TEAMWORK

It is the long history of humankind (and animal kind, too) that those who learned to collaborate and improvise most effectively have prevailed.1

—CHARLES DARWIN

This is a story about teamwork that involves two really different types of leaders, both of whom were devoted to high-performing teamwork: Navy SEAL instructors and professional baseball coaches. Between deployments, SEAL instructors train SEAL cadets. Professional baseball coaches have played the game at a high level and now coach minor and major league baseball players. In 2020, both teams came to the Cleveland Major League Baseball spring training in Goodyear, Arizona, to share insights on performing at a high level under conditions of extreme pressure.

The acronym SEAL stands for Sea, Air and Land, the three theaters of special forces operations. For example, SEALs might be tasked with the mission to control a perimeter around a building held by terrorists. SEALs give time for “friendlies,” or someone who is a supporter, to clear the building. Those who remain are assumed to have bad intent until proven otherwise. SEALs enter the building facing agonizing “shoot or don’t shoot” decisions. A 10-year-old boy might be tied to a suicide vest, or a wife might be held against her will. Don’t shoot, and SEALs die. Shoot, but there’s a victim with no gun, and you are brought up on charges and have to leave the country. A CNN story about killing an innocent person damages military strategy more than anything the enemy can inflict. On a personal level, a solider suffers a lifelong moral injury sentence for killing an innocent civilian.

Professional baseball players do not face life-or-death decisions, though they do share the SEALs’ mandate to perform under intense pressure. Baseball is a game of failure, and when a player screws up, their mistakes are seen by thousands of fans in the stands and millions on TV. The game of baseball demands that players get better by learning from, rather than fearing, failure.

The SEALs and coaches traded places to learn again what it felt like to be a beginner. For example, a SEAL sprinted with impressive closing speed to catch a fly ball; however, the closer he got to the ball, the clearer it became that he played like a beginner. In a batting cage, a SEAL swung violently, but again the probability of ball contact was low. Then, the coaches talked smack to the SEAL and then quickly diagnosed and corrected the flaws in his swing. Soon, he started hitting the ball.

Then, it was time to trade places. The SEALs taught the baseball coaches how to clear a room, including making split-second, friend-or-foe decisions. The SEALs cleared a room with precision and speed. Every movement was carefully choreographed. When it was the coaches’ turn, the coaches were slow and clumsy. They shot when they shouldn’t have, killing an imaginary child. They didn’t shoot when they should have, which simulated a coach getting killed. The SEALs talked smack to the coaches. They quickly corrected the flaws in the coaches’ footwork. While the coaches were not going to become honorary SEALs anytime soon, their speed increased and they better distinguished between people of goodwill and ill will.

So, what lessons on teamwork did each group learn from the other? Baseball coaches learned that the military has long held the view that bonding and trust are essential to performance. SEALs train by holding up logs or 300-pound boats to reveal who literally doesn’t pull their weight. The rest of us aren’t interested experiencing that kind of punishment. And we don’t need to be ultra-fit to know which of our teammates metaphorically carry their weight. We all have experienced hardship that on a good team cultivates the kind of trust necessary for sacrifice and selflessness. When teams achieve the “I have your back” culture, they perceive stress as a challenge instead of a threat.

SEALs don’t see themselves as super soldiers. They do see themselves as being part of super teams. SEALs never want to let their teammates down and never want to be average. It is not just about being tough, smart, and skilled. To be elite, you have to excel in helping your teammates. Each SEAL literally puts their life in the hands of their teammates, so that trust, not just military tactical skill, makes teams tough to beat.

The SEALs learned that the Cleveland baseball team won the most regular season games over a half dozen seasons, even though they had fewer resources than other teams. They carefully invested in areas, such as technology, that could efficiently improve player performance. For example, a small device attached to a bat calculated the hitter’s bat speed and launch angle. A small device inserted into the back of a player’s uniform tracked effort, heart rate, and where the player ran. But player performance depends on more than technology. A wise coach doesn’t talk baseball when they first meet a player. They read a player’s bio and ask, “Hey, I see that you grew up in a small town in Texas. What was it like to live there?”

In trading places, the SEALs and coaches learned about the “curse of knowledge.” What is that? Once we know something, we are not able to imagine not knowing it, which acts like a blind spot. More often than not, experts forget what it is like to be a beginner. The more we know, the harder it is to put ourselves in the shoes of those unfamiliar with our area of expertise.

Experts in special operations and baseball cannot unlearn what they know, and typically they don’t imagine what it is like to be a beginner. The SEALs were incredibly competent in clearing and taking control of a room. However, based on the curse of knowledge, some offered too much advice. But one SEAL instructor was particularly effective. Why? He was empathic toward beginners and economic in his language, and he offered a single cue to improve footwork. He could put himself in the shoes of the beginner, and he taught patiently.

It is interesting to peek into the worlds of special operations and professional baseball and see how they intersect on the common theme of developing high performance in teams, despite pressure and uncertainty. However, this is not a story about being a solider or an athlete. Few of us have the skill, never mind the interest to do either. It’s a story about developing high-performing teams.

Here’s the real challenge for all teams. Whether we know too much or know too little, the hard part is coming to grips with our shared plight to avoid looking stupid or inept, or to stand out against the team.

Imagine a team that does not expect perfect teammates. They trust each other because they know their teammates will get back up after they fall. Imagine teammates that understand that learning is best achieved by helping another person succeed, even above their own individual success. Imagine being part of a team like that. Now that would be an awesome place to work.

