1

The Communication Technology Ecosystem

Communication technologies are the nervous system of contemporary society, transmitting and distributing sensory and control information and interconnecting a myriad of interdependent units. These technologies are critical to commerce, essential to entertainment, and intertwined in our interpersonal relationships. Because these technologies are so vitally important, any change in communication technologies has the potential to impact virtually every area of society.

One of the hallmarks of the industrial revolution was the introduction of new communication technologies as mechanisms of control that played an important role in almost every area of the production and distribution of manufactured goods (Beniger, 1986). These communication technologies have evolved throughout the past two centuries at an increasingly rapid rate. This evolution shows no signs of slowing, so an understanding of this evolution is vital for any individual wishing to attain or retain a position in business, government, or education.

The economic and political challenges faced by the United States and other countries since the beginning of the new millennium clearly illustrate the central role these communication systems play in our society. Just as the prosperity of the 1990s was credited to advances in technology, the economic challenges that followed were linked as well to a major downturn in the technology sector. Today, communication technology is seen by many as a tool for making more efficient use of a wide range of resources including time and energy.

Communication technologies play as critical a part in our private lives as they do in commerce and control in society. Geographic distances are no longer barriers to relationships thanks to the bridging power of communication technologies. We can also be entertained and informed in ways that were unimaginable a century ago thanks to these technologies—and they continue to evolve and change before our eyes.

This text provides a snapshot of the state of technologies in our society. The individual chapter authors have compiled facts and figures from hundreds of sources to provide the latest information on more than two dozen communication technologies. Each discussion explains the roots and evolution, recent developments, and current status of the technology as of mid-2018. In discussing each technology, we address them from a systematic perspective, looking at a range of factors beyond hardware.

The goal is to help you analyze emerging technologies and be better able to predict which ones will succeed and which ones will fail. That task is more difficult to achieve than it sounds. Let’s look at an example of how unpredictable technology can be.

The Alphabet Tale

As this book goes to press in mid-2018, Alphabet, the parent company of Google, is the most valuable media company in the world in terms of market capitalization (the total value of all shares of stock held in the company). To understand how Alphabet attained that lofty position, we have to go back to the late 1990s, when commercial applications of the Internet were taking off. There was no question in the minds of engineers and futurists that the Internet was going to revolutionize the delivery of information, entertainment, and commerce. The big question was how it was going to happen.

Those who saw the Internet as a medium for information distribution knew that advertiser support would be critical to its long-term financial success. They knew that they could always find a small group willing to pay for content, but the majority of people preferred free content. To become a mass medium similar to television, newspapers, and magazines, an Internet advertising industry was needed.

At that time, most Internet advertising was banner ads—horizontal display ads that stretched across most of the screen to attract attention, but took up very little space on the screen. The problem was that most people at that time accessed the Internet using slow, dial-up connections, so advertisers were limited in what they could include in these banners to about a dozen words of text and simple graphics. The dream among advertisers was to be able to use rich media, including full-motion video, audio, animation, and every other trick that makes television advertising so successful.

When broadband Internet access started to spread, advertisers were quick to add rich media to their banners, as well as create other types of ads using graphics, video, and sound. These ads were a little more effective, but many Internet users did not like the intrusive nature of rich media messages.

At about the same time, two Stanford students, Sergey Brin and Larry Page, had developed a new type of search engine, Google, that ranked results on the basis of how often content was referred to or linked from other sites, allowing their computer algorithms to create more robust and relevant search results (in most cases) than having a staff of people indexing Web content. What they needed was a way to pay for the costs of the servers and other technology.

According to Vise & Malseed (2006), their budget did not allow the company, then known as Google, to create and distribute rich media ads. They could do text ads, but they decided to do them differently from other Internet advertising, using computer algorithms to place these small text ads on the search results that were most likely to give the advertisers results. With a credit card, anyone could use this “AdWords” service, specifying the search terms they thought should display their ads, writing the brief ads (less than 100 characters total—just over a dozen words), and even specifying how much they were willing to pay every time someone clicked on their ad. Even more revolutionary, the Google team decided that no one should have to pay for an ad unless a user clicked on it.

