ROI: Does It Make Sense?

The opportunity is present, the plan is in place, you have access to capital, and you can assemble the right team. Should you go ahead full tilt? You need to step back and evaluate the overall project. Does going forward make sense in the context of corporate goals, IRR of cash flow, the organizational balance sheet, and the cost of capital? Eventually all this must be rationalized in the go/no-go decision. In many cases, this also engages the BOD and the governance model of the organization and project decision processes. This chapter will give you a method for deciding whether to pull the trigger—or not.

We now know that there are multiple influences in the decision processes surrounding technology commercialization. The importance of market-driven needs, creativity and innovation, solid organizational models that are nimble and adaptive, and the planning details and performance monitoring are important for sure. Capital plays a critical role as the projects will need it to go forward. It is the fuel that drives the engine. It can be metered out in lean fashion or significant resources can be brought to bear.

There are multiple sources of capital that range from internal corporate funding to formal investment capital led by angel and venture capital groups to public funding. Each has its own nuances in their priorities, decision-making processes and, of course, influence on the outcomes. Let’s first look at some of the alternatives and their investment goals. They fall into three broad categories.

Early Stage Capital

Particular to the formation and early stage standalone companies are three subcategories. The first is sometimes referred to as FFF (Friends, Family, and Fools). The Fools aspect deals with investment made well before the project is considered an investible entity. These investments are made on an intuitive or emotional basis rather than one subjected to critical and professional review. Being early in the investment cycle it also requires enormous returns to compensate for the time of the investments. A variation of this are projects that are self-funded or “boot strapped.” This type of entity has the freedom of not being subjected to the onerous Terms and Conditions of more formal rounds. If a project is capital-intensive, this form of investment becomes limited by how “deep the pockets” of the entrepreneur are. The structure of these deals is also more informal and may even be fulfilled by simple partnerships.

The next category of early stage capital infusion deals with more structured investments characterized by angel and venture capital. Angel capital as a source was identified almost 40 years ago by Professor Bill Wetzel at the University of New Hampshire. Bill was interested in how wealthy individuals living in New Hampshire were investing in early stage ventures as individuals. He noted how much more effective they would be if they worked as groups. Many of the individuals were quite independent and not interested in this. Today this category of investors have grown and have a national “trade” association called the Angel Capital Association (ACA), which is comprised of 187 chapters across the United States. There are 32 in New England alone.1 They meet in national and regional sessions to discuss trends, best practices, and even have managed to consolidate deals into projects. Angel investors invest their own funds (even if grouped on separate LLC arraignments). Returns are measured on individual portfolio base. Their motivations to invest are broad and include the need to “give back,” as well as harder investment metrics.

The mechanics of an angel meeting is interesting to note as it gives us insight into the investment-decision process. Angel investing has emerged from an individualistic single-person decision. As the potential project stream increased from the early Wetzel observations, more disciplined approaches emerged. Membership in angel groups is varied but sometimes the groups form a “personality” about which type of deals they favor in terms of sector, size of investment, and stage of growth. An example is Common Angels in Boston. Their focus is on “software, Internet, digital media, and cloud, from Seed to Series A.”2 Disregarding this opening preamble wastes time and effort and sets up a rejection that is not based on the merits of the project. A rejection is a serious issue as it propagates thought the investor community.

