RAISING AND TEACHING BETTER HUMANS, BY JULIE REA

We must remember that intelligence is not enough. Intelligence plus character—that is the goal of true education.1

—MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR.

For over two decades, we have delivered seminars on the virtues to leaders. Frequently, after discussing and implementing practices to facilitate better performance in the workplace through the application of the virtues, leaders have asked whether these practices translate to home and family. They perceive the need to help their children develop as positive contributors to the family, their schools, and their communities, and they are curious how to use what they have learned at work in the family setting. Furthermore, the under-pinnings of a successful society and successful organizations are the people in them, all of whom grew up under the influence of teachers, parents, and friends.

Thus, beyond leaders’ inquiries about the impact of virtues on their homelife, the business case for practicing the virtues at home and in school is that the practice makes young people better, and better young people perpetuate high performance in their work and for society. Furthering the business case for helping people practice virtue with their families, remember that what occurs at home invariably makes its way back to work.

Another rationale for including a discussion of practicing virtue in families and in school in a book about high performance in organizations and society is that leaders know that the purpose of practicing virtue is to make an investment in their professional and personal growth, which includes supporting how they want to parent. Again, the method matters—pull, not push. Share the research and tools, and grant people freedom to apply what they learn at work and home. What follows are some suggestions for helping caregivers create a culture that supports children in developing into their best selves.

“Research suggests that almost all parents say they are deeply invested in raising caring, ethical children, and most parents see these moral qualities as more important than achievement.”2 Data from the teacher survey conducted by the Making Caring Common Project of the Harvard Graduate School of Education suggests that most teachers also view preparing youth to be caring as more important than their achievement.”3 Children, however, hear differently. What they hear the adults in their life saying is that achievement and happiness are more important than being a caring community member.

What is going wrong? How did our children hear, “You must be at the top of the class and be the best [musician/athlete/artist],” when we thought we were saying, “You must be kind and caring”?

Adam Grant and Alison Sweet Grant wrote in The Atlantic, “Kids learn what’s important to adults not by listening to what we say, but by noticing what gets our attention. And in many developed societies, parents now pay more attention to individual achievement and happiness than anything else. However much we praise kindness and caring, we’re not actually showing our kids that we value character.”4

Ironically, the more attention we pay to individual achievement and happiness, the more anxious our children become. Psychologist and author Madeline Levine notes, “As it stands, we are not preparing our children (or ourselves) very well for confronting an unpredictable, rapidly changing future. Just the opposite: in our efforts to protect our children from experiencing distress, we are unintentionally setting up the circumstances that nurture distress today and will surely exacerbate it tomorrow.”5

These tendencies toward anxiety persist into adulthood. As a tutor for adults pursuing a General Education Development Test (GED), I hear students apologize again and again for making mistakes or rationalize why they made an error in pronunciation or computation. Sometimes they cry; sometimes they quit in frustration. Their previous schooling experiences have taught them that the goal is not the journey to understanding. The goal is the correct answer, the first time, without hesitation. Such an outlook impedes progress greatly, as tutors must take time repeatedly to reassure the students that they are learning, that mistakes are part of the process, and the length of time it takes to understand a topic is not a mark of intelligence. When schools and parents value achievement over character, the anxiety produced in school becomes a fearsome barrier.

We want our children to be kind and caring people who make their communities better places to live and grow. We want our children to be prepared to live confidently and grow in an uncertain future. We want them to be resilient, able to withstand, and even grow, in the face of failure, setbacks, and disappointments. Our goals as parents resemble the goals for organizational leaders, who wish to build climates in which their work colleagues have resilience and do the right thing when nobody is watching. How do we accomplish this?

