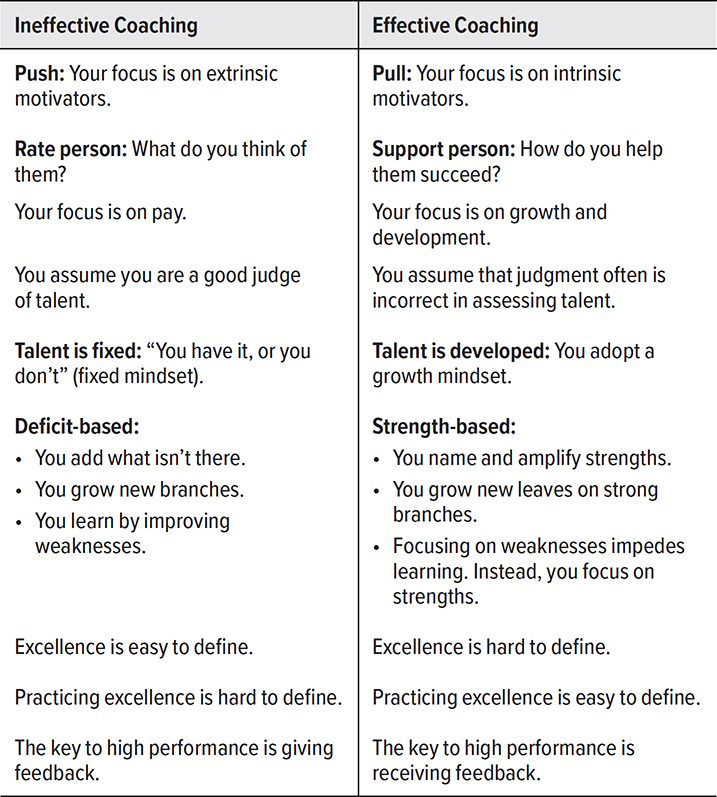

COACHING

Coaches have to watch for what they don’t want to see and listen to what they don’t want to hear.1

—JOHN MADDEN

In 1875, the first Yale-Harvard football game was played. Yale hired Walter Camp, the first college football head coach. Camp created position coaches to preplan every game, develop players, and track performance. On the other side of the field, Harvard competed based on the British approach—players, not coaches, manage the team. Over the next three decades, Yale beat Harvard all but four times. After 30 years, Harvard hired a coach. About a century and half after that football game, the facts are in—coaching and deliberate practice improve performance not just in athletics but in business, the military, and healthcare.

Atul Gawande, experienced surgeon, author, and healthcare expert, wondered how people get better at what they do. Most people go to school to get better and then manage their own growth after graduation. How people get better in sports is different. Everyone needs a coach no matter how good they are. This insight led Gawande to have a coach observe one of his surgeries. Since the surgery went well, he didn’t think the coach would have much to say. But the coach had a lot to say. He asked Gawande if he was aware during the surgery that the light had swung away from the wound. The coach watched him operate from reflected light for half an hour. The coach observed Gawande sometimes put his elbow in the air rather than at his side where he is more in control. His flying elbow also blocked the surgical team’s view. Gawande didn’t necessarily enjoy being observed. He did appreciate that coaching improved his performance as measured by a decrease in surgical complications.2

The purpose of coaching is to help people do their best, make better decisions, add more value, and strengthen their relationships with colleagues, customers, patients, students, and athletes.

Lots of evidence shows that when done well, coaching pays off. For example, MIT has reported that entrepreneurs who are well coached are 7 times more likely to raise funds and 3.5 times more likely to grow a business.3 The Air Force Academy has reported that about 95 percent of cadets who were coached to develop virtue made progress on their goals; and about 95 percent of their coaches agreed they had made progress.4 At Parker Hannifin, teams that integrated virtue into performance metrics reported they achieved their goals three months after working with a coach, and their coaches agreed.

We don’t always understand the issues that hold us back, and we don’t always know how to fix those issues. Research has shown that effective coaching will likely lead to moderate to large change in performance, assuming that a leader is coachable. If an organization has the will and wherewithal, coaching works for the top of the pyramid. Yet, coaching is too expensive to be scaled to middle and frontline leaders. However, as in educating our kids (Chapter 8), swim buddies can be scaled across the organization.