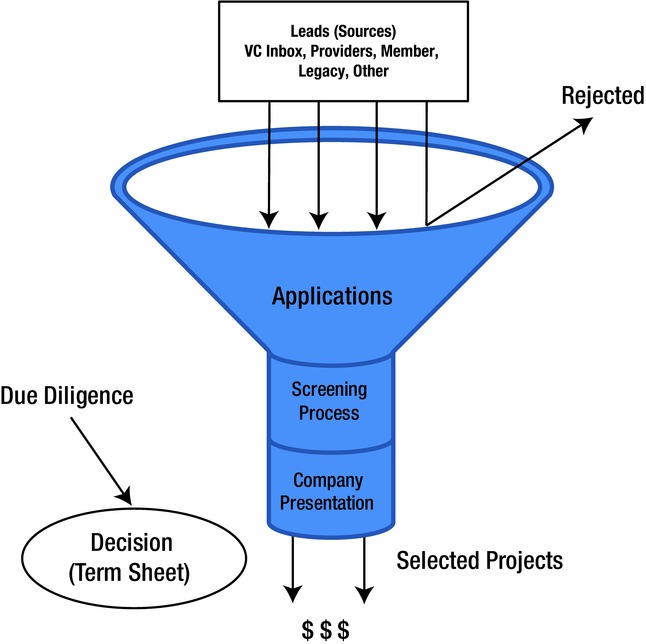

Active angel groups have memberships numbering 50 to 75. This number allows independent internal committee structures to evolve. An example is the screening committee whose role is to pare down approximately 20 projects a group receives in one month to the one or two they will act on in an open presentation. The committee screen focuses on their merits as a potential investment and the fit to the group’s interests. A strong priority is shown to referrals. If a member or known service providers have been identified as the source of the lead, it has screening priority. Most groups have provided Internet-level information for the first encounter. Beyond the political implications of this, I suspect that it also validates the alignment of the deal to the group’s values. This duality is shown in Figure 10-1.

Figure 10-1. Traditional angel funnel

As a given project negotiates successfully through the screening process, it is presented to the general membership in a somewhat formal (usually organized at PowerPoint level) presentation. Group meetings are typically scheduled on a monthly basis. The presentation is characterized by an individual investor stating his or her investment interests. “I’m in” is a typical phrase. An awkward silence is an alternative. Those of you who have seen the Shark Tank show on ABC may recognize the sentiment. If a sufficient number of individuals buy in (remember it is an individual decision in angel investing), the project moves to a due diligence committee process.

“Due diligence” is the process of investigating the material facts and what attorneys call the Representations and Warranties of a given project. The process has its roots in the U.S. Securities Act of 1933, whereby stock brokers were required to check the material information with respect to selling stock. It was particularly aimed at potential investors who may have lacked sufficient information about the risk elements of a particular investment. There is an international equivalent in the Foreign Corrupt Practice Act (FCPA). With the trend toward increased global commerce, this provision becomes even more relevant.

Upon completion of the investigation, a formal (usually written) report, complete with recommendations, is submitted to the general membership. An important element of the report is a proposed outline for the Term Sheet that accompanies the group’s proposal to the presenter. This document sets the basic parameters of the offering. It is a formality of a succession of documents, including the Letters of Intent (LOI) and Memoranda of Understanding (MOU). They set the intention of the deal with an outline and future commitment to settle the details. The National Venture Capital Association (NVCA) maintains a catalog of common deal document templates on their web page (see www.NVCA.org), including common Equity Term Sheet elements. They include:

- Amount to be raised and the timing of the closing transaction.

- Price per share, which is the intersection of money and equity. In many ways, this is the heart of perceived value of the project in both current and long-term (3–5 years) timelines. Sometimes it is expressed in a percentage of the total equity (ownership) of the company. It is a swap of common shares for money. There is significant misunderstanding about owning 50% or less and control of the company. If an investor issue relies on the financial positioning of the players, it suggests that there are much more significant issues. Later in the Term Sheet, more onerous control and reporting issues are defined. The argument of whether you would want to own 10% of a sufficiently well-funded and ongoing enterprise or 90% of floundering one is quite obvious. Recognized value and the ensuing wealth creation depend on the number of shares owned as well as their perceived value. If all that weren’t complex enough, there are various classes of stock ownership such as “preferred shares,” whereby the owners have both liquidation preferences and preferred voting positions.

- Among the preferences enjoyed by the investors as preferred shareholders is one called the “Liquidation Preference.” This is a diabolical tool invented to ensure that investors can “cash out” of a deal first. It goes something like this. If a company raised $10 million of venture money for 30% of the company’s equity and the company is sold for $25 million, the investors should realize $7.5 million if distributed on a prorated basis. Under the liquidation preference provision, they would receive $10 million. This is called a 1X liquidating preference. If the multiplier were 2.5, they would receive the full $25 million—yikes! In the March 8, 2014 issue of Business Insider, author Nicholas Carlson called this a “horror show.” I think his characterization is an understatement, but the concept of liquidation preference seems non-negotiable in the world of investment capital. Regarding an investor as a partner in the deal also seems a stretch.

