One of the best things about Ubuntu is that it’s ready for use as soon as it’s installed. As soon as you reboot, you can get almost anything done immediately, and new applications are just a couple of clicks away. Some of the power of Ubuntu is in its differences from other operating systems.

Ubuntu is best approached as its own experience, without comparison to other operating systems—in fact, all operating systems are best approached this way. Therefore, the rest of the chapters in this book talk about Ubuntu directly. But it’s hard to leave behind the habits and experience we’ve formed from working with computers. You’re probably fairly handy with a computer running Windows or OS X. This chapter will help you take what you already know and apply that knowledge to Ubuntu, so that you feel comfortable more quickly. And it will help you work more closely with your other computers as well. It’s a lot like a travel guide, complete with a phrasebook!

All modern operating systems using the desktop model of interaction have the same fundamentals. You can think of switching between them a bit like visiting a different country. There are different languages and customs, but with a bit of preparation, you can fit right in.

Try to think of learning a new operating system like the same kind of adventure, and you’ll find the experience a lot more fun—and enjoyable.

Setting Up Your Computer

A screenshot of the Ubuntu connect your online accounts window has options for Ubuntu single sign-on, Google, Nextcloud, and Microsoft.

Connecting Ubuntu to your online accounts gives you access to your data in the cloud

The second screen prompts you to set up the Ubuntu Livepatch service from Canonical. This allows your computer to automatically protect itself from security vulnerabilities in the Linux kernel that powers everything else. This keeps you protected until you can install an updated kernel via the standard software update process and restart your computer. This isn’t urgent for home desktop use, but for business desktop and server use, it’s a really nice feature. Livepatch is free for every individual for up to three computers. If you didn’t connect an Ubuntu One account on the previous screen, Ubuntu will help you log in if you click “Set Up Livepatch…” Or, you can click Next to continue without setting up Livepatch. You can always set it up later in the Software & Updates application .

The third screen allows you to help Ubuntu understand how it’s being used by periodically sending information about your system to Canonical. This helps Ubuntu developers better understand how it’s being installed and used. Ubuntu occasionally publishes a report about how many users are running Ubuntu, where, which versions, and so on. The information isn’t personally identifiable, and you can see what information is transmitted by clicking “Show the First Report.” You can also choose the option “No, don’t send system info,” and no information will be sent. Click Next when you’ve chosen to send or not to send information about your system.

A screenshot of the Welcome to Ubuntu Privacy window has the slider for Location Services turned off.

You can allow Ubuntu to detect your location so that programs can provide tailored information

A screenshot of the Welcome to Ubuntu Ready to go window has a variety of popular third-party software like Code, Zoom-client, Spotify, V L C, and more.

Hundreds of applications have been packaged especially for you to use with Ubuntu

Ubuntu Desktop

A screenshot of the Firefox web browser on the Ubuntu desktop with a panel on the left.

This is the default Ubuntu desktop with a web browser running

Ubuntu Dock

On the left edge of the screen is the Ubuntu Dock . This is where you can pin and launch your favorite applications, and see which applications are running. Clicking the Activities button at the top left of the screen or pressing the Super key (the Windows Logo or Command key) opens the Activities overview, and the bottom icon in the bottom left of the screen shows a list of the desktop applications installed on your computer (except the ones that are pinned to your favorites in the Dock). You can click an app icon to launch the corresponding application. Running applications will have a pip on the left, and will display two or three pips if two or three windows are open, or four pips for four or more windows. Clicking a running application’s launcher icon will focus that application and its window to the foreground. If an application has more than one window open, clicking the icon again will display the windows as thumbnails. You can then click a thumbnail to bring that window to the foreground, or click the X button in the thumbnail’s top right corner to close that window. Middle-clicking, or holding Shift or Ctrl and clicking a running application, will launch a new window of that application.

Right-clicking on an application icon will display a quick menu that lists application-specific commands. Different commands may be available depending on whether the application is currently running. The quick menu will also list all open windows, which can be selected with the mouse. The “Quit windows” option will close all open windows of that application.

Adding an application to your favorites keeps the icon displayed on the top half of the Dock when it is not running. This gives you instant access to your favorite and most-commonly used applications at the top of the Dock with a single click. Simply drag the icon to the top of the Dock to add it to your favorites. You can also right-click on an icon while the app is running or in the applications list and choose “Add to Favorites.” To remove an app from your favorites, you’ll have to right-click its icon and choose “Remove from Favorites.”

You can rearrange your list of favorite apps by dragging them around the top half of the Dock. You can hold down the Super key and press a number key to automatically run or (switch to, if it’s already running) the corresponding launcher icon, so arranging them can help you launch applications even more quickly. However, GNOME Shell doesn’t display these numbers when you hold down Shift, so you will have to count the icons yourself.

You can make the Dock disappear until you need it by turning on the auto-hide feature. To do this, run Settings from the Activities overview or the system menu at the top right of the screen. Click the Appearance option on the left of the Settings application, and turn on “Auto-hide the Dock.” This setting takes effect immediately, so you can test it out before closing Settings. By default, the Dock will be visible unless you have a window that would overlap it. When hidden, the Dock will appear when you push the mouse pointer “past” the left side of the screen. This gives you fast access to the Dock without it getting in the way of running applications.