For advertisers, it was as close to a no-lose proposition as they could find. Advertisers did not have to pay unless a person was interested enough to click on the ad. They could set a budget that Google computers could follow, and Google provided a control panel for advertisers that gave a set of measures that was a dream for anyone trying to make a campaign more effective. These measures indicated not only the overall effectiveness of the ad, but also the effectiveness of each message, each keyword, and every part of every campaign.

The result was remarkable. Google’s share of the search market was not that much greater than the companies that had held the #1 position earlier, but Google was making money—lots of money—from these little text ads. Wall Street investors noticed, and, once Google went public, investors bid up the stock price, spurred by increases in revenues and a very large profit margin. Today, Google’s parent company, renamed Alphabet, is involved in a number of other ventures designed to aggregate and deliver content ranging from text to full-motion video, but its little text ads on its Google search engine are still the primary revenue generator.

In retrospect, it was easy to see why Google was such a success. Their little text ads were effective because of context—they always appeared where they would be the most effective. They were not intrusive, so people did not mind the ads on Google pages, and later on other pages that Google served ads to through its “content network.” Plus, advertisers had a degree of control, feedback, and accountability that no advertising medium had ever offered before (Grant & Wilkinson, 2007).

So what lessons should we learn from this story? Advertisers have their own set of lessons, but there are a separate set of lessons for those wishing to understand new media. First, no matter how insightful, no one is ever able to predict whether a technology will succeed or fail. Second, success can be due as much to luck as to careful, deliberate planning and investment. Third, simplicity matters—there are few advertising messages as simple as the little text ads you see when doing a Google search.

The Alphabet tale provides an example of the utility of studying individual companies and industries, so the focus throughout this book is on individual technologies. These individual snapshots, however, comprise a larger mosaic representing the communication networks that bind individuals together and enable them to function as a society. No single technology can be understood without understanding the competing and complementary technologies and the larger social environment within which these technologies exist. As discussed in the following section, all of these factors (and others) have been considered in preparing each chapter through application of the “technology ecosystem.” Following this discussion, an overview of the remainder of the book is presented.

The Communication Technology Ecosystem

The most obvious aspect of communication technology is the hardware—the physical equipment related to the technology. The hardware is the most tangible part of a technology system, and new technologies typically spring from developments in hardware. However, understanding communication technology requires more than just studying the hardware. One of the characteristics of today’s digital technologies is that most are based upon computer technology, requiring instructions and algorithms more commonly known as “software.”

In addition to understanding the hardware and software of the technology, it is just as important to understand the content communicated through the technology system. Some consider the content as another type of software. Regardless of the terminology used, it is critical to understand that digital technologies require a set of instructions (the software) as well as the equipment and content.

The Communication Technology Ecosystem

Source: A. E. Grant

The hardware, software, and content must also be studied within a larger context. Rogers’ (1986) definition of “communication technology” includes some of these contextual factors, defining it as “the hardware equipment, organizational structures, and social values by which individuals collect, process, and exchange information with other individuals” (p. 2). An even broader range of factors is suggested by Ball-Rokeach (1985) in her media system dependency theory, which suggests that communication media can be understood by analyzing dependency relations within and across levels of analysis, including the individual, organizational, and system levels. Within the system level, Ball-Rokeach identifies three systems for analysis: the media system, the political system, and the economic system.

