Steps 10 Through 12

Education is what remains after one has forgotten what one has learned in school.

—Albert Einstein

Key Points

• College grads on average have more fulfilling, enriching, and stable careers than those without degrees.

• Occupations that require an advanced degree are growing faster than jobs with lesser educational requirements.

• Although a four-year degree is the most common and socially accepted path to a fulfilling and enriching job, it is not the only path and isn’t well-suited to all.

• There is serious question whether college is fulfilling its core missions and especially if the costs outweigh the benefits.

• There are more credible options to college than ever before.

• One of the worse reasons to go to colleges is that you’re expected to do so.

You now know the types of jobs that are likely to offer the best career opportunities (Chapter 2 and the broad range of skills that will be required for success in today’s Creative Economy (Chapter 3. You have assessed your own passions, interests, and skills (Chapter 5 and have developed an initial idea of the types of jobs and careers that are best suited to them (as well as their employment prospects, skill and credential requirements, potential salaries, and their long-term growth potential) (Chapter 6. You now need a plan that will not only ensure that you have the qualifications to prepare you for entry into your chosen field but that will also:

• Differentiate and provide you with an advantage over other candidates for landing your first—and ideally your first few—dream jobs; and

• Prepare you for long-term success, not just in your first few jobs, but through your entire career (in whatever field that career may turn out to be) and in your life outside of work.

This is a complex task which is complicated by the fact that your educational opportunities are exploding. In the “old days,” you learned the requirements for most careers by learning, either formally (as through an apprenticeship program) or informally (as by being thrown into a new position or by working under or with people with more experience). The career preparation process changed with the creation of formal primary and secondary schools and curricula and, especially, with the creation of colleges and graduate schools.

There are now literally hundreds of different types of college and graduate programs. Some schools, such as community colleges, many for-profit schools, and boot camps, combine elements of classroom education and apprenticeship-like training. Community college educations, meanwhile, can blend into four-year college degrees and new types of education, such as Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) and Gap Year programs, can be used as part of or substitute for any of these more formal educational programs.

Given all the options and the blurring of distinctions among them, it’s not possible to examine the education section of the plan (Steps 10 to 14) sequentially. I am, therefore, dividing the examination of educational issues across three chapters, aligned generally by type of institution and program and the complementary and competing ways in which you can use each to achieve your goals.

• This chapter focuses broadly on the growing debate surrounding the role and value of a college education and the growing number of alternatives to a four-year degree;

• Chapter 8 is for those who have chosen or are considering a four-year college or university, looking at the considerations of choosing a school; majors, minors, and other courses; and graduate school. It also looks into some of the broader issues surrounding a college education, such as the tradeoffs between preparing for a job and developing broader life and career skills; the tradeoffs among academics, social life, extracurricular activities, and internships; and the increasingly critical issue of the cost of a college education, who can afford it, and how to assess the value of your degree.

• Chapter 9 examines the exploding range of options to a four-year degree. It begins with community colleges (and the multiple roles they play) and how they blend with and compete with apprenticeships; the growing range of structured, semistructured, and unstructured options to college; and different means of supplementing a college degree with more career-focused programs.

Thinking about Your Education Options

College is certainly the most common, the most socially sanctioned, and the most employer-recognized path to preparing for a high-skill occupation. And, in an era in which the nature of jobs is changing so quickly, college has become one of the most trusted indicators that you have the core knowledge, skills, and persistence required to do the job for which you are being hired. Just as importantly, in a slow growth market in which employers have a choice of many applicants for each job, many are demonstrating a strong preference for a college grad, even for jobs that do not actually require a college degree.

This being said, college is not the only path to a rewarding, high-skill, high-value career. Many good jobs don’t require college. Different careers require very different types and amounts of education and training—ranging from effectively zero to eight or more years of formal postsecondary education, plus multiple years of on-the-job training. (See the Bureau of Labor Statistics [BLS] Education and Training Assignment site for an overview of these requirements for different occupations.)1

Nor may college be the best path for you. College, after all, is just one means of gaining the knowledge, developing the skills, and creating the network you will need for your career. As discussed later, many people with more than enough intelligence and persistence to succeed in college are better suited to much less formal, much more personalized learning environments.

Although a four-year college degree is the most common and most widely recognized path to preparing for a high-value career, it is not the only one. And it may not be the best one for you, your particular needs or for the type of job you are targeting.

