Chapter 4. Infrastructure

Topics in This Chapter

• 4.1 Encapsulate Game Functions in a JavaScript Object

• 4.2 Understand JavaScript’s Persnickety this Reference

• 4.4 Pause or Resume the Game When the Player Presses the p Key

• 4.5 Freeze the Game to Ensure It Resumes Exactly Where It Left Off

• 4.6 Pause the Game When the Window Loses Focus

• 4.7 Resume a Paused Game with an Animated Countdown

Many aspects of game programming have nothing to do with gameplay. Displaying instructions, pausing games, transitioning between levels, and displaying game credits are just some features that game developers implement besides gameplay. Those features, however, contribute a great deal to the overall impression your game makes on players, so it’s important to implement them well and add some polish.

In the last chapter, we discussed graphics and animation, which are fundamental to Snail Bait’s gameplay. In this chapter, we implement some of the game’s infrastructure, starting by encapsulating Snail Bait’s code in a JavaScript object.

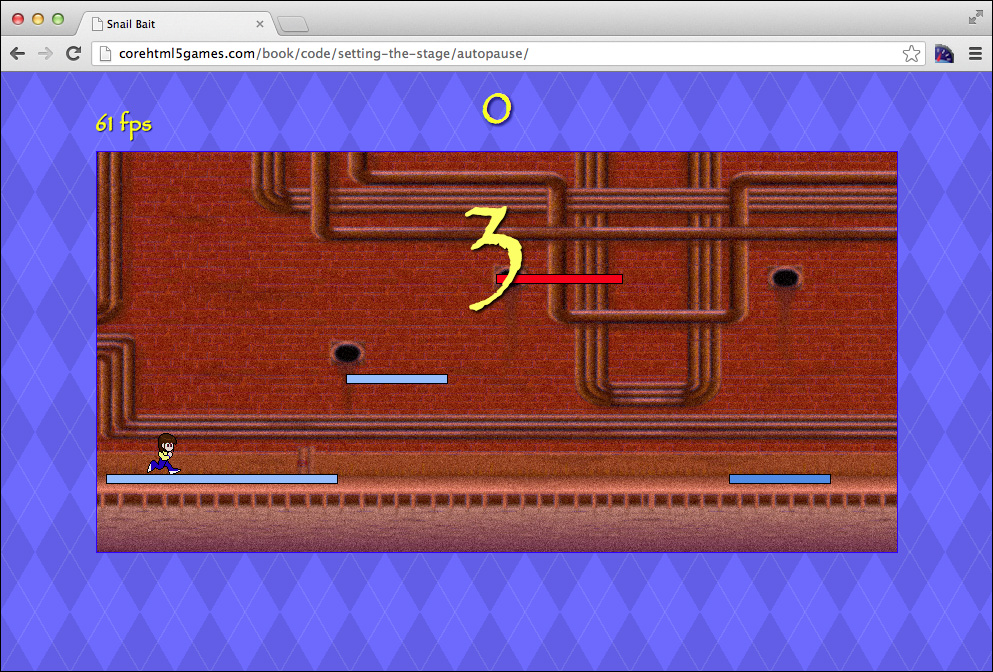

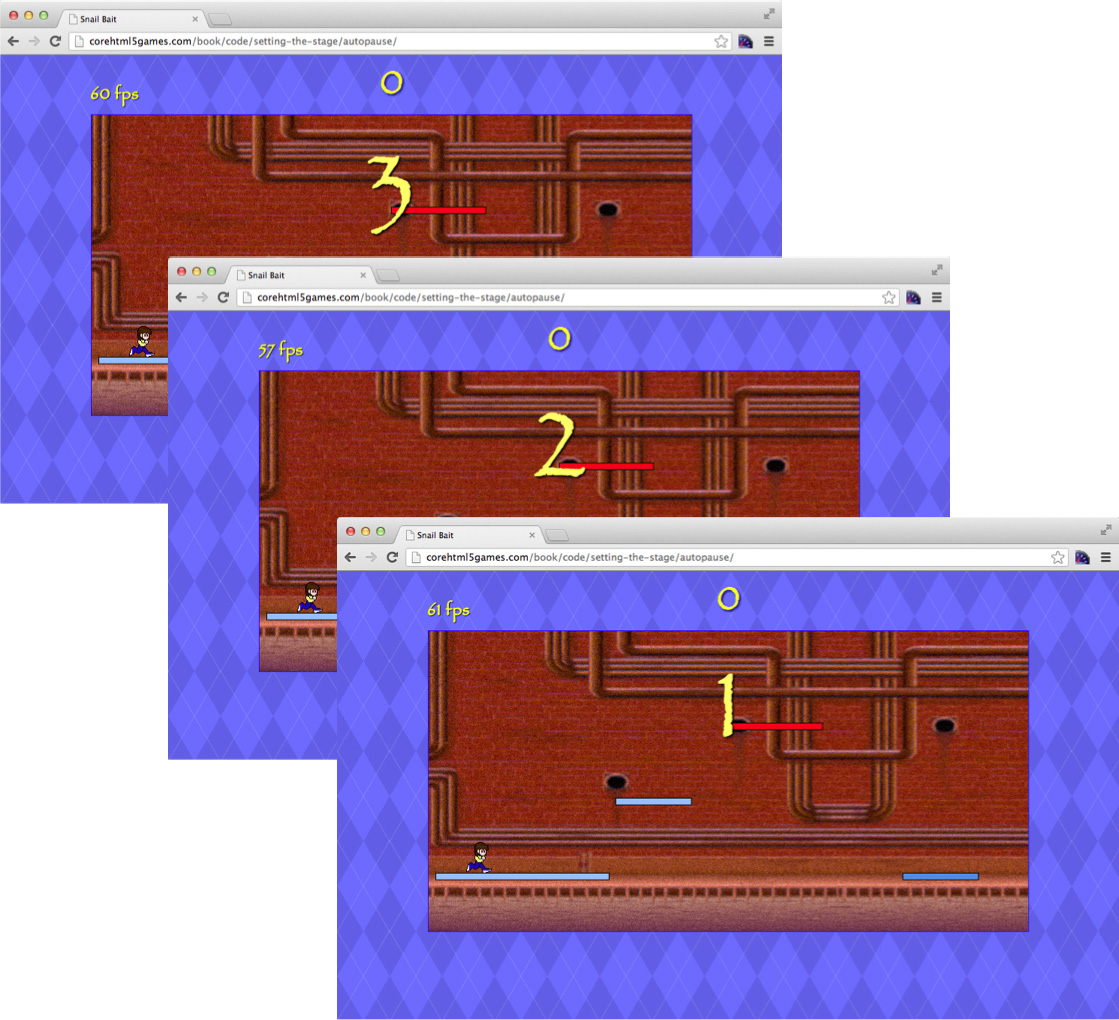

You will also see how to pause and freeze Snail Bait and subsequently how to thaw and restart the game with an animated countdown. And you’ll see how to handle keyboard events to control the runner and how to display temporary messages—known as toasts—to players. In Figure 4.1, Snail Bait reveals a toast that’s part of the three-second countdown that gives players time to regain the controls after the game’s window regains focus.

Figure 4.1. Counting down after regaining focus

In this chapter, you’ll learn how to do the following:

• Encapsulate game functions in a JavaScript object (Section 4.1, “Encapsulate Game Functions in a JavaScript Object,” on p. 96)

• Understand JavaScript’s persnickity this reference (Section 4.2, “Understand JavaScript’s Persnickety this Reference,” on p. 101)

