28Verbal and physical aggression

Abstract: This chapter provides a review and critique of the literature connecting aggression to communicative competence. First, links in the literature between of aggression and conflict are reviewed, acknowledging the constructive potential of conflict. There is a presumption among aggression scholars that aggression is destructive; however, constructive forms of aggression have long been conceptualized. The literature on communication predispositions to aggression defines aggression as the application of force, distinguishes symbolic from physical aggression, and explicates its constructive and destructive forms (argumentativeness and verbal aggressiveness). The relationship of aggression to communication competence is discussed, linking communication predispositions of aggression to communicator skill. Related theoretical models are reviewed, including the theory of independent-mindedness, argumentative skill deficiency, and a model of aggression competence. Related research on aggression and competence is then reviewed, including positive and negative presumptions about violence. The difficulty of applying a competence framework to intentionally harmful behavior is addressed. Special attention is given to verbal aggression, anger, children’s aggression, and intimate partners. The chapter concludes that some aggressive communication may indeed be considered competent, and that the links between harmful communicative aggression and competence are unclear. The dichotomous consideration of nonaggression as good and aggression as bad does not reflect extant research. While individual skills are important, the key to understanding argument, verbal aggression, physical aggression, and the relative communication competencies associated with them lie at the relational, family, or other group-level systems level.

Keywords: aggression, verbal aggressiveness, argumentativeness, intimate partner violence, appropriateness, effectiveness, independent mindedness, argumentative skill deficiency, aggression competence, physical aggression

1Introduction

Behavioral scholars have a long history of theorizing and investigating aggression, in a variety of forms and contexts. For purposes of scope and focus, this chapter will concentrate on interpersonal aggression. In general, treatments of interpersonal aggression presume the presence of conflict, though conflict itself is rarely theorized in studies of aggression. In conflict studies across disciplines, there is a general emphasis on the constructive potential of conflict to enhance critical thinking, build consensus on issues, and strengthen relationships, among other positive effects. Conflict itself, it is often said, is inevitable, and so it is not conflict by nature that is unpleasant or destructive, but rather our conflict management behavior that determines our assessment of the process and/or outcome as good or bad. However, aggression scholars hold an implicit assumption that aggression is negative and destructive, hence its appearance as a “dark side” issue in this volume. Certainly, the links between aggression and intimate partner or family violence are not to be taken lightly, but our concern over damaging forms of aggression overshadows the recognition of constructive forms. There is but one tradition in communication studies that explicitly conceptualizes constructive forms of aggression: Communication predispositions to aggression.

2Communication predispositions to aggression

This body of theory and research has been reviewed in two relatively recent volumes (Avtgis and Rancer 2010; Rancer and Avtgis 2006), although related works exist that parallel this line of theory (e.g., Dailey, Lee, and Spitzberg 2007; Kinney 1994). The basic model conceptualizing communication predispositions to aggression has its roots in personality theory. In particular, it is based on Andersen’s (1987) taxonomy of individual differences or traits that influence communication behavior, specifying “communication predispositions” as a type of individual difference variable. Communication predispositions are an “attempt to understand, measure, or predict stability in an individual’s attitude regarding communication behavior” (p. 50). In a thorough conceptualization taxonomizing aggression, Infante (1987a) begins by defining aggression as any kind of attack – more specifically, the applying of force onto one person by another. He relies heavily on Buss (1961), who defines aggression as a behavioral response delivering pain to another person. After reviewing several traditional treatments of aggression, Infante comes to a working definition:

An interpersonal behavior may be considered aggressive if it applies force physically and/or symbolically in order, minimally, to dominate and perhaps damage or, maximally, to defeat and perhaps destroy the locus of attack. The locus of attack in interpersonal communication can be a person’s body, material possessions, self-concept, position on topics of communication, or behavior. (p. 158)

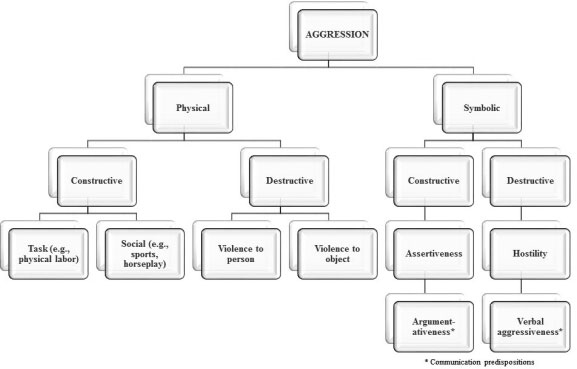

Infante (1987a) proceeds to develop a detailed typology of aggression that neatly categorizes argumentativeness, a subset of assertiveness, as symbolic constructive aggression, and verbal aggressiveness, a subset of hostility, as destructive symbolic aggression. In so doing, he also distinguishes these symbolic forms of aggression from constructive and destructive physical forms of aggression. The typology is consistent with much of the research distinguishing assertive, aggressive, and passive forms of communication (Spitzberg 1994; Spitzberg, Canary, and Cupach 1994). Figure 1 provides a graphic depiction of Infante’s typology of aggression. There are several other established typologies of intimate partner violence (see: Holtzworth-Munroe and Meehan 2004; e.g., instrumental vs. expressive: Hamel, Desmarais, and Nicholls 2007; McEllistrem 2004; Tweed and Button 1998; family-only vs. dysphoric/borderline vs. generally violent/antisocial: Delsol, Margolin, and John 2003; Dixon and Browne 2003; Holtzworth-Munroe et al. 2000; situational couple violence vs. intimate terrorism; Johnson 1995, 2006, 2011), but these are not derived from a communication perspective.

Fig. 1: Infante’s (1987a) typology of aggression.

Infante concedes, and it is apparent from the figure, that human behavior in situ is not so tidily categorized. For example, what he classifies as constructive physical task aggression can be used symbolically to humiliate a co-worker, thus functioning as what the model categorizes as hostility (destructive symbolic aggression). Fundamentally, the model limits the meaning of “symbolic” to “verbal”, although Infante points out the complication of potential multiple meanings (i.e., physical acts may be used symbolically). This model is, however, a useful organizer for our current task, which is to explore the communication competence implications in the literature on verbal and physical aggression.

Argumentativeness is defined as a stable trait that predisposes an individual to defend a position on an issue and verbally attack the positions of others (Infante and Rancer 1982). Moreover, “argumentativeness may be considered a subset of assertiveness, in that all arguing is assertive, but not all assertiveness involves arguing” (Infante 1987a: 164). A person with high argumentativeness enjoys arguing and will eagerly engage in verbal debate; “the individual perceives this activity as an exciting intellectual challenge, a competitive situation which entails defending a position and ‘winning points’” (Infante and Rancer 1982: 72). Conversely, a person low in argumentativeness feels uncomfortable about arguing before, during, and after the event that calls for argument (Infante and Rancer 1982).

