3. Misinterpretations: How Messages Cause Confusion

My brother, Jess, is an enthusiastic cross-country skier. I’m addicted to downhill skiing. A few years ago, when he said he had become proficient on hills and wanted to go downhill skiing with me, I was delighted. As we got off the chair lift, he looked down the slope and exclaimed, “It’s so steep!” Steep? This easy slope? That’s when I realized that the word “hill” meant something different to him than it did to me.

That was my first experience with cross-country confusion. My second occurred just before a first meeting with staff of an East Coast software company. I had begun chatting with people as we assembled for our morning meeting, and one woman told me she had just arrived from the West Coast. Living in Massachusetts, I have suffered through many snooze-less, red-eye flights from the West Coast, and I was sympathetic. “How long did it take you to get here?” I asked. “Three hours,” she responded. Only three hours? I wrote off her response as foggy thinking caused by travel fatigue. Partway through the meeting, I realized, with a jolt, that she was right. Not only were we on the East Coast of the United States, but we were on the east coast of Florida as well, a state with a west coast and one of the company’s other offices a mere three-hour drive away!

Although the previous chapter described miscommunications created by the senders of messages, my cross-country confusion was a result of both the sender’s and receiver’s terminology. In this chapter, I focus on ways both the sender and the recipient may mislead and get misled by each other, despite seemingly familiar terminology.

Two People Separated by a Common Language

When people converse in a common language, they assume that they’re speaking the same language. Yet that assumption regularly proves false. While language helps to clarify understanding, it can also cause confusion, conflict, and unintended consequences when people attribute different meanings to the words they use.1 We each speak in our own idiom, often oblivious to the possibility that our words might have a different meaning to others. And we interpret the messages sent our way without realizing they might have a different meaning to the sender than to us. As both sender and recipient, we’re susceptible to misinterpretations, and in both capacities, the responsibility is ours to question, follow-up, clarify, and do whatever is necessary to ensure that we’re in sync.

1 This is when we are at least nominally speaking the same language. Imagine the situation described in a May 1991 article by Jared Diamond in Discover magazine, about a region of New Guinea the size of Connecticut that has about twenty-five languages, each spoken by a hundred to a thousand people. One such language uses only six consonants and mostly one-syllable words. However, as a tonal language, its four pitches, three possible variations in pitch within a syllable, and different forms of each vowel result in more than twenty permutations. Thus, depending on the way it’s spoken, be could mean mother-in-law, snake, fire, fish, trap, flower, or a type of grub. Diamond reports that his attempts to accurately repeat even simple names were a source of great amusement to the locals.

Let’s be clear: I’m not talking about doublespeak, which, as described by William Lutz, is language that merely pretends to communicate and whose purpose is to “mislead, distort, deceive, inflate, circumvent, obfuscate.”2 No, what I’m referring to here are innocent, unintended differences in interpretations.

2 William Lutz, The New Doublespeak: Why No One Knows What Anyone’s Saying Anymore (New York: HarperCollins, 1996), p. 4.

Cultural differences account for many of these misinterpretations. In Fundamentals of Human Communication, authors DeFleur, Kearney, and Plax describe four cultural factors that affect how we relate to one another:3

3 Melvin L. DeFleur, Patricia Kearney, and Timothy G. Plax, Fundamentals of Human Communication, 2nd ed. (Mountain View, Calif.: Mayfield Publishing, 1993), pp. 153–58.

1. Individualism versus collectivism: This difference concerns whether people place value on emotionally independent, social, organizational, or institutional affiliations (individualism) or on close-knit, supportive, family-like affiliations in which collaboration, loyalty, and respect are prized (collectivism).

2. High versus low context: High-context cultures are ones in which information is communicated in a comparatively indirect and subtle manner, with reliance on nonverbal cues. Low-context cultures are those in which information must be communicated explicitly, precisely, and accurately. An absence of adequate facts, details, and examples in a low-context culture may muddle the message being communicated.

3. High versus low power-distance: This characteristic concerns how people within a culture distribute power, rank, and status—whether equally to all members or according to birth order, occupation, and class or status—and how this influences the way people communicate with each other.