This being said, college, or some other form of disciplined higher education (whether formal or informal and self-directed), will be one of the primary means by which most young adults will develop not only the qualifications but also the certifications that employers will look for in new employees. This education will also form the foundation for the type of self-directed analysis, critical and innovative thinking, communication, and life skills that you will need in all aspects of your life, as well as in your career.

While Chapters 8 and 9 look specifically at the advantages, limitations, and roles of various types of postsecondary education, this chapter looks broadly at the roles of various types of education in preparing you for the jobs of the future, the relative advantages and limitations of each, and provides a means of thinking about the type of education that may be best for you.

The College Advantage

College graduates, as I have discussed throughout this book, are still having a tough time finding jobs that make use of their education. Although larger percentages of graduates are now getting jobs than during and immediately after the recession, many of these jobs neither require degrees nor pay the salaries or provide the training or advancement opportunities of those that do require degrees. But if you think it’s tough for college grads, consider the plight of those who don’t earn college degrees.

College grads (and especially advanced degree holders) are far more likely to earn more money and are far less likely to experience unemployment at some time during their careers. For example:

• Ninety-four of the BLS’s Top 100 paying occupations2 require a four-year degree or higher;

• Pay for college graduates has risen 15.7 percent over the past 32 years (after adjustment for inflation),3 while income of workers without college degrees has declined by 25.7 percent:

• Lifetime earnings of high school graduates average about $973,000 in 2009 dollars, compared with $3.6 million for those with professional degrees (associate and bachelor’s degree holders fall in between, at about $1.7 million and $2.3 million, respectively).4

