CHAPTER 3

Listening Skills

We have two ears and only one tongue in order that we may hear more and speak less.

—Diogenes Laertius

Chapter Objectives

This chapter introduces the mother of all communication–listening. While emphasizing the primacy of listening among all the skills, it distinguishes between hearing and listening. It further discusses the processes of active listening and other kinds of listening. Barriers to listening and good listening are elaborated alongside activities like Chinese whisper etc.

THE LYNCHPIN OF COMMUNICATION

Listening can be described as a skill that involves receiving, interpreting and responding to the message sent by the communicator. Like any other skill, listening skill also needs to be learnt and developed for effective communication. It is, in fact, one of the most important skills that play a vital role in the process of communication. As listening can be seen as fundamental to all communication, poor listening can become a major barrier to communication. It can result in break-down of communication, or wrong, improper and incomplete communication. Messages can be lost, misunderstandings may crop up, and people may perceive or be perceived wrongly.

HEARING AND LISTENING

Most of the problems discussed above crop up because we do not discern between the two activities, listening and hearing. Hearing is primarily a physical act that depends on the ears. Unless there is a physical disability or problems such as noise or distance, it happens automatically. It requires no special effort from the listener. ‘Listening’, on the other hand, is a much more conscious activity that demands a lot more than just hearing. It requires the conscious involvement of the listener, the acknowledgement of understanding and response. The listener has to hear, analyze, judge, and conclude. When a person is listening, he is constructing a parallel message based on the sound clues and verifying whether his message corresponds with what he hears. Hence, listening is an active process in which the listener plays an active part in constructing the overall message that is eventually exchanged between a listener and a speaker. It is a process that actively engages the speaker as well as the listener. Both are equally involved. Even as the listener is listening, he has to process the facts, study the body language of the speaker and also project the appropriate body language to the speaker. The speaker, in turn, has to cognize the feedback given by the listener and respond. It is, in other words, like a sea-saw, where both the listener and the speaker monitor one another's response and then act. A person, who listens well and engineers his body language appropriately, is seen as a ‘good conversationalist’ even though he actually speaks less. This is active listening.

One of the most valuable things we can do to heal one another is listen to each other's stories.

—Rebecca Falls

ACTIVE LISTENING

Most of the problems in ‘listening’ arise because of the discrepancy in our speed of talking and listening. On an average, we can speak around 120 to 150 words a minute. But the brain is capable of processing 500 to 750 words a minute. Most of the brain is idle when we are just listening. Attention, thus, gets dissipated and the mind starts getting engaged in other things. As a result, our listening becomes partial and selective. Often instead of listening and trying to understand what the other person is saying, we get more involved in forming our counter arguments. This also becomes a kind of selective listening where, more than listening, we are involved in our own response. In effective and active listening, the listener, after grasping the content of the speaker gets engaged in trying to understand him. He looks at the problem from the other person's perspective, engineers his body language appropriately giving the listener constant feedback. This process, as mentioned earlier, is as engaging as talking. Thus, it leaves no space in the listener's mind empty for speculation or formation of anti-discourse.

ACTIVITIES

- In a group, find out one person who loves cricket and another who does not. Make them sit facing one another and give the following instructions.

For a couple of minutes, think about the reasons why you like or dislike cricket. Start giving your views simultaneously. Rather than listening to your opponent's viewpoint, try to impress your views on him. Continue doing this for about 10 minutes.

When the task is complete, take a feedback of what went on from the two participants Take the opinion of the audience too.

- Make a slight variation of the same exercise. Instead of ignoring the other viewpoint, each participant should carefully listen to what the other is saying, paraphrase it, and then put forth his own point. The conversation of each, thus, should begin with this pattern:

So you feel that __________.

but I feel differently. I believe that __________.

At the end of the exercise the audience should note the difference in the body language of the listeners in the two exercises. The differences can be analyzed along the following parameters.

Task for the two participants : Enact the situations. At the end of the performance each of you should note down your feelings about the other. Now read one another's role-description and re-enact the situation. Is there any difference in the way you feel for one another now?

