Chapter 21

Application Localization

At the time of this writing, the iPhone is available in more than 90 different countries, and that number will continue to increase over time. You can now buy and use an iPhone on every continent except Antarctica. The iPad was held back a bit, as Apple struggled to satisfy demand in what it considered the most important countries first, but now the iPad is also sold all over the world and is nearly as ubiquitous as the iPhone.

If you plan on releasing applications through the App Store, your potential market is considerably larger than just people in your own country who speak your own language. Fortunately, iOS has a robust localization architecture that lets you easily translate your application (or have it translated by others) into not only multiple languages, but even into multiple dialects of the same language. Do you want to provide different terminology to English speakers in the United Kingdom than you do to English speakers in the United States? No problem.

That is, localization is no problem if you’ve written your code correctly. Retrofitting an existing application to support localization is much harder than writing your application that way from the start. In this chapter, we’ll show you how to write your code so it is easy to localize, and then we’ll go about localizing a sample application.

Localization Architecture

When a nonlocalized application is run, all of the application’s text will be presented in the developer’s own language, also known as the development base language.

When developers decide to localize their application, they create a subdirectory in their application bundle for each supported language. Each language’s subdirectory contains a subset of the application’s resources that were translated into that language. Each subdirectory is called a localization project, or localization folder. Localization folder names always end with the extension .lproj.

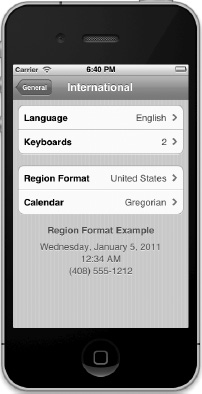

In the iOS Settings application, the user has the ability to set the device’s preferred language and region format. For example, if the user’s language is English, available regions might be United States, Australia, and Hong Kong—all regions in which English is spoken.

When a localized application needs to load a resource—such as an image, property list, or nib—the application checks the user’s language and region and looks for a localization folder that matches that setting. If it finds one, it will load the localized version of the resource instead of the base version.

For users who selected French as their iOS language and France as their region, the application will look first for a localization folder named fr_FR.lproj. The first two letters of the folder name are the ISO country code that represents the French language. The two letters following the underscore are the ISO code that represents France.

If the application cannot find a match using the two-letter code, it will look for a match using the language’s three-letter ISO code. In our example, if the application is unable to find a folder named fr_FR.lproj, it will look for a localization folder named fre_FR or fra_FR.

All languages have at least one three-letter code. Some have two three-letter codes: one for the English spelling of the language and another for the native spelling. Only some languages have two-letter codes. When a language has both a two-letter code and a three-letter code, the two-letter code is preferred.

NOTE: You can find a list of the current ISO country codes on the ISO web site (http://www.iso.org/iso/country_codes.htm). Both the two- and three-letter codes are part of the ISO 3166 standard.

If the application cannot find a folder that is an exact match, it will then look for a localization folder in the application bundle that matches just the language code without the region code. So, staying with our French-speaking person from France, the application next looks for a localization project called fr.lproj. If it doesn’t find a language project with that name, it will look for fre.lproj, then fra.lproj. If none of those are found, it checks for French.lproj. The last construct exists to support legacy Mac OS X applications, and generally speaking, you should avoid it.

If the application doesn’t find a language project that matches either the language/region combination or just the language, it will use the resources from the development base language. If it does find an appropriate localization project, it will always look there first for any resources that it needs. If you load a UIImage using imageNamed:, for example, the application will look first for an image with the specified name in the localization project. If it finds one, it will use that image. If it doesn’t, it will fall back to the base language resource.

If an application has more than one localization project that matches—for example, a project called fr_FR.lproj and one called fr.lproj—it will look first in the more specific match, which is fr_FR.lproj in this case. If it doesn’t find the resource there, it will look in fr.lproj. This gives you the ability to provide resources common to all speakers of a language in one language project, localizing only those resources that are impacted by differences in dialect or geographic region.