4. Masculinity versus femininity: This factor pertains to whether the culture tends to be traditionally masculine—emphasizing success, ambition, and competitiveness—or traditionally feminine—emphasizing compassion, a nurturing stance, and class or social support.

Adding to these complexities of culture are differing interpretations between people from two countries in which people speak ostensibly the same language. But even being alert to the probability of differences doesn’t necessarily prevent confusion. That’s been my experience each time I’ve presented a seminar in London.

Despite the fact that I know many of the differences between British and American English, time after time, I leave my hotel room, get in the elevator (I mean the lift!), and press “1.” When the door opens, I peer out and wonder, “Where’s the lobby?” having again forgotten that in Europe the ground floor is the one at street level and the first floor is one floor up—what we in the United States call the second floor. This difference isn’t so hard to remember; yet habit compels me to press the button labeled “1” instead of the one labeled “G.”

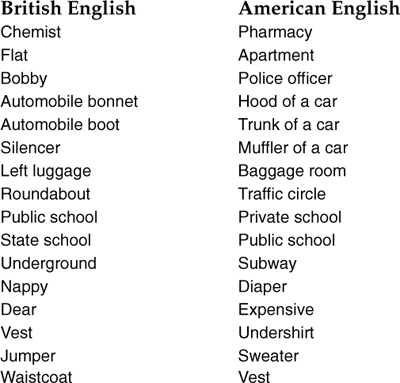

When I describe this experience to my British students, we invariably begin a discussion of the many differences. I recite some of the words that I know have different meanings in their English and mine. They delight in offering their own examples. Amused by the thought that an English-to-English dictionary might help me in my overseas travels, I created one. Here are some of my favorite entries.

Given these differences, as well as the hundreds of others, I now open my London classes by telling students, “If I say anything during this class that doesn’t make sense to you or seems inappropriate or offensive, please understand that this was not my intention. Most likely, I was speaking my English and not yours.” I’ve come to believe that this might be a useful disclaimer for all communication.

Terminology Disconnects

When we talk with people from other English-speaking countries, we often joke about how we come from two countries separated by a common language. But differences in meaning exist not only between countries but also between regions within a single country. Language differences can also exist between professions, organizations, or even subsets of an organization.

Lutz writes in The New Doublespeak that “the 500 most frequently used words in the English language have more than 14,000 meanings.”4 Pick any common word and look it up in your dictionary; you may see as many as twenty, thirty, or even more definitions. The reality is this:

4 Lutz, op. cit., p. 38.

Any two of us are two people separated by a common language.

And failure to identify and clarify differences in interpretation can have damaging effects upon projects, productivity, and relationships.

In theory, the way to avoid misinterpretation and misunderstanding would be for any two, say, English-speaking people to have their own specialized English-to-English dictionary. The same is true for people communicating in other languages. And, as some companies have discovered, a dictionary or on-line glossary is particularly helpful in interpreting acronyms and EMAs (easily misinterpreted acronyms, that is).

With 26 letters in the English alphabet, there are thousands of possible acronyms, so you wouldn’t think we would use the same ones to mean different things. Nevertheless, select any acronym used in your company and you can probably find it being used elsewhere, and even within your own company, to signify an entirely different entity. And, in the world at large, EMAs abound. As a longtime member of the National Speakers Association (NSA), I often forget that, to many people, NSA refers to the National Security Agency.

For decades, technology professionals have been reminded to be judicious in using technical terminology with customers. Business personnel want those serving their needs to know their language (“business-speak,” in other words) and to use it in presenting their explanations, justifications, and rationales. I vividly remember one customer who complained to me that members of the technical staff persisted in talking “network nonsense.” “I don’t know what they’re talking about,” she explained. “I work in a world of loans, appraisals, and mortgage applications; not cycle times, servers, and mips and blips.”

Before the days of personal computing, computer techies took great delight in using technical jargon with customers every chance they got. That was the culture of the time. Using jargon when it was quite clear that others didn’t understand it was a way to exert power, intimidate, and display expertise. It emphasized that it was “them versus us.” Perhaps it was even doublespeak.

