26The dark underbelly of communication competence: How something good can be bad?

Abstract: This chapter traces the histories of two concepts dark interpersonal communication and communication competence before addressing the interconnected construct, the dark side of communication competence. It is argued that incompetence and darkness are not always synonyms; nor are competence and darkness necessarily always on opposite ends of a continuum. Instead the chapter discusses how competence may align with darkness in very insidious, harmful, but purposeful ways. Dimensions of dark competence are presented that help differentiate dark competence from its kin, dark communication and communication competence, providing the concept with its own theoretical space. The dark underbelly of communication competence not only furthers the theoretical and practical understanding of interpersonal communication skills and dark side scholarship, but also better captures the full essence of what it means to be a skilled communicator. A socio-ecological framework is used as a heuristic tool to approach how dark competence may be holistically examined. The framework helps draws the chapter to a close as future research ideas are proposed.

Keywords: dark side, skills deficit approach, dark competence, bright–dark dialectic, contextual embeddedness, socio-ecological framework, communication competence, dark side of communication

Communication is fundamental to a productive, successful life; it allows humans to achieve goals, connect with others, and resolve their differences. Described as the “fulcrum upon which the levers of social life are maneuvered” (Spitzberg and Cupach 2002: 564), interpersonal skills are fundamental to achieving such successes in life. A significant amount of research has shown a positive relationship between communication competence (also referred to as CC) and mental health (e.g., Segrin et al. 2007) as well as satisfying close relationships (Arroyo and Segrin 2011; Flora and Segrin 1999) and successful cross-cultural interactions (Mackenzie and Wallace 2011).

From an Eastern perspective, communication competence (CC) is an equally important skill although it often takes on different forms. In Korea, for instance, harmony is considered a critical component of communication competence (Yum 2012). According to Yum, empathy, sensitivity, indirectness, being reserved, and transcendality are five characteristics of harmony and, therefore, are considered fundamental to CC in the Korean culture. In a review of the CC literature focused more on a Western point-of-view, Spitzberg and Cupach (2002) noted that correlates of interpersonal skills, such as constructive conflict management, positive affective behavior, and supportive behaviors, are related to relational satisfaction and duration in marriages. These same researchers highlight scholarship indicating that being a skilled communicator is associated with more positive health outcomes, educational and professional achievement, and psychological well-being. In sum, studies consistently find that skilled communication is a core part of functional, relational, and emotional success in life, and of one’s ability to have satisfying and enduring relationships (Western, individualistic view) and functioning well as a member of society (Eastern, collectivistic view) in face-to-face as well as computer mediated interactions (e.g., Spitzberg 2006; Wright et al. 2013).

Incompetent communication, in contrast, is associated with a variety of negative behaviors. According to Spitzberg and Cupach (2002), “people deficient in interpersonal skills may experience a pattern of disturbed relationships that distort normal feedback processes, diminish self-esteem, and create pathways to deviant and risky behavior” (p. 570). Problematic interpersonal behaviors have been found to be associated with particular individual traits, such as introversion, shyness, loneliness, and neuroticism (for a review, see Olson et al. 2012). Moreover, because of their tendency to be highly self-focused or boastful during their interactions, narcissists are perceived as less socially attractive (Vangelisti, Knapp, and Daly 1990). Machiavellians are also considered antisocial because of their use of negative communication behaviors such as aggressiveness and competitiveness (Stewart and Stewart 2006). An incompetent communicator is also one who sometimes resorts to the use of aggression (Olson 2002; Spitzberg 1997). In fact, a skills deficit approach was the focus of Infante, Chandler, and Rudd’s (1989) Communication Skills Deficiency Model of Interpersonal Violence. In essence, being an unskilled communicator is associated with fewer satisfying relationships and more problematic encounters, including interactions involving behaviors as severe as relational violence.

With that said, there is another side to communication competence – one that is different from incompetence but representative of the darker side of human life. For some, communicating competently may mean texting daily expressions of love to a partner, letting the person know he/she is loved. For others, these same acts of expressing love, which are considered positive by many, could be a way of surveilling and ultimately controlling the partner’s actions. The purpose of this chapter is to examine the dark side of competence, not the darkness than can be inherent in incompetence. Such a perspective is important to not only furthering the theoretical and practical understanding of interpersonal communication skills and dark side scholarship, but also to being better able to capture the full essence of what it means to be a skilled communicator. This envisioned reality tries to expose the positive and negative along with the altruistic and the egotistic tendencies involved in relational life. As Spitzberg and Cupach (1998a) noted, The intent is neither to valorize nor demonize the darker aspects of close relationships, but rather, to emphasize the importance of their day-to-day performances in relationships. Only by accepting such processes as integral to relationships can their role be fully understood. (p. x)

To accomplish this goal, it is necessary to first review the basic premises of dark communication, followed by a brief overview of communication competence. Next, the association between the two and a review of the factors associated with dark competence will be examined in more detail. The chapter will end with discussion of future research.

1What is dark interpersonal communication?

In a now foundational chapter, Duck (1994) argued that much of the research on personal relationships had focused on the more positive and optimistic side of relating. For example, much work had been done on love, intimacy, and support, and little on alienation, relational distance, or indifference. When scholars did examine the more “problematic” side of relating, Duck continued, they often did so in a way that presumed the problematic was unusual and mistakes were to be avoided. He argued that,

the relational significance of the unpleasant in the real lives of everyday mortals has been seriously underrepresented in theory and research that [sic] has taken too euphoric and decontextualized a view of the ways in which relational life can be nasty, brutish, and short, certainly insofar as it is practiced. (Duck 1994, 4, emphasis in original)

At the time of Duck’s writing, the “niceness” paradigm was believed to have infiltrated the personal relationship literature. Table 1 includes a list, not meant to be exhaustive but illustrative, of exemplary statements demonstrating the benevolent ideology inherent in close relationship research.

According to Duck and others (e.g., Cupach and Spitzberg 1994), a redress was needed, challenging the assumption that relationships were always nice and the people within them equally so. To create such a paradigmatic shift, scholars needed to broaden the study of close relationships to include both the positive and the negative side of relating, recognizing that healthy patterns could have negative outcomes, negative relating could prompt productive results, and some interactions can be both bright and dark in their structure, function, and outcome. In other words, darkness and negativity were integral parts of relationships, not separate from them, and researchers needed to account for the totality of relating.

Tab. 1: Descriptive statements reflecting benevolent ideology in close relationship research.

| 1.Openness is superior to closedness |

2.Disclosure is expected. |

3.Clarity, directness, and accuracy are better than equivocation, distortion, or deception. |

4.Cooperation is preferred over competition. |

5.Social support is important to people’s overall health. |

6.Communicative, social performances are expected to be smooth, effectively managed encounters. |

| 7.Honesty is preferred over deception. |

Along with Duck, communication scholars, Spitzberg and Cupach have spent the last several decades theorizing and studying the dark side in order to shed light on the hidden, elusive, and secret side of interpersonal and close relationships. This “hopeful trend toward pessimism” (Duck 1994: 7) has been fundamental to understanding the entirety of human relationships and, specifically, the role of darkness – how it is defined and how it functions in conjunction with the brighter sides of relational life. Recognized as the ones who “labeled and legitimized the dark side of relationships” (Perlman and Carcedo 2011: 2), Spitzberg and Cupach’s published collections have addressed a wide array of dark relational communication issues. In a review of Spitzberg and Cupach’s four edited dark side books, for example, Perlman and Carcedo found that the five topics most frequently addressed were violence, conflict, jealousy, anger, and threats. Scholarship related to bullying, sexual harassment, jealousy, teasing, sexual aggression, and annoyance were topics also covered albeit less frequently (Perlman and Carcedo 2011).