Verbal aggressiveness is defined as “the tendency to attack the self-concepts of individuals instead of, or in addition to, their positions on topics of communication” (Infante 1987a: 164). One potential complication of this definition is the lack of thorough conceptualization of self-concept. Given that some perspectives view self-confirmation or consistency of messages with self-concept as important as the valence of such messages, it is possible that negative messages that are consistent with a person’s self-concept could be interpreted as less disruptive than inconsistent positive messages (Dailey, Lee, and Spitzberg 2007). The most common forms of verbal aggressiveness are competence attacks, teasing, and nonverbal emblems (such as hand gestures). Other less common forms include character attacks, background attacks, physical appearance attacks, maledictions, teasing, swearing, ridicule, and threats (Wigley 1998). “Verbally aggressive messages do not contain the dimensions of respect and trust” (Myers and Johnson 2003: 93), and are more common in exchanges where the topic is of great importance and the consequences are very meaningful to those involved. Infante and colleagues (1984) identified four primary reasons individuals are verbally aggressive, including psychopathology (repressed hostility), disdain for the other person, social learning of aggression, and argumentative skill deficiency (not knowing how to argue constructively). Trait verbal aggressiveness may also have biological origins (see Beatty and PascualFerra, this volume), having been associated with asymmetry in the prefrontal cortex (Heisel 2010) and with prenatal androgen exposure (Shaw et al. 2012). It is widely acknowledged that argumentative communication that is not verbally aggressive is competent (e.g., reviews in Avtgis and Rancer 2010; Rancer and Avtgis 2006; Infante and Rancer 1996; Rancer and Nicotera 2006).

2.1Links to communication competence

As fully explicated in the opening chapters of this volume, communication competence is generally defined as the ability to interact successfully (Spitzberg and Cupach 1984), emphasizing a dyadic perspective (Goffmann 1969; Wiemann 1977), goal achievement (Bochner and Kelly 1974), and context (Bochner and Kelly 1974; Hymes 1979; Wiemann 1977). Across traditions in communication competence, the common meaning is clear: “the ability of an interactant to choose among available communicative behaviors in order that he [sic] may successfully accomplish his own interpersonal goals during an encounter while maintaining the face and line of his fellow interactants within the constraints of the situation” (Wiemann 1977:198). Communication competence is thus an outcome (McFall 1982; Spitzberg and Cupach 1984; Spitzberg and Hurt 1987) that can be self- or other-assessed (Parks 1994; Spitzberg 2003; Spitzberg and Cupach 1984).

Spitzberg’s (1983, 1988) central criteria, appropriateness and effectiveness, are implicitly or explicitly echoed in most treatments of communication competence. Appropriateness is defined by social sanctions (Bellack and Hersen 1978; Trenholm and Rose 1981), but avoiding negative sanctions is insufficient without goal achievement, which reflects effectiveness (Canary and Spitzberg 1987; Parks 1977, 1985). Aggressive communication has long been linked to communicator skill. It must be noted at the outset that both argumentativeness and verbal aggressiveness, while conceptualized as predispositions, have been measured and observed as both self-reports of typical behavior and as other-reports of actual or hypothetical behavior. Argumentativeness is linked to competent communication (Onyekwere, Rubin, and Infante 1991), while verbal aggressiveness is seen as less competent, less desirable, and may even be triggered by situational variables to escalate to violence (Sabourin, Infante, and Rudd 1993; Infante, Chandler, and Rudd 1989). The locus of attack in argumentative communication is the opinion or position on a topic; whereas, the locus of attack in verbally aggressive communication is the other’s self-concept. From a pragmatic perspective, argumentativeness can be seen as existing in the content domain, its focus being the issue; whereas verbal aggressiveness exists in the relational domain, its focus being the person. The general conclusion from this program of research is that argumentative communication tends to promote positive outcomes, whereas verbally aggressive communication tends to promote negative outcomes (Rancer et al. 1997).

Early work in the area quickly established the relational outcomes associated with these predispositions. Martin, Anderson, and Horvath (1996) demonstrated no impact of argumentativeness on friendship quality, but noted the hurtful effects of verbal aggressiveness, which were more pronounced as relational closeness increased. Further, Semic and Canary (1997) concluded that verbal aggressiveness interferes with constructive argument production between friends. In dating couples, verbal aggressiveness is likewise shown to be incompetent (Veneble and Martin 1997). In families, the pattern may be slightly different. While they found no effect for levels of verbal aggressiveness, Rancer, Baukus, and Amato (1986) illustrate that asymmetry in argumentativeness (one partner high, the other low) did predict marital satisfaction. Between parents and their children, the impact of verbal aggressiveness is far more damaging. Verbally aggressive parents undermine self-esteem and social competence in their children (Roberts et al. 2009). Parents who are high in verbal aggressiveness are more likely to escalate from frustration to anger than those low in verbal aggressiveness, providing further evidence of the contention that verbal aggressiveness is triggered or moderated by situational factors (Rudd et al. 1998). More disturbingly, children with highly verbally aggressive mothers are impeded as adults in their ability to achieve the emotional support and interpersonal solidarity necessary for fulfilling adult relationships (Weber and Patterson 1997). The impact between fathers and sons is equally concerning. The higher fathers’ verbal aggressiveness, the less socially appropriate both fathers and sons rate their fathers’ interaction plans (Beatty et al. 1996; Rudd et al. 1997). Further, fathers high in verbal aggressiveness are significantly more likely to view corporal punishment, such as slapping, as appropriate (Rudd et al. 1997). Finally, among siblings, verbal aggressiveness predicts low trust, low relational satisfaction, and more destructive teasing (Martin et al. 1997).

Other studies that link argumentativeness and verbal aggressiveness to communicator skill abound (e.g., see reviews by Infante and Rancer 1996 and Rancer and Nicotera 2006). Assertiveness generally is associated with communication competence (Zakahi 1985). Those high in argumentativeness and low in verbal aggressiveness are more likely to engage in collaborative decision-making (Anderson, Martin, and Infante 1998). Related theoretical models, reviewed below, were developed from such links to communicator skill. For example, the theory of independent-mindedness (Infante and Gorden 1987) is based in organizational communication research linking subordinates’ levels of satisfaction with aggressive communication. Infante et al. (1993) found that satisfaction increased as superiors were seen as higher in argumentativeness, lower in verbal aggressiveness, and were more affirming (relaxed, friendly, attentive) in communicator style. Additionally, research concluding that verbal aggressiveness predicts interspousal violence (Sabourin, Infante, and Rudd 1993), and the acquisition of argumentative skill reduces intrafamily violence (Infante, Chandler, and Rudd 1989) yielded the argumentative skill deficiency model. The model essentially proposes that one of the causes of aggression is the lack of more competent, argumentative skills needed to resolve interpersonal conflicts or transgressions.

