chapter 9

Overcoming problems

Launching a community is like releasing a clowder of cats into your living room (yes, that’s what a group of cats is called). It might seem fun, but it’s probably going to cause a lot of stress, affect your reputation, and have some interesting legal ramifications.

In the business world, these unintended consequences are known as risk factors. And if you’re not prepared for them, they can sink your community before it even has a chance to swim. Worse still, a failure to consider the risks can result in irreparable harm to your members, yourself, and your organisation.

Even if you’re launching a community for a personal hobby, or a WhatsApp group for a local club or some friends, many of these risks will still apply. You should be aware of your responsibilities. So, don’t skip this chapter!

We’ve encountered some of these risk factors already. Members might say or do something that puts you and your organisation in a legal jam or potentially cause a PR disaster. In this chapter, I’m going to go beyond just moderation issues and identify the biggest risks you’re likely to face and how to mitigate each of them.

Where will the hits come from?

As Mike Tyson once said,

‘Everyone has a plan until they get hit’.1

Managing a community at times can feel like being in the boxing ring. You’re going to face dangers and get hit from some unexpected places. Some of these hits you can see coming and duck. Others are unavoidable, but you need to prepare a good defence.

I’m often stunned by how poorly prepared community leaders are for something going wrong. Many of the strategies I’ve reviewed over the past decade don’t even consider the risk that something will go wrong. They simply assume everything will proceed without any problems. I don’t know about you, but I want to be prepared for every possible problem my community faces. When something bad happens, I want to tell my boss: ‘Yup, I thought that might happen ... this is the plan to deal with it.’

As the famous adage goes: ‘If you fail to prepare, you are preparing to fail.’2

The knock-out blow

An acquaintance of mine used to run a community for a large American bank. For years she had been steadily building support from her colleagues and growing participation within the community. Then, one morning, she was called into her boss’ office and given the bad news. The community had become too active and they had decided to close it.

The problem, as they explained, was compliance.

Banks must abide by strict regulations. Her bank knew from the beginning that a community was risky. Members might share bad advice with one another. However, when it was small they weren’t too worried. But as the community grew bigger, so did the risk. The bank therefore decided to shut the community down; it had become too successful!

The five types of risk

You might be thinking risk is just your lawyer’s problem. And you would be wrong ... very, very, wrong! You can’t shift the risk of a community to a lawyer because (a) lawyers might not even know the full legal risks and (b) most risks aren’t legal risks. Risks are your problem and you need to take steps to address them.

Before we can mitigate the risks, we need to identify them. We can separate risks into five key categories. These are shown in the table below:

Type of risk | Description |

|---|---|

Legal | This covers every potential legal implication of launching a new community. The inherent risks here are vast, confusing, and change by sector and country (and sometimes individual states within each country). If you’re launching a community in sectors like healthcare, finance, or involving minors you need to be especially careful with your legal responsibilities. |

Reputation | This covers everything which could harm an organisation’s reputation amongst its stakeholders (customers, employees, shareholders etc.). These risks include losing credibility with customers, losing the passion of top customers, generating negative publicity, upsetting employees, and harming (or undermining) marketing campaigns. |

Risk to members | This covers all potential harm which can come to members as a result of visiting and participating in your community. If you’re launching a community you have both a moral and potentially legal duty to take reasonable steps to ensure members don’t come to unnecessary harm. |

Risk to staff | Launching a community can potentially pose a risk to staff – especially staff managing the community. Staff who enforce the rules can also become the targets for personal abuse or unwanted solicitations. Likewise, a community may turn its wrath towards visible staff members when they feel disgruntled with the company. |

Failure | This covers the risk of the community failing to gain traction, losing support, and when things simply don’t work out the way you planned. This is a miscellaneous category for risks which don’t fall into any of the categories above. |

Let’s identify the biggest risks in each category and outline the steps you can take for overcoming or mitigating each risk.

Legal risks

In the decade I’ve been consulting, I’m still staggered by the vast number of legal issues which can arise. These issues will likely multiply in the coming years as concerns over online privacy increase and liability for the consequences of online community behaviour remains a topic of considerable public concern.3

However, while the breadth of legal risks is vast, there are some that crop up more often than others. Before I begin, let me state clearly and unequivocally, I’m not qualified to provide legal advice. Make sure you consult with a lawyer before implementing or addressing any of the suggestions below. Be aware that the law often changes by country (and even by state).

Could your superusers be considered employees?

In 2011, AOL settled a lawsuit with former moderators of its chat rooms for $15m. This lawsuit emerged when a group of moderators claimed their volunteer work at AOL crossed the threshold to be considered employment.4 Although these moderators agreed this was a volunteer position at the time, this didn’t protect AOL from the lawsuit. Other groups, including contributors to Huffington Post (also now owned by AOL), have also tried to claim compensation for their contributions to a community with varying levels of success.

If you’re running a programme to encourage and support top members, you need to be careful your superusers aren’t undertaking tasks which could reasonably be considered employment. There is no definitive line here (and the law varies greatly by country on this one) but there are several areas according to my (UK-based) solicitors to be aware of.

As a good rule of thumb, the more you treat superusers the way you might treat employees, the more likely they could be deemed employees in the eyes of the law. The most common dangers include (in order of importance):

- Replacing the work of employees. If superusers are performing the work which was previously performed by employees, this can be considered employment. This is most likely to be a problem if paid staff are made redundant in favour of community volunteers. For example, in 2018 reports emerged Microsoft had laid off its Xbox support team in favour of unpaid volunteers.5 This would appear to present a clear legal risk to Microsoft. However, Microsoft may have avoided the risk due to a small technicality. One commenter has claimed Microsoft hadn’t technically fired paid staff but instead simply not renewed the contracts of contractors.6

- Instructed what to work on (and when). AOL’s volunteer moderators famously had to work at fixed times and digitally punch in and out. This clearly closely resembled employment. If you are directing and strictly monitoring the work of volunteers, this raises the risk they may be considered employees.

- Receiving rewards. If superusers are rewarded with things which have tangible value, this can be considered payment for their work (and likely payment that’s below minimum wage in many regions – leading to further legal problems). For example, AOL provided moderators with free internet access. This had a clear equivalent financial value.

- Firing volunteers. Firing volunteers for not working hard enough starts to resemble an employee relationship rather than that of a passionate volunteer.