CHANGING THE MESSAGE

If we want to change what our children hear, we need to change our message and how we present it. In Self-Theories, Carol Dweck presents her research on the development of mindsets, an individual’s assessment of the malleability of intelligence. According to Dweck, based on our experiences, we develop an idea that either we can change our intelligence or we can’t. We believe that our efforts make a difference in what we can learn or achieve, or we believe that we are stuck with what we were given at conception. Dweck calls the belief that we can control our intelligence a growth mindset. In contrast, the belief that, regardless of effort, our intelligence is limited is a fixed mindset.6

At first glance, it is surprising to learn that some students with the highest grades have a fixed mindset. You might assume that these high achievers would have ample support for believing that hard work would generate results. Yet, in K–12 education, high achievers are frequently the ones for whom school has come easily. They have the self-control, fine motor skills, and inclinations to literacy and numeracy to make the routine tasks of school effortless. They not only tolerate but frequently welcome the repetition of content presentation followed by worksheet completion. They have been praised for getting right answers and getting them quickly. They know the game and excel at it.

Ask these same high achievers to tackle open-ended projects or complex questions common in the workplace and they may freeze. Because they have been rewarded for knowing the right answer, it stands to reason that not knowing the right answer immediately calls into question their intelligence. Maybe they are not as smart as everyone, including themselves, thought. Maybe they should retreat to the work they already know how to do. Continuing to put in effort, trying a new solution, or looking for help means that they have failed.

On the other hand, students with growth mindsets attack open-ended, complex, challenging tasks with relish. Not knowing the answers right away is an opportunity to apply new thinking or new strategies, to learn something new. They see these tasks as challenges. Rather than the defeatist self-talk of the fixed mindset students, the growth mindset students use encouraging self-talk, reminding themselves of what they know or motivating themselves to persist.

Dweck reports on research documenting ways to help students change the self-defeating narratives that hinder success on challenging tasks. In one study, students with a fixed mindset were given attribution retraining. That is, they were taught to assign an explanation for failure to not offering enough effort, rather than assigning it to not having enough intelligence. By reframing the reason for failure, these students improved in task-persistence (asking for help appropriately) and confidence.

Even more importantly, Dweck and fellow researchers demonstrated that when children are given the opportunity to correct errors with the instruction “to think of another way to do it,” they developed a mastery-oriented response to failure. They were more able to develop solutions to the problem; they expressed more positive attitudes about their experiences; and they believed more in the inherent goodness of people.

This repeated exposure to opportunities to learn from so-called failure is supported by experience from the Harvard Center for the Developing Child. In a report entitled 8 Things to Remember About Child Development, the center noted, “It is the reliable presence of at least one supportive relationship and multiple opportunities for developing effective coping skills that are the essential building blocks for strengthening the capacity to do well in the face of significant adversity.”7

So, What Do We Do to Help Children Develop a Growth Mindset?

Remember to ask your child if there is another way to do whatever they are trying to do.

As hard as it is to do, let your child fail. Then encourage them to figure out what to do next. If needed, offer suggestions to get them started. If an apology, atonement, or repair is in order, let them know you expect that will happen and will follow up until it is done.

Make sure to let your children know that we all fail, it is OK to fail, and that what is important is what we do next.

Model and encourage a not-yet attitude: I haven’t been successful yet, but with persistence, I can be.

Discuss examples of your own failures and what steps you took to atone for and repair your mistakes.

Point out examples of failures that turned out to be happy surprises—better than the original expectation had you (or someone else) not failed.

Consider using the items on the 4Gs scorecard (Chapter 4) as a series of question prompts to help you and your child focus on what is most important. For example: Did I practice compassion today? Did I get back up and try harder after a failure? Did I help others succeed? Did I deal with frustration positively?

RECOGNIZE THE PATTERNS

Teaching Algebra 1 to high school students who believe that math is unrelated to their life and adds nothing to their functioning as humans in the real world can be challenging. While coteaching math to a group of reluctant math learners, I heard many complaints of the “Why do we have to learn this?” and “When will I ever use this?” variety, even though my colleague and I spent hours creating engaging lessons targeted directly at these very questions.

