4

The Structure of the Communication Industries

The first factor that many people consider when studying communication technologies is changes in the equipment and use of the technology. But, as discussed in Chapter 1, it is equally important to study and understand all areas of the technology ecosystem. In editing the Communication Technology Update for 25 years, one factor stands out as having the greatest amount of short-term change: the organizational infrastructure of the technology.

The continual flux in the organizational structure of communication industries makes this area the most dynamic area of technology to study. “New” technologies that make a major impact come along only a few times a decade. New products that make a major impact come along once or twice a year. Organizational shifts are constantly happening, making it almost impossible to know all of the players at any given time.

Even though the players are changing, the organizational structure of communication industries is relatively stable. The best way to understand the industry, given the rapid pace of acquisitions, mergers, startups, and failures, is to understand its organizational functions. This chapter addresses the organizational structure and explores the functions of those industries, which will help you to understand the individual technologies discussed throughout this book.

In the process of using organizational functions to analyze specific technologies, you must consider that these functions cross national as well as technological boundaries. Most hardware is designed in one country, manufactured in another, and sold around the globe. Although there are cultural and regulatory differences addressed in the individual technology chapters later in the book, the organizational functions discussed in this chapter are common internationally.

What’s in a Name? The AT&T Story

A good illustration of the importance of understanding organizational functions comes from analyzing the history of AT&T, one of the biggest names in communication of all time. When you hear the name “AT&T,” what do you think of? Your answer probably depends on how old you are and where you live. If you live in Florida, you may know AT&T as your local phone company. In New York, it is the name of one of the leading mobile telephone companies. If you are older than 60, you might think of the company’s old nickname “Ma Bell.”

The Birth of AT&T

In the study of communication technology over the last century, no name is as prominent as AT&T. But the company known today as AT&T is an awkward descendent of the company that once held a monopoly on long-distance telephone service and a near monopoly on local telephone service through the first four decades of the 20th century. The AT&T story is a story of visionaries, mergers, divestiture, and rebirth.

Alexander Graham Bell invented his version of the telephone in 1876, although historians note that he barely beat his competitors to the patent office. His invention soon became an important force in business communication, but diffusion of the telephone was inhibited by the fact that, within 20 years, thousands of entrepreneurs established competing companies to provide telephone service in major cities. Initially, these telephone systems were not interconnected, making the choice of telephone company a difficult one, with some businesses needing two or more local phone providers to connect with their clients.

The visionary who solved the problem was Theodore Vail, who realized that the most important function was the interconnection of these telephone companies. Vail led American Telephone & Telegraph to provide the needed interconnection, negotiating with the U.S. government to provide “universal service” under heavy regulation in return for the right to operate as a monopoly. Vail brought as many local telephone companies as he could into AT&T, which evolved under the eye of the federal government as a behemoth with three divisions:

As a monopoly that was generally regulated on a rate-of-return basis (making a fixed profit percentage), AT&T had little incentive—other than that provided by regulators—to hold down costs. The more the company spent, the more it had to charge to make its profit, which grew in proportion with expenses. As a result, the U.S. telephone industry became the envy of the world, known for “five nines” of reliability; that is, the telephone network was designed to be available to users 99.999% of the time. The company also spent millions every year on basic research, with its Bell Labs responsible for the invention of many of the most important technologies of the 20th century, including the transistor and the laser.

Divestiture

The monopoly suffered a series of challenges in the 1960s and 1970s that began to break AT&T’s monopoly control. First, AT&T lost a suit brought by the Hush-a-Phone company, which made a plastic mouthpiece that fit over the AT&T telephone mouthpiece to make it easier to hear a call made in a noisy area (Hush-a-phone v. AT&T, 1955; Hush-a-phone v. U.S., 1956). (The idea of a company having to win a lawsuit in order to sell such an innocent item seems frivolous today, but this suit was the first major crack in AT&T’s monopoly armor.) Soon, MCI won a suit to provide long-distance service between St. Louis and Chicago, allowing businesses to bypass AT&T’s long lines (Microwave Communications, Inc., 1969).