- Receiving training. If your volunteers must complete a training course before being allowed to volunteer, this also starts to resemble an employment relationship.

- Signing contracts. Demanding volunteers sign contracts (most commonly NDAs) can seem logical, but also raises the question of why a contract is required if someone is just a volunteer.

WARNING – Volunteer agreements alone won’t protect you!

Some communities attempt to resolve this legal quandary by requiring members to sign a statement agreeing that their contributions are voluntary and there is no expectation of reward.

However, just because members have agreed they’re not entitled to compensation doesn’t mean that courts will. This is like paying employees below minimum wage because they agreed to the contract. It might be possible (although certainly not ethical) to do it, but it still breaks the law.

You can find plenty of organisations running ‘unpaid internships’ who fell afoul of the law even though the interns agreed to the terms when they took the internship. Is your superuser programme really that different?

In many parts of the world (notably the USA), for-profit companies are legally prevented from accepting volunteer labour.7 This puts community professionals in an interesting jam. Almost everyone replying to a discussion is technically a volunteer. However, there is a clear difference between someone voluntarily deciding to help out or promoting you on their own accord and running a large-scale volunteer programme in which you direct, coordinate, and reward the work of volunteers. You may wish to spend some time researching the Fair Labor Standards Act.8

Sometimes relatively small tweaks (such as providing volunteers with the freedom to work on areas that interest them instead of directing their work) can keep you on the right side of the law.

Are you risking your members’ data and privacy?

One of my clients used to have a community of four million members. Today, they have a community of one million members.

I swear this wasn’t the result of my poor advice! Instead, it was on the advice of their legal team. When the EU introduced GDPR laws on data privacy, they were advised to remove the accounts of anyone who hadn’t visited the community within the past year (after a warning to members). This resulted in the removal of 80% of their members.

Interestingly, another client looked at the same regulations and simply anonymised the contributions of millions of members who didn’t opt in to their new terms and conditions.

These examples highlight the challenge of new laws on privacy and the different ways companies interpret these laws. For example, I had one client who read the GDPR laws and spent several hundred thousand dollars moving their community to a USA-based provider. Another client looked at the same laws and decided it wasn’t necessary.

Drastic steps like these are becoming altogether more common as companies adopt varying interpretations of new data privacy laws being introduced around the world. Mature communities with millions of posts from hundreds of thousands of members are increasingly being forced to make painful decisions to comply with the law.

Don’t worry, I’m not about to bore you with the intricacies of data privacy and security laws. That’s partly because I’m not qualified to do so and partly because it would take too much time. However, again, make sure you get qualified legal advice here. Given the importance of data privacy and security on the public agenda, there are some major things to consider. These are:

- How much data do you collect about members? In the beforetime of community building, community leaders often endeavoured to collect as much data about members as possible. After all, it was free to collect and some of it was sometimes useful. You might use this data to notice interesting demographic trends or determine the kind of activities and events that might be hosted. Up until just a couple of years ago, data was considered a valuable asset and you wanted as much of it as possible.

Today, data is better seen as a costly liability. The more data you collect about members, the greater the risk of a data breach and the more severe the consequences of that breach. Most community leaders have shifted from trying to collect as much data about members as possible to trying to collect as little as needed. For example, if you don’t need your members’ real names, age, biographies, gender, and location, don’t collect it. Often just a username and password will suffice. - Have a plan for removing data you don’t need. Sit with your legal team and get definitive answers to questions such as how long you should keep members’ data for – especially if they haven’t visited your community in years. Develop a plan for removing a member’s data from the community if a member requests it (or if you are legally compelled to do so). If you’re using one of the bigger platform vendors, this should be relatively easy to do. On smaller platforms, this might involve some manual effort and cause other challenges (see box).

- Decide whether to block access to any regions. Data privacy laws differ by region. One client of ours, The Truth Initiative – an organisation dedicated to helping US citizens fight tobacco addiction – felt it was easier to block all visitors from countries within the EU than comply with the EU’s GDPR laws on data privacy and security. This made sense; they were a USA-based organisation targeting only people in the USA.

WARNING – Removing data causes problems!

You can’t simply remove a member’s data from a community without causing problems. Removing a popular member, for example, might also delete thousands of discussions they’ve created or responses they’ve given. This would hurt your search traffic and make some older, popular conversations almost impossible to follow. And don’t forget removing so many discussions might affect the points members have earned for answering those questions – which in turn might affect their privileges within the community.

Most communities tackle this problem by anonymising the contributions of members who asked for their data to be removed.

You might be forced to make similar decisions in the future. Even if you’re not based within a country, you might still be subject to its laws if citizens from those countries are visiting. In the past we’ve had to make some tough judgement calls on visitors from various parts of the world.

Who owns ideas?

In 2014, I worked with a client on a community strategy which included ideation – i.e. members being able to submit and vote on ideas. Several of those ideas were adopted and one even became a primary feature of the new software product they were releasing. We were so proud of this success we even persuaded the CEO to name-check the community member who suggested the idea on stage. This backfired in a way we should’ve seen coming.

Instead of feeling proud to be mentioned, this member consulted a lawyer and decided he was entitled not only to the credit for the idea but also a percentage of the royalties generated from the new software product. The member eventually settled for a relatively low five-figure sum. And, despite its success, the company insisted the ideation feature be removed shortly after.

Getting product ideas from members sounds like a remarkable win for everyone. Members get to feel they are helping create the exact products they want and the company gets a list of ideas they can use to create their products. But you need to carefully peruse through the terms and conditions with a lawyer. The probability of this happening to you is low, but not so low you can ignore it.

Do members share and discuss illegal or illicit content?

Managing a community would be a whole lot easier if your members would simply stop unintentionally (and intentionally) sharing illegal or illicit content.

The most common example is copyright content – either images or videos. For example, a member might share a YouTube video featuring copyright music or movie scenes. While the person who edited and uploaded footage without permission is in the wrong – when it’s shared in your community by other members it can still be a social and (in some countries) a legal problem.

This also extends to other forms of media. Members might cut and paste articles without attribution, share PDF versions of relevant books for which they do not own the copyright, and post recordings or audio clips which might support their point but are illegal to share within the community. Even stealing someone’s photos and posting them in your community is a problem.

Part of the problem is your members are either unaware or ambivalent about copyright laws. If you’ve ever seen a YouTube video where the creator adds a note ‘I do not own the copyright to this material’ (essentially confessing their crime), you can appreciate the level of legal expertise amongst some of your community members.