About 5,000 sailors apply to be a Navy SEAL, of whom 1,000 are selected. Of the 1,000 selected, 200 or fewer become SEALs. A critical part of the training is to understand that you can’t become a SEAL on your own. You need help. For this reason, cadets are told on the first morning of training to get a “swim buddy” before lunch. If after lunch, the cadet didn’t find a swim buddy, they are told to “get sandy.” “Getting sandy” means that the cadet does pushups on the beach until they resemble a sand-caked donut. Why all the fuss over swim buddies? Swim buddies help each other succeed. Swim buddies look out for each other.5 Swim buddies are scalable.

Imagine an organization that encourages swim buddies and then trains them in effective coaching. This vision is worth consideration since about 70 percent of the variance in engagement is due to the direct leader. Leaders want engaged teammates, though they don’t always understand the forces that restrain discretionary effort or how to fix these issues. The concept of swim buddies offers a scalable way to help leaders at all levels increase teammate engagement.

HOW DO PEOPLE LEARN BEST?

If we are going to help people grow, then we need to understand how people learn best. Some might say that constructive feedback is essential. Leaders need to give candid feedback and have difficult conversations. Well, not so fast. Rater error and neurology make clear that well-meaning advice often doesn’t consider the biology of the fight-flight-freeze response and the limitation of feedback:

1. Feedback: “I told them. They didn’t listen.” So, let’s assume that we think our advice is nothing short of amazing. What does the evidence have to say about feedback? Decades of research has shown that about 50 percent of your rating says far more about you than the person you rated. Too often, the giver of feedback has a higher opinion of their insights than the receiver of feedback.

2. Fight-flight-freeze: Criticism activates the primitive part of our brain, the amygdala—the fight, flight, or freeze part of our brain. Under conditions of fear and uncertainty, the neurological challenge is that our brain is on guard when we are judged by people we don’t trust. It is useful to know that trust deactivates the primitive brain and activates the thinking brain (prefrontal cortex)—which means we are not on guard. This isn’t to suggest we are victims of the primitive brain. We can still look for insights even when we disagree with someone’s feedback. We can wonder how our behavior gave someone an impression that didn’t serve either of us well, even though we disagree with their reaction.

3. Flaws: Focusing on performance gaps doesn’t enable learning. It impedes learning. Neurologically, we grow more in areas of strength because we already have thickets of synaptic connections. Of course, this doesn’t mean that we should ignore weaknesses, especially a fatal flaw that continually affects our relationships negatively. It just means that we should lead with strengths, even when taking on a weakness, considering how our strengths can positively contribute.

This isn’t to suggest that advice doesn’t have merit, especially in predictable conditions. Pilots use checklists for good reason. There are proven ways to take off, fly, and land a plane safely. Mimicking the success in commercial aviation, surgical teams now use checklists for good reason. These are proven ways to reduce medical errors and infections. Known problem, known solution; stick with the script. However, what’s the playbook for a once-in-a-century global pandemic?

WHAT COACHING IS AND IS NOT

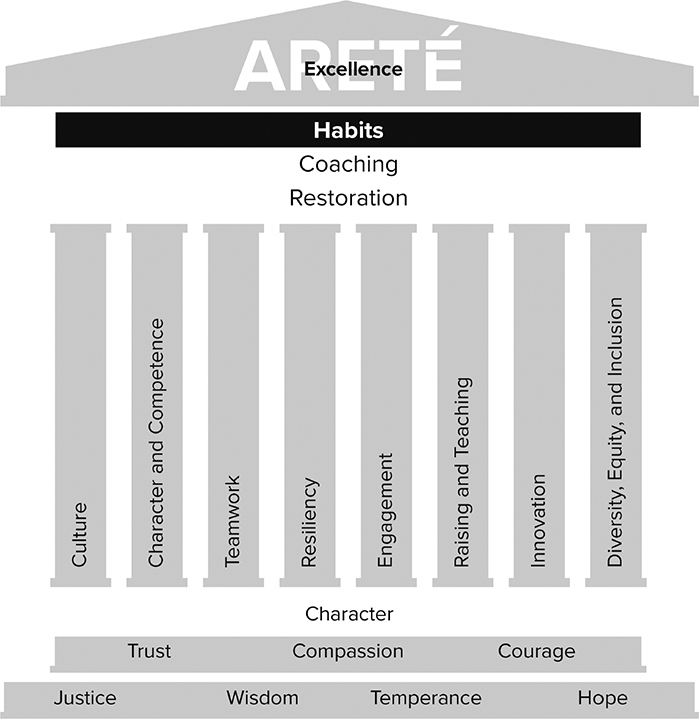

Let’s start by being clear that coaching isn’t consulting, managing, mentoring, or therapy. Certainly, each of these roles could rely on coaching at times. Yet, coaching is different from all of those. Table 12.1 details how the roles and relationships of consultant, manager, mentor, and therapist differ from those of a coach.