These days, technical professionals of all kinds are more aware of the importance of not baffling customers with jargon. However, there are still plenty of exceptions. In my book Managing Expectations, I related the story of the doctor who, before examining me, reviewed my medical records and declared me “unremarkable”! Just short of slugging him (verbally, at least), I realized that he was using medical terminology that meant that I was in excellent condition.5

5 Naomi Karten, Managing Expectations: Working with People Who Want More, Better, Faster, Sooner, NOW! (New York: Dorset House Publishing, 1994), pp. 23–24.

In retrospect, this was a funny experience. Nevertheless, the doctor should have known that the word “unremarkable” has a different meaning in medical jargon than in everyday English. Yet our own jargon is so familiar to us that we often don’t even realize it’s jargon. To us, it is everyday English.

And that is the real lesson here: Be aware of using everyday terms that mean different things to different people. Merely having an English-to-English dictionary won’t prevent misunderstandings because differing interpretations are often about much more than different definitions, as the following sections illustrate.

Project Terminology

In a company I visited, two recently merged software engineering groups discovered that they’d been using the same terminology to describe different things and different terminology to mean the same things. One of their first tasks was to create a shared language so they could understand each other.

Precise terminology is an essential ingredient in the difficult process of defining customer specifications. Take, for example, the matter of what to call a product. As David Hay notes in Data Model Patterns, “In many industries, this is not a problem. A bicycle is called a bicycle by nearly everyone. In other industries, however, different customers may call the same product by different names, and all of these may be different from the name used by the manufacturer.”6

6 David C. Hay, Data Model Patterns: Conventions of Thought (New York: Dorset House Publishing, 1996), p. 103.

It’s easy to assume that two parties using the same terminology mean the same thing. When Pete, a project manager at Quality Coding Corp., undertook a software project for his client Carl, Carl asked for a weekly, written status report. So Pete delivered a status report every Friday. The project concluded on time, within budget, and to specification—successful by all conventional measures. Only by reviewing his company’s post-project client-satisfaction survey did Pete learn that Carl was dissatisfied with the project. Among Carl’s complaints: He never knew the project’s current status.

Pete and Carl had different ideas about the type of information that should be contained in a status report, yet they neither discussed the topic nor took steps to uncover disparities. Because Pete had prepared status reports for many projects, he had no reason to suspect that Carl wanted something different. Seeking clarification never occurred to him.

Carl, however, did have something specific in mind when he requested the status reports, expecting information that would help him communicate project progress to his own management. Had Pete asked how Carl would use the reports or who else might want to view them, or had Carl voiced his dissatisfaction early in the project, the outcome should have been vastly different.

The fact is, it didn’t have to happen that way. Pete should have assumed right from the start, that although he and his client were using the same words, they were speaking a different language. What Pete gave Carl each week was not the status report Carl expected, but what, in Carl’s view, was a jumble of lines, arrows, and bizarre little symbols. Assuming that you and another person are speaking the same words but a different language rarely proves to be a false assumption. Pete was unaware of the important process of communicating about how you’re going to communicate: spending time throughout a project discussing not just the deliverable, but also how the two parties will communicate while that deliverable is being created. You don’t have to make the same mistake.

Meeting Terminology

Stan, a consultant, learned a similar lesson—although, fortunately, before any real damage was done. Two weeks before presenting a class to a group of software project managers, Stan received an e-mail message from his client Sue, requesting an agenda for the class. Stan was surprised. In the preceding months, he’d had several conversations with Sue about the objectives of the training as well as about how he would customize the class to address those objectives. Plus, he’d already given her an outline.

Everything had seemed to be in order. Now, Sue wanted an agenda. Why, Stan wondered, does she suddenly distrust me after so many fruitful conversations? Does she think I can’t do the job? Has she for some reason become unsure that I can do what I promised? Stan’s insides began to talk to him: “What a nuisance! I don’t need this aggravation!” he thought. “Maybe I should back out and save us both a lot of wear and tear!”

But Stan needed the work. He delivered the agenda.