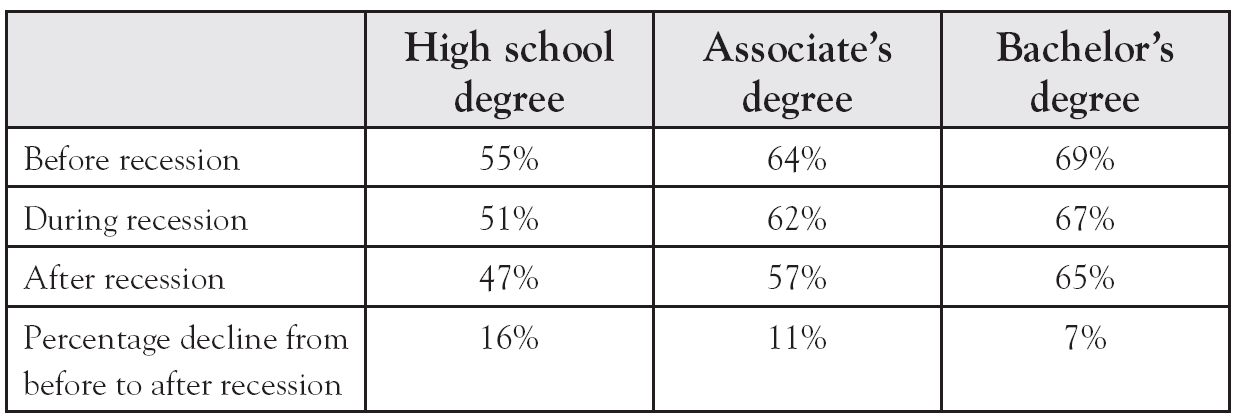

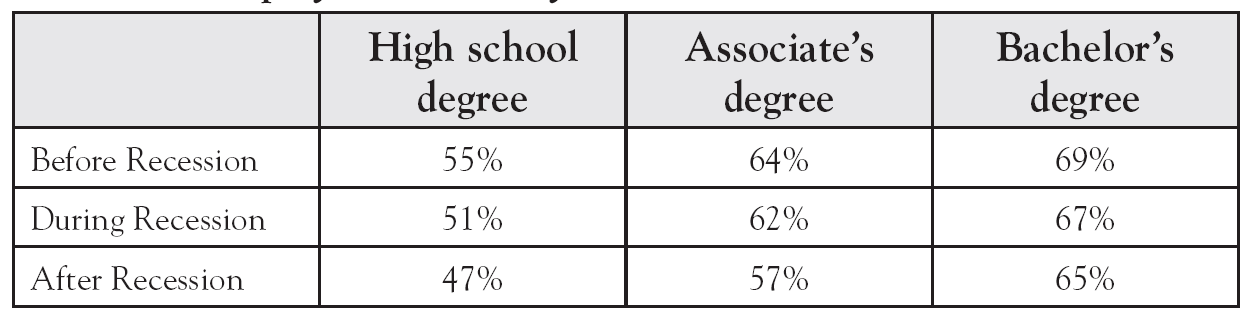

These disparities aren’t new. However, they are becoming much more pronounced, especially during and in the aftermath of recessions. As shown in Table 7.1, those adults with higher levels of education enjoy higher rates of employment than do those with less education, regardless of the state of the economy. Just as importantly, these employment rates tend to fall much more slowly for those with higher levels of education during and after a recession than for those with less education. In fact, the last recession saw the employment rate for high school educated individuals fall more than twice as much as for those with bachelor degrees.

Table 7.1 Employment rates by education level: 2007–2012

Source: Adapted from “How Much Protection Does a College Degree Afford?” (2013), Figure 2, p. 11. http://www.pewstates.org/uploadedFiles/PCS_Assets/2013/Pew_college_grads_recession_report.pdf (Figure 2, page 11)

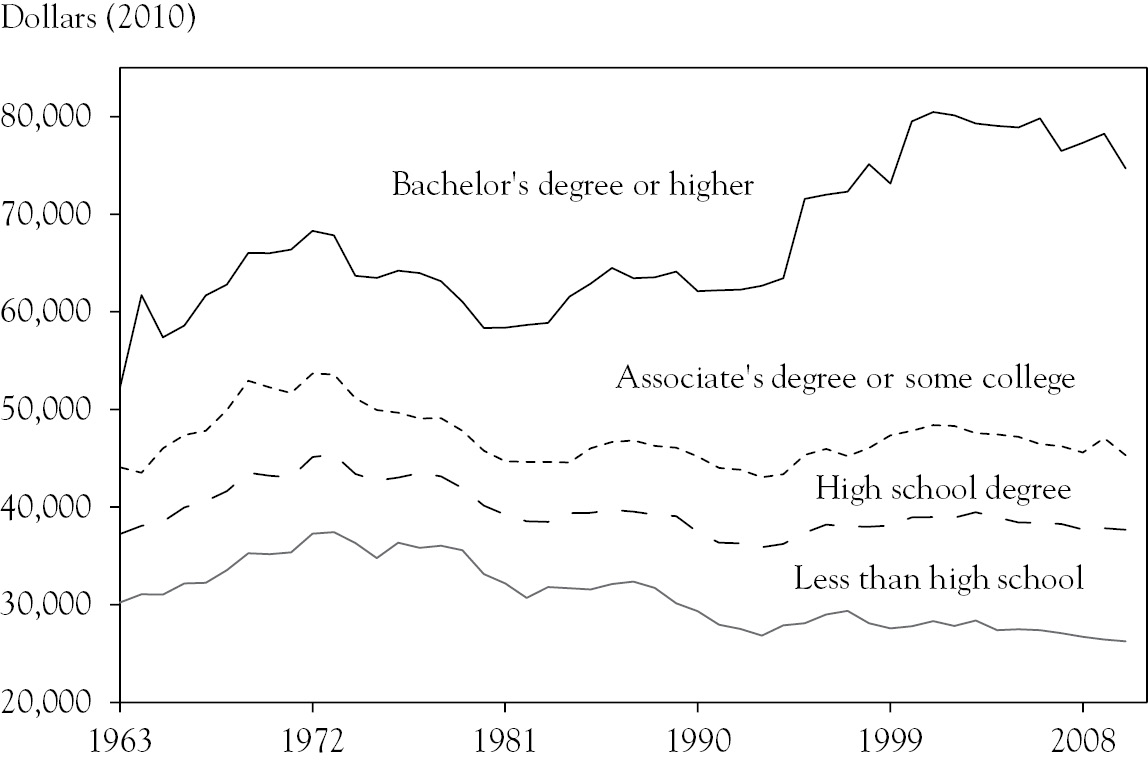

As shown in Figure 7.1, wages are also increasing much more rapidly for the most highly educated workers than for their lesser educated counterparts. In fact, after adjusting for inflation, the wages for those who did not complete college have barely risen over the last 40 years and have fallen significantly from their peak in the early 1970s. Those for people with less than a high school degree have actually fallen. In contrast, wages for college grads have risen handily.

