercover stint, Martin made some changes that are still in place three years later. “Seeing things from the front line, I realized how poor we were at communicating. So now we have daily briefings for the direct labour force, weekly meetings with team reps, site notice boards, regular visits from senior managers, and a monthly newsletter, the Clugston Insider. I also introduced skip-level meetings where you discuss things with your boss' boss and brown-bag lunches where I sit down informally with the direct labour force to discuss what is going on. We also brought in a mentoring scheme so that our most experienced workers heading for retirement could pass on their knowledge to the next generation.”

Stephen Martin clearly got enormous value from his undercover experience, but when I recount his tale in my seminars, I sometimes get a slightly sceptical reaction. “If he had been doing his job properly in the first place, he wouldn't have needed to go undercover,” said one rather grumpy mining company executive.

So there is something a bit puzzling going on here. It is certainly true that a good boss spends time on the front line, getting to know people and exposing him or herself to the day-to-day issues they are facing. But in these situations, he or she is still the boss and they are employees, and the hierarchical nature of this relationship creates an invisible barrier that makes it difficult for employees to be themselves. As Stephen Martin recalls, “When I did site visits as the CEO, I felt people were just telling me what I wanted to hear. When I was working undercover, even with a camera crew following me round, people were incredibly open. It was just a completely different conversation to anything I had heard before.”

Martin is describing a well-known phenomenon, the human equivalent of Heisenberg's uncertainty principle (by trying to measure a particle, we disturb it). It is said that the Queen thinks the world smells of fresh paint, as she spends so much time going to grand openings of buildings and sites that have all been spruced up prior to her arrival. To a lesser degree, the same thing happens when you, as an executive, show up on the shopfloor, or even in the pub. You want to know what is going on, but your mere presence changes the dynamics of the conversation. Sometimes the workers may be overly polite and positive; at other times they may pluck up the courage to be critical, but in both cases the message is a “noisy” one that may or may not be representative of what is really happening.

This chapter is all about what you can do as a manager to see the world through your employees' eyes. Most bosses don't have the possibility of going undercover, but of course there are plenty of alternative ways of approximating the undercover experience – getting most of the benefits, but without the same level of investment. I will discuss what some of these are and I will also look at a range of other techniques and concepts to help you reframe the way you look at your organization.

Putting Yourself in Their Shoes

Before getting into all this, let's briefly take a step back. The notion that you need to see the world through the eyes of others isn't unique to the field of management. The best teachers, for example, have the ability to empathize with their students' learning difficulties. And most professions – from doctors and psychotherapists to solicitors and consultants – have clients whose needs have to be divined and addressed.

In all these professions, the value of the client perspective is recognized but is still very hard to fathom. Consider the case of US surgeon and television personality, Dr Mehmet Oz, who in 2010 had a cancer scare – a couple of precancerous polyps on his colon. While the polyps were caught in time and duly removed, the experience of living through the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up was a real eye-opener for Dr Oz. It was the first time he had taken the role of patient in the doctor–patient relationship, and the way he behaved took him by surprise. For example, he was meant to go for a check-up 3 months after the initial treatment and he stalled – he scheduled the check-up, then he cancelled, and procrastinated when asked to reschedule. As he recalled, “I was engaging in behaviors that had left me dumbfounded when my patients exhibited them.1”

He eventually rescheduled his check-up and was given the all-clear. But why did he stall? Trying to make sense of his behavior after the event, he recounts: “… I finally had the epiphany. We are uncomfortable being uncomfortable. We avoid being tested because it creates enormous uncertainty. I have learned to embrace uncertainty. I am pleased that what I learned will help me.” The learning here isn't just advice to the people watching his TV show – I think he will also become a better doctor, especially when it comes to helping people take responsibility for going to their scheduled check-ups.