You should choose to localize only those resources that are affected by language or country. For example, if an image in your application has no words and its meaning is universal, there’s no need to localize that image.

Strings Files

What do you do about string literals and string constants in your source code? Consider this source code from the previous chapter:

UIAlertView *alert = [[UIAlertView alloc]

initWithTitle:@"Error accessing photo library"

message:@"Device does not support a photo library"

delegate:nil

cancelButtonTitle:@"Drat!"

otherButtonTitles:nil];

[alert show];

If you’ve gone through the effort of localizing your application for a particular audience, you certainly don’t want to be presenting alerts written in the development base language. The answer is to store these strings in special text files called strings files.

What’s in a Strings File?

Strings files are nothing more than Unicode (UTF-16) text files that contain a list of string pairs, each identified by a comment. Here is an example of what a strings file might look like in your application:

/* Used to ask the user his/her first name */

"First Name" = "First Name";

/* Used to get the user's last name */

"Last Name" = "Last Name";

/* Used to ask the user's birth date */

"Birthday" = "Birthday";

The values between the /* and the */ characters are just comments for the translator. They are not used in the application, and you could skip adding them, though they’re a good idea. The comments give context, showing how a particular string is being used in the application.

You’ll notice that each line lists the same string twice. The string on the left side of the equal sign acts as a key, and it will always contain the same value, regardless of language. The value on the right side of the equal sign is the one that is translated to the local language. So, the preceding strings file, localized into French, might look like this:

/* Used to ask the user his/her first name */

"First Name " = "Prénom";

/* Used to get the user's last name */

"Last Name " = "Nom de famille";

/* Used to ask the user's birth date */

"Birthday" = "Anniversaire";

The Localized String Macro

You won’t actually create the strings file by hand. Instead, you’ll embed each localizable text string in a special macro in your code. Once your source code is final and ready for localization, you’ll run a command-line program, named genstrings, which will search all your code files for occurrences of the macro, pulling out all the unique strings and embedding them in a localizable strings file.

Let’s see how the macro works. First, here’s a traditional string declaration:

NSString *myString = @"First Name";

To make this string localizable, do this instead:

NSString *myString = NSLocalizedString(@"First Name",

@"Used to ask the user his/her first name");

The NSLocalizedString macro takes two parameters:

- The first parameter is the string value in the base language. If there is no localization, the application will use this string.

- The second parameter is used as a comment in the strings file.

NSLocalizedString looks in the application bundle inside the appropriate localization project for a strings file named localizable.strings. If it does not find the file, it returns its first parameter, and the string will appear in the development base language. Strings are typically displayed only in the base language during development, since the application will not yet be localized.

If NSLocalizedString finds the strings file, it searches the file for a line that matches the first parameter. In the preceding example, NSLocalizedString will search the strings file for the string "First Name". If it doesn’t find a match in the localization project that matches the user’s language settings, it will then look for a strings file in the base language and use the value there. If there is no strings file, it will just use the first parameter you passed to the NSLocalizedString macro.

Now that you have an idea of how the localization architecture and the strings file work, let’s take a look at localization in action.

Real-World iOS: Localizing Your Application

We’re going to create a small application that displays the user’s current locale. A locale (an instance of NSLocale) represents both the user’s language and region. It is used by the system to determine which language to use when interacting with the user, as well as how to display dates, currency, and time information, among other things. After we create the application, we will then localize it into other languages. You’ll learn how to localize nib files, strings files, images, and even your application’s display name.