Task for the audience : After watching both the performances, analyze the kind of listening the teacher did in the first performance. Did it become different the second time? Give reasons for the change if there had been any.

Take more topics like classical music, network-marketing or job-hopping, select people with strong opinions for and against the topic and repeat the exercise. In every case, note the difference in the body language during the two exercises. Make a list of the common differences you found in the body-movements. Anyone from the audience can make a brief presentation on it. Include in the list any commonality in the feelings that the participants reported. Put together, these can be seen as the basic differences between how people react during hearing and listening.

“One of the best ways to persuade others is with your ears—by listening to them.”

—Dean Rusk

KINDS OF LISTENING

The exercises make it evident that there are different kinds of listening. Depending on the quality of listening, it has been divided into four types.

Ignoring: This is the kind of listening where the listener is entirely ignoring the message as well as the message giver. He/she might just be ‘pretending’ to listen while doing or thinking something else. This can be very damaging because the listener's lack of participation becomes evident through the body language. The speaker might feel snubbed and hurt, which might further lead to a total break-down of communication. The same preoccupation might also result in the listener not taking note of the speaker's reaction.

Selective Listening: Selective listening is listening to parts of the conversation while ignoring most of it. This is the kind of listening we practise often while listening to repeated public announcements or the TV news if we are looking for some specific information. If we are waiting for news about the cancellation of trains in a certain route, for example, extensive coverage about a cricket match or weather is most likely to be at the fringe of hearing. We register the broad topic at times but the details are ignored. The brain registers the topics and then dismisses them or just ‘shuts off’. This often happens in classrooms too. Many students practise selective listening. The whole lecture is rarely listened to with the same intensity. Individual students pick up topics of their concern or interest in a lecture and pay close attention to it. The rest of the content is either given peripheral attention or ignored. It is only sometimes that a whole lecture is absorbed similarly.

It is interesting to note the instantaneous change in the body language when the listener moves from the non-listening to the listening phase. The facial expression becomes more focused. The eyes, especially, show a lot more concentration. The listener might even lean forward in the chair or towards the speaker or might straighten up and turn towards the direction the message is coming from. When the message has been observed, the body language relaxes visibly. This can be noticed in the slumping of the shoulders and diminishing eye-contact. During any conversation, it is very important for the speaker, especially, to look out for these signs. If the listener or listeners are listening only selectively, the structuring of the content may need to be altered; the material may have to be made more relevant, or repetitions may have to be avoided. But if you are a listener engaged in a conversation with a speaker, beware. Your body language will most probably give away that you are listening only partially!

Attentive Listening: Attentive listening in a kind of listening where there is no selective dismissal. The listener listens to the speaker completely, attentively, without glossing over or ignoring any part of the speech. This is the kind of listening we find when there is a discussion, for example, on a topic we are interested in or we are critically examining a piece of information for further discussion. Critical listening allows us to form an opinion on the topic being discussed and even design our response appropriately. It allows us to assess the viewpoint, the perspective of the speaker and weigh the arguments appropriately.

Empathetic Listening: This is the ultimate kind of listening that is done not just to listen and understand, but understand the speaker's world as he sees it. Here, one empathizes with the speaker, understands his viewpoint but does not necessarily agree with him. This kind of listening has almost a therapeutic effect on both the speaker and the listener.

Empathetic listening is different from attentive listening or critical listening. As Stephen Covey puts it, here listening gets into “another person's frame of reference. It is listening, not only with one's ears, but one's heart”. To quote Covey again, “you listen for feeling, for meaning. You use both your right brain as well as your left. You sense, you intuit, you feel”.

This is the kind of listening one friend gives to another friend when the latter feels the need to speak, or a sympathetic parent gives to the growing child if he/she has come back from school, troubled.

When you are listening to somebody, completely, attentively, then you are listening not only to the words, but also to the feeling of what is being conveyed, to the whole of it, not part of it.

—Jiddu Krishnamurti

ACTIVITIES

- 3. Look around you and make a note of situations when you and others listen. You'll find them in plenty! Try and categorize them. Note five situations when you think you and others do the following kinds of listening.

