CHAPTER 12

Liquidity Options Beyond a Sale

INTRODUCTION1

In Chapter 11, we noted that mature, successful FinTech companies, particularly the largest, most highly valued ones, are difficult to acquire given their size and valuation, which limits the pool of potential buyers.

Recent market trends are favorable for FinTech; however, these trends may not last indefinitely and any slowdown could temper M&A activity and liquidity options for FinTech companies. Should market conditions cool and exit options through a traditional sale be limited, FinTech companies and their stakeholders, which will likely increasingly include banks, may need a strategy adjustment to include liquidity options other than a traditional sale to a third‐party. Consequently, this chapter discusses liquidity alternatives other than a third‐party sale and may be particularly relevant for FinTech entrepreneurs, bankers, and their stakeholders.

Some of the best tennis players have the ability to alter their game depending upon the conditions and add a wrinkle in important moments that their opponent has previously not seen before. Similar to a great baseline tennis player who adapts his or her game and commits to moving forward in the court more on grass (a court surface that rewards that strategy more), FinTech founders and investors may need to consider a strategy adjustment depending upon market and industry conditions present. These strategic options can be extremely important to entrepreneurs and shareholders of FinTech companies, as they ultimately determine the potential returns that they will receive for their investments.

While institutional investors often have a portfolio of investments and the performance of one can offset the lack of performance of the other, the net worth of individual owners of private FinTech companies can be concentrated in the company itself and this can be dangerous. For example, let's consider the portfolio of Mr. Smith, a successful FinTech entrepreneur who helped found a FinTech company, grow it into a successful and profitable operation, and now has a significant ownership position in the company. Mr. Smith's net worth is highly concentrated in the stock of his private FinTech company. Therefore, creating value and measuring and managing returns from this private company investment are extremely important to him. Liquidity is also a primary concern to investors and owners like Mr. Smith as investments in private companies are often illiquid, which creates a difficult situation for those investors seeking some diversification of their interest given their concentrated positions (See Figure 12.1).

FIGURE 12.1 Mr. Smith's Portfolio Including His FinTech Portfolio

This combination of concentrated positions in private companies and a desire for liquidity among the investors is often one reason that companies look to a traditional exit like a third‐party sale. However, sometimes a third‐party sale is not possible given market, industry, or other conditions. For owners such as Mr. Smith, we discuss other liquidity options.

LIQUIDITY OPTIONS

Other avenues for liquidity aside from a third‐party sale are detailed in Table 12.1 and we discuss options under each strategy (“Holding On,” “Selling In,” or “Selling Out”) in the sections that follow.

TABLE 12.1 Liquidity Options

| Selling In | Selling Out | |

| Holding On | (Family, Management) | (Financial Buyer, Strategic Buyer) |

| Dividends (Regular, Special, Leveraged Recap) | Management Buy‐In | Private Equity |

| Share Redemptions | ESOP | Third‐Party Sale (Financial Buyer) |

| Generational Transfers | Third‐Party Sale (Strategic Buyer) | |

| Trust Ownership | IPO |

Holding On

This section discusses considerations for those FinTech companies that elect to “hold on” and make the financial decision to pass on reinvesting in the business and return a flexible, indeterminate amount of those earnings to shareholders in the form of shareholder dividends or share repurchases.

Dividends

Dividends correspond to the portion of earnings available for distribution after paying all taxes and accounting for all net reinvestment in the business. Mature FinTech companies and banks that are generating earnings consistently will want to consider their dividend policies. Below we list a few common dividend policies for companies and the types of companies that most benefit from having those policies.

- No Dividend Paid at All. Companies paying no dividends include those that pay no dividends ($0 in dividend payments) and S corporations whose shareholders/members/partners receive no economic dividend as they only receive distributions sufficient enough so that they can pay their pro‐rata share of the taxes owed.

- Sporadic, Onetime, or Special Dividends. Companies with this type of dividend policy typically pay a dividend for specific reasons applicable at the time the dividend is paid. For example, the company may have volatile earnings depending upon the business cycle or an extremely profitable period or unusual, nonrecurring income that results in a special or onetime dividend.

- Targeted Dividend Payouts. Companies paying targeted dividend payouts typically have either a target dividend payout ratio (e.g., 40% of after‐tax earnings), a targeted dividend yield (2% of the concluded value of the business), or a constant‐dollar dividend (i.e., $2 million dividend per year).