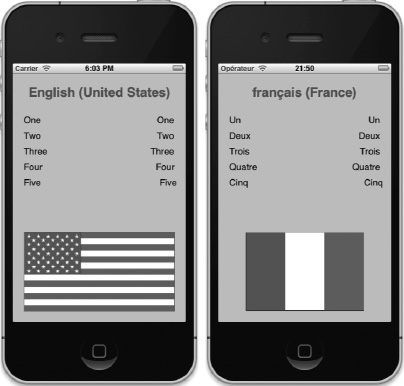

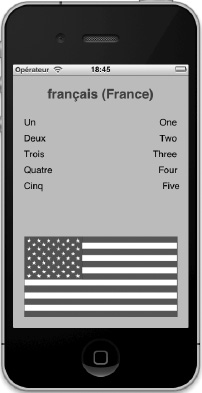

You can see what our application is going to look like in Figure 21–1. The name across the top comes from the user’s locale. The words down the left side of the view are static labels that are set in the nib file. The words down the right side are set programmatically using outlets. The flag image at the bottom of the screen is a static UIImageView.

Figure 21–1. The LocalizeMe application shown with two different language/region settings

Let’s hop right into it.

Setting Up LocalizeMe

Create a new project in Xcode using the Single View Application template, and call it LocalizeMe.

If you look in the source code archive, within the 21 - LocalizeMe folder, you’ll see a folder named Images. Inside that folder, you’ll find a pair of folders, one named English and one named French, each containing a file named flag.png. One version of the flag is the US flag, and the other is the French flag.

Start by dragging the English language version of flag.png into the project navigator’s LocalizeMe folder. When prompted, add a copy of that file to the project. We’ll get to the French version of that file as we make our way through the chapter.

Now let’s add some label outlets to the project. We need to create outlets to a total of six labels: one for the blue title across the top of the view, and five for the words down the right-hand side (see Figure 21–1). Select BIDViewController.h, and make the following changes:

#import <UIKit/UIKit.h>

@interface BIDViewController : UIViewController

@property (weak, nonatomic) IBOutlet UILabel *localeLabel;

@property (weak, nonatomic) IBOutlet UILabel *label1;

@property (weak, nonatomic) IBOutlet UILabel *label2;

@property (weak, nonatomic) IBOutlet UILabel *label3;

@property (weak, nonatomic) IBOutlet UILabel *label4;

@property (weak, nonatomic) IBOutlet UILabel *label5;

@end

Now select the BIDViewController.xib file to edit the GUI in Interface Builder. Make sure the View window is visible, and then drag a Label from the library, dropping it at the top of the view, aligned with the top blue guideline. Resize the label so that it takes the entire width of the view, from blue guideline to blue guideline. With the label selected, open the attributes inspector. Look for the Font control, and click the small T icon it contains to bring up a small font-selection popup. Click System Bold to let this title label stand out a bit from the rest. Then use the attributes inspector to set the text alignment to centered, and set the text color to a bright blue. You can also use the font selector to make the font size larger if you wish. As long as Autoshrink is selected in the object attributes inspector, the text will be resized if it gets too long to fit.

With your label in place, control-drag from the File’s Owner icon to this new label, and select the localeLabel outlet.

Next, drag five more Labels from the library, and put them against the left margin using the blue guideline, one above the other (see Figure 21–1). Resize the labels so they go about halfway across the view, or a little less. Double-click the top one, and change it from Label to One. Repeat this procedure with the other four labels, changing the text to the numbers Two through Five.

Drag five more Labels from the library, this time placing them against the right margin. Change the text alignment using the object attributes inspector so that they are right-aligned, and increase the size of the label so that it stretches from the right blue guideline to about the middle of the view. Control-drag from File’s Owner to each of the five new labels, connecting each one to a different numbered label outlet. Now, double-click each one of the new labels, and delete its text. We will be setting these values programmatically.

Finally, drag an Image View from the library over to the bottom part of the view so it touches the bottom and left blue guidelines. In the attributes inspector, select flag.png for the view’s Image attribute, and resize the image to stretch from blue guideline to blue guideline. In the attributes inspector, change the Mode attribute from its current value to Aspect Fit. Not all flags have the same aspect ratio, and we want to make sure the localized versions of the image look right. Selecting this option will cause the image view to resize any other images put in this image view so they fit, but it will maintain the correct aspect ratio (ratio of height to width). Finally, make the flag bigger, until it hits the right-side blue guideline.

