Outsourcing is one of the hottest topics in CIO circles today: a general online search yields tens of millions of hits; an online search through CIO magazine's online Web site alone yields tens of thousands of hits; a similar search on Harvard Business Review Online yields nearly 200 hits. It is also a hot topic in professional circles. A search on the IEEE and ACM portals limited to the past three years yields more than 500 hits. Outsourcing is clearly one of the most significant topics for senior managers in all industries and enterprises of all sizes.

Taking a step back from this overwhelming amount of information, what does outsourcing mean? This chapter investigates the many interpretations of outsourcing, but let's start with the proper definition from Webster's Online Dictionary:[67]

The practice of subcontracting manufacturing work to outside and especially foreign or nonunion companies.

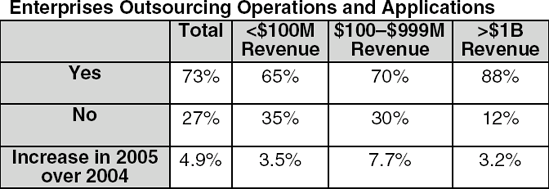

Although Webster's defines this as a noun, it is in practice more a verb: the entire process of proactively deciding and managing the what and why and how of business-to-business partnerships up front, during the ongoing activity in the middle, and while finishing up or cleaning up (if need be) at the end. Then there's the approach to outsourcing: is it "outsourcing" or "offshoring" or "outhosting" or "insourcing" or some combination of these? Perhaps first and foremost, is any form of outsourcing what you really need? In a recent survey by CIO Insight magazine summarized in Exhibit 7.1, nearly three-fourths of surveyed companies spent money outsourcing in 2004, and they expected their IT outsourcing spending to increase by almost 5 percent in 2005.[68] The same survey asked how the monies would be spent across a wide range of categories with application and Web development, application and systems integration, and application and Web hosting (including e-mail hosting) at the top of the list (see Exhibit 7.2).[69]

For the most part, enterprises that use outsourcing are satisfied with the return on their investments, and they plan to continue to invest at more or less the same spread as in the previous year.[70] This is very good news for the outsourcers, too. For every outsourcee there is an outsourcer! Because the heart and soul of CIO responsibilities is rooted in defining IT resources in terms of business goals and strategies, let's be clear about the definition of these two important terms:

| Outsourcee—The entity contracting-out with another entity to accomplish specified goals and/or objectives (deliverables). |

| Outsourcer—The entity that works to accomplish the specified goals and/or objectives (deliverables) of the outsourcee entity. |

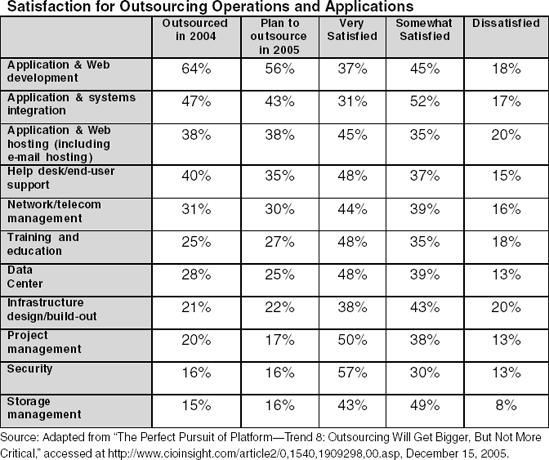

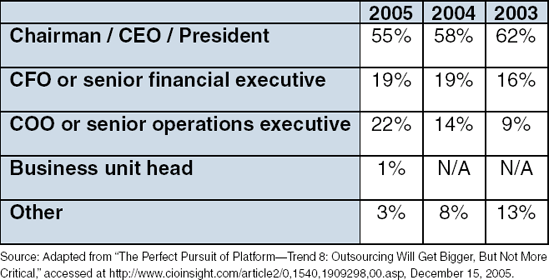

There seems to be no limit to what CIOs are willing to outsource, but the patterns speak volumes. When asked if they were willing to outsource strategic IT functions and applications, 43 percent of CIO respondents were willing to do so—meaning that 57 percent thought otherwise. What drives outsourcing choices in the minds of these CIOs? It is not solely cost savings—74 percent of respondents believe that outsourcing is overrated as an IT cost-cutting strategy. Other drivers include 24-hour/365-day coverage and development and skills availability (see Exhibit 7.3).[71] In fact, 51 percentof the CIOs said they had not cut full-time IT jobs when they outsourced to an offshore partner, and about two-thirds said that fear oflosing jobs to outsourcing did not have a disruptive effect on their organization. This may well be the result of the person to whom different CIOs report: CIOs who report to people higher up in the company are morelikely to have the necessary support they need to manage their budgets andresources in a way that optimizes the enterprise's objectives rather than the objectives of a particular function within the enterprise.[72] Although CIOsincreasingly report to COOs, the vast majority reports to the CEO (seeExhibit 7.4).[73]

Taking this preliminary outsourcing analysis farther into the future, what are business and technology researchers investigating and evaluating? From a business point of view, one of the greatest concerns (and, therefore, an area of significant active investigation) is the loss of "higher-order" capabilities employees bring to bear when directly applied. A "directly applied" employee actually performs the work; the "indirectly applied" employee guides and directs another person but does not actually perform the work themselves. Gary Hamel summarizes the issue and the solution provided by good indirectly applied employees: "It's tough to build eyepopping differentiation out of lower-order human capabilities like obedience, diligence, and raw intelligence . . . [A] company must be able to deliver the kind of unique customer value that can only be created by employees who bring a full measure of their initiative, imagination, and zeal to work every day."[74]

"Common wisdom" in financially driven business climates says that outsourcing saves costs. However, practitioners with operational responsibilities know that cost savings are only one of many reasons why companies outsource. The why is a continuing story whose end may never come. Today, the primary reasons (normalized) for outsourcing are shown in Exhibit 7.5.[75] It is worthwhile to take a look at each of these in turn.

For John Valente, a senior executive with more than ten years experience in this area,[76] cost did not even make it into the top three (it placed sixth). John's top three reasons for outsourcing are:

Pace/Speed: The ability to get more work done in the same time or to get work done that would not otherwise get done.

Talent: The ability to get access to "talent" that he was not able to find locally.

Innovation: The ability to get access to skills and specific productrelated experience in areas that he didn't even know initially he needed.

John does see cost savings advantages, but he sees them as fortunate outcomes that result from better upstream operational choices regarding people and processes. Let's take a look at some of the ways that cost savings derive from these better upstream choices.

The cost of labor around the world continues upward. The operationally minded CIO, however, focuses on the cost of skilled operations, development, and management labor relative to the skills level for that cost. True cost of labor is derived from a combination of a number of factors:

Cost of Acquisition

Salary: base salary

Bonus

Perquisites (aka "Perks")

Benefits

Costs of Retention

Support & Infrastructure Costs

Separation and/or Termination Costs

Skills Level(s)

Communication and Transfer Efficiency Factor

In most calculations of the true costs of labor, the first eight factors form the numerator and the 9th and 10th factors form the denominator. In other words, although the out-of-pocket expense for an individual outsource resource varies from business to business, the CIO must factor at least two important operational considerations for deriving the total cost of labor: (1) the skill level of the resource and (2) communication challenges involved in turning those skills into the anticipated value-added deliverables for the business. Take, for example, two separate situations:

Situation 1: "Your enterprise" is considering outsourcing to Company "A" based in Country "A".

Situation 2: "Your enterprise" is considering outsourcing to Company "B" based in Country "B".

Situation 1 Conditions of Company A: A multinational, financially very healthy company based in Country A. Your enterprise benefits from Company A's multicultural and multilingual workforce with its wide range of skills and experiences. Company A provides outsourcing services not only in its home country but also in your country and other countries.

