20

Ebooks

Overview

Ebooks are a group of technologies that allow the distribution of traditionally printed material to computers and handheld devices. Ebooks offer the opportun ity to disrupt traditional publish ing through inexpens ive distribut ion and the opportunity for new voices. Groups like Project Gutenberg have transferred the great works and documents to electronic form for inexpensive distribution. Independent authors now have the potential to circumvent the traditional big publishers to reach an audience. Interactive technology allows new opportunities from simple audio versions of the books, text-to-speech, interactive stories, and expansion into multimedia content.

This technology that was supposed to disrupt the publishing industry has, itself, been disrupted by new marketing techniques and options. Amazon, the market leader in electronic paper, now has been accused anti-competitive activity as it revamps the way it distributes ebooks to its powerful Prime services and competitors work to answer the challenge. The question is if the new marketplace will be good for independent authors and the wider audience.

Introduction

The idea of distributing books in digital form is as old the computer communication itself. Even with slower transmission speeds, book-length files could be distributed without unnecessary delay or cost. The goal was to free the publishing industry from paper while expanding the audience of books. While ebooks have become an important part of the publishing industry, adoption of ebooks has fallen far short of expectation amid competing formats, devices, and business models.

This book is available in both electronic and paper formats. Why did you choose the format you are reading? Some like the mobility of carrying several books without adding weight, the ability to acquire a book quickly, or rent a book without worrying about physically returning it. Some prefer the feel of paper in their hands, the “under the tree” experience of reading anywhere they want and avoiding having to learn the software or buy new hardware. Others want to disconnect from technology while reading or find a format easier to share. Does book content affect your choice? For example, would a Bible or another religious book feel the same in electronic form? How does price affect your choice? The relationship that people have with the technology affects the market for ebooks. That relationship may and in some ways has changed. This chapter will examine the factors that have changed ebooks over the years.

Background

Ebooks require the combination of content, software, hardware, and organizational infrastructure. Also, the level of interactivity or computer-aided intelligence has varied by the system. There has been no consistent solution; individuals and organizations have promoted models for each.

Content

The content was the first necessary component. In 1971, University of Illinois student Michael Hart enjoyed access to ARPANET computers (the predecessor to the Internet). He used his access to type in and distribute the Declaration of Independence followed by Bill of Rights, American Constitution, and the Christian Bible (The Guardian, 2002). The effort continues today as Project Gutenberg currently offers more than 56,000 free ebooks (www.Gutenberg.org). Project Gutenberg and other non-profit organizations worked to digitize public domain text either through labor-intensive typing or scanning into computer formats. Later, some authors began to release work through creative commons or without copyright rather than market through the normal publication process.

These publicly available books became the backbone content to distribute ebooks, but soon more commercial products entered the field. Three main companies, Ereader, Bibliobytes, and Fictionworks began the sale of ebooks in the 1990’s (The Telegraph, 2018). Google created its book search engine in 1994 (later Google books), and by this time, the effort to convince authors to distribute content in electronic form came in full force. Also, the public domain books were enhanced with better formatting, annotation, or illustrations to produce work sold for a low, but profitable rate. Independent authors, wishing to become professional were the first to offer content. In 2007, Amazon joined the ebook market when it introduced its Kindle ereader (discussed later) and started to sell content from major authors. Amazon was followed by Barnes & Noble, Apple, and Google (among others) and the potential seemed clear enough that major publishers would offer their books to electronic sales. In 2011, Amazon announced that ebooks began to outsell traditional books (Miller & Bossman, 2011).

Software

Effective ebook distribution requires two types of software—file formats and display. Over the years, there have been multiple versions of each. Some people may not consider file formats software because the intention is to provide content rather than instructions to the hardware. However, most file formats contain markers for several aspects of the ebook experience. Display software can provide simple information like chapter markers, page turn locations , display of images, and interaction with dictionaries. File formats evolved from text storage (ASCII or American Standard Code for Information Interchange) and word processing formats (Adobe PDF). Many of the early abandoned formats (like LIT and MOBI) are still available in online ebook resources so you can still use them on your devices.

Display software evolved as ebook distributors needed to enforce licensing through Digital Rights Management (DRM), and users wanted a better reading experience. DRM enforces the book licenses, including approved reader accounts, time and geographic restrictions, and allowable devices. Other aspects of the display system may allow interactivity (discussed below) and help manage files. Thus, a reader may be allowed to share or lend a book, enforce time restrictions, or move a book from one company’s hardware to another.