Table 12.1 How the Roles and Relationships of Consultant, Manager, Mentor, and Therapist Differ from Those of a Coach

CONSIDER 25/75 AS THE AIM OF COACHING

Recall the 25/75 rule coined by Michael Matthews, professor of psychology at West Point. About 25 percent of the variance in human performance can be explained by cognitive factors, and 75 percent of the variance is explained by non-cognitive factors that can be organized by 3Cs:

1. Character: Virtue

2. Challenge: Resilience defined by bouncing back from setbacks

3. Commitment: Grit defined by persisting through challenges to complete a long-term goal

Think about this for a minute. The 3Cs explain about 75 percent of the variance in human performance, and all three are within our control. Yet, the 3Cs are not on the radar screen of most organizations. This is a significant lost opportunity for two reasons. First, the 3Cs are the biggest drivers of human performance and are trainable. Second, the growing influence of artificial intelligence raises an increasingly urgent question: what can we do that a computer can’t? The answer is that we can become better humans by developing our 3Cs, which a computer can’t do.

We live in a world with plenty to fear: global pandemics, economic volatility, despots, injustice, and climate change. Sometimes, our experiences are scary, and we fear the potential consequences that confront us with good reason. After all, it isn’t paranoia when they are really after you! What will happen to us is not ours to decide. But how we respond is absolutely for us to decide. While we can’t predict the future with any confidence, we can predict that virtue has served people independent of circumstances for thousands of years.

If you want to endure and perhaps even grow from adversity, start with who, not what. Our identity—who we are—is tied to character, challenge, and commitment, not job titles. Of course, coaching for competence has value and might be just what someone needs. In fact, improving a competency is often a safe place to start a coaching relationship. Just keep in mind that character offers a two-for-one benefit—it is a performance multiplier and a reputational protector. It is our character that is in our control and that defines us throughout our life. As Heraclitus said, “Character is destiny.”6 Better humans, better performance.

COMMON COACHING CHALLENGES

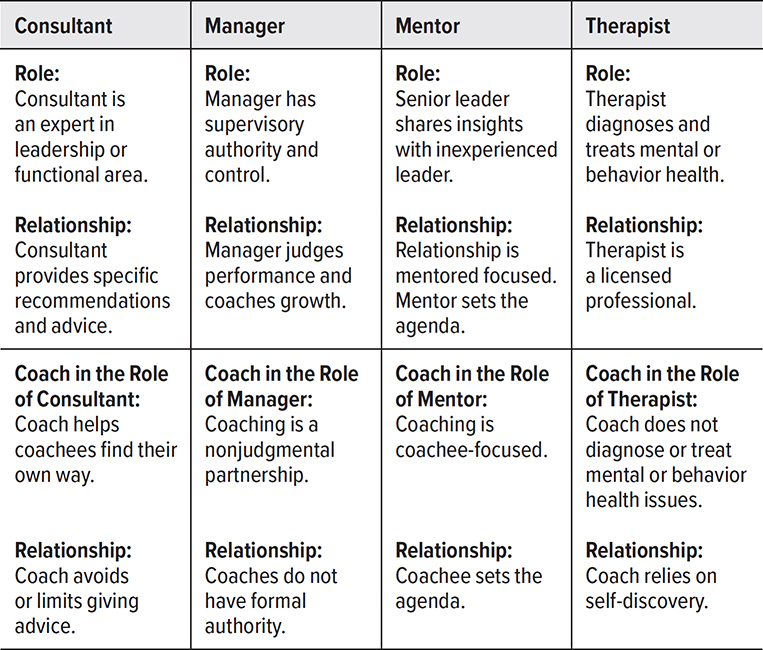

What is not always understood are the three common coaching challenges listed in Table 12.2.