Company A has labor costs that are said to be 20 percent of those in your enterprise but once finally calculated are approximately35 percent of those in your enterprise, and Company A has a high enough profile that it has name recognition with most (if not all) CIOs.

Conditions in Country A: This country has a neutral stance toward your country, being neither friend nor foe. However, your country's language is either the second or third language for the educated talent pool of Country A. Contribution and/or ownership requirements associated with doing business in this country demand that your partner must have a profitability objective with a reasonable event horizon (perhaps 5-7 years). It may be necessary to buy all supporting hardware, software, and other purchases through Country A-based companies or pay a significant tariff or duty on these items being imported into Country A. Last but not least, travel between your country and Country A is only marginally inconvenient.

Situation 2 Conditions of Company B: A non-multinational that only has offices and operations in Country B. The company culture and its predominant languages are different than your country's languages. Company B can provide outsourcing services only in their home Country B. Company B has labor costs that are said to be 15 percent of your enterprise but once finally calculated are approximately 25 percent of your enterprise. Company B has no real name recognition with most—if not all—CIOs.

Conditions in Country B:This country has a negative political relationship with your country. Your country's language is neither the second nor third language for the educated talent pool of Country B, though that situation is improving. Contribution and/or ownership requirements associated with doing business in Country B make it very difficult to ensure that your intellectual property can be adequately protected. It may be necessary to buy all supporting hardware, software, and other purchases through Country B-based companies or through suppliers who import what you need at significant tariff or duty. Travel between your country and Country B is fairly inconvenient.

So, which situation is more appealing? Which situation makes more sense? Which situation would be the better choice? It depends. John Valente's view is that "outsourcing never saves you money: if you were disciplined enough to do it yourself you could get the same margin of savings." Although cost savings may not be sixth on everyone's list, take a closer look if it falls on the top of your list.

At this point, a cry of "foul" might be heard. How can it be that cost savings are not the top reason (maybe the only reason) for outsourcing? However, Exhibit 7.6 is legitimate. Many enterprises have been "outsourcing" for decades for the reasons mentioned earlier in this section. The point made in the first chapter's section called "Strategic IT Questions–Starting from Scratch" applies: learn from your experiences, but remember that what happens in the future will be different in some important respects from your past experience—especially because this is such a rapidly growing and maturing practice.

The point of Exhibit 7.6 is that there are costs and there is total cost. There is more to costs than just wages and apparent cost of living; to even begin to approach total cost the CIO starts with wages but also has to account for (1) direct and indirect costs, (2) relationship management resources and expenses, (3) program/project management resources and expenses, (4) capital and equipment expenses including export/import and shipping, (5) changes in project scope or requirements or designs, and (6) risk factors that can contribute significantly to total cost. Such risk factors include: [77]

Geopolitical risk: includes stability of government, corruption, geopolitics, security

Human capital risk: includes quality of educational system, labor pool, number of new IT graduates

IT competency risk: includes project management skills, high-end skills and competence (custom code writing, system writing, R&D, business process experience)

Economic risk: includes currency volatility, GDP growth

Legal risk: includes overall legislation, tax, intellectual property

Cultural risk: includes language compatibility, cultural affinities, innovation, adaptability

IT infrastructure risk: includes IT expenditure, quality of key access infrastructure

The combination of these risks for each country and for each company may have a major effect on the total cost of outsourcing. For example, using Exhibit 7.6 as a basis, if "your enterprise" profile matches Situation 1 for evaluating an outsourcing relationship between your IT operations and an established company in India, your evaluation might look like this: [78]

Costs are Very Low.

Risk is Medium based on:

Geopolitical risk: medium based on stability of government, corruption, geopolitics, security

Human capital risk: very low based on quality of educational system, labor pool, number of new IT graduates

IT competency risk: low based on project management skills, high-end skills and competence (custom code writing, system writing, R&D, business process experience)

Economic risk: very low based on currency volatility, GDP growth

Legal risk: medium based on overall legislation, tax, intellectual property

Cultural risk: very low based on language compatibility, cultural affinities, innovation, adaptability

IT infrastructure risk: high based on IT expenditure, quality of key access infrastructure

Total Cost therefore appears to be Low (rather than Very Low)

It would not be difficult to imagine a series of factors related to the choice of outsourcee country that would cause the risk to rise to High or Very High with a corresponding change from "costs" to total cost being a factor of up to 5. Such a change would be enough to make the outsourcing for that particular situation unaffordable.

Let's round out the remaining additional costs that can significantly contribute to the total cost of outsourcing listed at the beginning of this section:

Relationship management resources and expenses are incurred to manage the ongoing relationship at the management, supervisor, and organizational level. There may be additional expenses required to integrate outsourced work back into your enterprise infrastructure.

Program/project management resources and expenses are incurred indirectly to liaison and manage the outsourced program/project with the outsourcing partner. These responsibilities commonly consume a majority of time or even become a full-time job for someone in the enterprise. Naturally, there may be travel or other expenses associated with doing so.

Capital and equipment expenses including export/import and shipping are incurred to provide required equipment, and if specialized environments are required, facilities upgrades and/or enhancements to allow the outsourcing partner to perform their contracted activities. These expenses may be fully or partially included and spelled out in the contract or may be wholly left for your company to provide. There are trade-offs to be made in deciding whether to buy equipment in the outsourcing partner's home country or to buy it in your country and ship it. Many enterprises do both: purchase common off-the-shelf IT equipment in the outsourcing partner's country and the specialized capital equipment in your company's country for shipment to the partner's country. This approach adds two levels of complexity for the CIO outsourcing to a company in a foreign land: ensuring the legal export requirements for one's home country and the specific equipment and the legal import requirements and duties for the outsourcing partner's country. All these costs may not be visible in the planning stages and may surprise people when they show up in a calculation of the total cost the enterprise eventually pays forthe outsourcing relationship.

Changes in project scope or requirements or designs are costs incurred when an enterprise alters course, learns that something was forgotten, or fails to fully consider and account for the important variables.Work-in-progress costs are much like additional charges incurredbuilding a new house when the homeowner decides to change the design or change some appliance after work has started. Work-inprogress changes generate a "change order" or "work order" that nearly always result in additional charges. Experience shows that noamount of careful planning can predict all work-in-progress costs, therefore build a contingency plan (or contingency budget) toaccount for them. The old saying still applies: cost, performance (schedule), and quality—choose any two.

While any number of these cost factors may be present in situations where an enterprise is not outsourcing, it is easy to forget about invisible, in-house work assumptions that may end up being a realized expense when outsourcing and "costs" becomes total cost. Nevertheless, additional outsourcing benefits complement carefully planned cost management.

From an outsourcer's point of view, access to key skills may seem like a weak motive in the initial wave of outsourcing considerations, but it hasactually been one of the strongest motivators for many of the U.S.-basedmultinationals for years. IBM has reaped the advantages of this outsourcing resource for years. IBM has had major research and development laboratories in the major industrial countries for decades—not because these sites were the best "price performers" but because they possessed critical world-class talent that provided significant contributions to IBM's products, revenues, and profits. These outsourcing sites provided bases from which IBM could conduct business in the site countries. Brilliantly, IBM places native citizens in senior management roles ofthese sites, staffs these sites with native citizens, and cycles through U.S.– based managers and individual contributors on temporary assignments tohelp cross-pollinate company and country cultural understanding. All IBM sites emphasize an IBM culture base, yet each site has its own uniqueblended culture that combines IBM culture, the site country's culture, and the site's individual local culture. But make no mistake, when people walk into any IBM facility they walk into IBM itself, and the employees call themselves IBMers.

Emerging countries now bring a significant number of talented and skilled resources. Dr. Rick Rashid, Vice President and Head of Microsoft Research, has first-hand experience with this trend. He is responsible for defining, creating, and staffing the heads of Microsoft's research laboratories worldwide. Dr. Rashid has explicitly focused on culture as an important element of attracting and retaining the key skills Microsoft Research needs while ensuring the Microsoft corporate culture is not lost.

