The Skills You Will Need for Tomorrow’s High-Skill Careers

The world no longer cares how much you know; the world cares about what you can do with what you know. “To succeed in the 21st-century economy, students must learn to analyze and solve problems, collaborate, persevere, take calculated risks, and learn from failure.”

—Tony Wagner

Harvard University Innovation Lab, Expert in Residence

Key Points

• New jobs require new skills—not as an alternative to, but in addition to the skills of the past.

• High-level information, media, IT, statistical, and entrepreneurial skills will be required in virtually all high- and mid-skill jobs.

• You can gain the greatest differentiation and rewards from critical thinking, complex problem solving, creativity, innovation, and complex communication skills.

• Even more important than skills are key personality traits including initiative, self-direction, flexibility, adaptability, a passion for continuous learning, self-restraint, and especially “grit.”

• Most important is your ability to apply these skills and traits to real-world needs.

• One big problem; today’s schools aren’t really teaching many of these skills. You have to develop them on your own.

As the U.S. economy progressed through three very different eras (beginning as an agricultural economy, transforming into an industrial economy and then into an information or knowledge economy), employers looked for employees with different sets of skills and different types and levels of education.

• The agricultural economy, which calls for hard work in fields, primarily required physical strength, persistence, and adaptability to the whims of nature.

• The industrial economy, which basically required the ability to repeatedly follow defined rules, needed the “Three Rs” (reading, writing, and rithmatic), which helped spawn the move toward compulsory primary and secondary education.

• The information economy, which required the discretionary application of domain knowledge, was enabled by the growth of colleges and the post-WWII GI Bill, which helped millions of veterans get a college education.

The current economy is racing into a new era which some call the Creative Economy. It requires a change from the ability to manipulate information to the ability to manipulate abstract concepts and to create new types of knowledge.

As with the previous transformations, this one too will be very difficult: it will eliminate many jobs, transform many others, and create a number of totally new ones. The transition to this new economy will challenge those workers who are not prepared. It will, however, also richly reward those who understand how to deliver high levels of value. This value will come primarily in the form of identifying and finding innovative ways to address new needs; solving (or ideally, anticipating and preventing) difficult problems; and from effectively communicating and persuading others of the value of new ideas.

But just as the skills required for success in the information economy were built upon a foundation of reading, writing, speaking, and computational skills, success in the new creative economy will require and build upon a foundation that includes these plus solid domain knowledge skills. Success, however, will also require additional, and in many cases very different, skills than were required in the Information era. It will require an additional type of value add.

Those who anticipate and have developed the skills required for these new jobs will find themselves in great demand. Those who are not prepared will, as those who were left behind in previous shifts discovered, struggle to get and keep a job, much less build rewarding careers.

Herein lays one of your greatest challenges. The jobs created by this economy are emerging and changing much more rapidly than are the schools that are intended to educate people for these jobs. After all, most schools are still struggling to catch up with teaching the skills required for success in the information economy.

This, however, will not excuse you from the need to develop the skills. You will have to take responsibility for developing many of these skills yourself.

Skills of the Past Versus Skills of the Future

The future, as discussed in Chapter 2, will belong to those who can use high-end skills to create high levels of value. But what exactly are the high-value skills of the future? What separates them from the lower value skills that are still necessary, but are no longer sufficient foundations on which to build a high-value career?

MIT economists David Autor, Frank Levy, and Richard Murnane1 approached this question by segmenting current jobs into five broad categories on the basis of the skills and education required to perform the primary tasks of each:

• Routine cognitive: Mental tasks that are well-defined by deductive or inductive rules. Examples include dealing with simple customer service questions, many kinds of administrative tasks, or formulaic tasks such as evaluating applications for mortgages.

• Nonroutine cognitive or expert thinking: Solving problems for which there are no rule-based solutions. Examples include the practice of law and medicine, scientific research, architecting software, managing complex organizations, as well as some nonprofessional careers such as diagnosing tough auto repair problems.

• Routine manual: Physical tasks that can be described through the use of deductive or inductive rules. Examples include traditional assembly line jobs or the counting and packaging of pills into containers.

• Non-routine manual: Physical tasks that cannot be well described by a predefined set of If-Then-Do rules or that require optical recognition and fine muscle control. Examples include driving a truck or taxi, cleaning a building, gardening, or serving as a healthcare aide.

• Complex communication: Interacting with humans to acquire information, to explain it, or to persuade others of its implications for action. Examples include a manager motivating the people whose work she supervises (or especially an individual who brings a team of peers to consensus and action), a designer gauging a client’s taste and recommending furniture and furnishing that expresses that taste, a teacher explaining high-school-level concepts to a third-grade student, or an engineer describing why a new design for a microprocessor is an advance over previous designs.