As noted, these collections have impacted the direction of dark side scholarship and certainly reflect contemporary theorizing and empiricism in the field. Olson and colleagues (2012) adapted much of this research to the family environment, developing assertions and characteristics of dark family communication as well as a corresponding model of the processes involved. Moreover, research on the dark side of relating has also crossed into organizational contexts (e.g., for edited volumes, see Fox and Spector 2005; Harden Fritz and Omdahl 2006), as well as the dark side of transformational leadership (Tourish 2013). In addition to the study of clearly dark relations such as intimate partner violence (Johnson 2008) or stalking (Spitzberg and Cupach 2007b, 2014), scholars have also examined the darker side of more positive states and behaviors such as emotional intelligence (Austin et al. 2007, social support (Freisthler, Holmes, and Wolf 2014, technology use (Salanova, Llorens, and Cifre 2013), affectionate communication (Floyd and Pauley 2011) and doctor–patient interactions (Hannawa 2011) to name just a few. Although dark side scholarship abounds, it has been more difficult to provide conceptual clarity to the concept. A review of this journey is next.

Creating a definition of the dark side has proven to be a more challenging task than some may have anticipated. It is a rather slippery construct, encapsulating not only message characteristics, but individual motives and intentions, individual interpretation and meaning-making as well observable behaviors and individual and relational outcomes. In early writings, terms such as elusive, secret, difficult, distressing, hidden, disruptive, hurtful, deceptive, paradoxical, forbidden, deviant (Spitzberg and Cupach 1994), were used to describe the dark side of relating. Additional dark behaviors included those that were considered incompetent and overlooked or would “doom, destroy,or challenge relationships” (Duck 1994: 14, emphasis added). Darkness also referenced distressing relational outcomes (Duck 1994).

In an attempt to further understanding of dark relational forms, Duck (1994) presenteda2×2 taxonomy based upon two dimensions of darkness: intentionality (positive or negative) and dark behavior’s relational embeddedness (inherent or emergent). Those relationships involving good intentions with some regular (inherent) but rather minor negativity involving conflicts or tensions were labeled as having “difficulty”, while those that experienced the development of more serious negative behaviors over time (emergent), such as betrayals or regrets, were identified as “spoiling”. Conversely, “negative relations”, such as bullies or enemies, were described as relationships that were inherently destructive and reflected bad intentions toward the other person. Relationship forms involving and labeled “sabotage” were ones that included bad intentions but negative behaviors that emerged over time, such as the silent treatment or revenge.

1.2Teenage angst

Later, Spitzberg and Cupach (1998b) developed a list of seven deadly sins of darkness, expanding upon the dark side metaphor and adding to the theoretical understanding of the term. While not originally presented in such a way, these sins can be organized around three major themes: cognitions, behaviors, and outcomes (see Table 2 for a complete breakdown). Sins involving dark cognitions capture those processes that occur internally and represent dark thoughts, beliefs, and attitudes. Their darkness is primarily a by-product of cognitive calculations or processing. Specifically, this category includes unpotentiated, unfulfilled needs, assessments of individuals as unwanted or distasteful, or moments that are considered mystifying or unexplainable. Dysfunction, destructive, and distressing actions that impact a person’s ability to function and those that violate social norms, such as betrayal or deviance, are included in the dark behavior category because of their shared performative nature. Finally, dark outcomes are those sins that describe the effects of people’s behavior, including the exploitation and objectification of others.

Tab. 2: Themes of the seven deadly sins of sarkness.

Dark Cognitions –the unfulfilled, unpotentiated, underestimated, and unappreciated – the recognition of unmet needs. –the internal assessment of labeling people unattractive, unwanted, distasteful, and repulsive people –the paradoxical, dialectical, dualistic, mystifying – moments unexplainable. |

Dark Behaviors –dysfunctional, distorted, distressing, and destructive human behavior – actions that “diminishes one’s own [or another’s] ability to function” (p. xiv). –deviance, betrayal, transgression, awkward, rude, disruptive, annoying violations-behaviors that violate social norms. |

Dark Outcomes –the exploitation of the innocent – deeds that harm those with little power. –objectification – people who treat others as inhuman. |

Note: Adapted from Spitzberg and Cupach 1998b.

1.3Emerging adulthood

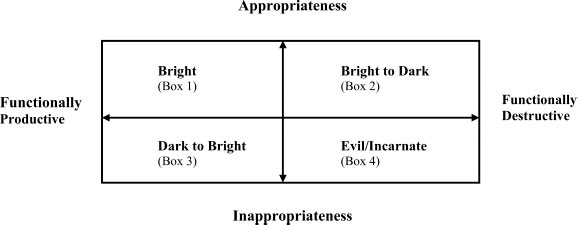

In some of Spitzberg and Cupach’s more recent writings (2007a), they defined the dark side by two dimensions: appropriateness (normatively and morally appropriate/normatively and morally inappropriate) and functionality (productive or destructive). Four domains of dark relationships emerge from this 2 × 2 schemata, representing “the boundaries of the dark side” (see Figure 1).

The quadrants capture the dichotomous bright (Box 1 – normatively and morally appropriate/functionally productive) and dark (Box 2 – normatively and morally inappropriate/functionally destructive) side of relating. Moreover, they also account for categories that embody a murkier perspective on the dark side – one that is filled with more shades of gray. Or, as Spitzberg and Cupach (2007a) assert, this perspective captures those relational situations where dark clouds contain silver linings or where that which was once dark is now bright (Box 3 – normatively and morally inappropriate/functionally productive). Finally, box 4 represents situations where that which was once bright is now dark or, said in a slightly different way, the presence of silver clouds that have dark linings (Box 4 – normatively and morally appropriate/functionally destructive).

Fig. 1: Boundary designations for bright and dark close relationships.

Note: Adapted from Spitzberg and Cupach 2007a.

Most recently, Olson et al. (2012) built upon the theorizing of these earlier scholars, offering numerous assertions regarding dark family communication that further enhances our general understanding of what dark is and how it functions within close relationships. These authors provided several characteristics that describe the dark side of family communication, many of which transcend the family context and are relevant to the current focus on close relationships (for a full review, see Olson et al. 2012). First, Olson and colleagues described the nature of dark communication itself. Dark communication was defined, in part, as “verbal and/or nonverbal messages that are deemed harmful, morally suspect, and or socially unacceptable” (p. 10). This description is very similar to words, such as difficult, hurtful, and inappropriate, used in the early years to describe the nature of darkness. In addition, the researchers argued that dark communication involves various versions of intentionality, which will be discussed in more detail below. In addition, Olson et al. highlight how darkness is not always obscure, but can contain shades of gray (i.e., silver linings) and, perhaps more realistically, exists on a continuum of darkness. There is also an acknowledgement that darkness is not always negative. Instead, messages and behaviors can exist on a darkness continuum, revealing the potential for a both/and perspective. This positive–negative dialectic is important to consider when examining the nature or effect of the darkness experienced.

In addition to describing what constitutes dark communication, Olson et al. (2012) posit assertions related to how dark communication is interpreted and given meaning. They note that since meaning-making occurs at the time of message de-construction, dark thoughts (involving attribution calculations) and dark behaviors can occur at that time. Moreover, dating back to the concept’s conceptual infancy (Duck 1994; Spitzberg 1994b), there appears to be consensus that darkness involves a violation of morality and a degree of social inappropriateness, both of which involve interpretation, meaning-making, and attributions.