There are cultural differences, but the dominant "culture" in each of the labs is MSR [MicroSoft Research] culture. Senior people typically trained in the US or Europe already and may have worked in Redmond so they already bring that perspective. For the younger people, a lot of our training focus is to bring them into the western research culture. We do language courses where needed, help teach research and writing skills, and our managers model behavior. Obviously there are still some culturaldifferences, but they mostly give a cultural "tint" to the labs rather than provide the dominant theme.[79]

John Valente's approach with Accenture for Best Buy also stresses the importance of melding local and company culture. And, for understanding other cultures, John highly recommends the book Kiss, Bow, or Shake Hands.[80] Culturally sensitive approaches are also important to the outsourcee's employees, or in the case of wholly-owned subsidiaries, to the company subsidiary's employees. It gives them both a local identity and a corporate identity and becomes the context in which their endeavors contribute to overall company success.

From the outsourcee's point of view, the outsourcer's skills access dilemma is a business opportunity. Successful outsourcees must supply access to the skills required by the outsourcer at the right time and the right place. This usually means that the requisite skills need to already be on-board in the outsourcee company. For boutique outsourcee companies, this generally means moving from project to project (singly or in small numbers) and careful planning to avoid resource conflicts due to unscheduled overlapping ofprojects. Larger outsourcing companies manage a balance of their resourcesto a higher number of employees and skills mix than their least demanding activity, and optimally, just high enough to meet the requirements of their most demanding activity. This forces a "wedge" because employees are notalways fully employed, but it is necessary to ensure that they capture all key opportunities.

Many countries require that a company have a country-based subsidiary or country-based operations to do commercial business. One way of achieving this is through an outsourcing partnership with a company that can also be a distributor for outsourcee products or services in the outsourcer country.This presents advantages from the outsourcee's perspective becausethey obtain a wider range of products and services (and therefore revenue and profits potentially).

Experts and educational curricula abound on the requirements of doing business with many, if not all, probable countries. For example, CalTech University has a course called "Doing business with India"; [81] Squire Sanders Legal Counsel has a consulting arm and uses a document called"Doing Business in China";[82] Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer consultants produced a document called "Guide to doing business in Russia"; [83]the US Commercial Service developed a document called "Doing Business in Slovenia: A Country Commercial Guide for U.S. Companies," published on the "buyusa.gov" Web site[84]—to name just a few. Behind every such publication, experts with (and without) personal experience work throughthe requirements of doing business in other countries. Examples of specific requirements and challenges for doing business in other countries appear in the proper context throughout the remainder of this chapter.

From the outsourcer's perspective, outsourcing presents the potential for significant productivity improvements, particularly when leveraging time zone differences. In a very common product service and support realm scenario, the support "follows the sun". As "noon" moves from East to West the service center people supporting a particular product of organization transfer from a location in the East to one in the West and repeat this transfer to and from every 24-hour period. The simplest way to accomplish this uses two or three equally spaced geographic service and support regions spaced 12 or 8 time zones from each other. Most large multinational corporations now use this method to provide 24/7 call center support andmany (such as international airlines and service-oriented groups such as IBM Global Services and Unisys) have done so for decades.

Enterprises involved in outsourcing product development or application development can create productivity improvements by performing development, testing, debugging, fixing, and revalidation around the clock—literally. Xiotech Corporation uses several methods to increase outsourcing productivity with a multiregional workforce. Let's look at two:

Split development and Quality Assurance/Test: In this method, people perform development work in Time Zone 1 and Quality Assurance/ Test (QA/Test) work in Time Zone 2. As development proceeds in Time Zone 1, people in Time Zone 2 test incremental improvementsto the product. By the time the people from Time Zone 1 arrive for work the next morning, Time Zone 2 people have prepared and sent the triage results of the testing. The Time Zone 1 people then review the test results, make the necessary corrections, and address those corrections for testing by the Time Zone 2 people come in the next morning.

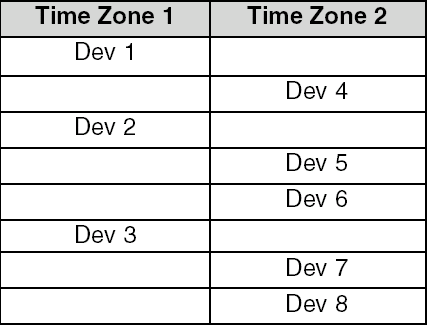

Cooperative Development and Quality Assurance/Test: In this method, both development and quality assurance/test occur during each time zone. This requires more sophisticated processes and management to work optimally, but the reward is obvious: 24-hour product development. When organized so that the development and quality assurance have a specific Time Zone 1 team member partnered with a specific Time Zone 2 team member, people can pick up where the others left off.[85] This is called "GeoPairing." And, thismethod provides some protection for loss of skills should the project lose one or two people. Typically, staffing skills differ from taskto task across time zones. One zone may be very strong in one areabut weak in others. In this case, the CIO works to coordinate acomplimentary pairing of the skill levels and work people performin each zone. Consider an example of an eight-person developmentteam with three people located in Time Zone 1 and five people inTime Zone 2 where the three in Time Zone 1 have overlapping technical and experiential skills—but generally higher than the fivein Time Zone 2. As illustrated in Exhibit 7.7, coordinating a complementary working relationship might pair Development Team Member 1 (Dev 1) with Team Member Dev 4, Dev 2 with Devs 5 and 6, and Dev 3 with Devs 7 and 8. If there were Dev 9 and 10 in Time Zone 1 it would also be possible for Dev 8 to take the lead in a group consisting of Devs 9 and 10 (of course Dev 8 would not be associated with Dev 3 in that case).

The sophisticated management challenge involves how to ensure overlapping efficiency and avoid re-creating work done in the previous period. In both methods, the outsourcee benefits from a tighter relationship with the outsourcer and therefore is more likely to see a flourishing and longer-term relationship.

As with "follow the sun" development and/or service and support, an enterprise that leverages time zone and geographic differences also adds a degree of improvement in business continuity to its competitive attributes. Deploying round-the-clock development and/or operations (and therefore probably backup) could provide the basis and/or base of operations for business continuity in the event that either the outsourcee or the outsourcer has a critical failure.

For example, Northeastern University[86] uses off-hosting where its applications and its hardware reside at a SunGard location. This service provides tremendous value for Northeastern. SunGard hosts Northeastern hardwareand applications if the primary site is down anywhere in the world they areneeded. SunGard (www.sungard.com) is a $4B company whose claim to fame is the ability to provide business continuity with replica hardware that allows customers to run their own application(s) should their own primary equipment fail or become unavailable. The replica hardware, and associated software, can be located anywhere with suitable networking bandwidth, power, and security.

In fact, SunGard has facilities in 50 countries. Geographic dispersion means that even when disaster strikes at 3:00 A.M. there is at least one site around the world where it is normal business hours and that staff can bring your applications back online. According to Hoover's International Online,[87] SunGard has 14 competitors. In reality, it has an almost infinitenumber of competitors because many companies do this themselves with their own geographically dispersed sites.