- Spinout or Spinoff of Subsidiaries or Assets. Companies that spin out or spin off subsidiaries or assets take some subsidiary or division of the company and create a separate operating company. Interestingly, there have been a number of famous spinoffs of FinTech companies. One FinTech example is eBay and PayPal, but there have been others, including a number of payments companies that have been spun out of retail banks.

- Some Combination of Items 1–4.

For banks, the question of whether to reinvest in the business or distribute cash is often uniquely different than for those FinTech companies. Often, banks are mature businesses that tend to have more limited growth prospects compared to FinTech companies, which leads them to often return cash flows and capital to shareholders in the form of dividends. For FinTech companies, the growth prospects are often higher than their traditional bank counterparts, and thus they often have more opportunities to create value through forgoing dividends and reinvesting earnings in capital projects that generate returns in excess of their cost of capital. However, mature banks do have the opportunity to take a portion of the cash flows generated and invest in these FinTech companies, or in their own technology groups to develop platforms that can capitalize on the potential growth within FinTech and ultimately create value for their institution.

Share Repurchases

Share repurchases may be a more favored use of capital than shareholder dividends when shareholders have diverse preferences in terms of what they desire for their shareholder return. For example, share repurchases allow those shareholders looking to sell their interest for whatever reason to be able to sell and then the remaining shareholders can benefit from capital appreciation following the repurchase. In order to facilitate repurchases, though, there must be a price that is deemed fair to both those selling shareholders and the remaining shareholders as well as cash flow available from the company to repurchase. Should the price paid for the repurchases be too high, then the selling shareholders benefit at the expense of those who remain after the repurchase. If the price paid is too low, then the remaining shareholders benefit at the expense of the sellers.

Selling In

Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOPs)

Another potential alternative to enhance liquidity is by selling a portion of the company to managers and employees through an Employee Stock Ownership Plan. ESOPs are often an important omission in the boardroom as a number of companies lack an understanding of the possible ways that an ESOP can solve a number of strategic and liquidity issues. ESOPs provide one option to maintain independence and enhance stock liquidity absent an outright sale or an IPO. ESOPs are a written, defined contribution retirement plan designed to qualify for some tax‐favored treatments under IRC Section 401(a). While similar to a more typical profit‐sharing plan, the fundamental difference is that the ESOP must be primarily invested in the stock of the sponsoring company (only S or C corporations).

ESOPs can acquire shares through employer contributions (in either cash or existing/newly issued shares) or by borrowing money to purchase stock (existing or newly issued) of the sponsoring company. When compared to other retirement plans, the ability to borrow money to purchase stock is an attribute that is fairly unique to ESOPs. Once holding shares, the ESOP obtains cash via sponsor contributions, borrowing money, or dividends/distributions on shares held by the ESOP. When an employee exits the plan, the sponsoring company must facilitate the repurchase of the shares, and the ESOP may use cash to purchase shares from the participant. Following repurchase, those shares are then reallocated among the remaining participants.

While ESOPs or some variant of them may be prevalent in other countries and their tax attributes will vary depending upon the country, ESOPs can potentially provide significant tax benefits here in the United States and we will discuss those briefly. Similar to other profit‐sharing plans, contributions (subject to certain limitations) to the ESOP are tax‐deductible to the sponsoring company. The ESOP is treated as a single tax‐exempt shareholder. This can be of particular benefit to S corporations, as the earnings attributable to the ESOP's interest in the sponsoring company are untaxed. The tax liability related to ESOP plan holder's accounts is at the participant level and generally deferred similar to a 401(k) until employees take distributions from the plan. When leverage is involved (i.e., the ESOP borrows money to purchase shares), the potential tax benefits can be extremely large as the ESOP is able to effectively deduct (and get the associated tax benefit on) both principal and interest payment.

Both publicly traded and privately owned companies (C or S corporations) can sponsor ESOPs, but the benefits are often more profound for private institutions that are not as actively traded because the ESOP can promote a more active market and enhance liquidity more for the privately held shares.