• Handle keyboard input (Section 4.3, “Handle Keyboard Input,” on p. 104)

• Pause or resume the game when the player presses the p key (Section 4.4, “Pause or Resume the Game When the Player Presses the p Key,” on p. 106)

• Freeze the game to ensure it resumes exactly where it left off (Section 4.5, “Freeze the Game to Ensure It Resumes Exactly Where It Left Off,” on p. 107)

• Pause the game when the window loses focus (Section 4.6, “Pause the Game When the Window Loses Focus,” on p. 109)

• Resume a paused game with an animated countdown (Section 4.7, “Resume a Paused Game with an Animated Countdown,” on p. 111)

• Display toasts (brief messages) to players (Section 4.7.1, “Display Toasts (Brief Messages) to Players,” on p. 112)

Along the way, you’ll learn how to implement and instantiate JavaScript objects, how to combine CSS and JavaScript to make HTML elements appear and disappear, and how to use setTimeout() to display a countdown when a paused game resumes.

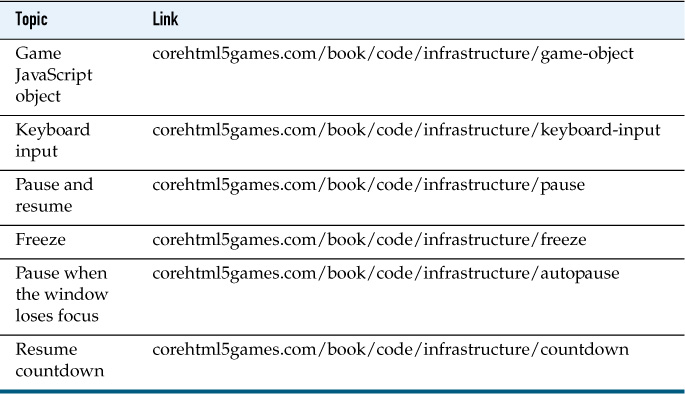

The corresponding online examples for this chapter are listed in Table 4.1.

Table 4.1. Infrastructure examples online

![]() Best Practice: Implement infrastructure up-front

Best Practice: Implement infrastructure up-front

When inspiration for a game strikes, it usually doesn’t include ingenious ways to resume a paused game, for example, so it’s natural to dive into implementing game mechanics without giving much thought to the game’s infrastructure. But as in most projects, bolting on infrastructure as an afterthought is more work than if you incorporate it from the beginning.

4.1. Encapsulate Game Functions in a JavaScript Object

Up to now, we’ve implemented all Snail Bait functions, along with several of its variables, as global variables. That, of course, will never do. Fundamentally, global variables are a bad idea because it’s too easy to inadvertently overwrite them.