What becomes unclear in this line of theorizing is the “who” in this assertion. In other words, who is assessing the inappropriateness or immorality? Who is assigning a meaning of darkness to the message, the behavior? Who is making the attributions? Are they uninvolved onlookers, researchers, mental health professionals, cultural critics? Are they the interactants or members of the cultural group themselves? Or is it a combination of both?

Because meaning-making is vitally important to the definition of darkness, it becomes imperative that the “who” doing the interpreting is integrated into theorizing (Olson et al. 2012 Spitzberg 1993). Those instances where there is agreement between Self and Other make the need to identify the arbiter of assessment less necessary. The matter becomes much more complex and stickier when there are differences between actors’ and observers’ calculations of morality and normativity. A few examples can help clarify the argument. It is possible to imagine a family environment where using a swear word like “damn” would be considered very amoral and inappropriate (Actor assessed). Yet, many other individuals in U.S. society may feel the use of this word is quite normative – and not dark. So, the Actor evaluates the use of the swear word as amoral, whereas the Observer believes it to be quite normal and certainly not amoral. If a researcher wanted to study this phenomenon, would the practice be called dark? Would the study “qualify” for inclusion in a book focusing on the dark side of communication if the behavior is normative and thereby not dark by societal standards?

Another example is provided to muddy the waters more. There are a variety of normalized relational beliefs and practices within some Muslim communities which many outside of these contexts would find amoral and non-normative. For example, sex and parenthood is to happen within marriage (as opposed to premari-tally) and female genital surgery (also called mutilation by outsiders) is practiced within some Muslim and non-Muslim African communities (Dhami and Sheikh 2000). Many individuals within Western cultures (Observers), such as the United States, would find these practices constraining, non-progressive, exploitative, dehumanizing, amoral, and socially inappropriate – in other words, dark. Yet, they are not seen in this light by many members of the cultural group itself (Actors). Who’s correct? Whose definition of dark do we use when attempting to classify dark behavior and understand dark relational processes?

In an attempt to resolve these complexities, Olson and colleagues (2012) asserted that there was a need to account for both possibilities. More specifically, the individual interactants could be the ones assigning meaning, or it could be the uninvolved individuals who observe the [dark] behavior or confront its effect. In a theoretical essay on (in)competence, Spitzberg (1993) similarly argued that schisms could exist between an actor’s and observer’s assessment of competence, labeling them dialectics of inference. Darkness, like competence, involves an evaluation of what is moral and amoral or positive and negative, and those assessments can vary between who is enacting the behavior and who is observing it. Understanding these different possibilities are important to acknowledge because they make a profound difference in how darkness is understood, experienced, measured, and theorized. For instance, a process involving Actor labeled inappropriate behavior would need to account for how that group manages their own negative behavior in a social world (Observer) that considers their actions normative. Conversely, how relational members communicate and navigate their realities when they behave in ways normative to them (Actor labeled appropriate behavior) but non-normative in the larger social context (Observer) is expected to involve many different dynamics than the reverse. To see how such dynamics factor into dark relational processes, continued theoretical development needs to account for all of these possibilities:

1.Actor/Observer appropriate;

2.Actor/Observer inappropriate;

3.Actor inappropriate/Observer appropriate; and

4.Actor appropriate/Observer inappropriate.

Power and ideology are integrally connected to these Actor/Observer dynamics as well as to the overall assessment of appropriateness, morality, and normativity involved in dark communication. It must be acknowledged that the powerful, dominant group is driving the definition of normative (Olson 2009). As such, the dominant group’s beliefs, norms, and behaviors will be the basis for what is moral, appropriate, and normal. The beliefs and behaviors of members of non-dominant groups are amoral, non-normative, and inappropriate just by their membership in the out-group alone. It is quite possible, in fact, that members of non-dominant groups may be more harshly judged for their “inappropriate” behavior (as defined by the dominant group) than dominant group members acting in the same way. This assertion begs empirical testing but it is sufficient to say that any and all assessment of darkness carries with it the ideologies of the powerful cultural group (Spitzberg 1994a). Accordingly, it is essential that scholars interested in the dark side continually monitor the often hidden ideology embedded in the work being done and challenge the assumptions associated with the privileged position.

The issue regarding how a behavior is judged amoral or non-normative is also highly context dependent (Olson et al. 2012). To apprehend what is considered dark or how dark interactions are negotiated, one must do so within the appropriate cultural/contextual frame. As described above, what is dark to some may not be dark to others. Accounting for such cultural nuances can be challenging from a theoretical perspective. Olson et al. (2102) consider this the where part of their perspective – where the meaning-making is made. They advance an ecological approach for analyzing this darkness in context. Their model is very similar to Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) socio-ecological framework, which symbolically captures how behavior is shaped by an individual’s interaction with his or her social world. Although the number and labels can vary, a common version of the framework often accounts for four “levels of influence” (Ali and Naylor 2013; Richard, Gauvin, and Raine 2011) that help explain human behavior. These levels often include the individual (biological and personal factors), relationships (relations with individuals close to individual), community (context, neighborhood, and culture), and society (structures and systems in the culture). These levels are nested within each other and are highly interdependent. To understand dark behavior, analyses need to consider how societal factors, community input, and relational interactions are influencing an individual’s behaviors and also how the individual is impacting each of these interdependent levels.

Finally, one must account for time – or when the darkness occurs. Time can be, according to Olson and colleagues (2012), synchronic (one moment in time) or diachronic (occurring over time). Darkness travels across these dimensions. Imagine, for example, a conflict between two romantic partners that becomes intense and leads to both people using physical aggression. If one were to examine this dark encounter, he or she would assume a synchronic approach to time. Alternatively, if one were to account for how this negative episode impacted the couple’s relational functioning down the road, then a diachronic perspective would be applied. Both are necessary to capture when studying darkness because, as Spitzberg and Cupach (2007a) have argued, dark clouds can contain silver linings or silver linings can turn dark. Time is inherent in each of these statements. A certain amount of time needs to have passed in order for silver linings to emerge from darkness. Moreover, shades of silver take a while to turn dark. Just as relationships change and communication evolves, so too does darkness. It can be stationary and dynamic, short-term and long; it can be intense and subtle, hidden and exposed. Because it can morph into many different shapes and forms, it is essential to account for time when attempting to understand this elusive construct known as relational darkness.

2What is communication competence?

Another “amorphous” (Cupach and Spitzberg 1983; Spitzberg 1994b) concept, known as communication competence (CC), has held the attention of scholars for more than six decades, creating a vast and diverse body of literature (Wilson and Sabee 2003). A detailed review of the varieties of and nuances associated with it are beyond the scope of this chapter. Instead, a brief overview of key components of the construct is presented to lay the necessary groundwork for discussing its relation to dark communication. There are a variety of ways that CC has been defined, but one of the earliest ones that has influenced the CC scholarship the last few decades is Wiemann’s (1993). He defined communication competence as

The ability of an interactant to choose among available behaviors in order that he [sic] may successfully accomplish his [sic] own interpersonal goals during an encounter while maintaining the face and line of his [sic] fellow interactants within the constraints of the situation. (p. 394, emphasis added)

It is important to deconstruct this definition, revealing several basic assumptions about what it means to be a competent communicator. One must first possess (or have the essential cognitive aptitude) the necessary ability to choose from (infer-ring sufficient agency) a repertoire of skills (cognitive, behavioral, and affective) in order to accomplish (implying power and self-efficacy) an interpersonal goal (assuming pre-meditated awareness of goal and lack of influence from other interactants). In addition, the definition captures the relational and cultural sensitivity as well as the contextual embeddedness that are integral to being a skilled communicator.