As ebooks have moved from dedicated hardware ereaders to other devices, the software has become more important and complex. The software for computer, web, smartphones, and tablets had to provide the same experience as the dedicated ereader as well as the ability to manage files across devices. Screen quality, colors, and processing power allow the image quality needed for graphic novels and comic books, Adobe PDF documents, audiobooks, and interactive books for children and multimedia.

Table 20.11:

Ereader File Formats

Format |

Creator |

Introduced |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

ASCII |

American National Standards Institute |

1963 |

Many have built on this standard to add additional capability such as “rich text.” |

ePub |

International D igital Publishing Forum |

2007 |

Widely used by Google, Android, and Apple. An open format but modified by some |

AZW |

Amazon |

2007 |

DRM added to MOBI for Amazon Kindle. Replaced by KF8. |

LIT |

Microsoft |

2000 |

Microsoft discontinued support in 2012 |

ODF |

OASIS and OpenOffice |

2005 |

Used in many alternatives to Microsoft Office. XML |

MOBI |

Mobipocket |

2000 |

Altered original Palm format then purchased by Amazon. |

Adobe |

1993 |

Designed for page layout. |

Source: S. Dick

Comic book and graphic novel ebooks demand high-resolution images. Online origins came more from HTML (web) coding than text formats. Merging the DRM demanded by publishers with the high-quality graphics, and the need to display a logical progression of images rather than text, was not easy. These graphic format books were not possible in classic ereaders and demanded software for tablets, smartphones, computer, and web interfaces (Wilson, 2015).

Before the widespread use of smaller, lighter hardware such as tablets, notebook computers, and smartphones, PDF documents required too much memory and did not format well for smaller screens. Some smartphone software such as Foxit, allowed readers to take the text out of PDFs and “reflow” it for easier reading on the small screens. Breakthroughs came with larger touch-screen PDF software allowing readers to annotate the document on the fly by writing (pen or finger) or typing directly to the document as if it were on paper. It makes PDF documents truly feel like electronic paper—a major goal of ebooks and a popular feature for businesses as people can edit and sign documents with all the formatting of a finished commercial product.

In 1932, the tests of audio recorded books included a chapter from Hellen Keller’s book Mainstream and Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven (Audio Publishers Association, n.d.). These “Talking Books” from the Library of Congress were intended for the blind. The start was slow but got a push with the intraduction of the audio cassette tape in 1963 and books on tape increased popularity in the 1970s and 1980s. The company, Audible created a practical digital audio player in 1997 and joined Apple’s iTunes library in 2003. In 2008, digital downloads began to surpass CD audiobooks. Audiobook software is both dependent on the intelligence of computer technology and carefully crafted to provide the same experience across platforms, so the iOS version and the Android version looks and operates similarly.

Interactivity

In 1987, two systems introduced interactivity to reading. Eastgate systems introduced Afternoon, a hypertext fiction by Michael Joyce (The Guardian, 2002). Apple introduced Hypercard, an interactive software package that could allow authors to create an interactive storyline with multiple branches, enabling readers to jump from point to point in a text. Hypercard could be used for presentations, reference works, or learning tools that allowed the reader to choose topic areas (Kahney, 2002). These early interactivity experiments transitioned to content written in HTML and other web formats. Now, the content often transitions to interactive storybook apps.

Display software has begun to allow readers to communicate across devices. Interactivity across devices allow a reader to move from device to device and continue reading at the same point including a seamless flow between text and audiobooks. Interactivity can extend across readers as well including shared personal notes, highlights, and social media posts. Religious books such as Bibles supplied by Olive Tree allow users to compare passages across translations, immediately find commentary, maps, dictionaries and other study aids. Dedicated apps like WebMD and cookbooks like Tasty could be considered interactive ebooks.

Children books are attracting the most aggressive software investment for interactive texts. Children’s ebooks require the display capability of graphic novels, sound from audiobooks, and interactive or branching capability from HTML. One app called Novel Effects reaches across formats by using voice recognition to “hear” a parent reading a traditional book to a child and adding sound effects.