Instead of using global variables, from now on we encapsulate all Snail Bait functions and variables in a single JavaScript object. By doing so, we reduce to nearly zero the odds of some other JavaScript code overwriting Snail Bait functions. For example, consider the game’s startGame() function. As a global function, it’s easy to inadvertently overwrite simply by implementing another function with the same name. However, if the same function resides in an object named SnailBait, the odds of someone unintentionally overwriting it—by assigning a function to SnailBait.startGame--is next to nil.

The SnailBait object, like all JavaScript objects, is composed of two parts: a constructor function and a prototype object. Let’s look at the constructor function first.

4.1.1. Snail Bait’s Constructor

Example 4.1 partially lists the game’s constructor.

Example 4.1. Snail Bait’s constructor (partial listing)

var SnailBait = function () {

// Variables.........................................................

this.canvas = document.getElementById('game-canvas');

this.context = this.canvas.getContext('2d');

...

// HTML elements.....................................................

this.toast = document.getElementById('toast');

this.fpsElement = document.getElementById('fps');

...

// Constants

this.LEFT = 1;

this.RIGHT = 2;

this.PLATFORM_HEIGHT = 8;

...

this.platformData = [

// Screen 1

{

left: 10,

width: 230,

height: this.PLATFORM_HEIGHT,

fillStyle: 'rgb(150,190,255)',

opacity: 1.0,

track: 1,

pulsate: false

},

// More data objects defining platforms omitted for brevity

];

...

// Many more properties are omitted for brevity

};

The SnailBait variable is a function that the JavaScript interpreter invokes when you create a new instance of SnailBait, like this: new SnailBait(). That function is known as a constructor function because it constructs the SnailBait JavaScript object, which you access in the constructor with the this variable. Constructor functions typically assign properties—such as this.LEFT or this.canvas--that are subsequently used by the object’s methods.

Snail Bait’s constructor is much longer than the listing in Example 4.1; the final version is more than 1400 lines, with substantial sections for variables, references to HTML elements, constants, and the definition of game objects, such as the platformData array listed in Example 4.1, which defines properties of the game’s platforms.

Now that you’ve seen how Snail Bait’s constructor is implemented, let’s look at the SnailBait object’s associated prototype.

4.1.2. Snail Bait’s Prototype

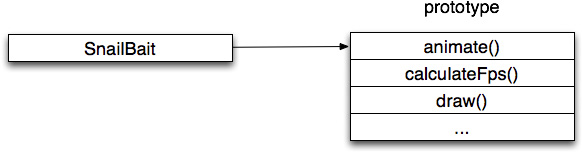

The functions associated with a JavaScript object are known as the object’s methods. They reside in a separate JavaScript object known as the prototype, as shown in Figure 4.2, which depicts the SnailBait JavaScript object and its prototype.

Figure 4.2. Snail Bait’s prototype

Example 4.2 partially lists the SnailBait object’s prototype, which at approximately 2700 lines of code is considerably longer than SnailBait’s constructor function.

Example 4.2. The game’s prototype (partial listing)

SnailBait.prototype = {

// The draw() method was discussed in [Missing XREF!]

draw: function (now) {

this.setPlatformVelocity();

this.setOffsets(now);

this.drawBackground();

this.drawRunner();

this.drawPlatforms();

},

...

// Many more methods are defined in the rest of this prototype object

};

Example 4.2 lists only the game’s draw() method. Throughout the rest of this chapter, we convert the other functions discussed in the last chapter into SnailBait object methods. In those methods you access the SnailBait JavaScript object with the this reference, just like you do in the object’s constructor, which is listed in Example 4.1. A substantial caveat comes with the this reference, however, as discussed in Section 4.2, “Understand JavaScript’s Persnickety this Reference,” on p. 101.

Now that we’ve implemented the SnailBait constructor function and its prototype, we can create an instance of SnailBait and invoke its initializeImages() method, whose implementation we discuss in Section 4.2, “Understand JavaScript’s Persnickety this Reference,” on p. 101, to start the game as shown in Example 4.3. The initializeImages() method assigns an onload event handler to the background image. That event handler, which the browser calls when the background image is fully loaded, starts the game.

Example 4.3. Creating the snailBait JavaScript object

var snailBait = new SnailBait();

snailBait.initializeImages(); // Initially discussed in [Missing XREF!]