The “paradigm of niceness” discussed earlier in relation to the lack of darkness in close relationship scholarship has befallen the study of communication competence (Spitzberg and Cupach 2002). This positivity bias is evidenced in the term’s definition just presented. Its tone imbues benevolence and goodwill rather than malevolence and malice. It implies that one has the necessary power and will use it to exercise that goodwill and accomplish respectable goals. It leaves out how certain individuals may not have the requisite abilities, motives, or desires to influence others in a constructive way. In other words, it fails to capture the dark side of being a skilled communicator – how a person with an altered cognitive orientation, ill will, sufficient power, and adequate skills and resources can achieve his/ her own untoward goals, regardless of the harm that may be inflicted, and all the while appearing to maintain the face of his/her interactional partner and operating within the norms of the situation.

Similar to the dark side of communication, communication competence has experienced a constant form of intellectual tinkering. Perspectives toward CC have progressed from a more objective focus on trait/state-based skills, to an awareness of subjectivity and cultural sensitivity, to an increasing examination of the ideologies embedded in definitions of competence. As a way to bring order to the expansive study of communication competence, Spitzberg (1994b) synthesized the literature around three core concepts: abstraction, location, and criteria.

With regard to abstraction, scholars have examined communication competence from a variety of behavioral levels, ranging in the degree of aggregate skills needed to enact the behavior (Spitzberg 1994b). Spitzberg (1994b) labeled these microscopic (e.g., eye contact, gestures, linguistic abilities), mezzoscopic (e.g., self-disclosure, speech acts, jokes), and macroscopic (e.g., adaptability, empathy, compatibility). A significant amount of CC research has focused on identifying what skills are considered competent. Skills, according to Spitzberg (2006), “are the repeatable, goal-oriented behavioral tactics and routines that people employ in the service of their motivation and knowledge” (p. 638). More than 100 microscopic level skills were identified by Spitzberg and Cupach (2002) and slightly modified in later work (Spitzberg and Changnon 2009; Spitzberg and Cupach 2011).

Spitzberg (1994b) identified location as a second core concept describing communication competence. Location in this context considers where the competence resides – in individual abilities, in inferences made by the interpreter, or by members of the social unit. As noted above, abilities and skills have been the dominant paradigm in CC research, inferring in many cases that specific skill sets are transferable to different contexts. In stark contrast is research that notes the subjective nature of competence – that what is considered competent varies across cultures and contexts. Studies in this area identify the mechanisms for how and why individuals judge some behavior as competent.

Criteria, or standards for judging competence, is the third key notion associated with communication competence (Spitzberg 1994b). Spitzberg and Cupach (2002, 2011) describe six common criteria for quality interactions in relationships: fidelity, satisfaction, efficiency, effectiveness, appropriateness, and ethics (also see Chapters 3 and 22 in this handbook for further review). Yet, as noted by Spitzberg and Cupach (2011), any single criterion has its flaws and is limited in its ability to assess a quality interaction. Instead, the use of two of these criteria, appropriateness and effectiveness, does provide rather solid footing for determining communication quality. Spitzberg and Cupach (2011) assert that “Communication that accomplishes preferred objectives in a manner judged legitimate by others is likely to be satisfying and ethical as well” (p. 498). These two well-established criteria are reviewed further.

Effectiveness, described as being the oldest and most well-established competence criterion (Spitzberg and Cupach 2002), is defined as the accomplishment of preferred or desired outcomes (Canary and Spitzberg 1987; Spitzberg 1994; Spitz-berg, Canary, and Cupach 1994; Spitzberg and Cupach 2002) or the “extent to which a communicator achieves objective(s)” (Spitzberg 2000: 105). Assuming most people in relationships have positive goals, many preferred outcomes would be correspondingly positive. However, and unfortunately, this is not always the case; many individuals have destructive goals and/or use unsavory means to achieve their goals, such as the online seduction of children by adults (for discussion of dark side of computer mediated communication, see DeAndrea, Tong, and Walther 2011) or the loss of something valuable (i.e., thousands of dollars) as a result of an elaborate and effective confidence (con) game (for an analysis of confidence games carried out by con men, such as Bernard Madoff, see Lewis 2013).

From an effectiveness and functionalist point of view, the predator and the con achieved their goals. Yet, most would say that the preferred goal and achieved outcome in these instances are unethical and inappropriate. With that in mind, it is hard from a societal perspective to label the “effective” behavior as competent – yet it is functionally (see discussion of dialectic of motive, Spitzberg 1993). Another concern related to effectiveness is that the concept can also be difficult to measure because of the inability to objectively assess another’s “preferred” outcome (for further discussion, see Spitzberg and Cupach 2002). As a result of the potential for effectiveness to be disconnected from a larger societal view of normativity and the challenges associated with measuring it objectively and accurately, scholars argue that this criterion alone is not a sufficient determinant of competent communication.

The other criterion that is paired with effectiveness and does account for normativity is known as appropriateness. Appropriateness is defined as behavior that is contextually normative, legitimate, and follows valued and prescribed rules (Spitzberg 1994b; Spitzberg and Cupach 2002). Because context and culture are driving forces for determining what is legitimate, moral, ethical, or normative, appropriateness is highly context-dependent. In fact, according to Spitzberg and Cupach (2002), it is “assumed that contexts ‘possess’ such standards of appropriateness” (p. 581).

While a valuable criterion for determining communication competence, appropriateness is also not without its problems. Most notably, this criterion has been criticized for being too focused on the judgment of others (in contrast to effectiveness which is critiqued for being too connected to the individual). The troublesome positive correlation between rape myth acceptance and sexual aggression among young men (O’Donohue, Yeater, and Fanetti 2003) or the socially accepted practice of dowry deaths in India (Banerjee 2014) are two dark examples that highlight the problematic nature of relying too excessively on the judgments of “the other”. Related to the earlier darkness discussion, “the other” in assessing the communication competence criterion of appropriateness becomes problematic when there is no identified other or there are multiple competing others (Spitzberg and Cupach 2002).

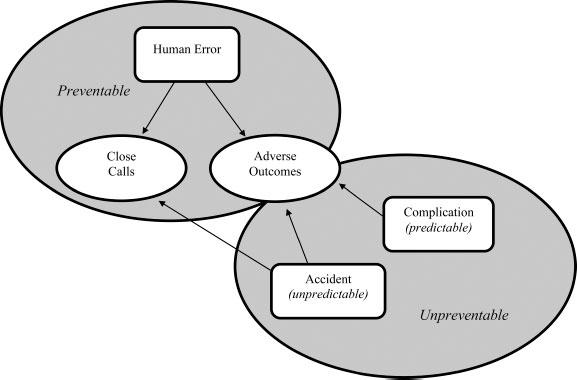

Each criterion by itself is clearly insufficient as a definition of communicative competence. To rectify this shortcoming, researchers have argued that communication competence is a combination of both appropriateness and effectiveness. Spitz-berg, Canary, and Cupach (1994) provided a heuristic device to describe the categories of behaviors resulting from the integration of the two criteria: appropriateness/ inappropriateness (A/iA) and effectiveness/ineffectiveness (E/iE) (see Figure 2). Two categories described appropriate (A) behaviors, which differed in their effectiveness (optimizing [A/E] and sufficing [A/Ie]). Clearly, the optimizing category is considered the most ideal by communication competence standards. In contrast, minimizing (iA/iE) would be classified as the least ideal, and maximizing (iA/E) perhaps the most potentially dark. Socially inappropriate types of communication, such as verbal aggression or sexual innuendos shared with children, can be very effective when a person achieves his/her goals of control, compliance, or illegal sexual interactions (e.g., Olson 2002; Olson et al. 2007).