I had an epiphany of my own a couple of years back. In fact it was one of the simple-yet-profound insights that inspired me to write this book2. My wife and I were looking to upgrade to a bigger home, so we arranged for the real estate agent to come round and do a valuation of the place where we were living. The day before, my wife suggested we spend a few hours tidying the place up, so that it looked its best. Frankly, I couldn't see the point: surely the real estate agent would be able to figure out what it was worth, regardless of how neat and tidy everything looked? But of course, as a dutiful husband, I went along with the plan anyway, and I did my best to tidy, hoover, plump cushions, and dust. But my heart wasn't in it and my hoovering and dusting skills aren't that strong either. I would clean a room, then my wife would come in after me and clean it again. Soon I found myself checking my Blackberry when my wife was in a different room and deliberately working slowly. Then my mind began to wander and it hit me: this is what it feels like to be an employee. I didn't really understand why I was doing the work and I didn't have the skills to do it well. So I was behaving like a recalcitrant worker – doing the bare minimum to get by, but stalling and idling when given half a chance. I wasn't sabotaging things like the Northern Plant workers in the previous chapter, but I wasn't engaged or motivated either.

The point of the story is the following: for the next couple of weeks, while this learning was still very fresh, I behaved very differently at work. I took much more care with my secretary and my PhD students to clarify what they were doing and why, to structure their work more carefully, and to make sure they had the resources they needed. The adjustments I needed to make were small, but thanks to my home-cleaning experience I took the time to make them.

So why is this sort of mental transposition so powerful in the workplace? I think there are three linked reasons:

- First, and most importantly, it allows you to understand properly what motivates and concerns the other person. Dr Oz couldn't figure out why patients would cancel their check-ups until he found himself doing the same thing. I had never understood why there is so much time-wasting in the workplace, until I found myself doing it myself while tidying my home.

- Second, by playing up the view of the other person, you automatically downplay your own perspective. In the words of John Lilly, CEO of Mozilla, “When I think in terms of helping people learn to be even better, it automatically puts me into an empathetic mode.3” This approach helps you take your own ego and interests out of the equation – an important trait in a good manager.

- Third, putting yourself in the position of the other person makes you more human in their eyes. By changing how you relate to your employees, you are likely to see a reciprocal change in behavior on their part as well. Stephen Martin recalls how the Undercover Boss production company came back to his company two years after the original show and there was still a positive buzz across the company. Workers could see that management were trying to make improvements, even if they didn't always work, and to take their views into account.

Lessons from Marketing

The notion that we should look at the world through someone else's eyes is an old one. Everyday expressions such as exhorting someone “to walk a mile in another's shoes” or to employ someone as a “poacher turned gatekeeper” tap into the same underlying sentiment. However, I think there is some real mileage to be gained by taking the idea seriously, if we can find a way of being systematic about it. Fortunately, there is an enormous body of research and techniques we can make use of in this exercise, namely the field of marketing.

The definition of marketing that has stuck in mind, from when I first studied the subject 20 years ago, is seeing the world through the eyes of the customer. If you think about it, the reason we need marketing and marketers is simply that many people fall into the trap of being product-centric: they focus narrowly on the product itself and the clever features it offers, and they neglect the actual needs or concerns of their prospective customers. Companies as different as GM, DEC, Philips, Ericsson, and Kodak have all, to varying degrees, fallen into this trap. Marketers see their job as helping their companies avoid the product-centric trap. Their role is to provide a set of tools, techniques, and frameworks to help companies understand the wants and needs of their prospective customers, and to figure out how to address those needs more effectively.

My simple proposition here is that we can take 60 years' worth of marketing expertise, all focused on developing better ways of seeing the world through the eyes of the customer, and we can apply it to the field of management, which is about seeing the world through the eyes of the employee. This is not a novel idea as such, but applying it systematically to the various elements of management has not been done before.

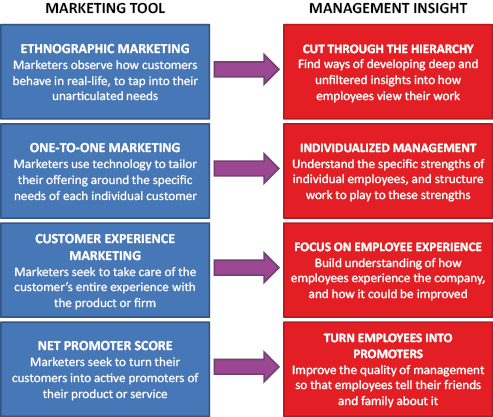

Figure 4.1 illustrates the overall logic. I have picked out four key themes in the world of marketing and for each one I have identified the analogous theme in the world of management. For each one, we can identify some specific tools and frameworks that can be used directly by managers, to help them understand and relate to their employees more effectively.