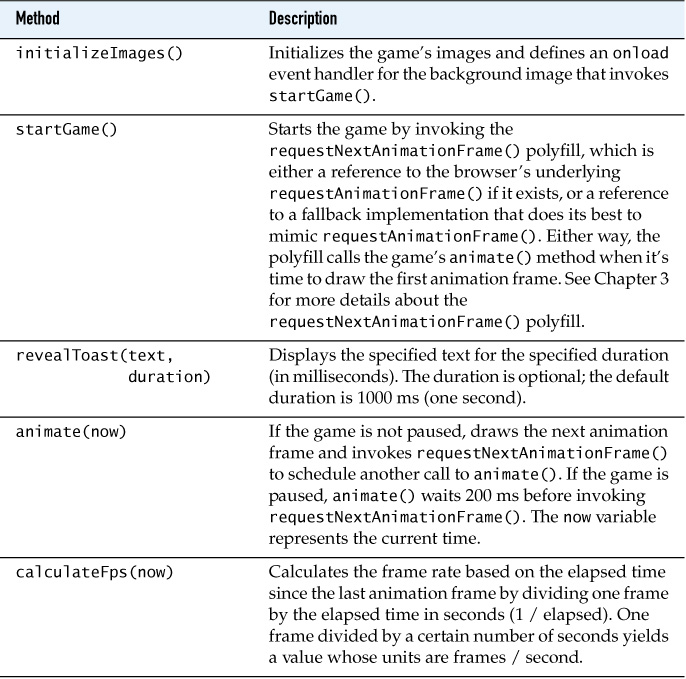

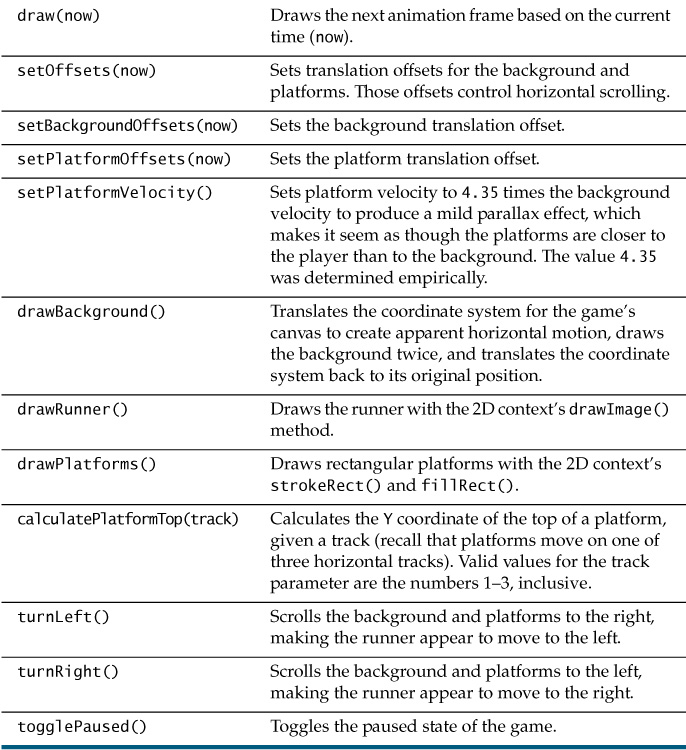

As we incorporate new features throughout this book, we will add and remove methods and also modify some method implementations. Table 4.2 lists the game’s methods as they exist as of the end of this chapter:

Table 4.2. Snail Bait methods at the end of this chapter (listed in invocation order)

![]() Note: Functions vs. methods

Note: Functions vs. methods

Functions that are members of a JavaScript object are referred to as methods, whereas standalone functions are simply called functions.

4.2. Understand JavaScript’s Persnickety this Reference

In Section 4.1, “Encapsulate Game Functions in a JavaScript Object,” on p. 96 you saw how to access the SnailBait JavaScript object with the this operator in its constructor function and methods. Unlike the this reference in other computer languages, however, JavaScript’s this reference sometimes refers to a different JavaScript object, depending on who called the enclosing method.

For example, consider the animate() function discussed in Chapter 3, and relisted in Example 4.4.

Example 4.4. The animate() function

function animate(now) {

fps = calculateFps(now);

draw(now);

lastAnimationFrameTime = now;

requestNextAnimationFrame(animate);

}

The preceding animate() function makes assignments to two global variables and invokes two global functions. You might easily be misled by Example 4.2, which lists Snail Bait’s draw() function, into thinking that you can turn those variables and functions into SnailBait properties and methods, as shown in Example 4.5.

Example 4.5. A naive implementation of Snail Bait’s animate() method

// WARNING: DO NOT DO THIS, IT DOES NOT WORK...

SnailBait.prototype = {

...

// Implementations of calculateFps() and

// requestNextAnimationFrame() are omitted for brevity.

animate: function (now) {

this.fps = snailBait.calculateFps(now); // this is not Snail Bait!

this.draw(now); // It's the window object.

this.lastAnimationFrameTime = now;

requestNextAnimationFrame(this.animate);

},

...

};

The preceding implementation of the animate() method does not work because the this reference in the animate() method refers to the window object, not the SnailBait object. That’s because the browser calls the animate() method (when the underlying requestAnimationFrame() method is available; see Chapter 3 for details).

Because the this reference in Snail Bait’s animate() method refers to the window object and not the SnailBait object, the animate() method references the SnailBait object directly, as shown in Example 4.6.

Example 4.6. The animate() method

SnailBait.prototype = {

...

// ...DO THIS INSTEAD OF THE PREVIOUS EXAMPLE.

animate: function (now) {

snailBait.fps = snailBait.calculateFps(now);

snailBait.draw(now);

snailBait.lastAnimationFrameTime = now;

requestNextAnimationFrame(snailBait.animate);

},

...