- There are other provisions of a Term Sheet such as anti-dilution formulas that protect the investors in the likely case where additional stock has to be issued to raise subsequent rounds of capital. There are voting rights in decisions regarding selling the company and even raising of additional capital. These are generally referred to “Registration Rights,” whereby under the Rule 144 of the Securities act of 1933, investor shares can be “registered” in a manner that allows them to be sold publicly. In effect, it allows the investors to sell the company at their preference—yikes again! In addition there are participation rights that give them voting seats on the board of directors and rights to terminate the CEO’s employment.

- The NVCA template cited previously suggests that Term Sheets are somewhat “boilerplate” in their content and format. This is probably somewhat true. But it also suggests that the crafting of the terms is clearly in the domain of corporate attorneys. It also suggests that the terms are somewhat lopsided in their definition in favor of the investors. Solid management performance and the meeting of goals and schedules make it an act of absurdity for the investors to capriciously act to invoke the onerous provisions.

With the Term Sheet proposal secured, an offer is assembled for the presenter. A period of negotiation about the terms and price per share follows. In addition, the details and plan of action to go forward are ironed out. Another interesting aspect is that angel investors must declare that they are accredited investors. Under the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Regulation D, an accredited investor is one who has an income of $200,000 and a net worth exceeding $1,000,000. Its intent is to ensure that the investor is both sophisticated enough and substantial enough to make high-risk investments. There are initiatives such as the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 that try to exclude the primary residences in the $1,000,000 calculation and Government Accounting Office (GAO) attempt to raise the require to $2.5 million and the current income to $300,000. These proposals would help limit unqualified risk, but also limit the number of potential investors.

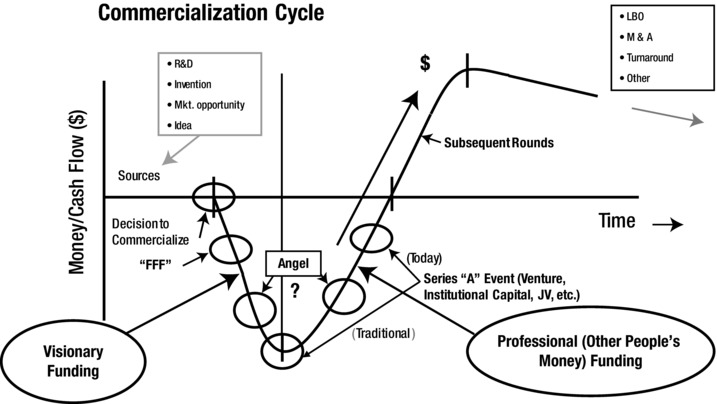

One significant aspect of this step is the selection of a lead designated board member. This person not only sits on the board, but also carries the voice of the investor group. This aspect of the investor membership also carries the responsibility of reporting back to the investor group. The formality of the process varies with size and with the history of the investment portfolio. To further amplify this process, it’s fruitful to compare the angel investing process to the more formal role of the venture capitalist. To gain a perspective of this comparison, see Figure 10-2.

Figure 10-2. Commercialization cycle

Institutional Investing, the Venture Business

In 1945, Georges Doriot (later coined the “father of venture capital”) founded the first venture capital firm in the United States in Boston. It was called American Research and Development) in a text entitled “Creative Capital: Georges Doriot and the Birth of Venture Capital”3 and was co-founded by Karl Compton (former president of MIT) and Ralph Flanders, a businessman. What distinguished his investments was that they were made with other people’s (limited partners) money under his control. This idea was validated by an investment of $75,000 he made in Digital Equipment Corporation in 1957. The stock was liquidated by an initial public offering in 1968 at $355 million. That was an IRR of 101%. From these beginnings, a new industry of venture capital with centers in Silicon Valley California and Boston was spawned. Doriot was born in Paris and came to America to attend the Harvard Business School, where he later became a professor. He was also known for his pithy quotes. One of my favorites is, “Without actions, the world would just be an idea.” He also preached that the expanded role of investments should be one of “nurturing” the projects beyond just the financial mechanics. Unfortunately, this secondary role has shifted from focus in the modern incarnations of venture capital industry. It has become transaction-oriented.