Figure 4.1 Applying Marketing Concepts to the Field of Management

A quick note of clarification before proceeding. I make no claim here that I have uncovered some secret new way of managing employees; all the concepts I describe here can be found somewhere in the Human Resource Management literature. However, sometimes a new angle on an old problem is useful. A change in perspective, as they say, is worth 50 IQ points. Hopefully, by looking at these challenges through a different frame, you will see opportunities for managing your employees a little differently.

Cut Through the Hierarchy to Build Employee Insight

An important technique in the field of marketing is ethnography – the study of customer behavior in its naturally occurring context. Academic research in marketing has used ethnography since the 1970s, but over the last 15 years or so the technique has been increasingly adopted by professional marketers as well.

Marketers have embraced ethnography because there is only so much insight you can get from a focus group, survey, or taste test. We know that customers often don't behave the way they say they will (New Coke was a hit on paper and a disaster in practice), and we know that customers struggle to articulate their unmet needs (Henry Ford's customers reputedly wanted a faster horse). So increasingly, marketers have figured out that you get real insight only by “living with” customers in their natural habitat – following them round the supermarket, watching them cook dinner, and observing them as they struggle to get their kids to try new foods. Good ethnography yields insights about customers that they themselves are unaware of. Procter & Gamble's Swiffer cleaner, for example, was invented when Harry West, a leader on the soap team, observed a woman wipe the floor with a paper towel4. He didn't ask her how to improve the traditional mop, but by watching her in her natural setting he was able to make the creative leap that resulted in the Swiffer – a product that became a $500m per year revenue earner for the company.

How can we apply the marketing concept of ethnography to the practice of management? Well, hopefully the answer is pretty obvious. We saw in Chapter 3 that employees have a self-identity, a view of themselves that they seek to reinforce through their behavior. But they often struggle to articulate what this identity is. Their knowledge about themselves is tacit – they know more than they can tell. So just as ethnographers seek to divine insights from customers about their latent needs by observing them, good managers seek to generate an understanding of their employees, by picking up cues about what engages them and what turns them off.

Ethnography is also a way of breaking down barriers. People can be very defensive when asked straight market research questions, so ethnographers work hard to put their subjects at ease and to gradually build their trust. Equally, as we saw at the beginning of the chapter, employees are always on their guard when the boss is in the room, for fear of saying something wrong or letting information slip. So the boss has to find creative ways of overcoming their defensive behavior.

An ethnographic approach to management actually looks a lot like what Stephen Martin did for two weeks as an undercover boss. While he didn't use this term, the principles are exactly the same: he observed his employees in their natural environment, without “disturbance” from top management, and he got them to articulate their views about how things were going.

I appreciate that it isn't too practical for you to put yourself on an undercover assignment, so we have to think creatively about alternative approaches that go some way towards providing the deep insights into our employees that we need. Here is a list of some of the approaches I have seen:

- Institutionalized “skip-level” meetings. Skip level simply means meeting with people two levels above (or below) you in the hierarchy. Some companies have a strong informal norm that you don't break the chain of command. This norm helps to build accountability, but at the same time it restricts the flow of information. Stephen Martin realized this was happening at Clugston, so he introduced skip-level meetings as a way of getting senior executives more involved in the day-to-day realities of the business. By scheduling them regularly – every two months – they simply became a standard part of the manager's job. Martin also introduced informal “brown bag” lunches with employees to serve a similar function.

- Web-enabled chat and discussion forums. In large companies, it is simply impossible for all employees to meet their top executives. However, technology provides a mechanism to give people at least a virtual connection to the top. For example, the Indian IT Services company, HCL Technologies, has a tool on its Intranet called You & I, where the CEO gives direct answers to questions posed by employees. A voting system is used to prioritize the questions and then, once a week, Nayar sits down for a couple of hours and writes answers to the questions at the top of the list. Many companies have also been experimenting with microblogging tools such as Yammer (recently bought by Microsoft). Microblogging allows employees to sign up to conversation threads about topics of interest to them, and it encourages informal, nonhierarchical discussions. At CapGemini, for example, Yammer has become an important tool. As explained by former Chief Technology Officer, Andy Mulholland, it provides “vital insight into what's going on across our business” while also providing “social glue” for the 20 000 employees who have signed up to it (I will discuss this case in more detail in Chapter 7).