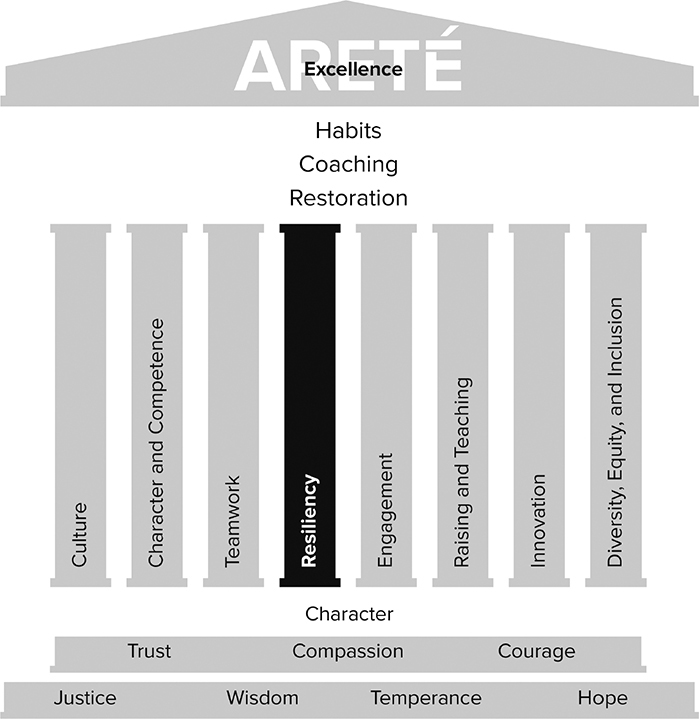

When we unpack the elements of high-performing teams, five common themes jump out as actions that just might make a place to work occasionally awesome (see also Figure 5.1):

1. Build relationships. Teams whose members enjoy strong relationships defined by virtue, even if not perfect, create the psychological safety necessary for learning under conditions of pressure and uncertainty. Trust and compassion are foundational to the work of the team.

2. Leverage strengths. Teams that perform well offset one teammate’s weaknesses with another member’s strengths. It is easier to build on a strength than it is to overcome a weakness.

3. Create clarity. Great teams ask: “What does good look like?” They start by getting clear about their goals and what success would look like.

4. Define purpose. Great teams are really clear about the purpose of their work together. They are clear about whom they serve.

5. Drive results. Great teams ask and are clear about the desired outcomes of their work. They recognize the differences between tangible outcomes, which may not always be in their control, and the intangible results, which usually regard the process of their teamwork and the culture that they do control. Again, when we get good at who we are, we get better at what we do.

Figure 5.1 Five Actions to Make the Workplace Awesome

These five steps are sequential, though they may not be linear. Let’s start with the first step: building relationships.

1. BUILD RELATIONSHIPS

When your team fears they will be ignored, humiliated, or blamed for making suggestions to improve or mitigate risk, they will underperform. Teammates need to feel safe and trust one another. Lack of trust is a major source of team dysfunction. Evidence that these ideas are generalizable comes from Brandeis University Professor Jody Gittell’s work on relationships and high performance.2 She initially studied the then high performer among airlines: Southwest Airlines. She identified three elements that composed the “secret sauce” of Southwest’s performance that differentiated the company from other airlines:

1. An environment that emphasized shared goals, shared knowledge, and mutual respect.

2. Robust communication techniques that made communication frequent, timely, and focused on problem solving.

3. Having an inventory of organizational practices that built relationships between managers and frontline employees. These included hiring and training for relationship excellence and using conflict to build relationships.3

Professor Gittell concluded that Southwest’s leaders “see these relationships—with their employees, among their employees, and with outside parties—as the foundation of their competitive advan-tage, through good times and bad. They see the quality of these relationships not as a success factor but as the most essential success factor.”

OK, you say. Works in the airline industry. Anywhere else? Does the power of relationships to achieve high performance extend beyond airlines? Yes! Professor Gittell went on to study the complex world of healthcare.

In a landmark study of surgical outcomes in nine hospitals around the United States, she framed the concept of relational coordination to summarize how coworkers work together. Relational coordination “comprises frequent, timely, accurate communication, as well as problem-solving, shared goals, shared knowledge, and mutual respect among health care providers.” No surprise: measures of relational coordination showed tight correlations with improved surgical outcomes in all hospitals. The more we value people and the better they work together, the better the outcomes of our work.

Let’s consider another example of relational coordination in one of the most complicated places in a hospital: the intensive care unit (ICU). Good outcomes there are literally life or death, and they depend critically on the fluid interaction of lots of healthcare providers. The ICU team in the Shock Trauma ICU (STRICU) of the Latter Day Saints Hospital in Utah cares for the sickest of the sick—patients with medical illnesses that threaten life, like overwhelming infection and literally body-crushing trauma. A STRICU team consists of caregivers such as physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, technicians, nutritionists, pharmacists, ethicists, and unit administrators. All are committed to improving patient outcomes by embracing five principles to enhance teamwork. These five principles were informed by Nobel Laureate behavioral economists’ research about optimizing outcomes, and they closely resemble the dimensions of relational coordination:

1. Develop a shared purpose.

2. Create an open and safe environment (that is, psychologically safe), and encourage diverse views.

3. Include all those who share the common purpose.

4. Learn how to negotiate agreement, and teach these skills to all stakeholders.

5. Insist on fairness and equity in applying all norms and rules.4

The STRICU team leadership—the medical director and the nurse manager—made a commitment to model these behaviors in all their interactions. They codeveloped a statement—that is, a credo—of their shared purpose to improve the outcomes of the patients for whom they cared, and they shared this credo with all their colleagues. The medical director and nurse manager committed to publicly demonstrate their cooperation. When they developed care protocols that guided many of the processes in the STRICU, for example, how to treat elevated blood sugar values or how to liberate patients from mechanical ventilation, they did so together, and then they invited all members of the STRICU community to offer their candid input about those protocols before they were implemented. Recognizing that ICUs sometimes have an implicit hierarchy in which caregivers who are not physicians can sometimes feel intimidated by the physicians’ presence, the doctors in the STRICU would reach out individually to seek all STRICU stakeholders’ (for example, nurses’ and respiratory therapists’) views.

