chapter 8

Rewarding your members

In 2018, I was hired to present to a small group of senior executives at a software company on the topic of communities. One of them wanted to start a community for the organisation but was struggling to overcome objections of other senior leaders. He was hoping an outsider could answer some of their questions.

About halfway through my presentation, I was abruptly interrupted with a dismissive question:

‘So, in your world, you think our customers are just going to help each other and share their resources for free? What’s in it for them?’

As I began explaining that people do things in a community for a feeling of helpfulness, belonging, and building a reputation, he interrupted me (again!). The exchange went as follows:

Him: ‘I asked about communities in a WhatsApp group I’m in. A friend of mine at [big software company] said they had tried it and you have to either pay members to answer questions or give them free stuff. Eventually it became too expensive and they shut it down.’

I couldn’t resist the irony of that statement:

Me: ‘Did you pay your friend to give you that information?’

Him (looking confused): ‘Umm, no?’

Me: ‘So why did your friend at [big software company] help you?’

Him (looking more confused): ‘Because he’s my friend and likes to help. Why does this matter?’

I felt I might be breaking through ...

Me: ‘That’s the same as any other community! People like that feeling of helping each other. The more they get to know and like each other, the more they want to help. If people aren’t doing that in his community, I’d guess your friend probably resorted to giving members free stuff too quickly instead of finding out what really motivates them.’

I can’t say I persuaded him, but the other executives did eventually move ahead with creating the community – and they didn’t have to pay their members to participate! Indeed the idea of members volunteering to help a brand without expectation of payment can be a powerful motivator in getting people on board.

Paying members to participate is not just a bad idea that harms their motivation, but (as we’ll soon see) comes ripe with a whole host of legal problems.

Likewise, giving members free stuff (free products, services, or even SWAG) sounds like a good idea. But this is often just payment by a different name. You never want members participating in a community to get free stuff, you want members participating because they want to help others, belong to a group, and build a reputation.

This doesn’t mean you can’t (or shouldn’t) reward members. Rewards can be a very powerful incentive to increase participation and get members to do the kinds of things you want. However, it does mean the rewards you offer members should engender the right kind of feelings in members to perform the right behaviours. More importantly, you should be offering rewards to members which are more valuable than gifts and money.

WARNING – The danger of paying members!

One of my earliest community efforts was managing a video gaming league in the UK. This required a dozen volunteer administrators to help referee matches, update scores, and keep things ticking over. This worked well for a while. Most administrators liked to help and enjoyed the feeling of power that came with the role.

Everything changed when we secured our first corporate sponsorship. I decided to use this money to pay admins who had been working so hard for free. Everything quickly went to hell. Some admins felt they should be paid more based upon their length of service while others felt slighted if they weren’t paid the same as others for their work.

Worse yet, admins began treating it like an exchange. They began putting in the minimum level of work to get paid rather than trying to do their best work. To previously dedicated admins, this volunteering had become an underpaying side job.

Four types of rewards

We touched upon several types of rewards already in Chapter 6 Nurturing superusers in your community. In this chapter, I’m going to break these down into four specific categories, provide examples of each, and then a framework for when to use each type of reward.

The four categories of rewards are reputation, access, influence, and tangible goods. Each of them serves a different purpose at a different time. You can find some examples of each below:

Type | Explanation | Examples |

|---|---|---|

Reputation | This is the reputation members earn and a sense of respect they achieve within the community. |

|

Access | Access to information and benefits other members don’t receive. |

|

Influence | This is their technical permissions within the community which might rise as their ranking increases. |

|

Tangible goods | These are the specific items they gain as a result of being in your community. |

|

As a general principle, the better the rewards you can offer your members the more participation you get. No, this doesn’t mean you need to start handing out cash rewards or other goodies. It might instead mean offering members more access, more opportunities to have status, or more recognition for their contributions (like being featured in the newsletter).

When you’re building a community for a small group it’s relatively simple to offer these rewards. However, when you work for a larger organisation this becomes more difficult. You can’t simply send out an email to your entire customer list celebrating the achievements of your customers. Your marketing team would (understandably) have a problem with that. Typically in a larger organisation you need to build internal support first to be able to offer great rewards. This is the hard part that makes it valuable.

For example, if I want a client to offer top members trial versions of a new product, I need to work with marketing, engineering, and legal teams to make that happen. This takes time, but it makes the community experience a lot better. Before we get to that stage, however, we need to know what rewards to offer, when to offer them, and to whom the rewards need to be offered. This is where the principles of ‘gamification’ come into play.

The practice of gamification

At the beginning of the last decade, some bright spark (probably) looked at how much time we spend playing games and decided to make pretty much everything we do online more like playing a game.

You’ve probably come across a lot of gamification over the past decade. If you’ve taken courses on Khan Academy, Duolingo, or Codeacademy, you might have earned ‘streaks’ for visiting several days in a row or ‘levelled’ up when you completed each chunk of the course. If you’ve been jogging and using Fitbit, you might get stats on how far and fast you ran and how that compares with your best times. Even Starbucks lets you earn points and level up with every purchase through the app.

Gamification isn’t a new idea for communities either. Early pioneers like Amy Jo Kim have been talking about ‘game mechanics’ in communities since the early 2000s.1 What’s different today is the quantity and quality of tools we have available to gamify our communities.

Before the gamification craze, a member’s ‘post count’ (total number of posts) would often appear next to a member’s profile. The more posts you had, the more senior you were presumed to be. This primitive gamification system had an obvious and unfortunate side effect; it motivated members to post as many messages as possible (regardless of their quality).

Luckily, the tools and knowledge we’ve acquired since then mean we can develop far better reward systems. In the same way drug manufacturers can now target drugs at specific protein molecules in the body (instead of flooding the whole body with the same cure), we can now target very specific behaviours and encourage more of them in communities too. And, also like drug companies, we are getting a lot better at dealing with the potential side effects.

What is gamification?

We’re going to use a lot of game terminology in this chapter. If you find this confusing simply remember that we’re really just talking about a system for deciding which rewards to offer to which members (and when). While many aspects of gamification are implemented in large platforms, you can still apply these principles even in the simplest platforms to get the results you want.