- Executives doing front-line work. This is the simplest and best-known way of cutting through the hierarchy. For example, executives at Tesco, the biggest UK supermarket chain, spend one week every year working in the stores – on the checkout desk, behind the fish counter, stacking the shelves. While this isn't undercover work – everyone knows the grey-haired guy behind the counter is the CEO – it still serves to remind executives of the day-to-day issues their employees have to deal with, and it makes them look a lot more human as well. There are even some industries where executives see front-line work as part of their job. The Managing Director of a John Lewis store, for example, will spend an hour or two every day on the floor, serving customers alongside his staff. In my world, many business school Deans still find the time to teach the occasional MBA course.

- Smokers' corner. These days, smokers find themselves driven out into the parking lot, or on to the streets outside their office building, to indulge their craving for nicotine. The one silver lining for these marginalized individuals is that they often find themselves chatting to people they wouldn't otherwise bump into, while having their cigarette. This is the sort of forum where gossip is shared, and perhaps because the relationship is smoker to smoker, rather than employee to boss, the usual hierarchical barriers seem to be suspended. I have often heard senior executives comment that they pick up on the “pulse” of the company more in their 15-minute cigarette breaks than they do in any number of formal meetings.

Of course, taking up smoking as a way of finding out what is happening in the company would be a rather drastic step to take, but there are other pursuits that also cut across the usual barriers. I know senior executives who are members of the squash and running clubs in their organizations, and these also provide a nonhierarchical window on what is going on. - Reverse mentoring. A traditional mentoring relationship is a way for a seasoned professional to share wisdom with a more junior person who is still learning the ropes. However, the speed of change in the world of technology has given rise to the concept of reverse mentoring, in which a young, tech-savvy employee helps an older manager to get up to speed in the latest developments in technology. When it works well, this form of reverse mentoring can be a great opportunity for both parties. For example, one of the people I interviewed for this book is Ross Smith, a late-forties executive at Microsoft. He is being mentored by a 28 year old, to keep him up to date on new social media applications and to get him into the mindset of so-called “Gen Y” employees. Unlike traditional mentoring, this ends up as a two-way relationship, and they end up discussing a wide range of issues on a much more informal basis than would be possible usually.

This is not meant to be a comprehensive list. There are many traditional techniques that I have not talked about – from town hall meetings to “Management by Walking Around” – that all help you cut through the hierarchy to various degrees. For you as a manager, the trick is to choose something that fits your own style of working, so that your employees recognize it as an authentic attempt to understand their point of view.

Individualizing the Employee Proposition

In the field of marketing, there has been a significant evolution in thinking about how to address customer needs. In the early days of marketing, adverts on TV, radio, and billboards were a form of mass marketing, with all potential customers receiving the same message. This one-size-fits-all approach gradually gave way to market segmentation, with subgroups of potential customers being identified and targeted with different offerings. The trend nowadays is towards one-to-one marketing or mass customization, in which the offering is tailored to the specific needs of the prospective customer. Examples include Amazon sending you personalized recommendations on the basis of your previous purchases, Yahoo! allowing you to specify the various elements of your home page, and Dell letting you configure the various components of your computer before it is assembled. These offerings have been enabled by technological innovation. While one-to-one marketing used to be feasible only for very high-end customers, advances in flexible manufacturing and online analytical techniques have brought the potential of customization to the masses.

How can we apply the principle of one-to-one marketing to the practice of management? Again, the basic intuition here should be pretty clear. In the industrial era, manufacturing companies employed people primarily to do manual labour and one worker was much like the next. As Henry Ford famously said: “Why is it that whenever I ask for a pair of hands, a brain comes attached?” But in today's knowledge economy, most employees are hired for their brains, not their hands. This makes for a far more heterogeneous workforce, where all workers have their own unique skills and capabilities. What workers want, in other words, is jobs that are customized to their needs.