The bottom of the Dock shows mounted storage devices (such as hard drives or USB storage) that are attached and ready to use (called “mounted” in Ubuntu), and you can right-click on a storage icon and choose “Unmount” to get it ready to remove. The last icon in the Dock before the application list is your Trash folder. You can click on it to view (and restore) deleted files that have not yet been removed from your computer, but you cannot drag files onto it.

Activities Overview

A screenshot of the activities overview on Ubuntu has open windows such as the Calculator, Libre Office Writer, and the Firefox web browser running.

The Activities overview shows your open windows and any active workspaces

In the Activities overview , you can simply click on a window to focus it and bring it to the top of your other applications. You can also drag them from one monitor to another, or to different workspaces. A workspace is a way to group windows together in a collection of related activities, and you can use them to work on certain tasks without the clutter of having unrelated windows in the Activities overview or task switcher. In addition to dragging a running application to a new workspace, from the Applications list, you can drag an icon to any existing workspace at the top of the screen, and it will open on that workspace. Workspaces are covered in detail in Chapter 6 under Using Multiple Workspaces, but for now you should know that you can move between workspaces by clicking on them or scrolling through them in the Activities overview screen with your mouse wheel, additional workspaces do not take up additional memory or computing resources, and there will always be one empty workspace on the right that you can begin using by dragging a window to it.

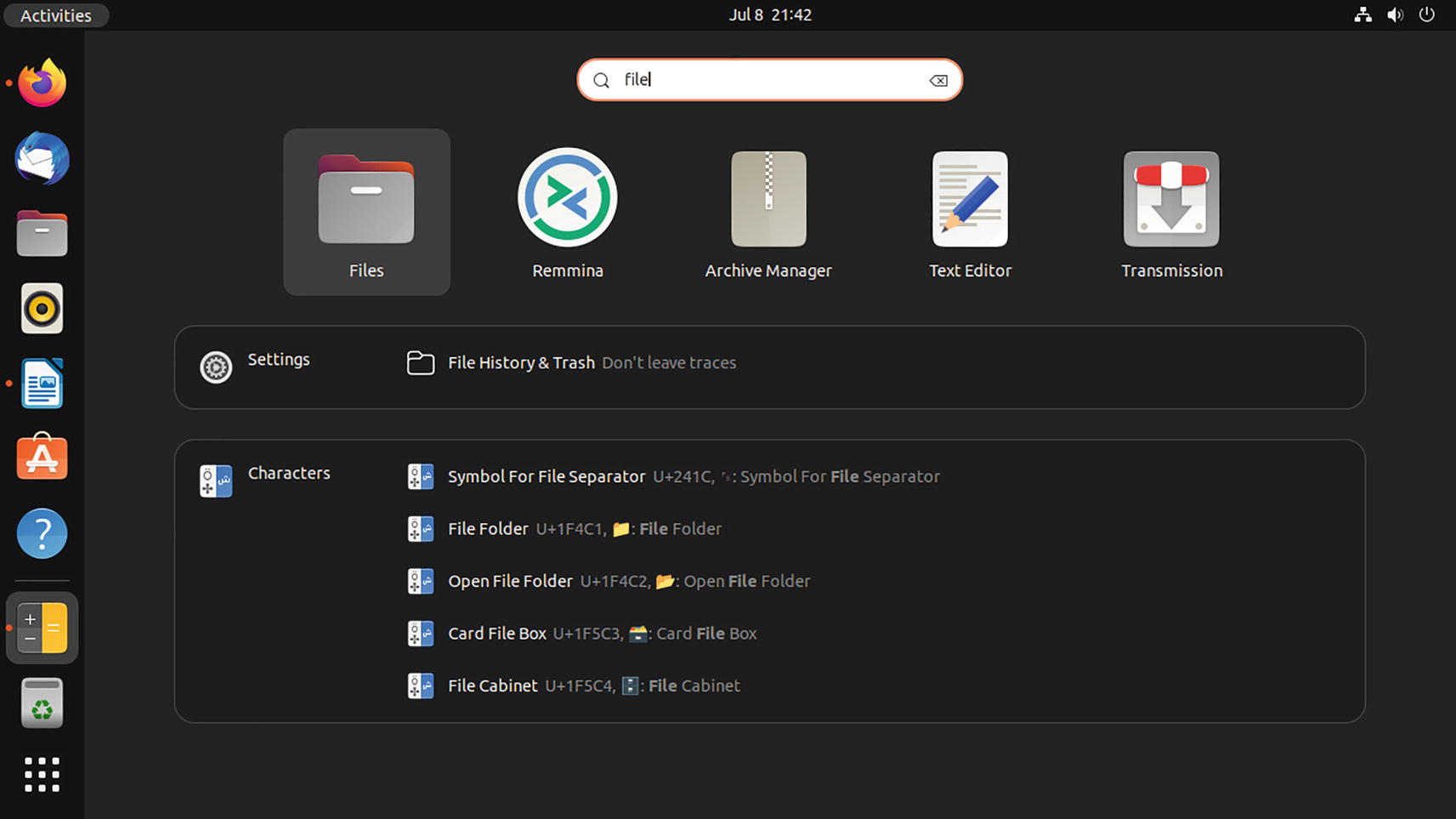

A screenshot of the activities search window on Ubuntu has the result of files, file history and trash in settings, and the characters that contain the word, file.