Figure 7.1 Average annual earnings by worker education, 1963–2010

Note: The sample includes workers aged 25–65 who worked at least 35 hours a week and for at least 50 weeks in the calendar year. Before 1992, education groups are defined based on the highest grade of school or year of college completed. Beginning in 1992, groups are defined based on the highest degree or diploma earned. Earnings are deflated using the CPI-U. Calculations are based on survey data collected in March of each year and reflect average wage and salary income for the previous calendar year.

Source: Council of Economic Advisers calculations using March Current Population Survey.

But, as dramatic as this Council of Economic Advisors’ chart is, it masks one of the greatest disparities of all. By combining Bachelor’s degree holders with those with those with a Graduate degree, it somewhat overstates the differential between Bachelor’s and Associate’s degree holders and significantly understates the differential between Bachelor’s and Graduate degree holders. A similar chart by economists Daron Acemoglu and David Autor separates the results for these degrees. It shows that the salary gap between those who earn Bachelor’s and Graduate degrees has grown even wider than the gap that separates Associate’s and Bachelor’s degree holders.5 One recent study, in fact, found that the gap between those with Bachelor’s and Graduate degrees has grown from almost zero in 1963 to 27 percent in 2010.6

These disparities have continued throughout and in the aftermath of the recession. As shown in the 2013 Pew Research Trusts study referenced in Table 7.1 above, four-year college graduates (and to a somewhat lesser extent, those with associate degrees) not only had continually higher rates of employment than high school graduates, but that they were less likely to lose their jobs during the recession. They also had greater success in finding new jobs after being unemployed and suffered much lower declines in wages (5 percent) than did those with less education (10 percent for high school and, somewhat paradoxically, 12 percent for those with associate degrees).

The advantages of a college education, while already great, are growing.7 Median weekly earnings of college-educated, full-time workers are now 79 percent above those for similarly aged adults with high school diplomas. This premium has increased from 48 percent a mere 30 years ago. And this does not even include the fact that college grads are more likely to be employed in full-time jobs.

While inflation-adjusted wages for those who did not complete college have barely risen over the last 40 years and those with less than a high school degree have actually fallen, those for people with college-and especially graduate degrees have surged. College-educated workers now earn 79 percent more than those with just high school degrees.

Table 7-2 Employment rates by education Level—2007–2012

Source: Pew Charitable Trust

These wage advantages continue over one’s entire career. According to the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, by the time the average four-year college degree holder retires, he will have earned $960,000 more than his counterpart with a high school diploma.8 And, for STEM graduates from prestigious schools such as MIT and Caltech, these lifetime premiums can be even greater—about $2 million according to a 2013 PayScale analysis.9

Those with two-year associate degrees, meanwhile, earn an average of about $425,000 more, and those with some college (but not a degree) earn more than $240,000 more than those with just a high school diploma. The Brookings Institution Hamilton Project expresses the value of a four-year college education in terms of a return on your investment in college tuition and room and board.10 It estimates that graduates earn an average 16 percent annual return, even after accounting for lost earnings during college.

As great as these economic differences may appear, they do not even begin to account for the noneconomic advantages that college grads are likely to have over their less-educated counterparts. For example, they tend to have longer life expectancies, lower divorce rates, fewer single-parent families, and lower rates of smoking. Grads also tend to live in safer neighborhoods and their children attend better schools and achieve higher levels of academic and economic achievement. In fact, a number of studies show that U.S. intragenerational and intergenerational wealth mobility (the ability for individuals and their children to move from one economic class to another) has fallen dramatically, with the United States now having one of the lowest levels of mobility in the developed world.11 The best way to improve both your and your children’s economic fortunes, according to another Pew Charitable Trust study, is for you to earn a college or, better yet, an advanced degree.12

This education is becoming more important and more prevalent than ever. A record 33.5 percent of Americans aged 25 to 29 now have at least a bachelor’s degree (up from 24 percent less than 20 years ago) and another five percent have an associate’s degree.13 The problem is that almost half of these people do not have jobs that require a degree.14 But if you think these graduates have it tough, think about those a bit further down the educational ladder. They are losing or being displaced from traditionally non-college jobs by people with degrees.

Higher-Education: High-Skill Holy Grail?