More recently, Edwards and Myers (2007) demonstrated that students perceive instructors who display high argumentativeness and low verbal aggressiveness as more competent, caring, and credible. Using McCroskey and Richmond’s (1996) competence dimensions assertiveness and responsiveness, Martin and Anderson (1996) found that assertive communicators are more argumentative and that responsive communicators are less verbally aggressive. Similarly, in other research, high argumentatives feel more communicatively competent (Rancer, Kosberg, and Silvestri 1992) and are rated as both more effective and appropriate (Onyekwere, Rubin, and Infante 1991) than low argumentatives. Martin, Anderson, and Thweatt (1998) found that cognitive flexibility and communication flexibility were both positively related to argumentativeness and negatively related to verbal aggressiveness. Frymier, Wanzer and Wojtaszczyk (2008) found that student perception of teacher verbal aggressiveness was positively correlated with the teacher’s propensity to use inappropriate humor (disparaging to others, unrelated to course content, or offensive in other ways). Further, perception of teacher verbal aggressiveness was also negatively correlated with teacher nonverbal immediacy and conversational appropriateness. Student self-report verbal aggressiveness was negatively correlated with student communication competence and predicted their perception that their teachers use other-disparaging humor.

Olson’s (2002) participants felt appropriate when unaggressive and inappropriate when aggressive. They felt effective when achieving calm respectful discussion but identified instances where aggression was appropriate and effective. Although the research rests on an implicit presumption of aggression as destructive, several instances of overt verbally aggressive communication were seen as appropriate and/or effective because they got the partner’s attention, served as a method of self-defense, or were situationally justified. Because Olson neither addresses argument nor differentiates constructive from destructive aggression, her study is not a direct application of the Infante tradition. However, the results do highlight the complexities of aggression in relational conflict.

A tidy conceptualization of argumentative communication as effective and verbally aggressive communication as inappropriate translates poorly across situations, warranting caution in our presumptions. Indeed, studies by Myers and Johnson (2003) and Nicotera et al. (2012) evidenced that high argumentativeness may be considered competent only in particular contexts. Both these studies suggested that high argumentativeness is competent when conflict and advocacy are salient to the situation. In non-confrontational situations, especially those requiring socio-emotional support, low argumentative people are preferred to high argumentative people (Waggenspack and Hensley 1989). Additionally, Martin, Dunleavy and Kennedy-Lightsey (2010) reviewed research that concluded that verbally aggressive communication may be strategically used for mutually beneficial instrumental outcomes.

The association between communication predispositions, aggression, and conflict styles is conceptually simple, and also illustrates the positive outcomes associated with high argumentativeness and low verbal aggressiveness. Most models of conflict style utilize conceptual dimensions concern for issue (or self) and concern for other. The literature conflates concern for issue with concern for self (see Nicotera and Dorsey (2006), for a review.) Issue/self-concern is conceptually related to argumentativeness; other-concern is conceptually (inversely) related to verbal aggressiveness. Achievement of one’s own goals predicts moderate communication competence, but sensitivity to the partner’s goals predicts both appropriateness and effectiveness (Lakey and Canary 2002).

Linking conflict style to Duran’s (1983) measure of communication competence, McKinney, Kelly, and Duran (1997) found self-orientation was less competent than concern for issue (related to argumentative communication) and concern for other (inversely related to verbally aggressive communication). Gross, Guerrero, and Alberts (2004) found solution-oriented conflict style (high concern for both issue and other) was more effective and appropriate according to both self- and other-ratings. Nonconfrontive style (low on both concerns) was lower on both effectiveness and appropriateness dimensions in both self- and other-ratings. In contrast, the controlling style (high on concern for issue, low on concern for other) was effective in self-ratings, but neither effective nor appropriate in other-ratings. It must be emphasized that the conflict styles operationalization does not differentiate well between self- and issue-concern, so the distinction between types of aggression is muddied. However, it is clear that different patterns of aggressive behavior in conflict yield similar patterns in competence ratings: argument tends to be seen as effective, and hostility as inappropriate.

2.2Related theoretical models

A number of theoretical models have been derived from the communication predispositions to aggression tradition – three that relate most directly to communication competence. The theory of independent-mindedness (Infante and Gorden 1987) applies the presumed competence of highly argumentative and low verbally aggressive communication to organizational management and organizational culture. The argumentative deficiency model (Sabourin, Infante, and Rudd 1993) has been applied to abusive marital relationships and to adolescent communication. Finally, a general model of argumentative competence has been posited (Nicotera et al. 2012).

2.2.1.Theory of independent-mindedness: The constructive combination

The theory of independent mindedness (TIM) is grounded in the presumption that organizational theory and practice should be based in the assumptions of the larger society. Hence, TIM is a prescriptive theory of U.S. management practice (see Rancer and Avtgis 2006 for a thorough overview.) Infante (1987b) observed that participatory models of management that were popular at the time were as antithetical to American culture as the top-down authoritarian practices they were intended to replace. The prevalent corporatist model (Derber and Schwartz 1983) endorsed participatory management practices seeking to promote collectivist models of decision-making that minimized power and status differentials. However, Infante (1987b) pointed out that while American culture promotes self-determination, autonomy, and individual rights, most notably the right to free expression, the culture also promotes power and high-status positioning as a sign of individual achievement. TIM, therefore, promotes a supervisor/subordinate dialectic that emphasizes power and status differences at the same time that it promotes respect and affirmation of the employees’ value and, especially, employee voice.

Employee voice refers to the assertion of arguments, grounded in good reasons, for organizational change and job modifications and is grounded in employee commitment to organizational goals and corporate commitment to product and work life quality (Gorden, Infante, and Graham 1988; Gorden, Infante, and Izzo 1988). TIM predicts that when both supervisors and subordinates are high in argumentativeness, low in verbal aggressiveness, and communicate in affirming styles that are relaxed, friendly, and attentive, then subordinates will be more highly committed to the organization, more satisfied, rated more highly on their performance by their supervisors, and more effective in their upward communication than any other combination of communication traits (Infante and Gorden 1987, 1991). The most competent combination of aggressive communication is, once again, high argumentativeness and low verbal aggressiveness.

While TIM, as a theoretic construction, is not widely cited, current management practices reflect its claims, and other work continues to support its predictions. For example, Kassing and Avtgis (1999) examine the influence of verbal aggressiveness and argumentativeness on organizational dissent. Articulated dissent is open, clear, and aimed at internal audiences who can influence policy. Articulated dissent is the very essence of employee voice as it is encouraged by TIM. Latent dissent is frustrated ineffectual expression lacking sufficient avenue. Displaced dissent is expression to external personal (rather than media or political) audiences. Articulated dissent might be seen as both effective and appropriate, latent and displaced dissent as ineffective. Low verbal aggressiveness and high argumentativeness predict articulated dissent, and high verbal aggressiveness predicts latent dissent.

There is also some evidence that TIM is applicable to family communication. Research suggests that parental communication high in argumentativeness and low in verbal aggressiveness is less likely to be associated with corporal punishment (Kassing, Pearce and Infante 2000; Kassing et al. 1999) and more likely to be associated with open communication characterized by free and more satisfying communication (Booth-Butterfield and Sidelinger 1997). Moreover,

[f]amilies labeled as “pluralistic” are characterized by high levels of conversation and low levels of conformity. This combination creates an open and unrestrained family environment which all family members feel free discussing a broad range of topics. Such an unrestricted communication climate fostered the communication competence of all family members, especially children. (Swanson and Cahn 2009: 143–144)

These findings continue to support the conclusion that highly argumentative communication that is low in verbal aggressiveness is most competent.