The Activities search will return many kinds of information

This search and the application grid , which you can access at the bottom of the Dock or by pressing Super+A, are the primary ways that you’ll start applications that you have not pinned to the Dock. In the application grid, you can scroll through multiple pages of apps by using the mouse wheel or clicking and dragging the mouse to the left and right (or, if you have a touch-sensitive display, by swiping to the left and right).

You can customize the application grid by dragging the icons around to rearrange them. Not only can you reorder the icons or drag them to different pages, you can also drag one icon on top of another to create an app folder, which you can name. For example, you can click on the Utilities folder to see how important but seldom-used applications are all grouped together to be easy to find without cluttering the application grid.

Clock, Calendar, and Notifications

A screenshot of the notification window on Ubuntu has the media playback controls, a calendar with the current date, and the upcoming scheduled meeting.

Ubuntu shows a calendar, upcoming meetings, and notifications such as media playback controls

Clicking on a notification will open the corresponding application. Some notifications are dynamic. For instance, Rhythmbox and Firefox will display playback controls for any media they are currently playing. Other applications can add relevant information as well. For instance, any additional time zones you add to Clocks will add the current local time for those time zones beneath the calendar. Likewise, if you install GNOME Weather, your local weather forecast for the next 5 hours will be displayed as well.

When you need to concentrate, you can click the “Do Not Disturb” switch at the bottom of the notification window. This will cause GNOME to hide any future notifications until you turn Do Not Disturb mode off.

System Menu and Indicators

The top right corner of your screen will show the System menu. This is dedicated to your computer’s hardware functions and your desktop preferences.

At the top of the System menu are volume control sliders. If you have speakers attached to your computer, you will be able to quickly adjust your computer’s volume. If an application is accessing your computer’s microphone, you will also see a slider for that as well. If the maximum volume is still low, you can open Settings, click “Sound” in the left side of the application, and turn on “Over-Amplification” to allow values over 100%. This can cause audio quality loss or damage to speakers, headphones, or your hearing, so use this option only when necessary.

The System menu offers an additional shortcut: move your mouse over the volume or microphone icon, and use the scroll wheel to quickly raise or lower your computer’s volume levels.

The next section of the System menu gives you access to hardware settings. Clicking on your wired network, your wireless network, or your Bluetooth icon will allow you to disable the hardware feature or open up Settings to that settings category.

Your current location or power savings status is also displayed, and if you are using GNOME’s Night Light feature to reduce blue light, you can disable it until tomorrow (or reenable it sooner), turn off the feature all together, or view your Night Light settings.

The last section allows you to quickly launch Settings for a comprehensive list of various preferences you can change, or lock your screen, which will also put your monitors in power-saving mode. Selecting “Power Off/Log Out” will let you close all applications and return to the login screen. You can also reboot your computer or completely power it down.

Certain applications will add indicator icons to your panel. These are displayed to the left of your System menu. The way you interact with these icons will vary from application to application. Most allow you to simply click on the icon to display a contextual menu with various commands. Sometimes middle-clicking an icon will open (or close) an application window. Most modern applications treat a left or a right mouse click as the same thing, but older software—especially software originally designed for Windows—will expect a right click before showing a menu. If you’ve spent a lot of time interacting with the little icons in Windows’ notification area (commonly but inaccurately called the “system tray”), then you’ll be at home in Ubuntu as well.

Customizing Ubuntu

A screenshot of the Settings window on Ubuntu. Appearance is selected from the panel on the left. It has options for style, color, size, position of new icons, and show personal folder slider.

You can quickly customize Ubuntu to suit your preferences

The Style section contains what will be the most popular settings for every reader. Ubuntu defaults to a light theme that gives a bright, clean look to the Ubuntu desktop and makes it really easy to see which application is currently focused. But dark themes are increasingly popular on phones, and Ubuntu’s dark theme keeps the Ubuntu interface from blinding you at night. Newer GNOME and GTK applications can detect your preferences and will automatically change their colors to provide a dark interface. Because this is a new feature, not all applications will automatically support dark mode.

In addition, Ubuntu offers ten pleasing accent colors for your desktop. If orange isn’t your style, you can pick a different color for your icons and menus. While the choices are limited, the new accent color feature in Ubuntu 22.04 LTS ensures that the theme will be compatible with older and newer applications.

Note that while I personally prefer dark mode on my own computer (since I’m a night owl), this book sticks with the default light mode because it makes the figures easier to read. Feel free to change these settings until you find a combination that you enjoy the most.