Autor and Acemoglu, along with a number of their MIT and Harvard colleagues (including Frank Levy, Richard Murnane, Erik Brynjolfsson, and Andrew McAfee) have examined the future of jobs based on these tasks from a number of different perspectives. They looked particularly at the ways in which technology (and to a lesser extent offshoring) will transform these jobs. Some of the most instructive of these authors’ publications include:

• Autor, Levy, and Murnane’s 2003 The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change;2

• Levy and Murnane’s 2005/2006 How Computerized Work and Globalization Shape Human Skill Demands;3

• Autor’s 2010 The Polarization of Job Opportunities in the U.S. Labor Market.4

• Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee’s book, The Second Machine Age.5

Although I have discussed much of this research in a series of blog posts that I wrote in October 20116 and November 2011,7 and mention it through this chapter, many of their findings provide context for a number of changes we are already seeing in the labor force and the types of skills that will be required to get and excel at a job in the future. For example:

• Routine manual and cognitive tasks will be the primary victims of automation and globalization. Routine cognitive tasks (which can be accomplished by applying defined rules) and routine manual tasks (that can be defined in terms of a specific set of movements) are most subject to outsourcing and computerization. Jobs based on these tasks will increasingly disappear, first in the United States and other high-wage countries, and increasingly in lower wage countries. Many of those that remain will provide little job security and will be subject to intense price pressures. Many of these will be transformed into nonroutine manual or cognitive jobs.

• Nonroutine manual tasks are less subject to these trends. And since most of these services are site-specific, they cannot be readily outsourced. Most of these jobs, however, can be performed by people with relatively modest degrees of education and training and do not require particularly high levels of strength, stamina, or hand–eye coordination. They, like those for routine tasks, will be subject to much competition and will provide lower salaries and, often, less job security than in the past. This being said, some of these nonroutine tasks do require special training and skills, and produce particularly high-value results—think, for example, of particularly innovative gem cutters, artists, professional performers, or athletes. The relative handful of people who qualify for such jobs will continue to enjoy high levels of differentiation and will often be able to command high salaries. Indeed, globalization and the rapid growth of middle class consumers in developing countries has the potential of increasing the demand and compensation for such services and, in some cases, of creating globally branded superstars.

• Nonroutine cognitive tasks and complex communication, meanwhile, are less subject to (albeit, as discussed later, not fully protected from) offshoring and automation. However, as discussed in Chapter 2, technology will absolutely affect and increasingly transform these tasks. Those workers who best understand how to use technology to enhance the value they can deliver to their employers, clients, and customers will be among the biggest winners in this new era. So too will be those who use nonroutine cognitive and complex communication skills to create and promote this technology.

High-order cognitive or expert thinking skills will be instrumental in jobs that require people to address problems for which “the rules are not yet known.” These problems, according to MIT’s Irving Wladawsky-Berger,8 are of two broad types: Those for which

• The information is hard to represent in a form that computers can use, such as feelings or impressions derived from viewing body language; and

• Rules are difficult to articulate. This can include “complex processes” (such as those required to learn to ride a two-wheel bicycle), “pattern recognition” (the solving of problems that cannot be expressed in deductive or inductive rules), “divergent thinking” (as in starting from existing knowledge to ask new questions and develop new concepts), and the ability to exercise “good judgment” in the face of uncertainty.

Complex communication also includes a broad range of capabilities. At the most basic, it entails the ability to describe (in speaking and/or writing) complex phenomena and patterns in ways in which people can understand, the ability to ask questions in ways that elicit enlightening answers and prompt people to think of issues in new ways, and the ability to listen to or read and comprehend concepts. At a higher level, it involves interaction (simultaneously communicating, receiving, and processing), empathy (as in understanding and addressing the feelings and motivations of others), and persuasion (especially in selling your ideas and motivating others to action).

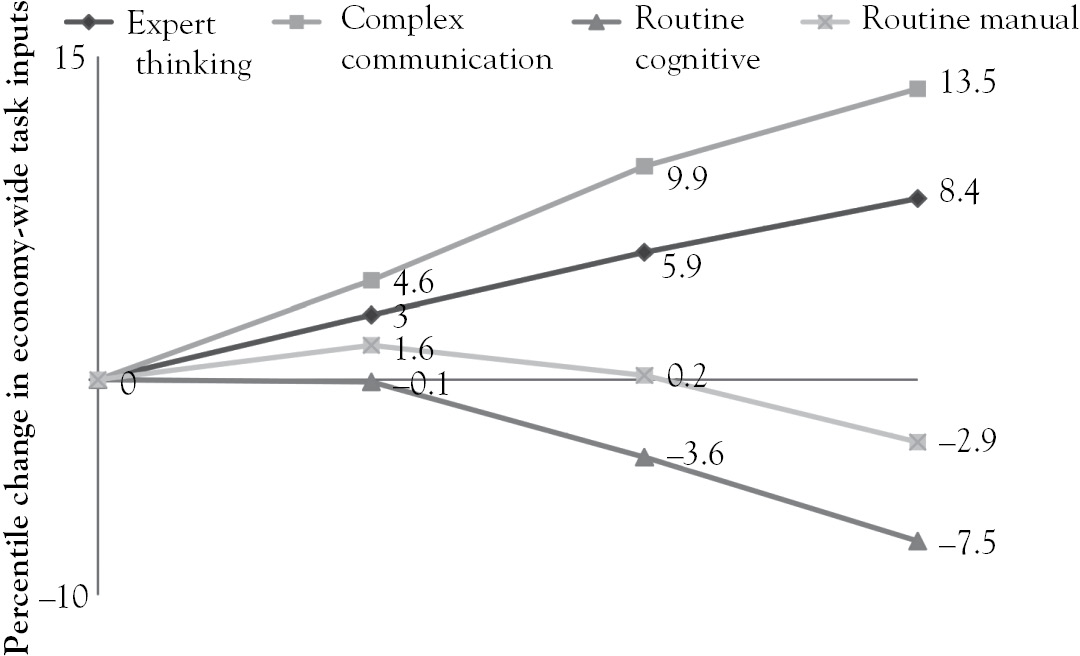

MIT’s Richard Murnane and Frank Levy summarize the changing demand for these skills in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1 Skill demands changing across the economy (1969–1998)

Source: Murnane (2008, February 29); Murnane and Levy (2004).