2.2.2.Argumentative skill deficiency model: The destructive combination

The argumentative skill deficiency model predicts that verbal aggressiveness is most likely to escalate to physical aggression in the absence of effective argumentative skills (Infante, Chandler, and Rudd 1989; Infante et al. 1990; Sabourin, Infante, and Rudd 1993). In brief, if a person has the skills to resolve conflicts through discursive use of argumentation, there is little need for more coercive means, such as verbal aggression. Previous research supports this contention, physical aggression being commonly employed during compliance-gaining episodes (Deturck 1987). Marital quality is associated with low verbal aggressiveness and high argumentativeness (Payne and Sabourin 1990). Verbal aggressiveness appears to be a necessary, but not a sufficient condition for violence. Other factors, such as financial stress, drug/alcohol use, and self-esteem, trigger latent hostility that then escalates to physical violence.

Indeed, interspousal violence is associated with high levels of verbal aggressiveness (Infante et al. 1990), especially in patterns of negative reciprocity (Sabourin 1995). As compared to distressed but nonviolent couples and to nondistressed couples, violent couples exhibited significantly higher levels of verbally aggressive messages and reciprocal cycles of verbally aggressive behavior (Sabourin, Infante, and Rudd 1993). These studies confirm the supposition that violent and abusive couples lack argumentative skills. However, the question of whether training in argument skill might then reduce violence has not been directly tested from within this tradition. Although interventions that build argument and conflict skills are a therapeutic standard and are often found to be effective (Markman et al. 1993; Rappleyea, Harris, and Dersch 2009; Tutty, Babins-Wagner, and Rothery 2006), some scholars question whether the training of individual skills is sufficient to alter relational patterns as deeply rooted as intimate partner violence (Whitchurch and Pace 1993).

The argumentative skill-deficiency model has also been applied to adolescents (Rancer et al. 1997), under the assumption that verbal and physical aggression might be reduced by argumentative skills training. However, although Rancer et al.’s (1997) training program for 7th grade students did indeed increase argumentative skill, increasing the students’ effectiveness in situations requiring argument, and making them feel more effective, both the immediate and longitudinal (8th grade) measures (Rancer et al. 2000) revealed no concomitant decrease in their verbal aggressiveness. Further calling into question the direct applicability of the argumentative skills deficiency model to adolescents, Roberto (1999) found that among 7th grade boys, those who had been suspended for fighting the previous year were significantly higher in verbal aggressiveness than those who were not, but argumentativeness did not predict fighting. Further, O’Neill, Clark, and Jones (2011) did find that conflict resolution training reduced levels of aggression in fourth-grade students. It must be noted, however, that trait argumentativeness and skills for producing argumentative messages are not precisely the same thing, so these results merely call our presumptions into question, warranting further research on the argumentative skills deficiency model, particularly in light of the clinical literature on communication training programs for the reduction and prevention of intimate partner violence.

Later research rooted in this tradition (e.g., Sabourin and Stamp 1995; Stamp and Sabourin 1995) turned to qualitative methods and expanded beyond couples to families (see Cahn (2009) for a number of reviews that document and extend the impact of the argumentative skills deficiency model on the field’s research of intimate partner and family violence). Research (reviewed below) has also expanded from an individual skills deficit presumption to approaches at the family system level that examine communication patterns associated with verbal and physical abuse.

2.3Aggression competence model

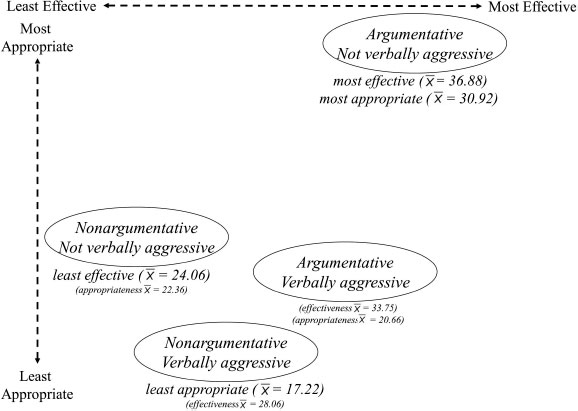

Given the evidence that argumentativeness is considered competent on the effectiveness dimension and verbal aggressiveness is considered incompetent on the appropriateness dimension, Nicotera et al. (2012) sought to cross-validate the conceptualization of the two forms of aggression (the Infante tradition) with the conceptualization of effectiveness and appropriateness dimensions of competence (the Spitzberg tradition). An aggression competence model was posited for testing, wherein the four combinations of high and low argumentativeness and verbal aggressiveness were aligned with Spitzberg’s (2000) four quadrants of communication competence (high and low on effectiveness and appropriateness). The most competent communication, both effective and appropriate, is optimizing, hypothesized as argumentative communication that is not verbally aggressive. The least competent communication, neither effective nor appropriate, is minimizing, hypothesized as verbally aggressive communication that is non-argumentative. The other two combinations match with Spitzberg’s typology as follows: communication that is argumentative and verbally aggressive is aligned with Spitzberg’s maximizing, effective but inappropriate; communication that is neither argumentative nor verbally aggressive alliance with Spitzberg’s sufficing, appropriate but ineffective. Nicotera et al. (2012) operationalized levels of aggression dichotomously with manipulation-checked hypothetical scenarios of an interaction, consisting of an individual who needs to address a complaint about a roommate’s messiness. The communication competence dimensions (i.e., appropriateness and effectiveness) were measured with Canary and Spitzberg’s (1987) rating scales.

The hypothetical scenario was contextualized as the individual feeling frustrated with the roommate’s lack of cleanliness and desiring to confront that issue when the two sat down to study together. Hence, the actor’s goal of confronting a controversial issue was constant in all variations of hypothetical conversations. Results supported the hypothesis that argumentative communication that is not verbally aggressive is the most effective and appropriate of all combinations. However, results also showed that in ratings of non-competent combinations, argumentative and verbally aggressive communication interact differently in their effects on effectiveness and appropriateness. Specifically, the least effective combination was nonargumentative communication that was not verbally aggressive; whereas, the least appropriate behavior was nonargumentative but verbally aggressive communication.

Fig. 2: Nicotera et al.’s (2012) Revised Aggression Competence Model. Reprinted with permission.

By holding the hypothetical scenarios constant to a situation requiring argument, the appropriateness of argument behavior was predetermined and was thus reflected in participants’ ratings. One component of appropriateness ratings is the suitability of utterances to the situation. For the explicit goal of confronting an issue of disagreement, argument is generally more appropriate than non-argument. Nicotera et al. (2012) proposed an alternative aggression competence model for situations requiring argument that splits non-competence in the way suggested by the data (see Figure 2.) In this study verbally aggressive communication that was not argumentative was more effective than communication that was neither aggressive nor argumentative. It seems, therefore, that in situations requiring argument, some degree of aggression may be better than none.