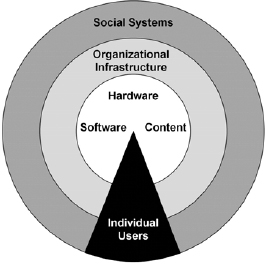

These two approaches have been synthesized into the “Technology Ecosystem” illustrated in Figure 1.1. The core of the technology ecosystem consists of the hardware, software, and content (as previously defined). Surrounding this core is the organizational infrastructure: the group of organizations involved in the production and distribution of the technology. The next level moving outwards is the system level, including the political, economic, and media systems, as well as other groups of individuals or organizations serving a common set of functions in society. Finally, the individual users of the technology cut across all of the other areas, providing a focus for understanding each one. The basic premise of the technology ecosystem is that all areas of the ecosystem interact and must be examined in order to understand a technology.

(The technology ecosystem is an elaboration of the “umbrella perspective” (Grant, 2010) that was explicated in earlier editions of this book to illustrate the elements that need to be studied in order to understand communication technologies.)

Adding another layer of complexity to each of the areas of the technology ecosystem is also helpful. In order to identify the impact that each individual characteristic of a technology has, the factors within each area of the ecosystem may be identified as “enabling,” “limiting,” “motivating,” and “inhibiting” depending upon the role they play in the technology’s diffusion.

Enabling factors are those that make an application possible. For example, the fact that the coaxial cable used to deliver traditional cable television can carry dozens of channels is an enabling factor at the hardware level. Similarly, the decision of policy makers to allocate a portion of the radio frequency spectrum for cellular telephony is an enabling factor at the system level (political system). One starting point to use in examining any technology is to make a list of the underlying factors from each area of the technology ecosystem that make the technology possible in the first place.

Limiting factors are the opposite of enabling factors; they are those factors that create barriers to the adoption or impacts of a technology. A great example is related to the cellular telephone illustration in the previous paragraph. The fact that the policy makers discussed above initially permitted only two companies to offer cellular telephone service in each market was a system level limitation on that technology. The later introduction of digital technology made it possible for another four companies to compete for mobile phone service. To a consumer, six telephone companies may seem to be more than is needed, but to a start-up company wanting to enter the market, this system-level factor represents a definite limitation. Again, it is useful to apply the technology ecosystem to create a list of factors that limit the adoption, use, or impacts of any specific communication technology.

Motivating factors are a little more complicated. They are those factors that provide a reason for the adoption of a technology. Technologies are not adopted just because they exist. Rather, individuals, organizations, and social systems must have a reason to take advantage of a technology. The desire of local telephone companies for increased profits, combined with the fact that growth in providing local telephone service is limited, is an organizational factor motivating the telcos to enter the markets for new communication technologies. Individual users desiring information more quickly can be motivated to adopt electronic information technologies. If a technology does not have sufficient motivating factors for its use, it cannot be a success.

Inhibiting factors are the opposite of motivating ones, providing a disincentive for adoption or use of a communication technology. An example of an inhibiting factor at the organizational level might be a company’s history of bad customer service. Regardless of how useful a new technology might be, if customers don’t trust a company, they are not likely to purchase its products or services. One of the most important inhibiting factors for most new technologies is the cost to individual users. Each potential user must decide whether the cost is worth the service, considering their budget and the number of competing technologies. Competition from other technologies is one of the biggest barriers any new (or existing) technology faces. Any factor that works against the success of a technology can be considered an inhibiting factor. As you might guess, there are usually more inhibiting factors for most technologies than motivating ones. And if the motivating factors are more numerous and stronger than the inhibiting factors, it is an easy bet that a technology will be a success.

All four factors—enabling, limiting, motivating, and inhibiting—can be identified at the individual user, organizational, content, and system levels. However, hardware and software can only be enabling or limiting; by themselves, hardware and software do not provide any motivating factors. The motivating factors must always come from the messages transmitted or one of the other areas of the ecosystem.

The final dimension of the technology ecosystem relates to the environment within which communication technologies are introduced and operate. These factors can be termed “external” factors, while ones relating to the technology itself are “internal” factors. In order to understand a communication technology or be able to predict how a technology will diffuse, both internal and external factors must be studied.