Let’s start by clarifying two terms: game mechanics and game dynamic.

A game mechanic is a functional element of playing a game (like points, badges, etc.).

A game dynamic is a state of mind experienced when playing the game (achievement, competition, etc.).

Gamification is the craft of using game mechanics to create dynamics that satisfy human desires and achieve your goals.

Tools for game mechanics

Some platforms let you deploy a wide array of game mechanics within your community. The most common include:

- Points. This is when you let your members earn points for specific behaviours (i.e. starting a discussion might be worth three points and responding to a discussion might be worth one point).

- Levels. Levels are rankings – typically based upon the number of points a member has earned. A newcomer might be on level 1 while a veteran might be on level 50. Levels are often connected to permissions (below).

- Permissions. Permissions are what members are allowed to do in a community. Once members have reached higher levels they might be allowed to help moderate discussions, join private groups, and report problems etc.

- Badges. Badges are visual images which can be displayed on your members’ profiles. Similar to cub scout badges, they reflect achievements within the community (i.e. the ‘initiator badge’ for starting 20 discussions).

- Leaderboards. Leaderboards are a ranked list of members based upon the number of points they earn. Communities often have leaderboards of all-time rankings, based upon the previous 12 months, or within each topic within the community.

- Challenges/missions/trophies. These are awards (often technically badges) you can earn for completing a combined series of behaviours (i.e. if you introduce yourself, post your first discussion, and complete your profile, you might earn the ‘rising star’ award).

- Gifting. Gifting is where members can give each other virtual gifts (often premium accounts, points, virtual goods, or badges). Only a handful of platforms have this (i.e. Reddit).

- Virtual goods. Primarily used in gaming, virtual goods are assets members can collect and use within the community (i.e. a one-time ability to promote their own posts above others).

You will notice that many mechanics interplay with each other. For example, points help determine rankings which determine what rewards members earn. This also isn’t an exhaustive list. Different technologies offer different game mechanics you can deploy. Broadly speaking, the more costly your platform is, the more gamification options you have. Some of the inexpensive platforms (i.e. Facebook/Mighty Networks) have very limited gamification tools available whilst others (i.e. Salesforce and Khoros) offer a more complex array of options.

However, even if game mechanics aren’t built into the community platform you’re using, you can still deploy primitive gamification systems the same way a teacher does in a class. You can manually give members stars and badges either in the community or in a separate system. You can create a spreadsheet and give people points for great contributions or set challenges for members to participate in. Using a low-budget platform doesn’t preclude you from being able to reward your members.

Types of game dynamics

Now we know the mechanics we can deploy, we can think about the dynamics.

Don’t start introducing game mechanics to a community without figuring out the dynamics you’re trying to create (i.e. what do you want members to feel when they participate?). Video game designers aren’t randomly dropping points or levels into any situation. They’re using their mechanics carefully to create a specific feeling.

Some of the most common dynamics include:

- Reward. Members receive rewards based upon behaviours they’ve collected.

- Status. Members can increase their status amongst their peers for participating in the community.

- Achievement. Members feel a sense of achievement and accomplishment based upon their contributions and successes within the community.

- Self-expression. Members can customise their profiles and carefully craft their identity within the community.

- Competition. Members can see how they compare and try to beat other members.

- Altruism.2 Members can send gifts to each other as a thank you for their contributions (or for any other reason they see fit).

Each type of mechanic can create a different type of game dynamic as you can see in the table below.

Game dynamic | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Game mechanic | Reward | Status | Achievement | Competition | Self–expression | Altruism |

Points | X | X | X | |||

Levels | X | X | ||||

Badges | X | X | X | X | ||

Permissions | X | X | X | X | ||

Leaderboards | X | X | ||||

Challenges | X | X | X | X | ||

Virtual goods | X | X | ||||

Gifting | X | X | X | X | ||

Source: Adapted from Kuo and Chuang (2016)3 | ||||||

Unless you know what drives people to participate in your community, it’s impossible to determine the right mechanics. Before you select your game mechanics, you need to be clear about what kind of dynamic you’re trying to create. This is why you need to do your audience research first. You need to know who the community is for and what that audience desires. This research will give you an inkling of what type of dynamic to use.

If you’re leading a community for those affected by cancer, you might realise that altruism and achievement are better dynamics than competition and status. Therefore you would select mechanics such as levels, badges, and letting members award gifts to one another. However, in a customer support community, members might be more motivated to build a reputation and prove their expertise. Thus competition and status might be the ideal fit. You might thus deploy leaderboards, point systems, and create challenges for members to tackle.

Deploying the wrong game mechanic can do considerable harm to a community. If members come to the community for a sense of belonging and you suddenly make them feel like they’re competing against their friends, you’re going to lose a lot of them.

The most powerful rewards take longer to earn

At the core level, gamification works through prompting and reinforcing behaviour. If you take a positive action, you earn a positive reward. But the time and effort it takes to perform the action and speed at which members earn the reward matter.

At the simplest level, the longer the time between taking the action and earning the reward, the less impactful the reward is. However, this is only true with the lowest-value rewards. If the reward is perceived as especially high value, people will spend more effort and energy to achieve it.4 The power of these rewards therefore lasts for longer.

This following table (adapted from one created by Michael Wu, a data scientist)5 shows this well:

Badges | Leaderboards | Trophies | Ranking | Industry reputation | Team reputation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Timeframe | Immediate | Days/weeks | Week/month | Quarterly | Six months | At least a year | Several years |

No. of actions | Gained after a single action | Gained after multiple actions in a short period | Gained after multiple actions over a long period | ||||

Metrics | One-off activities | Combination of behaviours | Reciprocity and team metrics | ||||

Ability to cheat | Easy to cheat | Harder to cheat | Almost impossible to cheat | ||||

Public or private? | Private to the member | Public within the community | Recognised outside of the community | ||||

Implementation | Easy to set up | Difficult to implement | |||||

Longevity | Power fades quickly | Sustains long-term behaviours | |||||

The easiest systems to implement are points and badges. Many community platforms offer these by default. If your platform doesn’t, you can set up a simple system using a spreadsheet, wall chart, or anything else to manually award members points and badges. These are usually gained after single actions in the community, i.e. a single contribution might be worth one point but a response might be worth five points.