Unfortunately, most companies are still stuck in an industrial era mindset. Most low-end jobs are designed so that individual workers can be swapped in and out at minimal cost (e.g., hamburger flipping or telephone sales). Even in higher-end work, it is still standard practice to define generic jobs that any qualified employees can slot themselves into. According to this model, employees are expected to adjust themselves to the roles they are assigned, rather than the other way around. In the language of marketing, jobs are still for the most part “off-the-rack” rather than “made-to-measure” creations.

The management challenge for companies is to see how far the principles of one-to-one marketing can be applied to the employee relationship. Conceptually, this means individualizing the employee proposition, that is, creating a better match between the demands of the job and the capabilities of the employee. As usual, this is an idea that has been around for a while. Marcus Buckingham's work on strengths, described in Chapter 3, builds on this premise, as does Chris Bartlett and Sumantra Ghoshal's book The Individualized Corporation. Some of Peter Drucker's work also anticipated this trend: “The goal [of management],” he wrote, “is to make productive the specific strengths and knowledge of each individual.5”

Let's be clear: designing work around employees, rather than vice versa, is a costly business. Just as in marketing, we need to balance the company's need for efficiency and standardization with the employee's need for a “tailored” job that matches unique skills. Particularly in industries where talent is scarce, there is a lot of scope for putting more emphasis on tailoring the job to the individual, because that is what will encourage employees to stick around. As in the field of marketing, new technologies are making it possible to shift the trade-off, to get the best of both worlds. Here are a few examples of what I am talking about:

- HCL Technologies, the Indian IT services company, has developed a tool called “Employee Passion Indicative Count” (EPIC), which I described briefly in Chapter 3. EPIC is a survey employees fill in to indicate how excited they are about various aspects of their work – who they are as individuals, what work they like to do and where, and who they like to work with. At an aggregate level, this survey provides the company with important insights into what motivates their workers: for example, in 2010 the top passion indicator for male employees was “customer support” whereas for female employees it was “collaboration.” EPIC also works as a management tool. “Each line manager reviews his employees' EPIC scores,” explains Anand Pillai, former head of talent management at HCL, “and this opens up a conversation about what sort of work he should be doing. We discovered some employees wanted to do customer-facing work, while others showed a preference for back-office activities like testing software and doing documentation. In many cases, we are able to move people to jobs they are more excited about. In cases where we cannot make the match immediately, we help them build the competencies they need to move.6”

- Ross Smith is Director of the 85-person Lync Test team at Microsoft and an ardent believer in the employee-centric approach to management. When Microsoft Lync 2010 was released, preparation for the next version began. Smith realized that a reorganization of the team would be needed, but he knew how disruptive and demotivating such changes can be. So he and his team decided to experiment with a bottom-up process that the entire team would be involved in, what they dubbed a “we-org”. Rather than asking his four direct reporters to pick their teams, they asked individual contributors to select which teams they would like to be in. As explained by Dan Bean, one of Smith's management team, these individuals “became free agents, looking for an optimal position, much like a sports star.7” The four managers were not in a position to offer more money to these free agents, but they could offer them opportunities for growth, new technologies to work on, and new colleagues to work with. The individual contributors quickly warmed to this new process. “The initial feeling was, oh, it's a reorg again, nobody was excited that it was happening. But after the meeting [with Ross Smith], it became clear they were really serious about accommodating everyone's choices. The next couple of days we saw marked changes. Now it was about what have you decided? rather than what did you get?” The we-org took longer than anticipated, but the bottom line was that 95% of the team liked or somewhat liked the new method, and only two individuals out of 85 felt that they did not end up with a satisfactory placement in the new structure.

- AdNovum is a Zurich-based software company founded by Stefan Arn. Around 2002, the company had grown to around 30 people and Arn realized he needed to build some sort of system for matching his employees to projects. In his market for security software, flexibility was also important. “So we developed a Facebook-like system on the Web where you as an employee could portray yourself, especially your skill set, for others to review,” he recalled, “and we encouraged people to keep their CVs and their skill sets as accurate as possible.” Very quickly, the new system became something of a competition: people could apply for a project by looking at the pipeline of new projects and deciding which ones suited their skills and preferences, while at the same time project heads were calling up the people they wanted. Using the data on how many times developers were asked for by projects, Arn developed a performance-based ranking, which he then posted on the Intranet for all to see. He also linked the individual's position in the ranking system with their bonus8.