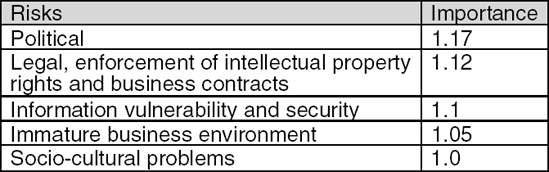

Just because something can be outsourced does not mean that it should be outsourced. There are many risks associated with outsourcing for both theoutsourcee and the outsourcer. A recent survey of more than a hundredsenior IT managers in different companies in the United States and Europe identified five key risks associated with outsourcing summarizedin Exhibit 7.8. [88]

Many more risks exist than uncovered by this survey—and some may be even more important than the five in the survey. Additional risks include, ordered from highest to lowest risk:[89]

Frequency of interactions required

"Hearing" versus "understanding" calibration

Skills and experience normalization required

Time-shifting requirements

Equipment handling and management

Given the risks and the potential for catastrophic consequences, what means do successful CIOs use to decide whether or not to outsource? Itwould be a significant mistake to outsource the enterprise's core intellectual property. However, to outsource the added support needed for anexisting product in a new environment where the new environment is too risky to use in-house resources may be an excellent limited risk scenario.From the outsourcer's perspective, they do not want to take on what canbe seen from the beginning as a certain failure. One of the most insightful books in this area is Attracting Perfect Customers: The Power of Strategic Synchronicity [90] by Stacey Hall and Jan Broqniez. They describe that to be successfulwith each other (as adapted for our purpose), both the outsourcee and the outsourcer need to be clear on their mission and cultural fit:

Be clear about who is being served

Hire only people truly aligned with the mission

Ensure that products, management practices, and organizational structures all align with the mission

Measure how well the organization achieves its mission every day

Trust that the money naturally follows when work is true to the mission:

A business that stays true to its mission is an "attractive" business. An attractive business is one that is standing still and solid, emanating the light of its mission, so that its most perfect customers can easily find their way to the company.[91]

Once the decision has been made to outsource, the next question is:How? The answers to several fundamental questions point in the right direction:

What are we going to outsource?

Why outsource? What benefits do we expect?

What level of our business activities are we outsourcing—strategic, developmental, operational, or . . . ?

Are we outsourcing something that crosses organizational boundaries?

Does the outsourcing relationship include significant knowledge transfer?

Does the outsourcing relationship require significant equipment transfer or acquisition?

Are we outsourcing something with significant tie-ins back to the origination point?

Do we have a management or corporate mandate to outsource?

Is this our organization's first outsourcing project?

Is this the first outsourcing project you have done?

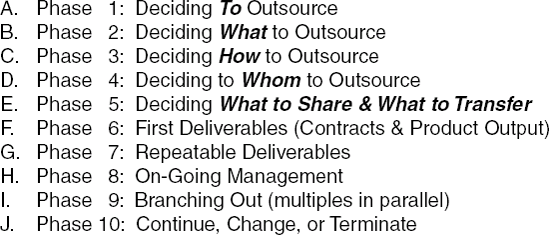

There seems to be no limit to the "resources" that address the processes for starting outsourcing projects where process advice ranges from the "justbarely enough to call it a process" to "more than would be required to pass ISO 900x certification"—much like Emperor Joseph II's "Too many notes" complaint about Mozart's compositions. In other words, there can be too much of a good thing. Experience shows[92] a common thread for initiating a plan and starting an outsourcing project. This section strikes a happy medium by discussing a step-by-step process that assumes little or no prior experience with establishing an outsourcing relationship by using the list in Exhibit 7.9 as the skeletal structure for the details of each step.

CIOs define IT resources and strategic opportunities for the entire enterprise, so start with (1) the definition of what it is that is going to be outsourced, (2) a clear agreement on why the outsourcing is being done—the rationale, and (3) the benefits expected to be realized from the outsourcing. All three elements must be defined up-front because they eventuallyneed to be communicated to the outsourcer, the outsourcee, and their respective teams. The outsourced item can include new product development, product testing, ongoing product maintenance and support, IT operations, IT application development, hosting of applications and subsequent maintenance, call center support, installation support, and break/fix support toname a few.

Next, the CIO must thoroughly understand the rationale for outsourcing. This affects the focus for the steps that follow and the final contract negotiation. For example, if the primary outsourcing objective is to reducecosts, then the outsourcing project will be defined and negotiated as a costsavingsventure. On the other hand, what if the primary outsourcing objectiveis to develop a variation of an existing project and to use the outsourcing relationship as a means of quickly developing this capability in parallel to other activities currently in place? In this case, the outsourcing project should be defined and negotiated as one or more statements of work or work orders and negotiated on features and functions, delivery, quality, and cost bases.

Finally, the benefits expected from the outsourcing relationship need to be defined; these reveal how the outsourcing project is expected to finishup—a vision of the end-state and end-result. The CIO must articulate thisvision at the beginning of the process as something to guide the project asit progresses and ensure that the project stays on the path to achieving the end-goal. For instance, if the CIO expects that application development can be taking place essentially 24/7 ("follow the sun") as the project's primarybenefit, use this as the litmus test to which the outsourcing projectmust be measured, and make it clear up-front that this holds for both the outsourcer and the outsourcee.

At this stage, the CIO must create a timeline with milestone deliverables that map out how to get from survey to project kick-off. An example is a timeline for outsourcing the development of a software-based product. For this particular product, the timeline and deliverables looked like:

First two weeks of March: Identify the dozen or so potential outsourcing partners; create and populate survey spreadsheet.

Third week of March: Complete survey spreadsheet with available information.

Last week of March: Issue Request for Information (RFI).

First week in April: Completed spreadsheets due back from potential outsourcing partners.

Second and third weeks in April: In-person meetings with U.S. contingent of potential outsourcing partners.

Third week in April: Notify qualified finalists for Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA) and Request for Proposal (RFP) distribution.

Last week in April: RFP distributed and telecon to answer any questions.

First week in May: Distribution to potential partners of clarification document.

Second and third weeks in May: Onsite visits to potential outsourcing partners for due diligence.

Third week in May: Product planning document draft.

Third week in May: Select and notify winner.

Last week in May: Complete contract negotiations.

Last week of May: Architectural document draft.

June 1st: Sign contract; start project.

August 1st: Begin Phase 1 Customer pilot.

August 31st: Release to Manufacturing (RTM); i.e., make the product available for sale.

After completely identifying the definition, rationale, expected benefits, and timeline it is time to do a survey of potential outsourcing partners. This canbe accomplished any number of ways, such as performing a simple Websearch, reading surveys of outsourcing companies produced by IT analysts, obtaining input from a professional colleague's network, and employing aconsultant to partner with a company that worked with yours in the past. The survey forms the basis for potential outsourcee analysis and is the base "companyprofile" information for the Request for Information analysis—the nextstep in this process. Spreadsheet tables are the best way to organize this information where the columns show the information to be gathered and the rowsshow the potential outsourcing partner companies. Column topics include:

| Company Name |

| Company Headquarters and Key Contact Information |

| U.S. Presence |

| Public or Private Company |

| Number of Employees |

| Hardware Expertise |

| Operating System & Utilities Expertise |

| Applications Expertise |

| Operations Expertise |

| Accreditations (e.g., Microsoft Certified Partner, SEI CMM Level, ISO 900x) |

| Business Models |

| Project Types |

| Customers |

The information required for these columns is generally available through a Web search; the information can be updated as responses and additional information become available. Expect to see three to four times the number of companies on your list than will ultimately receive Request for Proposal (RFP) letters.

At the survey stage, it is both too early and unnecessary to weigh the topics. It soon becomes obvious which of the potential partners meet your criteria. For example, if you have a need for significant hardware experience, strike those companies in the survey off the list that lack such experience. Or, if one prospect already has a relationship with one of your direct competitors, you either eliminate this prospect or look for ways thatthey can guarantee no cross-information transfer. Once the list is narroweddown to those companies that would appear to qualify, the next step givesyou more detailed information: create and issue a "Request for Information"letter.

After completing the survey analysis, write and issue the Request for Information (RFI) to those remaining on the list. The purpose of the RFIis two-fold: (1) gather more detailed information applicable to your specificrequirements from the potential partners and (2) provide a vehicle to meetand interview the principles (or their representatives) of these potentialpartners. The meeting/interview is particularly important in getting the first "up close and personal" measure of the potential outsourcee. Write anRFI that is more detailed than the survey and less detailed than the Request for Proposal (RFP). The RFI focuses on gathering detailed capability and operational information to narrow down the field of potential partners to "the few", and the RFP focuses on narrowing "the few" downto "the one".