Comparisons

Within the categories of angel and venture capital funding are the primary sources of capital for early stage, standalone, ventures. Although they both focus on early stage projects, the differences are significant. An obvious starting point is that the sources of capital are quite different. Angel funding is private money belonging to the investors. Typically it derives from cash out of a previous venture and controlled by the individuals making the investment. This is significant because it allows a much broader agenda for the decision process. I was the co-founder of the Cherrystone Angels in Providence, Rhode Island. In that fund we became so interested in the “other” aspects of the decisions that we actually surveyed the membership at each investment as to why they made the specific investment beyond ROI considerations.

The results were intriguing and ranged from some who “wanted to give back” to helping economic growth in Rhode Island. Sometimes this secondary “agenda” is useful to motivate individual investors to serve as mentors and even get their possible board participation in the new ventures. Sometimes their participation is more tactical and includes industry contacts and customer introductions. The formal investments/equity interactions between angel and venture investors are somewhat similar, as they both employ similar Term Sheets as part of their investment packages.

There is a minority view that the angel groups benefit from maintaining “side car” funds managed by the leadership of the group. In theory, this structure allows subsequent funding to be applied that is independent of the fluctuations of individual investment decision processes and is closer to the funding need dynamics of the project.

There is now a brokerage of sidecar funds established by SideCarAngels.com. It was founded by Rick Lucash of Launchpad Angels and Jeff Stoler. Common Angels, Houston Angels, and Golden Seeds Angels are cited by the Kauffman Foundation-funded Angel Resource Institute as examples of angel groups that have these funds. The management of the funds is a different dynamic than individual decisions and closer to the managed funds of venture capital. The hybrid is touted as being effective but there is not sufficient data to support their overall effectiveness in the investment cycle. Anecdotal data from the Angel Resource Institute4 suggests that about 20% of all angel groups have these sidecar structures.

Venture capital is more structured than angel involvement and tends to appear later in the lifecycle of new ventures. “Funds” within venture groups are created based on proposals to groups of limited partners. Pension funds that require small parts of their portfolio to be invested in high-risk/high-growth help boost their overall portfolio performance. The Employment Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) set the stage for pension fund involvement. The California Public Employees Retirement System is a good example. The 1970s also saw the inception of some of the larger firms that became thought leaders in the industry. Kleiner Perkins in Silicon Valley, California and Greylock in Boston are examples of these firms. In addition the National Venture Capital Association (NVCA) was formed in 1974. It became the ultimate source of information and dissemination of information about best practices for participating firms.

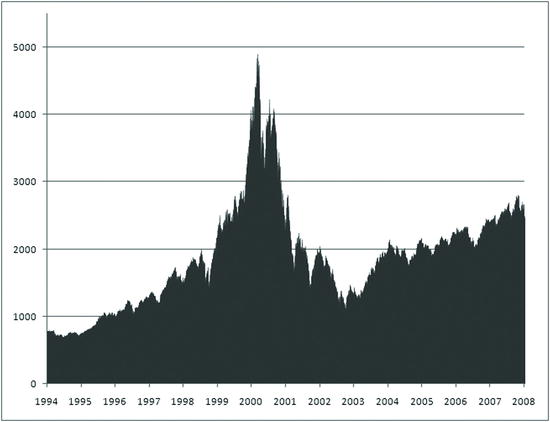

Venture funding became a “growth industry” for almost 40 years until March 2000, which is when the infamous “dot com” collapse occurred. Too many deals were focused on soft metrics such as “eye contact” and “stickiness.” Attention to longer-term value propositions slipped from focus. The investment deals faltered and the result was a major meltdown of funds’ values. The impact of this was that going forward, venture fund attention and investment priority was given to less risky and more mature deals.

An example is the computer disk drive industry. In the 1970s, there were 35 domestic manufacturing firms funded by the venture capital industry.5 Four of them could supply the world’s need for product. Today, there are four major suppliers. The others failed, merged, or simply fell by the wayside. Clayton Christensen, cited in Chapter 1, had a more severe view. It was that the industry, fueled by venture capital, simply couldn’t adapt to technological change fast enough. Whatever reasons are assigned, it is clear that there was simply too much money chasing bad deals at that time.