However, the power of points and badges fades quickly. Would you really care about having 4000 points instead of 3000 points in a community? Did you really care about getting your 20th gold star in school after your 19th? This is why several studies have shown that points and badges don’t usually create lasting behaviour change alone.6, 7

Instead these are tools to create a dynamic. A dynamic such as a sense of achievement or reaching a higher ranking. These take longer to gain, involve a combination of multiple behaviours, and have a more intangible value. They are also, as we’ll see shortly, far more difficult to ‘cheat’.

However, the biggest reward is usually a good reputation. A great reputation is the hardest thing to earn and yields the most benefits. There are two types of reputation here:

- Personal reputation. You might earn a good reputation through positive contributions to the industry, a sector, or helping out your peers and friends. The best reputations are transferable, i.e. if you’re regarded as a top community member on one platform that reputation is also respected throughout the industry or sector.

- Team reputation. Team reputations are earned by a named group of people within the community (or by the community as a whole). Once a group has a powerful reputation, simply being associated with the group is highly motivating. This is perhaps the most powerful type of reputation but also the most difficult one to create.

Problems with gamification

Perhaps the real question is does gamification truly work?

In all the hype around gamification, it took years for studies to emerge which examined its impact upon behaviour. In 2014 three academics published their review of 24 empirical studies on gamification. Their findings painted a mixed picture. They discovered that while gamification can have positive effects, the effects are dependent on the context and qualities of the user.8

They uncovered two major problems with gamification, each of which you need to successfully mitigate if your gamification efforts are to succeed.

Problem 1: Undermining motivation

The first (and most common) criticism of gamification is that it can undermine your motivation. For example, imagine you have been participating in a community for years. You like the members there, enjoy the feeling of helping others, and love learning more about the topic.

One day, you suddenly find a score against your name, a collection of badges you’re told to earn, and you’re ranked on a leaderboard against your friends. Not only will that undermine your motivation, but it’s likely to cause a whole host of new problems. Do you want the stress of competing against your friends and preserving your reputation every day?

Worse yet, you might discover this new scoring system means your peers now have the ability to edit your posts and they are in a private group you can’t see or know much about. Will you want to keep participating in this kind of community?

This problem was best shown in a 2015 study of gamification in a classroom. Students exposed to gamification were less motivated, less empowered, and less satisfied. Worse yet, leaderboards and subsequent social comparisons were frequently cited for their negative consequences.9

You can also undermine motivation by giving members exactly what they want. When members are participating because they enjoy participating, they are usually making thoughtful, considerate posts in a tone which would most benefit other members. Their guiding star was the satisfaction of others. If you shift that guiding star to boosting their position amongst others, the quality of contributions can suffer. For example, the best way to climb the leaderboard is often to participate more, ask more questions, and pump out as much content as possible – regardless of its quality.10

One study in an employee community showed that while gamification did increase motivation to add more content initially, this declined over time.11 This is also apparent in other studies of gamification.12, 13 Scholars put this down to the novelty effect. Anything new is exciting at first – but once the novelty fades are members genuinely more motivated to participate in the community?14

In another field experiment in 2013,15 a peer-to-peer trading service was updated with badges members can earn from performing a variety of tasks. About 3234 users were randomly assigned into two treatment groups and shown different versions of the badge system. The results showed that simply implementing a badge system did not automatically increase activity. However, those users who monitored their own badges showed increased user activity. In short, it only had an impact upon the types of people who care about things like badges.

Ultimately, gamification is highly contextual and the impact can be temporary, limited, or damaging if it’s not well implemented.

WARNING – It’s hard to turn gamification off!

A quick word of warning.

Once you’ve begun rewarding members, it’s very hard to remove those rewards from members. Members feel they have earned these symbols. If you remove them, you’re going to cause major problems. Even tweaking a system frequently provokes outrage. You should be extremely cautious about adding any game mechanic. You can always add new mechanics if you need them, but it’s hard to take them away.

Problem 2: Cheating the system

The second common problem with gamification (and any reward schemes) is cheating.

It’s pretty much impossible to design a gamification system which is impervious to cheating. Stamping out cheating is like trying to stamp out tax evasion. Almost every policy you introduce also introduces new loopholes and opportunities which are difficult to foresee in advance.

Whenever you put a score next to someone’s name and show them a list of behaviours to increase the score you’re going to get cheating. Cheating typically comes in one of two forms:

- Overposting. The most common type of cheating is when a member contributes as many posts as possible to earn points. These might be short, quick, responses which don’t significantly add anything to the discussion. For example, ‘good post’ or ‘nice idea!’. Sometimes members initiate dozens of new discussions each week or suggest as many new ideas as possible knowing that these behaviours are perhaps more valuable than other behaviours.

This isn’t specifically against the rules, but it begins an arms race where other members have to engage in similar activities to compete. Soon your community will be flooded with low-value activity.

Luckily you have a few tools in your arsenal to fight against this. The most obvious is to tell the member to knock it off and threaten to suspend or remove the member. This can work in smaller communities, but it’s harder in larger communities where you might have dozens of overposters per day and you need to systemise your response.

One approach is to add a ‘downvote’ option. Members who contribute low-quality posts might find they lose points. However, downvotes can also encourage bullying, discourage diversity of debate, and be intimidating for newcomers.16

The more common approach is to skew rewards towards quality over quantity. For example, a reply to a discussion is worth 1 point, but getting a response, a ‘like’, or having an answer marked as the ‘best answer’ might be worth 10 to 50 points. This requires the approval of other members to earn points. In turn, this deters members from trying to rank highly by posts alone. If reaching a new level requires 1000 points, for example, a typical member will sooner give up rather than create 1000 posts.

But this approach also introduces a new problem: collusion.

- Collusion. Collusion is when one or more members work together to increase their standing. In early 2020, one of my clients noticed over half of the places on their leaderboard had been taken by representatives from a single company overnight.

How did they do it?