In an attempt to bring more theoretical structure to the area of study, Spitzberg and Cupach (2011) presented a taxonomy of interpersonal skills and functions. Working from left to right, the taxonomy presents a framework of concepts that are organized from specific to general or micro to macro levels of abstraction. The structure also accounts for differences in forms of competent communication, which fulfill different functions of competence. The relationships between these levels can be presented as follows in text form:

Fig. 2: Taxonomy of communication competence behaviors.

Note: Information adapted from: a Spitzberg, Canary, and Cupach 1994; b Olson 2002.

Form at Micro and Mezzo Levels →→ Function at Micro and Mezzo Levels

Forms of micro level behaviors include, for example, head nods, vocal confidence, expression of opinion, eye contact, and speaking rate. The variety of micro behaviors are grouped into higher order categories (mezzo level) including attentiveness, composure, coordination, and expressiveness. These higher order forms of competent behavior serve various micro level functions (e.g., empathy, ego-supporting, persuasive, and disclosure). The lower order functions comprise six mezzo levels: intimacy, predictability, closedness, autonomy, openness, and novelty. An example will demonstrate more concretely the relationships presented in the taxonomy. According to Spitzberg and Cupach (2011), behaviors such as head nods and asking questions are micro-level actions that constitute the mid-range behavior called attentiveness. In turn, attentiveness is hypothesized to serve several micro-level functions such as empathy, concern, comfort, support, and interest. These lower-order functions like empathy are proposed to then constitute higher order functions, such as intimacy. Said in a more formulaic way,

head nods (micro form) → attentiveness (mezzo form) →→ empathy (micro function) → intimacy (mezzo function)

This current taxonomy adds an important component to the skills literature that is especially relevant to the current discussion. Breaking away from the positive bias, this theoretical presentation now includes skills that could be considered grayer than others identified previously. Examples include micro level skills such as topic initiation and maintenance serving to fulfill the function of communication closedness. Recent studies have demonstrated this more positive side of closedness. For example, in their study with military families, Joseph and Afifi (2010) found that wives were less likely to disclose stressors (a form of topic initiation and maintenance) to their deployed husbands when they perceived that their husbands’ safety was at risk. This lack of disclosure was a form of protective buffer, allowing the wives to protect their partners from feelings of stress. Baxter et al. (2002) found a similar finding in their research with elderly wives whose husbands were institutionalized with dementia. The wives reported consciously choosing not to disclose stressors they were experiencing in their own life, such as financial strain, in order to protect their husbands’ from feeling guilty for not being able to care for them.

In sum, the communication competence literature has evolved over time, moving from a myopic focus on the more positive side of competence to one that is beginning to acknowledge a grayer shade of interpersonal skills. The integration of darkness and communication competence is explicated more fully below.

3How can communication competence be dark?

The concern now becomes how and when the skills associated with being a competent communicator take on shades of darkness. In other words, what is the relationship between dark competence and communication competence? Researchers have occasionally associated incompetence with darkness (e.g., Spitzberg 1994b). Communicating in ways that are harmful, deceptive, or disruptive (aka dark) is typically construed as incompetent behavior. Dark actions could then be viewed as a form of incompetence (referencing Spitzberg and Cupach’s 2002 taxonomy). Depending upon how it is conceptualized, darkness could also be an outcome associated with incompetent communication. For example, research has shown that non-constructive conflict management (an incompetent communication skill) is associated with relational aggression (a dark outcome) (e.g., Olson and Braithwaite 2004). In contrast, incompetence can be defined by dark behaviors but also by bright behaviors that are just ineffective (i.e., unsuccessful attempts at persuasion). From these comparisons, one can see that, to date, darkness is almost always considered incompetent, and, while incompetence is often associated with darkness, it can assume non-dark forms and function in non-dark ways. Incompetence, thus, is not synonymous with darkness. Equally faulty is the belief that competence and darkness are on opposite ends of an interpersonal skills continuum. They certainly possess different conceptual space, but they also may assume similar forms and serve similar functions. The remainder of this chapter will examine this darker side of competence by considering several dimensions that help define the construct dark competence. Importantly, dark competence is grounded in the characteristics of dark communication discussed earlier as well as the perspective toward communication competence articulated herein. The dimensions which follow are deemed most salient to help differentiate dark competence from its kin, dark communication and communication competence, providing the concept with its own theoretical space. Following the review of dimensions, questions for future consideration will bring the chapter to a close.

3.1Dimensions of dark competence

3.1.1.Intent/motive

Aside from the noted exception of the development of a cognitive competence measure (Duran and Spitzberg 1995), most communication competence research focuses on observational, performative behavior. In contrast, since the early days (e.g., Duck 1994), research on dark processes, such as intimate partner violence, sexual assault, and dark family communication, typically integrate intent into their conceptualizations. For example, Cahn (2009) defines family violence as:

Imposing one’s will (i.e., wants, needs, or desires) on another family member through the use of verbal or nonverbal acts, or both, done in a way that violates socially acceptable standards that are either (1) carried out with the intention or perceived intention of inflicting physical or psychological pain, injury, and/or suffering, or (2) in the case of incest, of sexually exploiting a relative of one’s own or of one’s significant other under 18 years of age. (p. 16, emphasis added)

Real life examples and research studies demonstrate the communicative skills of individuals who are very dark behind their competence disguise. They become very skilled at deceiving others into thinking they are truthful, honest, and have good will. These dark intents combined with strong communicative abilities can lead to horrific outcomes. Investment banker Bernie Madoff demonstrated a cunning ability to convince people to invest their life fortunes with his investment firm, which ended up being a Ponzi scheme that led to many people losing thousands of dollars (Lewis 2013). Eventual abusers begin their grooming process by showering their partner with love and attention, which is really about setting the stage for future control, isolation, and demoralization of the unknowing partner (Olson 2004). The case of Jerry Sandusky reminds us that child sexual abusers roam the halls of institutions of higher learning, big time college sports, and influential non-profits designed to help children, not harm them as Sandusky so craftily did. He was a skilled communicator who ensnared his child victims into a cycle of entrapment (Olson et al. 2007), luring them into ongoing sexual relationships that have impacted them to this day (Adamson et al. 2013).

This dark side of competence is perhaps the scariest of all. It is elusive and difficult to discern, but when it is allowed to be carried out, it harms individuals deeply, shatters their trust in others, and creates a cynical outlook of the world that limits people’s ability to enjoy the beauty of life. Its ability to damage lives is all the more reason to do what is possible to assure our understanding of what is considered competent and dark is examined more fully. Doing so involves extending research on dark competence beyond that which can be observed to include that which cannot – the motives and intentions of interactants.

When seeking to understand dark competence, it is vitally important to account for the individuals’ internal motivations, intents, and perceptions because of how integral these cognitions are to human behavior. Darkness is inherently connected to the human psyche. Yet, it is manifested in social interactions (Duck 1994). As such, connections must be made between the internal states, human interactions, and outcomes in order to flesh out further the idea of dark competence.

3.1.2Positivity-negativity dialectic

This chapter has shown how perspectives on dark communication often view it primarily as involving negative intents, behaviors, or outcomes. Conversely, communication competence has been critiqued for privileging only the bright side of relational functioning and only those skills that carry a “normatively positive valence” (Spitzberg and Cupach 2002: 589). These either/or perspectives have limited application to the messiness of human relationships. As has been discussed, darkness needs to be considered alongside bright interactions. A less common argument made, but one that is equally as important, is that a bright approach to competence needs to acknowledge that darkness may occasionally be a helpful ability. There may be times, for example, when using aggression to resolve a conflict may be a useful skill (for further discussion see Spitzberg and Cupach 2002; Olson 2002), keeping secrets from a partner or other family member may serve a self- or other-protective role (Afifi, Olson, and Armstrong 2005; Baxter et al. 2002; Joseph and Afifi 2010), or inducing jealousy can produce positive relational outcomes (Fleischmann et al. 2005). Researchers have also noted that there are times when communication errors, which could be viewed as dark, can also lead to positive self-reflection, learning, and communicative change such as in the awkward incidents of social predicaments (Cupach 1994) or regretted communication (Meyer 2013).