In hindsight, this is a logical flaw in the hypothesized aggression competence model. The contention argumentative communication that is not verbally aggressive is most competent presumes a situation in which argument is called for. Therefore, we still have no explanation of the competence required to know when argument is called for. We might think of this as competence in assessing situational requirements. In other words, the enactment of communicatively competent behavior relies upon the assessment of what behavior would be effective and appropriate in any given situation. This logical flaw in the research underscores the importance of context in determining communication competence. Obviously, hostility is inappropriate in any interpersonal exchange. However, the appropriateness of argument varies according to the situation. A full conceptualization of aggression competence, then, would explicate it as communication of a nonhostile nature that applies argument effectively in situations where argument is called for, and refrains from argument in situations where it is inappropriate. By way of fully understanding verbal aggression and violence, it is important to explicate the related construct of argumentative skill.

Hample (2003) offers a review of arguing skill that provides a partial answer to the question of explaining competence in assessing situational requirements. The concept of argumentative competence from this tradition (Hample 2005; Hample and Dallinger 1987; Hample, Sells, and Inclán Velázquez 2009; Hample, Warner, and Norton 2006; Trapp, Yingling, and Wanner 1987; Wenzel 1980) is conceptually grounded in O’Keefe’s (1977) distinction between argument1 and argument2. Argument1 refers to a logical construction giving reason with evidence, as in, “I offered good arguments to my mother as to why she should let me borrow her car.” Argument2 refers to an interactional exchange, as in, “I argued (had an argument) with my mother about borrowing her car.” In this sense, Hample’s argumentative competence, which adds argument0, the cognitive process of argument (Hample 1985), is not grounded in the conceptualization of argument as a form of aggression. Argument, in this alternative tradition, is defined as reason-giving with any references to aggression presuming aggression-as-hostility. Hample (2003) offers an answer to the question of the competence required to assess situational requirements for argument. He identifies three possible intersecting frames that ordinary actors have for the activity of interpersonal arguing, with the presumption that competence is dependent on goal-direction. To assess competence, therefore, we must know what the actor is trying to accomplish.

The first frame is primary goal – the substantive reason for engaging in argument2. There are four possible goals: to resolve an issue (utility frame), to establish dominance, self-presentation (of skill or ability), and recreation. So, a person can argue with his or her mother to borrow her car, argue with a son to show him who is boss, argue with a boss to illustrate command of the situation, or argue with a sibling about politics for the sheer fun of it. These goal types, of course, might not be exclusive. For example, the issue in need of resolution may be who is in charge (dominance), and to resolve that issue command (or not) of the situation at hand needs to be established. Each of these four possible goals carries with it different standards for what constitutes success, and therefore competence. For all four primary goal frames, hostility (verbal aggressiveness) would be considered non-competent, and considerations of social appropriateness will vary by relationship type and power dynamic. The dominance goal, however, is identified as the one most at risk to engender reciprocal destructive aggression. According to Hample (2003) to be argumentatively competent, the actor must be clear about their reasons for arguing and must be able to perceive the other person’s reason for arguing and respond accordingly. Any of the four types of goals may be legitimate, but each places different restrictions on what constitutes competent argument.

Hample and Cionea (2010) present data that reveals all of these frames to be significantly correlated with both verbal aggressiveness and argumentativeness. Specifically, a utility frame is weakly associated with verbal aggressiveness (r = .15) and strongly associated with argumentativeness (r = .40); a dominance frame has the opposite pattern, strongly associated with verbal aggressiveness (r = .43) and only weakly associated with argumentativeness (r = .15). Both identity and play frames are moderately associated with verbal aggressiveness (in both cases, r =.24) and strongly associated with argumentativeness (identity r = .44, recreation r = .66).

The second frame is connecting with another’s goals, coordinating one’s own objectives with those of others, with three types of connection. First, those who do not make much effort to connect their goals with those of others will likely never argue competently, unless it is by accident. The two fundamental ways of connecting to others is competitively or cooperatively, which is a common distinction in many theoretic traditions on conflict and argument. Hample (2003) points out that each leads to a different form of argument as defined in the Aristotelian tradition. Eristic (competitive) arguing is fighting, seeking to win through the other’s loss – which may be well-mannered or hostile. Formal traditions of arbitration, for example, are eristic without being socially inappropriate. In interpersonal relations, however, eristic arguing takes the form of meeting one’s goals by defeating the other’s, which is generally bad for a relationship. Relationally, attempting to get what I want by squashing my spouse’s aspirations would not generally be considered competent argument. Coalescent (cooperative) arguing, on the other hand, is more constructive in acknowledging the goals of the other, with an attempt to maximize mutual gain. Only coalescent argument might be considered interpersonally competent.

Hample and Cionea’s (2010) data do not match Hample’s (2003) schema perfectly, but they do report that blurting – verbalizing without regard to others – is moderately related with verbal aggressiveness (r = .34), but the correlation with argumentativeness is nonsignificant (Hample and Cionea 2010). Further, a cooperative frame is strongly negatively correlated with verbal aggressiveness (r = −.44) and weakly negatively correlated with argumentativeness (r = −.17); wheras, a civil frame is negatively correlated with verbal aggressiveness (r = −.21) and positively correlated with argumentativeness (r = .25).

The third frame ordinary actors apply to interpersonal argument is reflecting on the experience of arguing. Hample (2003) cites copious research illustrating that ordinary actors see eristic argument (fighting) as arguing; whereas coalescent argument is seen as discussion. This fundamental observation was, in fact, the basis for some of my own research, investigating the social desirability of terminology in the argumentativeness scale (Nicotera 1996). Hample (2003) also reviews research revealing that people closely associate “argument” with violence, counter to scholarly understandings of argument as rational, evidence-based reason-giving. Hample and Cionea (2010) report that a measure of professional contrast (indicating the extent which the respondent’s naïve theory of argument is similar to that of argumentation scholars) is moderately negatively correlated with verbal aggressiveness (r = −.21) and moderately associated with argumentativeness (r = .20).

In the end, Hample (2003) concludes that argument is not an individual activity, but is interactive. Competent interpersonal argument, therefore, is relationally defined and relationally contextualized. Competent argument, furthermore, is embedded in competent conversation with all that this entails. While the argumentative competence tradition (as represented here by Hample) implicitly presumes aggression to be equivalent with hostility, this is more terminological than conceptual. If we conceptually define argument as a constructive form of aggressive behavior, the claims made in the argumentative competence tradition still hold.

It is clear from research in the Hample tradition that both hostility and conflict avoidance are noncompetent and that competent argumentation is framed in particular ways by actors. It is clear from the research in the Infante tradition that hostility is destructive, that argumentativeness is constructive, and that high argumentatives have positive beliefs about argument, value argument and reason in the face of controversial issues, will seek to engage in such activity, and will enjoy it. It is not clear, however, what set of competencies comprise the ability to know when it is appropriate to argue. We do not know what distinguishes those who are able to identify situations that require argument from those who cannot. From the Hample tradition, we know that such distinction is a crucial component of argumentative competence. For aggression competence, then, one should not only argue well with no verbal aggressiveness (hostility), but should know when to engage in argument and when to refrain.