- Critical listening

a.

b.

c.

d.

e.

- Selective listening

a.

b.

c.

d.

e.

- Ignoring

a.

b.

c.

d.

e.

- Critical listening

- 4. Make a note of a situation when you thought that you were adequately listened to. Try and recollect how you felt, using three adjectives to describe your feelings. Also try to recollect what it was in the person that made you feel so. Use three adjectives to describe the attributes of the listener.

| Your feelings | The listener's behaviour |

| a. | a. |

| b. | b. |

| c. | c. |

Recollect five points about the body language and the facial expression of the listener.

a.

b.

c.

d.

e.

Role-Play

The Situation: This is a role-play that shows the conversation between a teacher and a fourth-year engineering student. The student was supposed to have submitted his assignment three days ago. But he has been missing. He has come with it now. (With this introduction, give the role descriptions to each separately. Do not let one look into the description of the other. But in the absence of both, the audience should hear both the role descriptions).

The Teacher: You are a strict disciplinarian. You believe that a deadline is a deadline. Students coming up with reasons for delaying work is a source of constant irritation for you. This time you have decided that you'll not accept assignments if there is any delay. This student coming now can do well if he applies himself. You appreciate him. But often, he disappears from college without any information. You are determined to teach him a lesson. You believe that it is for his good that you are doing this.

The Student: You are a good student but you know that you are under-performing. Your father is an alcoholic and sometimes does not come home for days. At such times you have even gone searching for him. You have not shared this problem with anyone. This time you wanted to finish the assignment on time, you also put in your best. But, again, your father disappeared and you had to go in search of him. You have come back with the assignment as soon as you could. You are tired, irritated, and you now dread meeting this teacher who, you feel, unnecessarily makes things difficult.

The people of the world are islands shouting at each other across a sea of misunderstanding.

—George Eliot

BARRIERS TO GOOD LISTENING

Sometime or the other, all of us listen partially, we do selective listening. Some times we also ignore some messages. There are many reasons as to why we do not listen completely. Some of them are the following:

- Physical reasons : One chief cause of bad listening could be a person's inability to hear properly. Apart from this, noise and distance too could become barriers to listening properly or not listening at all. Anyone who has tried talking on a running train or pass on a message to someone across a crowded street has experienced what a physical barrier could be.

- Age and Attitude: Age and attitude are sometimes reasons for not listening well. A four-year-old child's constant conversation is likely to be ignored by most parents. A teenaged son or daughter is similarly likely to ignore the parent's constant caution about driving rules, etc. Difference of age often makes one feel that the person speaking cannot possibly have anything interesting or relevant to say. This, often, creates an attitudinal block, which results in the listener ignoring the message or assimilating it partially.

- Mental Set: Sometimes, the listener is already conditioned to think that the speaker will adopt a particular attitude or a line of argument. If a conversation begins with this kind of mind-set, it is obvious that no ‘listening’ or communication will take place. The listener might entirely ignore what the speaker says or listen to only what he/she thinks the speaker will say. Meanings here will be wrongly inferred and vital parts of the conversation will be skipped.

This kind of a mind-set can be extremely harmful in both professional and personal interaction. If one comes to the negotiation table, for instance, with a closed mind determined to reject the opponent's proposal, there is little chance for the talks to go forward and reach a resolution. In inter-personal situations, similarly, if one is pre-determined to look at a person or his talk in a particular light, there is little chance of our forming a correct opinion about him and his views. Such conditioning often prevents a bad situation from getting better. It makes one blind to the fact that people might be willing to change, or be more accommodative.

- Language: Language can be yet another reason why people do not hear correctly. It could be the problem of a French speaker conversing in English or a Tamilian trying to speak in Hindi. The mother-tongue interference plays a major role and prevents the listener from listening correctly. It is important, therefore, to make sure that we speak the language we are conversing in with reasonable clarity.

While speaking English, especially, it is important to be aware of our pronunciation, tone, pitch, modulation and stress.