Table 12.2 Three Common Coaching Challenges

WHY DO INCOMPETENT PEOPLE THINK THEY ARE AMAZING?

Socrates said the principal goal in life is self-knowledge. He went on to say that self-deception is the principal barrier to self-knowledge. Our infinite capacity to self-deceive includes an area of research known as the Dunning-Kruger effect. This research is named after the professors who addressed the question, why do incompetent people think they are amazing? Loads of studies have revealed that we frequently overrate our abilities even when our experience is limited. Here are some entertaining examples:

![]() 32 percent of software engineers in one company and 42 percent in another rated themselves in top 5 percent of all software engineers.

32 percent of software engineers in one company and 42 percent in another rated themselves in top 5 percent of all software engineers.

![]() 88 percent of drivers believe they have above average driving skills.

88 percent of drivers believe they have above average driving skills.

![]() A debate team in the bottom 20 percent in performance thought they were winning 60 percent of their debates.7

A debate team in the bottom 20 percent in performance thought they were winning 60 percent of their debates.7

People with limited ability consistently overrate their expertise in fields as diverse as math, chess, ethics, and music.

When we are inexperienced, we lack the knowledge to understand what excellence looks like, and we lack the expertise to catch and correct our own errors. The good news is that once we learn what good looks like, we can recalibrate our abilities.

Experts confront a different blind spot: the curse of knowledge. They know they have expertise, but often they don’t perceive how unusual their abilities are. They have been so good for so long that they have forgotten what it was like to be a beginner. Remember the discussion of the Navy SEALs and the baseball coaches (Chapter 5).

How we respond to rookie or expert mistakes depends on where we fall on the arrogance-humility spectrum. On one end of this spectrum, stubbornness + ignorance = arrogance. New insights and information flow off the arrogant like the proverbial water off a duck’s back. When mistakes are made, denial, blame, and defensiveness kick in. Coaching won’t easily crack the hard shell of an unreflective arrogant person.

On the other end of the spectrum is humility, which C. S. Lewis defined this way, “Humility is not thinking less of yourself; it’s thinking of yourself less.”8

Vulnerability is the close cousin of humility, defined as the courage to step into discomfort and struggle. Predictably, vulnerability isn’t something that we necessarily enjoy though it leads to mental toughness and mental agility.

Importantly, vulnerability and humility are trainable skills. Both open far more options to us than arrogance does. In contrast to the arrogant person who may be headstrong when it comes to coaching, coaching does a world of good for a humble person who is willing to seek advice, even when feedback is hard to hear.

KEYS TO EFFECTIVE COACHING

The simple skill of talking less and listening more, of telling less and asking more, is stunningly difficult to do. As if this weren’t enough, let’s add one more layer of complexity: the person being coached. At its core, coaching is very personal—helping people achieve what they feel is important in their life.

So, life and work are interdependent. When we support a person’s desire to deepen relationships with family and friends, this effort spills over to deepen relationships with customers and colleagues. Since coaching is harder than it seems, let’s focus on coaching 101—empathy, questions, and listening.

Empathy

Empathy is easy enough to understand. Put ourselves in someone else’s shoes. However, it is not always easy to put the needs of another person before our own. It is especially hard to imagine our way into another person’s experiences. It is doubly hard to put ourselves in someone’s shoes when nothing in our background comes close to what they are experiencing.

Empathy is the front door of compassion, which demands even more of us—relieve another person’s suffering. Working our way through suffering is arguably the hardest work of all and comes with no quick fixes. It takes time to both acknowledge pain and to grow from pain. We can learn to bounce back or even grow from suffering when we have at least one person who is empathic, asks appropriate questions, and listens to us.

Questions

Open-ended questions are a way to demonstrate empathy. The root word of question is quest. Questions put us on a journey to understand what good means to someone. There is certainly nothing robotic about asking good questions. That said, it is helpful to have guidelines on what good questions look like. Here are some open-ended questions adapted from Michael Stanier:

1. What is on your mind?

![]() The purpose of this question is to define the issue that is important to the coachee.

The purpose of this question is to define the issue that is important to the coachee.

2. What challenges are you facing?

![]() Explore whether the issue is related to projects, people, or patterns:

Explore whether the issue is related to projects, people, or patterns:

![]() Projects: Any challenges around one of your projects?