While these three examples differ on many points, the common principle is clear: give employees more choice over what they do. At HCL, EPIC is about helping employees to articulate what they are passionate about and building these preferences into their development plan. At Microsoft, the we-org was about letting employees choose their role in the new structure. At AdNovum, the system Stefan Arn created allowed people to apply for specific projects, according to their skills and motivations.

Are we seeing a trend towards the employee equivalent of one-to-one marketing? Well, there are plenty of companies experimenting with this type of approach, but the management effort required in structuring work around the needs of individual employees is substantial. Ross Smith's we-org was a success, but perhaps only because he had already established a high level of trust within the team for his unconventional approach to management. While AdNovum's market-based model for matching people and projects worked well while the company was small, as it has grown it has gradually adopted a hybrid project–management system, using much more of the traditional top-down approach. There is a tension, in other words, between the broader demands of the organization and the specific needs of the employee, and an important part of the manager's job is to get the right balance between these two opposing forces.

Managing the Employee Experience

One of the big trends in the field of marketing over the last 20 years has been an increasing focus on the customer experience. It is argued that increasingly customers are buying an experience, not a product or service. That is why we are prepared to pay $4 for a coffee at Starbucks – we are buying a pleasant coffee-drinking experience with comfy chairs and jazz music, rather than a cup of hot caffeinated liquid.

To turn this broad idea into something practical, marketers have sought to understand why some companies – Apple, Porsche, Virgin Atlantic – are able to generate consistently positive views about how people experience their product or service, while their competitors are not. Certainly there are intangible aspects of the brand at play here, but of far greater importance are the “touch points” where the customer or potential customer interacts directly with the product or the company. The legendary CEO of Scandinavian Airlines (SAS), Jan Carlzon, called these the moments of truth. Your experience as an airline passenger, he argued, is defined more by how you are treated at check-in, at the gate, or on board the aircraft, than it is by the actual food you are served or the route you flew.

As always, there are several different marketing tools out there to help companies manage their customer experience. One is Customer Experience Management, defined as “the process of strategically managing a customer's entire experience with a product or company9”; another is the Service Profit Chain, which is about defining and managing the sequence of activities that drive customer satisfaction and loyalty in service industries (e.g., airlines, banks, retailers). The common theme, for our purposes here, is simply that customers develop a perception of the product or company largely through human interaction. The technical qualities of a product matter, but the way the product is experienced is more important.

How can we apply these marketing insights to the practice of management? Employees, like customers, enter a relationship with a company that they can exit at any time. However, it is in the interests of the company to retain both its customers and employees. There is solid evidence that loyal customers drive long-term profitability. There is equally solid evidence that low turnover and talent retention are key dimensions of organizational health.

So what are the factors that explain employee turnover? Salary is obviously part of the story, but actually a surprisingly small part. There are also long-term factors, in terms of whether employees find the work engaging and whether the company gives the individual opportunities to develop. Many employees quit before these issues even begin to surface. Some industries have employee turnover rates above 50% per year. In these high-turnover industries – hotels, restaurants, call centers – a particular problem is people quitting within a couple of months of starting.

It is this early-stage turnover that the research on customer experience can really help. I believe companies can do a much better job of managing the employee experience. This includes the various touch points the employee has with people in the company, especially in the first few months, as well as the physical working environment and the day-to-day routine of work. If this initial experience is poor, the employee gets a bad initial impression and often will not wait to find out if things could improve.