In the lifecycle model, there is a blurring between the role of the venture industry and the role of investment banking. The venture firms retreated from early stage deals as a reaction to the failures of the “dot-com” companies and left behind the funding needs of the early stage deals.

If the angel industry had not grown to replace early stage funding, one ponders about where the funds for new, high-growth potential projects would come from. The dramatic impact of the “dot com” portfolio model is shown in Figure 10-3. It is a graphic of NASDAQ Composite Index, which is technology stock laden. It presents the rapid gain and loss of the value of their stocks. Of more significance is the strategic change in venture funding that occurred. It favored later-stage deals that embraced less risk.

Figure 10-3. Venture investment “dot com” bubble and its collapse

With its 1.6 million person membership, 1-2% of its assets invested in this category are a small percentage, but a significant amount of funds. Typically there are multiple funds under management at any one time. The implications of the multiple fund models are that there are liquidations requirements of 5-7 years of the individual funds created that drive the timing of the liquidation events. Probably more significant is that the funds are managed by professional teams rather than the previously defined individual angel decisions. The team members tend to have sector area experience and may have even been in executive leadership positions in a given industry.

The focus is on the ROI components as they are the basis for the limited partner participation. Fee structures for these transactions are so insidious that individual partners are rewarded with a “carried interest fee” of several percent of the invested capital they place in deals. This fee has certain limitations in that the original amount must be returned and certain return “hurtle” rates must be maintained. The term of “carried interest” is derived from 16th Century shipping, whereby ships captains were given 20% of the profits for carrying certain products. Today it is meant to be an incentive to allow risk-based investments decisions. They are indeed an additional financial burden on the outcome of the investment.

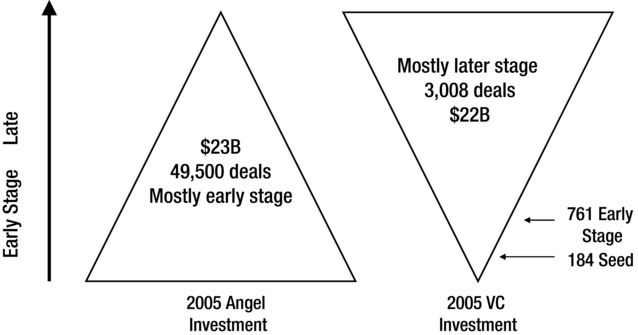

There are clearly differences in those primary sources of investment capital. Today, each has its place in the lifecycle of the company or project. In the earlier days of the 1960s both seem to be converged on the startup. Venture capital went through a strategic shift after the much touted “dot come” bubble burst and there were tremendous loses and pullback. Today, venture capital that utilizes other people’s money seems more risk adverse but is capable of more money per deal. Angel decisions are individual and can appear earlier in the cycle. What is important is that the relative positions and decision metrics are understood. Another view of this is shown in Figure 10-4.

Figure 10-4. Convergence of venture and angel deals

The vetting process of the venture firms is not that different from the angel process and resembles a funnel model. A significant difference is the presence of a formal investment committee. Usually attended by general and senior partners in the firm, they are the equivalent of a general meeting of the angel firms. They have a charter of ensuring alignment of the funds’ investments to the agreement secured with the limited partners who have supplied the funds upon which they operate. The difference is that this decision revolves about “other people’s” money and the angel decisions are made on a personal (individual) level. That aspect separates the venture capital decision process from the intuitive aspect of angel decisions.

It is important to note that the angel deals tend to be earlier in the lifecycle, thus they require more subjective decisions as there simply isn’t enough factual and operating information to support the decision process. Today the venture folks have moved to more substantive deals that occur later in the cycle. The implications of this are that they must also envision strategy of an exit to public equity markets and/or merger activity. The terms structure actually envisions such an exit and sets the rules for that later decision process. All this implies an orderly process of investment vehicles. In reality there are also venture fund that are referred to as “boutique” and focus on earlier stage deals in specific and narrow segments. Certain industries such as the medical products and biotech require longer and larger investments. They depend on specific industry venture firms earlier.