3Related research on aggression and competence

When it comes to aggression, it is tempting to define competent communication by what it is not. The communication competence literature would suggest that competent communication achieves goals and is neither feeble nor hostile, neither supporting nor affiliating with physical violence. However, citing numerous research studies, Spitzberg (2010, 2011) points out that violence can be seen as competent when it is justifiable. In addition, “there are conditions in which violence is viewed as ‘having its place’” (Spitzberg 2011: 343). Although people generally disapprove of violence in general, it is viewed as appropriate in such situations as “self-defense, in defense of a child, in response to being hit, and in response to a partner’s sexual infidelity … in being playful or seeking revenge … and as an indicator of the perpetrator’s love” (p. 343). In short, with copious research to substantiate the claim, Spitzberg (2010, 2011) concludes that the role and value of violence in relationships is negotiated, rather than fixed. We might conclude, then, that a competent communicator gets things done – socially appropriately to context – and maintains relationships without being a doormat, but that “social appropriateness” is not necessarily nonviolent. It is context that determines whether verbal or physical aggression is competent communication.

The determination of what to include in a review on communication competence and aggression is difficult, as there is, unfortunately, a large set of sizeable literatures on all manner of unmannered behavior among people. Workplace bullying, for example, does not resemble competent communication: “repeated, health-harming mistreatment that takes one or more of the following forms: verbal abuse; offensive conduct and behaviors (including nonverbal) that are threatening, humiliating, or intimidating; or work interference and sabotage that prevent work from getting done” (Lutgen-Sandvik, Namie, and Namie 2009: 27). When the interactive goal is to hurt another, such an actor cannot be assessed as communicatively competent, regardless of how good she is at using communication to harm others, but she also cannot fully be defined as noncompetent if she is skillful at meeting her goal of doing harm. Similarly, when aggression is physical, such as in cases of intimate partner violence (IPV), the acts of violence may meet the goal of dominating or harming another and may even be considered competent by the recipient and/or observers, depending on context (Spitzberg 2010, 2011). Without knowing the actor’s goals and the negotiation of meaning in the context, or in cases when harm may be a proximal or instrumental goal in the service of a more terminal or distal goal, broad conclusions become more difficult. Even in severe acts of IPV that injure the victim, a tidy definition of such behavior as noncompetent is conceptually problematic if the actor is skillful at doing harmful things intentionally while maintaining the relationship. For instance, male IPV perpetrators’ interpersonal skills to convey caring and accomplish positive acts actually mediate the impact of abuse on their partners’ relational satisfaction (Marshall, Weston and Honeycutt 2000). In fact, many victims of IPV are relationally satisfied (Spitzberg 2010).

One problem is that assessments of competence rely on an implicit presumption of fundamental ethics (Spitzberg and Cupach 2011) and of normal mental health. Communication is competent to the extent that it meets both the actor’s goals and the standards of social appropriateness, but what is implicit is that we assume these goals to be ethical communication goals grounded in a value for the ethical treatment of others – which are conceptually captured by effectiveness and appropriateness – and we culturally define ethical treatment as non-harming. Spitzberg and Cupach (2011) also point out that some behavior may present itself as inappropriate but that often such means are necessary and even desirable in the end.

In addition, there are unexplored but fundamental distinctions between Machiavellian unethical communication (harmful to others yet very skilled) and unskilled communication that harms others through ineptitude or anger. Although both kinds of behavior have harmful effects, they have different origins. The distinction is both of intent and affect. Intentional harm to others because of anger seems to be explainable as an incompetent form of communication. Intentional harm in the absence of anger, however, seems outside the presumptions of communication competence theory (although, see: Canary, Spitzberg, and Semic 1998). When people consciously and dispassionately harm others because they want to or because it is a means to an end for themselves, this kind of aggression seems outside the scope of communication competence theory. There is an implicit assumption among communication competence scholars that people behave badly because they do not know any better or because anger is out of control. There is a long-held assumption among psychologists studying human aggression that conflict engenders aggression in the presence of anger (Buss 1961; Geen 1998). However, this set of presumptions does not explain dispassionate acts of aggression that harm others for personal gain.

A second class of behavior that seems unexplainable with a communication competence approach is that caused by mental illness or psychiatric disorder, such as intermittent explosive disorder, where verbal and physical aggression are out of the actor’s control (e.g., McCloskey et al. 2008). Those with sociopathic and psychopathic disorders harm others because they either do not have the capacity to care or are actually seeking to do harm. Such behavior is also beyond the scope of a communication competence explanation.

Communication competence is simply not a good explanation for intentionally harmful behavior, or for behavior with conscious and/or organic disregard for others (although, see Felson 1984; Gergen 1984; Mummendey, Linneweber, and Loschper 1984; Olson 2002; Spitzberg 2011). Such conditions work contrary to the basic concept of appropriateness in most normal circumstances. If an actor harms another, is aware of that harm, and has no regret or negative self-judgment because of it, then the communication competence model is simply not a good explanation. In fact, it is communication competence that actually assists some abusers in maintaining their relationships despite their harm to the partner (Marshall, Weston, and Honeycutt 2000). Communication competence seems a more appropriate approach to explain the behavior of those actors who harm others, and even themselves, because they are unskilled. These people may be unaware of the harm, surprised by it, regretful of it, or confused by it, but when faced with the knowledge that they have harmed, they will justify, excuse, minimize, or deny it (Stamp and Sabourin 1995), perhaps from a fundamental principle that harming others is not ethical.

For example, Bingham and Burleson (1996) found that college males with a proclivity for sexual harassment were more apprehensive about and suspicious of dating, less satisfied with their dating experiences, more anxious about communication, and found communication less rewarding. All of these communication difficulties associated with sexual harassment proclivity are related to communication competence. Some people may be prone to sexual harassment because they are bent on harming their targets; others are simply bumbling without the skill to interact appropriately (who might not even acknowledge their own wrongdoing). It is this latter type of aggression that is of interest here because it is linked to incompetence. The remainder of this chapter will examine literature on verbal and physical aggression conducted outside the Infante tradition that is relevant to such incompetent communication – linked to a lack of communication skill, rather than to intentional harm or disregard due to some pathology or fundamentally evil nature of the actor.

Aggression scholars from other disciplines tend not to ascribe to the Infante tradition that recognizes argument as a constructive form of aggression. Assertiveness and aggressiveness tend to be examined as distinct phenomena. Hence the term aggression is used with an inherently negative connotation, and the term verbal aggressiveness is common but does not subscribe to the theoretic or operational structures in the Infante tradition, even though the phenomenon itself is similar. To avoid confusion, in the discussion of this literature the term verbal aggression will be used. The role of verbal aggression in various relational contexts reveals the roles it plays in these contexts.

3.1Verbal aggression

While there is a general presumption that verbal aggression represents a non-competent form of communication, there is a great deal of variation in opinion about its sources and solutions. Researchers taking a biological approach to communication traits have examined the links between verbal aggression and brain activity, in particular the level of symmetry in the prefrontal cortex (Harmon-Jones and Allen 1998; Harmon-Jones and Siegelman 2001; Heisel 2010). Yet, Pence et al. (2011) failed to predict verbal aggression in a meta-analysis across a large corpus of such published studies. Understanding verbal aggression as situational or dispositional, or some combination of both, is crucial to developing interventions to mitigate its expression and prevent its escalation into physical violence.