The impact of most infringements is mild and many countries have reasonable laws in place which prevent the host of a community being responsible for the activities of its members – so long as they react quickly to remove such content when notified. However, it’s still worth addressing such issues with a lawyer and developing a process for victims of copyright theft to flag potential copyright content. You should then check if the accusation is valid and quickly remove it. You might also, for example, want to check if sharing memes and gifs is ok within the community.

A more serious problem is when members share clearly illicit content – typically pornography or violent material. This is most common in communities dominated by men and, in the most serious cases, can result in your community being removed by your platform vendor. Facebook is notorious for removing Facebook groups that violate its terms and conditions without warning. Often this kind of content is either automatically flagged by the technology platform (and removed) or identified quickly by members or moderators and deleted – along with the member who posted it.

An even more pernicious problem is when sharing of this nature takes place in private messages and groups between members rather than in public. This is harder to track and stop. Private messages are, by their nature, private. You shouldn’t be reading them without a clear complaint from a member. Yet, you can’t ignore this potential problem.

I was shocked when one client, overwhelmed by the volume of illicit content being shared in his community, proposed creating a passworded place for bad content that was outside the reach of search engines.

Turning a blind eye to the problem is never the solution! It simply hides the problem until it becomes so big it can’t be ignored. If you can’t afford to automatically detect this kind of content sharing, at least be hypervigilant in noticing possible examples of it and offering rewards to members for reporting illicit content they see shared within the community so you can quickly remove it.

Is your competition actually gambling?

In a previous role, I wanted to host a competition for members of our community. The prize was a free trip to the company’s headquarters. On paper, this sounded simple enough. Organisations do this all the time and it didn’t seem too technically difficult to run.

I couldn’t have been more wrong.

While competitions can be an interesting and unique way to encourage participation, they can also run headlong into a wide range of legal problems. For example, a competition will typically fall into one of three buckets:

- A sweepstake. Where a prize is based upon random luck of the draw.

- A contest. Where the prize is based upon skill and effort.

- A lottery. Where people have to make a purchase to be in with a chance to win.

Each bucket represents very different legal obligations.

Even the type and size of the prize are important. If the prize has a conceivable cash value then it too may be subject to certain regulations (and taxes).

Also consider your own liability. If the prize is a free trip to visit your headquarters, are you prepared for someone from China to win the prize? Are you prepared to sponsor their visa, provide medical insurance, and take reasonable steps to ensure they come to no harm? What if someone from a less developed country wins, you sponsor their visa, and then they disappear after they arrive? Do you really want to wade into that legal quagmire?

The obvious solution is one taken by most hosts of competitions: limit participation just to select areas (typically just the country where the organisation is based). Yet if you limit the prize to just participants in your home country, are you prepared for the backlash from other members who wish to participate?

Also be careful how you select the winner. Is there a clear criteria you can use to determine the winner or are you subjectively making a decision?

Likewise, if you’re claiming the winner will be drawn at random, you can’t simply look at a list of names and pick one. That’s not random. You need a defensive system for a random selection

Competitions can be fun and engaging for members, but be cautious about how you structure and implement them. If you aren’t careful about the structure and terms of your competition, you might be accused of facilitating gambling. If you fail to consider the type of prize, you might find yourself saddled with enormous costs (or a member uprising).

Are you taking sufficient steps to protect minors?

In 2019, ByteDance (founders of the popular TikTok app), and YouTube (owned by Alphabet) were fined $5.7m and $170m respectively by the FTC (Federal Trade Commission) for failing to comply with COPPA (the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act).

COPPA is a United States federal law which aims to protect children in online environments. It applies to all organisations which are targeting children under 13 years of age and collects the data of minors.

You’re probably not targeting minors to join your community. However, it’s important you check with a lawyer and ensure you do have specific policies in place which forbid minors from joining your community and processes to prevent them from joining your community. Some organisations, such as Microsoft, have been known to require a tiny online payment for those who wish to participate. This ensures a parent is aware of their activities.

If you are encouraging (or accepting) minors as members, the broad principles of compliance include having a clear privacy policy, making a reasonable effort to provide direct notice to parents of operating practices, and obtaining parental content on any collection and disclosure of child data.

The USA is just one of many countries to enact laws to protect minors in online environments. Other countries and territories have similar laws. For example, Europe’s GDPR implemented broadly similar rules for its 27 members. These have provisions for parental consent, tracking technologies, and privacy policy rules.

WARNING – Don’t copy terms and conditions!

If you find yourself copying another organisation’s privacy policy or terms and conditions, you should stop everything you’re doing and find yourself a lawyer instead. The risks to you and to most organisations are far too high to do this on the cheap.

This doesn’t mean you shouldn’t review other terms and conditions, this is good practice to identify potential issues you haven’t considered, but don’t simply just copy them.

As a general rule, if you can’t afford a lawyer, you can’t afford a community.

Reputation risk

When you launch a community, you’re also likely to incur a risk to your reputation (or your organisation’s reputation). When you launch a community, you give every possible ‘enemy’ (disgruntled customer, fired staff member, or competitor) a channel to attack you in front of your biggest supporters, allies, and friends. Your community is a place where any misstep you or your organisation makes can be highlighted and amplified across the web.

Sadly, you can’t (easily) prevent members from doing or saying bad things within the community, but you can plan to significantly reduce the reputational damage when it happens. In my experience, the most common risks include the following.

Bad publicity

For many organisations, the biggest risk lies not in upsetting members but in the bad publicity which can result from messages being shared elsewhere. In October 2019, messages from WeWork’s private community for staff was leaked to The Guardian, who ran a negative story about the company at a sensitive time.9

Fortunately, most journalists are too busy fighting off your PR team to browse through your community looking for dirt. But any mischievous actor can initiate and feed journalists posts about members complaining about anything in your community.

If you don’t think stories like ‘Top customers turn on (your brand) over (issue)’ are newsworthy, you haven’t been in the industry for long enough. Even the smallest of community efforts should be cautious. A growing number of negative media stories highlight private group WhatsApp messages in their stories. It only takes one disgruntled member to share screenshots to cause real damage. Just because you’re using a private platform, doesn’t mean you’re safe from any reputational harm for what happens in the community.