Language can sometimes be very context specific. A group of college boys and girls talking in the college canteen, for example, can have an altogether different register. Slang might be used in specific ways and words too might have different codes and meanings. Listening here will mean being familiar with the particular register. Unfamiliarity can become a barrier to listening. In specific knowledge areas and professions certain words have specific meanings. Unless specified, these too can become barriers to listening comprehension. The same is true of in-house acronyms.

- Careless Listening: It is a common sight to see people looking at papers, sifting through lists or even fidgeting with objects like paper weights while listening. This can put the speaker in a very awkward position. He has no clue of what the reaction of the listener is or even whether the listener is listening to him or not. Such actions can be annoying for the speaker. It can also be seen as a way of snubbing or dismissing what the speaker is saying. Often, it can also indicate to the speaker that what he is saying is not important for the listener. This kind of gesture can seriously hamper communication if used by superiors at the workplace or in any interpersonal communication. If the speaker does not feel ‘listened to’, the act of communication will always remain incomplete. Listening in such cases, is bound to be partial. Even if the facts are conveyed, understanding of the facts is generally inadequate or incomplete.

Such habits are commonly observed during telephonic conversations. Since the listener is not present right in front, speakers often tend to do paper work, fidget or draw diagrams. The speaker, in fact, should be more careful during a telephonic conversation. The listener has no inputs from the speaker except the voice, the pitch, the modulation and the pauses. Body language and facial expressions are absent in this form of communication. So the language being used, the pitch and modulation, and especially the pauses have to be used very carefully to convey the right shade of communication or even avoid mis-communicating!

Role-Play

This is a situation where an employee has come back from the boss’ room agitated and angry. The report, which was to be submitted the previous day is not yet ready. The boss blames the employee for the delay but she feels that her share of work was done long back. Back in the common room, she is talking about it to her colleague and friend. This is a conversation between the friends.

Role Descriptions

Friend–1: You are new to the job but you feel that right from the beginning, your boss has been trying to find faults with your work. Even now you feel that he did not hear what you had to tell him about the work distribution. You are angry and you want to complain to the person next in hierarchy.

Friend–2: You are a good friend of this employee. You have worked longer in the organization and you know your boss as a fairly reasonable and balanced person. You feel there has been some mis-understanding somewhere. You also know that your friend is impulsive. You do not want her to take the matter to the next in authority.

After the role-play has been enacted, have a general discussion on the following points.

- The communication barriers that you could observe.

- What caused the barriers?

- How could they have been avoided?

ACTIVITIES

- 5. Given below are certain statements and also the responses. Which do you think is the best possible response?

- An old woman sitting next to you in the train starts complaining about rheumatic pains. “These knees are getting worse. God knows how many more days I'll have to suffer them. Living with such pain is not worth living.”

You reply saying:

- This is common at this age.

- May be, you haven't seen a good doctor?

- It must be really painful!

- An old friend speaks to you about her broken engagement: “I feel betrayed. He just took me for granted. I can't imagine he could be so rude to me. What does he think of himself after all?”

You reply saying:

- Just forget him. There will be many more ready to wait on you.

- You're stupid to have believed him.

- Couldn't you find anyone else.

- Oh dear! You must be shattered!

- A small child walks into the room saying, “The clouds outside are strange! Yesterday I saw an elephant today, it is like a mother and a child. There is a flower also!

You say:

- You are always dreaming.

- Clouds keep moving, my child. The shapes are just formed to change.

- Shall I tell you how clouds are formed?

- It is fantastic! You know, I had once seen the sea and a jumping whale in the cloud.

- You come back home late after a hard day's work and your husband greets you saying: “It was a terrible day for me. My bike had a flat tyre. I forgot my papers at home. The work had to be redone in office. And when I came back, I found that the kid had not eaten in the afternoon. I've been trying to feed her since then. But she refuses to touch food. She's just stubborn and unreasonable”.

You reply saying:

- I've had my share of problems too today.

- This girl needs a real spanking!

- You've been really stressed out today.

- Can't you see I'm just back?

In each of these cases, analyze what each of the answers would mean and decide which would be the best possible response.