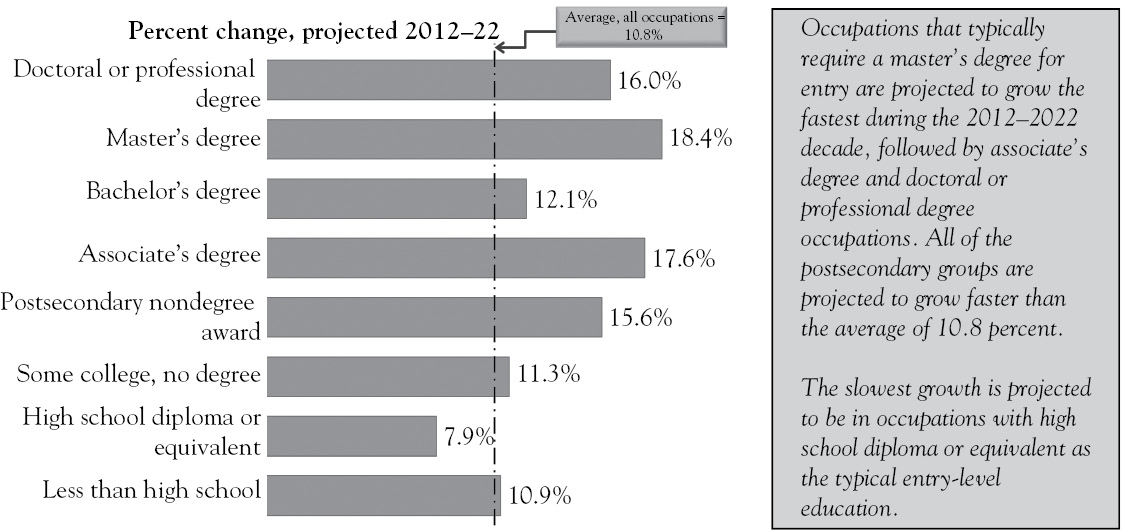

At first glance, given all the employment, income, and other disparities, it may appear that any student with a real choice in the matter should get at least a bachelor’s degree and, ideally, a master’s. Although only one-third of all jobs currently require more than a high school degree, jobs that require more than a high school degree are expected to grow significantly faster than those that do not.15 As shown in Figure 7.2, the fastest growing will be those that typically require advanced degrees (especially master’s) and those that require either an associate degree or some form of postsecondary certificate. Although jobs that require bachelor’s degrees are expected to grow at a faster rate than those that do not require any postsecondary degree or certification, they will experience the slowest growth of any of those jobs that do require post-secondary education. And which single job is likely to experience the fastest percentage growth over the next decade—organizational and industrial psychologists, whose ranks are expected to grow by 53 percent.16

Figure 7.2 Percent change in employment, by education category 2012–2022 (projected)

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2012), Chart on p. 2. http://www.bls.gov/emp/ep_edtrain_outlook.pdf (Chart on page 2)

Clearly, not all fast-growing, high-skill, high-pay jobs will require a master’s, or even a bachelor’s degree. Apprenticeships, as discussed in Chapter 9, can also be good onramps to good jobs. In fact, BLS estimates that jobs requiring apprenticeships will grow at an even faster rate than those that require master’s degrees—22.2 percent.17 There are, however, some important common threads among all types of good paying, high-growth occupations—virtually all will require some form of formal postsecondary education or training and many of the fastest growing, highest paying of them will require some form of STEM skills.

Questioning the Value of a College Education

Although the rewards of a college education can be great, they can also be speculative. You have to pay for these educations upfront, before you know what type of job you will end up getting upon graduation. Given the experiences of the last seven years, it’s of little surprise that many prospective students are questioning the value of a college education or the ramifications of the debt they will have to take out to pay for their educations.

Prospective students and their parents, however, aren’t the only ones questioning the value of a degree. A 2012 McKinsey Center for Government study found that only 42 percent of surveyed companies and 45 percent of recent graduates thought that colleges and universities had prepared graduates for today’s jobs.18 (In something of a startling disconnect, 72 percent of surveyed colleges thought their graduates were prepared!)

Although only 42 percent of surveyed companies and 45 percent of recent graduates thought that colleges and universities had prepared graduates for today’s jobs, 72 percent of surveyed colleges thought their graduates were prepared!