Somewhat ingeniously, they had looked at the platform we were using, discovered that being endorsed as a product expert by another member was worth a large number of points, and then all endorsed each other as experts. They had also discovered a bug where removing that endorsement didn’t also subtract those points. Thus they could endorse someone, remove that endorsement, and endorse that person again.

It’s relatively rare, but when the rewards for being a top member are extremely valuable (yes, a reputation can be very valuable too), you have to anticipate collusion.

Sometimes this is just a single member creating multiple accounts and rating their own answers highly. Fortunately, most modern platforms can pick up on multiple accounts using a single IP address. More likely it is a genuine collusion, i.e. a small group of members liking and voting positively on each other’s activity to rise up in the rankings.

This is far harder to spot in larger communities. If my client’s members hadn’t got greedy and tried to take every spot in the leaderboard in the same week they might have remained undetected for a lot longer.

Preventing cheating and collusion

There are generally three approaches to prevent collusion (and most types of cheating):

- Don’t make it worth cheating to earn the reward. Cheating is only worthwhile when the reward is worthwhile. When the reward is tangible, such as free products, invites to events etc., then cheating might seem worthwhile to some members. Yet when the reward is intangible – such as building a reputation, getting access to staff, or having moderation powers – cheating is far less worthwhile (because it would take a sustained period of cheating to reap the reward).

Cheating is most common when the rewards are clear and specific. Some communities, such as the Apple community, deliberately leave the rewards of achieving the highest rankings vague.17 If you don’t know what the reward is, why bother cheating? That doesn’t mean they’re not there – it just means you won’t know what they are until you reach that level. This kind of approach inspires true fans eager to find out and deters the bad actors.

- Be vigilant. If members are rising rapidly up the rankings, it’s worth spending a little time checking their contributions and the reactions to their contributions to see if anything is amiss. This is easiest to do in small communities where the sudden rise of a single member is easy to identify and you have the time to investigate their work. It’s far more difficult to do this in larger communities with thousands, even millions, of members climbing the ratings ladder. However, you should still keep an eye on any members rising rapidly up the rankings.

- Get technical. You can develop technical solutions to spot and prevent the types of cheating above. For example, outliers can be flagged automatically for you to pay attention to. Members can be limited in the number of posts they contribute per day – or even have their scoring reduced if they post too many low-quality comments. You might even withhold awarding points if the post doesn’t include enough characters or a member has posted too many times recently. Putting a daily or weekly cap on the number of points a member can earn immediately reduces cheating.

Likewise, if cheating is a serious problem, you can develop tools to prevent members from liking the contributions of the same members too often or to quickly identify reciprocal posting. Technical solutions are costly and time intensive. They best serve as last resorts rather than first options. It’s rare you will need them. However, if you find cheating is undermining the contributions of other members it’s worth investing time and resources into implementing a better solution.

Developing your gamification system

It’s hard to design an entire gamification system from scratch.

To help you get you started, let’s go through a fairly simple gamification system. For simplicity, we’ll use the example of a customer support community where members have questions and people are invited to answer those questions.

Step 1: Decide behaviours to encourage

Before we begin, we need to know precisely what behaviours we wish to stimulate (this comes from the community goals we established in Chapter 1). For the purpose of this example, we have decided our primary target audience for gamification are our core group of superusers (you can just as easily use gamification to target any group, newcomers, veterans, intermediate members etc).

Target audience(s) | Superusers (top community members) |

|---|---|

Desired behaviour | Answer the majority of questions within 24 hours |

We know answering more questions is the critical behaviour and we wish to increase the number of questions answered by superusers. To do this, we need to know what game dynamic to use.

Step 2: Select your game dynamic

We use our personas to select the right dynamic. We might know from our interviews that superusers like feeling a part of our mission and they feel they are amongst the smartest members. So we will be using the achievement and competition dynamics we see below.

Target audience(s) | Superusers (top community members) | |

|---|---|---|

Desired behaviour | Answer the majority of questions within 24 hours | |

Persona | Like feeling part of our mission and consider themselves amongst the smartest members in the community | |

Game dynamic | Competition | Achievement |

Step 3: Select your game mechanics

Now we know the dynamics we’re trying to create, we can start thinking about the mechanics we’re going to use. This table we shared earlier is a good place to start thinking about some of the mechanics you might use to create the right dynamic. You might also want to speak to some of your target members at this stage too to get a sense of how they feel about different mechanics.

In this example, based upon our desire to create achievement and competition dynamics, we might select points, levels, badges, permissions, leaderboards, and challenges. We can add this to our table below:

Target audience(s) | Superusers (top community members) | |

|---|---|---|

Desired behaviour | Answer the majority of questions within 24 hours | |

Persona | Like feeling part of our mission/consider themselves amongst the smartest members in the community | |

Game dynamic | Competition | Achievement |

Game mechanics |

|

|

If this is your first time setting up game mechanics, it’s important to have an idea of the decisions you need to make and some of the mistakes to avoid. To help you out, I’m going to dive a little deeper into the main mechanics and how they can be used effectively.

1 Points

Since many (if not most) gamification systems are based upon points, we first need to determine what behaviours are important and how valuable they are compared to one another.

Don’t agonise too much over the precise values. What matters is how each behaviour relates to one another. For example, what is the value of creating a post compared with answering a question? Is answering a question more valuable than replying to one? If it is, asking a question might be worth three points and replying to a question worth just one.

Likewise, what is the value of sharing a detailed knowledge-based article or having an answer marked as an accepted solution (or best answer) compared with other behaviours?

Developing a point system is handy as it forces you to decide the value of each behaviour. At the time of writing, for example, the default gamification system from Salesforce is as follows:18

Action | Points |

|---|---|

Write a post | 1 |

Write a comment | 1 |

Receive a comment | 5 |

Like something | 1 |

Receive a like | 5 |

Share a post | 1 |

Someone shares your post | 5 |

Mention someone | 1 |

Receive a mention | 5 |

Ask a question | 1 |

Answer a question | 5 |

Receive an answer | 5 |

Mark an answer as ‘best’ | 5 |

20 | |

Endorsing someone for knowledge on a topic | 5 |

Being endorsed for knowledge on a topic | 20 |

This default point system isn’t perfect, but it’s a good place to start. Receiving a response to a contribution is worth five times as many points as creating a post. This encourages people to post good, interesting questions which are likely to gain more responses.