One day, a student named Robert began his usual round of moaning about the math task of the day, and I started to say something motivational, such as, “Please stop talking and get to work,” when my incredibly talented coteacher said, “Oh, Robert, that’s the sound of you learning.” She had heard and recognized the pattern of Robert’s brain revving up by voicing his resistance, getting it out in the open so that he could clear the way for the learning to happen.

In Seven and a Half Lessons About the Brain, Lisa Feldman Barrett describes the brain as a “predicting organ.”8 My colleague had tapped into what Robert’s brain sounded like as it made a prediction of what he would experience in the next 40 minutes. Robert’s brain remembered that at 9 a.m. every weekday, he was in algebra class; his teachers expected that he would exert effort to comprehend and remember some information; and that in the past, that effort had not led to satisfactory results. Robert’s brain was rapidly seeking ways to avoid this unproductive energy expense. His brain had learned that whining and complaining sometimes earned him time away from the task, often enough that it was worth expending some energy to see if he could avoid the task this time.

Once my colleague identified Robert’s pattern, we could see and hear other students’ learning routines. Some seemed helpful—getting materials neatly stacked on a desk or finding a compatible partner to work with. Others seemed less so—bathroom trips, asking someone else for pencil and paper, putting heads down on desks. Yet when we could identify these patterns, frame the behaviors, annoying or not, in this way—that’s the sound or sight of this student learning—we became more tolerant of these behaviors and less likely to see them as disruptive. We could privately ask students if they found the behaviors were truly helpful in kick-starting the learning process. With a change in our perspective about these behaviors, we could sometimes help students create better, more efficient patterns leading to more productive work routines.

So, What Do We Do to Help Children Develop Effective Patterns?

Remember what it is like to be a beginner, perhaps by attempting a brand-new skill yourself. What does it feel like when you don’t know exactly what to do when or how?

If you have a reluctant learner at home, spend a few days observing how they approach homework time. Notice the behaviors that occur at the beginning of the session, midsession, and the conclusion. Are there avoidance behaviors at the start? What are they? Does concentration wane halfway through? Does your learner shift to daydreaming, or restless movements, or leaving the area altogether? Is there a rush when the end is in sight? Do papers get filed or shoved higgledy-piggledy into the backpack or left on the desk? Which patterns are useful? Which are not?

Once you have identified some patterns, have a talk with your learner about what you have observed. Discuss which patterns seem helpful and which do not. For example, it may surprise you to learn that, although it doesn’t appeal to you, walking in circles while thinking actually helps your child improve concentration. Choose one pattern that your child identifies as not helpful and help your child design a more productive alternative.

For example, if getting up repeatedly to find needed materials derails your child, what can be done to eliminate those disruptions? Maybe putting a range of supplies in a bin that is kept near the homework desk would be an answer. Or if homework is frequently completed but left at home, set a new pattern. Your child repeats the mantra “Homework is finished only when it is in the homework file,” and a trusted partner checks every day for three weeks to make sure the new pattern is set. Be open to suggestions even if they don’t seem plausible to you.

Let your child direct the process. Your most helpful stance is to ask if the experiment has been successful with the understanding that both of you need to agree on its success. Once that new pattern is solidly in place, select another problem pattern and try to address it.

This approach works well not only for homework but for chores, instrument practice, work schedules, and in any number of other contexts.

RECOGNIZE THE ALTERNATIVES

As an instructional coach, I was often in classrooms to observe the learning process and to support teachers as they went about creating their learning communities. Sometimes, if a teacher was called away, I served as an impromptu substitute, continuing a lesson for a few minutes while the teacher was out of the room. One day I was in a roomful of kindergarteners when the teacher needed to step out of the room. The lesson was about shapes, and we were discussing circles. Since the children seemed antsy, I thought they needed to move a little. I invited them all to stand up and make a big circle with their arms.