The Broader Resources

According to the NVCA (www.NVCA.org), venture backed deals accounted for 11% of private sector jobs and 21% of the GDP. Formal early stage capital is an important segment of the formation of new companies and ventures. However, it is not the entire landscape. In a personal tally, I identified over 20 sources of funding that ranged from personal credit cards to public, non-dilutive grants and foundation support Let’s look at two of the these large areas.

The first category is one of non-dilutive infusions of capital. The term drives from the fact that money is brought to the project or new venture without an accompanying transfer of capital. In that sense it is quite attractive. On the other side, there is usually a deliverable of written reports, procedural changes, or a working prototype model. There is enormous freedom of choice that accompanies equity-based funding; maybe not so in the world of grants and alternative funding. Something about the saying that “there is no free lunch” seems to apply.

Certain fields use government funds such as National Science Foundation (NSF) grants in bio tech and basic science and in for forms of R&D funding. Fundamental research in medical and biological fields is so intense that an aggregated source such as the government can make that level of investment at the basic science level. Large and bold investments are part of certain industries. Yearly automotive changes, for example, require large annual tooling and technology expenditures. That is simply part of the automotive business model.

Certain government grants are particularly focused on commercialization. An example is the use of Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) grants. Specifically focused on commercializing innovation, the SBIR was created in 1982 to help various government agencies secure the technology they needed. The U.S. Department of Defense is the largest grantor and issues over $1 billion annually. The grants are released in phases. Phase I grants are generally $150,000 for six months. Later phases may be over a million dollars. There are variations of SBIR grants called the Small Business Technology Transfer Program (STTR). It requires a partnership between a research institution (minimum of 30% participation) and a firm capable of taking the technology to market.

Philanthropic funding is certainly an important aspect of non-dilutive funding. An example might be The Jimmy Fund, which issues research grants through the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. The science might be developed to find cures. License to industrial partners help the technology find paths to commercial reality.

One attribute of external funding is that it invites collaboration. Many academic or research groups combine resources and apply for grants and share their findings. Nonexclusive licensing models allow specific fields of use to be commercialized by individual applications.

Beyond infusions of capital, there are tax credits, incentives for loan energy offsets, and so on, which allow conservation of operating cash, but cannot necessarily be used for direct growth.

There are technical options in non-funding. An example is the use of “green shoe” issues of more shares than the company has issued. It is an overallotment of shares that can be used before the issuance of public stock (IPO). Certain combinations of debt/equity become attractive, such “mezzanine funding,” whereby a lower form of debt is used that is later converted to equity. Vehicles like this serve to bridge financing rounds and offer the debt option.

There is another broad category of funding options. They might be referred to as “other.” I once did an informal survey of this category and found almost 20 such sources. Included are the use of personal credit cards, mortgages on personal property such as real estate, informal loans or pre-payments from vendors and customers, and business plan competition prizes. The conundrum of this category is that the sources are generally not sufficient to meet the long-term requirements of the project or new ventures. Since time to acquire financial resources is such a precious resource, refocusing to primary, more robust sources is the priority.

With this category is the domain of parent company treasuries. This category is quite internally competitive in terms of demand on the resources. Mandates for ROI and IRR are delivered via internal committee documents and memos. The internal process for utilizing internal resources is controlled by hierarchal models that filter all the way to the board of directors for material or substantial amounts. Significant alternatives for acquiring funds in terms of absorbing debt and even floating stock to achieve the goal are available. It becomes the treasurer’s ultimate “make/buy” decision. Sometime this resource can benefit from funding large capital expenditures such as plant and equipment or even corporate M&A activity such as other entity acquisitions.

At the other end of the spectrum, early stage companies do not possesses the “deep pockets” capability of supporting major capital projects of even those capable of high probabilities of success. In this case, the stage is set for raising capital by more conventional means.

Putting It Together

The purpose of this chapter is not to provide a litany of all possible sources of capital for new or innovative projects. It is rather to accent various sources of capital and offer the reader a perspective on the motives and goals of each type. When an airplane flies en route and encounters fuel starvation, there is an awful silence that emanates from the engine. Pilots are trained to begin procedures that will mitigate the risks associated with running out of fuel. Not so with entrepreneurs, innovators, and the teams that support them. Most assets can be procured. This includes people, technology, and even markets. The end of cash signals the end. In this sense, the airplane/pilot training analogy simply doesn’t hold.