Some academics are also questioning what students actually learn from their college experiences. Richard Arum and Josipa Roksa’s 2011 book, Academically Adrift, questions whether colleges deliver what they promise, or whether they even teach the right skills.19 They demonstrate that many colleges are not delivering on their primary missions of teaching the types of critical thinking, complex reasoning, and effective writing skills (much less inspiring the type of self-discovery and reflection and instilling the type of lifetime love of learning) that have been the traditional hallmarks of higher education. In fact, their analysis of the results of College Learning Assessment test results suggests that 45 percent of graduates have no appreciable gain in critical thinking skills from a four-year degree!20 Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz, in their book The Race Between Education and Technology, agree that many graduates leave college without the high-level reasoning skills needed to succeed.21

Arum and Roska’s study spreads the blame among schools, professors, and students. For example:

• Many schools and professors offer too many courses with minimal requirements and lax grading; and

• Students take too many courses with minimal reading and writing requirements and have dramatically reduced the time dedicated to homework in favor of social activities.

But while the majority of students from a majority of schools show little gain in critical thinking skills over their college career, the study does find exceptions. Not too surprisingly, students whose parents went to college, those who had better grades in high school advanced placement courses, and those in more selective schools tend to show greater Collegiate Learning Assessment (CLA) gains over their college careers than do others.

Other academics, such as George Mason’s Bryan Caplan, contend that many colleges are becoming little more than diploma mills for certifying a graduate’s intelligence and competency (at least in the type of memorization and categorization skills and self-discipline that schools, from primary through college, typically teach, test, and reward). The sorting process, he contends, has become more important than the learning process.22 How and why has this happened? Students are increasingly looking for easy courses and social opportunities; parents for a road to their children’s career; and businesses for skills that can deliver immediate value. UCLA, which has conducted surveys and studies of incoming freshmen over the last 40 years, provides support for such assertions. As New York Times columnist David Brooks explains, these statistics suggest that high school graduates arrive at college with very different expectations and habits than did those in the mid-1960s.23

First, incoming freshman enter college expecting much better grades for much less work. In 1966, for example, 19 percent of incoming freshman graduated high school with A or A- averages. By 2013, 53 percent had these averages. That is despite the facts that recent graduates have done less homework (in 1987, nearly half of high school students did at least six hours of homework per week, compared with fewer than 33 percent in 2006) and were less diligent in attending class (In 1966, 48 percent of students said they sometimes showed up late to class, compared with more than 60 percent in 2006). But despite this, recent graduates rate themselves much more highly than past generations on leadership skills, writing abilities, social self-confidence and so on.

They also arrive in college with different expectations of what they hope to gain from college. In 1966, 86 percent of college freshmen believed that developing a “philosophy of life” was very important, compared with fewer than 50 percent today. Money, however, has become more important, with the percentage of freshman “going to college primarily to allow them to earn more money” increasing from 50 percent in 1976 to 69 percent by 2006.

While many colleges seek to fulfil traditional objectives (helping students discover themselves, learn critical high-level skills, develop philosophies of life, become good citizens, and so forth), they also have to cater to current student and parent expectations and accommodate the engrained habits of today’s students. Columbia professor Andrew DelBlanco, in his book, College: What it Is, Was and Should Be, questions whether any school can ever address such conflicting needs.24

These conflicts, combined with new challenges, such as the need to reduce ballooning costs and challenges based by Massive Open Online Courses (discussed in Chapter 9 has prompted a team of academics, working under Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen, to conduct a study on the future of colleges. The study, entitled “Disrupting College,” questions whether the current university model is even sustainable—except for the largest, richest, most prestigious schools.25

Some critics go further. The unschooling movement in general and the Thiel Foundation26 and the UnCollege27 organization, in particular, argue not only that college doesn’t deliver value, but that it can be downright detrimental. Colleges, they claim, don’t even attempt, much less succeed in teaching the real skills that are required for success. Thiel provides $100,000 grants to select students who skip college to focus on work, research, and self-education. UnCollege and a number of similar organizations provide encouragement, direction, and now, even formal programs to help young adults pursue self-education. (A number of such programs are discussed specifically in Chapter 9.)

Still, for all the drawbacks and questions, college continues to reign as the overwhelmingly preferred model for preparing for a career—not just for what you learn, but as a final opportunity to mature, for whom you meet, and not inconsequentially, for the credentials and the image that college confers.