Conversely, bright, competent behaviors can assume shades of darkness. Spitz-berg (1994b) described how, for instance, empathy, perspective taking, and cognitive complexity can have negative, less healthy effects. In addition, researchers have found maladaptive aspects of happiness (Gruber, Mauss, and Tamir 2011); self-forgiveness can inhibit behavioral change such as smoking cessation (Wohl and Thompson 2011); and too much self-regard may prompt violence and aggression in situations involving threatened egotism (Baumeister, Smart, and Boden 1996). Self-monitoring is another skill that can become dark. High self-monitors are individuals who are sensitive to the appropriateness of social situations and able to regulate their behavior appropriately (Snyder 1987). As such, these individuals are considered especially competent in their interactions and social settings. However, Wright, Holloway, and Roloff (2007) found that a high self-monitor’s tendency, depending upon the situation, to adjust his/her presentation of self and to mask true feelings can also be associated with less intimate communication and lower relationship quality. Similarly, social comparison is thought to be a normative, integral part of the human experience. Unfortunately, however, there can be a dark side to comparing one’s self to others. For example, White and colleagues’ (2006) study found a positive relationship between frequent social comparisons and negative emotions, such as envy, guilt, and regret, and defensive and deceptive behaviors, and others who have noted the profoundly troubling role that “pro-anorexia” websites and blogs play in supporting and suggesting the normality of an Ana way of life (Castro and Osorio 2012; DeAndrea, Tong, and Walther 2011). Not only are these websites places where individuals turn for support but also for the ability to compare one’s self to and to learn from others with similar mental disorders. As the pro-anexoria study based in Portugal reveals, the “Ana way of life” knows no geographic boundaries (Castro and Osorio 2012) and demonstrates a darker side of social support.

In order to more fully capture the complexities of relational life, the both/and philosophy, which is embedded in the positive–negative dialectic needs to be integrated into the study and theorizing of dark competence. Being a skillful communicator does not mean the person always acts with good intent, grace, and humility. Instead there may be times when skill casts a gray shadow on human interaction, revealing that intent, behaviors, and outcomes may assume unpleasant forms.

3.1.3.Time

Time is often necessary for darkness to be viewed as competent (synchronic) or for it to function (diachronic) as competence. With few exceptions (e.g., Spitzberg 1987), however, much of the theorizing on communication competence (CC) ignores this factor. Spitzberg and Cupach (2002) added time as a criterion of communication competence, but few empirical examinations of the relationship between time and CC exist. Instead, a snapshot often is taken, capturing and assessing CC at one moment in time. This practice becomes problematic because understanding how behaviors function involves the passage of time. For example, if the picture was taken when a wife physically assaulted her husband, her actions would be deemed incompetent and, in many states where mandatory arrests for domestic battery exist, could put her in jail. Yet, time is essential to understanding how the both bright and dark perspective works in this situation and in relation to dark competence and communication competence, more broadly. In order to see the silver linings in the dark clouds, time needs to have passed. The darkness of the aggression enacted by the wife could have been her act of retaliation for the abuse she had been suffering and very well could contain silver linings when it leads her to say, “Enough is enough. I’ve got to get out of this relationship.” This example shows how darkness can function positively – or when bad can be good.

3.1.4.Contextual embeddedness

Finally, understanding how communication is interpreted and assigned meaning can play a major role in being better equipped to answer the questions and complexities of dark competence that were raised in this chapter. Knowledge of the culture and context within which the thoughts and behaviors occur is fundamental as well. As noted, context is inherent to dark communication and communication competence as separate constructs but also to their conjoined twin, dark competence. One example of this is a study by Olson (2002) who found that couples experiencing aggression tended to see the appropriateness and effectiveness of their aggression functioning in ways that deviated from standard custom and the taxonomy of competent behaviors identified by Spitzberg, Canary, and Cupach (1994) (see italicized words on Figure 2). Several individuals viewed their use of aggression as inappropriate but effective, yet like the label maximizing suggests, evaluated it as negative. There were other instances, however, when the participants viewed their use of aggression as unyielding (not minimizing), vindicating (not optimizing), and agitating (not sufficing). The findings from this study represent one example of the context-dependent nature of dark competence.

4What’s next?

As this chapter comes to a close, it is instructive to turn the ideas addressed herein into actual areas of future inquiry. The socio-ecological framework discussed earlier will serve as an organizing heuristic. Ideas for future research at each level are offered.

4.1The individual

To begin, we must, in a way, back-up, meaning we need to step back from current practices to include the intentions and motivations of the interactants. As noted, past communication competence research has not often examined individual intent while scholarship on many dark processes (e.g., intimate partner violence, sexual assault) typically does address the motives of the perpetrator. Future research needs to examine what motives drive the communicative enactment of dark competence. More knowledge about individuals’ characteristics, personality, beliefs, and attitudes is also needed to better understand through a dark competence lens how and why messages are constructed and processed as well as why certain behaviors are performed.

4.2Relational

The next level in the socio-ecological model focuses attention on how the intentions, actions, and behaviors of the individual are influenced by his/her relationships and vice versa. For instance, what types of relational climates are particularly susceptible to the development of dark competence? How do individuals who can communicate competently in dark ways influence his/her relationships? Are those relationships changed by these individuals? Questions that focus on the interconnectedness of individuals and relationships are important to advancing the study of dark competence.

4.3Community

The impact of the context, neighborhood, and culture are representative of the community level of the socio-ecological framework. As discussed previously, contextual embeddedness is essential to understanding what constitutes darkness. Related to the present topic, one might consider how a particular culture is influencing an individual’s dark competence, which is also interconnected to her/his relationships. As an example, how might the prevalence of neighborhood gangs influence the development of dark competence in the individual? How do individuals’ relationships reinforce those beliefs further fostering the development and enactment of dark competence?

4.4Social

All individual, relational, and community levels are also influenced by the larger social system in which they exist. Specifically, customs, laws, and policies impact the development and enactment of dark competence. These structures can reinforce the darkness or fight against it. How, for example, might the social norm which accepts violence as a way of managing conflict further perpetuate a person’s ability to convince his partner that the slap across the face was effective in bringing their argument to an end? What social structures are particularly powerful in creating and enabling individuals’ dark competence? How do relationships and communities reinforce such behavior? How did institutional and social structures and relationships, for instance, create such a high pedestal of power and prestige for a Division I college football coach like Jerry Sandusky that the reality of his abuse of children was denied and allowed to continue for years? Questions such as these draw attention to the need to widen the empirical lens when studying dark communication and competence. Darkness at its core is individual, relational, communal, and social. Dark competence could become both the vehicle for navigating through this terrain as well as the getaway car when it comes time to change directions.

5Conclusion

This chapter has taken a journey through the dark side of a world that many would prefer to believe does not exist – a world where many days are cloudy and gray, but yet, many nights contain bright moons. Just as night is to day, so is the bright to the dark side of relating and darkness to communication competence. Dark competence captures the potential for ill intents, hurtful messages, biased message processing, injurious behaviors and/or unhealthy individual and relational outcomes. Dark competence is meaningless without relevant context to assign it meaning, and it is unnaturally static without the dynamism of time. Yet, among this darkness is also the potential for light. Ill intents and biased processing can become constructive cognitions and hurtful messages and injurious behaviors can become beneficial actions. Malevolent encounters can become benevolent movements. Such is the world of being human and the true color of communication.