Each source of capital carries its own unique investor decision dynamics, expectations, and responsibilities. Understanding their nuances increases the probability of success in a commercial venture.

Once capital is secured and the project or venture is funded and launched, we will look at a myriad of regulatory and governmental boundaries on the modern corporate model. They are historically unprecedented in terms of the complexity, invasiveness, and demand that they put on management and the enterprise’s resources.

Know Your Market

The challenge of quantifying the attributes and dynamics of the environment affecting the customer’s decision to purchase a product or service is quite important to the eventual success of the commercialization process. It guides the allocation of resources required to accomplish the project’s goals. You need a preliminary market assessment and a plan of action to achieve it. Doing so is often fraught with uncertainty to the point where the process is either done in a perfunctory manner or skipped completely.

One of the first implications of the planning process is how the complete operational chain responsible for producing the product can be engaged. This includes the formal planning process, inventory decisions, procurement strategies, work force expansions/contractions, purchases of capital equipment, plant and promotional activities, and so on. The cash flow implications of resource allocation to these functional areas is significant. The direction for these efforts comes from the market-driven plans that are the defining center of the planning activity.

A significant attribute of market assessment deals with the segmentation dimensions. Like the General Motors example cited previously, the same type of products (automobiles and trucks) can be used to fulfill the needs of multiple demographic and socioeconomic market segment needs. Sometimes the modifications can simply be cosmetic, such as body style changes. Other times they can be more substantive such as drivetrain or accessory kits available within a product line.

It is certainly an easy attribute to measure. The information can be directed to the product design and marketing strategy areas. It also allows the project to seek out profitability and competitive forces and can be chosen to be stable enough to yield positive results. It is common to set up a matrix of the various attributes and use the matrix to define the best path to market by rank-ordering the projects.

An example of this comes from the high-performance semiconductor chip manufacturers. Tooling for a new generation of processors is both expensive and time consuming. Market conditions change faster than this design process allows. Chip designers embed families of features in the chip architecture. As external market and competitive changes occur, they simply enable parts of the product. A subtle benefit of this measurement is that it favors customer retention because it helps identify the characteristics that favor customer loyalty and continued use of the brand name.

Decision Metrics

Management has the ultimate responsibility to decide whether a project (or company) should continue on the path to commercialization. This applies to a startup and to a continuing project within an existing organization. To make a good decision requires the successful implantation of three activities. They include the following.

Goals

In sports there is a clear correlation of specific goals and objectives to winning. There is also a need for rule books (and even judges). In the commercialization context, the projects or companies that are driven by clear and succinct goals that have been well communicated in the organization have a significant advantage over those that don’t. The clarity also improves the decision making about project selection, capital expenditures, and potential profitability. Without clarity of goals or vision, decisions may be made in conflict, or in a suboptimal manner. Sometimes these goals are expressed in financial metrics. Other times they are expressed in market penetration or brand loyalty as expressed in terms of customer loyalty and repeat sales.

Computer-driven data enables us to generate significant amounts of information about markets, finance, and operations. If there ever was a need to explore this, it is in the space of sales and marketing. These functions drive the models and the numerical information helps guide the resources needed to realize them. It would be in terms of advertising expenditures or numbers of sales personnel required to complete the goals. This, in turn, creates a new need for assimilating that data and learning how to make decisions that utilize the information. New tools have emerged that allow better analysis and benchmarking against goals.

A common tool is the “Balanced Scorecard,” created by Dr. Robert Kaplan of the Harvard Business School and David Norton, a WPI-trained management consultant. In their 1996 Harvard Business Review article entitled the “Balanced Scorecard: Translating Strategy into Action,” they stated:

“The Balanced Scorecard retains traditional financial measures. They reflect the story of past events. In an era when investments in long-term capital expenditures and customer relationships were not critical for success. These measures are inadequate for guiding and evaluating information age companies to create future value through investment in customers, suppliers, employees, processes, technology, and innovation.”