Beyond the obvious ethical reasons, this is also why posts which are (or could reasonably be considered) racist, sexist, transphobic, or otherwise mean and hateful should be removed quickly. It only takes a very small number of posts before (you/your company) has a (sexism) problem.

Once these kinds of stories take hold, it’s very hard to shake off this reputational damage. Reddit, for example, is still (gradually) cleaning up its image for decisions taken almost a decade ago. In an age where people increasingly buy products and support organisations which align with their values, a small number of offensive community posts can be crippling.

Angry customers

One of my favourite moments in every consultancy project is when someone in marketing (and it typically is marketing, sorry folks!) suddenly realises that their beloved audience might say something mean about them in the community. This is followed by a seemingly reasonable request of let’s approve all posts before they appear in our community.

My response to this is usually the same:

Customers are going to say bad things whether you launch a community or not. And if they’re going to do it, we want them to do it in our community. We can provide a response, give them support, and turn them into loyal advocates.

I’ve lost track of the number of times a disgruntled customer has turned into an enthusiastic supporter after having a terrific, empathetic experience with the community team. Instead of trying to stop members from highlighting their frustrations in the community, you should be encouraging them to do it. Every complaint provides an incredible opportunity to keep a customer and address the concerns that they (and others) might have. Usually, the problem isn’t members voicing complaints, it’s when you’re not able to do anything about the complaints.

In a perfect world, the organisation would acknowledge and respond to every complaint with a kind, friendly tone and resolve the issue speedily. The reality is often a lot more complex.

Sometimes the organisation isn’t able to respond for legal reasons. For example, the organisation might not want the community manager providing advice on matters of the law. Other times the organisation can’t respond because they don’t want to reveal some confidential information about the member or themselves. For example, a company might not be able to respond to a complaint about a product that’s being quietly tested amongst a handful of customers. Occasionally, the problem is simply not one which can be resolved.

In these situations, it’s worthwhile putting together a list of issues the community team might not be able to resolve and sharing them within the community. This provides members with at least a minimum level of information to understand why they’re not receiving the response they might want.

Should you remove criticism and negative reviews?

In early 2020, I was looking to buy a lightweight tent. I visited two communities from distributors to see what customers were saying about different brands. One community was filled with positive comments about their products. The other had both the good and the typical mixture of bad comments.

Out of curiosity, I sent an email to the community manager at the former to find out why there were no negative posts (not a single complaint) about their products in the community.

He gave me a remarkably honest answer:

‘If people post a criticism about our products we try to contact them directly and remove the negative post from the community.’

At first, you can see why this sounds smart. You don’t want potential customers like me seeing negative posts about your products. It might cost your business! But this approach is already incredibly short-sighted. The community which featured only positive posts didn’t feel authentic. Imagine an influencer who only posts positive reviews. After a while you would become suspicious. People need to see the good and the bad reviews to make decisions.

Without negative posts and reviews, people trust positive posts less. This means you can’t remove the negative comments without also removing the authenticity of the community.

Disappointed members

Customer complaints are just one reason why members get angry. You might not have much control over that. You do have a lot more control when members are critical of the community experience.

Community members are often the most passionate about the topic. For brands, they’re often the organisation’s best customers or most loyal supporters. They expect a high level of support from you in a community. If you fail to respond quickly to their concerns, acknowledge their contributions, and solicit their feedback in decisions, they will quickly turn against you. Worse yet, you’ve given them the very tool they can use to organise their efforts against you.

I’ve seen disgruntled members start advocating for competitor brands within the organisation’s own community. If you can’t provide a high level of support to members, small grumbles can quickly escalate into devastating collective action.

Another problem is unintentional leaks of confidential information. For example, someone might reveal information about an upcoming product which was supposed to be announced at an upcoming conference. As we’ve seen, it’s fairly common for posts in a community (even a private community) to find their way into more mainstream media.

The best approach to preventing accidental leaks of information is training. Every staff member who participates in your community should receive training, which encourages them to participate and equips them with the guardrails to do it well and without problems. And while you can’t prevent disgruntled former staff members from sharing private information, you can stay vigilant on posts from newcomers to quickly remove confidential information.

Risk to members

Regardless of what the law in your jurisdiction says, you have a moral duty of care to the people who have decided to participate in your community. This means you need to identify and mitigate most of the risk they face. These risks come in three forms: harassment conflicts between members and spreading false information.

1 Harassment

If you’re managing a community, you need a clear policy in place which both forbids sexual advances and provides all members of your community with a simple mechanism to report cases of harassment and unwanted attention by other members. This should be shown within the contact form and included in your welcome and onboarding information.

When you do receive a report of harassment, you should take it seriously and you may wish to remove the perpetrator from the community (or advise the accused member to cease any further contact with the recipient). If the perpetrator does not abide by this instruction, you should remove the member immediately.

If you’re looking for help with your code of conduct, look at events like CMX (a summit for community managers), which has excellent policies in place for dealing with harassment. You can adapt most of this to an online community too.10

2 Conflicts between members

In any group of people, you’re going to experience minor personality disagreements. However, if these aren’t dealt with they can escalate into serious conflict.

In December 2017, two gamers ‘swatted’ another gamer after a heated argument over a $1.50 bet. Swatting is the act of calling in a fake crime report to someone’s address, which will merit the response of a SWAT team. In a tragic twist of fate, the perpetrators gave the police the wrong address and the SWAT team shot and killed an innocent stranger.11

Thankfully swatting is rare outside of communities targeted at young male audiences. A more common problem is ‘doxing’. Doxing is the act of researching and publishing someone’s private information (typically address or phone number) online. Any act of swatting or doxing should result in the immediate removal of the member and a community-wide warning that such behaviour is not tolerated.

However, it is also useful to pre-emptively try to prevent such situations by addressing conflicts before they step beyond the realm of genuine topical debate and into personal insults. Often a simple knock it off now style email (along with locking the discussion so others can’t participate) can resolve the issue.

3 Spreading false information

In many industries, the challenge isn’t persuading members to share information, but getting members to share good, accurate information. In sectors such as healthcare and banking, organisations are prohibited from sharing information which is false and can lead to harm. Even hosting such content can cause problems.

As mentioned, while many countries have laws (such as Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act) which generally protect communities as long as they abide by specific conditions, there are several exceptions in the applications in these rules which could make you responsible for any information published which causes members harm. You should research and be aware of these exceptions.