};

var snailBait = new SnailBait();

The fact that JavaScript’s this reference can change depending on who invokes a particular method is frustrating enough; however, this JavaScript oddity is even more insidious than it first appears because sometimes the this operator can change in the middle of a method. Consider the initializeImages() function listed in Example 4.7.

Example 4.7. The initializeImages() function

function initializeImages() {

background.src = 'images/background.png';

runnerImage.src = 'images/runner.png';

background.onload = function (e) {

startGame();

};

}

Example 4.8 shows the initializeImages() function converted into a SnailBait method.

Example 4.8. The initializeImages() method

SnailBait.prototype = {

...

// Snail Bait calls the initializeImages() method directly

initializeImages: function() {

this.background.src = 'images/background.png';

this.runnerImage.src = 'images/runner.png';

// The browser calls the onload event handler

background.onload = function (e) {

snailBait.startGame();

};

}

...

};

Because Snail Bait calls the initializeImages() method directly, the this reference in that method refers to the SnailBait JavaScript object, and we can access its background and runnerImage properties. However, the browser invokes the background image’s onload event handler, and therefore the this reference within that event handler is once again the window object, so we access the snailBait object directly inside that event handler.

![]() Note: Be skeptical of your interpretation of the

Note: Be skeptical of your interpretation of the this reference.

If you’ve used classic object-oriented programming languages such as C++ or Java, you will undoubtedly find that a high percentage of the bugs you run into involve your misinterpretation of the this reference. That interpretation should be the first thing you examine when debugging troublesome code.

![]() Note: Other strategies for dealing with JavaScript’s

Note: Other strategies for dealing with JavaScript’s this reference

Snail Bait deals with the chameleon-like nature of JavaScript’s this reference by directly using the snailBait reference when the this reference does not refer to the game. There are other strategies, however, for dealing with the this reference, such as the popular Module pattern in JavaScript. (See www.adequatelygood.com/JavaScript-Module-Pattern-In-Depth.html for an excellent explanation of the Module pattern.)

Another option when the this reference changes in the middle of a method, as illustrated above, is to create a variable—typically named self—in the method and assign it to the this reference. Subsequently, when the this reference does not refer to the game, you can use the self reference instead.

You can also simply use the snailBait reference everywhere throughout the game. That may be the simplest and most effective strategy; however, Snail Bait uses both this and snailBait, so you can see places in the code where the this reference changes.

4.3. Handle Keyboard Input

When Snail Bait begins, its background is stationary. The background starts to scroll when the player presses either the d or left arrow keys to make it appear as though the runner is moving to the left or the k or right arrow keys to make it appear as though the runner is moving to the right.

You can attach key event handlers only to focusable HTML elements, such as text fields and windows, and Snail Bait takes place in a canvas element, which is not a focusable element. Therefore, because we cannot attach a key event handler to Snail Bait’s canvas, we attach it to the game’s window, as shown in Example 4.9.

Example 4.9. Mapping keys to change direction

window.addEventListener('keydown', function (e) {

var key = e.keyCode;

if (key === 68 || key === 37) { // 'd' or left arrow

snailBait.turnLeft();

}

else if (key === 75 || key === 39) { // 'k'or right arrow

snailBait.turnRight();

}

});

The preceding event handler invokes Snail Bait’s turnLeft() method or turnRight() method depending on the key the player pressed. Those methods are listed in Example 4.10.

Example 4.10. Snail Bait’s turnLeft() and turnRight() methods

SnailBait.prototype = {

...

turnLeft: function () {

this.bgVelocity = -this.BACKGROUND_VELOCITY; // pixels/second

...

},

turnRight: function () {

this.bgVelocity = this.BACKGROUND_VELOCITY; // pixels/second

...

},

...

};

Once again it’s interesting to note that Snail Bait implements horizontal motion by translating the coordinate system for the game’s drawing surface, which makes the implementations of turnLeft() and turnRight() as simple as possible by merely reversing the background’s direction.

![]() Note: JavaScript keycodes

Note: JavaScript keycodes

You can find out the JavaScript keycodes for Latin-based languages at www.cambiaresearch.com/articles/15/javascript-char-codes-key-codes.

![]() Note:

Note: addEventListener() vs. onkeydown

You can add event handlers to HTML elements in one of two ways. One way is to assign a function to a property of the element’s corresponding JavaScript object, such as the onblur property of the window object. Another way is to call JavaScript’s addEventListener() method to add a handler to a list of functions that the browser invokes for a particular event. For example, instead of assigning the function to the window object’s onblur property, you can add a blur event handler with the addEventListener() method.

All other things being equal, you should prefer addEventListener() to properties such as onblur. The reasoning behind that preference is that it’s easy to inadvertently override properties such as onblur.

4.4. Pause or Resume the Game When the Player Presses the p Key

HTML5 games and especially video games must be able to pause. Example 4.11 shows a first cut at pausing and resuming Snail Bait.

Example 4.11. Pause and resume

var SnailBait = function () {

...

this.paused = false,

this.PAUSED_CHECK_INTERVAL = 200; // milliseconds

...