When he arrived at the client site, Sue greeted him and seemed glad to see him, but she also seemed nervous. What Sue said next put her request into perspective for him. Sue had recently been put in charge of training. Three weeks earlier, she had arranged a class for the same software group, the first class she had organized in her new role. Unfortunately, after a strong start, the instructor had gone off on a subject-matter tangent from which he never returned. The project managers were angry at having their time wasted, and Sue couldn’t risk a recurrence. An agenda, which she hadn’t requested for the previous class, would help her monitor the class as it proceeded, enabling her to take action if Stan went off track.

Now Stan understood. Sue’s request for an agenda wasn’t due to a negative reaction to him, but rather, to a negative experience with his predecessor that made her understandably nervous. Stan realized that what Sue wanted wasn’t an agenda per se, but rather the assurance that the class would be conducted as promised. Thus enlightened, he offered to meet with her during breaks each day to review the progress of the class and to see whether she had any concerns.

Stan had fallen into an interpretation trap. Had he asked for clarification of Sue’s request for an agenda rather than try to interpret it, she might have revealed her unsettling past experience much sooner, and he could have both met her need and spared himself distress.

Service Terminology

Not surprisingly, people interpret words in ways that fit in with their particular perspective. For example, when a tech-support group created a service standard stating that it would respond to reported problems within one business day, customers took “respond” to mean “resolve,” expecting that within one business day, they’d receive an explanation of the problem and a solution. But what tech-support personnel meant by “respond” was “acknowledge.” Within one business day, they’d let customers know when they anticipated they’d be able to address the problem.

Now, you might consider this use of “respond” to be so obviously ambiguous that support staff would clarify their meaning before issuing their service standard. But in reviewing the service standards of many organizations, I’ve frequently encountered instances of the word “respond” used without clarification. The people who create the standards rarely do so with the intent to deceive; they are simply oblivious to the potential ambiguity. The notion of ambiguous terminology has never occurred to them.

In addition to “respond,” a considerable portion of other service terminology is ambiguous. For example, what does “resolve” mean? Well, it depends. A hardware vendor publicized the company’s commitment to resolve customers’ problems within four hours. Some customers interpreted this to mean four hours from the time the problem appeared. In fact, what the vendor meant was four hours from the time the problem was reported to the customer-service contact at the company.

I asked the vendor contact when most customers learned of this difference in interpretation. “Oh, the first time they call for help,” he explained. Although customer misunderstanding was common, the vendor did nothing to clarify what was meant. A motivated ambiguity, I suspect, giving customers a good reason early on to take responsibility for obtaining clarification of all terminology pertaining to the vendor’s hardware.

But simply clarifying the time frame for resolving a problem is insufficient if the parties haven’t agreed to the meaning of “problem resolution.” What determines that a problem has been resolved? Must the resolution be a permanent fix? Do workarounds count? What about temporary patches that’ll keep the problem in check until the next release can eliminate it? Furthermore, who determines that the problem has been fixed? The vendor? The customer? Both? Who authorizes closing out the problem? The vendor? The customer? Both? Almost every word of such service commitments bears examination for potential differences in interpretation.

Clearly, these differences are not about mere dictionary definitions, but about how two parties interact. Before they reach closure on what they’ve agreed to, they should compare their understanding of the terminology they’re using. Otherwise, surprises are likely, sooner if not later. Or both sooner and later.

Differing interpretations can occur with other service terminology as well. Take up-time, for example. When a vendor commits to 99 percent server up-time, does this mean 99 percent of the entire tracking period? Or does it exclude specified time periods, such as planned downtime for maintenance and customer-triggered outages? In addition, over what period of time is the calculation of 99 percent being made? Whether an eight-hour outage falls short of the commitment depends on whether service delivery is being tracked over a month or a millennium. Similarly, customers may view a 1 percent outage differently depending on whether it’s a single outage totaling 1 percent of a given month’s service or a month of random two-minute outages that total 1 percent.

These differing interpretations often surface only after customers discover, usually at an inconvenient time, that the standard didn’t mean what they’d originally thought. By then, the damage is done: The customer is unhappy and the vendor has to scramble to resolve the problem—or the two parties enter onto the battlefield of “But I meant . . .” It is much more effective for the two parties to explicitly discuss differences in interpretation to ensure a common understanding of the terminology and its implications for service delivery.