You should also consider the ramifications to members if false information is shared within the community. There are levels to false (or bad) information which range from life threatening to mild annoyances. However, bad community advice which ends up ruining a member’s favourite shirt in the wash is very different from advice which results in a member getting a terrible mortgage deal, going bankrupt, or destroying a close personal relationship.

Most of the time false information causes great annoyance rather than election-changing outcomes. In one of my earliest gaming communities, one member suggested you could improve gaming performance by overclocking the monitor (essentially making it refresh the screen faster than it was designed to). About a dozen members blew up their computer monitors following this advice.

Just because you have no legal liability for these outcomes doesn’t mean you have no moral liability for protecting members to the best of your abilities. You should endeavour to warn members about the risk of following unverified advice and quickly clear bad information.

Are you the arbiter of truth?

The problem with removing false information is you immediately position yourself as the arbiter of truth within the community. That might sound fun, but do you really want to get sucked into endless semantic debates about what is and isn’t true?

In most cases, the consensus of the community performs this role – you would do better to rely upon the outcome of passionate (and informed) debates while pruning statements which can’t be sourced and could do harm.

An even better approach is to identify ‘risky’ topics and either pre-approve these responses or check them for accuracy. Wikipedia follows this approach in its community. There are plenty of articles only members with a good reputation are allowed to edit. You can do the same with any topics which may significantly affect your members’ health, wealth, or relationships.

Risk to staff

In most communities, activity can happen at any hour of the day. Members are demanding and want answers quickly. You (and potentially your team) are the focal point for your community – especially disgruntled members. This creates two acute risks to the community team (i.e. you) in managing the community. The first is ‘burn out’ or mental health problems caused by the nature of managing an online community. The second is the risk of being targeted by vengeful members of the community.

Larger communities typically have a paid moderation team to provide quick responses 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. However in smaller communities there isn’t the need, nor the budget, for moderation teams. Instead community managers are implicitly expected to keep an eye on the community over the evenings and weekends to ensure nothing blows up.

If you agree to this implicit understanding, you will never be able to relax. This is like being told you can go on vacation, but every three hours you need to push a button or some terrible unspecified harm might happen (fans of the TV show Lost might rejoice). Sure, it doesn’t take long to check the community, but it’s psychologically damaging.

Worse yet, you’re probably not going to just skim the community for problems. While you’re there you might as well check your emails, respond to other questions, and see if anyone else needs help. It’s not surprising that the topics of burnout and self-care are some of the most frequently discussed topics in community management today.12

The solution here is a healthy dose of realism. Very few problems are show-stoppers – especially in small- to mid-level communities. Sure, it is theoretically possible that someone might post a problem in your community so serious that it needs urgent attention before it becomes a major threat to the company (or the member). This is especially true in larger online communities where members have been known to post threats of violence to themselves or others. Swift action in these communities can quite literally save lives.

But, as tragic as these situations are, they are incredibly rare and I can’t remember any community manager outside of a one million plus member site who has ever had to deal with it. Few (if any) community leaders can seriously claim to have prevented a crisis – despite checking their community every few hours. The largest communities have a moral obligation to hire paid moderation teams specifically for these challenges.

It’s not likely that the community will implode because you’re not checking it every few hours. It is, however, extremely likely that checking the community every few hours will harm your mental health and leave you unable to support the community at the level it needs. Give yourself and the community a break outside of working hours. Very few things can’t wait until the morning to be dealt with.

The second type of problem is harassment and personal attacks from community members. This is sadly as common as experiencing burnout and often more consequential.

The bad apples in the big forest

In February 2020, author Tim Ferriss warned of the dangers of having a large audience by comparing them to the size of cities:

‘Let’s assume you only have 100 or 1000 followers. You should still wonder: At any given time, how many of these people might go off of their meds? And how many of the remaining folks will simply wake up on the wrong side of the bed today, feeling the need to lash out at someone? The answer will never be zero.’13

Once you get to an audience the size of small cities, the number of problematic members begins to rise sharply. An audience of 20–30 isn’t likely to present a major problem. Most people can deal with this quite comfortably. But once the community reaches hundreds of thousands of people – even millions – there is more than likely to be a few troubled members amongst them.

The problems Tim lists in his post are very similar to the problems any gathering of community managers would quickly name. They include stalkers, death threats, harassment, desperate pleas for help, friends with ulterior motives, and increased spam and phishing attempts.

Managing a community makes you a very visible persona amongst a large group of people. It’s often not difficult for someone to track down your name (even if your full name isn’t displayed). Once someone has your name they can find your social media profiles. Once they have those profiles, they can often track down your hometown, friends, spouse, and possibly even your address.

One community manager I know had her face photoshopped into pornographic images, which were sent to her Facebook friends. Others have had their email, social media, and personal website accounts hacked.

It’s sadly common for women managing communities to receive unwanted advances and comments from members of the community. Sometimes these are members ‘just reaching out’ to community managers through external channels such as LinkedIn and Facebook. Other times comments in the community focus on the community manager’s looks or personality.

I strongly recommend all community leaders to consider these risks and take reasonable steps to protect themselves, set appropriate boundaries, and ensure private information remains private. This might include:

- Don’t use your full name or photo. In many communities, the community team either use their first name or a pseudonym to prevent personal abuse. This isn’t always possible (or acceptable in some professional communities). However, it is a useful barrier to maintain a reasonable level of privacy.

- Only engage in the community. Do not accept requests from members to become friends on Facebook and Twitter unless you have spent time with them in person and know them well. If members attempt to contact you outside of the community, write them a message to let them know it’s best to befriend each other on your community platform instead. If you need to connect with members on WhatsApp or Facebook for work, create a separate work account for these connections and consider using a second phone for work.

- Turn the privacy setting up to full on your social media profiles. This is easier for Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram than it is for LinkedIn. You may wish to reconsider whether you want to list your current place of employment on LinkedIn. Be aware that if you use the same username or images on one account for any other – people can track you down through a Google Reverse Image Search. If you don’t want members researching things like your eBay buying history – use a completely different username and photo.

- Never reveal location information via social media profiles. If your social media is not private, it’s best never to reveal location information via social media. Once people know the area you live in, it becomes a lot easier to track down your address. It’s also wise to avoid broadcasting when you and/or your partner are away from home (especially at company or community events).

- Use anonymous domain registrars. If you have personal websites linked to your name, use an anonymous domain registrar to hide your address. Anyone can ‘whois’ a website url to reveal the information of people who created the site.