Now that you have a high-level understanding of the types of jobs that will and will not be sustainable, and that will allow you to differentiate and command premium wages for your services in the future (especially those based on nonroutine cognitive tasks and complex communication), let’s drill down into the broad range of knowledge and skills that you will need to prepare for these jobs.

New Skills for a New Era

The U.S. educational system generally recognizes the growing need for many of these higher level skills and is trying to determine how best to teach them (or more accurately, to help students “learn” skills that are inherently difficult to “teach”). A few organizations, meanwhile, have begun to delineate the types and levels of knowledge and skills that will be required for success in the Creative Economy, identify the type of curricula that will be most effective in helping students learn them, and develop the standards by which they can be measured. Two of the most important organizations doing this work are the:

• The Partnership for 21st Century Skills’ (P21) Framework for 21st Century Learning9 specifies the types of skills and content knowledge that will be required in the 21st century and the support systems that a student needs to learn them; and

• Common Core Standards specifies the skills, skill levels, and concepts (initially for math and English) that students should be expected to attain at each grade level.10

The P21 Framework provides a good starting point for delineating five key categories of skills that will be required in this new economy:

1. Core foundational subjects (English, reading or language arts, world languages, arts, mathematics, economics, science, geography, history, government, and civics) that students should master.

2. Interdisciplinary themes (global awareness, finance/economics/business, civics, health, and environment) around which these subjects can be taught to create literacy around current issues.

3. Information, media, and information technology skills;

4. Learning and innovation skills (critical thinking, problem solving, creativity, innovation, communication, and collaboration skills).

5. Life and career skills (flexibility and adaptability, initiative and self-direction, social and cross-cultural skills, productivity and accountability, and leadership and responsibility).

Although the subjects, themes, and skills shown in the first two levels of the P21 Framework list are still necessary prerequisites for most high-skill careers, they are no longer sufficient, especially if you hope to excel in the type of jobs that will allow you to differentiate yourself and add high levels of value in the Creative Economy. Information, media, and IT skills, for example, are now required for almost all such careers. The learning, innovation, and life and career skills mentioned in the fourth and fifth categories, meanwhile, will be critical in distinguishing the winners from the also-rans in the new Creative Economy.

Although the P21 Framework and the Common Core both recognize the importance of these higher level skills, it will likely take years or even decades before they percolate through the secondary educational system—assuming they are even accepted and enacted.

What about colleges where one may normally expect to learn such higher level skills? Which are the best schools for learning critical thinking and creativity? Adaptability? Initiative and leadership? In which major will you gain the deepest understanding of these skills and best learn to apply them? What degrees will best demonstrate your level of mastery of these skills?

Sure, you will be able to gain some of these skills through all levels of your education, not to speak of through your extracurricular activities, your work, and your life. But since these skills can be even more critical to your long-term success than the actual domain knowledge you develop, you can’t afford to leave them to chance. And since few schools or colleges explicitly focus on these skills, you must take charge of developing them yourself.

The first step is to understand what each of these skills actually entails and why they are so important in developing and succeeding in a career.

The Core Learning and Career Skills You Will Need to Succeed

The P21 list provides a great starting point. However, let me take some creative liberties in reorganizing and extending this list to suggest the very different roles each can play not only in preparing you for a job in the new economy but also in positioning you as one of the winners in this demanding new world. Let’s begin with what I see as the core skills: effectively the ante that will be required to even get a seat at the table. These “core skills” begin with three of P21’s sets of life and career skills (which are labeled as number five):

• Productivity and accountability: These include the ability to set and meet your own goals; plan, prioritize, and manage your work; and to be accountable for the results. The importance of these skills is, of course, a given.

• Leadership and responsibility: These skills are required whether you are the leader or are a member of a group since they include the ability to leverage the strengths of multiple people to achieve common goals and, when appropriate, lead others to your point of view and inspire action. They also entail the responsibility to advance the group’s goals, even if they may be at odds with your own—and the ability to step back and yield to others in the group, when appropriate.

• Social and cross-cultural skills: As collaboration becomes increasingly critical, the species of worker that just wants to lock themselves in their offices and do their work is on the verge of extinction in today’s business world. Even if you’re an introvert, you have to be able to work effectively with others. You have to know when and how to listen, be open to the ideas of others, and be able to express your own thoughts effectively and with respect. And in an age of diversity and globalization, you must also respect, understand the cultural nuances, and work effectively with people with whom you have little in common as well as those whose life choices you may totally disagree.

Two other types of core skills are bit different. Like the three previously mentioned life and career skills, they are so universally important as to be critical to virtually every high-skills career. But unlike those skills, they are in such demand and can produce so much value that you can effectively build entire careers around them. These include communication and collaboration skills (included in category 4 of P21’s list), as well as information, media, and information technology skills (category 3 of the list). My additions to this list are statistics and entrepreneurship. Why are these four skills so important in the jobs of tomorrow?