Other notable settings options are the Background settings. You can change your desktop’s background image, and note that that change you make will only apply to the current style you have activated: light or dark, so you can choose a different wallpaper for each style. Ubuntu comes with a color and grayscale background with the release’s mascot (Ubuntu 22.04 LTS is codenamed “Jammy Jellyfish”), and also includes an additional ten images voted on from a selection provided by the Ubuntu community for each release. You can also click “Add Picture…” on the header bar to choose your own picture.

“Displays” lets you manage your computer’s monitor settings, but the Night Light feature lets you turn on blue light reduction. You can schedule this to automatically activate between sunset and sunrise, or you can set a custom schedule. You’re also able to adjust how strong the effect is. As a writer, I use it as is, friends who create photos or other art avoid it altogether, but the choice is yours.

The last feature I want to highlight is the screen long feature. You can see this in Settings by clicking “Privacy,” and then “Screen”. By default, Ubuntu automatically locks your screen after 5 minutes of no keyboard or mouse activity. This is great for a laptop or business computer, but it’s a little aggressive for a home computer. You can set Ubuntu to set blank your screen (and put your monitor in power-saving mode) after a delay between 1 minute and 15 minutes. You can also tell Ubuntu to never blank your screen. By default, Ubuntu also locks your desktop session at the same time it blanks your display. You can add an additional delay of 30 seconds, a couple of minutes, half an hour, or 1 hour before your desktop session is automatically locked. While your screen is locked, running applications will continue to run just as before, but you will have to enter your password to regain access to your desktop session.

Ubuntu won’t blank your display while you are watching a video, and you can immediately lock your screen by pressing Super+l (lowercase l). Your desktop session will be locked until you enter your password on the lock screen.

Managing Windows

Every application is displayed inside a window . At the top of the window is either a traditional title bar (as in Windows or macOS) or a larger and more versatile “header bar,” which combines the functions of a title bar with a traditional menu bar and toolbar. You can move a window by dragging it by its title bar or header bar. Most application windows have three window controls on the right side of the title or header bar. In order, these hide (or minimize) the window, maximize the window to take up the entire screen, or close the window. Moving your mouse pointer to the window’s edge or corner allows you to resize the window to any size you like.

You can also resize windows by dragging a window to the top, left, or right of your screen. Dragging to the top of the screen maximizes a window. You can drag it down from the panel to restore the previous window size. Dragging a window to the left or the right snaps it to that half of the screen, and is perfect for displaying two windows side by side. If you snap one window to the left half of the screen and another to the right half of the screen, you can resize both windows at the same time by dragging their shared border. Dragging a snapped window away from the edge of the screen by its title bar or header bar restores the previous window size as well.

You can switch between windows by pressing Alt+Tab. If you continue holding Alt, the window switcher will appear, and you can choose any running application as long as you are holding Alt. Each time you press Tab, you will cycle forward through the list to the next running application. Releasing Alt when the desired application is highlighted will switch to that application. Alt+Shift+Tab moves in reverse. You can also click a displayed window icon with the mouse to switch to it while you are holding Alt.

If you have multiple windows open in the same application, you can easily switch between them by pressing Alt+` (backtick) on a US keyboard. If your keyboard layout is set to match your physical keyboard, you can press the leftmost key above the Tab key even if it is not the backtick key. The application switcher will display all open applications, with the current application’s windows below. This works the same as the window switcher, and Alt+Shift+` will move backward through the list. You can also use the arrow keys while holding Alt: Up to move to the application switcher, Down to display the application’s open windows, and left and right to move around. You can let go of Alt to select a window, or click a displayed window with your mouse.

Installing and Updating Software

Ubuntu is a comprehensive operating system. As discussed in the last chapter, the Ubuntu operating system consists of a Linux kernel, the standard GNU userspace, X or Wayland for the graphics display system, and tens of thousands of other Free Software and open source projects. All of the software that comes with Ubuntu has been built from its source code directly on Ubuntu and packaged for delivery and installation. (Technically, some proprietary software and drivers were not compiled by Ubuntu, but they are installed and updated in the same manner.) This includes not only the software included on your installation media and in a newly installed Ubuntu system but thousands upon thousands of other applications that are available from the Ubuntu software repositories.

Ubuntu also provides a variety of applications that are published especially for Ubuntu and other Linux distros as “snap” packages. These software applications are compatible with any supported version of Ubuntu, and updates come directly from the software developer, independent of Ubuntu’s release schedule. For the most part, you won’t need to worry about how the software has been prepared for you. Ubuntu software brings all these sources together in one place.

Ubuntu Software

A screenshot of the Ubuntu Software window has three tabs for explore, installed, and updates. Advertisements for software such as Jami, powershell, and more are given under the Explore tab.

Ubuntu Software provides a catalog with thousands of free applications

Ubuntu Software provides a look at thousands of software packages. Because the packages are located in the Ubuntu software repositories, it always downloads and installs the most up-to-date version of an application for the current Ubuntu release. In addition, anything installed will receive updates through the Software Updater along with all other software. This makes Ubuntu Software an easy way to install software, and will be the primary method of installation used for the rest of this book. Some software is not displayed in Ubuntu Software, and when this software is featured in this book, instructions for installing in a Terminal window will be given. You can see Chapter 6 for a full explanation of what it means to install software via the command line, and how it can be a faster way to install software if you know precisely what you are looking for.