References

Adamson, Nicole A., Connie S. Albert, Emily C. Campbell, and Loreen N. Olson. 2013. Face-to-face sexual abuse and Luring Communication Theory: A case study of Jerry Sandusky. Paper presented to the Carolinas Communication Association conference, October, Charlotte, NC.

Afifi, Tamara D., Loreen N. Olson and Christine Armstrong. 2005. The chilling effect and family secrets: Examining the role of self protection, other protection, and communication efficacy. Human Communication Research 31. 564–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1468–2958.2005.tb00883.x

Ali, Parveen and Paul B. Naylor. 2013. Intimate partner violence: A narrative review of the feminist, social and ecological explanations for its causation. Aggression and Violent Behavior 18. 611–619. doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2013.07.009

Arroyo, Annalise and Chris Segrin. 2011. The relationship between self- and other-perceptions of communication competence and friendship quality. Communication Studies 62. 547–562. doi: 10.1080/10510974.2011.580037

Austin, Elizabeth J., Daniel Farrelly, Carolyn Black and Helen Moore. 2007. Emotional intelligence, Machiavellianism and emotional manipulation: Does EI have a dark side? Personality and Individual Differences 43. 179–189. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2006.11.019

Banerjee, Pirya R. 2014. Dowry in 21st-century India: The sociocultural face of exploitation. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse 15. 34–40. doi: 10.1177/1524838013496334

Baumeister, Roy F., Laura Smart and Joseph M. Boden. 1996. Relation of threatened egotism to violence and aggression: The dark side of high self-esteem. Psychological Review 103. 5–33. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.103.1.5

Baxter, Leslie A., Dawn O. Braithwaite, Tamara D. Golish and Loreen N. Olson. 2002. Contradictions of interaction for wives of husbands with adult dementia. Journal of Applied Communication Research 30. 1–26. doi: 10.1080/00909880216576

Bronfenbrenner, Urie. 1979. The Ecology of Human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cahn, Dudley D. 2009. An evolving communication perspective on family violence. In: D. D. Cahn (ed.), Family Violence: Communication Processes 1–24. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Canary, Daniel J. and Brian Spitzberg. 1987. Appropriateness and effectiveness perceptions of conflict strategies. Human Communication Research 14. 98–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.1987.tb00123.x

Castro, Teresa S. and Antonio Osorio. 2012. Online violence: Not beautiful enough / not thin enough. Anorectic testimonials in the web. PsychNology Journal 10. 169–186.

Cupach, William R. 1994. Social predicaments. In: Willian R. Cupach and Brian H. Spitzberg (eds.), The Dark Side of Interpersonal Communication, 159–180. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Cupach, William R. and Brian H. Spitzberg. 1983. Trait versus state: A comparison of dispositional and situational measures of interpersonal communication competence. The Western Journal of Speech Communication 47(4). 364–379.

Cupach, William R. and Brian H. Spitzberg. 1994. Preface. In: William R. Cupach and Brian H. Spitzberg (eds.), The Dark Side of Interpersonal Communication, vii–ix. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

DeAndrea, David C., Stephanie Tom Tong and Joseph B. Walther. 2011. Dark sides of computer-mediated communication. In: William R. Cupach and Brian H. Spitzberg (eds.), The Dark Side of Close Relationships II, 95–118. New York: Routledge.

Dhami, Sangeeta and Aziz Sheikh. 2000. The Muslim family: Predicament and promise. Western Journal of Medicine 173. 352–356.

Duck, Steve. 1994. Stratagems, spoils, and a serpent’s tooth: On the delights and dilemmas of personal relationships. In: William R. Cupach and Brian H. Spitzberg (eds.), The Dark Side of Interpersonal Communication, 3–21. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Duran, Robert L. and Brian H. Spitzberg. 1995. Toward the development and validation of a measure of cognitive communication competence. Communication Quarterly 43. 259–275. doi: 10.1080/01463379509369976

Fleischmann, Amy A., Brian H. Spitzberg, Peter A. Andersen and Scott C. Roesch. 2005. Tickling the monster: Jealousy induction in relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 22. 49–73. doi: 10.1177/0265407505049321

Flora, Jeanne and Chris Segrin. 1999. Social skills are associated with satisfaction in close relationships. Psychological Reports 84. 803–804. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1999.84.3.803

Floyd, Kory and Perry Pauley. 2011. Affectionate communication is good, except when it isn’t: On the dark side of expressing affection. In: William R. Cupach and Brian H. Spitzberg (eds.), The Dark Side of Close Relationships II, 145–174. New York: Routledge.

Fox, Suzy, and Paul E. Spector (eds.). 2005. Counterproductive Work Behavior: Investigations of Actors and Targets. Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Freisthler, Bridget, Megan R. Holmes and Jennifer Price Wolf. 2014. The dark side of social support: Understanding the role of social support, drinking behaviors and alcohol outlets for child physical abuse. Child Abuse and Neglect 38. 1106–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.03.011

Gruber, June, Iris B. Mauss and Maya Tamir. 2011. A dark side of happiness? How, when, and why happiness is not always good. Perspectives on Psychological Science 6. 222–233. doi:10.1177/1745691611406927

Hannawa, Annegret F. 2011. Shedding light on the dark side of doctor–patient interactions: Verbal and nonverbal physicians communicate during error disclosures. Patient Education and Counseling 84. 344–351. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.04.030

Harden Fritz, Janie M. and Becky Omdahl (eds.). 2006. Problematic Relationships in the Workplace. New York: Peter Lang.

Infante, Dominic A., Teresa A. Chandler and Jill E. Rudd. 1989. Test of an argumentative skill Deficiency model of interspousal violence. Communication Monographs 56. 163–177. doi: 10.1080/03637758909390257

Johnson, Michael P. 2008. A Typology of Domestic Violence: Intimate Terrorism, Violent Resistance, and Situational Couple Violence. Lebanon, NH: Northeastern University Press.

Joseph, Andrea L. and Tamara D. Afifi. 2010. Military wives’ stressful disclosures to their deployed husbands: The role of protective buffering. Journal of Applied Communication Research 38. 412–434. doi: 10.1080/00909882.2010.513997

Lewis, Lionel S. 2013. The confidence game: Of others and of Bernard Madoff. Social Science and Public Policy 50. 283–292. doi 10.1007/s12115-013-9656-y

Mackenzie, Lauren and Megan Wallace. 2011. The communication of respect as a significant dimension of cross-cultural communication competence. Cross-cultural Communication 7. 10–18. doi:10.3968/j.ccc.1923670020110703.175

Meyer, Janet, R. 2013. Contemplating regretted messages: Learning-oriented, repair-oriented, and emotion-focused reflection. Western Journal of Communication 77. 210–230. doi: 10.1080/ 10570314.2012.733793

O’Donohue, William, Elizabeth Yeater and Matthew Fanetti. 2003. Rape prevention with college males: The roles of rape myth acceptance, victim empathy, and outcome expectancies. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 18. 513–531. doi: 10.1177/0886260503251070

Olson, Loreen N. 2002. “As ugly and painful as it was, it was effective”: Individuals’ unique assessment of communication competence during aggressive conflict episodes. Communication Studies 2. 171–188. doi: 10.1080/10510970209388583