There are two parts to the RFI: a spreadsheet and a document. The spreadsheet columns added to those from the survey with additional columns can include:

| System Software Utilities |

| Operating System Environments |

| Programming Languages |

| Development Environment |

| Development Processes |

| Experience with Similar Requirements |

| Ability to staff the project on the required timeline with skilled and experienced people |

Fill in these columns with detailed information you receive from the responses to the issued RFI. To ensure appropriate analyses of this information, weight the values in each of the columns according to your enterprise priorities. Weight each value by analysis of the importance of each ofthe evaluation criteria relative to one another using one of two approaches for weighting factor scales: relative or absolute. Relative scales emphasize the importance of each evaluation criterion as being the same or higher or lower than the other criteria. One of the criteria is determined to be highest, lowest, or middle and the remaining criteria are comparatively evaluated and placed in relation to the middle or ends. With relative scales, more than one criterion can have the same weighting. Absolute scales emphasizethe importance of each evaluation criterion regardless of the importance of the other criteria. Although it is possible for more than one or two criteria to have the same weighting value, the old saying still applies, "If they are all the highest weighting factor then they are all the lowest weighting factor, too."

The document portion of the RFI can be as straightforward as an e-mail used to transmit the spreadsheet and the schedule expectations as described in the RFI letter. Appendix 7.A shows the format of a Request for Information. Sending the RFI letter to potential outsourcing partners usually yields a 75 percent return rate. After the teleconference, about 50 percent move on to the face-to-face visit stage. Following the face-to-facemeetings, the field usually narrows another 25 percent. So, if 12-16entered the race, the field drops to 3-4 contestants for an on-site visit, but it all starts with the survey.

In the next step for selecting the best outsourcee, the CIO reviews the RFI submissions and decides which potential partners will be invited to presenttheir proposals in person for more detailed discussions based on theresponses. This decision should correspond to the results of the weighted analyses with the additional stipulation that if any of the critical requirements regarding skills, experience, or availability score very low, the CIO automatically removes the candidate company from the going-forward list. Those who have made the going-forward list should be notified through an e-mail or letter (see Appendix 7.B).

After finalizing the date, conduct the meeting within one week to ensure timely analyses with the information fresh in mind. A sample agenda for those invited to present in-person appears in Appendix 7.C. The length of meeting depends on the level of detail required for the discussions; however, a good rule of thumb limits the meetings to 90-120 minutes forcing a focus on their roles and yours. It is very important for the outsourcer's people who will be based in your enterprise with whom you will deal on a regular basis attend in-person. This allows you to begin to develop the necessary face-to-face relationships and take the "measure of the person".

Your review of the findings from the in-person meetings usually results in three to four stand-out potential partners: the ones you will contact andtake to the next phase, the Request for Proposal. Promptly notify those outsourcee representatives who did not make it to the short list and give them the reasons why they did not make the cut. This is important feedback to them, and it leaves an opening for them to participate in a future RFI. Also promptly notify representatives from potential outsourcee companies who did make the short list that they will soon receive an RFP with a schedule for the RFP process.

Candidates selected to receive the RFP show a high level of interest in the project(s) and as far as can be determined possess skilled and experienced people available to work on the project. Issue the RFP by e-mail or letter with the invitation and the required schedule. Additionally, this communiqué should introduce the expected in-person visit dates. An example e-mail or letter with timeline expectations for each of the finalists is providedin Appendix 7.D.

The contents of an example RFP are outlined in Appendix 7.E. Effective RFPs are carefully constructed to state the goal(s) and scope of whatis to be done, to identify the skills believed to be required, contract information requirements, and specifications of the work to be done, qualifications of the key people who need to be involved, pricing and evaluation criteria, and more general information such as deadlines, intellectual property rights, publicity, and contact information.

Unless you explicitly declare otherwise, your enterprise will be expected to provide marketing or user requirements and product architecture guidancefor the project. The potential outsourcing partner can be responsiblefor design, development, integration, and testing the work output to the point defined in the RFP. After release (acceptance), the outsourcing partner can be tasked with providing additional enhancements (Phases 2 and 3, for example) based on new requirements defined by your enterprise. Theseadditional requirements can be added to your base agreement through mutually negotiated addendums.

After distributing the RFP to the potential partners expect to receive any number of questions as they analyze the RFP and prepare their responses. Although it would be tempting to answer each question as it comes in, doing so generates a significant amount of duplicate work and could result in inconsistent responses that would have to be corrected by subsequent communications. Therefore, the best approach is to collect the questions, make them non-company-specific, and subsequently distribute the accumulated questions and your responses to all RFP responders. They all get the benefit of each other's questions and you get the benefit of all their responses!

Now analyze all the responses based on the criteria established earlier and the qualitative information available. Though procedurally similar to the earlier "review and select" step, this step narrows the number of potential partners to those finalists who will be visited in person.

It is nearly impossible to generalize the analysis of the RFP responses. In fact, the process requires flexibility because the different candidate responses usually show as many similarities as differences. However, experience shows that several areas should receive careful attention. The response should demonstrate that the potential partner clearly understands what you want them to do. This is important because the detailed responses in the RFP are usually completed by those who will be doing and/or managing the work. It is also important to watch the cost base: when one response is significantly different from the other responses (either high or low) it couldindicate a lack of understanding of the work involved. Watch closely forhow changes to the requirements while the project is in process are handled and how those changes are paid and accounted for from the base.

In the end, carefully examine the expenses associated with necessary trips to and from your facility by any members of the outsourcee's team, and look for additional costs associated with them. Consider this carefully and assume it will happen. Whether they are covered in contingency funds or in the project budget the money has to come from somewhere. Budgeting for one trip a quarter would be a reasonable place to start. John Valente has quarterly in-person meetings with his team alternating between Best Buy headquarters and the non-U.S. member sites. Additionally, because his staff also travels to and from non-U.S. sites someone from Best Buy headquarters can almost always be found at the non-U.S. sites some part of every month.

The decision about whether to make a site visit is an important one. Although it may seem extravagant, rest assured: it is not. The site visit provides the means to ensure that the potential partner has the ability, people, equipment, means, and wherewithal to realize the results they have promised. Don't forget your visa and other requirements for visits to different foreign countries. For some countries, an invitation to visit is required for visa approval. A letter or e-mail, similar to Appendix 7.F, prompts the potential partner to respond with an invitation to visit. There may also be recommended medical preparations advised such as inoculations; visit your local physician or international travel clinic to be sure.

It is highly recommended that travel be scheduled for arrival a full day early to ensure that your team recovers from jet lag and the first of the meetings are fully productive when traveling overseas or a long distance for the site visits (especially for those who do not regularly travel internationally). Failure to do so could easily result in a very painful first day's meeting and not allow full consideration of the first site visit when several visits are scheduled sequentially. It is also recommended that two people make the site visit(s); this reduces the likelihood that something said or covered (or not) is missed. Combining notes at the end of each day while the memory is fresh is essential.

Once the visits are completed, a final review of notes and impressions is a prerequisite to the final evaluation from the site visit(s). Site visits can provide other benefits. For example, they establish relationships that may be of value in follow-on projects, a comfort level gained from knowledge of the potential partner's environment, and insights into their working environment. Once you have returned from the site visit(s), re-review the RFP responses and cross-correlate them with the results of the trip. Now you are ready to make the final selection of two candidates with whom you make final negotiations.