Snaps

Ubuntu now uses the “snap” packages to allow third-party developers to offer their applications to Ubuntu users. Snaps are mostly restricted to their own files and data, which provides protection against undiscovered security flaws or undetected malicious software. Over time, more and more software will be available via snaps—including newer versions of software included in Ubuntu, like LibreOffice and VLC. These applications do not replace or conflict with Ubuntu-provided software and are automatically upgraded when newer versions are published. This means, for example, that Firefox on Ubuntu is provided directly by Mozilla!

Other Sources

If you download software for Ubuntu directly from a website, you’ll be provided with a .deb file. This is a Debian package file and is used by Debian and Ubuntu to allow your operating system to install and uninstall software cleanly by using the Debian package manager. You can simply double-click on the .deb file, and Ubuntu Software will open and display the information inside the Debian package. You can choose whether or not to install the software from that screen. With the exception of certain packages like Google Chrome and Steam, which add their own repositories to Ubuntu’s list of software repositories, software you install manually will not receive automatic updates with bug or security fixes and in any case have not been reviewed by Ubuntu developers, so make sure to only install software you trust.

Updating Ubuntu

A screenshot of the software updater window for Ubuntu has checkboxes for security updates and other updates along with remind me later and install now buttons.

Software Updater tells you about software updates. This is the detailed view

Your computer will check for Ubuntu updates on a daily basis. Once a week, Ubuntu will inform you about recommended updates . These updates will only provide maintenance updates to fix bugs, not major newer or “feature” releases of software. If security updates are available, Ubuntu will notify you immediately. Installing the updates is automatic once you click “Install Now” and only requires your password authorization to begin.

The Software Updater provides updates for all software contained in the Ubuntu repositories, and acts as a single way to make sure all of your applications are secure and up to date. All updates are signed and verified by the Ubuntu developers so you can be assured that updates are trustworthy.

A screenshot of a pop-up message reads, Pending update of snap-store snap. Close the app to avoid disruption, 13 days left. It has the date and time on the top.

Snaps cannot be updated while they are running. Ubuntu will notify you and check again later

If you receive a notification of a pending update, you can simply continue using the application. Just remember to close it when you’re done with it. Ubuntu will update it the next time it checks for updates to your computer’s snap packages. If it still hasn’t been able to update a running snap after 14 days, Ubuntu will forcibly close the application and begin the update process.

A screenshot of the Ubuntu software window has three tabs, explore, installed, and updates. The Updates tab has application and device firmware updates for Firefox and OptiPlex with buttons for update and update all.

Ubuntu Software can update snap packages, and often your computer’s firmware as well!

Simply click “Update” to download and install the latest update of your installed software. If your computer’s or devices’ manufacturer supports it, Ubuntu Software can install firmware and hardware updates as well. They will be listed separately and can be updated at your leisure.

Upgrading Ubuntu

A screenshot for the Ubuntu 24.10 upgrade window and the software updater window has options for do not upgrade, ask me later, upgrade now, settings, upgrade, and ok.

Upgrading to a new version of Ubuntu is simple

A new version of Ubuntu is released every 6 months: once in April and once in October. Every fourth release is supported for 5 years instead of 9 months (with an additional 5 years of support available with a free Ubuntu Pro subscription) and is considered a long-term support (LTS) release. Ubuntu 22.04 LTS is the release covered in this book, and the next LTS release will be Ubuntu 24.04 in April 2024.

When a new version of Ubuntu is released, the Software Updater will notify you of the available update. LTS releases, by default, will only notify you once the next LTS release is available, and only after a delay of 3 months when all updates are rolled into a “point” release (such as Ubuntu 22.04.1 LTS). This allows for any major bugs to be addressed, and postrelease updates to settle down with the help of early adopters. This allows you to enjoy a stable system at all times.

When you are notified of a newer version of Ubuntu, it’s important to install all updates still pending for your current release and back up your files. Once your software is up to date, you can click the “Upgrade...” button in the Software Updater . This will display the release notes for the new version of Ubuntu. After reading the release notes, you can choose to continue with the update. This is a lengthy process that downloads a very large amount of data and cannot be interrupted once it begins.

This upgrades all software on your computer with newer versions. For the most part, it actually uses the same methods as minor software updates—a testament to the power of Ubuntu’s software packaging systems. While it should be safe to browse the Web or play a simple game, you should make sure your system is plugged into AC power if you are upgrading a laptop, and refrain from doing any important work on your computer during the upgrade. Once finished, reboot immediately. Your system will restart and you will be running the new version of Ubuntu.

Managing User Accounts

Ubuntu was designed to handle multiple users on a single computer, and it is easy for each user to have his or her own account where each user’s settings and program data can be stored separately from the others’. While any installed applications are available to every user, application settings are stored in each user’s home folder. Things like mail, personal files, language settings, and desktop and wallpaper preferences are user-specific. Giving each computer user a dedicated account allows each user to use the computer without affecting other users’ experience. A user can even log in and use Ubuntu while another user’s programs continue running in the background!