Applying the Communication Technology Ecosystem

The best way to understand the communication technology ecosystem is to apply it to a specific technology. One of the fastest diffusing technologies discussed later in this book is the “personal assistant,” such as the Amazon Alexa or Google Home—these devices provide a great application of the communication technology ecosystem.

Let’s start with the hardware. Most personal assistants are small or medium-sized units, designed to sit on a shelf or table. Studying the hardware reveals that the unit contains multiple speakers, a microphone, some computer circuitry, and a radio transmitter and receiver. Studying the hardware, we can get clues about the functionality of the device, but the key to the functionality is the software.

The software related to the personal assistant enables conversion of speech heard by the microphone into text or other commands that connect to another set of software designed to fulfill the commands given to the system. From the perspective of the user, it doesn’t matter whether the device converts speech to commands or whether the device transmits speech to a central computer where the translation takes place—the device is designed so that it doesn’t matter to the user. The important thing that becomes apparent is that the hardware used by the system extends well beyond the device through the Internet to servers that are programmed to deliver answers and content requested through the personal assistant.

So, who owns these servers? To answer that question, we have to look at the organizational infrastructure. It is apparent that there are two distinct sets of organizations involved—one set that makes and distributes the devices themselves to the public and the other that provides the back-end processing power to find answers and deliver content. For the Amazon Alexa, Amazon has designed and arranged for the manufacture of the device. (Note that few companies specialize in making hardware; rather, most communication hardware is made by companies that specialize in manufacturing on a contract basis.) Amazon also owns and controls the servers that interpret and seek answers to questions and commands. But to get to those servers, the commands have to first pass through cable or phone networks owned by other companies, with answers or content provided by servers on the Internet owned by still other companies. At this point, it is helpful to examine the economic relationships among the companies involved. The users’ Internet Service Provider (ISP) passes all commands and content from the home device to the cloud-based servers, which are, in turn, connected to servers owned by other companies that deliver content.

So, if a person requests a weather forecast, the servers connect to a weather service for content. A person might also request music, finding themselves connected to Amazon’s own music service or to another service such as Pandora or Sirius/XM. A person ordering a pizza will have their message directed to the appropriate pizza delivery service, with the only content returned being a confirmation of the order, perhaps with status updates as the order is fulfilled.

The pizza delivery example is especially important because it demonstrates the economics of the system. The servers used are expensive to purchase and operate, so the company that designs and sells personal assistants has a motivation to contract with individual pizza delivery services to pay a small commission every time someone orders a pizza. Extending this example to multiple other services will help you understand why some services are provided for free but others must be paid, with the pieces of the system working together to spread revenue to all of the companies involved.

The point is that it is not possible to understand the personal assistant without understanding all of the organizations implicated in the operation of the device. And if two organizations decide not to cooperate with each other, content or service may simply not be available.

The potential conflicts among these organizations can move our attention to the next level of the ecosystem, the social system level. The political system, for example, has the potential to enable services by allowing or encouraging collaboration among organizations. Or it can do the opposite, limiting or inhibiting cooperation with regulations. (Net neutrality, discussed in Chapter 5, is a good example of the role played by the political system in enabling or limiting capabilities of technology.) The system of retail stores enables distribution of the personal assistant devices to local retail stores, making it easier for a user to become an “adopter” of the device.

Studying the personal assistant also helps understand the enabling and limiting functions. For example, the fact that Amazon has programmed the Alexa app to accept commands in dozens of languages from Spanish to Klingon is an enabling factor, but the fact that there are dozens of other languages that have not been programming is definitely a limiting factor.

Similarly, the ease of ordering a pizza through your personal assistant is a motivating factor, but having your device not understand your commands is an inhibiting factor.

Finally, examination of the environment gives us more information, including competitive devices, public sentiment, and general economic environment.