3.1.1.Anger

Psychologists studying human aggression conclude that communication frustrations and transgressions often provoke conflict and anger (Cahn 1996; Whitchurch and Pace 1993), and that anger escalates to verbal aggression, which, in turn, escalates to physical aggression (Winstok 2006), although neither of these latter escalations is inevitable (Winstok, Eisikovits, and Karnieli-Miller 2004). Guerrero (1994) identified four modes of anger expression in personal relationships. Integrative-assertion is direct and nonthreatening, focuses on honesty, is empathic, and conveys special concern for the partner’s feelings, needs, and viewpoint. This mode of anger expression focuses on mutual goals. As the only mode identified to be constructive and prosocial, integrative assertion represents communicative competence and has a positive impact on relational satisfaction. This mode of anger expression prevents escalation of anger into aggression. Distributive aggression is both direct and threatening, displays a lack of respect for the partner, and may be abusive, intimidating, or physical. Passive aggression is indirect and threatening to the relationship and is often nonverbal (e.g., dirty looks, cold shoulder, withholding affection, etc.). Finally, nonassertive-denial is indirect and nonthreatening. Although this kind of anger expression is nonaggressive, it is also nonassertive and thus represents incompetent communication that damages relational satisfaction. As previously discussed, (see Figure 1) Guerrero (1994) also points out that our understanding of aggression and anger in relationships is incomplete without assessment of non-assertive, noncompetent communication.

3.1.2.Children’s aggression

Given the devastating effects that escalating cycles of aggression can have on individuals, relationships, and families, studies of children’s aggression represent an important body of research. Many scholars believe that childhood aggression impedes the development of effective communication skills and escalates into adulthood, making early identification and intervention imperative (O’Neill, Clark, and Jones 2011). Dumas, Blechman, and Prinz (1994) link low levels of communication effectiveness to social and affective problems associated with aggressive children. They found that aggressive children had less effective communication skills and more disruptive communication, and were more likely to be rejected by their peers and to experience depressive symptoms than their nonaggressive peers, even after differences in peer status and affective functioning were controlled.

3.1.3.Intimate partners

Research on adult interpersonal aggression has examined discrepancies in the ways in which intimate partners perceive their conflicts. In an Israeli population of intimate partners, for example, Winstok (2006) investigated how divergent perceptions of conflict motive and conflict subject, and length of cohabitation, impact expressions of verbal aggression. The unit of analysis was the couple, and hypotheses were tested using couples who had reciprocal aggression with no gender effects. Couples’ divergent perceptions of conflict subject and motive (“What are we fighting about and why?”) are associated with one another and both amplify mutual aggression. Perception of conflict motive has a stronger effect on verbal aggression than does perception of conflict topic. Duration of cohabitation has a moderating effect on divergent perceptions of conflict subject and on mutual verbal aggression. This study illustrates that aggression between intimate partners is relational rather than individual in origin. The communication implications of this study lie in the inability to achieve a shared meaning and understanding of couples whose conflicts escalate to mutual aggression. Presumably, couples who accomplish a shared understanding of the subject of the conflict and of their own and each other’s motives for pursuing it will avoid the anger that escalates into verbal aggression and potentially into physical aggression.

3.2Physical aggression

Because it is considered more severe than verbal aggression, most research focuses on the more pressing and damaging problem of physical aggression, particularly among intimate partners and family members. However, verbal aggression has been shown in numerous studies to be more damaging, with more far-reaching impact than physical aggression (Spitzberg 2010). For this reason, research that focuses solely on verbal aggression has been reviewed separately. However, most research on physical aggression also includes a consideration of verbal aggression.

3.2.1.Children

Demonstrating the fundamental roots of communication competence in skillful use of language, in an Australian sample of incarcerated youth, Snow and Powell (2011) found that interpersonal violence was linked to poor competence in oral language. Spitzberg (2010) reviews copious research documenting that abused children grow up to become abusers, and Shadik, Perkins, and Kovacs (2013) demonstrate that this abusive behavior likely begins in childhood among siblings of abusive and neglectful parents, whose poor communication skills provide a model resulting in sibling violence. Winstok, Eisikovits, and Karnieli-Miller (2004) revealed that children’s images of family members and themselves are disrupted by their fathers’ aggression toward their mother. In conditions of mild aggression, children identify with the aggressor; however, with severe aggression, they identify with the victim. These disruptions in images of family and self motivate children’s own aggression and violence. Further, this study suggests that family violence is motivated by a combination of positive self-image and negative other-image. It is generally demonstrated in the literature that poor communication competence is both a cause and effect of parents’ verbal and physical abuse of children, and that such cause/consequence self-reflexive cycles are inter-generational (Roberts et al. 2009; Swanson and Cahn 2009) and not always unidirectional (Brule 2009).

3.2.2.Intimate partners

Spitzberg (2010, 2011), in a thorough review of research, firmly established that the stereotype of male partners abusing female partners is a myth; female abuse of males and abuse between same-sex partners are equally prevalent. Even so, the majority of literature focuses on males abusing females, particularly in marriages. The competence implications in all of this literature are fairly obvious. Couples in abusive relationships have poor communication and poor problem-solving skills. However, the relationship between competence and violence is nonlinear. Poor communication competence is both a cause and a result of relational violence (Spitzberg 2009; Weaver and Clum 1995; Winstok 2007). Further, there is evidence that communication training, particularly that which focuses on systemic relational patterns of communication rather than individual skills, is effective in reducing relational violence (Dailey, Lee, and Spitzberg 2013; Spitzberg 2013; Winstok 2007).

Sabourin (1995), in a qualitative study, establishes that IPV is most likely when the couple has a mutually domineering pattern with neither partner relinquishing control to the other, so that their interaction is a series of one-up moves, each against the other. This pattern of escalating competitive symmetry represents a lack of communication competence. She also links this pattern to argumentative skill deficiency, enriching the understanding of argumentative skill deficiency by elevating it to the relational system level, rather than presuming that skill deficiency lies within the individual.

When examined at the dyadic level, the differences in communication competence between abusive and nonabusive couples are striking (Sabourin and Stamp 1995). Abusive couples are more vague and less precise in their language, more oppositional and less collaborative in their conflicts, and more ineffective in attempts to achieve goals. Abusive couples are more likely to engage in talk that is relational rather than content-focused. Their emotional tone contains more despair, as opposed to the optimism of nonabusive couples. Abusive couples accomplish their interdependence by interfering with one another as complaints, rather than facilitating one another’s complaints as nonabusive couples do (Sabourin and Stamp 1995).