Many organizations use a formal type of agreement called a service level agreement (SLA), which tackles these differences directly. One feature of the SLA is a glossary in which are listed agreed-upon definitions of terms that the parties have discussed and agreed to before service delivery begins. SLAs are an excellent mechanism for helping two parties communicate more effectively and achieve a shared understanding of what they’ve agreed to. The process of proactively discussing terminology is one of the things that makes an SLA so effective as a communication tool and as a way to avoid the misinterpretations that otherwise lead to conflict. The glossary serves, in effect, as an English-to-English dictionary between a provider and customer. (See Chapter 11 for a detailed look at SLAs.)

Business Terminology

Even terms as obvious as “customer” lend themselves to different interpretations. Is it possible for company personnel to not know how many customers the company has? Definitely. In one company, four departments disagreed about how many customers the company had because they defined customers differently and therefore counted them differently.

• One department counted the total number of customers in the database, regardless of their purchasing history.

• A second counted only those that had placed an order in the previous twelve months.

• A third excluded as customers those that had requested information but had never placed an order.

• The fourth excluded those whose payments had been deemed uncollectible.

Each of these definitions was appropriate to the particular business unit served, but oh, the problems that arose when they needed to make joint decisions or interact on behalf of those very customers. Meetings would become forums for debate over whose count was the True Count. And woe to those who requested customer information from any of these departments without first asking “How do you define customer?”7

7 In a private conversation, Jerry Weinberg explained that he’s found the general semantics technique of subscripting very helpful in these cases. Instead of arguing about the “true count” or “true definition” of customers, he tells them that there is perhaps a customer-sub-a and a customer-sub-b—using letters instead of numbers as subscripts, so as not to make a priority of one over the other. Alternatively, they can use the initial of the department name for the subscript, such as a for accounting, r for receivables, and s for sales, because it gives them a mnemonic device and some ownership of the definitions. He points out that helping the pertinent parties make as many definitions of “customer” as needed really cuts down on arguments.

In another company, three groups had conflicting definitions of “customer complaints.”

• One group categorized a complaint as any customer who reported a problem.

• A second group evaluated the customer’s tone in presenting the problem, classifying the tone as either a complaint or a request; the service rep taking the call made a subjective determination.

• The third counted as complaints those matters that could not be resolved within 24 hours.

Is it any wonder that the reports of these three groups appeared out of sync?

Of course, in situations like these, the definitions are often designed to make the group reporting the statistics look good to some judging authority. (“Complaints? Hardly any; just look at the numbers.”) Such conflicting definitions suggest that if you are providing services to a company that based its business decisions on such “obvious” measures as number of customers or number of complaints, you’d be wise to find out how the company defined these terms.

And before you propose a partnership relationship with another party, keep in mind that people have different interpretations of the term “partnership.” Some consider a partnership to be the ultimate professional relationship, with both parties sharing in the risks and rewards, and each party having a stake in the success of the other. For others, partnership means “Let’s you and I agree to do things my way.” I know of two business partners who, while writing a book on building a professional partnership, dissolved their own partnership because they were unable to make it work. Ask them publicly about partnerships and they talk a great line, but ask them privately, and you hear a very different story.

Everyday Terminology

The biggest culprit causing misunderstanding is everyday language. Some words are so much a part of our everyday vernacular that it never occurs to us that other people might define them differently. But often they do—sometimes with serious consequences. Misunderstandings and misinterpretation happen even with the use of simple, familiar words, such as “year.” An amazed colleague once described to me the confusion that occurred when she insisted that she could complete her customer’s requested analysis “this year”—after all, it was only February. The customer strenuously disagreed.

If you’re thinking that one party to the conversation meant calendar year and the other meant fiscal year, you’re so near and yet so far. My colleague did mean “this fiscal year,” which ended in September. The customer, she finally discovered, meant “this fish-sampling year,” which ended in May! The customer was a scientist, whose prime data collection was done between March and May. In his business, the year ended in May.