Higher education, therefore, is becoming more and more popular, even as it becomes less and less credible, and probably, less and less viable. For example, as of October 2011, 68.3 percent of 2011 high school graduates were enrolled in colleges or universities—just below the record high.28 The actual number of attendees—21 million—has been climbing relatively steadily since the Great Depression. Meanwhile, as mentioned previously, the percentage of young adults graduating from four-year colleges has now reached an all-time high of 33.5 percent. And these figures do not include more than 500,000 students who were enrolled in nondegree-granting postsecondary institutions, such as technical training and certificate programs.

But even graduation is often not enough. A 2013 Accenture survey29 of 2011/2012 graduates, for example, found that while current college students generally believe that their degree will allow them to get and succeed in the job they want, those who had recently graduated and are in the job market have very different opinions:

• Fifty-two percent of grads with a two-year degree said they will need to get a four-year degree in order to get the job they want;

• Forty-two percent of four-year college grads expect they will need to pursue a graduate-level degree to further their career;

• Forty-eight percent of unemployed graduates said they would have fared better in the job market with a different major, and 57 percent expect to go back to school within the next five years.

Is College Worth It?

Unfortunately increased enrollment, or even national graduation rates, do not necessarily translate into improved college performance, much less increased employment. According to the Institute of Education Sciences, only 59 percent of full-time, first-time students who enroll in four year colleges actually graduate within six years and a depressing 31 percent in two-year programs graduate in three years.30

Those who leave without earning their degrees end up reaping the worst of both worlds. Although employment rates and earnings are somewhat higher than for those who do not attend college at all, they paid for the college experience, may have racked up debt, delayed their entry into the workforce (at least assuming they could have gotten a job), and probably suffered a blow to their egos.

And this does not even begin to consider the astronomical costs of getting a college degree and the sometimes crippling burden of student loan debt, both of which are discussed in gruesome detail in Chapter 8.

One thing is for sure. If you do decide to go to college, you must know exactly why you are going, what you intend to get out of college and then be sure that you get everything out of college that you intend. Getting a job should not be the only or even the primary objective of a college education. That being said, college requires too big of an investment to not consider how well it will prepare you for a career. After all, while the “average” college graduate more than recoups the out-of-pocket (tuition, etc.) and the opportunity costs (lost wages while they are in school) of going to college, everyone is not average. The PayScale survey that found the huge college premium earned by MIT and Caltech grads, for example, also found that humanities graduates from lowly ranked colleges may actually learn less than those who never attended college.9

Although college is too big of an investment to not consider how well it will prepare you for a career, getting a job should not be the primary objective. But whatever your objectives, you must know exactly why you are going, what you intend to get out of it and then be sure that you get everything you intend.

The “Major” Question

Deciding whether you go to college and where you go are critical questions. But, as suggested by the above example, the question of deciding in which field you major is becoming almost as important. This comes down to a couple of questions. For example, what do you really hope to gain from college (at least academically)? Do you want to prepare for a job; to “learn to learn” and to “love to learn,” to become an informed and well-rounded person; or some combination of these and others.

This can be a critical question. After all, the selection of your major is probably the single most important determinant of whether a college graduate will even get a job that makes use of their education.

• On one hand, as shown in the 2012 BLS College To Career report, graduates with degrees in healthcare, education, engineering, IT, and business tend to have the greatest success in finding jobs.31 Those with degrees in social sciences, and especially in humanities and the arts, generally have the least success.

• On the other hand, liberal arts and humanities programs are often seen as being more intellectually rigorous, providing the greatest breadth of learning experiences, and as being more effective in helping you develop the type of interdisciplinary, critical thinking, and communication skills that will be required throughout your career and your life. This being said, according to the Gallup-Purdue Index, while STEM and business graduates are much more likely than social sciences and humanities graduates to get full-time jobs (more than 60 percent compared with less than 40 percent), those of the latter who do get jobs are slightly more likely to find their work engaging.32

The question partially comes down to a question of what you really want from college. What are the relative values you put on pursuing your passion, getting a job, and developing long-term life and career skills?

As for the jobs question, the facts are hard to dispute. Those majoring in nursing, education, engineering, math, biology, computer science, accounting, and economics are not only far more likely to find jobs, they are also more likely to get jobs in their field. And except for education majors, they are also likely to earn higher salaries. Social sciences and humanities majors: much less so! (A more dated BLS report looks specifically at starting salaries for a range of liberal arts majors.)33

The selection of your major is probably the single most important determinant of whether a college graduate will even get a job that makes use of their education. Nursing, education, engineering, math, biology, computer science, accounting, and economics are likely to offer the best prospects.