Save your nib. Then switch to BIDViewController.m, and insert the following code at the top of the file:

#import "BIDViewController.h"

@implementation BIDViewController

@synthesize localeLabel;

@synthesize label1;

@synthesize label2;

@synthesize label3;

@synthesize label4;

@synthesize label5;

.

.

.

Now, provide the following implementation for the viewDidLoad method:

- (void)viewDidLoad

{

[super viewDidLoad];

// Do any additional setup after loading the view, typically from a nib.

NSLocale *locale = [NSLocale currentLocale];

NSString *displayNameString = [locale

displayNameForKey:NSLocaleIdentifier

value:[locale localeIdentifier]];

localeLabel.text = displayNameString;

label1.text = NSLocalizedString(@"One", @"The number 1");

label2.text = NSLocalizedString(@"Two", @"The number 2");

label3.text = NSLocalizedString(@"Three", @"The number 3");

label4.text = NSLocalizedString(@"Four", @"The number 4");

label5.text = NSLocalizedString(@"Five", @"The number 5");

}

Also, add the following code to the existing viewDidUnload method:

- (void)viewDidUnload

{

[super viewDidUnload];

// Release any retained subviews of the main view.

// e.g. self.myOutlet = nil;

self.localeLabel = nil;

self.label1 = nil;

self.label2 = nil;

self.label3 = nil;

self.label4 = nil;

self.label5 = nil;

}

The only item of note in this class is the viewDidLoad method. The first thing we do there is get an NSLocale instance that represents the user’s current locale, which can tell us both the user’s language and region preferences, as set in the iPhone’s Settings application.

NSLocale *locale = [NSLocale currentLocale];

The next line of code might need a bit of explanation. NSLocale works somewhat like a dictionary. It can give you a whole bunch of information about the current user’s preferences, including the name of the currency and the expected date format. You can find a complete list of the information that you can retrieve in the NSLocale API reference.

In this next line of code, we’re retrieving the locale identifier, which is the name of the language and/or region that this locale represents. We’re using a function called displayNameForKey:value:. The purpose of this method is to return the value of the item we’ve requested in a specific language.

The display name for the French language, for example, is Français in French, but French in English. This method gives you the ability to retrieve data about any locale so that it can be displayed appropriately to any users. In this case, we’re getting the display name for the locale in the language of that locale, which is why we pass [locale localeIdentifier] in the second argument. The localeIdentifier is a string in the format we used earlier to create our language projects. For an American English speaker, it would be en_US, and for a French speaker from France, it would be fr_FR.

NSString *displayNameString = [locale

displayNameForKey:NSLocaleIdentifier

value:[locale localeIdentifier]];

Once we have the display name, we use it to set the top label in the view.

localeLabel.text = displayNameString;

Next, we set the five other labels to the numbers one through five spelled out in our development base language. We also provide a comment telling what each word is. You can just pass an empty string if the words are obvious, as they are here, but any string you pass in the second argument will be turned into a comment in the strings file, so you can use this comment to communicate with the person doing your translations.

label1.text = NSLocalizedString(@"One", @"The number 1");

label2.text = NSLocalizedString(@"Two", @"The number 2");

label3.text = NSLocalizedString(@"Three", @"The number 3");

label4.text = NSLocalizedString(@"Four", @"The number 4");

label5.text = NSLocalizedString(@"Five", @"The number 5");

Let’s run our application now.

Trying Out LocalizeMe

You can use either the simulator or a device to test LocalizeMe. The simulator does seem to cache some language and region settings, so you may want to run the application on the device if you have that option. Once the application launches, it should look like Figure 21–2.

Figure 21–2. The language running under the authors’ base language. Our application is set up for localization but is not yet localized.

By using the NSLocalizedString macros instead of static strings, we are ready for localization, but we are not localized yet. If you use the Settings application on the simulator or on your iPhone to change to another language or region, the results look essentially the same, except for the label at the top of the view (see Figure 21–3).