Communication and collaboration skills are not only core to success in all high-value (and many lower-value) careers, they can also provide foundations upon which you can build an entire career. Entertainers, journalists, novelists, and salespeople are effectively professional, full-time communicators. Although college professors play many roles, the growing importance of student reviews is placing a greater priority on their communication skills. Meanwhile, the growing popularity of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs, as discussed in Chapter 9 is already beginning to turn some professors, who are particularly gifted communicators, into new-age rock stars.

This being said, communication and collaboration skills also play somewhat more prosaic, but equally important roles in making or breaking many other careers:

• Communication is the ability to effectively use oral, written, and nonverbal communication and media to inform, instruct, motivate, and persuade others;

• Collaboration requires the flexibility and the ability to compromise and assume shared responsibility in diverse teams. These skills will be particularly important in an era of flexible, ad hoc, loosely bonded, and decentralized teams.

Both are instrumental in conveying information and concepts, working productively in teams, and persuading others of and in gaining support for your ideas and recommendations. They are also valuable in their own right, such as in your ability to sell yourself (or the products or the ideas you choose to represent) to employers, clients, and customers.

Two types of communications skills have the potential of being particularly important high-value differentiators:

• Complex communication, such as the ability to persuasively convey particularly complex ideas or relationships.

• Emotive communication, in which you can express subtle emotions with sensitivity and ideally empathy.

Although these skills are required in virtually any high-value career, particularly gifted communicators—especially those with high degrees of empathy and cultural awareness—will have huge advantages. Those with such skills are likely to have greater success in selling themselves and their ideas, in mobilizing people to action, and in being viewed and accepted as leaders.

Particularly gifted communicators are likely to have greater success in selling themselves and their ideas, in mobilizing people to action, and in being viewed and accepted as leaders.

Information, media, and information technology skills, as mentioned, are becoming fundamental to all types of high-skill work. One must, however, distinguish IT competence from IT fluency. IT competence, which allows you to use these resources in your own field, is a core requirement in virtually any profession. You must be able to effectively access, use, and critically evaluate information; effectively analyze, use, and create all types of media; and use technology to research, organize, evaluate, and communicate information.

Such skills are also becoming increasingly critical in building your own career—such as in communicating your brand and your value proposition and in building the type of network that you will need to get a job and advance your career.

Then there’s IT fluency. Those who are particularly skilled in these areas can have big advantages in the job market. Software engineers, information architects, and new-age media professionals can often command $50,000 to $100,000 salaries with a bachelor’s degree. Those with particular talent don’t even need degrees. Witness Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg. Some don’t even have to graduate high school. As discussed in Chapter 7, a growing number of software companies are luring particularly gifted undergraduates—and in some cases even high school students—out of high schools and colleges with six-figure offers.

Beyond the monetary rewards, people with deep IT skills have the potential of playing increasingly central roles in all types of industries and job functions. Some will become architects of the rapidly expanding information age. Others will develop the hardware, software, and services that will increasingly define our careers and our lives. Still others will help companies to use IT to achieve competitive advantage in their own industries. Millions of others will leverage their skills into creating their own companies.

People with deep IT skills have the potential of playing increasingly central roles in all types of industries and job functions.

Statistics is one of my own additions to this list. Although this is generally included in the core foundational skill of mathematics, statistical skills, like IT skills, are becoming so critical in day-to-day business (not to speak of in your personal life) as to require special focus.

But although everyone must have a working knowledge of basic statistics, deep statistical analysis skills will become particularly critical in the era of Big Data. This data will allow you to track and measure virtually anything. The real value comes from the ability to understand what the data is telling you and what it means for your job and your business. These deep statistical skills are becoming so important that graduates capable of analyzing and especially of identifying business opportunities from Big Data are, as discussed in Chapter 2, already becoming some of the most sought after and highly paid professionals.

Entrepreneurship is my other addition and already one of the biggest, most important trends in business, accounting for more than 14 million people (nine percent of the total U.S. workforce). Millions of people, whether they are looking to recover from a layoff, want to become their own boss, or have a burning desire to create the next billion-dollar company, are starting their companies. Sometimes this is by choice; often, especially during the recession, by necessity. While 25 to 30 percent of U.S. workers currently work as freelancers or contingent workers, an Intuit Corporation study estimates that this figure will exceed 40 percent by 2020.11

The need for entrepreneurial skills is not limited to those who have their own businesses. Companies are increasingly looking for internal entrepreneurs. They can range from those who are not only capable but also anxious to run their own projects, their own branches, or to establish and run an in-house skunkworks (an in-house, experimental, independent research organization) to pioneer the company’s next billion-dollar business.

Author and New York Times columnist Thomas Freidman goes further. As he explains in his March 2013 column, Need a Job? Invent It, while your parents were able to “find” jobs, you increasingly have to “invent” your own.12 This may mean going out on your own if you can’t find a position in an established company. It also means inventing a position within another company. Having done just this in the two companies for which I worked (before starting my own company), I completely agree.

While your parents were able to “find” jobs, you increasingly have to “invent” your own.