You are now at the point where it is time to choose the two companies with whom you will negotiate a final contract. Negotiating with two candidates not only shows a final balance of their attributes but also ensures that you are able to reach agreeable terms with at least one. The ultimate objective, of course, is to select the best. Of course, what you really select is the right choice—the best choice may become evident some time in the future but much later than matters, in reality.[93]

Now that you are down to two choices, the time has come to tighten up the expectations on what, when, how, how much, and quality. This will again be a matter of trading the how much for various levels of the other expectations. Experience shows that the negotiations and contracts are best handled in your country's currency—not the currency of the potential partner's country—because managing the partnership will be much easierfor you and your enterprise when the budgeted amount(s) do not fluctuate month-by-month with changes in currency values. Although this means there may be a cost savings missed if currency movements happen in your favor, you are also shielded from fluctuations to your detriment.

It is also a good time to review the negotiation and communication culture and norms for the potential partner's country while preparing for thefinal negotiations. There are many strategies to use for negotiating the contract; too many to delve into for this chapter. Once the contracts arenegotiated to their right points it is time to decide which contract to choose to sign. The probability is high at this point that either contract would be fully acceptable, so the final choice is most likely going to be made based on the references provided of successful projects in a similar area and your final analysis of which potential partner more closely matches your enterprise culture, style, and approach. Once the final choice is made, both parties need to be notified and the project officially started.

It may well be that the company that did not win the business may ask that they be allowed to run a parallel project at their own expense as a learning exercise and—of course—an opportunity in case your other contract does not work out. This may consume time and resources from your enterprise but does not consume funds directly. If the capacity and inclination exists, then the loser's willingness to learn could be a very good contingency plan and a potential trial run that brings a secondary partner up-to-speed. This puts the "loser" and you in a comfortable spot for future possible projects.

Both teams—and senior management—are probably anxious to get the project started by the time the contract negotiations have ended and thecontracts signed. This pending excitement can be shared and the anxiety reduced through an official "kick-off" meeting. Such a meeting could be centered around the official signing of the contract(s) or could coincide with the first meeting of the two companies' project teams. It is always a good idea to start out on the right foot, and the business and personal bonds formed early on will undoubtedly be needed and tested as time goes on. Kicking-off the project also gives the operational and senior management an opportunity to review the expectations, to ensure joint understanding of those expectations, and to meet the team charged with making the project(s) successful. Do not shortchange this step.

Once the contract is signed, the project team is in place, and the project has been kicked off, it is time to move immediately into "manage" mode. Outsourcing, offshoring, outhosting methodologies are not "set it and forget it" operations. The first CIO responsibility is that of "trust but verify". The specifics vary depending on what exactly is being outsourced and by the maturity of the organizations (outsourcee and outsourcer), but take the time to periodically review relationship progress as it unfolds over the first months according to the document.

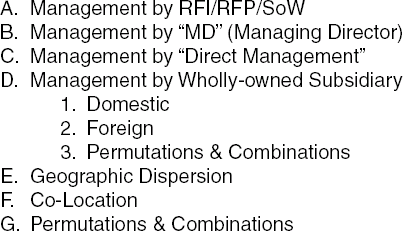

There are a multitude of ways to manage the what of outsourcing. Exhibit 7.10 lists a few of the more important methods, and each merit a brief description. When using Management by RFI/RFP/SoW both outsourcer and outsourcee focus on the document, and all activities are governed by and through the document and its constructs. When using Management by "MD" (Managing Director) the focus and communications are through the Managing Director as the management entity with the responsibility, authority, and accountability for outsourcing management.

The Direct Management method uses a peer-level manager-to-manager structure between the outsourcer and outsourcee, yet the entities are separate. In Management by Wholly-owned Subsidiary the relationship between the outsourcer and outsourcee is more one of multiple groups working toward a common goal (both working for the "same company" as opposed to one doing work for another company).

The Geographic Dispersion method spreads the organizations across time zones and/or countries and/or continents taking advantage of "follow the-sun" activity and disaster resilience. When using Co-Location the outsourcer and the outsourcee work in the same location allowing closer and higher bandwidth interactions. And, of course, permutations and combinations of these methods are more often than not becoming the norm. The RFI/RFP selection process is the best time to anticipate and sort out choices for the what and the how of outsourcing management.

As the relationship matures and proves itself successful, ongoing outsourcing management opportunities can run the gamut of product and/or applications development, testing, service and support, operations, call center, planning and forecasting, financial instruments, or even the actual hardware and software infrastructure (also known as outhosting).

In terms of a full or partial development cycle, product and/or application development may not be the first type of outsourcing that comes to mind; yet, it can become the most rewarding professionally for the outsourcer and the outsourcee as the relationship matures. Testing is often the first type of outsourcing that comes to mind particularly for product or applications development organizations. Look for opportunities to add and manage testing services from the outsourcing partner.

Service and support may not be an obvious outsourcing type; however, many companies find it advantageous to take advantage of a partner's "reach". For example, companies like Unisys and IBM Global Services have made a significant business of providing "break/fix" and parts logistics support for companies of all sizes as part of their ongoing outsourcing management activities. Call center staffing and management is another attractive outsourcing opportunity after the outsourcing partner has established its English language and customer relationship competence.

Operations is more likely to be done via outhosting and is not used as an outsourcing alternative as frequently as it was several years ago, but it remains a very popular opportunity with the right partner. Planning and forecasting, capital and capital leasing, and outhosting itself round of the list of some of the CIO's more common outsourcing management opportunities.

At some point in time, the outsourcing relationship might come to an end and then the question becomes: how is the outsourcing relationship wrapped up? If the contract has a clear end-point, then that end-point is a marker of anticipated success! On the other hand, the partnership might continue with new projects or other projects already underway or through statements of work (SOWs) that extend the original contract—situations when "finished" becomes hard to define.

When making the decision to "end" the outsourcing contract and/or agreement it is nearly always advantageous to leave some door open to a later re-start or even a continuation. The contract itself may have post development aspects such as ongoing maintenance, incremental enhancements, up-leveling of hardware and software, and training to name just a few. Once a good relationship has been established and tested through a real project, keep it active and productive whenever possible.

There is, of course, the darker side of ending an outsourcing relationship— not knowing when the party is over. When dealing with unrefrigerated fish or visiting in-laws, there comes a time when it's time to part ways. It is important to build all agreements with the appropriate clauses to ensure that if the relationship gets to the point where it cannot be salvaged, then you can reasonably extricate yourself from the contract. (You are, after all, the customer.) The earlier such relationships are terminated the less traumatic it will be for both parties. With good planning, evaluation, and execution by the outsourcee and the outsourcer both can realize a satisfactory and mutually acceptable outcome.

Is outsourcing Nirvana achievable—forming marital bliss between two entirely separate companies in one of the many forms of relationship discussedin this chapter? Yes, and like anything worth having (or achieving) it does not come without a lot of careful, objective scrutiny and planning. Careful planning, evaluation, selection, contract creation and agreement, and shared goals are critical to the success.

Leo Tolstoy captured the essence of successful and unsuccessful outsourcing relationships in his novel, Anna Karenina: "Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way." Think of all the many essentials that a man and a woman must harmonize to make a successful marriage after choosing to live together: how to spend money, howto spend free time, religious beliefs, mothers-in-law, how to reach compromise, where to live, selection of mutual friends, number of children, methods of discipline for the children, pets or no pets, practicing a faith, setting up a budget, sticking to a budget, where to take vacations, and closet space to name a few.

Now think of the same set of harmonized requirements necessary for a successful outsourcing relationship. Here is Tolstoy's point: when a marriage or any other complex relationship succeeds, the participants find a way to make all the essential requirements work—all successful relationships are alike in this way. When a complex relationship fails, it is because any one of a number of different combinations of the essential challenges cannot be met to the satisfaction of one or all participants—all unsuccessful relationships differ in terms of the unique combination of one or more failures to harmonize.