Olson, Loreen N. 2004. The role of voice in the (re)construction of a battered woman’s identity: An autoethnography of one woman’s experiences of abuse. Women’s Studies in Communication 27. 1–23. doi: 10.1080/07491409.2004.10162464

Olson, Loreen N. 2009. Deviance and human relationships. In: Harry T. Reis and Susan Sprecher (eds.), Encyclopedia of Human Relationships, 415–417. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Olson, Loreen N., Elizabeth Baoicchi-Wagner, Jessica Wilson Kratzer and Sarah Symonds. 2012. The Dark Side of Family Communication. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Olson, Loreen N. and Dawn O. Braithwaite. 2004. “If you hit me again, I’ll hit you back:” Conflict management strategies of individuals experiencing aggression during conflicts. Communication Studies 55. 301–315. doi: 10.1080/10510970409388619

Olson, Loreen N., Joy L. Daggs, Barbara L. Ellevold and Teddy K. Rogers. 2007. The communication of deviance: Toward a theory of child sexual predators’ luring communication. Communication Theory 17. 231–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2007.00294.x

Perlman, Daniel, and Rodrige J. Carcedo. 2011. Overview of the dark side of relationships research. In: William R. Cupach and Brian H. Spitzberg (eds.), The Dark Side of Close Relationships II, 1–37. New York: Routledge.

Richard, Lucie, Lisa Gauvin and Kim Raine. 2011. Ecological models revisited: Their uses and evolution in health promotion over two decades, Annual Review of Public Health 32. 307– 326. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101141

Salanova, Marisa, Susana Llorens and Eva Cifre. 2013. The dark side of technologies: Technostress among users of information and communication technologies. International Journal of Psychology 48. 422–436. doi: 10.1080/00207594.2012.680460.

Segrin, Chris., Alesia Hanzal, Carolyn Donnerstein, Melissa Taylor and Tricia Domschke. 2007. Social skills, psychological well-being, and the mediating role of perceived stress. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping 20. 321–329. doi: 10.1080/10615800701282252

Snyder, Mark. 1987. Public Appearances/Private Realities: The Psychology of Self-Monitoring. New York: WH Freeman and Company.

Spitzberg, Brian H. 1987. Issues in the study of communicative competence. In: Brenda Dervin and Melvin J. Voight (eds.), Progress in Communication Sciences, vol. 8. 1–46. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. doi: 10.1016/0147-1767(89)90012-

Spitzberg, Brian H. 1993. The dialectics of (in)competence. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 10. 137–158. doi: 10.1177/0265407593101009

Spitzberg, Brian H. 1994a. Ideological issues in competence assessment. In: S. Morreale, M. Brooks, R. Berko and C. Cooke (eds.), Assessing College Student Competency in Speech Communication (1994 SCA Summer Conference Proceedings), 129–148. Annandale, VA: Speech Communication Association.

Spitzberg, Brian H. 1994b. The dark side of (in)competence. In: William R. Cupach and Brian H. Spitzberg (eds.), The Dark Side of Interpersonal Communication, 25–49. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Spitzberg, Brian H. 1997. Violence in intimate relationships. In: William R. Cupach and Dan J. Canary (eds.), Competence in Interpersonal Conflict, 174–201. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Spitzberg, Brian H. 2000. What is good communication? Journal of the Association for Communication Administration 29. 103–119.

Spitzberg, Brian H. 2006. Preliminary development of a model and measure of computer-mediated communication (CMC) competence. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 11. 629–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2006.00030.x

Spitzberg, Brian H., Dan J. Canary and William R. Cupach. 1994. A competence-based approach to the study of interpersonal conflict. In: Dudley D. Cahn (ed.), Conflict in Personal Relationships, 183–202. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Spitzberg, Brian H. and Gabrielle Changnon. 2009. Conceptualizing intercultural communication competence. In: Darla K. Deardorff (ed.), The SAGE Handbook of Intercultural Competence, 2–52. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Spitzberg, Brian H. and William R. Cupach 1994. Dark side of dénouement. In: William R. Cupach and Brian H. Spitzberg (eds.), The Dark Side of Interpersonal Communication, 315–320. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Spitzberg, Brian H. and William R. Cupach. 1998a. Preface. In: Brian H. Spitzberg and William R. Cupach (eds.), The Dark Side of Close Relationships, vii–x. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Spitzberg, Brian H. and William R. Cupach. 1998b. Introduction: Dusk, detritus, and delusion: A prolegomenon to the dark side of close relationships. In: Brian H. Spitzberg and William R. Cupach (eds.), The Dark Side of Close Relationships, xi–xxii. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Spitzberg, Brian H. and William R. Cupach. 2002. Interpersonal skills. In: Mark L. Knapp and John A. Daly (eds.), Handbook of Interpersonal Communication, 564–611. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Spitzberg, Brian H. and William R. Cupach. 2007a. Disentangling the dark side of interpersonal communication. In: Brian H. Spitzberg and William R. Cupach (eds.), The Dark Side of Interpersonal Communication, 3–28. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Spitzberg, Brian H. and William R. Cupach. 2007b. The state of the art of stalking: Taking stock of the emerging literature, Aggression and Violent Behavior 12. 64–86. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2006.05.001

Spitzberg, Brian H. and William R. Cupach. 2011. Interpersonal skills. In: Mark L. Knapp and John A. Daly (eds.), Handbook of Interpersonal Communication (4th ed.), 481–524. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Spitzberg, Brian H. and William R. Cupach. 2014. The Dark Side of Relationship Pursuit: From Attraction to Obsession and Stalking. New York: Routledge.

Stewart, Alan E. and Elizabeth A. Stewart. 2006. The preference to excel and its relationship to selected personality variables. Journal of Individual Psychology 62. 270–284.

Tourish, Dennis. 2013. The Dark Side of Transformational Leadership: A Critical Perspective. New York: Routledge.

Vangelisti, Anita L., Mark L. Knapp and John A. Daly. 1990. Conversational narcissism. Communication Monographs 57. 251–274. doi: 10.1080/03637759009376202

White, Judith B., Ellen J. Langer, Leeat Yariv and John C. Welch IV. 2006. Frequent social comparisons and destructive emotions and behaviors: The dark side of social comparisons. Journal of Adult Development 13. 36–44. doi: 10.1007/s10804-006-9005-0.

Wiemann, John M. 1993. Explication and test of a model of communicative competence. In: Sandra Petronio, Jess K. Alberts, Michael L. Hecht and Jerry Buley (eds.), Contemporary Perspectives on Interpersonal Communication, 390–409. Dubuque, IA: WCB Brown and Benchmark.

Wilson, Steven R. and Christina Sabee. 2003. Explicating communicative competence as a theoretical term. In: John O. Greene and Brant R. Burleson (eds.), Handbook of Communication and Social Interaction Skills, 3–50. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Wohl, Michael J. A. and Andrea Thompson. 2011. A dark side to self-forgiveness: Forgiving the self and its association with chronic unhealthy behavior. British Journal of Social Psychology 50. 354–364 doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.2010.02010.x

Wright, Courtney N., Adrienne Holloway and Michael E. Roloff. 2007. The dark side of self-monitoring: How high self-monitors view their romantic relationships. Communication Reports 20. 101–114. doi: 10.1080/08934210701643727

Wright, Kevin B., Jenny Rosenberg, Nicole Egbert, Nicole Ploeger, Daniel R. Bernard and Shawn King. 2013. Communication competence, social support, and depression among college students: A model of Facebook and face-to-face support network influence, Journal of Health Communication 18. 41–57. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.688250

Yum, June O. 2012. Communication competence: A Korean perspective. China Media Research 8. 11–17.