};

SnailBait.prototype = {

...

togglePaused: function () {

this.paused = !this.paused;

},

animate: function (now) {

if (snailBait.paused) {

// Try again later

setTimeout( function () {

requestNextAnimationFrame(snailBait.animate);

}, snailBait.PAUSED_CHECK_INTERVAL);

}

else {

// Game loop

snailBait.fps = snailBait.calculateFps(now);

snailBait.draw(now);

snailBait.lastAnimationFrameTime = now;

requestNextAnimationFrame(snailBait.animate);

}

},

...

};

The togglePaused() method simply toggles the game’s paused variable. When that variable’s value is true, it means that the game is paused so the animate() method does not execute the game loop.

It’s neither necessary nor efficient to check 60 times per second (assuming a frame rate of 60 fps) to see if it’s time to resume a paused game; therefore, the animate() method in Example 4.11 waits 200 ms before invoking the requestNextAnimationFrame() polyfill, which schedules another call to animate() when it’s time to draw the next animation frame.

![]() Note: The 200 ms threshold and user interface latency

Note: The 200 ms threshold and user interface latency

When Snail Bait is paused, it waits 200 ms between checks to see if the game has resumed. The 200 ms number is widely regarded as the threshold at which applications feel sluggish, so Snail Bait ensures that players never have to wait longer than that threshold when the game’s window regains focus. See http://ajaxian.com/archives/craftmanship-and-ui-latency to read more about user interface latency.

![]() Note:

Note: setTimeout() and setInterval() are useful functions

As you saw in Chapter 3, you should never use setTimeout() and setInterval() for time-critical animations; however, those methods are indispensable for timing things like user interface effects.

![]() Best Practice: Don’t do everything at full speed

Best Practice: Don’t do everything at full speed

Games do many things that should not be done every animation frame. For example, in addition to checking for the resumption of a paused game, Snail Bait also updates the game’s frames per second display once per second.

4.5. Freeze the Game to Ensure It Resumes Exactly Where It Left Off

Pausing a game involves more than simply halting its animation. Games must resume exactly where they left off. The code in Example 4.11 may appear to fill that requirement; after all, while the game is paused, nothing happens, so it seems as though the game should resume exactly as it was before it was paused. However, that’s not the case, because the primary currency for all animations—Snail Bait’s included—is time.

As you saw in Chapter 3, after you call requestAnimationFrame(), the browser invokes a callback function you specify, passing that function the current time. In Snail Bait’s case, that callback is the animate() method, which in turn passes the time to the draw() method. See Chapter 3 for more information about requestAnimationFrame() and the time that the browser passes to the animate() method.

Even though the animation does not run while the game is paused, time still marches on unabated. And because Snail Bait’s draw() method draws the next animation frame based on the time it receives from animate(), the previous implementation of togglePaused() in Example 4.11 causes the game to lurch ahead in time when the paused game resumes.

Example 4.12 shows a revised implementation of togglePaused() that avoids an abrupt time shift when the paused game resumes.

Example 4.12. Freezing the game (togglePaused() revisited)

var SnailBait = function () {

...

this.paused = false,

this.pauseStartTime = 0,

this.lastAnimationFrameTime = 0,

...

};

SnailBait.prototype = {

...

togglePaused: function () {

var now = +new Date();

this.paused = !this.paused;

if (this.paused)

this.pauseStartTime = now;

}

else {

this.lastAnimationFrameTime += (now - this.pauseStartTime);

}

},

};

When the player pauses the game, the preceding implementation of togglePaused() toggles the paused property and stores the current time in the pauseStartTime property.

When the game resumes, togglePaused() again toggles the paused property and calculates the amount of time the game was paused. The togglePaused() method then moves the time of last animation frame ahead by the amount of time the game was paused, which erases the pause. Subsequently, the game resumes exactly where it left off when the pause began.

![]() Caution: Snail Bait doesn’t always tell the truth

Caution: Snail Bait doesn’t always tell the truth

Snail Bait stores the time of the last animation frame in its lastAnimationFrameTime property. Until the game is paused for the first time, that property’s value reflects the actual time of the last animation frame. However, as you saw in the last section, when a player resumes a paused game, that value deviates from reality.

In Chapter 10 we discuss the implementation of Snail Bait’s time system, which is also less than truthful about how long the game has been running to slow time or to speed it up.

4.6. Pause the Game When the Window Loses Focus

If your game is running in a window or tab that’s not visible and you’re using requestAnimationFrame(), then according to the W3C specification:

If the page is not currently visible, animations on that page can be throttled heavily so that they do not update often and thus consume little CPU power.