Exhibit 7.11 is a summary and reminder of the key planning phases that need to be harmonized to establish a successful outsourcing relationship. With globalization moving from assertion to reality, there has been no better time to engage an outsourcing relationship. Take the time to find the right match.

<Company Name> is adding to our development capabilities by engaging an offshore outsourcing partner. We expect this to be a long-term partnership.

<Company Name>—a <industry/product type> market leader—combinesworld-class innovation and industry experience, enabling people to <what's done>. <More about the company and its customers or the IT group and its customers.>

We are on a very tight schedule and plan to make a decision by the end of April. Please indicate your level of interest and qualifications by completing the attached spreadsheet. It includes a company information sheet, a qualification sheet, and an RFP analysis criteria sheet (this one is for your information only). Following is the schedule for the RFI:

April 2: Return completed spreadsheet via e-mail

Week of April 5: Face-to-face meetings will be scheduled with qualified potential partners at which time you and your team can present your qualifications and meet us

April 14: <Company Name> to select the top 3-5 qualified finalistsfor NDA and Request for Proposal (RFP)

April 16: <Company Name> will notify the qualified finalists and forward NDA for signature

When we move to the RFP phase, we will disclose the specific projects, requirements, and time lines. Qualified finalists will have two weeks to respond to the RFP with their proposal. By the end of the first week, any questions must be submitted in writing (via e-mail), and a teleconference will be scheduled to walk through these questions. Following the teleconference, the finalists have one week to submit their quote. Our ultimate selection will be based on the following criteria:

Relevant technical capability and relevant skills availability

Quality, infrastructure, and management processes

Commitment to <Company Name>

Company viability

Cost

We look forward to receiving your response to the attached RFI by April 2nd. If you have any questions prior to that time, please do not hesitate to call or e-mail me.

<CIO's name>

Dear <Potential Partner Company Representative's name>:

We are pleased to advise you that <Potential Partner Company name> has moved to the second round of our investigations. We would like to schedule a meeting to have you present more information on <Potential Partner Company name> and to discuss your capabilities. Please contact me at your earliest convenience to schedule a date and time that you are available to come to <your city>. I look forward to hearing from you.

Regards,

<RFI Coordinator's Name>

Dear < Potential Partner Company Representative's name >:

Here is the proposed agenda for our meeting. Please advise if you have any requested changes.

Introductions & Agenda Review —All

RFI response presentation —< Potential Partner Company >

Concentration on areas relevant to <your company>

Experience Type #1

Experience Type #2

Experience Type #n

Availability to begin within next 30-45 days with experienced personnel

Concentration on areas relevant to <your company's size and type>

Experience with <your company's size and type>

Development process with <your company's size and type>

Business process with <your company's size and type>

Applicable references who can be contacted

Feedback

—<Your Company>

Next Steps —All

—All

Please let us know who (name and responsibility or role) from your company will be participating in this meeting. We prefer that your key <your country>-based participants attend in-person.

Regards,

<RFI Coordinator's Name>

Dear <Potential Partner Representative's name>

Attached is the <your enterprise name> Request for Proposal (RFP). The schedule for the RFP is noted on page 2. Also, attached are FAQs in response to queries, the specification for the project, and additional background information on our existing environment. The timeline for our RFP process appears below. We look forward to your response.

RFP issued:Wednesday, April 21

Questions of <your company> related to the RFP: due by close of business, Monday, April 26

Questions made generic, consolidated, and distributed as FAQ: Wednesday, April 28

RFP response: Due by close of business, Monday, May 3

RFP reviews by <your company>: Completed by Wednesday, May 5

Follow-up questions by <your company >: Completed by close of business Friday, May 7

On-site (<outsourcee city, outsourcee country>) Visits by <your company >:Week of May 10

Final selection: notification on or before Friday, May 21

Final negotiations: May 21-30

Project start:Week of May 31

First full project deliverable for production use: Friday, July 30

Would you please send me the address and other appropriate contact information for the proposed visit to your facilities in <city, country> for he week of <date>? We are scheduling this trip.

Regards,

<RFP Coordinator's Name>

I Section 1: Introduction and Scope

Introduction

Invitation to bid for the RFP and the RFP timeline [Appendix 7.D]

A brief paragraph about <your company>

Scope of Proposal

If the proposal could develop into more phases than the one in the RFP, this is the place to so indicate.

The follow-on phases are included to get "order of magnitude" timing and pricing and to indicate interest in additional work if the first phase proves successful.

Outsourcing Partner Requirements and Skills

This section describes what is expected of the outsourcing partner and what <your company> will contribute by Phase.

This section should include a general list of requirements for partnership. Use them to clarify an intent for a long-term partnership and how important these are to the partnership being a success:

Successful experiences, with references, working with <companies of your size and type>

Willingness and ability to adapt to <your company's> developmentand production processes as deemed appropriate by <your company>

Acceptance of a <your country>-based presence

Immediate ability of on-board skilled resources

Immediate availability of appropriate development, integration, test, and maintenance facilities and resources including those required for <your software environment and hardware environment>

Certification through appropriate ISO and SEI-CMM bodies

Willingness and ability to proceed on the projected schedule

Completeness, accuracy, and openness of information related to the project(s) status

Fluent, regular, and as-needed communications as soon as questions, problems, needs arise

Contract Schedule and Terms

Repeat the phase schedule

Intent is a long-term relationship and the pricing should reflect it

Establish post-delivery maintenance expectations:

Response times to problems that arise

Rates quoted on a time and materials basis should be quoted on a person-week basis including customary work week of the location and any holiday and weekend work as needed including 24 × 7 coverage (if needed) and a Not-to-Exceed (NTE) component tied to negotiated, mutually acceptable erformance criteria

Rates quoted on a fixed-price basis should be quoted on the assumption of a payment on a regular monthly or quarterlybasis tied to negotiated, mutually acceptable performance criteria

II Section 2: Requirements and Specifications

Support Requirements

Support is negotiated during the contract negotiations; however, expectations should be set here. For example:

24-hour turn around time for any e-mail correspondence

Weekly status and outlook call

Weekly status and outlook report distributed via e-mail

Monthly senior management status review and outlook including trend analysis

Quarterly senior management review including dashboard analyses

Documentation Requirements

Documentation requirements and expectations are set here; for example for a full end-to-end project:

Phase "n" Project Overview and Architectural Specifications

Phase "n" Design Overview and Design Specifications

Phase "n" Development Plan

Phase "n" Documents and Publications (Internal and External) Plan

Phase "n" Quality Assurance and Test Plan

Phase "n" Release to <manufacturing, production, customer, etc.> Plan

Phase "n" Acceptance Criteria (jointly negotiated with <your company>)

Phase "n" Maintenance, Service, and Support Plan

Framework for Phase "n" Follow-On Plan (including all the above)

Technology and Knowledge Transfer Plan

Hardware Requirements

Who supplies what hardware to work on the project

Expectations should be set such that the potential partner must identify what hardware is required that <your company> must supply for development and for ongoing maintenance

Expectations of what hardware the potential partner is expected to supply on their own must also be set

For hardware supplied by the potential partner, clearly stipulating who pays for it and how it is paid for is required.

Software Requirements

Same general stipulations for the hardware requirements

<Your company> is expected to provide a list of known required software

Project Management Requirements

Expectations <your company> has on the potential partner; for example:

24-hour turnaround time for any e-mail correspondence

Weekly status and outlook call

Weekly status and outlook report distributed via e-mail

Monthly senior management status review and outlook including trend analysis

Quarterly senior management review including dashboard analyses

Set the expectation that unless via prior agreement, it is expected that project management billings will include these updates and will not exceed "n" hours per week billed to the project.