The Scorecard utilizes four perspectives that include Learning, Business Practices, Customer Perspective, and Financial Perspective. Of importance is that it looks for changes that delineate learning and growth. These attributes can directly be applied to the marketing function in terms of realized customer satisfaction and market penetration.

Reaching for Decisions

We live in world that has the potential to generate more data and information than ever before. With a mere click of a button we can access sources of information than could never have been imagined in earlier decision formats. Powerful search engines (such as Google) and new data-mining techniques have opened new and possible higher quality data than ever before. In the modern world of global competition and diminishing resources, the search for information reaches all corners of the globe.

With this abundance of data comes a need for a new level of sophistication in our ability to both interpret the data and utilize its information to make decisions. In addition, the rate of change is accelerating, as noted in shorter product lifecycles and nimble market shifts fueled by the Internet and handheld technology. In all of this, first principles as a basis for decision making are even more important than before. Let us look at some of the fundamentals:

- Adherence to the controlling vision. Possibly the most critical element of sound decision making is the comparison to the overall themes or vision of the enterprise in either corporate or project level decisions. It is enhanced in large capital investment issues, where the implications can be multiyear and beyond the lifecycle dynamics of the initial decisions. In product sales, for example, the after-sales margin contribution far exceeds the initial sales transactions. In addition, vision is not a static declaration. It is a dynamic resolution of changing times and markets. The ultimate responsibility to manage the vitality of the vision rests clearly in the dynamic exchange between the CEO and the board of directors.

- Monetary constraints. The “cost of capital” becomes an essential element of the project decision process. In the use of internal funds, there is constant competition. It is rationalized by the Internal Rate of Return (IRR) calculation, which allows the competition of returns between new investments in sustaining a current one. It represents a threshold of return that must be met or exceeded. External funding costs are controlled by interest rates for debt and the balance sheet impact of equity financing. Within those variables is the impact of sectors or market positrons. It requires an enormous amount of capital to create a new steel mill as compared to an Internet software enterprise. This sometimes forces a bias toward lower capital projects, with all the implications of that trend.

- Human resource considerations. All too common is the litany of cases that fail because of the team allocated to market success. The care of defining the required skillsets as articulated by robust job descriptions probably is larger than other considerations. Finding the right people, motivating them to succeed, and providing the proper resources to enable them to execute their responsibilities are critical.

- Technology/IP. Perhaps one of the more fluid aspects of a project is the status of technology. Most of all, is it mature enough to sustain commercialization? Has it been validated? Are there multiple sources of material and parts and can it be replicated? Is it unique and is it a “platform” that can be extended through multiple product lifecycles? Can it be protected with IP, and if so, how strongly? Correcting any of these issues after a product is launched can be expensive in terms of capital, time, and prestige. Consider the case of government-regulated automotive recalls as an example.

Market and External Competitive Forces

Clearly, decisions to move projects to commercialization don’t take place in a vacuum. They are tempered and motivated by opportunities and by the changing dynamics in the marketplace. Changes in competitive offerings, changing regulatory climates, changing technology, and/or changing global influences are just a few of these forces. Traditional marketing tools such SWOT analysis, potential customer surveys, and general organizational awareness are the best mitigators of these changes.

Decisions and Intervention Based on Improving Overall Performance Against the Goals

Although there seems to be an endless list of influences and changing dynamic conditions surrounding the decision-making process, it is still inherent that a decision to go forward (or not) be made. Historically, statisticians such as Erich Lehmann offered theorems such as the Hodges-Lehmann estimator that try to find a statistical median. Likewise, data-finding tools and Bernoulli’s St Petersburg Theorem try to find non-exceptional data to rationalize these decisions.

Inherent in this text is the premise that best results are realized by adherence to the central goals and/or mission of the organization. This allows coherent utilization of resources and their allocation and increased probability of success. In addition, it allows a dynamic feedback to the vision statement, which will allow it to be current with changing external decisions.

______________________

1www.angelcapitalassociation.org.

3Spencer E. Ante, Harvard Business School Press, 2008.

4www.angelresourceinstitute.org.

5Disk Trend Report, James Porter, 1974.