Since the 1920s, the Department of Justice (DOJ) had challenged aspects of AT&T’s monopoly control, earning a series of consent decrees to limit AT&T’s market power and constrain corporate behavior. By the 1970s, it was clear to the antitrust attorneys that AT&T’s ownership of Western Electric inhibited innovation, and the DOJ attempted to force AT&T to divest itself of its manufacturing arm. In a surprising move, AT&T proposed a different divestiture, spinning off all of its local telephone companies into seven new “Baby Bells,” keeping the now-competitive long distance service and manufacturing arms. The DOJ agreed, and a new AT&T was born (Dizard, 1989).

Cycles of Expansion and Contraction

After divestiture, the leaner, “new” AT&T attempted to compete in many markets with mixed success; AT&T long distance service remained a national leader, but few bought overpriced AT&T personal computers. In the meantime, the seven Baby Bells focused on serving their local markets, with most named after the region they served. Nynex served New York and the extreme northeast states, Bell Atlantic served the mid-Atlantic states, BellSouth served the southeastern states, Ameritech served the midwest, Southwestern Bell served south central states, U S West served a set of western states, and Pacific Telesis served California and the far western states.

Over the next two decades, consolidation occurred among these Baby Bells. Nynex and Bell Atlantic merged to create Verizon. U S West was purchased by Qwest Communication and renamed after its new parent, which was, in turn, acquired by CenturyLink in 2010. As discussed below, Southwestern Bell was the most aggressive Baby Bell, ultimately reuniting more than half of the Baby Bells.

In the meantime, AT&T entered the 1990s with a repeating cycle of growth and decline. It acquired NCR Computers in 1991 and McCaw Communications (then the largest U.S. cellular phone company) in 1993. Then, in 1995, it divested itself of its manufacturing arm (which became Lucent Technologies) and the computer company (which took the NCR name). It grew again in 1998 by acquiring TCI, the largest U.S. cable TV company, renaming it AT&T Broadband, and then acquired another cable company, MediaOne. In 2001, it sold AT&T Broadband to Comcast, and it spun off its wireless interests into an independent company (AT&T Wireless), which was later acquired by Cingular (a wireless phone company co-owned by Baby Bells SBC and BellSouth) (AT&T, 2008).

The only parts of AT&T remaining were the long distance telephone network and the business services, resulting in a company that was a fraction of the size of the AT&T behemoth that had a near monopoly on telephony in the United States two decades earlier.

Under the leadership of Edward Whitacre, Southwestern Bell became one of the most formidable players in the telecommunications industry. With a visionary style not seen in the telephone industry since the days of Theodore Vail, Whitacre led Southwestern Bell to acquire Baby Bells Pacific Telesis and Ameritech (and a handful of other, smaller telephone companies), renaming itself SBC. Ultimately, SBC merged with BellSouth and purchased what was left of AT&T, then renamed the company AT&T, an interesting case comparable to a child adopting its parent.

Today’s AT&T is a dramatically different company with a dramatically different culture than its parent, but the company serves most of the same markets in a much more competitive environment. The lesson is that it is not enough to know the technologies or the company names; you also have to know the history of both in order to understand the role that a company plays in the marketplace.

Functions within the Industries

The AT&T story is an extreme example of the complexity of communication industries. These industries are easier to understand by breaking their functions into categories that are common across most of the segments of these industries. Let’s start with the heart of the technology ecosystem introduced in Chapter 1, the hardware, software, and content.

For this discussion, let’s use the same definitions used in Chapter 1, with hardware referring to the physical equipment used, software referring to instructions used by the hardware to manipulate content, and content referring to the messages transmitted using these technologies. Some companies produce both hardware and software, ensuring compatibility between the equipment and programming, but few companies produce both equipment and content.