Increasingly, companies are looking for thoughtful ways of managing the employee experience. Consider two examples from sectors where employee turnover rates are typically very high:

- [24]7 Inc., headquartered in Campbell, California, provides innovative customer service solutions to its clients. Most of its 10 000 employees work in service centers in India, Philippines, and Guatemala, and employee turnover rates in these cities is often as high as 100% per year. The company's co-founder and Chief People Officer, Shanmugam Nagarajan (Nags), explained how he keeps turnover rates down to about half the industry average. “I spend about a quarter of my time on the road, meeting with around 500 front-line employees every quarter, listening to their concerns and following up with fixes. Transparency and accessibility are key values in the company. We have also put in place what we call ‘90 day surveys.’ Our analysis showed that if new employees make it through the first 90 days, they are likely to stick around. So we focus a lot on those first touch points when a new employee starts, and we survey them. Are you satisfied with the office? The food? The transportation to work? Do you have the support you need? Often we can make small changes as a result of these surveys, and that creates a positive experience that encourages employees to stay. For people who have been with us a while we also have a training program, ‘Wings Within,’ for helping employees to make internal transfers into different functional areas.10”

- HCL Technologies has what it calls a “Smart Service Desk” (SSD) for its employees. This concept was borrowed directly from the world of marketing. Many companies use service tickets as a way of monitoring and following up on customer complaints. Vineet Nayar, former CEO of HCL Technologies (now Vice Chair), had the bright idea of applying this approach inside the company. As he explains, “Value is created by employees in their relationship with customers. So management's job is to serve the employees. The Smart Service Desk is one of several tools we have created to help management serve the employees better.” As an employee at HCL, if you are unhappy about some aspect of your work, or need a problem resolving, you open a Service Ticket with the relevant manager, perhaps the head of human resources or the facilities manager in your office. It is up to that person to resolve the problem and the ticket is only closed when the employee is satisfied. This IT-enabled system keeps track of the number of tickets being opened and how quickly they are closed. Unresolved tickets are then escalated to higher levels in the company. The SSD concept puts the onus on managers to become more service-oriented, so that employees feel they are getting a good experience.

These two examples are based on low-end jobs in the high-turnover IT sector, largely because the challenges are so acute here. Clearly the concept of improving the employee experience applies much more broadly as well. There is room for considerable creativity here, in dreaming up novel ways of enriching your employees' experiences in the workplace.

Turning Employees Into Advocates

Finally, an important theme in marketing over the last decade has been the idea that the best advocates of a company or its brand are its own customers. It has always been true that word-of-mouth promotion is the most powerful endorsement you can receive for your product. In the online world, the power of customers-as-advocates has increased dramatically: a favorable review, tweet, or blog from someone who raves about your product can quickly reach thousands of potential customers. The reverse is also true: a disaffected customer can make your life miserable very quickly. In 2009, musician Dave Carroll posted his song “United [Airlines] Breaks Guitars” on YouTube and within four days the company's share price had dropped 10%.

Fred Reichheld, author of The Loyalty Effect and The Ultimate Question, has pushed this concept of customers as advocates furthest through his development of the “Net Promoter Score” (NPS), which is based on answers to the question “How likely is it that you would recommend our company to a friend or colleague?” By taking the “promoters” (who give a score of 9 or 10 out of 10) and subtracting the “detractors” (who give a score of 6 or lower out of 10), you end up with a single net score (a percentage of the total number of respondents), which indicates how much customers are talking positively about your company. Many large companies use the NPS as a key performance indicator, and it has been shown to be highly correlated with long-term performance11.

How can we use this concept to help improve the practice of management? Clearly, it makes sense that we want our employees to be positive advocates of our company. Engaged employees are likely to talk up the company and its products to their friends, which in turn is good for sales and for attracting new employees.

We can go further. Reichheld's research makes the point that you don't just want satisfied customers, you want customers who are sufficiently “wowed” that they say it is “extremely likely” they will recommend you to a friend or colleague. These are the ones that make a real difference, the ones who make “viral” marketing happen. I think the same is true of your employees. Of course you want happy and engaged people working in your company, but it's the highly engaged ones that make a real difference, because their enthusiasm is infectious.

In 2010, I was working with a team from the Swiss pharmaceutical company, Roche, who had the bright idea of applying the Net Promoter Score internally. They developed their own metric, which they called the Net Management Promoter Score (NMPS). The question was worded as follows:

How likely is it that you would recommend your line manager to a colleague, as someone they should work for in the future (1 = not at all, 10 = extremely likely)?