A screenshot of the Settings window on Ubuntu. Users is selected from the panel on the left. It has options for password and account activity under authentication and login with the user name at the top.

User Accounts is where accounts can be added, removed, and modified

Adding, removing, or changing other user accounts modifies the operating system’s settings, and requires administrative access. You can click the “Unlock” button near the top right of the window. You will be prompted for your password, and then you will be able to modify other user accounts. (If you are not using an account with administrative privileges, you can select an account that does have administrative privileges and provide that account’s password instead.) The applet will automatically lock again after 15 minutes of disuse. The “Add User...” and “Remove User...” buttons also become available.

A screenshot of the Add user dialog box from the Users option under Settings. It has options for account type, full name, username, and password. The drop-down menu for username has various names.

A new account can be added to the computer in seconds

The new account needs a password. By default, Ubuntu will simply prompt the user to create a secure password the first time they log in. You can also set a secure password before creating the account. Once you have decided how to handle the password, click the green “Add” button in the window’s header bar.

Finding Things in Ubuntu Instead of Windows

A screenshot of the Windows 11 desktop has the Microsoft Edge browser opened. Shortcuts for Recycle Bin and Microsoft Edge are on the left.

A typical Windows 11 desktop with one web browser window open

Here are some guidelines that should help you make the transition:

The Windows Taskbar is replaced by the Ubuntu Dock on the left side of the screen. The Dock can be moved to the bottom or right of the screen, and the icons can be resized in Settings, under Appearance. The system notification area (sometimes called the system tray) on the right side of the Windows Taskbar is similar to the indicator icons at the top right corner of the screen in Ubuntu. The Action Center in Windows 11 is duplicated by the Notification window at the top center of Ubuntu’s desktop.

The Start Menu and Start Screen are replaced by the Activities overview search and the application grid. File search is provided by both the Activities overview and by running the Files application and pressing Ctrl+F. The Control Panel and Settings apps are replaced by the Settings application. Task Manager is replaced by System Monitor available in the application grid.

Changing the desktop wallpaper image can be performed by right-clicking the desktop and choosing “Change Background....” The theme and accent colors can be changed via Settings ➤ Appearance. Custom themes are not supported by Ubuntu or GNOME and require third-party software. An accessible, high-contrast theme is available in Settings ➤ Accessibility by enabling the “High Contrast” option.

Windows are controlled similarly in both Windows and Ubuntu. The system menu in Windows is accessed by clicking the window icon or the top left corner of the title bar, and in Ubuntu it can be accessed by pressing Alt+Space or right-clicking a title bar in Ubuntu.

The Windows File Explorer file manager is replaced by the Nautilus file manager, labeled “Files” in the Ubuntu Dock and application grid. The C: drive in reference to the system drive is known as the root directory. Disks and external storage drives are not assigned drive letters but are mounted inside the existing file system, usually under /media/username. Folders are often referred to by the older term “directory”—especially on the command line. The user folder is known as the home folder. Hidden files begin with a . (period) and are often called “dot-files.” The Windows registry is replaced by a combination of text configuration files, often in /etc for system-wide settings and dot-files in each user’s home folder for user-specific settings, usually in a hidden directory such as .mozilla or .config.

The functionality of the Microsoft Store is provided by Ubuntu Software. Windows Update and updates from the Microsoft Store are replaced by Software Updater, which tracks maintenance and security updates for all applications installed via Ubuntu Software or otherwise installed from the Ubuntu software repositories (such is as on the command line with apt). Third-party applications installed as snap packages are updated automatically.

Finding Things in Ubuntu Instead of macOS

A screenshot of the mac O S desktop has a web browser window opened.

A typical macOS desktop one Web browser window open

The Option key is used for Alt but is also sometimes referred to as Meta. These names refer to modifier keys used on Unix terminals long before Mac OS or OS X existed. The Command key is used for the Super key.

The Dock is replaced by the Ubuntu Dock on the left side of the screen. The Ubuntu Dock can be moved to the bottom or right of the screen, and the icons can be resized in Settings, under Appearance. The menu bar extras are similar to the indicator icons at the top right corner of the screen in Ubuntu.

Launchpad is replaced by the Activities overview and application grid. Spotlight-like file search functionality is provided by the Activities overview, and File search is provided by running the Files application and pressing Ctrl+F. System Preferences is replaced by the Settings menu under the application grid or System menu. Activity Manager is replaced by System Monitor in the application grid.

The Apple Menu is replaced by the System menu at the top right of the screen.

Changing the desktop wallpaper image can be performed by right-clicking the desktop and choosing “Change Background....” The theme and accent colors can be changed via Settings ➤ Appearance. Custom themes are not supported by Ubuntu or GNOME and require third-party software. An accessible, high-contrast theme is available in Settings ➤ Accessibility by enabling the “High Contrast” option.

Windows are controlled similarly in both macOS and Ubuntu. The Maximize control in Ubuntu functions like the full-screen control in macOS. Additional window controls in Ubuntu can be accessed by pressing Alt+Space or right-clicking a title bar. In Ubuntu, the App Menu features can sometimes be found by right-clicking the application’s Launcher icon as well as clicking the Application menu.