The challenge is to find these differences in terminology before it’s too late. My colleague now recommends having an “interpreter” on a project team to translate between the scientist and the software engineer. That’s not a bad idea between any two parties, as the following examples illustrate.

Involvement

A mega-corporation’s network-management department (NMD) undertook the upgrade of networking technology used by its internal customers, many of whom were remote from corporate headquarters. These internal customers had experienced a long stretch of poor service and asked to be involved in the upgrade. To accommodate this request, and in hopes of reversing customer dissatisfaction, NMD staff periodically updated customers by phone, offered to visit them on-site, and requested their feedback in response to written reports. Yet when I interviewed the customers, they explained with frustration that NMD was ignoring their desire to be involved. Clearly, there was a communication gap between the two groups, but what was causing it?

I asked several customers what they meant by “being involved.” One said he wanted to be invited to meetings at which key issues were being discussed. Another wanted to be able to ask for the reasons behind key decisions, and to get a clear and complete answer. A third wanted to be interviewed because (she said) her department had unique needs. The fourth said he’d be satisfied if NMD would just return his phone calls! Clearly, what these internal customers meant by “being involved” differed significantly from what NMD thought they meant. Perhaps NMD could have accommodated these differing wishes or perhaps not. But lacking awareness of these differences, NMD’s attempts to be responsive were adding to customer dissatisfaction, not reversing it.

NMD at least deserved credit for trying, unlike one IT organization that conducted a strategic review of its policies and practices, and named its undertaking The Voice of the Customer—but didn’t involve customers at all. This organization didn’t need to worry about conflicting interpretations of “involve” because the very notion of involvement had not entered the thought process. The only voice the organization’s management wanted to hear from its customers was the silent voice of total compliance.

Difficulty

At a conference I attended, Dale Emery, a specialist in transforming people’s resistance to change, described the reasons people commonly cite when resisting a change to a new technology, a new methodology, or a new procedure. One common reaction is, “It’s too difficult.”8 It’s possible that the person quite literally means that adopting the new way is too difficult. However, what is usually meant is something else, such as, “I need to be able to set aside time to learn it.” Or, “I need help in understanding it.” Or, “If some adjustment could be made so that I have some time to tackle it, I could do so.”

8 Dale Emery, “A Force for Change—Using Resistance Positively,” Software Quality Engineering Software Management Conference, San Diego, Feb. 14, 2001. See also www.dhemery.com.

The same reasoning applies to other reactions to change, such as, “It’s not worth using.” Or, “I have no time.” Taking people’s words at face value during times of change can lead you to the wrong conclusion. Emery cautions that it’s important to consider alternate interpretations of people’s reasons for not embracing change; often, people mean something other than what they’re saying. Your challenge is to inquire and learn more.

Communication

People frequently complain about insufficient or inadequate communication, yet the very word “communication” is subject to multiple interpretations. For example, one director I worked with conducted a survey to determine the cause of low morale among employees. One of his findings was that the employees desired more communication. Eager to put things right, he circulated a greater number of reports and memos than ever before, as well as numerous articles from periodicals. Morale, however, did not rise.

Why? Because when the employees said that they wanted “more communication,” what they really wanted was increased attention and recognition. They wanted the director to wander by their desks more often to ask how things were going. They wanted to feel that he appreciated how hard they were working. They wanted to hear from him not just when they made mistakes, but also when they did things well. Yet, savvy though he was, the director never questioned either their interpretation of “more communication” or his own, so he couldn’t understand why his good intentions changed nothing.

Both those who contribute to misinterpretations and those who fall victim to them usually have good intentions. They are doing the best they know how. But both parties to miscommunication too easily forget that although they are using the same words, they speak different languages.

The Sounds of Silence

Even silence can be ambiguous, especially if you’re interacting or negotiating with people from another country or culture, or from another organization or social milieu. I remember reading a newspaper clipping that described a key point during the negotiation between two U.S.-based companies. As final settlement terms were put on the table, one party remained silent, intending to convey its dissent. Using silence to mean dissent was part of the cultural norm in that company, and its negotiating team took its meaning for granted.