All of those details help us to understand how personal assistants work and how companies can profit in many different ways from their use. But we can’t fully understand the role that these devices play in the lives of their users without studying the individual user. We can examine what services are used, why they are used, how often they are used, the impacts of their use, and much more.

Applying the Communication Technology Ecosystem thus allows us to look at a technology, its uses, and its effects by giving a multidimensional perspective that provides a more comprehensive insight than we would get from just examining the hardware or software.

Each communication technology discussed in this book has been analyzed using the technology ecosystem to ensure that all relevant factors have been included in the discussions. As you will see, in most cases, organizational and system-level factors (especially political factors) are more important in the development and adoption of communication technologies than the hardware itself. For example, political forces have, to date, prevented the establishment of a single world standard for high-definition television (HDTV) production and transmission. As individual standards are selected in countries and regions, the standard selected is as likely to be the product of political and economic factors as of technical attributes of the system.

Organizational factors can have similar powerful effects. For example, as discussed in Chapter 4, the entry of a single company, IBM, into the personal computer business in the early 1980s resulted in fundamental changes in the entire industry, dictating standards and anointing an operating system (MS-DOS) as a market leader. Finally, the individuals who adopt (or choose not to adopt) a technology, along with their motivations and the manner in which they use the technology, have profound impacts on the development and success of a technology following its initial introduction.

Perhaps the best indication of the relative importance of organizational and system-level factors is the number of changes individual authors made to the chapters in this book between the time of the initial chapter submission in January 2018 and production of the final, camera-ready text in April 2018. Very little new information was added regarding hardware, but numerous changes were made due to developments at the organizational and system levels.

To facilitate your understanding of all of the elements related to the technologies explored, each chapter in this book has been written from the perspective of the technology ecosystem. The individual writers have endeavored to update developments in each area to the extent possible in the brief summaries provided. Obviously, not every technology experienced developments in each area of the ecosystem, so each report is limited to areas in which relatively recent developments have taken place.

Why Study New Technologies?

One constant in the study of media is that new technologies seem to get more attention than traditional, established technologies. There are many reasons for the attention. New technologies are more dynamic and evolve more quickly, with greater potential to cause change in other parts of the media system. Perhaps the reason for our attention is the natural attraction that humans have to motion, a characteristic inherited from our most distant ancestors.

There are a number of other reasons for studying new technologies. Maybe you want to make a lot of money—and there is a lot of money to be made (and lost!) on new technologies. If you are planning a career in the media, you may simply be interested in knowing how the media are changing and evolving, and how those changes will affect your career.

Or you might want to learn lessons from the failure of new communication technologies so you can avoid failure in your own career, investments, etc. Simply put, the majority of new technologies introduced do not succeed in the market. Some fail because the technology itself was not attractive to consumers (such as the 1980s’ attempt to provide AM stereo radio). Some fail because they were far ahead of the market, such as Qube, the first interactive cable television system, introduced in the 1970s. Others failed because of bad timing or aggressive marketing from competitors that succeeded despite inferior technology.

The final reason for studying new communication technologies is to identify patterns of adoption, effects, economics, and competition so that we can be prepared to understand, use, and/or compete with the next generation of media. Virtually every new technology discussed in this book is going to be one of those “traditional, established technologies” in a few short years, but there will always be another generation of new media to challenge the status quo.

Overview of Book

The key to getting the most out of this book is therefore to pay as much attention as possible to the reasons that some technologies succeed and others fail. To that end, this book provides you with a number of tools you can apply to virtually any new technology that comes along. These tools are explored in the first five chapters, which we refer to as the Communication Technology Fundamentals. You might be tempted to skip over these to get to the latest developments about the individual technologies that are making an impact today, but you will be much better equipped to learn lessons from these technologies if you are armed with these tools.

The first of these is the “technology ecosystem” discussed previously that broadens attention from the technology itself to the users, organizations, and system surrounding that technology. To that end, each of the technologies explored in this book provides details about all of the elements of the ecosystem.