CHINESE WHISPER

Choose five volunteers from the class. Ask four of them to be outside. Read the contents given below to the only volunteer present inside and the class. Ask the people outside to come in one by one. The first person should repeat it (whisper it) to the second, the second to the third and so on. Observe the way the message changes. After the fifth person listens to it, ask him to repeat it once to all present. Compare it with what was said first. (This is done to show how message gets lost while traveling; what we listen to and what we ignore; the manner in which we summarize, interpret, and recreate while listening)

“A scooter was coming at great speed from the south end of the factory and trying to move towards the north-west. Even as it was trying to enter the lane to the left, a truck coming from inside the lane blocked its way. The scooterist tried to overtake but was again stopped by a car coming behind the truck. He came very near to dashing the car. The car driver, thoroughly disgusted with the traffic, came out and cursed the scooterist. Upset with all this, the scooterist turned back with great difficulty and took the next lane.”

Wisdom is the reward you get for a lifetime of listening when you'd have preferred to talk.

—Doug Larson.

GOOD LISTENING

A good listener will:

- Try to understand the speaker's perspective. It is not necessary to agree with the speaker, but a good listener will always try to see from the speaker's perspective.

- Listen with the whole body – As we have seen, the listener is as active a participant in the act of conversation as the speaker is. For the speaker, the body language of the listener is one of the most important sources of getting feedback. The sitting posture, the facial expression and eye contact are important clues for the speaker to go on speaking or to stop. They can encourage, discourage or even snub the speaker. If you want the speaker to feel reassured, listen with your whole body, let the speaker know that you are listening and you understand.

- Do not judge prematurely – Since the brain can process speech much faster than one can speak, it is easy to think ahead, judge the talk and even evaluate the speaker and his talk. A good listener, however, will always try to look at the speaker's perspective, try to understand why the speaker feels the way he/she feels. If you want to be a good listener, therefore, avoid judging the speaker's talk or personality prematurely. Give some time. Try to understand and then arrive at a conclusion.

- Go beyond the words of the speaker – As said before, a good listener will always try to understand the speaker's perspective. But more than the words, it is important to understand the spirit, the sentiment that keeps the conversation going. For good listening, thus, it is necessary to not get stuck in the web of words. One has to analyze the context, study the body language, judge the attitude of the speaker and the reasons why one is responding the way he/she is. It is necessary, therefore to go beyond the words of the speaker

- Paraphrase the speaker – A good speaker, while listening, might also paraphrase the speech of the speaker. This may not be a detailed paraphrasing, but responding in a few words. Adding nothing, changing nothing, asking no questions, just summarizing the speaker's thought and giving information about what has been understood.

- 6. Read out the following passage to the class loudly and clearly, and complete the activities given below.