The second company took the silence to mean agreement, believing that if members of the opposing party disagreed, surely they would voice their dissent. Tracing the subsequent disputes between the two companies to this difference in interpretation took some doing, and resolving the resulting mess took even more. Clearly, silence indeed can mean different things to different parties.

Fleeing Felines

Fortunately, not every misinterpretation is serious. Some of the most amusing ones occur when we hear something, interpret what we heard, draw a conclusion, and act—because the situation is so clear-cut that we have no reason to doubt our interpretation. One of my favorite examples of this kind of cause-effect interpretation is The Case of the Great Cat Escape. I was presenting a seminar at a client site when a secretary came and told Tara, a manager in the group, that her neighbor had called to report that Tara’s cat, Panther, was running around in the hallway outside her apartment.

“Not again!” Tara exclaimed. She said the cat probably dashed out when her cleaning lady opened the door to her apartment. Fortunately, Tara lived only a few blocks away. Her secretary offered to go to Tara’s building, retrieve the cat, and return him to Tara’s apartment. Which she did—and didn’t. That is, she did go to Tara’s building. But she didn’t retrieve the cat and return it. Why? It seems the cat wasn’t Tara’s. She’d met Panther before, and she knew this wasn’t him.

Tara quite reasonably had assumed it was her cat. After all, Panther had gotten out of the apartment before, so she had no reason to question the situation. As a result, she didn’t think to ask whether her neighbor had described what the cat looked like, or where, exactly, it was found, or if it responded to “Panther.” The likelihood was that it was her cat—except it wasn’t.

The fact that Tara lived nearby eliminated the need to analyze her interpretation of the situation. She lived only a few blocks away, and her secretary could just dash over to her building. If the cat had been hers, the problem would have been quickly resolved. But what if Tara had lived further away? What if her secretary hadn’t been so accommodating? What if the temperature had been 30 degrees below zero or raining you-know-whats and dogs?

Misinterpretations are especially likely to occur during times of stress, and when they do, they may have less amusing consequences than in Tara’s case. Taking a moment to challenge one’s interpretation is rarely a waste of time.

Clarify, Clarify, Clarify

The preceding examples illustrate how easily circumstances as well as terminology can be misinterpreted. Strongly felt ideas about policies, processes, attitudes, and intentions influence the way people perceive each other and interact with each other. The words they choose frequently mean different things to each of the parties to an interaction. To assume that parties share the same interpretation and then to act on that assumption can have serious consequences. As the family therapist Virginia Satir observed, “. . . people so often get into tangles with each other simply because A was using a word in one way, and B received the word as if it meant something entirely different.”9

9 Virginia Satir, Conjoint Family Therapy (Palo Alto, Calif.: Science and Behavior Books, 1983), p. 81.

Author and IT management consultant Wayne Strider notes that when someone disagrees with him, it’s easier for him to handle the situation when he knows that his message has been understood. He points out that unless he is certain that his message has been understood, he has no way of knowing whether the person disagrees with his intended message or with some misunderstood variation of it.10 The same, of course, applies when someone agrees with you: It is important to know that the person agreed with what you meant, rather than with some misinterpretation.

10 Wayne Strider, private communication. Wayne is author of Powerful Project Leadership (Vienna, Va.: Management Concepts, 2002). For additional information, see www.striderandcline.com.

The way to prevent misunderstandings is simple in theory although tedious: Follow every word you write, sign, or speak with a clarification of what you mean, and follow every word you read, see, or hear with a request for clarification. To be absolutely sure that you are communicating exactly what you mean, you could diagram each sentence, the way my elementary-school teachers did when teaching me English grammar. To me, a diagrammed sentence was a hodgepodge of lines drawn at various angles, with each word snatched from its rightful place in the sentence and affixed to one of these lines. I could never understand why anyone would want to rip apart a perfectly good sentence in this way. But if it would improve communication . . .

Clarify Interpretations

If these approaches seem cumbersome, then try this: Make a commitment to become sensitive to the potential for differing interpretations. When customers, teammates, or others give you information, ask yourself this question:

Am I sure I understand what they mean?