Projects: Any challenges around one of your projects?

![]() People: Any challenges with team members, customers, patients, partners?

People: Any challenges with team members, customers, patients, partners?

![]() Patterns: Any personal challenges? Patterns are potentially the greatest opportunities for growth, especially when the real challenge is strengthening one of the virtues.

Patterns: Any personal challenges? Patterns are potentially the greatest opportunities for growth, especially when the real challenge is strengthening one of the virtues.

3. If you had to pick one issue to focus on, which one would be the greatest challenge?

![]() Often our concerns are all over the map, so confusion is to be expected. If we are clear about our challenges, we may not need a coach. When things are foggy, a coach can help. In fact, the role of the coach is to help a person clear the fog so they can focus on things that matter.

Often our concerns are all over the map, so confusion is to be expected. If we are clear about our challenges, we may not need a coach. When things are foggy, a coach can help. In fact, the role of the coach is to help a person clear the fog so they can focus on things that matter.

4. How important is this to you?

![]() This is a diagnostic question: does the person get it, want it, or do it?

This is a diagnostic question: does the person get it, want it, or do it?

![]() Get it: Does the person understand the issue at hand? If not, ask probing questions until they get it. If so, move to want-it questions.

Get it: Does the person understand the issue at hand? If not, ask probing questions until they get it. If so, move to want-it questions.

![]() Want it: Is the person motivated to change? If not, no worries; wait until they are. If they are motivated and get it, then move to do-it questions.

Want it: Is the person motivated to change? If not, no worries; wait until they are. If they are motivated and get it, then move to do-it questions.

![]() Do it: If the person gets it and wants it, now it’s time for deliberate practice. If there is progress, then declare victory. If not, keep practicing.

Do it: If the person gets it and wants it, now it’s time for deliberate practice. If there is progress, then declare victory. If not, keep practicing.

5. What does good look like?

![]() This is a positively framed question to get clear on what good means to someone. Once we are clear about the desired end state, then we can put deliberate practice to work.

This is a positively framed question to get clear on what good means to someone. Once we are clear about the desired end state, then we can put deliberate practice to work.

6. What restraints limit your ability to make progress toward your goal?

![]() Rather than push someone to practice virtue, assume they already want to practice virtue. Define the restraining forces that inhibit their goal, and discuss how these forces can be reduced or eliminated.

Rather than push someone to practice virtue, assume they already want to practice virtue. Define the restraining forces that inhibit their goal, and discuss how these forces can be reduced or eliminated.

7. How would you apply deliberate practice to achieve your goal?

![]() Goal: Define a goal that matters to you, that is specific, and that is focused.

Goal: Define a goal that matters to you, that is specific, and that is focused.

![]() Effort: Define the level of effort that will be needed to achieve your goal, including how to reduce or eliminate restraining forces rather than relying on willpower.

Effort: Define the level of effort that will be needed to achieve your goal, including how to reduce or eliminate restraining forces rather than relying on willpower.

![]() Learning partner: Identify someone who is empathetic, asks good questions, and listens well.

Learning partner: Identify someone who is empathetic, asks good questions, and listens well.

![]() Reflect and refine:

Reflect and refine:

![]() Reflect on how well you leveraged your strengths.

Reflect on how well you leveraged your strengths.

![]() Refine how to leverage your strengths more.

Refine how to leverage your strengths more.

![]() Meet three to five times to review progress on your deliberate practice:

Meet three to five times to review progress on your deliberate practice:

![]() At the last session, answer whether you made progress toward your goal.

At the last session, answer whether you made progress toward your goal.

![]() Answer whether your learning partner thinks you made progress toward your goal.

Answer whether your learning partner thinks you made progress toward your goal.

8. What was most useful for you?

![]() This question gives the coach feedback about what worked and what didn’t work.9

This question gives the coach feedback about what worked and what didn’t work.9

Listening

It takes skill to understand rather than be understood. To listen well, we need to understand the difference between poor (level 1), average (level 2), and excellent (level 3) listening:

![]() Level 1 listening: While the other person is talking, think about what you want to say. Wait for the other person to take a breath, or better yet, talk over them, so you can speak your mind. You might be coming out of your shoes to tell the person about your experiences or your problems. It’s no surprise that this level of listening isn’t even within hailing distance of effective coaching.