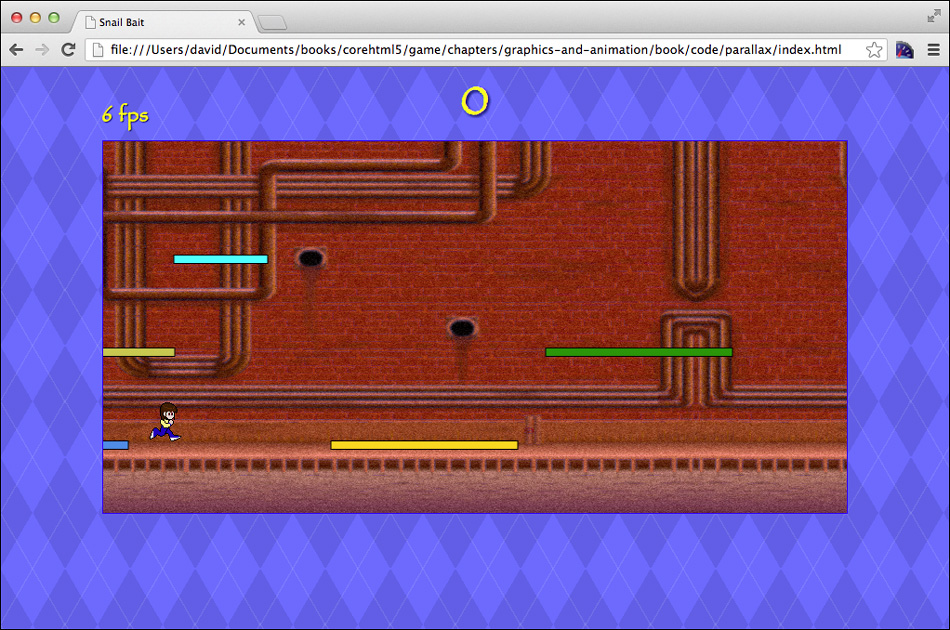

The term throttled heavily means the browser invokes your animation callback at an abysmal frame rate, usually somewhere between 1 and 10 fps, as illustrated by Figure 4.3, which shows a frame rate of 6 fps immediately after the window has regained focus.

Figure 4.3. Browsers heavily throttle frame rate when a tab is not visible

Heavily throttled frame rates can wreak havoc on collision-detection algorithms, because a sudden increase in the amount of time between animation frames can cause sprites to pass one another without colliding, as is the case when the browser heavily throttles the frame rate.

You can avoid collision-detection meltdowns resulting from heavily throttled frame rates by pausing the game when the game’s window loses focus and restarting it when the window regains focus. You can see how to do that in Example 4.13.

window.addEventListener('blur', function (e) {

if (!snailBait.paused) { // If the game is not paused,

snailBait.togglePaused(); // pause

}

});

window.addEventListener('focus', function (e) {

if (snailBait.paused) { // If the game is paused,

snailBait.togglePaused(); // resume

}

});

![]() Best Practice:

Best Practice:

Pause the game when the window loses focus and resume when it regains focus.

4.7. Resume a Paused Game with an Animated Countdown

When your game resumes after its window receives focus, you should give players a few seconds to regain the controls. During that time, it’s a good idea to provide feedback concerning the amount of time remaining before the game resumes.

When Snail Bait’s window regains focus, it displays a three-second countdown to give players time to get ready, as shown in Figure 4.4.

Figure 4.4. Snail Bait after losing and regaining focus

Snail Bait implements its countdown with a toast, so we begin this discussion of that countdown with toasts.

4.7.1. Display Toasts (Brief Messages) to Players

The numerals that Snail Bait displays during the countdown—along with other briefly displayed messages throughout the game—are text in an HTML DIV element, known as the game’s toast. That DIV is declared in the game’s HTML file with a snailbait-toast ID, as shown in Example 4.14.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

...

</head>

<body>

<div id='snailbait-arena'>

<!-- Toast..................................................-->

<!-- Initially empty and invisible -->

<div id='snailbait-toast'></div>

...

</div>

</body>

</html>

The browser displays the snailbait-toast element on top of the canvas by virtue of its z-index CSS attribute whose value, as you can see from Example 4.15, is 1. By default, the snailbait-canvas element’s z-index is zero, and therefore the browser displays the DIV on top of the canvas. The DIV however, is not initially visible because its display attribute’s value is none.

#snailbait-toast {

position: absolute;

margin-left: 100px;

margin-top: 20px;

...

z-index: 1;

display: none;

}

Snail Bait reveals the toast DIV with its revealToast() method, which is listed in Example 4.16.

Example 4.16. Revealing toasts in JavaScript

var SnailBait = function () {

...

this.DEFAULT_TOAST_TIME = 3000; // 3 seconds

this.toast = document.getElementById('snailbait-toast');

...

};

SnailBait.prototype = {

...

revealToast: function (text, howLong) {

var DEFAULT_TOAST_DISPLAY_DURATION = 1000;

howLong = howLong || DEFAULT_TOAST_DISPLAY_DURATION;

this.toast.style.display = 'block'; // Show the toast DIV

this.toast.innerHTML = text; // with the specified text

setTimeout( function (e) {

if (snailBait.windowHasFocus) {

snailBait.toast.style.display = 'none'; // Hide the toast DIV

}

}, howLong);

},

...

}

The revealToast() method displays a string in the toast DIV for a particular duration. You can specify that duration with revealToast()’s optional second argument. If you call revealToast() with only the first argument, the duration defaults to one second.