IPV is more likely under conditions of relational threat. Hannawa et al. (2006) found that relational proprietariness and entitlement, which have been theoretically related to IPV in a number of studies, predicted both instrumental and expressive aggression and were related to self-esteem and attachment. The theoretic explanation is that face threat reactivity stimulates proprietary relational orientation and sexual entitlement, which increases the risk of IPV. They also point out that communicative aggression is far more complex than simple verbal aggression. In addition to verbal hostility, yelling, name-calling, and profanity, abusers also restrict freedom, engage in behaviors that put the other at risk, assert dominance in degrading ways, threaten the victim’s valued resources, isolate the victim, humiliate the victim, make the victim feel insecure about the relationship, withdraw, withhold affection, and generally dominate and control.

Smith (2011) examined the perceptions of abusers who had voluntarily completed an abuser schema theory (AST) intervention. AST teaches abusers to identify the triggers for their abuse, become more aware of these triggers, recognize their physiological arousal and resultant cognitive and behavioral responses, and alter those responses. After completing the therapy, abusers reported a reduction in their anger, an increase in the communication and assertiveness skills, an increase in their propensity to think before they act, and a greater sense of personal power.

Spitzberg (2010) proposed an interactional model for IPV, based on the assumptions that conflict threatens face, face threat evokes defensive tactics that escalate intensity and create mutual face threat, and that these escalating emotions become hazardous and result in rage and violence. First, intimate violence evolves from intimate conflicts. Second, intimate conflicts are about transgressions. Third, transgressions evoke negative emotions. Fourth, negative emotions escalate conflict severity. Fifth, the course of conflict depends on the interactants’ competence. Sixth, communicative aggression increases the risk of IPV. Regarding competence, the most damaging skill deficiencies are attributional divergences, where the partners cross-blame; incompetent account-giving, which increases the severity of conflict escalation; incompetent demand-withdrawal patterns, where withdrawal is a power move that increases frustration and sets the stage for explosive conflicts.

Spitzberg (2011) expands these claims to theorize IPV as a process of personal affect and identity negotiation (PAIN). The PAIN model presupposes that perceived transgressions cause face threat, which caused negative arousal, which cause conflict. Conflict escalation, then, is moderated by defensive attributions and competence perceptions, and finally conflict escalation increases the likelihood of IPV. First there is a perceived affront, resulting from infidelity, estrangement, or other perceived transgressions. This results in negative arousal, most commonly anger, shame, and jealousy. This negative arousal is further impacted by damaging intentional attributions and account (in)competence. Both negative arousal and account (in)competence result in verbal conflict and attributional divergence, which in turn both impact further difficulties in account competence, communicative aggression, and rage which combine to escalate IPV. Spitzberg and colleagues (Dailey, Lee, and Spitzberg 2007, 2013; Spitzberg 2009, 2010, 2013) discuss the interactional processes in which IPV is embedded, conceptualizing that IPV is a form of communication that is part of the overall relational pattern. IPV occurs in a relational context.

The broader interaction patterns within which IPV occurs comprise communicative aggression and psychological abuse. Thus, communicative aggression and IPV are reciprocal with one another, although IPV is likely to be more episodic and chronic, and most IPV is relatively mild. As previously discussed, IPV may even be considered competent. This conceptualization of IPV as a form of communication embedded in relational patterns provides a compelling argument that relational aggression and IPV are highly complex and self-reflexive.

Babcock and colleagues (1993) find that a husband’s physical violence is more likely when the couple is caught up in a demand-withdrawal cycle with the husband in the demand position. This common marital unwanted and repetitive negative cycle commonly casts the woman in the demand position, and was initially labeled the nag-withdrawal cycle. However, this pattern is seen in intimate relationships of all gender compositions, and desire for change rather than gender predicts which partner occupies which position (Holley, Sturm, and Levinson 2010).

Gender stereotypes and stereotypes of marital power positions commonly hold that the woman will be in the demand position. Hence, Babcock et al.’s (1993) observation that male violence is most likely in a marriage with a husband-demand/wife-withdraw pattern suggests that there may perhaps be a dual perception of non-competence. First, getting caught up in the cycle is frustrating; second, being cast against gender-role may make it doubly so. Given what we know from other research about the escalation of frustration to anger to aggression to violence, this may be a competence-based explanation for this pattern. Male violence is associated with unilateral verbal aggression, mutual verbal aggression, a demand-withdrawal pattern with the male in the demanding position, a low proportion of constructive to destructive communication, a lack of mutual problem-solving, poor problem resolution, and more emotional distance after arguments (Feldman and Ridley 2000). Further, Lloyd and Emery (2000) substantiated the claim that violent couples lack relational maintenance skills and that violence is, indeed, predicted by argumentative skill deficiency (Lloyd 1999). Lloyd and Emery (2000) also found that intimate violence is sustained by a dominance-control pattern, especially when cultural frames support relational aggression. Winstok (2007) provided a thorough theoretic structure that embeds IPV in interactive, relational, and societal context, conceptually establishing that IPV is neither an individual nor a behavioral problem. His integrative structural model of violence proposes that society and culture frame the nature of relationship between attacked and attacker, which in turn frames the event that frames the violent behavior. Violent behavior is defined by motives, action, and consequence which are, in turn, driven by purpose, means, and intent. The model is at once intricately complex and elegantly simple. IPV is highly complicated set of issues grounded in personal histories, relational patterns, societal frames, and situational motives and consequences. What is clear is that the relationship between aggression and competence is neither linear nor bivariate. IPV is multilayered, contextual, and is reciprocally and causally related to non-competence in both the aggressor and victim.

Is aggressive communication noncompetent? Not entirely. Argumentative communication can be considered a form of aggression and, in the context of situations requiring argument, should be considered a category of communication competence. While it is clear what constitutes good argumentative skill, it is unclear what constitutes the competence to evaluate which situations require argument and which do not. The links between harmful communicative aggression and communication competence are likewise unclear. In numerous publications, Spitzberg has argued that a dichotomous consideration of nonaggression as good and aggression as bad is, at the very least, shortsighted. Given that the determination of competence must be judged by an observer embedded in the situation, the fact that ordinary people have reported numerous situations in which aggressive communication, and even violence, are justifiable and competent should give us great pause as scholars. Our simple presumption that doing injury (physical or otherwise) to a relational partner is bad simply does not resonate with the reports of ordinary people. In addition, communication competence models are unsatisfactory for understanding communication that is motivated by conscious intent to do harm. Competence explanations either need to be expanded or supplemented by alternative explanations for such behavior. Communication competence seems a more appropriate approach to explain the behavior of those actors who harm others, and even themselves, because they are unskilled. When communication skill is used to purposely harm, communication competence explanations fall short definitionally.

What we do know is that the explanations for both aggression and competence are at the interaction and the system levels. While individual skills are important, the key to understanding argument, verbal aggression, physical aggression and the relative communication competencies associated with them lie at the relational, family, or other group-level systems level. Future research and theory should endeavor to focus on patterns that predict relational aggression and violence, patterns of interaction that ensue, and patterns of outcomes that indicate competence. Consequently, intervention programs should focus on both individual skills and relational patterns, with an eye to educating perpetrators and victims of relational aggression and violence about the ways in which their individual behaviors en-mesh with their relational patterns in the context of cultural frames.