Negotiation training was developed and made available to all members of the STRICU team. They were all encouraged to be hard on problems and soft on people and, whenever possible, to use hard metrics and data to guide decisions. Finally, they committed to apply rules equitably to all STRICU stakeholders. For example, when deadlines for comments on new protocols were announced, late input was dismissed from physicians and other caregivers alike. Conversely, input from all was actively invited during the announced comment periods on the protocols.

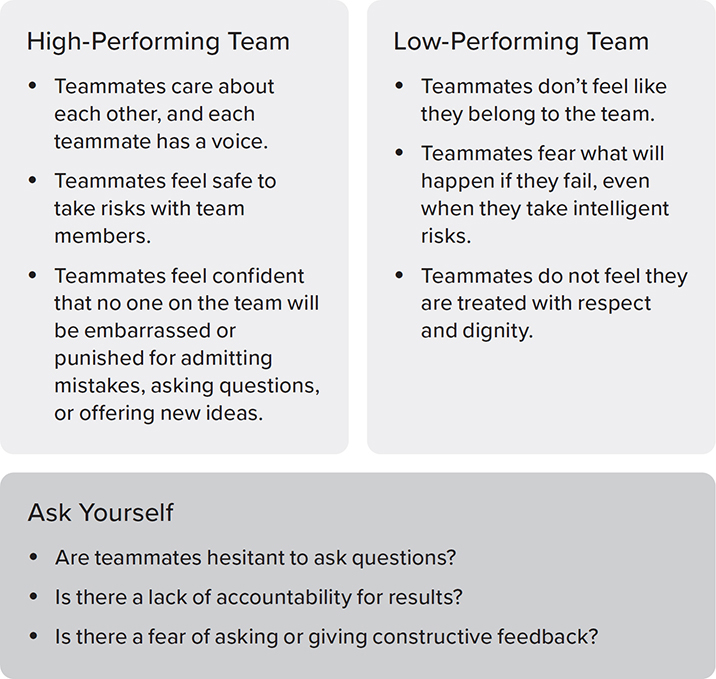

The results of this four-year effort to improve patient outcomes in the STRICU were impressive. Practices in sedating patients and using powerful paralytic drugs for various STRICU procedures improved. Control of important blood chemistry values like potassium and blood sugar levels improved. And the use of antibiotics, which when overused can have an adverse impact by creating resistance of the infecting microorganisms to these agents, was enhanced. And, as a bonus, all of these clinical improvements were accompanied by a 30 percent decrease in STRICU costs of care and a 19 percent decrease in the overall hospital cost of care for these patients. Clearly, collaborative teamwork matters. Figure 5.2 features a checklist and an assessment tool that can help strengthen collaboration. Check one area that would most strengthen performance for your team.

Figure 5.2 A Checklist and Assessment Tool That Can Help Strengthen Collaboration

2. LEVERAGE STRENGTHS

Teams learn faster when they are strengths-based because a focus on weaknesses—not strengths—diminishes performance. Gallup compared 50,000 teams in 192 organizations that ranged in performance from high to low. Almost none of the variance in performance was about pay and career opportunities. Instead, the statement that explained most of the variance in performance was, “At work, I have the opportunity to do what I do best every day.” Teammates who reported “strongly agree” on this item, were 44 percent more likely to earn a high customer satisfaction score, 50 percent more likely to be retained, and 38 percent more likely to be productive.5

Performance evaluation systems can undermine strengths-spotting when leaders deliver some version of a “crap sandwich”: say something nice, point out “areas for growth,” and then say something nice. Deloitte offers a subtle, though powerful, “crap sandwich” alternative. Don’t ask leaders what they think about a teammate’s skills. Ask what they would do to help their teammate.6

While we stink at rating others, we are highly consistent in creating actions to support a teammate’s growth and learning. Of course, evaluations on compensation still need to be made. Importantly, we should separate in time the extrinsic part of evaluation (pay) from the intrinsic part of development (learning and growth). When we mix pay and development, all we hear is pay as a proxy for whether we are valued.

Traditional performance assessment involves infrequent judgment, which means evaluation is often limited to a once-a-year event. As an alternative, imagine a system and a culture that relied on the science of high performance by focusing on teamwork, resilience, and regular coaching. Deep learning is about recognizing strengths and then reinforcing and refining strengths. A leader could say to an impressive teammate, “When I observe how you help others, this is what you made me think about (recognize). When members of the team were struggling to get back up after getting knocked down, you helped the team focus on what they needed to learn in order to get better.”

Good coaches ask questions rather than offer answers. For example, before you take on the problem of people feeling discouraged, ask what’s working now. When you have had a problem similar to this, what worked? What do you already know you need to do? The emphasis is on what and how questions rather than why because asking why implies judgment. What and how are the questions of a skilled coach.7 All this is to say, let’s just see if we can do a better job leveraging strengths and managing weaknesses.

How Well Does Your Team Leverage Strengths?

But let’s face it. As we saw, humans are deficit-based animals. We see the potholes in the road instead of the beautiful horizon. The issue is not, “What is broken and how do I fix it?”—a distinctly deficit-based approach—but rather, “Who are we when we are at our best?” and “What skills do we have that, when developed yet further, can improve our work?” Organizational thinkers call this an appreciative approach. Words create worlds, and the way we frame the issue informs the answers we generate. And appreciative framing informs better answers than deficit-based thinking.

Consider another context: marriage counseling. One approach to marriage counseling involves partners describing how each person drives the other one nuts. The remedy is for each partner to correct their annoying behavior—usually with disappointing results. In contrast, research reveals that marriages destined for success involve two people overlooking each other’s flaws. When a spouse messes up, their partner grants them the benefit of the doubt. When we overreact to negative events, we lose perspective and make matters worse.