If you get a job in a company, you will inevitably find untapped opportunities: projects that were begun but not completed; or unexplored market opportunities—whether unidentified or identified. If you can demonstrate how your company can benefit from these–-and that you are the person that can make it happen—you may get a chance to invent your own job around your own interests and your own skills. Once you have gained experience and credibility within your organization, you may be able to go further: selling your idea to launch a new line of business or operation (again, around your own interests and skills). If you can sell the idea within your company, then presto—you’re an in-house entrepreneur. If not, you may choose to shop the idea (and of course yourself) to another company or start you own company around the idea.

Whatever the type of business, entrepreneurship requires skills: everything from understanding how to test ideas, raise money, market your product or service, manage your finances, build and promote your company’s brand, and dozens of others. These skills, and some of the many ways of learning them, are discussed in Chapter 9.

High-Value Skills on Which to Build Your Own Brand

Four P21’s skills, which are combined into two categories, are somewhat different. While they will be required for success in virtually all high-value careers, they also promise to provide some of the greatest opportunities for differentiation among those high-skill workers. Those with these skills are best positioned to be the winners, not to speak of the stars, of the Creative Economy. These skills are:

• Creativity and innovation and

• Critical thinking and complex problem solving

Although one would be hard-pressed to build a specific career around these skills (as you can with communication and IT skills), they are arguably even more important in determining your ultimate success in the new economy. Let’s look at each category.

Creativity and innovation are becoming much more than “nice-to-have” skills. They are rapidly becoming hallmarks of success in a 21st-century economy. These include the ability to look at old things in new ways, to recognize ideas or possibilities that others don’t, and to identify new ways of connecting dots that others see only as random or unrelated points.

Creativity and innovation are becoming much more than “nice-to-have” skills. They are rapidly becoming hallmarks of success in a 21st-century economy.

Creativity, such as in the form of art, may certainly be spontaneous and freeform. However, some of the most valuable forms of creativity—those that provide workable solutions to pressing problems or that identify innovative new business opportunities—seldom come as flashes from out of the blue. They entail much more than spouting off dozens of new top-of-the-head ideas. Creativity is often, as Einstein said of genius, more like “one percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration.” And, as Steve Jobs showed us by integrating right-brain artistic sensibilities into the left-brain world of computer and software development, some of the most creative solutions are likely to combine knowledge, principles, and methodologies across very different disciplines.

While creativity typically entails a lot of hard work, innovation requires even more. Innovation, which is often based on creative ideas, requires the actual implementation of these ideas. This may entail the overcoming of all types of real-world obstacles and organizational resistance. It can require persuading people to embrace something new and increasingly, in today’s IT-based Internet era, disciplined system and software design. Not all innovations, however, require that you invent new products or create original works of art. Most of today’s innovations come from combining previously developed innovations in new ways (as by combining telephones and computers into smartphones) or building new layers atop an existing offering (such as paint on a canvas). Some of the highest-value innovations don’t require the creation of products at all. Companies including Federal Express and Amazon.com redefined entire industries by reconceiving established processes and creating new business models.

Creativity and innovation both often entail knowledge of—and the ability to create linkages among—multiple domains and the ability to assess issues based on methodologies from different disciplines. It also appears that people can be taught to apply creative thinking to intractable business problems.13

A growing number of schools, such as Stanford’s Institute of Design, MIT’s Media Lab, and the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, already offer programs intended to do just this. These so-called D-schools teach methodologies for looking at problems from new and different perspectives and for using different types of processes to come up with more creative solutions. A growing number of large, traditionally innovative companies, such as Procter & Gamble, Google, Nike, and Fidelity, are putting considerable stock in such efforts, hiring people from such programs, putting their own employees through them, and launching their own in-house design-thinking courses.

The opportunities for success of particularly creative and innovative people are patently obvious. Artists, musicians, and performers, often viewed as the embodiment of creativity, have the potential (although not necessarily the likelihood) of gaining huge rewards—not just in terms of money but also in fame and the ability to define and control their own careers.

Creativity and innovation, as discussed, however, go far beyond the arts. Think of Albert Einstein, Thomas Edison, Fred Smith (the founder of Federal Express), or Howard Schultz (Starbucks’ founder). These people had the creativity to identify business opportunities that nobody had previously dreamed of (not to speak of the perseverance required to succeed), and built iconic companies in the process. And then, of course, there’s Steve Jobs.

Not everybody has the creativity to create a new artistic movement or to identify a business opportunity that will change the world, or even redefine the culture of drinking coffee. Nor does creativity necessarily require huge, unprecedented leaps of imagination. Incremental innovation—the ability to identify small, useful changes to an existing idea, product, or process—can also create incredible value. It can also be incredibly rewarding.

It will also be an increasingly important requirement for success in the 21st-centrury economy. In fact, Richard Florida argues in his book, The Rise of the Creative Class Revisited, that creativity is becoming the defining characteristic of an entire class of professionals whose services will be in greatest demand and will command the largest wage premiums.14

Critical thinking and problem solving skills entail the ability to reason and make sound judgments within a broad, systems framework. In some sense, these are a superset of analytical skills. But while analytical skills used to be the foundation of many of the middle-income, white collar jobs of the past, many of these jobs can be done more efficiently, and sometimes even better, by lower-priced offshore professionals or increasingly by software.