Level 1 listening: While the other person is talking, think about what you want to say. Wait for the other person to take a breath, or better yet, talk over them, so you can speak your mind. You might be coming out of your shoes to tell the person about your experiences or your problems. It’s no surprise that this level of listening isn’t even within hailing distance of effective coaching.

![]() Level 2 listening: Coaches stick to what and how, not why. Why is a judgment question. While why is appropriate to ask in other settings, it isn’t when it comes to coaching. Since the agenda is driven by the coachee, they own the why question. The coach toggles back and forth between probe and validate to help clarify goals and effort by asking questions such as these:

Level 2 listening: Coaches stick to what and how, not why. Why is a judgment question. While why is appropriate to ask in other settings, it isn’t when it comes to coaching. Since the agenda is driven by the coachee, they own the why question. The coach toggles back and forth between probe and validate to help clarify goals and effort by asking questions such as these:

![]() What would that look like for you?

What would that look like for you?

![]() How would you do that?

How would you do that?

![]() Level 3 listening: Avoid tripping over the obvious by listening carefully for what isn’t being said. Ask open-ended and clarifying questions to make sure you understand what the person is thinking, saying, and feeling. Rely on questions that help a person overcome adversity rather than fixate on self-esteem. Rely on questions that help leverage strengths and manage weaknesses.

Level 3 listening: Avoid tripping over the obvious by listening carefully for what isn’t being said. Ask open-ended and clarifying questions to make sure you understand what the person is thinking, saying, and feeling. Rely on questions that help a person overcome adversity rather than fixate on self-esteem. Rely on questions that help leverage strengths and manage weaknesses.

Here’s the thing. Programs don’t change people. People who are empathic, who ask good questions, and who listen carefully change people.

WHAT DOES GOOD COACHING LOOK LIKE?

If a coach helps a leader read a balance sheet or understand project management, it is relatively easy to measure that. If the coach helps a leader by emphasizing their strengths, by learning to manage fear, by cultivating insights about their purpose and passion, how do we measure the benefits of that?

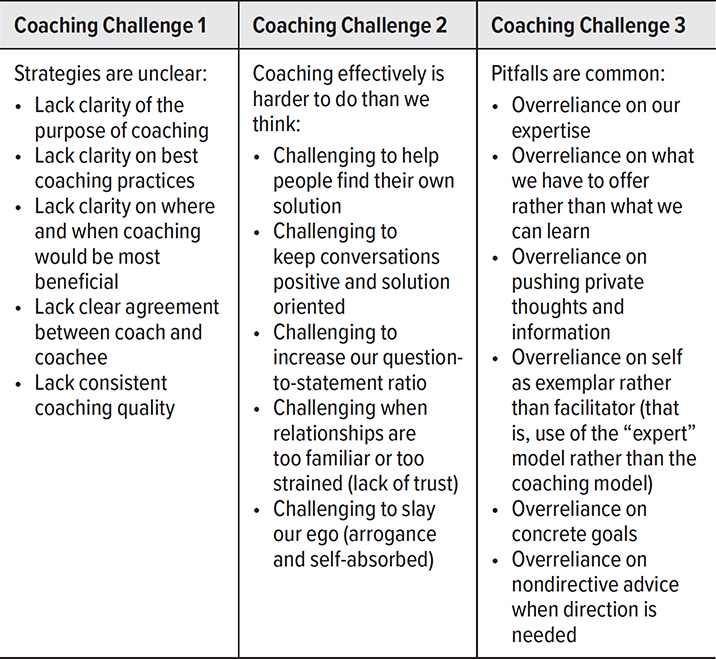

Consider that people are not fully engaged when they are frozen by fear. People step toward their potential by operating from their purpose of who they want to be and the contribution they want to make. This requires self-reflection, which is an underdeveloped capacity in many leaders who are generally action-oriented people. As shown in Table 12.3, good coaching promotes self-reflection while ineffective coaching results in unrealized potential.

Table 12.3 Features of Effective Versus Ineffective Coaching

Effective coaching works best in organizations that view vulnerability as an act of courage. A healthy culture acknowledges that we will never be error free and we can always get better. At the same time, no matter how good someone is, they have blind spots. In contrast, a toxic culture weaponizes vulnerability. Toxic cultures hide, deny, and punish mistakes rather than own and grow from mistakes.