If your answer is no, make it your responsibility to ask clarifying questions. Be as specific as possible, and ask for examples. Questions that might have helped to prevent some of the misinterpretations described in this chapter include the following:

Status report:

• What kinds of information would you find helpful in a status report?

• How will you be using the report?

Agenda:

• I’m curious about why you’re asking for an agenda after we seemed to have everything in order. Can you say more about that?

• Since I’ve provided you with an outline, what additional types of information would be helpful to you?

Resolve:

• How do you decide that a problem has been resolved?

• What kinds of criteria can we establish so that we both agree that a problem has been resolved?

• When you say you’d like us to involve you in this effort, I take that to mean you’d like us to call you periodically and request your feedback. How close is that to what you were thinking?

• What kinds of things do you have in mind when you say you’d like to be involved in this effort?

Communicate:

• What are some things that would help you feel we’re doing a better job of communicating?

• What kinds of changes might help us eliminate the current dissatisfaction regarding communication?

In formulating questions, don’t fall into the same trap as a director I talked with recently who requested customer feedback on material his group had prepared, and asked customers: Is the information clear and unambiguous? Think about that question. If you review material and find it confusing, you know you found it confusing. But if you find it clear and unambiguous, it may be that you misinterpreted it, but were clear that your (mis)interpretation was correct—which proves that it’s ambiguous.

The risk of posing questions that can be answered yes or no is that the response provides little indication of the real situation. Notice that all of the clarifying questions listed earlier in this section require some explanation or elaboration. The additional information generated and shared through the ensuing discussion will reduce the likelihood of misinterpretation.

Whenever you are certain that you fully and completely understand the other party without benefit of clarifying questions, ask yourself this question:

If I weren’t absolutely, positively certain that

I fully and completely understand, what would I

ask?

Keep in mind that it’s in situations of absolute certainty—situations in which you’re sure you understand—that you’re most likely to misinterpret. Make it your responsibility to clarify your own terminology to ensure that the other party understands you. As you provide clarification, use these questions as a guide:

1. What assumptions might I be making about their meaning?

2. What assumptions might they be making about my meaning?

3. How confident am I that I’ve exposed the most damaging misinterpretations?

The best policy is simply to try to heighten your awareness of the potential for misinterpretation. You probably can’t catch all communication problems, but if you do the best you can, and don’t allow yourself to feel too rushed or too intimidated to ask for clarification, you should find that you’re in sync with the other party. If you’re not, it’s better to find out early on, rather than later when the consequences could be catastrophic.

Clarify Agreements

For informal commitments, these clarifying questions probably will suffice. But for more formal commitments, such as when you’re developing products or designing services, it is important to put the details of the agreement in writing. Then go through the written document, discussing each important word or phrase, ensuring that you and the other party agree about its meaning. Consider creating a glossary of key terms to prevent misinterpretation by others who may later have responsibility for carrying out the agreement, but who were not involved in its creation.

In addition, communicate your expectations early and often. Never assume that you and the other party have the same understanding of what you’ve discussed. Ask questions. Check, and then double-check. State your understanding and ask if you’ve got it right. Be guided by a variation on two questions I previously mentioned:

1. Am I sure I understand what we agreed to?

2. If I were unsure, what would I ask?

Whenever the outcome of a discussion is that one or both parties have agreed to take some action, conclude with a restatement of what you’ve each agreed to do. Make sure both you and the other party understand your own and each other’s responsibilities. Allocate time for this clarification process, so that if you discover conflicting interpretations, you can resolve them without feeling rushed. And if you do identify some differences, give yourself a pat on the back, because you caught a miscommunication early on that could have had serious ramifications if left undetected.

Set the stage for the clarification process by explaining its purpose. Point out the prevalence of ambiguity and comment on how easily misunderstandings occur. Offer real-life examples that will hit home and discuss how both parties can work together to minimize confusion and maximize understanding. Make a commitment to discuss disparities sooner rather than later.

By taking these steps and the others described in this chapter, you’ll reduce the likelihood that misinterpretations will happen. In the process, you’ll be improving your communication skills dramatically.