Fear is the engine of negativity and becomes a prediction of what will happen, even when that outcome is unlikely. About 85 percent of what we worry about never happens, and the remaining 15 percent often wasn’t as bad as we feared. When we acquire a more precise account of what is actually happening, we can read our fears accurately and gain a bit of wisdom and perspective. So, when your fear story kicks in, consider asking three questions to reduce the power of negativity:

![]() What is the worst that could happen?

What is the worst that could happen?

![]() What is the likelihood that the worst will happen?

What is the likelihood that the worst will happen?

![]() If the worst happened, could we handle it?

If the worst happened, could we handle it?

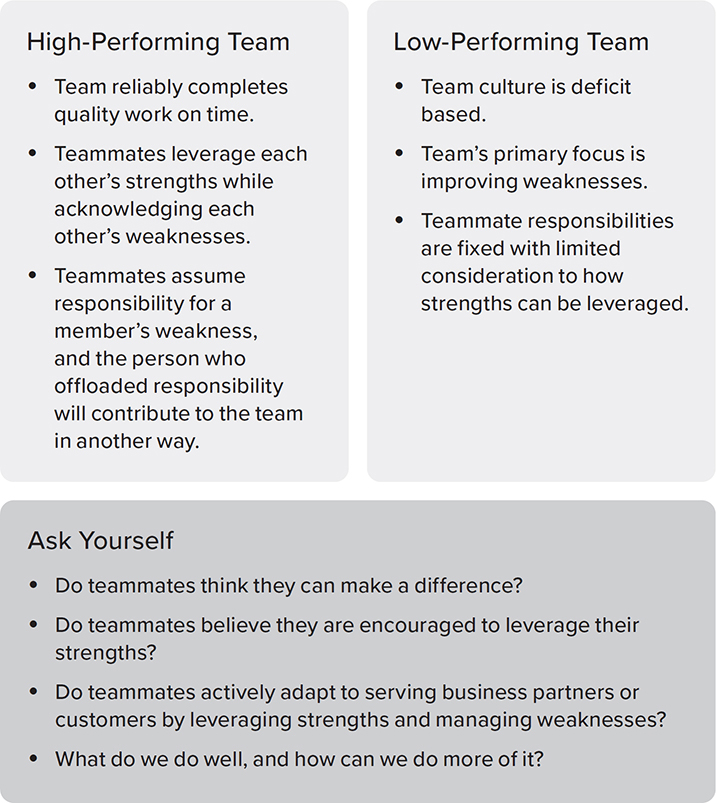

If we increase the amount of time that each person uses their strengths, then performance increases. And we will also increase personal satisfaction. Figure 5.3 features a checklist and an assessment tool that can help strengthen the ability of teams to leverage their strengths. Check one area that would most strengthen performance for your team.

Figure 5.3 A Checklist and Assessment Tool That Can Help the Ability of Teams to Leverage Their Strengths

3. CREATE CLARITY

The third step asks the question, “What does good look like?” The answer helps teams develop shared clarity and structure in the work. A shared vision clarifies what is expected. Otherwise, good people get discouraged working at cross-purposes.

Chartering at the beginning of a team’s work is an effective way to achieve clarity and alignment. In chartering, every member of the team is invited by the leader to weigh in on the question, “If our work together is successful, what do we do?” Answering this question at the front end of the team’s work enables people to identify, discuss, and resolve differences. Do this work at the front end, to avoid misalignment at the back end. Part of chartering is clarifying the roles and responsibilities of each team member. Two questions and two statements can help here:

![]() Ask teammates and partners, what do you expect of me?

Ask teammates and partners, what do you expect of me?

![]() Ask teammates and partners, what don’t you expect of me?

Ask teammates and partners, what don’t you expect of me?

![]() Tell teammates and partners what you expect of them.

Tell teammates and partners what you expect of them.

![]() Tell teammates and partners what you don’t expect of them.

Tell teammates and partners what you don’t expect of them.

These simple questions can go a long way to aligning expectations and efforts. In the following section is a checklist to assess whether your team has clarity.

Is Clarity a Strength of Your Team?

In addition to being clear on goals, roles, and responsibilities, how people treat each other predicts performance more than who is on the team. Specific ground rules of team behaviors are important to high-performing teams. These behaviors include the following:

![]() Listening by summarizing what others said—also referred to as active listening

Listening by summarizing what others said—also referred to as active listening

![]() Admitting what we don’t know

Admitting what we don’t know

![]() Making sure everyone speaks

Making sure everyone speaks

![]() Avoiding interrupting teammates

Avoiding interrupting teammates

![]() Encouraging people to express frustrations

Encouraging people to express frustrations

![]() Encouraging teammates without judgment

Encouraging teammates without judgment

![]() Calling out conflicts and resolving conflicts openly8

Calling out conflicts and resolving conflicts openly8

An especially important behavior in a high-performing team that is essential to creating clarity is ensuring that everyone has a voice. Leaders must invite—indeed insist on—full participation. In turn, every teammate is obligated to make the team stronger. Before the meeting ends, ask each person, “What are your thoughts?” “What do you see that we are missing?” “What do you know that I should know?”

Figure 5.4 features a checklist and an assessment tool that can help strengthen clarity for teams. Check one area that would most strengthen performance for your team.

Figure 5.4 A Checklist and Assessment Tool That Can Help Strengthen Clarity for Teams

4. DEFINE PURPOSE

The fourth step in creating high-performing teams is defining purpose. When we can align our team around how we treat each other and having a shared purpose, we are on a mission. While purpose has a powerful impact on performance, the idea is abstract. We can be more concrete about purpose by considering how we treat others and whom we serve.

Let’s start with how we treat others. People are not changed by programs. We know people are changed by relationships. Virtue is the most pro-social relationship practice of all. So, our aspiration, not always our reality, is to treat each other by practicing virtue.