The next distinction has to be made between production and distribution of both equipment and content. As these names imply, companies involved in production engage in the manufacture of equipment or content, and companies involved in distribution are the intermediaries between production and consumers. It is a common practice for some companies to be involved in both production and distribution, but, as discussed below, a large number of companies choose to focus on one or the other.

These two dimensions interact, resulting in separate functions of equipment production, equipment distribution, content production, and content distribution. As discussed below, distribution can be further broken down into national and local distribution. The following section introduces these dimensions, which then help us identify the role played by specific companies in communication industries.

One other note: These functions are hierarchical, with production coming before distribution in all cases. Let’s say you are interested in creating a new type of telephone, perhaps a “high-definition telephone.” You know that there is a market, and you want to be the person who sells it to consumers. But you cannot do so until someone first makes the device. Production always comes before distribution, but you cannot have successful production unless you also have distribution—hence the hierarchy in the model. Figure 4.1 illustrates the general pattern, using the U.S. television industry as an example.

Hardware

When you think of hardware, you typically envision the equipment you handle to use a communication technology. But it is also important to note that there is a second type of hardware for most communication industries—the equipment used to make the content. Although most consumers do not deal with this equipment, it plays a critical role in the system.

Content Production Hardware

Production hardware is usually more expensive and specialized than other types. Examples in the television industry include TV cameras, microphones, and editing equipment. A successful piece of production equipment might sell only a few hundred or a few thousand units, compared with tens of thousands to millions of units for consumer equipment. The profit margin on production equipment is usually much higher than on consumer equipment, making it a lucrative market for manufacturing companies.

Consumer Hardware

Consumer hardware is the easiest to identify. It includes anything from a television to a mobile phone or DirecTV satellite dish. A common term used to identify consumer hardware in consumer electronics industries is CPE, which stands for customer premises equipment. An interesting side note is that many companies do not actually make their own products, but instead hire manufacturing facilities to make products they design, shipping them directly to distributors. For example, Microsoft does not manufacture the Xbox One; Flextronics and Foxconn do. As you consider communication technology hardware, consider the lesson from Chapter 1—people are not usually motivated to buy equipment because of the equipment itself, but because of the content it enables, from the conversations (voice and text!) on a wireless phone to the information and entertainment provided by a high-definition television (HDTV) receiver.

Distribution

After a product is manufactured, it has to get to consumers. In the simplest case, the manufacturer sells directly to the consumer, perhaps through a company-owned store or a website. In most cases, however, a product will go through multiple organizations, most often with a wholesaler buying it from the manufacturer and selling it, with a mark-up, to a retail store, which also marks up the price before selling it to a consumer. The key point is that few manufacturers control their own distribution channels, instead relying on other companies to get their products to consumers.

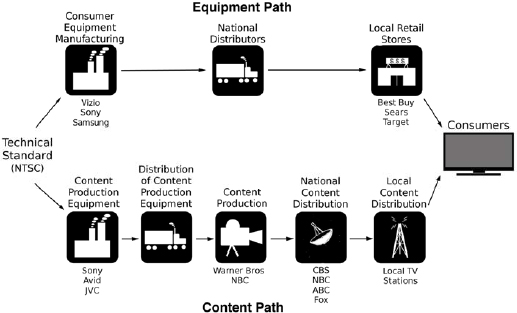

Structure of the Traditional Broadcast TV Industry

Source: R. Grant & G. Martin

Content Path: Production and Distribution

The process that media content goes through to get to consumers is a little more complicated than the process for hardware. The first step is the production of the content itself. Whether the product is movies, music, news, images, etc., some type of equipment must be manufactured and distributed to the individuals or companies who are going to create the content. (That hardware production and distribution goes through a similar process to the one discussed above.) The content must then be created, duplicated, and distributed to consumers or other end users.

The distribution process for media content/software follows the same pattern for hardware. Usually there will be multiple layers of distribution, a national wholesaler that sells the content to a local retailer, which in turn sells it to a consumer.