As I demonstrated with my own arms, I had visions of all these beautiful children beaming up at me with their arms in circles, feeling very circular and knowing exactly what a circle was. What happened next was mind-boggling. These kindergarteners were feeling so circular they began to swing their arms, bodies, and legs around and around, bumping into each other, knocking over chairs, and somehow stepping on each other’s fingers and toes. In two seconds, the room was chaos. What went wrong? Exactly that. I had failed to predict what could go wrong. I had failed to get into the mind of a kindergartener.

In How Children Succeed, Paul Tough introduces us to Elizabeth Spiegel, a middle school chess teacher in Brooklyn. Spiegel’s chess teams were incredibly successful because, as Tough notes, she taught her students to “resist the temptation to pursue an immediately attractive move”—think kindergarteners with their arms in circles. Instead, she taught her students to look for alternative solutions and new and creative ideas. Her students learned not to hide from what could go wrong but to go looking for it. After each chess game, won or lost, Spiegel and her students replayed the game, move by move, analyzing key turning points in the game, thinking about what would have been a better move and what would have happened if that better choice had been made. Spiegel helped her students get comfortable with what is inherently uncomfortable: staring down your mistakes.9

So, What Do We Do to Help Children Recognize Alternatives?

Model thinking through a better move. When a project doesn’t work out, you miss a deadline, or you forget a friend’s birthday, think out loud about where you went wrong. Ask yourself what would be a better move: How could I do this better? Let your children see the process in action.

When things go well, ask why they went well. What decisions were made, or what strategies were used to ensure that the project, activity, or game was a success. Talk about how those decisions and strategies can be replicated and carried over into other areas of life.

SWIM BUDDIES

A conversation I had with a colleague many years ago has stuck with me, long after I have forgotten other details about our work situation. Her teenage daughter was doing typical teenage daughter things for the time, like hanging out at the mall, going to parties, and visiting friends’ homes with varying degrees of parental supervision. My colleague and her daughter had developed a unique system for handling these social opportunities. They had discussed each of her friends and classified them into two groups: those who had good sense and those who didn’t. No one was banned or shunned, but wherever the friends went, there had to be more in the good-sense group than in the bad-sense group. If the groups were out of balance and the have-nots were in the majority, the daughter needed to recruit enough good-sense friends to tip the balance.

Looking back, I can see that my colleague was creating a swim buddy system for her daughter. Her message was this: surround yourself with people whom you can count on to help you do the right thing. In the adolescent years with a brain wired for reward more than pain, having swim buddies who support your desire to exercise caution and good sense is extremely practical. It eliminates the need for the parent always to be in control and calling the shots, and it helps the adolescent develop guardrails and learn independence.

A corollary to the swim buddy system is the trusted-advisor system. Every child should be able to name several adults outside the family unit they count as trusted advisors. Teachers, faith group leaders, coaches, and parents of friends are all possible candidates. We knew that our young son had learned this concept when, as a Cub Scout, he entered the Pinewood Derby. At the time, we had no power tools at home, so he carefully used a handsaw, sandpaper, and a hammer to build his car, under my supervision, but without much technical input, since I didn’t have any to share. His efforts resulted in race times that placed him in the top three of his pack and earned a spot in the District Pinewood Derby.

On the day of the district meet, in the first heat, his car sped down the track, hit the bumper at the end, bounced back, and lost a wheel. We were dismayed. Our son, however, was not. He calmly picked up the car and the stray wheel, looked around the room and headed our way. We had no idea what to do next. Fortunately, our son did not come to us for help. He was actually headed for his trusted advisor, the assistant Cub Scout leader, who had thought about what could go wrong at the Pinewood Derby, and who had brought a toolkit with him. Together, they assessed the situation, our son made a repair, and he was ready for the next heat. I do not remember the outcome of the event, which surely means his car did not end up in first place. I do remember that we were extremely grateful to the leader who thought about what could go wrong and to our son who wisely used his trusted advisors.

So, What Do We Do?