- Use two-factor authentication on all email and social media accounts. Ensure you use two-factor authentication on all your accounts. This makes it far more difficult for people to hack your accounts. For even better security, use an authentication tool (like Google Authenticator) rather than SMS message as your choice of authentication.

This won’t deter every possible problem you might encounter. However, it should limit the frequency and severity of the problems you encounter. If you’re building a community for an organisation, you should always insist on creating or seeing the internal policy for reporting situations where you don’t feel comfortable.

Like most of the risks here, these types of incidents are thankfully rare. Yet they are common enough that you should take measures to prevent and mitigate them.

Execution failure (and benchmarks)

The final kind of risk is probably the one that we fear the most: failing to attract people to our community. This is like hosting a house party and no one showing up, only it’s a lot more costly. This isn’t an irrational fear either. It happens all the time. It’s also a reality too few community leaders properly plan for (and subsequently overcome).

If you find yourself struggling to attract enough members, you might get tempted to dream up an exciting batch of ideas to boost engagement. Try to resist that temptation. None of these ideas is likely to work (at least over the long term). Before you can find the right solution you have to know what the problem is.

Your data can really help you here. For example, you might be able to see every action a newcomer takes and identify precisely where you’re losing them. However, this raises a new problem. What’s good or bad when it comes to metrics? If you can see half of your newcomers are still participating after three months, should you feel bad that you lost half of your audience or should you feel great that you kept half of them active?14

We need some benchmarks to help answer these questions. My consultancy, FeverBee, has gathered millions of data points from thousands of communities of all shapes and sizes. After segmenting these into a few key categories, we were able to identify (with a 95% confidence interval) a range of benchmarks below:15

Size of community (reg. members) | % of email subscribers who click links in emails | % of visitors who register | % of registrants who make a contribution | % of contributors who remain active after three months |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Ex-small (0 to 1k) | 2.62%16 | 10%–51% | 22%–48% | 17%–45% |

Small (1k to 10k) | 2.62% | 4%–12% | 14%–24% | 16%–21% |

Medium (10k to 100k) | 2.62% | 2%–8% | 4%–19% | 16%–20% |

Large (100k to 1m) | 2.62% | 0.3%–3% | 1%–11% | 12%–17% |

Ex-large (1m+) | 2.62% | 0.1%–2% | 0.1%–5% | 12%–15% |

A quick word of caution here. This data doesn’t cover every type of community. We have little to no data on platforms like Slack, WhatsApp, and Facebook groups. The rate could easily be a lot higher or lower. We also have little data for private communities like paid-membership communities, employee communities, and those you might hang out in just with your friends (I expect the conversion rates will be higher, but I don’t know how much higher).

However, you should be able to use these to begin diagnosing potential problems in your community and find a solution.

WARNING – Conversion rates naturally decline as a community grows!

When a community is launched, it tends to attract the people who know you best and those most interested in the topic. By nature, these are the most engaged types of people. As the community grows, those less interested in the topic tend to drift in. This causes a natural decline in most conversion metrics. You can see the conversion ratios shrink as the community grows.

This could be more important than you imagine. For example, imagine you’re given targets to hit by your boss. You don’t want to be held accountable for metrics which naturally decline as a community grows. If you are looking for conversion metrics to hit, try to aim for the upper range of the metrics above by the size of your community.

There are a few common problems you’re likely to face. Here is how you diagnose and overcome each of them.

1 Failure to gain traction

It’s not easy to get enough members to form a habit of visiting and actively participating in the community. The advice in this book should help, but it’s not bullet proof. There are plenty of reasons why the community might not spark to life and you need a plan for dealing with them.

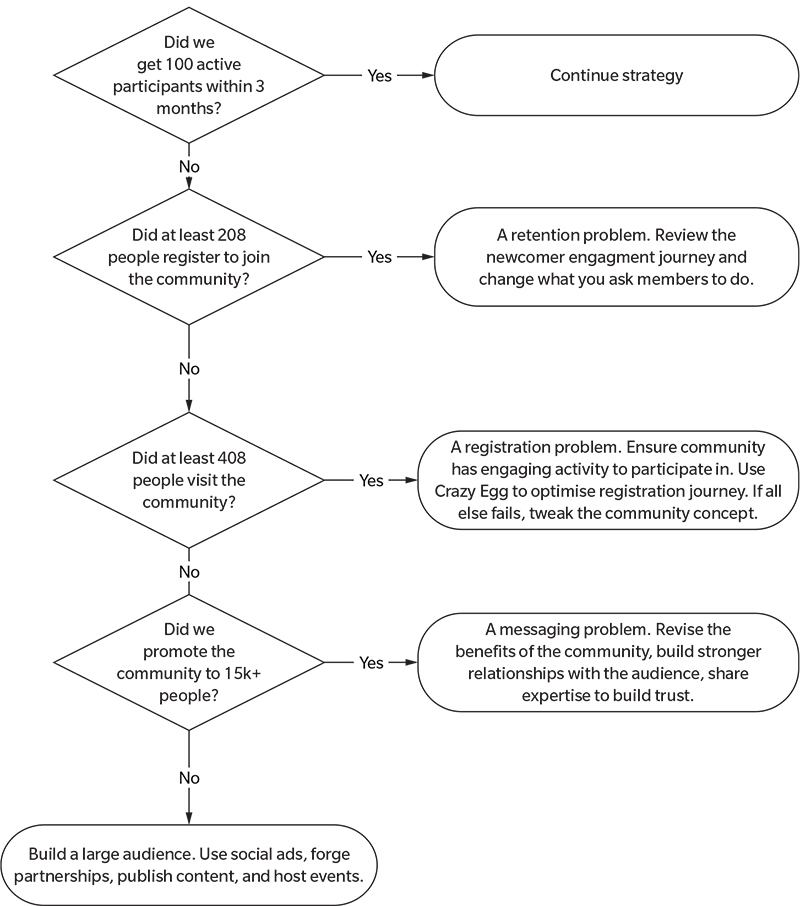

Remember, if your community isn’t gaining traction, the first step is to diagnose why. There are several questions you need to ask yourself here.

- Did enough people register to join the community? The most common problem is not enough people registered for the community in the first place.

In Chapter 5, I mentioned a typical community needs around 100 actively participating members for a community to sustain a critical mass of activity. But if you’re not getting enough people registering, you won’t be able to achieve a critical mass. The question then is what is the minimum number of people you need to register? This is where our benchmark helps.