Hardware

In some cases, ebooks have been simply a companion product or feature to a technology. In others, ebooks are the killer app or primary reason to buy a product. The first handheld devices for ebooks were a flurry of personal digital assistants (PDA). As a precursor to the modern smartphone, these devices were meant to be used to store appointment, contacts, and other data. But optional apps became available. Apple entered first in 1993 with it short-lived Newton followed by Palm Pilot in 1996 and the Microsoft Reader in 2000. The handheld devices allowed the user to both read material and write on something about the size of the modern smartphone.

The most visible ebook hardware is the ereader with E-Ink. E-Ink is a form of electronic paper (Primozic, 2015) that was featured with the Kindle in 2007 (Wagner, 2011). The black and white screens on Kindles mimic paper’s reflective property. Since they reflect light rather than produce it (the way a television or computer screen does), the ereader can operate with much longer battery life. E-Ink uses pixels (picture elements) made up of the clear solution with negatively charged dark particles and positively charged white particles. When a positive charge is placed on the top of the pixel, the negatively charged dark particles are attracted to it, and the pixel goes dark. The opposite is true with the white particles. Later, grey pixels were possible by manipulating the charge (see Figure 20.1).

Consumers’ desire for color images and capabilities beyond ereaders were answered by a group of tablet devices often built on Google’s Android operating system and Apple’s iOS. Today, the smartphone and the tablet are quickly becoming the most popular hardware readers for ebooks (Haines, 2018).

Pixel Construction with E-ink

Source: S. Dick

Organizational Infrastructure

The assumed disruptive influence of ebooks on the traditional distribution model of the industry caused publishers and distributors to change their marketing plans. The problems went beyond DRM. The first choice was to license the books rather than sell them—an important change from print. Print books are sold, and the physical book then belongs to the buyer—other than the copyright. In the U.S., the buyer can do whatever they want with that one copy under what is called the “First Sale Doctrine” (Department of Justice, n.d.). That includes selling, lending, or giving away the book. The publisher only makes money on the first sale. Licensing changes that relationship. Instead of buying the book, you are buying the right to read that book. Many current licenses allow you to “lend” or “give” it to another person but they also only get a license to read it. Licensing a book rather than selling it allows publishers to profit from more sales.

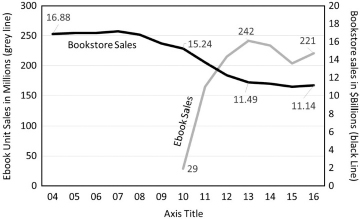

Ebook Sales in Billions of US Dollars by Year

Source: Statista

The relationship between the new ebooks and traditional publishing was essential to the new marketing plans. By culling data from US Census Bureau and publishing industry reports, Statista (2017) provides enough information to understand the relationship between bookstore sales and ebook sales (see Figure 20.2) Amazon’s Kindle was introduced in 2007 and bookstore sales (including items other than books) began to drop. Between 2010 and 2013, ebook sales exploded from 29 to 242 million books while bookstore sales dropped by nearly $4 billion. There had to be discussion as to how to distribute ebooks without killing bookstores.

The ereader, specifically the Amazon Kindle, was designed for impulse purchases. While the first ereaders were connected to a computer by wire, later devices quickly adopted wireless technology—at first cell and later Wi-Fi (Pierce, 2017). The goal was to create a device that would allow a user to hear about a new title and buy it immediately. The combination of a single lightweight device that would hold many books, no need to go to the store, and the excitement of the latest technology was undeniable. The expectation was that the disruptive influence of electronic distribution was going to come to publishing, and eventually most books would be replaced by ebooks.

However, more was happening than a simple technological change. Not only were ebooks replacing traditional books but also physical bookstores were being replaced by online bookstores. Pricing was also affected as Amazon pushed for a simple standard of $9.99 for most major books. Apple was already using flat rate pricing for music sales. It seemed natural to settle on the single price. The goal was to create a system where the customer would not put much thought into the order (Pierce, 2017). Major publishers, unhappy with the payment structure forced reconsideration of the flat rate price.

Libraries face a special challenge when distributing ebooks (Meadows, 2017). Publishers, fearing revenue loss to ebooks, have been far more restrictive to libraries. Realistically, the experience is very different. To borrow a paper book from the library takes two trips to the physical location, and the book may be in poor condition (The Authors Guild, 2018). Ebooks can be borrowed online and are always in original condition. The software for online libraries can automatically “return” books, so the online library and online bookstore are nearly identical experiences other than the time of ownership (access). Publishers also worry about the security of the soft-ware—possibly allowing borrowers to obtain ebooks free of digital rights management (Meadows, 2017).