The team's thinking was that this question would be a useful way of getting a grip on the overall quality of management in the company. They really liked how sharp and to-the-point it was. “I have often filled in pages and pages of questions in 360-degree feedback surveys about people in my organization, and after a while you lose focus,” recalled Jesper Ek, one member of the team. “If we could narrow down to a single, meaningful measure, everyone would benefit.12”

The team trialled the NMPS with a subgroup of managers and they showed that it was strongly correlated to Roche's broader measures of employee engagement. The results were presented to various senior executives, two of whom quickly incorporated the measure into their own quarterly employee survey. “I would like to see it used to compare the performances of different regions or business units, over time,” said Jesper Ek. “An improving aggregated score year-on-year would be a great advert for prospective employees. NMPS could even be used as a means of comparing the performance of our own business with that of a competitor. There is huge scope to expand the concept.”

Following the success of this Roche experiment, I have also used the NMPS in some of my research. I think it potentially serves two purposes. First, it is a useful overall indicator of the quality of management in a unit or organization. For example, in the survey I described in Chapter 3, the NMPS ranged from −28% in one company through to +61% in another. In the lowest one, there were 28% more people who were detractors than promoters of their managers and in the highest there were 61% more promoters than detractors. This compared with an overall measure (for the sample as a whole) of −15%. By tracking this number over time, you get an interesting indicator of how well managed a company is.

The NMPS could also potentially be used as feedback for individual managers, as one indicator of how good a job they are doing. It's worth underlining that Fred Reichheld's research showed that a score of 6 out of 10 (or below) is negative and it is only a score of 9 or 10 out of 10 that really counts as a positive endorsement. This means that many managers end up with more “detractors” than “promoters” – this is tough feedback, but ultimately very useful if you want to create an organization where your employees can do their best work.

I plotted the NMPS against an established measure of employee engagement and the results (see Figure 4.2) suggested a very strong correlation of 0.75. Remember, employee engagement is an indicator of how much discretionary effort a person is likely to put into their job and it is influenced by a range of factors, including the nature of the work itself, the physical working environment, the opportunities for development, and the quality of colleagues. This chart simply says that all these other factors are secondary – it is the quality of your immediate boss that has the biggest single impact on your overall engagement at work.

Figure 4.2 Employee Engagement and the Net Management Promoter Score

Thinking Like a Marketer

In this chapter, I have shown how you can apply your employee's eye-view to the work of management. As always, the challenge is moving from concept to practice, which is why the techniques from the world of marketing are so useful. Marketers have developed an impressive toolkit to help them tap into and address their customers' needs, and quite a few of their tools are immediately applicable to the world of management.

Indeed, I am sure there are other marketing techniques that could have potentially been discussed here. I encourage you to think creatively about all the different approaches you can use to get closer to your customers and to see if those principles could also help you become a better manager.

Notes

1 Time Magazine, June 27, 2011, From Dr Oz to Mr Oz, page 34.

2 I recounted this same story in an earlier book, Reinventing Management. Apologies to those (few) readers who have actually read both books in their entirety.

3 Taken from Bob Sutton's blog, May 6, 2010, Boos an Empathy: CEO John Lilly on why the best leaders think and act like teachers, Bobsutton.typepad.com.

4 The story is taken from Imagine: How Creativity Works by Jonah Lehrer, Canongate Books, 2012.

5 Page 1 of The Essential Drucker by Peter Drucker, Taylor & Francis Group, 2007.

6 Author interviews with Anand Pillai.

7 Dan Bean wrote this story on the Management Innovation Exchange website: http://www.managementexchange.com/story/we-org.

8 Julian Birkinshaw blog, Getting the Right People on the Right Projects, http://bsr.london.edu/blog/post-34/index.html.

9 Bernd Schmitt, Customer Experience Management, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2003.

10 Author interviews with Shanmugam Nagarajan (Nags). See corporate website: http://247-inc.com.

11 Frederick F. Reichheld, The Loyalty Effect, Harvard Business Press, 1996.

12 Julian Birkinshaw, “A True Measure of Leadership,” Labnotes Issue 21, www.managementlab.org.