Figure 21–3. The nonlocalized application run on an iPhone set to use the French language in France

Localizing the Nib

Now, let’s localize the nib file. The basic process for localizing any file is the same. In Xcode, single-click BIDViewController.xib, and then select View ![]() Utilities

Utilities ![]() Show File Inspector to bring up the file inspector to see detailed information for the nib file.

Show File Inspector to bring up the file inspector to see detailed information for the nib file.

CAUTION: Xcode will allow you to localize pretty much any file in the navigator. Just because you can, doesn’t mean you should. Never localize a source code file. Doing so will cause compile errors, as multiple object files with the same name will be created.

Look for the Localization section of the file inspector. You’ll see that it shows a single localization: English. Click the plus (+) button at the bottom of the Localization section, and select French (fr) from the popup list that appears (see Figure 21–4).

Figure 21–4. The file inspector showing localization and other information for BIDViewController.xib

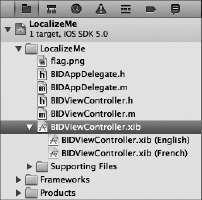

After adding a localization, take a look at the project navigator. Notice that the BIDViewController.xib file now has a disclosure triangle next to it, as if it were a group or folder. Expand it, and take a look (see Figure 21–5).

Figure 21–5. Localizable files have a disclosure triangle and a child value for each language or region you add.

In our project, BIDViewController.xib is now shown as a group containing two children: one tagged as English and one as French. The English version was created automatically when you created the project, and it represents your development base language.

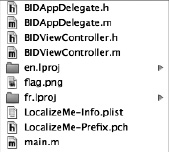

Each of these files lives in a separate folder, one called en.lproj and one called fr.lproj. Go to the Finder, and open the LocalizeMe folder within your LocalizeMe project folder. In addition to all your project files, you should see folders named en.lproj and fr.lproj (see Figure 21–6).

Figure 21–6. From the outset, our Xcode project included a language project folder for our base language. When we chose to make a file localizable, Xcode created a language project folder for the language we selected as well.

Note that the en.lproj folder was there all along, with its copy of BIDViewController.xib inside it all the while. When Xcode finds a resource that has exactly one localized version, it displays it as a single item. As soon as a file has two or more localized versions, they’re displayed as a group.

TIP: When dealing with locales, language codes are lowercase, but country codes are uppercase. So, the correct name for the French language project is fr.lproj, but the project for Parisian French (French as spoken by people in France) is fr_FR.lproj, not fr_fr.lproj or FR_fr.lproj. The iOS file system is case-sensitive, so it is important to match case correctly.

When you asked Xcode to create the French localization, Xcode created a new localization project in your project folder called fr.lproj and placed a copy of BIDViewController.xib in that folder. In Xcode’s project navigator, BIDViewController.xib should now have two children: English and French. Select French to open the nib file that will be shown to French speakers.

The nib file that opens in Interface Builder will look exactly like the one you built earlier, because the nib file you just created is a copy of the earlier one. Any changes you make to this file will be shown to people who speak French. Double-click each of the labels on the left side and change them from One, Two, Three, Four, and Five to Un, Deux, Trois, Quatre, and Cinq. Then save the nib.

Your nib is now localized in French. Compile and run the program. After it launches, tap the home button.

If you’ve already changed your Settings to the French region and language, you should see your translated labels on the left. For those folks who are a bit unsure about how to make those changes, we’ll walk you through it.

In the simulator, go to the Settings application, and select the General row and then the row labeled International. From here, you’ll be able to change your language and region preferences (see Figure 21–7).

Figure 21–7. Changing the language and region—the two settings that affect the user’s locale

You want to change the Region Format first, because once you change the language, iOS will reset and return to the home screen. Change the Region Format from United States to France (first select French, then select France from the new table that appears), and then change Language from English to Français. Click the Done button, and the simulator will reset its language. Now, your phone is set to use French.