Likewise, answering a question is considered five times more valuable than asking one and having an answer marked as ‘best’ is worth 20 times as many points as writing a comment. This gives a good indication of the behaviours the system is trying to encourage.

WARNING – Be stingy with your points in the beginning!

A key word of warning here. You can always be more generous with points if the system isn’t working, but it’s hard to be less generous when you’re up and running.

If members are used to earning three points for a post and now only earn one you’re likely to reduce their motivation to perform that behaviour. Also if you later decide answering a question is only three times as valuable as asking a question, you can’t change the system without removing points from your members.19 This will upset members who will see their point tally plummet and will result in members losing their levels, status, and privileges.

The only alternative is to inflate points (i.e. make each post worth two points and each response worth six). This achieves the 1 to 3 ratio and will result in all members happily discovering they’ve earned more points. However, it also means you need to adjust the levels and rewards accordingly, which will disrupt what level or benefits members have earned.

It’s far easier to begin with a conservative ratio and make it more generous over time as you know which behaviours you wish to encourage.

If you’re just getting started, you can use the Salesforce system here. Your goal is to find the balance between rewarding quality over quantity – without giving away too many points too quickly.

2 Levels

Points aren’t just a quick feedback system; they’re also often used to assign members to levels. These levels typically confer status and rewards upon members. Levels tend to be important for two groups of members: newcomers and veterans. Newcomers need to be able to progress quickly through the early levels to feel a sense of progress, achievement, and growing influence within the community. Veterans must be able to reach levels other members can’t (without ever getting to the top level).

The best way of thinking about levels is by thinking about the time it might take to progress up each new level. You typically want a newcomer to progress through the first few levels in minutes, the next few in hours, then days, and then weeks. As newcomers become increasingly invested in the community, you want each level to become increasingly difficult to reach. Thus each new level requires exponentially more points to achieve.

We’ve shown an example from one client below:

Level | Points | Level | Points | Level | Points | Level | Points | Level | Points | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | 4 | 11 | 252 | 21 | 816 | 31 | 4160 | 41 | 28,500 | ||||

2 | 11 | 12 | 288 | 22 | 906 | 32 | 5444 | 42 | 38,100 | ||||

3 | 24 | 13 | 324 | 23 | 996 | 33 | 6728 | 43 | 47,700 | ||||

4 | 42 | 14 | 360 | 24 | 1086 | 34 | 8012 | 44 | 57,300 | ||||

5 | 64 | 15 | 396 | 25 | 1176 | 35 | 9262 | 45 | 66,900 | ||||

6 | 88 | 16 | 462 | 26 | 1516 | 36 | 11216 | 46 | 1,05,300 | ||||

7 | 120 | 17 | 528 | 27 | 1856 | 37 | 13136 | 47 | 1,43,700 | ||||

8 | 153 | 18 | 594 | 28 | 2196 | 38 | 15056 | 48 | 1,82,100 | ||||

9 | 184 | 19 | 660 | 29 | 2536 | 39 | 16976 | 49 | 2,20,500 | ||||

10 | 216 | 20 | 726 | 30 | 2876 | 40 | 18900 | 50 | 2,58,900 |

In the early stages, members can progress from one level to the next in 13 days. However, at the intermediate levels (25+ points) it should take a few weeks and, at the advanced stages, it will take 1–3 months. This means that it’s likely to take five years or more to reach the highest levels in this system.

Avoid these levelling mistakes

There are three common mistakes with level systems to avoid:

- Too few levels. It often seems simple and even logical to have just a handful of levels which everyone can understand. You can set them up and maintain them easily. The problem is this causes members to cluster on a single level with the next level seemingly too far out of reach to be worthwhile pursuing. It takes more work to set up more levels, but it’s worth the time.

- Unsustainable naming schemes. Each level needs a name. You might have a naming scheme that begins easy enough. Perhaps Bronze, Silver, Gold, or newbie, regular, top members, veteran. The problem is what happens when members reach the top level. Once you’ve gone to Platinum and Super Platinum it’s not easy to see where to go next. You can switch to animals (mole, giraffe, lion etc.) but you’re still going to end up with the same confusing problem. For simplicity and sustainability, just use numbers (they scale indefinitely!). Or, if you must use names, then use numbers alongside a name (i.e. Expert (25), Expert (26) etc.

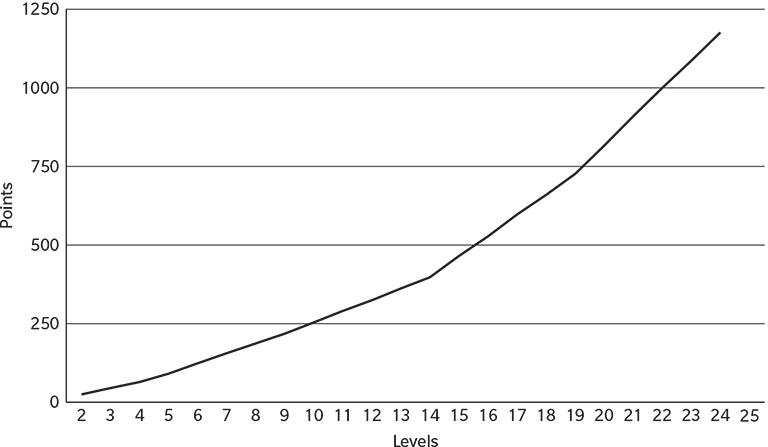

- Exponentially difficult to reach new levels. The third problem is the most complicated to understand, yet also perhaps the most important. It’s called the exponential problem. This problem occurs when you have a curvilinear point to level system. This means the point gap between each new level grows as members progress. So you might need 10 points to move up a level in the early stage, but 100 points to move up the levels in the latter stages. This creates a point curve which looks like the one following page.

Rewarding your members

You can see now it becomes progressively more difficult to reach higher levels as each inflection point in the curve increases the number of points required to reach the next level. At the lower levels you need up to 25 points to progress. By level 20 you need 66 points to progress, which means it should take twice as long.