Disintermediation

Although many products go through multiple layers of distribution to get to consumers, information technologies have also been applied to reduce the complexity of distribution. The process of eliminating layers of distribution is called disintermediation (Kottler & Keller, 2005); examples abound of companies that use the Internet to get around traditional distribution systems to sell directly to consumers.

Netflix is a great example. Traditionally, digital videodiscs (DVDs) of a movie were sold by the studio to a national distributor, which then delivered them to thousands of individual movie rental stores, which, in turn rented or sold them to consumers. (Note: The largest video stores bought directly from the studio, handling both national and local distribution.)

Netflix cut one step out of the distribution process, directly bridging the movie studio and the consumer. (As discussed below, iTunes serves the same function for the music industry, simplifying music distribution.) The result of getting rid of one middleman is greater profit for the companies involved, lower costs to the consumer, or both. The “disruption,” in this case, was the demise of the rental store.

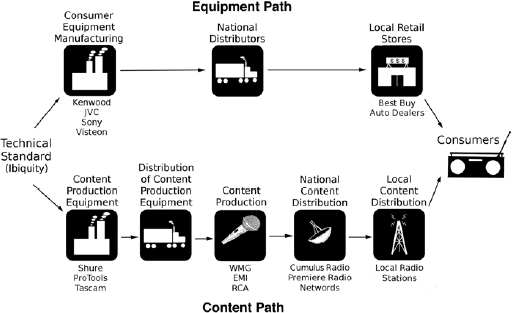

Illustrations: HDTV and HD Radio

The emergence of digital broadcasting provides two excellent illustrations of the complexity of the organizational structure of media industries. HDTV and its distant cousin HD radio have had a difficult time penetrating the market because of the need for so many organizational functions to be served before consumers can adopt the technology.

Let’s start with the simpler one: HD radio. As illustrated in Figure 4.2, this technology allows existing radio stations to broadcast their current programming (albeit with much higher fidelity), so no changes are needed in the software production area of the model. The only change needed in the software path is that radio stations simply need to add a digital transmitter. The complexity is related to the consumer hardware needed to receive HD radio signals. One set of companies makes the radios, another distributes the radios to retail stores and other distribution channels, then stores and distributors have to agree to sell them.

The radio industry has therefore taken an active role in pushing diffusion of HD radios throughout the hardware path. In addition to airing thousands of radio commercials promoting HD radio, the industry is promoting distribution of HD radios in new cars (because so much radio listening is done in automobiles).

As discussed in Chapter 8, adoption of HD radio has begun, but has been slow because listeners see little advantage in the new technology. However, if the number of receivers increases, broadcasters will have a reason to begin using the additional channels available with HD. As with FM radio, programming and receiver sales have to both be in place before consumer adoption takes place. Also, as with FM, the technology may take decades to take off.

The same structure is inherent in the adoption of HDTV, as illustrated in Figure 4.3. Before the first consumer adoption could take place, both programming and receivers (consumer hardware) had to be available. Because a high percentage of primetime television programming was recorded on 35mm film at the time HDTV receivers first went on sale in the United States, that programming could easily be transmitted in high-definition, providing a nucleus of available programming. On the other hand, local news and network programs shot on video required entirely new production and editing equipment before they could be distributed to consumers in high-definition.

Structure of the HD Radio Industry

Source: R. Grant & G. Martin

Structure of the HDTV Industry

Source: R. Grant & G. Martin

As discussed in Chapter 6, the big force behind the diffusion of HDTV and digital TV was a set of regulations issued by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) that first required stations in the largest markets to begin broadcasting digital signals, then required that all television receivers include the capability to receive digital signals, and finally required that all full-power analog television broadcasting cease on June 12, 2009. In short, the FCC implemented mandates ensuring production and distribution of digital television, easing the path toward both digital TV and HDTV.

As you will read in Chapter 6, this cycle will repeat itself over the next few years as the television industry adopts an improved, but incompatible, format known as UltraHDTV (or 4K).