III Section 3: Qualifications

Qualifications

Set the expectation that because you are planning a long-term relationship and mutual success that you have requirements for how the project is staffed; for example:

Qualified, consistent, and stable non-rotating team is applied to <your company's> projects

Project members with a minimum of a 4-year technical degree from an accredited university

Project members to have the appropriate skills noted earlier for each Phase during development and appropriate afterwards for subsequent maintenance, service, support, and enhancements.

Program manager/Project manager must have skills and experience in managing projects of a similar nature to each of the phases.

Experience must be verified via certification program and/or customer reference.

The expectation should be set that <your company> will be fielding a highly qualified, experienced, professional, and motivated team to work with their equivalent.

IV Section 4: Pricing and Evaluation

Pricing and Payment Terms

Establish that all pricing and payments terms need to be in <your country's currency>.

Reiterate that with a long-term relationship being desirable that pricing should be reflected in pricing that is aggressive.

Reiterate the "time and materials" and "fixed-price" quotes basis.

Define the basic planned payment terms based on measurable deliverable and milestone achievement; for example:

The first 25% installment will be made at the time of official project start

The second installment of 25% will be made following <your company>'s acceptance of a negotiated, mutually accepted technical development checkpoint

The third and final installments of 50% will be paid no later than 60 days after final acceptance by <your company> and turn-over of the completed work whichever is later.

Reiterate the post-turnover service and support expectations

Evaluation Criteria

Define the evaluation criteria to be used on the RFP responses; for example:

Using the evaluation criteria under "Analysis Criteria" in the RFI spreadsheet

Experience and availability of experienced and skilled professionals in the areas defined as required

Experience and availability of experienced and skilled personnel and project management resources

Applicable references

On-site visit validation and verification

Project and On-Going Cost Projections

Specify that from the RFP analyses two potential partners will be chosen with whom to negotiate to a final agreement and when the two will be notified.

Identify when the final negotiations must conclude and when the award will be made.

Reiterate the project start date.

V Section 5: General Information

Deadlines

Reiterate the RFP deadlines from the earlier section.

Proposal Contents

Reiterate the date by close of business the RFP response is due.

Reiterate the minimally acceptable information required for the response to be accepted; for example:

Corporate Information as listed in the RFI spreadsheet

Phase 1 Development Quotation

Prices, costs, terms, and conditions

Quantities of hardware and software and accessories required rom <your company>

Resource, Task, and Deliverables Timeline

Incentives, and penalties proposal

Phase 1 On-Going Maintenance, Service & Support, Incremental Enhancements

Prices, costs, terms, & conditions

Quantity of hardware, software, and accessories required from <your company>

Resource, Task, and Deliverables Timeline

Incentives and penalties proposal

Phase 1 defined resources and credentials

Phase 2 Level of Effort Estimate and Timeline (non-binding)

Phase 3 Level of Effort Estimate and Timeline (non-binding)

Reiterate that the RFP response must be approved and authorized by the appropriate Corporate Executive of the potential partner.

Reiterate that all costs are to be in <your country's currency>.

Non-Disclosure Agreements

Reiterate that the subject and the work are and will continue to be bound by confidentiality agreements.

Intellectual Property Rights

State the expectations about who owns intellectual property, architecture, designs, and product components, source code, and results developed as part of the agreement.

Defines the above terms.

Publicity

Establish that all companies submitting responses to the RFP agree by doing so that the proposal nor any subsequent agreement or lack of ability to reach an agreement be publicized or be confirmed or denied publicly without the prior express written approval of <your company>.

This also includes using photographs, video recordings, or <your company>'s name without prior express written approval.

Contact Information

Provide the RFP Coordinator's name and contact information.

Reiterate the RFP questions date and the submission date.

Dear <Potential Partner Representative's name>:

We would like to arrange to meet with your team at the site where the work would be done in <potential partner representative's city, country> beginning the morning of <proposed date>.

We would like to achieve the following objectives during our visit:

Meet your key management team to establish a relationship with them.

View your facility and resources (systems, communication infrastructure, hardware, backup systems, etc.).

Meet people on your team (program managers, architects, developers, test engineers) who have experience in the type of projects we have identified through the RFI and RFP.

Provide you an opportunity to showcase your technical capabilities in relevant technologies and highlight successful projects of a similar nature.

Understand the cost basis for your RFP response.

Understand your human resources and training competencies and practices that help reduce attrition and building best-in-breed teams.

Understand your delivery model and quality management systems to assure timely delivery of projects while meeting the highest levels of quality.

Please refer to the attached agenda and feel free to suggest any other points that you would like to address during our visit. We are planning for the visit to be 4-5 hours; however, if deemed appropriate we can dedicate an entire day. Let us know your preference.

If you have recommendations on who to contact for hotel and transportation arrangements we would appreciate knowing.

We look forward to hearing from you and to our visit.

Best regards,

<Your company's site visit coordinator's name (or your name)>

SAMPLE AGENDA FOR SITE VISIT

Time | Agenda | Lead |

|---|---|---|

0900 | Pick up from hotel and proceed to <their company & location> | |

0930-0945 | Introductions and Review of Visit Agenda | Partner Representative |

Session 1 | ||

0945-1015 | Presentation: <Your Company> Visit Objectives | <You> |

1015-1045 | Presentation: <Their Company> Corporate Overview | Senior Manager |

1045-1130 | Presentation: <Their appropriate type> Practice | Practice Head |

Session 2 | ||

1130-1200 | Presentation: Human Resources Development and Training | HR Senior Manager |

1200-1230 | Presentation: Information Protection Policy | IP Head |

Session 3 | ||

1230-1300 | Presentation: Quality Processes and Best Practices | Quality Head |

Session 4 | ||

1300-1400 | Proceed for Lunch with Project Team | All |

1400-1500 | Presentation on <specific project related to <your company's project> | Development Mgr & Lead |

1500-1515 | Tea Break | |

1515-1630 | Travel to Lab and Walk-through Lab Tour | Lab Head |

1630-1700 | Wrap-up and Next Steps | All |

[67] http://m-w.com/cgibin/dictionary?book=Dictionary&va=outsourcing&x=15&y=16

[68] Adapted from "The Perfect Pursuit of Platform—Trend 8: Outsourcing Will Get Bigger, But Not More Critical," accessed at http://www.cioinsight.com/article2/0, 1540, 1909298, 00.asp, December 15, 2005.

[69] Adapted from "The Perfect Pursuit of Platform—Trend 8: Outsourcing Will Get Bigger, But Not More Critical," accessed at http://www.cioinsight.com/article2/0, 1540, 1909298, 00.asp, December 15, 2005.

[70] There is a notable reduction (five absolute percentage points) in help desk/ end-user support investments.

[71] Adapted from "The Perfect Pursuit of Platform—Trend 8: Outsourcing Will GetBigger, But Not More Critical," accessed at http://www.cioinsight.com/article2/0, 1540, 1909298, 00.asp, December 15, 2005.

[72] Karl D. Schubert, The CIO Survival Guide:The Roles and Responsibilities of the Chief Information Officer (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2004) 16-17, 218-220.

[73] See note 5 above.

[74] Gary Hamel, "The Why, What, and How of Management Innovation" Harvard Business Review 84 no. 2 (Feb 1 2006): 80.

[75] Adapted from Djavanshir, G.R., "Surveying the Risks and Benefits of IT Outsourcing," IT Professional 7, no. 6 (Nov-Dec, 2005): 33.

[76] John Valente is the Senior Executive of Global Technical Architecture for Best Buy and is in the unique position to speak with some authority on this issue. He designed Best Buy's outsourcing structure and then joined Accenture to lead the execution of the structure and plan he designed for their company. Formerly, John was a vice president of new technology development for Dell IT. In both positions, he reports/reported to the CIO.

[77] Mark D. Minevich and Frank-Jürgen Richter, "The Global Outsourcing Report: Opportunities, Costs and Risks," CIO Insight, December 15, 2005: 55-56.