Specific online interfaces manage the borrowing processes for libraries such as OverDrive that serve many libraries and provides a dedicated ereader software for local libraries. National libraries have developed such as Project Gutenberg (https://www.gu-tenberg.org/), and The Internet Archive’s Openlibrary (https://openlibrary.org/). The OpenLibrary buys paper copies of books and acquires or creates digital copies of books. The library then loans electronic copies to match paper books it holds. This interpretation of the Fair Use Doctrine exception to Copyright Law is currently a source of dispute between the OpenLibrary, publishers, and the Authors Guild (Meadows, 2017). The outcome of this dispute will determine the rights for online libraries in the future. Google Books (not Google’s Play Store) is a hybrid model allowing users to search the contents of books. If the user finds a book she wants to read, she will be linked to locations where she can buy (Play Store) or borrow books—depending on availability.

Recent Developments

Book publishers earn about $7 billion a year (Statista, 2017) not including retail markup. Market share for ebooks has begun to fall from a high of 26% in 2014 and down to 17% in 2017 according to an industry trade group (American Association of Publishers, n.d.). The one exception was a dramatic growth in audio-books with market share growing from 3% in 2014 to 5.6% in 2017.

Some point to the devices (Milliot, 2016) as the cause of sales decline. These people believe that ereaders are not attractive to consumers—especially among young people. Ereaders, tablets, and smart-phones represent work, and people are using reading as an opportunity to disconnect. Handheld electronics are expensive and in the case of ereaders, only useful for one purpose. Even the simplest ereader can cost between $50 and $200. It might be better to pay for the books you are actually going to read than pay for the ereader plus the books.

Market Share by Publishing Product

Source: S. Dick

Certain categories of books remain popular for paper publishing. The latest fad of adult coloring books, children’s, and hardback books lead the categories that sell better in paper (Sweney, 2016). People seem to have a natural affinity for relaxing with paper rather than electronic ink.

Cheap and easy book rentals, professor published material, and the ease of carrying several electronic books across campus caused several universities to create initiatives to transfer from paper to electronic book formats (Redden, 2009). With textbooks, some books are sold in both formats to read one at home and carry the other to the classroom.

It is also possible that sales numbers do not accurately reflect ebook sales. Interactive books and games for children, medical texts, and religious publications may not calculate into publishing sales figures and can quickly cross a line that would cut them out of the traditional publishing sales figures. For example, Book publisher Olive Tree publishes bibles and bible study products outside normal publishing channels. Chu Chu TV (www.youtube.com/user/TheChuChutv) is a YouTube Channel and app. It rewrites traditional children’s stories and nursery rhymes. Finally, the original Grey’s Anatomy has been repackaged in the app Visual Anatomy. Absent interactive technology, these interactive applications might be produced by the publishing industry, and it is doubtful that most are included in the ebook sales figures.

New pricing models affect ebook sales calculations. First, as major publishers have entered the market, calculations are not as accurate for independent publishers and writers concentrating instead on the best-selling books. Second, free or promotional books are easy to distribute (Trachtenberg, 2010). Rather than selling your title outright, give away a book in exchange for reputation or corporate promotion (Anderson, 2009). Finally, in July 2014, Amazon introduced Kindle Unlimited—a substantial collection of ebooks available at no additional cost to subscribers of their Prime service. Instead of buying or renting a single book, the pricing is changed to a subscription model for a library of titles and authors are paid a share of subscriptions instead of a per-book royalty. Both Barnes & Noble and Kobo have started subscription services as well. Because all these changes, the systems that count book sales may be undercounting in a changing marketplace (Pierce, 2017).

Current Status

According to the American Association of Publishers (2018), October 2017 sales for the publishing industry were very strong resulting in a year to date increase of 1.7% over 2016. Unfortunately, ebook sales dropped by 5.5%. The one category that showed real gains was audiobooks, with sales up 27.9% compared to the previous year. The moderating effect may be in part due to ebooks becoming more expensive as large publishing houses force ebook price increases to more closely match the prices of traditional books.