The success of this format will require modifications of virtually all areas of the television system diagrammed in Figure 4.3, with new production equipment manufactured and then used to produce content in the new format, and then distributed to consumers—who are not likely to buy until all of these functions are served.

From Target to iTunes

One of the best examples of the importance of distribution comes from an analysis of the popular music industry. In the last century, music was recorded on physical media such as CDs and audio tapes and then shipped to retail stores for sale directly to consumers. At one time, the top three U.S. retailers of music were Target, Walmart, and Best Buy.

Once digital music formats that could be distributed over the Internet were introduced in the late 1990s, dozens of start-up companies created online stores to sell music directly to consumers. The problem was that few of these online stores offered the top-selling music. Record companies were leery of the lack of control they had over digital distribution, leaving most of these companies to offer a marginal assortment of music.

The situation changed in 2003 when Apple introduced the iTunes store to provide content for its iPods, which had sold slowly since appearing on the market in 2001. Apple obtained contracts with major record companies that allowed them to provide most of the music that was in high demand.

Initially, record companies resisted the iTunes distribution model that allowed a consumer to buy a single song for $0.99; they preferred that a person have to buy an entire album of music for $13 to $20 to get the one or two songs they wanted.

Record company delays spurred consumers to create and use file-sharing services that allowed listeners to get the music for free—and the record companies ended up losing billions of dollars. Soon, the $0.99 iTunes model began to look very attractive to the record companies, and they trusted Apple’s digital rights management system to protect their music.

Today, as discussed in Chapter 8, iTunes is the number one music retailer in the United States. The music is similar, but the distribution of music today is dramatically different from what it was in 2001. The change took years of experimentation, and the successful business model that emerged required cooperation from dozens of separate companies serving different roles in production and distribution.

Two more points should be made regarding distribution. First, there is typically more profit potential and less risk in being a distributor than a creator (of either hardware or software) because the investment is less and distributors typically earn a percentage of the value of what they sell. Second, distribution channels can become very complicated when multiple layers of distribution are involved; the easiest way to unravel these layers is simply to “follow the money.”

Importance of Distribution

As the above discussion indicates, distributors are just as important to new technologies as manufacturers and service providers. When studying these technologies, and the reasons for success or failure, the distribution process (including economics) must be examined as thoroughly as the product itself.

Diffusion Threshold

Analysis of the elements in Figure 4.1 reveals an interesting conundrum—there cannot be any consumer adoption of a new technology until all of the production and distribution functions are served, along both the hardware and software paths.

This observation adds a new dimension to Rogers’ (2003) diffusion theory, discussed in the previous chapter. The point at which all functions are served has been identified as the “diffusion threshold,” the point at which diffusion of the technology can begin (Grant, 1990).

It is easier for a technology to “take off” and begin diffusing if a single company provides a number of different functions, perhaps combining production and distribution, or providing both national and local distribution. The technical term for owning multiple functions in an industry is “vertical integration,” and a vertically integrated company has a disproportionate degree of power and control in the marketplace.

Vertical integration is easier said than done, however, because the “core competencies” needed for production and distribution are so different. A company that is great at manufacturing may not have the resources needed to sell the product to end consumers.

Let’s consider the next generation of television, UltraHD, again. A company such as Vizio might handle the first level of distribution, from the manufacturing plant to the retail store, but they do not own and operate their own stores—that is a very different business. They are certainly not involved in owning the television stations or cable channels that distribute UltraHD programming; that function is served by another set of organizations.

In order for UltraHD to become popular, one organization (or set of organizations) has to make the television receivers, another has to get those televisions into stores, a third has to operate the stores, a fourth has to make UltraHD cameras and technical equipment to produce content, and a fifth has to package and distribute the content to viewers, through the Internet using Internet protocol television (IPTV), cable television systems, or over-the-air.