An ESOP can help to solve a number of strategic issues, including the following:

- Facilitating Stock Purchases and Providing Liquidity Absent an Outright Sale/IPO. ESOPs can help create an “internal” stock market. By creating an “internal” stock market, the transaction activity between existing shareholders and the ESOP, which serves as a buyer, can promote confidence in stock pricing. For C corporations, the selling shareholder may even have the ability to sell their shares in a tax‐free manner subject to certain limitations.2

- Providing Employee Benefits. ESOPs can provide a beneficial tool to reward and attract key employees. ESOPs offer the benefit of stock in the company absent any direct cost to the employees by providing them with common stock. The structure of ESOPs varies, but ESOPs typically tie rewards directly to the long‐term performance of the company. A recent study by Ernst & Young found that the total return for S corporation ESOPs from 2002 to 2012 was a compound annual growth rate of 11.5 percent compared to the total return of the S&P 500 over the same period, which was 7.1 percent.3 The measure of S corporation ESOP returns considers cumulative distributions as well as growth in value of net assets and the net of those distributions (i.e., growth in the underlying value per share).

- Creating Long‐Term Shareholder Value by Properly Aligning Incentives between Employees and Shareholders.

- Augmenting Capital. While it typically occurs more slowly than through a private placement or a public offering, an ESOP strategy can provide certain tax advantages that can help to build capital and/or pay down existing debt.

Despite the potential benefits to an ESOP, there are some potential negatives to them. Here we have listed a few:

- Plans are regulated primarily by the Department of Labor and also the IRS (Internal Revenue Service) can review plan activities.

- The sponsoring company will need to have sufficient cash flow to be able to provide contributions to the ESOP so that the ESOP can manage its repurchase obligation as the ESOP participants receive cash (not stock) for their vested retirement plan payouts.

- There are some administrative costs with setting up and maintaining the plans.

- An ESOP can spread ownership/transparency to the employee base, which for some companies can be viewed as a negative.

- There can be some dilution to the existing shareholder if newly issued shares are purchased by the ESOP.

For those considering an ESOP, the first step is a feasibility study of what the ESOP would look like once implemented at your company. Parts of the study would include determining the value of the company's shares, the pro‐forma implications from the potential transaction/installation, as well as what after‐tax proceeds the seller might expect. This will help to determine whether the company should proceed, wait a few years to implement, or move to another strategic option. There are typically a number of parties involved in implementations, including, among others, the appraiser/valuation provider, trustee, attorney or plan designer, and administrative committee.

Selling Out

Initial Public Offerings (IPOs)

Initial public offerings offer another way for shareholders of private companies to achieve liquidity. Typically, the private company transforms to a public one after completing the public offering as the shares are sold to institutional investors and then to the public after being listed on an exchange. The motivation for initiating an IPO is not always to achieve liquidity for shareholders. Other motivations can include raising capital or expanding access to capital for the company. One offset to these potential advantages for shareholders is that IPOs can be relatively costly to undertake the process and public companies are often required to disclose greater financial information to the public on an ongoing basis (which can also be costly to provide and comply with disclosure requirements).

The IPO of Netscape, a computer services company that was relatively well known for a web browser that it created, in the mid‐1990s was a seminal moment in the technology industry. Netscape was founded in April 1994 and in approximately 18 months had an extremely successful IPO despite not yet being profitable. The IPO was initially priced at $14 per share before being offered initially at $28 per share and then closing at $58.25 per share, which implied a valuation for Netscape at roughly $3 billion, at the end of the first trading day.

Due to its rousing success, Netscape's story received widespread attention and generated significant proceeds for many of its early investors and employees, including a book written by Michael Lewis entitled The New New Thing (W.W. Norton & Company; January 6, 2014). Netscape's story provided a template for many technology entrepreneurs and investors to follow. Netscape's template basically became the playbook for a number of technology companies, and its strategy was relatively straightforward: develop a blueprint for a technology solution that can be applied to a large potential market, pitch the blueprint to the venture capitalists, raise money, gather the team, execute the business plan and develop the product, and then prepare for an exit in the form of either an IPO or strategic sale. Ironically, though, this template seems to be met with resistance by some entrepreneurs today. Even Marc Andreessen, one of Netscape's founders, has been on record downplaying the role of the IPO in today's market environment.

A number of technology companies and entrepreneurs have attempted to follow Netscape's track and develop their technology platforms and business models, including a successful IPO as their primary exit strategy. However, that has started to change somewhat in recent years as technology IPOs have faced increased levels of scrutiny and many private companies are staying private longer as ample funding has been available, limiting their need to undertake the time‐consuming and costly process to access capital and liquidity in the public markets.