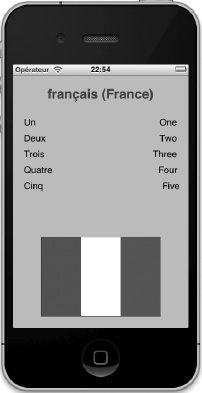

Run your app again. This time, the words down the left-hand side should show up in French (see Figure 21–8). But the flag and right column of text are still wrong. We’ll take care of the flag first.

Figure 21–8. The application is partially translated into French now.

Localizing an Image

We could change the flag image directly in the nib by just selecting a different image for the image view in the French localized nib file. Instead of doing that, we’ll actually localize the flag image itself.

When an image or other resource used by a nib is localized, the nib will automatically show the correct version for the language (though not for the dialect, at the time of this writing). If we localize the flag.png file itself with a French version, the nib will automatically show the correct flag when appropriate.

First, quit the simulator and make sure your application is stopped. Back in Xcode, single-click flag.png in the project navigator. Next, bring up the file inspector, and locate the Localization section, which you’ll see is currently empty. Make sure flag.png is still selected, and then press the + button at the bottom of the Localization section. Xcode will add an English localization for the file and move flag.png into the en.lproj folder (check the Finder to see this for yourself).

NOTE: In the current version of Xcode 4.2, there seems to be a slight bug in the GUI that shows up here. With flag.png selected, clicking the + button as we just described causes the file to be deselected, which makes the inspector suddenly pop into a no selection state. But don’t worry; it has done its work properly anyway. Just select flag.png in the project navigator again and continue.

You’ll see that where flag.png is shown in the project navigator, there’s still no disclosure triangle to indicate that it’s a localized resource. That’s because we still have just one version of it, in en.lproj, just as BIDViewController.xib started out.

Make sure flag.png is still selected, and use the Localization section of the file inspector to add a new localization. This time when the popup list appears, you’ll see both English and French at the top of the list, since Xcode knows those are already represented in the project. Select French, and you’ll see that flag.png immediately acquires a disclosure icon. Expand that, and you’ll see two copies of the flag: one labeled English and one labeled French.

Switch back to the Finder and your project’s directory, and you’ll see this situation mirrored in the file system, with en.lproj and fr.lproj each containing a flag.png file. The one in fr.lproj is a copy of the original, which is obviously not the correct image. Since Xcode doesn’t let you edit image files, the easiest way to get the correct image into the localization project is to just copy that image into the project using the Finder.

Go to the 21 - LocalizeMe folder, open the Images folder, open the French folder, and use the flag.png file in that folder to replace the flag.png you’ll find in LocalizeMe/fr.lproj.

That’s it. You’re finished. Back in Xcode, click the image file flag.png (French) in the project navigator. You should see the French flag.

Now, try running the app again. We hope you’ll see something akin to the image shown in Figure 21–9. If not, do not despair. Chances are the US version of the flag image is being cached, either by the simulator or by the device, if you are running the app that way. We’ll go over a couple approaches you can try to get the correct image.

Figure 21–9. The flag image and application nib are both localized to French now.

If you are running in the simulator, first quit the app (but not the simulator). Click over to Xcode and stop the application. Return to the simulator and select iOS Simulator ![]() Reset Contents and Settings to reset the simulator, and then quit the simulator. Return to Xcode and select Product

Reset Contents and Settings to reset the simulator, and then quit the simulator. Return to Xcode and select Product ![]() Clean to force a complete rebuild. Now, run the app again. Once you rerun the app, you’ll need to reset the region and language to get the French flag to appear. If this still does not work, try doing the simulator reset, quit the simulator, do a Product

Clean to force a complete rebuild. Now, run the app again. Once you rerun the app, you’ll need to reset the region and language to get the French flag to appear. If this still does not work, try doing the simulator reset, quit the simulator, do a Product ![]() Clean, quit Xcode, and then start the whole thing again.