Pricing inconsistency is becoming an issue. While Amazon has tried to enforce sales contracts with authors that give them the best possible price. There are two basic models for setting the price. In the wholesale model, the publisher or author suggests a price but sells the book to the distributor at a much lower wholesale price. The distributor is then free to set whatever price it wishes to put on the book. So, the price to the distributor may $6.99 with a suggested price of $12.99, but the distributor may choose to sell the book for $9.99. This makes it more difficult for the publisher to sell the book at equal prices across sales channels.

The agency price model gives more control to the publisher—so it is favored by the larger publishing houses. With agency pricing, the publisher sets the price on the book, and the distributor receives a commission on each sale. Here, the publisher sets the price for $12.99 and gives the distributor 40% on each book sold. This model does not work well with Amazon desire to standardize prices and runs sales. Overall, it also has the effect of pushing the prices higher—more equal to printed books. Agency pricing has been blamed for raising the price of ebooks and contributing to the slump in ebook sales (Miller & Bosman, 2011).

In the first quarter of 2017 (one of the lowest earners because it comes after Christmas), book publishers earned $2.33 billion—a 4.9% increase over the same quarter of 2016. For the same period, downloaded audio grew 28.8%, and hardback books grew by 8.25. Paperback book sales dropped by 4.7%, and ebooks sales dropped by 5.3%. A check of Google, Amazon, and Apple app stores revealed 4.55 million downloads of ebook reader apps. Apple’s iBooks is unavailable because it is preloaded and not available in any app store. Top remaining apps were split between Kindle (26%), Google (31%), and Audible (31%). Kobo only represented 7% of all downloads and Overdrive (for libraries) had only 6%. Traditional ereaders like the Kindle and Nook are quickly losing market share (Haines, 2018). Shipment of ereaders dropped to 7.1 million units in 2016, down from 23.2 million in 2011. The drop in sales of ereaders reflects the fact that more people are reading on smartphones and newer lighter tablets.

Downloads of Ereader Apps by Percent

Source: S. Dick

Factors to Watch

It is impossible to effectively evaluate the ebook industry without considering the effect of Amazon. This one company can set prices and terms, as it dominates the market with an estimated 75% of the revenue. Because of their position, Amazon can be said to enjoy “monopsony power”—a situation where there is one effective buyer to a class of goods (London, 2014). Many authors feel they must sell to Amazon if their book is to be successful.

One of the most problematic demands is Amazon’s “most favored nation” (MFN) clause. The MFN requires publishers doing business with Amazon to reveal the terms of the contracts made with its competitors. Amazon would then be in a position to demand equal or better terms. By marshaling MFN power over writers, they have been able to require significant concessions that reduce their costs and move them closer to monopoly (one effective seller) status including cost sharing, promotion, and release date. The European Community agreed with Amazon to end MFN in exchange for the end of a three-year antitrust investigation (Vincent, 2017).

The continuing problems of the biggest tech companies—especially Amazon with its success across product lines—have moved many to suggest anti-trust investigations in the United States (Ip, 2018). Even if Amazon can avoid litigation as it did in Europe, there are other possibilities. The activities of the major ebook retailers (Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Apple, and Google) or the big five publishers (Holtzbrinck Publishing Group/Macmillan, Hachette, HarperCollins, Random House, and Simon & Schuster) could be seen as an oligopolistic (undesirably few sellers). Oligopolies can lead to collusive behavior that ultimately hurts the consumer.

Getting a Job

Despite the challenges, the ebook market has grown to the point that independent publishers can market a book without excessive costs. In 2016, there were 787,000 self-published books in both print and ebook format (Statista, n.d.) You no longer have to sell your book to the major publishers, but you do need to compete with them. If you are going to publish on your own, you will have to handle some of the overhead duties (promotion, financial management, editing, design, and more) yourself. Also, you must negotiate your own deal to distribute the book. For most, that means dealing with Amazon. On Amazon, you have the choice of acting as an independent publisher or as a part of the Amazon imprint. Your choices will affect your relationship or even availability to work with other ebook distributors.

Bibliography

American Associaion of Publishers. (2018, February 28). Book Publishers Revenues up 27.6% in October 2017. American Association of Publishers: Retrieved from http://Newsroom.publishers.org/media-library.

American Association of Publishers. (n.d.). Media for Download. American Association of Publishers: Retrieved from http://newsroom.publishers.org/media-library.

Anderson, C. (2009). FREE: The Future of a Radical Price. New York: Hyperion.