Most companies that would like to grow are more interested in applying their core competencies by buying up competitors and commanding a greater market share, a process known as “horizontal integration.” For example, it makes more sense for a company that makes televisions to grow by making other electronics rather than by buying television stations. Similarly, a company that already owns television stations will probably choose to grow by buying more television stations or cable networks rather than by starting to make and sell television receivers.

The complexity of the structure of most communication industries prevents any one company from serving every needed role. Because so many organizations have to be involved in providing a new technology, many new technologies end up failing.

The lesson is that understanding how a new communication technology makes it to market requires comparatively little understanding of the technology itself compared with the understanding needed of the industry in general, especially the distribution processes.

A “Blue” Lesson

One of the best examples of the need to understand (and perhaps exploit) all of the paths illustrated in Figure 4.1 comes from the earliest days of the personal computer. When the PC was invented in the 1970s, most manufacturers used their own operating systems, so that applications and content could not easily be transferred from one type of computer to other types. Many of these manufacturers realized that they needed to find a standard operating system that would allow the same programs and content to be used on computers from different manufacturers, and they agreed on an operating system called CP/M.

Before CP/M could become a standard, however, IBM, the largest U.S. computer manufacturer—mainframe computers, that is—decided to enter the personal computer market. “Big Blue,” as IBM was known (for its blue logo and its dominance in mainframe computers, typewriters, and other business equipment) determined that its core competency was making hardware, and they looked for a company to provide them an operating system that would work on their computers. They chose a then-little-known operating system called MS-DOS, from a small startup company called Microsoft.

IBM’s open architecture allowed other companies to make compatible computers, and dozens of companies entered the market to compete with Big Blue. For a time, IBM dominated the personal computer market, but, over time, competitors steadily made inroads on the market. (Ultimately, IBM sold its personal computer manufacturing business in 2006 to Lenovo, a Chinese company.)

The one thing that most of these competitors had in common was that they used Microsoft’s operating systems. Microsoft grew… and grew… and grew. (It is also interesting to note that, although Microsoft has dominated the market for software with its operating systems and productivity software such as Office, it has been a consistent failure in most areas of hardware manufacturing. Notable failures include its routers and home networking hardware, keyboards and mice, and WebTV hardware. The only major success Microsoft has had in manufacturing hardware is with its Xbox video game system, discussed in Chapter 15.)

The lesson is that there is opportunity in all areas of production and distribution of communication technologies. All aspects of production and distribution must be studied in order to understand communication technologies. Companies have to know their own core competencies, but a company can often improve its ability to introduce a new technology by controlling more than one function in the adoption path.

What are the Industries?

We need to begin our study of communication technologies by defining the industries involved in providing communication-related services in one form or another. Broadly speaking, these can be divided into:

These industries were introduced in Chapter 2 and are discussed in more detail in the individual chapters that follow.

At one point, these industries were distinct, with companies focusing on one or two industries. The opportunity provided by digital media and convergence enables companies to operate in numerous industries, and many companies are looking for synergies across industries.

Table 4.1

Examples of Major Communication Company Industries, 2018

The number of dots is proportional to the importance of this business to each company.

Source: A. Grant (2018)

Table 4.1 lists examples of well-known companies in the communication industries, some of which work across many industries, and some of which are (as of this writing) focused on a single industry. Part of the fun in reading this chart is seeing how much has changed since the book was printed in mid-2018.

There is a risk in discussing specific organizations in a book such as this one; in the time between when the book is written and when it is published, there are certain to be changes in the organizational structure of the industries. For example, as this chapter was being written in early 2018, Netflix and DirecTV were distributing UltraHD television through online services. By the time you read this, some broadcasters are sure to have adopted a set of technical standards known as ATSC 3.0, allowing them to deliver UltraHD signals directly to viewers.

Fortunately, mergers and takeovers that revolutionize an industry do not happen that often—only a couple a year! The major players are more likely to acquire other companies than to be acquired, so it is fairly safe (but not completely safe) to identify the major players and then analyze the industries in which they are doing business.