Critical thinking and problem solving go much further. They require the ability to:

• Conceptualize a problem;

• Pull together and systematically examine a broad range of seemingly random data;

• Filter out the irrelevant or misleading;

• Use a combination of structured and unstructured inquiry to identify underlying patterns;

• Identify and systematically evaluate multiple hypotheses with an open mind; and to

• Apply these patterns to different situations and problems.

One of the most critical and valuable components is the ability to identify and ask the right questions—questions that other people do not see; questions that will prompt you and others to think about a familiar situation in different ways; questions that will lead to solutions. It isn’t surprising that a number of companies view the ability to ask perceptive questions as being even more important than actually solving a problem. They increasingly recognize, as did Einstein, that “the formulation of a problem is often more essential than its solution.”

A number of companies view the ability to ask perceptive questions as being even more important than actually solving a problem.

These skills can be applied to and provide value in any discipline, regardless of how specialized or how broad. But, in this age of hyperspecialization, generalists with these skills can provide particular value by helping teams reimagine problems by looking at them in a new light and by helping to draw upon other domains for innovative solutions. In fact, some of the most effective teams are those that combine generalists with specialists from different fields.

Universal Personality Traits You Will Need

Whether you call them personality traits, attributes, attitudes, life skills, or virtually anything else , they may be the most important of all the skills discussed in this chapter. These traits, particularly when applied in conjunction with combinations of the previously mentioned skills, or with core subjects or disciplines, often spell the difference between success and failure. You must have both the skills to conceive value and the traits to actually deliver this value if you hope to succeed in this new world. P21 identifies these attributes or traits as:

• Initiative and self-direction; and

• Flexibility and adaptability.

I would add a few others:

• Insatiable curiosity and a passion for learning;

• Self-restraint, or the patience to wait for deferred gratification; and

• Entrepreneurship.

Let’s look at each in turn.

Initiative and self-direction go by many names, including motivation, focus, self-discipline, persistence, and grit. They entail the ability to set ambitious, yet (ideally) achievable long-term goals, to develop plans, and to prioritize your actions for achieving these goals—and to do all this independently, without having been told to do so, and without the need for oversight or coaxing. It requires that you manage your own efforts by allocating time and resources among multiple priorities, meeting (or ideally beating) deadlines, and of course, surpassing everybody’s (possibly even your own, much higher) expectations.

Taking initiative also means taking risks. Any time you stretch yourself beyond what you know, beyond your comfort zone, or beyond what you had previously imagined, you are taking a risk. Although you will certainly want to mitigate these risks (such as by applying to a safety school while planning for admission into Harvard), the taking of calculated risks is the only way of stretching yourself. Yes, you may fail. But as long as you have a plan for limiting or protecting yourself from disastrous consequences, failure is one of the best learning experiences. And, as long as you have the later-discussed flexibility and adaptability to learn from and recover from failure, you can often turn failure into an even greater success. Think, for example, of Silicon Valley, where failure in a previous attempt to launch a business is not just a badge of honor, it is also often an advantage in attempting to get funding for your next start-up. As leading-edge design firm IDEO tells its employees: “fail early and fail often.” Failing early, as they claim, allows you to succeed sooner.

Initiative is certainly one of the primary requirements for successfully building your own business, not to speak of for building your own career. It is also becoming increasingly important in working for others.

As Thomas Friedman explained in his October 22, 2012 New York Times op-ed piece The New Untouchables, gone are the days when you could advance in an organization by being a good and loyal soldier—by doing what you are told and staying out of trouble.15 As he explains, the people who received pink slips during the recent recession were “the average practitioners”—those people who perform routine tasks and those that wait for work to be handed to them. Friedman calls those people who are too valuable to layoff “the new untouchables”: those with “the ability to imagine new services, new opportunities, and new ways to recruit work.” These people have the “imagination….to invent smarter ways to do old jobs, energy-saving ways to provide new services, new ways to attract old customers, or new ways to combine existing technologies.”

Gone are the days when you could advance in an organization by being a good and loyal soldier—by doing what you are told and staying out of trouble.

Meanwhile, even if these new untouchables do get laid off (or more likely, if they voluntarily leave an unfulfilling or frustrating job), they are best positioned to get another job or to go out on their own or start a new company to realize their visions. This form of initiative ties directly into the “self-direction” part of the personality trait equation.

Self-direction is at least as important as initiative. It entails the ability to recognize the need for and areas in which you must extend your current skills and knowledge or develop new or complementary skills. And then, just as importantly, to take the initiative in ensuring that you develop them. It is also one of the most important components of a commitment to lifelong learning—one of the best forms of insurance you can have for preventing your own obsolescence.

Flexibility and adaptability: Adaptability, as defined by P21, entails the ability to work in a climate of ambiguity and changing priorities and to adapt to different roles and responsibilities and changes in schedule or context. The corollary skill of flexibility entails the ability to accept and effectively respond to feedback (positive and negative) and the willingness to balance diverse views. Not only are these skills among the most important in preparing for a career, they may, in an era where the only certainty is uncertainty, well be the most important.

In an era where the only certainty is uncertainty, flexibility and adaptability may well be the most important personality traits.