4.7.2. Snail Bait’s Countdown

Snail Bait displays each numeral in the countdown for a total of one second. Example 4.17 shows the JavaScript for the countdown.

When Snail Bait’s window regains focus, it starts the countdown, displaying each numeral for one second. Once the countdown reaches zero, the focus event handler calls togglePaused() to resume the game.

Example 4.17. Countdown JavaScript

var SnailBait = function () {

...

this.toast = document.getElementById('toast'),

};

window.addEventListener('blur', function (e) {

if (!snailBait.paused) {

snailBait.togglePaused(); // Pause if not paused

}

});

window.addEventListener('focus', function (e) {

var originalFont = snailBait.toast.style.fontSize, // restore later

DIGIT_DISPLAY_DURATION = 1000; // milliseconds

if (snailBait.paused) {

snailBait.toast.style.font = '128px fantasy'; // Large font

snailBait.revealToast('3', 1000); // Display 3 for 1.0 seconds

setTimeout(function (e) {

snailBait.revealToast('2', 1000); // Display 2 for 1.0 seconds

setTimeout(function (e) {

snailBait.revealToast('1', 1000); // Display 1 for 1.0 seconds

setTimeout(function (e) {

snailBait.togglePaused();

snailBait.toast.style.fontSize = originalFont;

}, DIGIT_DISPLAY_DURATION); // End of '1'

}, DIGIT_DISPLAY_DURATION); // End of '2'

}, DIGIT_DISPLAY_DURATION); // End of '3'

}

});

The code in Example 4.17 does not work properly, however, if a player activates another window or tab during the countdown, because the game will restart at the end of the countdown whether the window has focus or not. That’s easy enough to fix with windowHasFocus and countdownInProgress flags, as shown in Example 4.18.

Example 4.18. Accounting for lost focus during the countdown

window.addEventListener('blur', function (e) {

snailBait.windowHasFocus = false;

if (! snailBait.paused) {

snailBait.togglePaused(); // pause if not paused

}

});

window.addEventListener('focus', function (e) {

var originalFont = snailBait.toastElement.style.fontSize,

DIGIT_DISPLAY_DURATION = 1000; // milliseconds

snailBait.windowHasFocus = true;

snailBait.countdownInProgress = true;

if (snailBait.paused) {

snailBait.toastElement.style.font = '128px fantasy'; // Large font

if (snailBait.windowHasFocus && snailBait.countdownInProgress)

snailBait.revealToast('3', 1000); // Display 3 for 1.0 seconds

setTimeout(function (e) {

if (snailBait.windowHasFocus && snailBait.countdownInProgress)

snailBait.revealToast('2', 1000); // Display 2 for 1.0 seconds

setTimeout(function (e) {

if (snailBait.windowHasFocus && snailBait.countdownInProgress)

snailBait.revealToast('1', 1000); // Display 1 for 1.0 seconds

setTimeout(function (e) {

if ( snailBait.windowHasFocus && snailBait.countdownInProgress)

snailBait.togglePaused();

if ( snailBait.windowHasFocus && snailBait.countdownInProgress)

snailBait.toastElement.style.fontSize = originalFont;

snailBait.countdownInProgress = false;

}, DIGIT_DISPLAY_DURATION);

}, DIGIT_DISPLAY_DURATION);

}, DIGIT_DISPLAY_DURATION);

}

});

When the window loses focus, it sets the windowHasFocus attribute to false. When it regains focus, it sets the attribute to true, begins the countdown and sets the countdownInProgress attribute to true. Subsequently, the focus event handler only executes the steps of the countdown if the window still has focus and a countdown is in progress.

![]() Best Practice:

Best Practice:

Give players time to regain the controls when the game’s window regains focus.

4.8. Conclusion

This chapter sets the stage for the rest of the book by encapsulating Snail Bait’s code in a single global JavaScript object named SnailBait and by implementing fundamental infrastructure such as pausing and resuming the game when the window loses and regains focus, respectively.

When you pause your game, it’s not enough to merely disengage the game’s animation. That’s because time marches on and when players resume the game, you must account for the time the game was paused to avoid a noticeable time discontinuity.

It’s also a good idea to give players a few seconds to regain the controls when your game regains focus. You saw how to do that in this chapter, and you also saw how to implement a three-second countdown that gives players visual feedback as the countdown progresses.

In the next chapter, we continue implementing Snail Bait’s basic infrastucture with the implementation of the game’s loading screen.

4.9. Exercises

1. Run the pause and freeze examples from this chapter at corehtml5-games.com/book/code/infrastructure/pause and corehtml5games.com/book/code/infrastructure/freeze, respectively, and start and stop each example by pressing the p key. Notice the lurch forward in time in the pause example when the window regains focus versus the smooth transition to play in the freeze example.

2. Change the JavaScript in the corehtml5games.com/book/code/infrastructure/game-object example to use snailBait everywhere instead of this in Snail Bait’s constructor and methods.

3. Change the initializeImages() method to use the self technique described in Section 4.2, “Understand JavaScript’s Persnickety this Reference,” on p. 101.