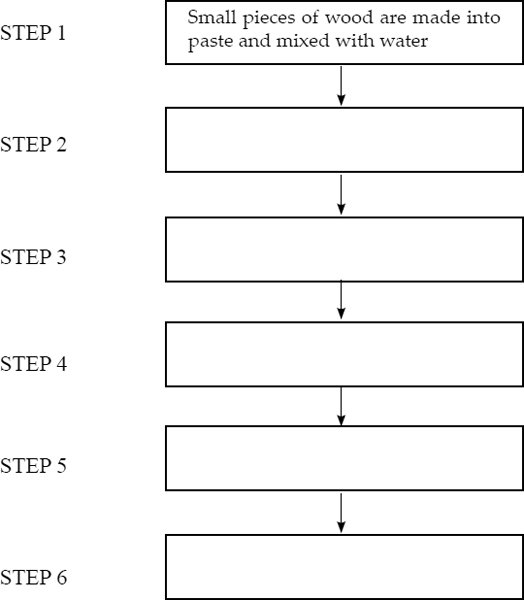

For centuries, the principal raw materials for making paper were cotton and linen fibres obtained from rags. Today, these have been largely replaced by wood pulp. Trees are cut down, taken to the sawmill and chopped up into small pieces. The pieces of wood are then ground up and mixed with water to make wood pulp. The wood pulp is then washed to clean impurities. It may then be bleached to make the paper white. In the next step, starch or clay may be added to improve the surface of the paper. The pulp is then fed into the paper making machine. In this machine, the pulp is spread across large areas of wire mesh-sheets of metal with a large number of holes in them. Here, the water is drained off. The sheet is then passed between rollers, which squeeze the water out. The dry sheet then travels through a series of heated drums. At this stage, a coating may be applied to make the paper smooth and shiny. This process produces a continuous sheet of paper, which is wound into giant rolls. It is then trimmed to remove the rough edges, and cut to the desired width.

- Listen to the description of how paper is made and complete the flow chart.

- State if the statements given below are true:

- Good pulp is bleached to clean out the impurities.

- The paper-making machine has a large wire-mesh on which the pulp is spread.

- The pulp is adjusted, trimmed and cut at this stage to remove rough edges.

- The sheets are passed between rollers to squeeze out excess water.

- The heated drums are primarily used to give a glossy coating to the paper.

- 7. If you listen to the English of any good speaker carefully, you'll realize that only a part of a word or one part of the sentence is stressed at a time. Proper stress is very important in determining the meaning of a sentence. Read the sentences given below, stressing only one word at a time. Every time you read the sentence, stress only one of the words underlined and discuss the different meanings that emerge.

ST-1: Did Sita tell you that she was leaving?

ST-2: It is surprising that you mentioned this fact.

ST-3: Could you please leave me alone?

ST-4: I've never seen you so angry before.

ST-5: Did Saurav buy that black car?

Build dialogues around the different meanings you find in every sentence each time you stress a different word (Maybe, you could divide the work between five groups and enact them in front of the others)

Here is an example:

ST-1: Did Sita tell you that she was leaving?

Stress — Sita

- A

- Hey! I just heard that Sita's visa is through.

- B

- Really? But I always thought she was strongly against people leaving the country.

- A

- All that makes good talk, you see. When the opportunity comes who would like to refuse?

- B

- I still have my doubts about the whole story. Did Sita tell you that she was leaving? (There should be two more dialogues from this sentence, one stressing on “you” and the other on “she”. Take into account the changed meaning every time you change the stress and compose the situational dialogues accordingly.)

SUMMARY

- Hearing is distinct from listening. It is listening alone that makes a communication meaningful.

- Listening to somebody with the whole of your attention says, “you matter to me”.

- We listen much faster than we can speak. ‘Understanding’ will fill the gap in speed.

- In listening, the listener is as much involved as the speaker is.

- Careless listening can snub the speaker and halt the entire communication process.

- To listen well, one does not have to agree with the speaker but try and understand the speaker's perspective.

- Since listening can be seen as fundamental to all communication, poor listening can become a major barrier to communication.

- Listening is a much more conscious activity that demands a lot more than just physical hearing.

- A person who listens well and engineers his body language appropriately is considered a good conversationalist even though he actually speaks less.

- An effective and active listener, after grasping the content of the speaker, gets engaged in trying to understand him and looks at the problem from the other person's perspective and engineers his body language appropriately giving the listener constant feedback.

- Selective listening is listening to parts of the conversation while ignoring most of it.

- Attentive listening involves listening to the speaker completely, attentively, without glossing over or ignoring any part of the speech.

- Empathetic listening is the ultimate kind of listening that is done not just to listen and understand, but understand the speaker's world as he sees it. It is getting into another person's frame of reference.

- Most of the problems in listening arise because of the discrepancy in our speed of talking and listening.

- Physical reasons, age and attitude, mental set, language and quality of listening are some of the other factors that become either barriers to or enablers of good listening.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

- How can we define listening?

- What is the difference between hearing and listening?

- Discuss the concept of active listening.

- What are the four types of listening?

- What is the difference between ignoring and selective listening?

- How do you relate attentive listening to empathetic listening?

- What are the barriers to good listening?

- Discuss the role of attitude in listening?

- What do you understand by careless listening?

- Discuss the role of language in effective listening.