While FinTech is an emerging and growing industry, there are examples of FinTech IPOs. Table 12.2 provides the largest FinTech IPOs of all time. Payments companies (Visa, First Data, and MasterCard) represent the largest FinTech IPOs in terms of proceeds raised. Insurance/healthcare solutions are also relatively well represented. Interestingly, some of the areas that receive most of the media attention, like alternative lending, blockchain, and wealth management solutions, have yet to raise enough proceeds in a public offering to make the list of top FinTech IPOs.

TABLE 12.2 Top FinTech IPOs

Sources: SNL Financial and Capital IQ

| Ticker | Name | IPO Price | IPO Date | Gross Proceeds | % Return Since IPO | 6/30/16 Price | 6/30/16 Market Cap. ($M) | 6/30/16 Ent. Value | FinTech Niche |

| V | Visa Inc. | 44.00 | 3/18/08 | 19,650.40 | 68.6% | 74.17 | 176,889 | 189,733 | Payment Processors |

| FDC | First Data Corp. | 16.00 | 10/14/15 | 2,817.23 | −30.8% | 11.07 | 10,046 | 31,922 | Payment Processors |

| MA | MasterCard Inc. | 39.00 | 5/24/06 | 2,579.27 | 125.8% | 88.06 | 96,752 | 93,643 | Payment Processors |

| VRSK | Verisk Analytics Inc. | 22.00 | 10/6/09 | 2,155.91 | 268.5% | 81.08 | 13,635 | 15,710 | Financial Media & Content |

| IMS | IMS Health Holdings Inc. | 20.00 | 4/3/14 | 1,495.00 | Acq'd | na | na | na | Insurance/Healthcare Solutions |

| INFO | IHS Markit Ltd. | 24.00 | 6/18/14 | 1,475.84 | 35.8% | 32.60 | 5,840 | 6,529 | Financial Media & Content |

| LC | Lending Club Corp. | 15.00 | 12/10/14 | 1,000.50 | −71.3% | 4.30 | 1,641 | 1,068 | Alternative Lender |

| PINC | Premier Inc. | 27.00 | 9/25/13 | 874.12 | 21.1% | 32.70 | 1,490 | 1,242 | Insurance/Healthcare Solutions |

| TRU | Trans Union | 22.50 | 6/24/15 | 764.49 | 48.6% | 33.44 | 6,108 | 8,514 | Financial Media & Content |

| WDAY | Workday Inc. | 28.00 | 10/11/12 | 732.55 | 166.7% | 74.67 | 14,710 | 13,144 | Payroll & Admin. Solutions |

IS YOUR BUY–SELL AGREEMENT SOLIDLY BUILT?

This question is important for FinTech entrepreneurs and bankers alike to ensure that their companies are built to last. We have seen over the years a number of situations where a company's strategic options were impacted by improperly constructed buy–sell agreements. At Mercer Capital, we have a unique perspective on buy–sell agreements, having written a number of articles and books on them and also been involved in disputes where the buy–sell agreement and valuation issues are the centerpiece. While we are not lawyers who draft these agreements, we are often asked to interpret these agreements as part of a process whereby we value the company or an interest in the company per the terms of the agreement.

Technology companies can often have disputes over buy‐sell agreements for a number of reasons, including:

- There are a growing number of companies with new ones being founded daily.

- A number are backed by sophisticated investors such as traditional incumbents (banks, asset managers, insurance companies) and private equity or venture funds and have experienced a number of funding rounds. We have previously noted that a number of venture and private equity investors often have specific agreements related to their investments that offer unique preferences and/or liquidation rights.

- A number of companies are very valuable, which leads to greater dollars to distribute, which is ultimately of concern to shareholders and makes the stakes relatively high if disputes arise.

Most owners and founders are so focused on running their businesses that they don't like to think about reviewing their buy–sell agreement, but spending some time on this can be very valuable and fixing issues on the front‐end can often be fairly inexpensive and painless. Once the agreement becomes triggered, however, it becomes expensive and time‐consuming to resolve potential issues. Buy–sell agreements are often unclear as they pertain to valuation. A poorly constructed buy–sell agreement can lead to expensive fees to resolve a dispute. We have helped clients structure buy–sell agreements, do annual (or sometimes more frequent) valuation analyses to set transaction pricing for buy–sell agreements, and offer dispute resolution services when things go awry.

As a founder/owner, take a moment and pull out your shareholder or buy–sell agreement and read it. Is it perfectly clear what will happen if a triggering event occurs (say another large owner/shareholder dies, gets divorced, or has a corporate split with the other owners/investors)? Can you tell how the interest will be valued? Do you know roughly what the value will be? Can you identify who the buyer of the interest will be and do you know how that buyer will fund the purchase?