After all, while initiative and persistence are certainly among the most critical skills required for success in your career and your life, they can also be among the most dangerous. There is certainly great merit in the old maxim, “if at first you don’t succeed, try, try again.” But there is also wisdom in Albert Einstein’s definition of insanity: “doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.” Trying again does not mean doing the same thing over and over. It means, or at least it should mean, a continual process of adaptation: examining the source and reasons for a particular result, evaluating alternative approaches to solving the problem, and adjusting and readjusting your approach until either you succeed or you are forced to change your goal.

This adaptability is critical not only in broad objectives, such as in finding the job of your dreams or starting your own job. It is required in every aspect of your career (not to speak of your life). As Reid Hoffman and Ben Casnocha explain in their book, The Startup of You, your career must be in continuous “beta” (a software prerelease phase in which developers identify defects, and collect feedback and recommendations from prospective customers before developing the final version).16 You must continually reassess where you are going and how best to get there and engage in continuous experimentation. This adaptability must be incorporated directly in your career planning process, as well as in your job and in your life. After all, given the pace of change in today’s market, you can’t let your career planning get too far ahead of reality. As the book’s authors explain, it’s probably best to think two career steps in advance, not ten.

Let’s now look at my additions to P21’s list.

Insatiable curiosity and a passion for learning is a trait that, while always desirable and helpful, is becoming indispensable. The primary reasons: the pace of change has become so fast and unpredictable, and the body of human knowledge has become so large and specialized, that anyone who does not have this passion is destined to fall behind. Changes, no matter how sudden and dramatic, can often be discerned from (or at least suggested by) earlier clues. This can be anything from a war to the failure of a company, or the automation or outsourcing of a particular job. Although not all changes are telegraphed, those who understand what to look for and who continually look for clues have a better chance of anticipating, hedging, and preparing for them. Better yet, those who anticipate and position themselves ahead of emergent trends have the potential of getting in on the ground floor of new industries or companies.

The pace of change has become so fast and unpredictable, and the body of human knowledge has become so large and specialized, that anyone who does not have insatiable curiosity and a passion for learning is destined to fall behind.

Just as importantly, the state of human knowledge is expanding exponentially. Every field, regardless of how specialized or obscure, has hundreds, if not thousands of specialists whose lives are devoted to extending the boundaries of their fields. Some fields such as medical genetics are just emerging. Even mature fields such as financial trading and materials science are being continually revolutionized (such as by high-frequency trading and nanotechnology, respectively). You can’t escape progress. Any professional that does not keep up is destined to watch as they and their skills become obsolete. While it used to be that corporations could usually find a role for those who couldn’t or wouldn’t keep up, few now have the luxury of retaining dead wood.

Self-restraint, or the patience to wait for deferred gratification: Self-restraint can be a foreign concept in a society obsessed with instant gratification and living for the moment. It can also be a critical foundation in any effort to build a career, start a business, or even just succeed in a job.

A plan is, of course, the foundation for building a career plan. It entails determining what you want to accomplish sometime in the future, identifying the steps that are required to achieve your objective, and then taking those the steps (leavened with, of course, a big dose of flexibility and adaptability) required to achieve this goal.

The same is true of starting a business. Before you leave an established job (especially if you depend on that job to pay your rent) and commit your and your family’s savings to a new business idea, it’s probably a good idea to have a plan. You should at least have a vision for your business, have initial financing lined up, and have a pretty good idea as to your target market and means of reaching that market. Ideally, you may even have a prototype for a planned product and have initiated conversations with potential customers or investors. All plans, of course, must be subject to change, and you must have the flexibility and adaptability to change or even abandon your plan. But just as failure is a critical learning experience, so too is planning and the self-restraint it imposes upon you.

Just how important is this self-restraint? Two Yale professors just wrote a 2014 book, The Triple Package: How Three Unlikely Traits Explain the Rise and Fall of Cultural Groups in America, that attempted to determine why some minority U.S. immigrant and cultural groups (Jews, Mormons, Chinese, Indians, Iranians, and others) consistently outperform national norms.17 They boil their explanation down to a combination of three traits:

1. Insecurity, which results in a drive to continually prove oneself;

2. A superiority complex, or a belief in some form of their own exceptionality (and therefore abilities); and

3. Impulse control, which they believe may be the single most important.

Although the authors acknowledge that each of these is contrary to many contemporary American attitudes and sensibilities, they contend that this combination drives success not just of minorities, but any individual from any background.

Learning and Applying 21st-Century Skills

Although P21 has taken the most comprehensive approach for defining the skills required to succeed in the 21st century, and for identifying the type of learning environments and processes by which they can be learned, it is by no means the only effort to identifying the skills required for success.

Books from authors including Daniel Pink18 and Thomas Friedman19 and Harvard Graduate School of Education professors Howard Gardner20 and Tony Wagner21, for example, propose their own lists. Most such examples and lists, however, implicitly incorporate many of P21’s themes. Education provocateur and reformer Tony Wagner, for example, effectively foreshadowed P21’s work in his still provocative 2008 book, The Global Achievement Gap.22 This book highlighted seven types of skills:

1. Critical thinking and problem solving;

2. Collaboration and the ability to lead by influence;

3. Agility and adaptability;

4. Initiative and entrepreneurialism;

5. Effective oral and written communication;

6. Assessing and analyzing information; and

7. Curiosity and imagination.

Employers tend to agree with such requirements for success. According to a 2013 Hart Research survey, the six most important capabilities employers are looking for in graduates are: critical thinking and analytical reasoning; the ability to analyze and solve complex problems; oral and written communication; the ability to locate, organize, and evaluate information from multiple sources; and the ability to innovate and be creative.23