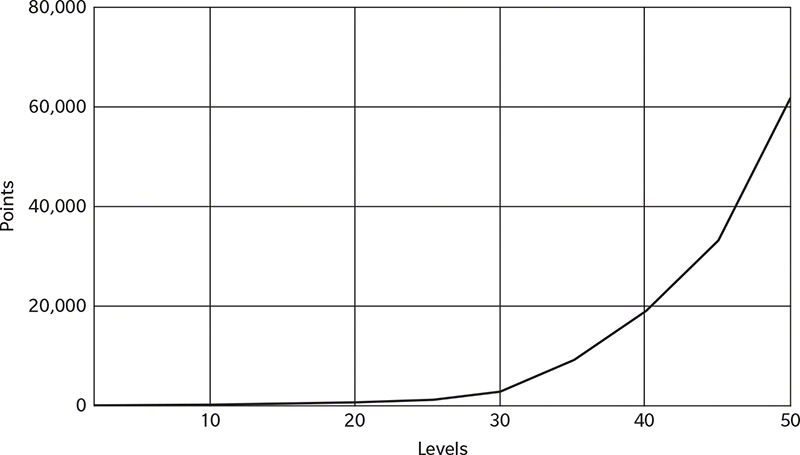

This allows newcomers to gain a rapid sense of progress but doesn’t allow members to reach the highest levels too quickly. However, when you plot our entire point system you can see the curve begins to spike up dramatically using an exponential curve.

To progress from level 30 to 31 you would need 1284 points. But to move from 49 to 50 you would need 5732 points! This is the natural result of an exponential curve which requires progressively more points to reach the next level. The problem is members at the highest levels now have to create thousands of posts or be able to provide hundreds of right answers to move up levels. The gap soon becomes so big it demotivates members from even trying to reach the next level.

This doesn’t mean creating this sort of exponential curve is a bad idea. Video games use a similar system. You do want each new level to become progressively more difficult to reach. The difference between gamification for a community and video games is video games provide you with an opportunity to earn more points as you progress.

For example, the baddies you shoot on level 1 of a video game might be worth 1 point each but on level 10 they are worth 10 points each. Now you can earn 100 points as quickly as you can earn 10 before. This system fails in a community because it doesn’t have an equivalent method to let higher-ranked members earn more points than newcomers. As a general rule, you don’t want to make members wait more than a few months at most to move up a level. Members should always be able to progress up a few levels a year even at the highest levels.

The challenge is to develop ways for members to earn more points as they reach higher levels. And this is where we have to borrow another concept from video games: power ups.

3 Power ups

Power ups are means to enable your top members to earn more points than other members can. For example, as a reward for being a member of the superuser programme, a member might earn 1000 points for every month they remain in the MVP programme. Now you can see how it becomes possible to still progress up levels – even at the highest levels – every few months without having to create thousands of additional posts.

Another option is to assign points for a combination of behaviours. This is often referred to as a ‘mission’ or ‘challenge’. You might create a ‘getting started’ mission requiring members to introduce themselves, update their profile information, ask their first question, follow a few top members, and reply to their first question. If members complete all the tasks within the first week (or month), they earn an additional 500 points.

These sorts of unique challenges are very handy for members who enjoy the gamification aspects of the community – and you can design plenty of them. For example, a member who receives three ‘best answers’ to a question in a given month can earn an additional 500 points. Or members whose combined question views exceed 1000 points receive an additional 100 points per month etc.

You can also award additional points for members who might be nominated as ‘member of the year’ or ‘member of the month’. This helps top members advance rapidly and keep them highly engaged within the community. Likewise, you can manually assign members additional points for remarkable or unique contributions.

In one client’s community, a member shared an incredible story of her cancer journey. Our client recognised that contribution with a ‘remarkable contribution’ badge and a significant number of additional points. This directly rewards quality over quantity – and is almost impossible to cheat. Even the most seasoned members should still feel they can progress to new levels every couple of months.

However, power ups are not always easy to assign within a community. They often require some custom coding and development time to create. But with the right expertise and effort, you can use any activity logged about a member inside of a community to award additional points.

If you’re not able to do this, then don’t use an exponential point system! Stick with something simple without huge jumps and try to add as many levels as you can.

The holy grail of gamification – Universal point systems

The holy grail of gamification, ‘universal points’ (or unified points) is when you can integrate points earned in a community with other schemes (like your customer loyalty and reward programmes). There is just one system which combines points from actions both inside and outside of the community.

For example, you might be able to earn more frequent flyer miles for answering questions in the community or more Sephora loyalty card points (and thus discounts) for community participation. These in turn can give you access to discounts and other benefits. Any online activity which can be tracked and assigned to an individual can also be used to award them points. Instead of having two separate systems, the holy grail is to just have one.

You might also be able to assign points to members for things like the quantity of products or services they’ve purchased from you, how long they have been using those products, how many people they have referred to use your products etc.

This applies to training courses too. As members complete training courses they are assigned additional points in the community. This makes sense, as every training course makes a member smarter and their status in the community should naturally rise as a result. It also acts as a powerful incentive for members to complete more training courses, which might drive more revenue, increase the success of customers, or both.

You can also assign points to members for behaviours which take place offline. For example, if a member attends your conference you can award members points and badges in the community. As long as you have the email addresses of the members who attended your event, you can assign additional points to them.

This isn’t easy to do. It usually requires custom development beyond what is native to any community platform. And once you’ve developed a system, you need to constantly maintain and update it. However, the benefits to the member and the organisation can be remarkable.

4 Roles/permissions

Roles (sometimes known as permissions) are essentially things some members are enabled to do which other versions can’t. A non-technical example would be a hall monitor. Kids who are consistently well behaved in school might be assigned the role of ‘hall monitor’. This is something they are uniquely allowed to do.

You can grant your members a range of technical abilities based upon their past behaviours within the community. As members increase their level, you want to give them more abilities (permissions) within your community. This increases their motivation and enables members to step forward and volunteer support for the community.