You can see above that in an ex-small community (which a new community naturally is), a maximum of 48% (only half) will participate.17 If we need 100 active participants we therefore need at least 208 people to register for the community.18

If your community achieved that number, your problem isn’t getting enough people to register, but getting them to participate. You need to focus on what the journey looks like after someone joins. What are you asking them to do? What messages do they receive? What does that newcomer journey look like? You can tweak your user journey and gradually make improvement. You can use our template user journey at www.feverbee.com/buildyourcommunity (or use Smaply.com to create your own).

If your community didn’t achieve that number, we have to find out why. This leads us into the next question:

- Did we attract enough people to visit the community? You can’t get enough registrants if too few people visited the community in the first place. People typically need to visit before they can join a community. Looking back at our benchmarks again, we can see anywhere between 10% and 51% of visitors might register to join. If we use the best case scenario (i.e. a maximum of 51% of visitors will register),19 how many visitors do we need to get the 208 registered members we identified above? The answer is about 408 visitors.20

If you achieved this number, the problem probably isn’t getting enough people to visit but getting them to register. You need to look at what members see on the first visit. Is there an interesting, engaging activity that motivates and that members want to engage in?

Is the registration process easy to get through? Use Crazy Egg21 or a similar tracking tool to diagnose how members browse your community and reposition the registration option better in the member’s journey flow. Look at what most members are doing and make changes accordingly.

If neither of the above works, you have a concept problem. Your community concept isn’t resonating with your audience. Reexamine your member research and test different community concepts using webinars, offline events, and content articles until you find an idea that really resonates with the audience.

If you don’t achieve this number, then we need to continue our investigation and find out why not enough people are visiting the community.

- Did we promote the community to enough people? For many organisations, the biggest problem is struggling to get enough people to visit the community in the first place. This often happens when you don’t have a large email list, social media following, or web presence to begin with.

If we know we need a minimum of 408 visitors (remember this is the most optimistic scenario possible, you might need several multiples of this) and our benchmarks suggest only 2.62% of people click on links in email,22 we can roughly estimate we need a mailing list of 15,572 people23 to reach this number.

Don’t sweat if your mailing list isn’t that big. It definitely helps, but the conversion rate is a little misleading. For example, this isn’t a one-shot deal. You can send multiple emails to your mailing list. The click rate will decline over time, but you should be able to get more than 2.62% of your list to visit.

Also a mailing list isn’t the only way to promote your community. You can also promote your community through your website, via paid advertising, via promotion and partnerships. Over time, members will also find it via search and referral from their peers.

What matters is that your combined audience(s) (or networks) are somewhere in the 15,000 people. Obviously for private communities this number is a lot lower. But for a public community, it’s very hard to get going without an initial audience to invite to join the community.

If you’re reaching this number and not many people are visiting, you have a messaging problem. Either members aren’t seeing the value of the community or don’t trust you to deliver on the value you claim. You need to revise your messaging and try again. By the way, this is why you should be cautious about doing a big launch. You don’t get a second chance to make a first impression.

If you’re not reaching this enough, you need to grow the size of your initial audience. You need to steadily build up a following (ideally a mailing list) first. This might mean using social ads, forging partnerships with influencers and other organisations in the sector, or creating content and hosting events to get people to follow you.

If it helps, you can use the flow-chart in the following page to diagnose and overcome activity problems:

Overcoming problems

Note: This is a simplified version of a far bigger diagnostic tree. Get the full templates at: www.feverbee.com/buildyourcommunity.

2 Failure to sustain engagement

At some point in your community efforts, you’re going to face one of the most worrying problems of all: declining engagement. Believe me, no one wants to be at the helm when a previously successful community begins to sink. Don’t panic, you’re not sunk yet! But you do need to identify the cause of declining engagement and then develop possible solutions.

Declining engagement can be a good sign

In 2016, a client of mine was worried about declining levels of engagement.

We looked at the data and discovered that the number of visitors was higher than it had ever been. But fewer members were registering and fewer newcomers were asking questions. We ran a survey of members and soon uncovered what was happening. Visitors no longer needed as many questions; the majority had already been definitively answered in the community. The community had done exactly what it was meant to do.

Declining engagement doesn’t mean you have a problem. Sometimes it can be a great sign of success. Your community might’ve answered the majority of questions members are likely to have or your organisation might have been fixing the issues which have arisen in the community, resulting in fewer people needing to ask for help.

When you do see a decline in engagement, it’s critical to investigate the root cause. If you’re working for an organisation, you need the data to back you up if engagement does decline.

If a community engagement begins to decline, it’s because one of two things has happened: either something within the community has changed or something outside of the community (i.e. about your members) has changed (or some combination of both).

Changes within the community | Changes outside of the community |

|---|---|

|

|

This isn’t a comprehensive list, but it’s a good place to start. You need to figure out which category of problem you’re trying to solve. Trust me, this can save you a huge amount of time and resources. It’s always tempting when engagement drops to launch new engagement initiatives within the community. But if the cause of the drop doesn’t come from within the community, these will have no impact.

In my experience, community leaders zero in on visible problems at the expense of the real problem. One client felt grouchy veterans were driving away newcomers. However, in our survey and interviews, hardly any newcomers mentioned grouchy veterans as a problem. As we dived into the data, we discovered that the real cause of declining engagement was a drop in search traffic caused by a change in Google’s search algorithm.

Instead of spending a huge amount of time and energy persuading veterans to play nice, we solved the problem by removing several thousand discussions with very few responses (thin content) and adapting the community to meet the search needs of today. Once we had done this, engagement rose to slightly above what it had been.

The decision tree to fix declining engagement problems is too detailed to fit across a page in this book. If you want a simple process to follow, head over to www.feverbee.com/buildyourcommunity.

3 Losing internal support

I hate to tell you this, but if you’re being paid to lead a community, there is a reasonable chance that whoever is paying you will one day decide there are better uses for that money. Many, if not most, community leaders have at least one story of their organisation suddenly deciding to cut the budget for the community team. There are two common causes for this. The first is the arrival of a new senior executive (or CEO). This person has different strategic priorities and sees community as a luxury rather than a necessity. The second is a sudden change in the environment (often an economic downturn or a bad financial year). Many community leaders were made redundant as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This risk can be best negated in two ways. First, develop and continually update the stakeholder analysis we discussed in Chapter 2. You should be reaching out to every stakeholder each month to gather their current views on the community, what they want to see, and how they can be better involved in the process.