The second question asks, “Whom do we serve?” We define our purpose based on value sought by the people we serve, not based on what we think others need. The point of purpose isn’t to pat ourselves on the back but to actually help others. How do we know what would help someone? We don’t guess. We ask them. If we get this right, then we are on a purpose-driven mission. When our purpose is clear, inevitable problems become speed bumps rather than impenetrable walls. In the following section, consider the checklist of attributes of purpose-driven teams.

To What Degree Does Your Team Have a Shared Purpose?

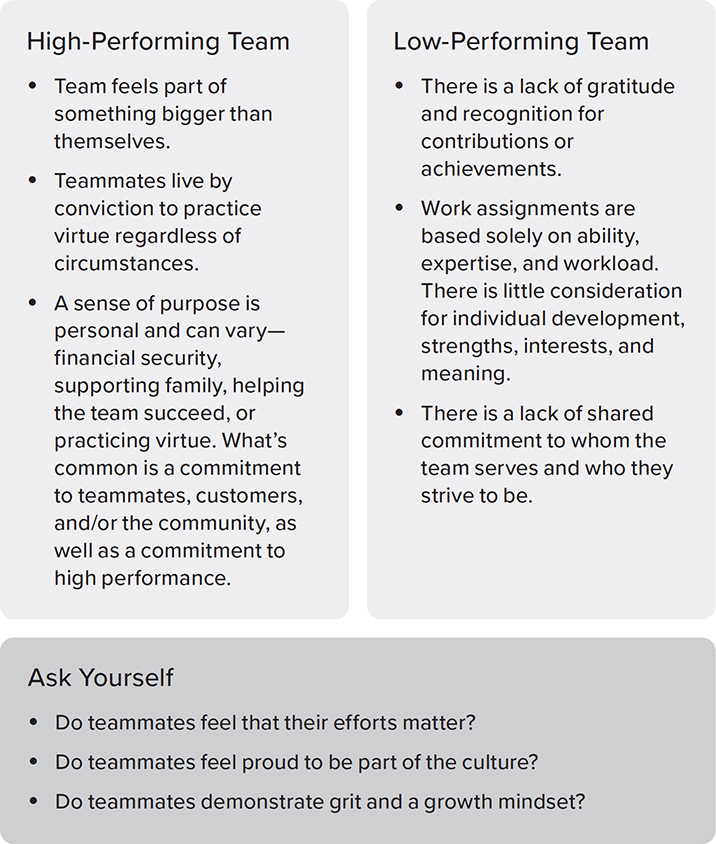

Figure 5.5 features a checklist and an assessment tool that can help your team members determine the strength of their shared purpose. Check one area that would most strengthen performance for your team.

Figure 5.5 A Checklist and Assessment Tool That Can Help Strengthen a Team’s Sense of Shared Purpose

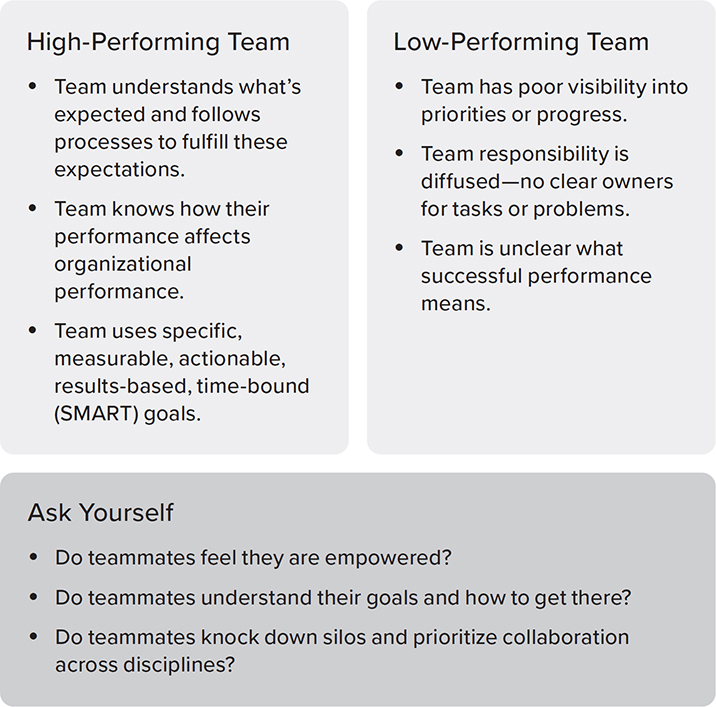

5. DRIVE RESULTS

The fifth step in creating a high-performing team is to drive results. Effort is laudable, but results are what matters. It’s one thing if a team misses its plan by a little. It is quite another when a team misses its plan by a lot. The consequences of a big miss can limit an organization’s ability to serve others and limit teammates’ ability to grow, or worse, it can cost hardworking people their jobs.

We all want to work on a team that makes a positive impact. Impact can be defined by both tangible and intangible results. Tangible results include objective metrics, such as financial performance. Intangible results include ideals that are subjective but not as easy to measure, such as whether a team feels their work stands for something that matters.

What Is the Impact of Results on Your Team’s Performance?