Discuss with your child how impulsiveness, a temperance issue, can lead to poor decision-making, and poor decision-making can lead to hurtful, sometimes even dangerous, outcomes. Talk about children you know who are inclined to be impulsive and make poor choices. Then talk about how helpful it is to have more friends around to support you in making good choices. Come to an agreement about how your child should cope in situations where the poor decision makers outweigh the good decision makers.

Ask what your child might do in an emergency situation. What if parents or caregivers aren’t available for some reason? Which adults might your child reach out to for help? Make sure your child has a list of trusted adult advisors who can be counted on for help and advice. No trusted-advisor list? Think about ways to connect your child to competent, caring adults. Big Brothers and Big Sisters, Scouting or Guides, faith groups, recreational sports, school clubs, or activities are some structured relationships that might be helpful. Informal relationships with neighbors and friends’ parents are also good candidates for trusted advisors.

Make sure your child knows that it is a mark of intelligence and maturity, not weakness, to ask for help when needed.

RESTORATIVE PRACTICES

When I was teaching in a middle school, the principal stopped me in the hall one day to let me know that one of my students had been suspended.

“We found cigarettes in his locker. He says his dad borrowed his coat and left them in his pocket, but I’m not buying it,” the principal said. “He’s out for three days.”

I asked, “Was he smoking at school?”

“No, but I won’t have any student bringing illegal substances into my school.”

I responded, “Isn’t it his school too? How is he supposed to learn if he’s not in school? And how do you know they aren’t his dad’s? And if they are Sam’s, shouldn’t we help him? I mean, he shouldn’t be smoking! No one should! And if he’s at home, isn’t he just going to have more opportunity to smoke? Isn’t that the real problem?”

The principal looked at me with annoyance. “I could have given him five days, you know.”

On his return to school after his suspension, Sam was behind in all his classes, overwhelmed by trying to catch up and angry with all of the adults at the school. The principal’s strong stance, however, was secure.

Had I known about restorative practices at the time, I might have had a more productive conversation with the principal. It would have centered around who was being harmed because Sam had cigarettes in his pocket and because he was most probably smoking somewhere, though not at school. We would have discussed how we could help Sam and all the other students who might try smoking. Maybe we could have had a productive meeting with Sam’s parents, who might very well have been the source of the cigarettes. Sam would definitely be part of these conversations because he was at the heart of the issue. Unfortunately for all of us, restorative practices were not part of our culture, and we were left with the consequences of a broken system.

The concept of restorative practices has deep roots in many cultural traditions. Today, we are looking back to these deep roots to help us create a “civil society that pursues the need for individual human dignity through the development of more just communal engagement and social structures,” according to John Baile of the International Institute for Restorative Practices. Baile’s work at the institute and his review of restorative practices scholarship reveals “three areas of universal human need. These are the needs to belong, to have voice, and to have agency.”10 Sounds a lot like “I belong. I matter, and I make a difference.”

In response to the mass incarceration of convicted individuals as a result of “tough on crime” legislation in the United States, many organizations in the country and the world have implemented restorative justice practices in the criminal justice system.11 Such practices provide offenders and their victims the opportunity to meet, hear each other’s perspectives, and possibly develop a plan in which the offenders make some sort of restitution for the harm they have caused.

In a similar vein, schools have turned away from those zero-tolerance policies that resulted in record rates of suspensions and expulsions but not in more acceptable behaviors, better test scores, or improved sense of community. Instead, schools are implementing an “approach to behavior management and youth development that focuses both on intensive proactive relationship development and responding to misbehavior as harm done to relationships”12—in other words, restorative justice practices.

At the heart of the restorative practices process is the recognition of the responsibility of the individual to the community, and vice versa. There are both proactive practices of community and relationship building and restorative practices of repair and atonement. In schools, routines such as community circles help build a sense of trust and care in the classroom community. When trust has been broken and harm has occurred, those involved meet and discuss the wrong and how it can be repaired. The following restorative questions are used:

![]() What happened?