When reviewing your buy–sell agreement (or developing one for those who do not yet have one), we have listed some important items to review in order to ensure that the buy–sell agreement sets reasonable expectations for the value of the company.

- The Buy–Sell Agreement Should Clearly Define the Standard of Value. The standard of value is an important element of the context of a given valuation, as it often defines the perspective in which a valuation is taking place. Similar to how a public stock analyst or investor might compare what they think a stock is worth to its trading price, valuation analysts are often looking at a company's value according to standards of value, such as fair market value or fair value. The most common standard of value is fair market value, which is typical for tax‐related valuation issues. Fair market value has been defined by the IRS and in a number of court cases. It is defined in the International Glossary of Business Valuation Terms as:

The price, expressed in terms of cash equivalents, at which property would change hands between a hypothetical willing/able buyer and a hypothetical willing/able seller, acting at arms' length in an open and unrestricted market, when neither is under compulsion to buy or sell and when both have reasonable knowledge of the relevant facts.4

The standard of value is so important that it is worth naming, quoting, and citing which definition is applicable. Without naming the standard of value, significant questions can arise in a dispute that could materially impact valuation. For example, fair value—which is often considered to be similar to fair market value—can have a number of different interpretations, ranging from different definitions of statutory fair value depending upon legal jurisdiction to the standard of value cited under Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). For most buy–sell agreements, we recommend one of the more common definitions of fair market value, as there is a long history of interpretation of this standard in the courts as well as professional writing on the subject.

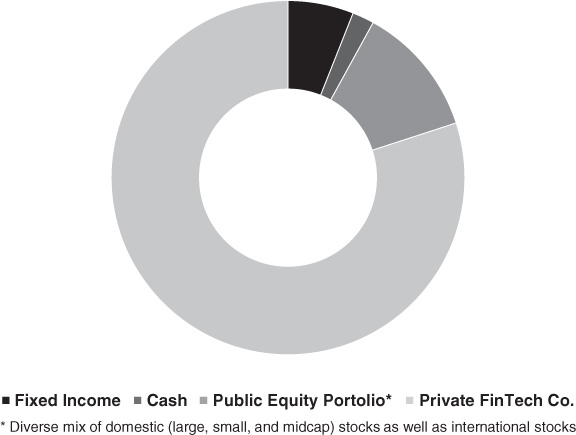

The buy–sell agreement should also blatantly clarify the level of value (Figure 12.2). Public stock market investors do not often have to consider what the appropriate level of value is. However, interests in private FinTech companies and banks typically do not have active markets trading their stocks and a number of FinTech companies are venture‐backed, which can often result in different share classes, rights, and preferences associated with investors in different funding rounds. Thus, a given interest might be worth less than the pro‐rata portion of the overall enterprise or the headline valuation number reported in the press based on the last funding round.

Appraisers and valuation specialists would likely attribute a portion of that difference in value to a lack of marketability.

Sellers typically want to be the bought‐out pursuant to a buy–sell agreement at their pro‐rata enterprise value (i.e., excluding consideration of the discount for marketability), but buyers may want to purchase at a discount. Unless the agreement is specific as to treatment of the level of value, the desire of the parties is typically secondary to what is actually laid out in the buy–sell agreement.

Fairness is also a consideration here. If a transaction occurs at a premium or discount to the pro‐rata portion of the enterprise value, then there are typically winners or losers to the transaction. This may be appropriate in certain situations, but typically, the owners of banks and FinTech companies are joined together at arms' length and want to be paid based on their pro‐rata ownership of the enterprise. The agreement, however, should be clear in terms of level of value. We often recommend including the level of value chart in Figure 12.2 and having an arrow pointing to the appropriate one in the buy–sell agreement.

- The “As‐of Date” for the Valuation Should Also Be Specified. While this may seem obvious, the particular date of the valuation matters. Market conditions and company‐specific events can change quickly over time and the date that the company is valued can have a significant impact on value. Furthermore, there is often disagreement as to whether the triggering event (and its potential impact on the company) should be considered in the valuation absent a specific instruction in regard to the valuation date. For example, if a “business divorce” is occurring or a significant founder passes away, should the valuation consider the potential impact on operations from that event (which may lower the valuation) or be valued on the day prior to the event occurring? While we will not go into all the details as to why selecting the valuation date is important, this provides just one example of how it can be important.