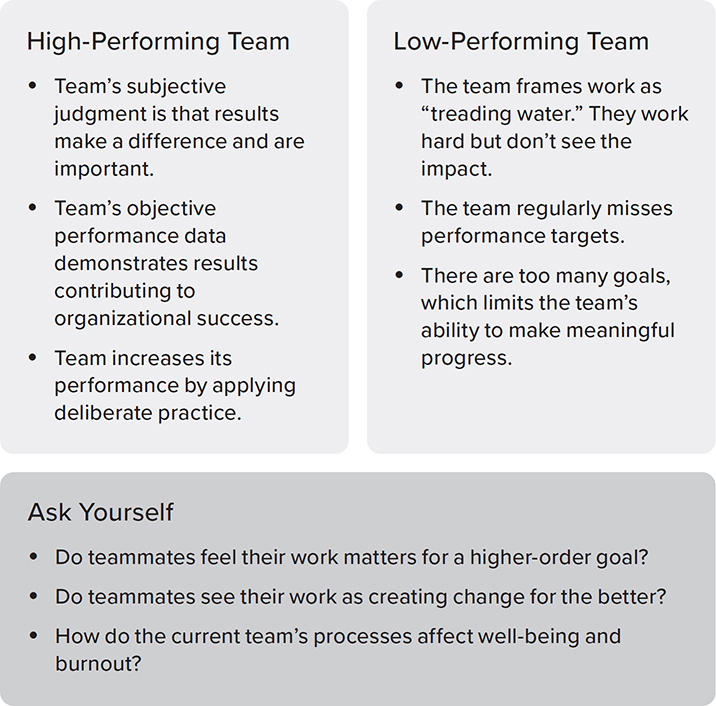

Figure 5.6 features a checklist and an assessment tool that can help your team determine the impact of results on their performance. Check one area that would most strengthen performance for your team.

Figure 5.6 A Checklist and Assessment Tool That Can Help a Team Determine the Impact of Results

Because results are so important, a growth mindset is a healthy way to think about effort and results. Carol Dweck, in her work on the growth mindset, shared these three strategies:

1. Your brain is like a muscle—exercise it. When we do something that is hard and important, something we haven’t done before, our brain fires up new neurons. When we keep doing the same thing no matter how hard we work, the result is no new neurons and no new smarts. Our brain doesn’t care if we succeeded or failed. It just knows when we are trying to learn something new, and it responds by connecting new neurons to develop new abilities.

2. Adopt a growth mindset. Understand the difference between a growth mindset that sees talent as something that is developed versus a fixed mindset that is limiting because it sees talent as something we either have or we don’t.

3. See “not yet” as opportunity. If we fell short of our targeted results, we need to learn and consider what capabilities we need to develop and with whom we should form a partnership in order to succeed. In other words, we are not yet where we want to be. “What now?” Not, “Why me?”9

Let’s go the other way. You delivered results, though team satisfaction is in the dumpster. While the tangible financial results are impressive, intangible results feel empty. This isn’t just fluffy philosophy. Getting results that don’t feel meaningful certainly isn’t sustainable. Peter Drucker viewed profits like breathing: necessary for life, but not a reason to live.

Consider if intangibles can be strengthened, such as trust and care among the team. Perhaps there is value in doubling down on teammates’ strengths or improving clarity. Ultimately, the issue is getting clear about a team’s purpose:

1. How do we strive to treat each other with dignity and respect?

2. Practice virtue, even if imperfectly.

3. Whom do we serve?

4. Define the people we serve, their pain points, and their alternatives.

5. Why is our value superior?

Perhaps teams can learn from the Navy SEALs’ training about purpose. Cadets are told to put away gear in the following order: team gear first, buddy gear second, self-gear third. After cadets receive this instruction, they are tied together to swim the cold water of Coronado Bay in San Diego until they are exhausted. They return to shore so physically spent that they are unable to think straight. Inevitably, the cadets take care of self-gear first, then buddy gear, then team gear. Loads of pushups in the sand help remind cadets of the original priority. Good luck asking a colleague to drop and give you 50 pushups. But it is within our reach to consider our teammates’ and buddies’ concerns before our own.10

PLAYBOOKS TO STRENGTHEN TEAM PERFORMANCE

With the goal to increase team flourishing in mind, we offer a three-tiered performance sandwich. Relationships are the foundational bun, which can be strengthened by a team user manual. Psychological safety is the meat, which is a sophisticated task that includes assessment, understanding what promotes and inhibits team performance, and then practice. An after action review (AAR) tops off the sandwich, which is a concrete way to practice team learning. So, relationships first, psychological safety second, and after action review third.

Team User Manual

Since trust is efficient, how can trust be earned quicker and deeper? Regrettably, the worst way is the most common way: people just get to work. We assume that everyone wants to work the way we do though this is rarely the case. Let’s call this teamwork by chance. Big surprise, teammates who don’t know how to get the best out of each other underperform. Let’s call the alternative approach teamwork by design. We assume that people differ significantly in how they best function on a team and a team user manual leverages differences:

Step 1. Create a team user manual: Teammates write brief answers to a series of questions.

Step 2. Members share their teammates’ answers with the larger team.

Step 3. The team creates a team user manual composed of one-page summaries of each teammate’s answers to who they are, the best way to interact with them, and their motivations and strengths.

Now, team members have the insights they need for individual teammates to perform at their best.

Here are questions that can be used to create a team user manual:

Who You Are

1. What should people know about you to get your best effort?

2. What drives you nuts?

3. How can people earn a gold star with you?

Best Way to Interact with You

1. What are the best ways and worst ways to communicate with you?

2. What are the best ways to give you hard news or critical feedback?

3. What are three things that help you best respond to pressure and uncertainty?

Your Motivations and Strengths

1. At your funeral, which virtues do you want people to say were your strengths?

2. Name three to five of your greatest competencies.

3. What are your best hopes and greatest concerns?

4. Describe when you leveraged your character and competency strengths to serve others.11

You can think of a team user manual as an anti-drama tool. It’s about intentionally getting to know your teammates at a much deeper level rather than slamming a group together and telling them to get to work. It creates more predictability and accelerates trust. Team performance is enhanced when turmoil is reduced.

Psychological Safety

When Harvard Business School Professor Amy Edmondson originally studied high-performing teams, she wasn’t looking for “psychological safety.” She was looking for determinants of high performance. What she found, though, was that psychological safety was a necessary condition for high performance.12

When people fear being humiliated, blamed, or ignored for bringing their ideas forward, they will shut down and disengage. Their teams or organizations will then underperform. Think about the absence of psychological safety as a giant brake on performance. Until you release the brake of fear, hitting the performance accelerator won’t help. It is that important.