A typical approach would be to create a series of permission profiles like those on the following page:

Permissions | |

|---|---|

Visitor (not logged in) | Default system capabilities Can read public content in the community |

Newcomer | Can post three comments per day/comments are pre-moderated. |

Trust level 1 | Can post as often as they like Can send direct messages Can use full HTML in posts and signatures Can change their username Can publish knowledge base articles Can upload images |

Trust level 2 | Can upload file attachments Can mark topics as ‘read only’ Can comment on articles Can access private community areas |

Moderation level | Can delete/remove posts from the community Can suspend members from the community Can create new topics Can close and lock threads Can pin discussions to the top of the community |

Administrator | Can change member permissions Can change the structure of the site Can delete topics Can access the FTP server of the community Can customise and configure every area of the community |

You can clearly see above how each role grants members a set of permissions which enable them to do different things within the community. Once they’ve earned a permission, they can use it to help the community.

WARNING – Even 45% of marriages end in divorce!

Before you begin granting members immense power in your community, remember there’s a high risk that at some point you might fall out with them. If almost half of marriages end in divorce the odds on you falling out with a top member at some point is pretty high.

Permissions can cause harm

Every single permission you grant to members can also be used to harm the community.

Even the most basic permissions, like the ability to post a discussion, can be used to spam the community. This is why you might want to limit the number of new discussions newcomers can create in a community (most spam comes from newcomers). You might also choose to pre-moderate their contributions (approve every post before it’s made public) to prevent spam.

As members have earned higher levels of trust, you might give them the ability to do more things within the community. For example, you might enable them to send direct private messages to other members, change their username, publish long-form articles and use HTML in posts and signatures. Each of these permissions could be abused (I’ve ceased being surprised by how offensive people’s usernames and signatures can be), yet they can also confer a sense of respect and importance upon members.

Finally, at the highest levels, you can provide members with the tools to really help (and potentially harm) the community. You might give members the ability to edit and delete the posts of other members. However, given how powerful this ability is, you should limit this permission to just a core few you really trust. No more than a handful of members should have the ability to perform a moderator role within the community. You should also reserve admin roles solely for employees of the organisation. This is for practical (as well as legal) reasons.

Regardless of how well you know and trust your top community members, you should never equip them with powers which can cause irreparable harm to the community. A member, for example, should never have access to any other member’s private data, access to change the code of the site (FTP server access), or the ability to read a member’s private messages.

It’s not uncommon for a top community member to become upset at a decision or feel they are mistreated and turn rather rapidly to the dark side. In fact, once you start treating a community member like they are in charge, this outcome becomes far more likely.

Tweak your roles

As your community develops, you need to continually tweak these roles to ensure they remain well suited to the community. Roles can be fiddly and tricky to manage. Therefore, unlike levels (where you can have 50 or more), you want to limit permission profiles to just a few. Five is usually fine. Ten is okay if you have a larger community and members are rapidly progressing up to even the highest levels.

Typically each 5th to 10th increase in level also leads to an increase in roles. If you have 50 levels you might have 10 unique permission profiles. However, can you really offer 10 different website permissions to make each jump in role noticeable and worthwhile? The simple answer is no. At least not without going beyond just technical permissions and looking at rewards from a broader perspective.

The full set of rewards

The roles we’ve discussed so far have relied entirely upon technical permissions. These are easy to set in the community and the process then runs itself. But the number of technical permissions you can offer members is limited.

However, technical permissions are just a small part of the total rewards you can offer community members. It’s likely only a handful of members truly care about uploading files, marking topics as accepted solutions, or being able to bypass the standard rules on signature size.

To really create a set of roles which motivate members you also need to consider non-technical rewards for participating in the community. You can do this separately, but it’s better to combine roles and rewards into a single system. We’ve covered many of these in the previous chapter.

You can make a table like the one over the page and highlight the benefits your organisation might be able to offer to members at each role. You can now see how technical permissions are just one part of a bigger reward puzzle and it’s easier to create a ‘bump’ in rewards at every stage of the process.

Note how we’ve kept tangible benefits to a minimum. This helps to reduce cheating and reduce costs. You will also notice that this combines rising technical permissions with more recognition, access, and tangible benefits.

Even if you aren’t using a platform which can grant members extra abilities or you’re simply working with a small group, you can still create a system of a few levels which reward members for their past contributions to a community.

5 Badges

Badges are used in this context to refer to any visual reward you can give to members that symbolises something important. Gold stars in school, for example, are also a type of badge.

If you’ve been using almost any mobile app over the past few years, it’s almost certain you’ve come across badges. They’re used in most new apps which are available today. There’s a simple reason for this; they’re remarkably effective. Numerous studies show badges increase the quantity and quality of user behaviour.20, 21, 22 Better yet, badges don’t just increase the quantity of activity for which the badge was designed; they increase user engagement across multiple activities.23

Badges (just like symbols in the analogue world) are less about the design than what the design represents. Badges work best when they allow members to collect and display their achievements within a community. Badges become a way a member can express their identity and status to other members.

If you’re using an enterprise platform, you can create and award badges to members for performing specific actions. Some, like Salesforce, even allow members to award badges to other members as a ‘thank you’. If you’re using something simple, like a WhatsApp or Slack group, you can either design something physical to send out to members or think of this more like earning ‘gold stars’ in a classroom. You can manually award them to members for great accomplishments and use a publicly viewable spreadsheet or another tool of your choice.

Some platforms enable you to automatically award badges based upon some predetermined behaviour. For example, some communities assign members badges for making their first contribution or posting their first response. Automated badges are typically earned after a member has performed a series of behaviours (i.e. starting 20 discussions might earn a member a ‘conversation starter’ badge – however, on the following page, I advise against this).

You can also use your discretion to award badges to members. You might award a badge to members for making unique, special, or noteworthy contributions in the community. You might not be sure right now what a noteworthy contribution is, but, believe me, you’ll recognise it when a member has gone far above and beyond to create something special. These badges are highly subjective. This makes them both rare and far more impactful.

WARNING – Don’t give badges away too cheaply!

Only award badges for things members are truly proud to have achieved. Many communities have a default setting for badges whereby members are awarded badges for starting conversations, replying to discussions, or other basic activities. Turn these functions off. They give badges away far too cheaply. Badges should reflect things members are genuinely proud about.