- Appraiser Qualifications and the Selection Process Should Be Specified. The appraisal community tends to include appraisers that fall into one of the following camps: “valuation experts” or “industry experts.” Valuation experts typically have appropriate professional training, designations, and a scholarly understanding of valuation standards and concepts. Additionally, they tend to have experience advising and valuing private companies, which is different from working for public companies. This includes valuing minority interests appropriately, understanding buy–sell agreements and their implications, and explaining work in litigated matters. By contrast, FinTech industry experts are often known for their depth of particular industry knowledge and perspective on the market of typical buyers/investors and sellers. Additionally, they tend to have transactions experience and regularly provide specialized advisory services to the FinTech industry. While there are pros and cons to each type of valuation professional, it is often best to specify that the valuation provider have a combination of both industry and valuation expertise. Ultimately, you need a reasonable appraisal work product that can withstand scrutiny from all parties and potentially judicial scrutiny.

FIGURE 12.2 Levels of Value

Source: Mercer Capital

Buy–Sell Agreement Example

Consider the following example. Assume a FinTech company is worth (has an enterprise value of) $30 million. There are three shareholders: the two founders—Tim and Richard—and a venture capital firm called NewTech Ventures. The two founders and NewTech each own one‐third of the company. As such, the pro‐rata interest of each shareholder is $10 million. If Tim and NewTech are able to force out Richard at a discounted value (let's say, $8 million, or a 20% discount to pro‐rata enterprise value), and finance the action with debt, what remains is an enterprise worth $22 million (net of debt). Both Tim and NewTech now own 50 percent of the company and their interest is now worth $11 million ($22 million × 0.5). This $2 million decrement to value suffered by Richard is a benefit to Tim and NewTech Ventures.

This example illustrates why structuring a buy–sell agreement properly is important and also why these matters often get litigated as certain shareholders can attempt to enrich themselves at the expense of other investors.

So when you look at your buy–sell agreement or attempt to formulate one for your company, consider this question: “Does my buy–sell agreement create winners and losers?” If so, who are they? Is that appropriate and acknowledged by all parties? Should the pricing mechanism in the buy–sell agreement consider discounts and premiums or rely solely on the pro‐rata proportion of the enterprise?

When crafting the buy–sell agreement, it is often unknown who will be exiting and who will be continuing. Thus, it is difficult to tell who will benefit or lose out in a transaction triggered under the agreement. It is still important, however, to think through the issue in advance and understand the implications so that the continuity of the business can be preserved and expensive ownership rifts can be avoided. There may be a compelling reason for the buy–sell agreement to have a pricing mechanism that discounts shares redeemed from departing shareholders as this may reduce the burden on the firm of remaining partners and promote firm continuity. As for buying out shareholders at a premium, the only argument for “paying too much” is to provide a windfall to former shareholders, which is hard to defend operationally.

Ownership tends to work best when it is structured in a way that supports the firm's operations and this certainly applies to the mechanics of a buy–sell agreement. It is often advised to attempt to avoid surprises to ensure the continuity of the company and avoid distractions. We often recommend to clients to keep the language in the buy–sell agreements up to date and also have a pricing mechanism that encourages annual valuations to be performed. If ownership sees consistently prepared appraisals over the years, then the ownership group will know what to expect should the agreement be triggered. They will know who will provide the valuation, what information will be analyzed, and how the valuation process as a whole will be constructed. While this will not eliminate the potential for disagreements over valuation, it can go a long way toward narrowing the difference of opinion and allow constructive feedback on the valuation methods and process over the years. Furthermore, this allows the board and management to measure valuation creation over time (by comparing the concluded values at different periods) and also serves to manage the expectations of owners as they will have a better idea of what price to expect in the event that they exit per the terms of the buy–sell agreement.

CONCLUSION

For those who are able to build a successful FinTech company or offering, this chapter provides insights into the process of determining the appropriate course of action once the company has matured and successful revenue generation has been achieved, which can often be as daunting as building the company itself. In prior chapters, we discussed acquisitions and partnerships with FinTech companies, but this chapter focused on strategic options for FinTech companies going a different route other than a third‐party sale to a financial or strategic buyer. Additionally, the discussion of buy–sell agreements provides important tips that can be utilized by both FinTech companies and bankers to ensure that their companies are built to last. Poorly thought‐out and improperly constructed buy–sell agreements can significantly limit a company's strategic and liquidity options.