Psychological safety isn’t a “soft phrase” because the point isn’t comfort. It’s candor. The goal isn’t psychological safety. The goal is motivation and accountability for results. The method doesn’t need to be tender and hypersensitive. Teams can learn to be tough, not rough.

What psychological safety does involve is getting the order right: relationships first and performance second. If trust and care are limited or missing in action, the candor needed to increase team performance will be missing. Constructive advice is best offered from a position of care and concern for our colleagues to do their best work. Think about it. You can offer advice to criticize—a “gotcha” moment—or you can offer advice to express authentic concern and compassion for your colleagues and their performance. Some of the best teammate relationships are so candid that people regularly bust on each other. Candor reigns when people have full confidence that their teammates have their back.

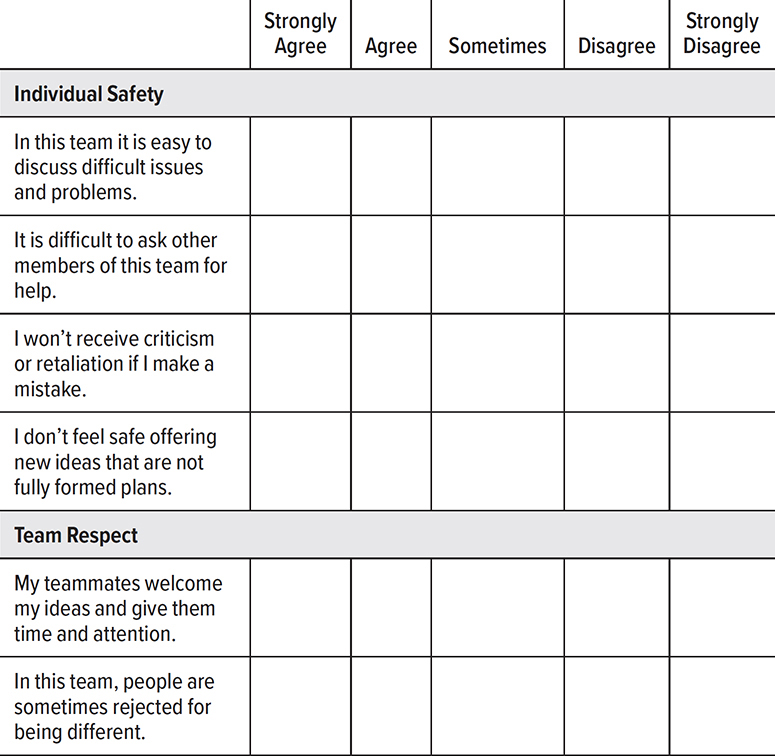

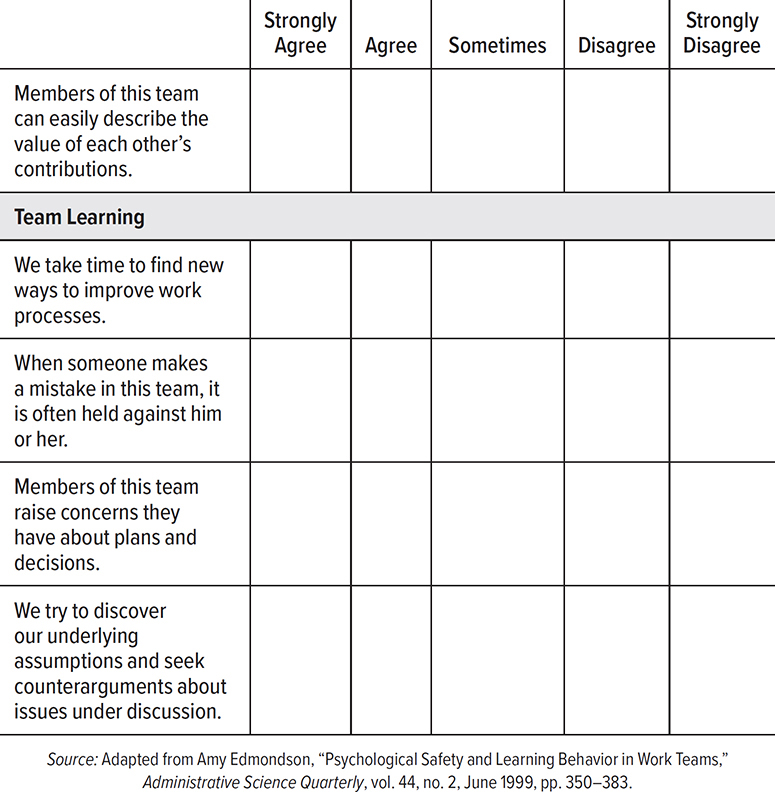

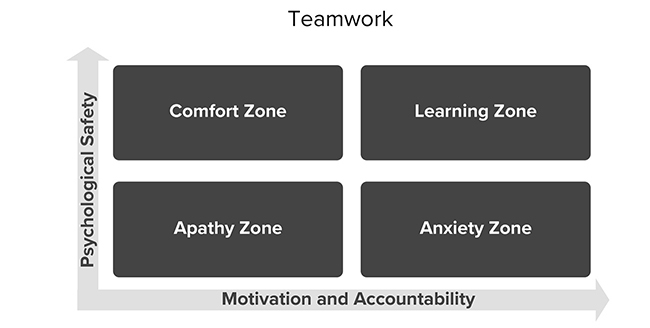

To achieve psychological safety, start with a team self-assessment. How psychologically safe is our work together? The assessment in Table 5.1 helps teams consider which of the four quadrants shown in Figure 5.7 best describes their team.