Finder is replaced by the Nautilus file manager, labeled “Files” in the Ubuntu Dock and application grid. The Mac drive in reference to the system drive is known as the root directory. Disk and storage drives are mounted in the existing file system, usually under /media/username. Folders are often referred to as directories—especially on the command line. The user folder is known as the home folder.

The functionality of the App Store is provided by Ubuntu Software. Software Update and automatic updates from the App Store are replaced by Software Updater, which tracks maintenance and security updates for all applications installed via Ubuntu Software or otherwise installed from the Ubuntu software repositories (such as on the command line with apt). Third-party applications installed as snap packages are updated automatically.

Connecting to a Windows Desktop Remotely

You may find it useful to run Windows programs during your transition to Ubuntu, or you may want to use Windows-only programs from time to time. Luckily, Ubuntu comes with a remote desktop client preinstalled. Remmina Remote Desktop Client can connect to other computers in a variety of different ways, including Remote Desktop Connection, VNC, and SSH. Remote Desktop Connection (also known as Terminal Services) is available in Windows 10 Pro and higher editions, and SSH is available in all Unix- or Linux-based operating systems. In order to connect to a computer remotely, it must be powered on and not sleeping or hibernating.

Your first step is to set up your Windows system to accept remote desktop connections. This is fairly simple, and you can do so by right-clicking Computer or This PC in the Start Menu or File Explorer and choosing “Properties” from the context menu. When the System Properties window appears, you can click the “Remote” tab or the “Remote desktop” option and make sure that the “Allow remote connections to this computer” or “Remote Desktop” option is enabled. If you have trouble logging in, make sure that “Allow connections only from computers running Remote Desktop with Network Level Authentication” (recommended) is unchecked. In Windows 11, you can access this setting by clicking the down arrow next to the “Remote Desktop” feature switch.

You can run Remmina by searching for its name or “remote desktop” in the application grid. The first time you run Remmina, it will display a window with an empty list of remote computers. You can save various profiles for connecting to remote computers and double-click them in the future. To begin, click the “New connection profile” icon at the top left of the header bar. To set up a connection to a Windows computer, you’ll need to know the IP address of the computer or the host name if your router supports Windows host name resolution. You’ll put this in the Server field, and you can also enter your Windows username and password to the profile to save time when connecting. If you are connecting over the Internet, consider keeping the color depth at 256, but if you are connecting to another computer on the same network, you may want to increase the color depth to 16-, 24-, or even 32-bit color.

2 adjacent screenshots of the Windows 11 remote connection in Ubuntu. The one on the left has the options for the remote connection profile dialog box, while the one on the right has the Windows 11 O S connected remotely.

You can connect to remote Windows machines and use them with ease

The toolbar on the left allows you to scale the display to match the size of your Remmina window (“Toggle dynamic resolution update”) or enter full-screen mode (Right Ctrl+s) and focus on Windows only. You can customize these options in the toolbar or in the connection preferences to tune the experience to your preferences.

Sharing Office Documents with Others

On Ubuntu , you’ll start off with LibreOffice. This full-featured office software is more than capable of opening, editing, and saving Microsoft Office documents. But by default it uses the Open Document Format to save its files in. This standard format is now supported by all modern office software, but legacy office software may have limited support.

LibreOffice supports saving files in many various formats. By default, an edited document will be saved in its original format. However, you may find it convenient to offer files in different formats to ensure an optimal viewing experience for others.

In LibreOffice, you can choose “Save As...” from the File menu. You can either type a file name with a standard extension (“.odt” for Open Document Text format, “.doc” for Word 97 format, “.docx” for Microsoft Word 2007 XML format, “.html” for HTML, and so on) or choose a specific format from the drop-down list under the folder view. Clicking Save will save a copy of the document and continue saving under the new filename and format. Word formats are useful for sharing files that must be edited by users with Microsoft Office, which may have limited support for the Open Document format.

If you would like to ensure that the other user can view and print a document precisely as you formatted it, but you do not need or want them to edit it, you can save a copy of the file as a PDF. This is available via the “Export as PDF...” option under the File menu in LibreOffice, and will create a file that represents a printed document that can be viewed and printed by others on any operating system with a PDF viewer.

In producing this book, my editors needed Word 2010-format documents and provided Word template files. However, I don’t own a modern copy of Microsoft Word and use Ubuntu exclusively. I opened the template in LibreOffice and saved it in Open Document Text format and started typing. When I finished a chapter, I would save it as Microsoft Word 2007–2013 XML (DOCX) format and send it to my editors. Each of us was able to use our preferred tools to deliver this book into your hands.

Sharing Photos and Graphics with Others

Graphics images are among the easiest files to share between operating systems, as the Internet has seen to it that the most common and useful file formats are supported and shared between all modern operating systems. Therefore, most formats should work without issue. I will simply add a note about each of the most common file formats.

JPG files are the most common format around. This is a “lossy” format, which means that it saves space by not encoding all of the data perfectly when it’s compressed. This format is designed for real-world photographs and takes advantage of how the human eye works. This does mean that editing and saving JPG files results in a slight loss of quality that can build up over time. For a finished photograph that does not need to be edited more than once or twice, JPG is the clear winner. For art with large single-color fields or line art, the compression can interfere with the image quality.