Clean, quit Xcode, and then start the whole thing again.

If you’re running on the device, your iPhone has probably cached the American flag from the last time you ran the application. You can remove the old application from your iPhone using the Organizer window in Xcode. Select Window ![]() Organizer to bring up the Organizer window. Under the Devices tab, you’ll see a column on the left showing all the iOS devices that Xcode knows about. The currently connected device has a green dot next to its name. Select the Applications item belonging to your devices, and you’ll see a list of all the applications you’ve compiled and installed on your own. Find LocalizeMe in the list, select it, and click the minus (−) button to remove the old version of that application and the caches associated with it. Now, select Project

Organizer to bring up the Organizer window. Under the Devices tab, you’ll see a column on the left showing all the iOS devices that Xcode knows about. The currently connected device has a green dot next to its name. Select the Applications item belonging to your devices, and you’ll see a list of all the applications you’ve compiled and installed on your own. Find LocalizeMe in the list, select it, and click the minus (−) button to remove the old version of that application and the caches associated with it. Now, select Project ![]() Clean. When that’s complete, build and run the application again. Once the application launches, you’ll need to reset the region, and then the language. The French flag should now come up in addition to the French words down the left side (see Figure 21–9).

Clean. When that’s complete, build and run the application again. Once the application launches, you’ll need to reset the region, and then the language. The French flag should now come up in addition to the French words down the left side (see Figure 21–9).

Generating and Localizing a Strings File

In Figure 21–9, notice that the words on the right side of the view are still in English. In order to translate those, we need to generate our base language strings file and then localize that. To accomplish this, we’ll need to leave the comfy confines of Xcode for a few minutes.

Launch Terminal.app, which is in /Applications/Utilities/. When the terminal window opens, type cd followed by a space. Don’t press return.

Now, go to the Finder, and drag the project folder 21 -LocalizeMe to the terminal window. As soon as you drop the folder onto the terminal window, the path to the project folder should appear on the command line. Now, press return. The cd command is Unix-speak for “change directory,” so what you’ve just done is steer your terminal session from its default directory over to your project directory.

Our next step is to run the program genstrings and tell it to find all the occurrences of NSLocalizedString in your .m files in the Classes folder. To do this, type the following command, and then press return:

genstrings ./LocalizeMe/*.m

When the command is finished executing (it just takes a second on a project this small), you’ll be returned to the command line. In the Finder, look in the project folder for a new file called Localizable.strings. Drag that to the LocalizeMe folder in Xcode’s project navigator, but when it prompts you, don’t click the Add button just yet. First uncheck the box that says Copy items into destination group’s folder (if needed), because the file is already in your project folder. Click Finish to import the file.

CAUTION: You can rerun genstrings at any time to re-create your base language file, but once you have localized your strings file into another language, it’s important that you don’t change the text used in any of the NSLocalizedString() macros. That base-language version of the string is used as a key to retrieve the translations, so if you change them, the translated version will no longer be found, and you will need to either update the localized strings file or have it retranslated.

Once the file is imported, single-click Localizable.strings, and take a look at it. It contains five entries, because we use NSLocalizableString five times with five distinct values. The values that we passed in as the second argument have become the comments for each of the strings.

The strings were generated in alphabetical order. In this case, since we’re dealing with numbers, alphabetical order is not the most intuitive way to present them, but in most cases, having them in alphabetical order will be helpful.

/* The number 5 */

"Five" = "Five";

/* The number 4 */

"Four" = "Four";

/* The number 1 */

"One" = "One";

/* The number 3 */

"Three" = "Three";

/* The number 2 */

"Two" = "Two";Let’s localize this sucker.

Make sure Localizable.strings is selected, and then repeat the same steps we’ve performed for the other localizations:

- Open the file inspector if it’s not already visible.

- In the Localizations section, click the + button once to create an English localization. This will likely unselect the file, but it will create the English localization.