Audio Publishers Association. (n.d.). A History of AudioBooks. Audio Pubishers Association:Retrieved from https://www.audiopub.org/uploads/images/backgrounds/A-history-of-audiobooks.pdf.

Department of Justice. (n.d.). Criminal Resource Manual. Department of Justice: Retrieved from https://www.justice.gov/usam/criminal-resource-manual-1854-copyright-infringement-first-sale-doctrine.

Haines, D. (2018, Feb 25). The Ereader Device is Dying a Rapid Death. Just Publishing Advice: Retrieved from https://justpublishingadvice.com/the-e-reader-device-is-dying-a-rapid-death/.

Ip, G. (2018, January 16). The Antitrust Case Against Facebook, Google, and Amazon. Wall Street Journal: Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-antitrust-case-against-facebook-google-amazon-and-apple-1516121561.

Kahney, L. (2002, Aug 14). Hypercard Forgotten But Not Gone. Wired: Retrieved from https://www.wired.com/2002/08/hypercard-forgotten-but-not-gone/.

London, R. (2014, October 20). Big, bad Amazon. The Economist: Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/blogs/freeexchange/2014/10/market-power.

Meadows, C. (2017, Dec 19). The Internet Archive’s OpenLibrary Project Violates Copyright, the Authors Guild Warns. TeleRead: Retrieved from https://teleread.org/2017/12/19/the-internet-archives-openlibrary-project-violates-copyright-the-authors-guild-warns/.

Miller, C. C., & Bosman, J. (2011, May 19). Ebooks Outsell Print Books at Amazon. New York Times: Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/20/technology/20amazon.html.

Milliot, J. (2016, June 17). As E-book Sales Decline, Digital Fatigue Grows. Publishers Weekly: Retrieved from https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/digital/retailing/article/70696-as-e-book-sales-decline-digital-fatigue-grows.html.

Pierce, D. (2017, December 20). The Kindle changed the Book Business. Can it change books? Wired: Retrieved from https://www.wired.com/story/can-amazon-change-books/.

Primozic, U. (2015, March 5). Electronic Paper Explained. Visionect: Retrieved from https://www.visionect.com/blog/electronic-paper-explained-what-is-it-and-how-does-it-work/.

Redden, E. (2009, January 14). Toward and All E-Book Campus. Inside Higher Ed: Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2009/01/14/ebooks.

Statista. (2017, March). Book store sales in the United States from 1992 to 2015 (in billion U.S. dollars). Statista: Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/197710/annual-book-store-sales-in-the-us-since-1992/.

Statista. (n.d.). Ebooks. Statista: Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/249036/number-of-self-published-books-in-the-us-by-format/.

Suich, A. (n.d..). From Papyrus to Pixels. Economist Essay: Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/news/essays/21623373-which-something-old-and-powerful-encountered-vault.

Sweney, M. (2016, May 13). Printed Book Sales Rise for the First Time in Four Years as Ebook Sales Decline. The Guardian: Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/media/2016/may/13/printed-book-sales-ebooks-decline.

The Authors Guild. (2018, January 18). An Update on Open Library. Industry & Advocacy News: Retrieved from https://www.authorsguild.org/industry-advocacy/update-open-library/.

The Guardian. (2002, Jan 3). Ebooks Timeline. The Guardian: Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/books/2002/jan/03/ebooks.technology.

The Telegraph. (2018, February 17). Google Editions: a history of ebooks. The Telegraph: Retrieved from http://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/google/8176510/Google-Editions-a-history-of-ebooks.html.

Trachtenberg, J. A. (2010, May 21). E-Books Rewrite Bookselling. Wall Street Journal: Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748704448304575196172206855634.

Vincent, J. (2017, May 4). Amazon Will Change Its Ebook Contracts with Publishers as EU ends Antitrust Probe. The Verge: Retrieved from https://www.theverge.com/2017/5/4/15541810/eu-amazon-ebooks-antitrust-investigation-ended

Wagner, K. (2011, Sept 28). The History of the Amazon Kindle So Far. Gizmodo: Retrieved from https://gizmodo.com/5844662/the-history-of-amazons-kindle-so-far/.

Wilson, J. L. (2015, March 25). Everything You Need to Know About Digital Comics. PC Magazine: Retrieved from https://www.pcmag.com/article2/0,2817,2425402,00.asp.

_______________

* Senior Research Scientist, Communications Department, University of Louisiana at Lafayette, Lafayette, Louisiana