What happened?

![]() What were you thinking about at the time?

What were you thinking about at the time?

![]() What have you thought about since?

What have you thought about since?

![]() Who has been affected and in what way?

Who has been affected and in what way?

![]() What’s been the hardest thing for you?

What’s been the hardest thing for you?

![]() What needs to happen to make things right?13

What needs to happen to make things right?13

Those who were affected by the poor choices may be asked these questions:

![]() When you realized what happened, what did you think?

When you realized what happened, what did you think?

![]() How did these insights affect you and others?

How did these insights affect you and others?

![]() What was the hardest issue to resolve?

What was the hardest issue to resolve?

![]() How can you make things right?14

How can you make things right?14

These conversations can range from informal to formal and from quick to lengthy, depending on the number of people involved, the context, and the degree of harm committed. But inherent to all these conversations is this consideration: “Human beings are happier, more cooperative, more productive and more likely to make positive changes in their behavior when those in positions of authority do things with them rather than to them or for them.”15

So, What Do We Do to Promote Restorative Practices?

![]() Be proactive. Implement a circle time to discuss issues that are important to your family.

Be proactive. Implement a circle time to discuss issues that are important to your family.

![]() Create norms about how and when circle time happens and how to be sure every voice is heard.

Create norms about how and when circle time happens and how to be sure every voice is heard.

![]() Be responsive. When harm has occurred, use the restorative questions to guide your discussion and your actions.

Be responsive. When harm has occurred, use the restorative questions to guide your discussion and your actions.

![]() Remember that “each of us is more than the worst thing we have ever done.”16

Remember that “each of us is more than the worst thing we have ever done.”16

![]() Be curious.

Be curious.

Find out more about restorative practices at www.iirp.edu.

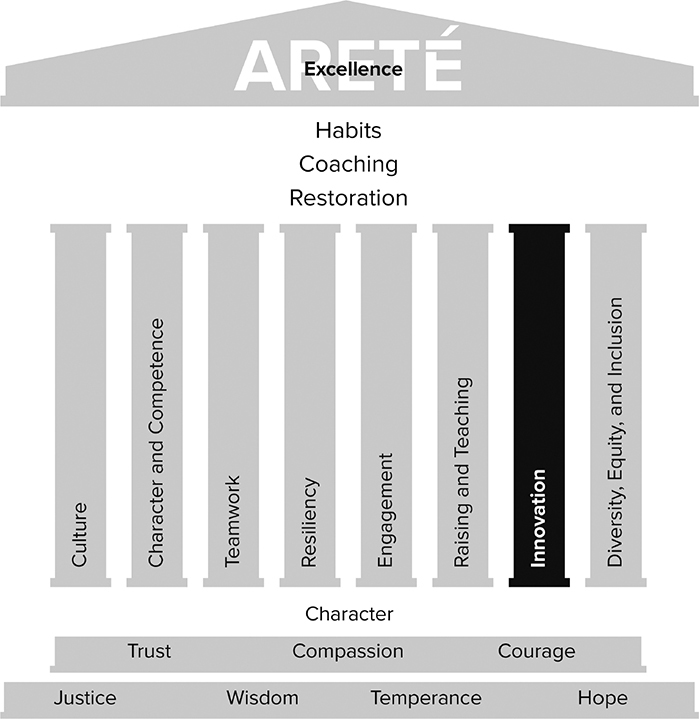

This focus on restoring trust replicates the importance of developing virtue-based cultures in organizations that is so critical to encouraging high performance. In raising children, as in leading organizations, when you get better at who you are, you get better at what you do. And the added value of raising good, resilient children is that it sets up the societies they will populate when grown to be the kind of worlds we all covet—worlds grounded in trust, compassion, wisdom, hope, temperance, and justice.

Julie Rea is an experienced teacher and thinker about virtue-based performance. The use of the first-person voice in this chapter reflects her expert observations and experiences.