Second, send information to each stakeholder in the right format. That’s probably not going to be an excel spreadsheet attached to an email at the end of each month. It might be a monthly chat over coffee, a single image, a short video, or stories of members. Every stakeholder has different preferences you need to adapt your knowledge to.

Third, create a community steering committee composed of key community stakeholders who can meet once a month, review progress, address issues, and collaborate together on the way forward. This helps ensure broader understanding and awareness of the community.

Developing your risk analysis

A proper risk plan protects you, your community, and your organisation. It’s not just smart to do it, it’s a moral imperative to do it. There are three key steps.

Step 1: Identify the risks

Use the table below to identify the risks which are relevant to you. Remember this isn’t a comprehensive list. You might want to include other kinds of risk here too. For example, some clients have worried about competitors poaching their customers through their community. Others have been concerned about people from a specific geographical region participating in the community. Drop every feasible risk into a simple table like the one below:

Type of risk | Category | Specific risk |

|---|---|---|

Legal | Superusers | Superusers claiming their roles rose above the threshold of employment. |

Data privacy | Member email addresses, passwords, photos, or direct messages are hacked and leaked into the public sphere. | |

Ideation | Members claim credit or royalties for ideas implemented within the community. | |

Illegal content | Members sharing copyright material in the community. Members sharing illicit/illegal content within the community. | |

Competitions | Competitions are considered gambling. Competition violates laws of member location. | |

Minors | Minors join and participate in the community. | |

Bad publicity | Journalists discovering angry customers or hateful posts to write negative stories about the brand. | |

Angry customers | Inability to quickly and effectively respond to questions. Inability to involve members in decision making. Failure to respond to ideas and comments from members. Sense of injustice in perceived differences in member treatment. Poor behaviour from staff members upsetting members. | |

Leak of confidential information | Staff unintentionally revealing confidential information. Staff intentionally posting private information (typically recently departed staff). Friends of staff posting confidential information. | |

Risk to members | Conflict | Fights escalating from online to offline environments. |

Harassment | Members releasing private information about another member (phone number, address, hacked information). Members making unwanted advances towards each other. Members attacking each other via private messages (bullying). | |

False information | Members maliciously sharing fake information to trick or trap other members. Members writing self-promotional posts. Members being unintentionally given bad information by other members, which is not corrected by other members and could cause them grievance or considerable harm. | |

Decline in mental health | Environment which compels the community manager to constantly check in during time off. Long-term consequences of dealing with vitriolic statements. Inability to provide adequate care and support to staff members. | |

Victim of personal attacks or harassment from members | Members personally directly abuse the community team inside and outside of the community. Members make unwanted sexual advances. Community team profiles are hacked. | |

Risk of failure | Failure to gain traction | Members aren’t interested in the community. There isn’t a big enough audience to reach. Members are prevented from joining or participating through bad technology. |

Failure to secure or sustain internal support | Colleagues fail to support the community. Change in colleagues. New strategic priorities. | |

Technology failures | The platform isn’t working as specified. The specifications were unclear or poor. Breakdown in relationship between community team and platform provider. Community is flooded with spam. Unforeseeable change in circumstance. |

It’s a good idea here to ask fellow community leaders in your sector what kind of problems they encountered. You might be surprised to learn of potential dangers you hadn’t even considered.

Step 2: Estimate the danger

The next step is to estimate the likelihood (low, medium, or high) of each risk and the potential impact of the risk if it does happen (mild, medium, severe).

The likelihood is probably harder to estimate than its level of impact. You can estimate the likelihood by speaking with other community professionals, browsing the web for examples, and asking your colleagues about their opinions.

You can estimate the severity of impact by talking with different stakeholders (notably legal) and using your own judgement. You can see these dropped into the table below.

Step 3: Develop your mitigation plans

Now using the mitigation steps I’ve outlined so far in this chapter, your organisation’s resources, and your own expertise, develop your mitigation plans. You shouldn’t be writing this alone. This should be a consultative process. For each risk, outline your steps to either proactively prevent it from happening or resolve the issue quickly if it does occur.

Step 4: Assign a directly responsible person

As you can see above, we’ve also assigned a person to be responsible for mitigating each risk.

It doesn’t matter how good your mitigation plans are if you don’t act upon them. Someone needs to be responsible for each of these. If you’re the only person managing the community, you will be this person (in which case review the actions you’ve taken to mitigate these risks once per month).

If you’re working as a team, then set aside time once a month to update on potential risks and see if anything needs to change. During these meetings update the risk and likelihood of each item, check the owner is undertaking the necessary steps, and add any new items which have arisen to the list.

Summary

Launching your community should be an exciting adventure which yields incredible benefits to you and your organisation. Just don’t overlook the risks. You can’t prevent every possible problem, but you can take reasonable steps to reduce the likelihood and impact of each risk.

Risks tend to fall into five categories. You have legal risks to consult your legal team about. You have reputation risks to discuss with your marketing and PR teams. You have a risk to members which you should discuss with your colleagues. You have personal risks to you and your team. And you have risk of a strategy or execution failure.

Make a list of the potential risks facing your community and then come up with a plan to reduce or mitigate the likelihood or impact of the risk. Assign each step to a specific person and meet once a month to ensure the steps have been taken to prevent that risk from happening.

The purpose of this chapter isn’t to scare you, but to prepare you. You should be able to go forward with confidence that you have taken all necessary precautions to ensure your community thrives.

Remember this isn’t a one-off process. The bigger your community becomes, the higher the stakes. You have to continually add and adapt your risk analysis and actions. Only then can you build a community with confidence to tackle anything that might come your way.

Checklist

- Identify the risks you might face when you launch your community.

- List each risk by the likelihood of it happening and the severity of it happening.

- Develop mitigation plans to prevent or deal with each risk as it happens.

- Ensure someone is responsible for each plan.

- Meet as a team and review or update the plans each month.

Tools of the trade

(available from: www.feverbee.com/buildyourcommunity)

- Crazy Egg

- Google Analytics

- CMX Hub, FeverBee Experts, and Community Roundtable (consult with other community leaders to identify potential risks)

- FeverBee’s Risk Assessment Checklist

- FeverBee’s Decision Tree Templates