Dilbert cartoon creator Scott Adams, in his 2014 career guidance book How to Fail and Everything and Still Win Big, suggests a much more pragmatic list of everyday skills: public speaking, psychology, business writing, accounting, basic design, conversation, overcoming shyness, second language, golf, grammar, persuasion, hobby-level technology, and voice technique.24

But whatever the list, you still have to ensure that you not only learn but also continually apply, refine, and enhance these skills. After all, as Wagner explains in his most recent book, Creating Innovators: The Making of Young People Who Will Change the World, knowledge is now a commodity, available over the Internet.25 “The world,” he claims, “no longer cares how much you know; the world cares about what you can do with what you know.” “To succeed in the 21st-century economy, students must learn to analyze and solve problems, collaborate, persevere, take calculated risks, and learn from failure.”

The world no longer cares how much you know; the world cares about what you can do with what you know.” “To succeed in the 21st-century economy, students must learn to analyze and solve problems, collaborate, persevere, take calculated risks, and learn from failure.”

But exactly how do you apply these skills to developing your career?

It’s true that a small percentage of people—those with truly exceptional skills in a particular area, such as analytical skills and/or with exceptional understanding of particularly important areas—will continue to be sought after, retained, and rewarded for their analytical skills alone. The vast majority of us, however, need to combine multiple skills. You must, for example, have:

• The imagination to identify new opportunities;

• The skills to build compelling business cases around them;

• The interpersonal and communication skills required to sell these ideas;

• The determination to achieve your goals, regardless of the obstacles you face; and

• The adaptability to continually reassess progress, search out and incorporate new evidence into your evaluations, and continually tune and adapt your goals and your approaches to achieving them.

But if these traits and skills are so important, why aren’t schools organized to teach them? Why haven’t they created academic curricula, or even formal courses around them? Although P21 and the Common Core Initiative hope they will do exactly this, the current opportunities for learning most of these skills are, at best, scattered.

You can certainly take courses in which some of these skills are taught, such as communications or information technology. And plenty of classes and books claim to teach productivity, culture sensitivity, and creativity. Creativity and innovation, as discussed above, are becoming some of the most sought-after and in-demand disciplines in schools such as the Stanford D-School and the MIT Media Lab. Then of course, there are the proliferation of courses and programs in entrepreneurship, such as those identified in Chapter 9.

But what school, book, or seminar can teach you initiative or accountability? Or can they be taught at all? Perhaps some skills and some personality traits can only be learned by experience and by trial and error.

Until the educational system acknowledges the importance of such skills and develops an agreed upon process for helping you learn them, you will have to take responsibility for learning them yourself. Luckily, however, life is filled with opportunities for developing and practicing these and all types of other skills. However, you have to search out and take advantage of these opportunities—and make sure that you learn the appropriate lessons from them. Plus, learning these skills yourself provides you with a number of advantages. First, you can do so by focusing on opportunities in which you have an interest and are motivated to explore, rather than having someone assign them to you. Second, you can learn these lessons in whatever way is best suited to your own learning style, rather than the way someone decides they should be taught.

Until the educational system acknowledges the importance of such skills and develops an agreed upon process for helping you learn them, you will have to take responsibility for learning them yourself.

Sure this will take work and may result in many mistakes along the way. That, however, is probably all for the best since the very process will help you learn other skills, such as initiative, self-direction, accountability, and flexibility. Taking responsibility for this part of your education will also give you good practice for many of the other things you will have to do in building and managing your career. For example, they will be good practice for what you will have to do to identify and create your own brand, for building and managing your own network, and for designing and managing your own education.

Lifetime Skills Development

Developing these skills, graduating from school, and getting a job are only the first steps in building your career. Keeping the job—not to speak of succeeding in it and using it as a springboard to building a successful lifelong career (much less building two or more different careers)—requires far more than in the past.

As discussed throughout this chapter, the skills required to get and succeed in a job in today’s concept-driven creative economy are very different from those required for jobs in the information-based knowledge-based economy. Just as important, the jobs in this new economy will change at a much faster rate than had been the case in previous economies.

Rapid change is uncomfortable. It presents you with a critical choice: you can either:

• Live by the skills you developed in school, and risk career stagnation and possible obsolescence; or

• Anticipate how jobs and skill requirements will change and develop these new skills in advance, thereby positioning yourself for promotions and, especially, for the jobs of the future—including those in entirely new disciplines and industries.

This later course will require lifetime education. This education can be formal or informal, depending on the skills you wish to enhance or develop, the learning style that is most effective for you, whether or not you need some form of certificate to demonstrate your skills, and your own schedule and budget. It may come simply from reading, participating in clubs or groups, or from pursuing a hobby. More likely, it will include at least some more formal components. It can entail the taking of a few additional college or graduate classes, completion of a MOOC course or program or even a new degree. Or perhaps your employer will offer and pay for courses.

Whichever approach you choose those who hope to grow, or at least to remain fresh in their careers, have no alternative. They must continue their education. And now, with the proliferation of free information across the Internet and the availability of free MOOC-based college-level courses that can be completed at any time and from any location, you also have no excuse for not doing so.