As in the AT&T story earlier in this chapter, the specific businesses a company is in can change dramatically over the course of a few years.

Future Trends

The focus of this book is on changing technologies. It should be clear that some of the most important changes to track are changes in the organizational structure of media industries. The remainder of this chapter projects organizational trends to watch to help you predict the trajectory of existing and future technologies.

Disappearing Newspapers

For decades, newspapers were the dominant mass medium, commanding revenues, consumer attention, and significant political and economic power. Since the dramatic drop in newspaper revenues and subscriptions began in 2005, newspaper publishers have been reconsidering their core business. Some prognosticators have even predicted the demise of the printed newspaper completely, forcing newspaper companies to plan for digital distribution of their news and advertisements.

Before starting the countdown clock, it is necessary to define what we mean by a “newspaper publisher.” If a newspaper publisher is defined as an organization that communicates and obtains revenue by smearing ink on dead trees, then we can easily predict a steady decline in that business. If, however, a newspaper publisher is defined as an organization that gathers news and advertising messages, distributing them via a wide range of available media, then newspaper publishers should be quite healthy through the century.

The current problem is that there is no comparable revenue model for delivery of news and advertising through new media that approaches the revenues available from smearing ink on dead trees. It is a bad news/good news situation.

The bad news is that traditional newspaper readership and revenues are both declining. Readership is suffering because of competition from the Web and other new media, with younger cohorts increasingly ignoring print in favor of other sources.

Advertising revenues are suffering for two reasons. The decline in readership and competition from new media are impacting revenues from display advertising. More significant is the loss in revenues from classified advertising, which at one point comprised up to one-third of newspaper revenues.

The good news is that newspapers remain profitable, at least on a cash flow basis, with gross margins of 10% to 20%. This profit margin is one that many industries would envy. But many newspaper companies borrowed extensively to expand their reach, with interest payments often exceeding these gross profits. Stockholders in newspaper publishers have been used to much higher profit margins, and the stock prices of newspaper companies have been punished for the decline in profits.

Some companies reacted by divesting themselves of their newspapers in favor of TV and new media investments. Some newspaper publishers used the opportunity to buy up other newspapers; consider McClatchy’s 2006 purchase of the majority of Knight-Ridder’s newspapers (McClatchy, 2008) or the Digital First Media purchase of Freedom Communications, Inc. in 2016 (Gleason, 2016).

Advertiser-Supported Media

For advertiser-supported media organizations, the primary concern is the impact of the Internet and other new media on revenues. As discussed above, some of the loss in revenues is due to loss of advertising dollars (including classified advertising), but that loss is not experienced equally by all advertiser-supported media.

The Internet is especially attractive to advertisers because online advertising systems have the most comprehensive reporting of any advertising medium. For example, advertisers using Google AdWords (discussed in Chapter 1) gets comprehensive reports on the effectiveness of every message—but “effectiveness” is defined by these advertisers as an immediate response such as a click-through.

As Grant & Wilkinson (2007) discuss, not all advertising is “call-to-action” advertising. There is another type of equally important advertising—image advertising, which does not demand immediate results, but rather works over time to build brand identity, increasing the likelihood of a purchase.

Any medium can carry any type of advertising, but image advertising is more common on television (especially national television) and magazines, and call-to-action advertising is more common in newspapers. As a result, newspapers, at least in the short term, are more likely to be impacted by the increase in Internet advertising.

Interestingly, local advertising is more likely to be call-to-action advertising, but local advertisers have been slower than national advertisers to move to the Internet, most likely because of the global reach of the Internet. This paradox could be seen as an opportunity for an entrepreneur wishing to earn a million or two by exploiting a new advertising market (Wilkinson, Grant & Fisher, 2012).

The “Mobile Revolution”

Another trend that can help you analyze media organizations is the shift toward mobile communication technologies. Companies that are positioned to produce and distribute content and technology that further enable the “mobile revolution” are likely to have increased prospects for growth.