Table 5.1 Assessment of a Team’s Psychological Safety

Figure 5.7 The Four Quadrants of Psychological Safety

The comfort zone reflects a team with high psychological safety and low motivation and accountability for results. People enjoy lattes in the morning and each other’s company, but they are not getting much done.

The apathy zone is defined by low psychological safety and motivation and accountability for results. No lattes in the morning, and we don’t like each other either. Unemployment for all will probably come next.

The anxiety zone is the most common team experience defined by low psychological safety and high motivation and accountability for results. People want to deliver results, though they fear being humiliated, blamed, or ignored. This isn’t just about hurt feelings. This is about performance. When anxiety goes up, performance goes down.

Ideally, teams are in the learning zone, defined by high psychological safety and high motivation and accountability for results. These are the highest-performing teams.

Lock in on three behaviors that destroy psychological safety—humiliate, blame, and ignore. And three behaviors that create psychological safety—vulnerability, questioning, and learning. Start with vulnerability. We don’t trust arrogant leaders. We trust leaders who acknowledge their fallibility. When leaders “tell one on themselves,” for example, describe a time when they failed, we can all relate to that. All of us have screwed up. When the air of “do no wrong” is dismantled, then humility becomes contagious and binds people together.

Next, strong teams ask questions such as the following: “Do we provide the level of service we are capable of providing?” “Are we certain that we understand what our partners and customers need?” “What skills do we lack?” When questions like those are being asked, team learning can be kicked up a notch by using an after action review (AAR). This tool will be most impactful when relationships have been established with a team user manual and when some degree of psychological safety has been achieved.

After Action Review

Anyone interested in high-performing teams can quickly get behind the reality that the team that learns the fastest wins. The challenge is how to do this. Think of an after action review (AAR) as a concrete way for teams to increase the speed of team learning. Rather than presume that team learning will somehow just happen, an AAR assumes that team learning has to be intentional. Here are the basic steps for an AAR:

Purpose

![]() Repaint an accurate picture of what happened. This isn’t as easy as it might appear because people view the same experience differently based on their perspective.

Repaint an accurate picture of what happened. This isn’t as easy as it might appear because people view the same experience differently based on their perspective.

Foundational AAR Questions Include These

![]() What was expected to happen?

What was expected to happen?

![]() What actually occurred?

What actually occurred?

![]() What went well and why?

What went well and why?

![]() What can be improved and how?

What can be improved and how?

How Should the AAR Be Facilitated?

![]() Everyone on the team participates.

Everyone on the team participates.

![]() In fact, one key objective is that everyone on the team speaks. Trust has been established when everyone feels obligated to strengthen the team.

In fact, one key objective is that everyone on the team speaks. Trust has been established when everyone feels obligated to strengthen the team.

![]() An AAR aligns with psychological safety because the goal is candor, not comfort.

An AAR aligns with psychological safety because the goal is candor, not comfort.

![]() The team that struggles the most learns the most. An effective AAR pushes people beyond their comfort zone while being respectful.

The team that struggles the most learns the most. An effective AAR pushes people beyond their comfort zone while being respectful.

![]() Someone other than the senior leader facilitates the discussion. The AAR is an effective leadership development experience. Senior leaders can guide less experienced leaders to plan and facilitate an AAR.

Someone other than the senior leader facilitates the discussion. The AAR is an effective leadership development experience. Senior leaders can guide less experienced leaders to plan and facilitate an AAR.

![]() Brief and frequent is better than long and infrequent.

Brief and frequent is better than long and infrequent.

![]() The length of the AAR can be 15 minutes. The goal is to make the AAR a habit, and that won’t happen if it’s a burden.

The length of the AAR can be 15 minutes. The goal is to make the AAR a habit, and that won’t happen if it’s a burden.

PUTTING THE THREE-TIERED TEAM PERFORMANCE SANDWICH TOGETHER

The team user manual is trust by design rather than trust by chance. Psychological safety comes next, though this is exceedingly rare for reasons that take us back to preferring comfort over discomfort. It is far easier to hold back ideas, avoid asking questions, and view a disagreement with the boss as a career-limiting move. Even the term safety can be misunderstood. No one is completely safe. Perhaps the word security defined as the absence of deliberate harm is a more realistic standard, and even this definition doesn’t come with a 100 percent warranty.

Creating a psychologically safe culture is a sophisticated task. The first step is getting clear that the goal is performance, not psychological safety. The second step is getting clear that the goal is candor, not comfort. The third step is understanding that vulnerability, questioning, and learning need to be practiced.

One way to practice psychological safety is to reflect on an important project that has not made progress.13 Choose an important project that cuts across silos, so that no one person or function can solve the challenge. In a hospital setting, this might include access to care, which is a perennial challenge for all healthcare institutions. The physicians, nurses, and scheduling staff will likely be the first to see that patients can’t make timely appointments. In a psychologically safe culture, vulnerability, questioning, and learning kick into gear. Those who are seeing the problem will speak up to executive leadership. The executive team will ask questions to assess the scale and scope of the access issue. The executive team will assign a group of leaders to define the skills, teamwork, and processes needed to increase access to care.

When the project has seen some progress, learning is accelerated by conducting an after action review that involves a team reflecting on four questions:

1. What did we want to happen?

2. What actually did happen?

3. What did we do well?

4. Where can we do better?

It is hard to get an AAR to work as designed if trusting and caring relationships are missing in action. This is where a team user manual can make a valuable contribution. In addition, our brain learns better when we are psychologically safe. We can’t take trust or psychological safety for granted when people who don’t normally work together are tasked to solve a challenge, such as access to care in a hospital, that cuts across an organization. This is the kind of issue that will be viewed differently by clinical staff, administrative support, and executive leaders. Gaining insights from diverse perspectives to knock down organizational silos requires that vulnerability, questioning, and learning are not left to chance. They depend on intentional practice.