As a general rule, if a member wouldn’t be proud to wear the badge at a company conference or community gathering, don’t award members one. Most of us would be slightly embarrassed to walk around wearing a ‘conversation starter’ badge for starting our first conversation. Alas, far too many badge systems do exactly this.

Trust me, members don’t want to receive a badge for asking their first question, they want to get the answer to their question. Forcing members to receive and display an embarrassing badge is counterproductive. Some communities offer a shocking oversupply of badges. I’ve earned five badges on TripAdvisor after posting just two reviews. This undermines the value of all badges.

Good types of badges

There are three ‘good’ types of badges you can award in your community:

- Effort badges. These badges recognise effort. Ideally members identify the badges they want and then make the necessary effort to achieve the badge. This is similar to Scout movements. For example, you might create a badge for members who create detailed guides on a topic of their choosing for the community. When a member creates a guide, they get the badge.

- Status badges. These badges are awarded for a specific achievement, showcase verified expertise, or reflect a series of contributions. These are best delivered subjectively. These are similar to gold stars.

- Hidden badges. These are badges no one knew it was possible to earn until they were assigned to a member for a specific contribution. You might make up a badge and award it to a member to reflect something unique and special they have done in the community.

You can create an infinite number of badges to suit your purposes and serve your needs. This also means you should use badges to help as many members as possible feel they have made unique, useful contributions to the community. A member who created a technical guide about ‘widget x’ can be given a ‘widget x’ expert badge. This is a badge they will be more likely to happily display and a badge which they would internalise.

Badges can also be awarded for participation in certain activities – such as completing training, attending events, being awarded member of the month etc. These all help members feel they have achieved something in the community. And the more that members have achieved (or feel they have achieved) within the community, the more likely they are to continue participating.

Badges shouldn’t reward the same behaviours which points and levels do. Badges should recognise special, unique contributions and achievements. Badges fill the gaps in recognition systems.

If we go back to our example again, we might create a badge system to reward members at beginner, intermediate, and veteran levels. For example:

Audience | Badge | Reason and method |

|---|---|---|

Newcomers | Rising star | A newcomer who has progressed quickly |

Event attendance | Given to members who attend an event | |

Intermediate | Special contribution | Proposed and awarded by Insiders to members who make a special, unique contribution to the community |

Special contribution – Expert in [topic] | For members who have demonstrated a consistent level of expertise in a single topic | |

Expert | Insider badge | Awarded to community Insiders |

Member of the month | Proposed and awarded by the community management team | |

Member of the year [date] | Proposed and awarded by the community management team | |

Remarkable contribution | Proposed by community manager or members and agreed by members | |

Lifetime achievement | For a sustained period of participation in the community |

Not every member will have the time and inclination to make it onto the community leaderboard or reach a high level, but every member should feel like they can make a useful contribution and feel recognised for it.

Step 4: Decide your rewards

Finally we need to be clear about the rewards members earn. These overlap closely with mechanics in many places.

Target audience(s) | Superusers (top community members) | |

Desired behaviour | Answer the majority of questions within 24 hours | |

Persona | Like feeling part of our mission/consider themselves amongst the smartest members in the community | |

Game dynamic | Competition | Achievement |

Game mechanics |

|

|

Rewards | Reputation

| Access

|

In our example above, we’re using competitive and achievement dynamics which we will create as six primary game mechanics. Our rewards clearly relate to each of the dynamics we’re trying to create too. This framework is only targeting top members. We might also create frameworks to reward and encourage newcomers and intermediate members too.

If you’re just getting started (or using an inexpensive platform), keep the system relatively simple for now and test your hunches. You might need to find unique and creative ways of creating the right dynamic and rewarding members. Once you’re starting to see the results of your efforts, you can build a more complex system to build upon your efforts and prevent cheating.

Summary

Even on the simplest of platforms, you have a variety of tools available to encourage and reward members for participating in an online community. The best rewards are intangible. They support the reasons why members began participating in the community in the first place.

You have four broad types of rewards you can offer members. These are reputation, influence, access, and tangible goodies (but try to avoid rewarding members with tangible goods as much as possible). The process of determining when and how to reward members is known as gamification.

Gamification makes participating in the community feel a little bit more like playing a game. Within gamification there are game mechanics like points, levels, and badges etc. and game dynamics like competition, cooperation, and status.

A successful gamification system begins with first determining the dynamics you want to create, then developing a system to amplify those dynamics in the community. You will always be limited by the technology you’re using but you can however still typically design a system to solve your needs.

Be warned that there are unwanted side effects to every game mechanic. So you need to be aware of what these are and design the system to reward quality of effort over quantity of effort. Create a system with an escalating series of rewards in which members can earn more points, levels, roles, and more.

Gamification won’t magically transform a dying community into a hyperactive one. Gamification is better imagined as a scalpel which lets you make precise changes in member behaviour. It can however nurture members to become better contributors and change (and increase) the behaviour of people who are already participating in the community.

Checklist

- Determine what type of behaviours you wish to encourage.

- Use your research to determine what type of dynamic you need to create.

- Review what game mechanics are available to you on your platform.

- Decide how important each behaviour is relative to each other to create a point scheme.

- Create a level scheme. Make sure it’s easy for newcomers to progress in days and then weeks, but veterans to progress to a new level every few months.

- Determine what rewards you can offer and create a series of rewards based upon ranks each member reaches.

- Monitor for cheating and adjust as you go forward.

Tools of the trade

(available from: www.feverbee.com/buildyourcommunity)

- FeverBee’s Gamification Template

Resources

- Yu-Kai Chou – Actionable Gamification: Beyond Points, Badges, and Leaderboards

- Apple’s Support Community – Gamification System

- Joel Spolsky – ‘A Dusting of Gamification’ (https://www.joelonsoftware.com/2018/04/13/gamification/)

- Sebastian Deterding – ‘Meaningful Play: Getting Gamification Right’ (https://www.slideshare.net/dings/meaningful-play-getting-gamification-right)

- Salesforce’s Trailblazer Ranks (https://trailhead.salesforce.com/en/trailblazer-ranks)