- Reselect Localizable.strings. Then click the + button once again to make a French localization.

Back in the project navigator, select the French localization of the file. In the editor, make the following changes:

/* The number 5 */

"Five" = "Cinq";

/* The number 4 */

"Four" = "Quatre";

/* The number 1 */

"One" = "Un";

/* The number 3 */

"Three" = "Trois";

/* The number 2 */

"Two" = "Deux";

In real life (unless you’re multilingual), you would ordinarily send this file out to a translation service to translate the values to the right of the equal signs. In this simple example, armed with knowledge that came from years of watching Sesame Street, we can do the translation ourselves.

Now save, compile, and run the app. You should see the relevant numbers translated into French.

Localizing the App Display Name

We want to show you one final piece of localization that is commonly used: localizing the app name that’s visible on the home screen and elsewhere. Apple does this for several of the built-in apps, and you might want to do so as well.

The app name used for display is stored in your app’s Info.plist file, which, in our case, is actually named LocalizeMe-Info.plist. You’ll find it in the Supporting Files folder. Select this file for editing, and you’ll see that one of the items it contains, Bundle display name, is currently set to ${PRODUCT_NAME}.

In the syntax used by Info.plist files, anything starting with a dollar sign is subject to variable substitution. In this case, this means that when Xcode compiles the app, the value of this item will be replaced with the name of the product in this Xcode project, which is the name of the app itself. This is where we want to do some localization, replacing ${PRODUCT_NAME} with the localized name for each language. However, as it turns out, this doesn’t quite work out as simply as you might expect.

The Info.plist file is sort of a special case, and it isn’t meant to be localized. Instead, if you want to localize the content of Info.plist, you need to make localized versions of a file named InfoPlist.strings. Fortunately, that file is already included in every project Xcode creates, so all we need to do is localize it.

Look in the Supporting Files folder and find the InfoPlist.strings file. Use the file inspector’s Localizations section to create a French localization using the same steps you did for the previous localizations (it starts off with an English version located in the en.lproj folder).

Now, we want to add a line to define the display name for the app. In the LocalizeMe-Info.plist file, we were shown the display name associated with a dictionary key called Bundle display name, but that’s not the real key name! It’s merely an Xcode nicety, trying to give a more friendly and readable name. The real name is CFBundleDisplayName, which you can verify by selecting LocalizeMe-Info.plist, right-clicking anywhere in the view, and selecting Show Raw Keys/Values. This shows you the true names of the keys in use.

So, select the English localization of InfoPlist.strings, and add the following line:

CFBundleDisplayName = "Localize Me";

Now, select the French localization of the InfoPlist.strings file. Edit the file to give the app a proper French name:

CFBundleDisplayName = "Localisez Moi";

If you build and run the app in the simulator right now, you may not see the new name. iOS seems to cache this information when a new app is added, but doesn’t necessarily change it when an existing app is replaced by a new version—at least not when Xcode is doing the replacing. So, if you’re running the simulator in French but you don’t see the new name, don’t worry. Just delete the app from the simulator, go back to Xcode, and build and run the app again.

Now, our application is fully localized for the French language.

Auf Wiedersehen

If you want to maximize sales of your iOS application, localize it as much as possible. Fortunately, the iOS localization architecture makes easy work of supporting multiple languages, and even multiple dialects of the same language, within your application. As you saw in this chapter, nearly any type of file that you add to your application can be localized.

Even if you don’t plan on localizing your application, get in the habit of using NSLocalizedString instead of just using static strings in your code. With Xcode’s Code Sense feature, the difference in typing time is negligible, and should you ever want to translate your application, your life will be much, much easier.

At this point, our journey is nearly done. We’re almost to the end of our travels together. After the next chapter, we’ll be saying sayonara, au revoir, auf wiedersehen, avtío, arrivederci, hej då, and adiós. You now have a solid foundation you can use to build your own cool iOS applications. Stick around for the going-away party though, as we still have a few helpful bits of information for you.