Of course, studying the history of each technology can help you find patterns and apply them to different technologies, times, and places. In addition to including a brief history of each technology, the next chapter, A History of Communication Technologies, provides a broad overview of most of the technologies discussed later in the book, allowing comparisons along a number of dimensions: the year introduced, growth rate, number of current users, etc. This chapter highlights commonalties in the evolution of individual technologies, as well as presents the “big picture” before we delve into the details. By focusing on the number of users over time, this chapter also provides a useful basis of comparison across technologies.

Another useful tool in identifying patterns across technologies is the application of theories related to new communication technologies. By definition, theories are general statements that identify the underlying mechanisms for adoption and effects of these new technologies. Chapter 3 provides an overview of a wide range of these theories and provides a set of analytic perspectives that you can apply to both the technologies in this book and any new technologies that follow.

The structure of communication industries is then addressed in Chapter 4. This chapter then explores the complexity of organizational relationships, along with the need to differentiate between the companies that make the technologies and those that sell the technologies. The most important force at the system level of the ecosystem, regulation, is introduced in Chapter 5.

These introductory chapters provide a structure and a set of analytic tools that define the study of communication technologies. Following this introduction, the book then addresses the individual technologies.

The technologies discussed in this book are organized into three sections: Electronic Mass Media, Computers & Consumer Electronics, and Networking Technologies. These three are not necessarily exclusive; for example, Digital Signage could be classified as either an electronic mass medium or a computer technology. The ultimate decision regarding where to put each technology was made by determining which set of current technologies most closely resemble the technology. Thus, Digital Signage was classified with electronic mass media. This process also locates the discussion of a cable television technology—cable modems—in the Broadband and Home Networks chapter in the Networking Technologies section.

Each chapter is followed by a brief bibliography that represents a broad overview of literally hundreds of books and articles that provide details about these technologies. It is hoped that the reader will not only use these references but will examine the list of source material to determine the best places to find newer information since the publication of this Update.

To help you find your place in this emerging technology ecosystem, each technology chapter includes a paragraph or two discussing how you can get a job in that area of technology. And to help you imagine the future, some authors have also added their prediction of what that technology will be like in 2033—or fifteen years after this book is published. The goal is not to be perfectly accurate, but rather to show you some of the possibilities that could emerge in that time frame.

Most of the technologies discussed in this book are continually evolving. As this book was completed, many technological developments were announced but not released, corporate mergers were under discussion, and regulations had been proposed but not passed. Our goal is for the chapters in this book to establish a basic understanding of the structure, functions, and background for each technology, and for the supplementary Internet site to provide brief synopses of the latest developments for each technology. (The address for the website is www.tfi.com/ctu.)

The final chapter returns to the “big picture” presented in this book, attempting to place these discussions in a larger context, exploring the process of starting a company to exploit or profit from these technologies. Any text such as this one can never be fully comprehensive, but ideally this text will provide you with a broad overview of the current developments in communication technology.

Bibliography

Ball-Rokeach, S. J. (1985). The origins of media system dependency: A sociological perspective. Communication Research, 12 (4), 485-510.

Beniger, J. (1986). The control revolution. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Grant, A. E. (2010). Introduction to communication technologies. In A. E. Grant & J. H. Meadows (Eds.) Communication Technology Update and Fundamentals (12th ed). Boston: Focal Press.

Grant, A. E. & Wilkinson, J. S. (2007, February). Lessons for communication technologies from Web advertising. Paper presented to the Mid-Winter Conference of the Association of Educators in Journalism and Mass Communication, Reno.

Rogers, E. M. (1986). Communication technology: The new media in society. New York: Free Press.

Vise, D. & Malseed, M. (2006). The Google story: Inside the hottest business, media, and technology success of our time. New York: Delta.

_______________

* J. Rion McKissick Professor of Journalism, School of Journalism and Mass Communications, University of South Carolina (Columbia, South Carolina).