GIF is a fairly ancient file format that was developed to be easy for the slow computers available in 1987 to process. GIFs have only 256 colors, and therefore tend to be low quality, but they are often used online to show short animations. For any other purpose, they are a bad choice, even if they work everywhere.

PNG was developed as a response to a patent lawsuit regarding the GIF format, and is probably the most versatile image format around today. With good lossless compression, the resulting files are not subject to quality loss over multiple edits, and while photographs result in much larger file sizes in JPG, line art is much smaller and more crisp than GIF. This is a perfect format for works in progress and can be opened in almost every image browser.

TIFF was an early black and white-only format that was developed as a common format for desktop document scanners. It is still often seen as a format for scanners and faxes. While the format became quite versatile for grayscale and color documents and can flexibly hold lots of notes and other information about a scanned document and can even use JPEG compression for documents, it’s probably better to choose JPG for a final file or PNG for a file that will be edited by others.

Formatting Disks to Work with Other Operating Systems

Computers store data on hard disks, floppy disks, CD, DVD, and Blu-ray discs, magnetic audio tape, paper tape, solid-state disks, and flash memory, and the physical formats have changed tremendously since the 1940s. The logical formats have changed even more rapidly. I’ll use an analogy to help illustrate how computers and disks work.

A disk is like a ruled piece of paper. You might have a single sheet or various sizes of notepads. They can be opened and viewed by anyone. Internal and external hard disks, optical discs, and media cards are all like a notepad.

When you write in a physical notepad, the notepad doesn’t really care what you write. You can write in English or German. Japanese kana represents sounds. Hebrew characters represent sounds but are written from right to left. Chinese ideograms represent ideas. All of these can be written between the lines on the same notepad. But only some of these ways of writing will make sense to readers. These writing systems are like the disk format and file system, and the readers are like the operating system.

The first Windows and Mac computers were typically used in offline, homogeneous environments. This meant that in the days before networking was widespread, Microsoft and Apple were free to develop their own way of reading and writing data to a disk in a manner that was efficient and supported the way their software worked. For this reason, Windows computers first supported only FAT file systems written to a nonpartitioned or MBR-formatted disk. Mac computers supported HFS file systems on a full or Apple Partition Map-formatted disk. As their needs became more complex, Windows computers began supporting NTFS and GPT, and Apple computers began supporting FAT and NTFS so they could read and write Windows-formatted disks, and started using HFS+, APFS, and GPT. But priority was given to the native file formats on each system.

Linux grew up in a networked world where it needed to read a lot of different file formats. So while the Linux “extended file system” was developed to serve its needs better than the Minux file system it started with and Ubuntu today uses the fourth version of this system, ext4fs, Linux also often needed to read Windows- and Mac-formatted disks. This resulted in rich file system support that Ubuntu users benefit from today. The upside is that Ubuntu can read almost any disk format that it sees. But Windows and macOS are still very limited in the formats that they support. Here are some tips for formatting disks so that they can be used on Windows and Mac computers.

Both Windows and macOS can read MBR- and GPT-formatted disks. MBR is good for small media devices, but GPT should be used for any system hard drive you install Ubuntu to, and is required for drives larger than 2.1 TB. Apple Partition Map can only be read by macOS and Ubuntu, and has been replaced by GPT on macOS.

File system support is trickier. The only format that Windows and OS X both support for reading as well as writing is FAT32. This format can be read in almost any consumer device on the market, but can be prone to corruption if a computer or device loses power while writing, and also has a file size limit of approximately 4 GB. Especially for video and backup files, this can be restricting.

The native Windows format is NTFS, and Ubuntu can read and write this format reliably. However, OS X can only read NTFS and not write to it. For sharing between Windows and Ubuntu computers, however, this is a very robust and reliable format.

The native macOS format is APFS. Ubuntu doesn’t have trouble reading the previous default format HPFS+, but Ubuntu can’t read APFS-formatted disks without installing additional software, and cannot write to them at all. Windows cannot read either disk format without third-party software.

With this maze of compatibility issues, FAT32 and NTFS remain the best choices for USB drives and portable hard drives.

The write-once-only nature of early optical discs posed special problems, and therefore early CD-ROMs used a file system called ISO 9660. This was extended in a few different ways to support long file names and was eventually replaced by UDF, or Universal Disc Format. The upside is that CD, DVD, and Blu-ray data discs use these formats exclusively. This means that optical discs can be read by any computer with a compatible disc drive. So you’ll never need to worry about formats—your burning software will take care of that decision.

Summary

Using a new operating system can be very much like living in a different part of the world with different customs: much is still familiar, and just a little bit of context can make your environment much more comprehensible.

Ubuntu has its own strengths and works very well with others. Whether you move to Ubuntu only or use it along with other operating systems, Ubuntu is flexible enough to work with other computers over the network or via floppy disk. Armed with this knowledge, you’re ready to begin using Ubuntu as a part of your everyday routine.