Areas to watch include mobile Internet access (involving new hardware and software, provided by a mixture of existing and new organizations), mobile advertising, new applications of GPS technology, and new applications designed to take advantage of Internet access available anytime, anywhere.

Consumers—Time Spent Using Media

Another piece of good news for media organizations is the fact that the amount of time consumers are spending with media is increasing, with much of that increase coming from simultaneous media use (Papper, et al., 2009). Advertiser-supported media thus have more “audience” to sell, and subscription-based media have more prospects for revenue.

Furthermore, new technologies are increasingly targeting specific messages at specific consumers, increasing the efficiency of message delivery for advertisers and potentially reducing the clutter of irrelevant advertising for consumers. Already, advertising services such as Google’s Double-Click and Google’s Ad-Words provide ads that are targeted to a specific person or the specific content on a Web page, greatly increasing their effectiveness.

Imagine a future where every commercial on TV that you see is targeted—and is interesting—to you! Technically, it is possible, but the lessons of previous technologies suggest that the road to customized advertising will be a meandering one.

Principle of Relative Constancy

The potential revenue from consumers is limited because they devote a fixed proportion of their disposable income to media, the phenomenon discussed in Chapter 3 as the “Principle of Relative Constancy.” The implication is emerging companies and technologies have to wrest market share and revenue from established companies. To do that, they can’t be just as good as the incumbents. Rather, they have to be faster, smaller, less expensive, or in some way better so that consumers will have the motivation to shift spending from existing media.

Conclusions

The structure of the media system may be the most dynamic area in the study of new communication technologies, with new industries and organizations constantly emerging and merging. In the following chapters, organizational developments are therefore given significant attention. Be warned, however; between the time these chapters are written and published, there is likely to be some change in the organizational structure of each technology discussed. To keep up with these developments, visit the Communication Technology Update and Fundamentals home page at www.tfi.com/ctu.

Bibliography

AT&T. (2008). Milestones in AT&T history. Retrieved from http://www.corp.att.com/history/milestones.html.

Dizard, W. (1989). The coming information age: An overview of technology, economics, and politics, 2nd ed. New York: Longman.

Gleason, S. (2016, April 1). Digital First closes purchase of Orange County Register publisher. Wall Stree Journal. Online: http://www.wsj.com/articles/digital-first-closes-purchase-of-orange-county-register-publisher-1459532486

Grant, A. E. (1990, April). The “pre-diffusion of HDTV: Organizational factors and the “diffusion threshold. Paper presented to the Annual Convention of the Broadcast Education Association, Atlanta.

Grant, A. E. & Wilkinson, J. S. (2007, February). Lessons for communication technologies from Web advertising. Paper presented to the Mid-Winter Conference of the Association of Educators in Journalism and Mass Communication, Reno.

Hush-A-Phone Corp. v. AT&T, et al. (1955). FCC Docket No. 9189. Decision and order (1955). 20 FCC 391.

Hush-A-Phone Corp. v. United States. (1956). 238 F. 2d 266 (D.C. Cir.). Decision and order on remand (1957). 22 FCC 112.

Kottler, P. & Keller, K. L. (2005). Marketing management, 12th ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

McClatchy. (2008). About the McClatchy Company. Retrieved from http://www.mcclatchy.com/100/story/179.html.

Microwave Communications, Inc. (1969). FCC Docket No. 16509. Decision, 18 FCC 2d 953.

Papper, R. E., Holmes, M. A. & Popovich, M. N. (2009). Middletown media studies II: Observing consumer interactions with media. In A. E. Grant & J. S. Wilkinson (Eds.) Understanding media convergence: The state of the field. New York: Oxford.

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations, 5th ed. New York: Free Press.

Wilkinson, J.S., Grant, A. E. & Fisher, D. J. (2012). Principles of convergent journalism (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

_______________

* J. Rion Mckissick Professor of Journalism, School of Journalism and Mass Communications, University of South Carolina (Columbia, South Carolina).