This being said, liberal arts graduates from highly selective Ivy League and other tier-one schools typically have much greater success in finding jobs than do graduates from less selective schools. This is almost regardless of major. The vast majority of these graduates either go on to graduate school or land jobs before graduation.

Particularly attractive liberal arts graduates of less selective schools—those with the most in-demand majors, the best grades, the most relevant experience and accomplishments, the strongest references, and so forth—may also fare well in scoring good jobs. Morgan Stanley, for example, expects to hire 25 to 30 percent of its bachelor-level hires out of liberal arts, rather than business programs.34 But whichever major you choose, you will want to think long and hard about your choice. Some surveys suggest that about half of all recent graduates have come to regret their choices of majors.

The question of majors, what you gain from each, their respective employment and salary prospects—and ways of combining “practical,” “passion” and “learning” courses into a single educational program—are discussed in much greater detail in Chapter 8. But before jumping into a discussion of college, it’s important to mention some increasingly interesting alternative (or in some cases, additive) approaches to learning life and career skills and yes, even for preparing for and getting your first job.

The Non-College Options

There’s no question: Long-term success in virtually any career—much less the ability to shape a career around your dreams and maintain control of your career—will absolutely require education beyond high school. But although a four-year college is certainly the most widely accepted means of beginning this education, it is not the only means. It may not even be the best type of education for a particular individual or career.

After all, of the more than 20 million new jobs that BLS expects to be created this decade, fewer than 25 percent actually require a bachelor’s degree or higher.35 The majority—12.8 million out of 20.4 million total—will still require only a high school education or less (see Table 1.3 of the BLS’s Occupational Handbook).36

Although the vast majority of these jobs will offer low pay, few benefits, little job security, and few significant training or advancement opportunities, there are exceptions. But, as discussed previously, virtually all except the most unskilled of these will require some form of formal postsecondary education or training. This preparation may include:

• Traditional blended education or training programs for entry into a skilled trade, such as those offered by community colleges or apprenticeships programs;

• Shorter, less formal certificate programs, as for tractor–trailer drivers and cosmetologists;

• New, less-structured MOOC courses and, increasingly, more formalized multicourse programs that may culminate in certificates or degrees;

• Short-term “boot camps” that are intended to provide fast, intensive exposure to a particular discipline, such as basic programming or starting and managing your own entrepreneurial business; and

• Increasingly popular, increasingly structured non-college programs and gap years.

There are also opportunities to bypass even these educational programs in favor of less formal, self-directed programs. There are, for example, opportunities for especially motivated (and especially extroverted) young adults to go on their own missions of self-discovery, as by travelling, working in different jobs to understand what they entail, and then, as they get a better idea of what they want to do, get jobs (or more likely unpaid internships) in positions and with companies that may lead to a career.

Meanwhile, some companies are much more interested in your accomplishments than in your educational credentials or your chronological age. For example, a growing number of software companies (think Google, Facebook, etc.) are recruiting particularly talented college students well before graduation, showing them how they could learn much more (often $80,000–$100,000 starting salaries) by skipping the rest of college and going directly into a job. Many have already begun to target particularly promising interns who are still in high school.

Nor do you necessarily need sterling technology to score a good job without college. Good salespeople, for example, are always in demand. A bright, ambitious person, with the right training, communication, and empathic skills and a detailed understanding of a product’s capabilities and how they can be used to address a pressing customer need, will almost always have a choice of job opportunities. And then there are entrepreneurs. They can come from anywhere—no specific education or training required.

Or you could bypass all of this by starting your own company straight out of high school, or partway through college. After all, it worked for Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg. Moreover, one ex-technology magnate even offers no-strings $100,000 grants to particularly promising students who drop out of college to launch their own companies.

These and many other non-college options are discussed in much greater depth in Chapter 9.

Where Do You Go From Here?

So what type of education and experience is right for you? That requires you to answer a number of questions. For example, how did you do in high school? What form of learning is most effective for you? How self-directed are you? What are your career objectives and how thoroughly have you explored and prepared for them? Can you afford college? What are your family responsibilities? Even if you focus primarily on employability and salary, the answer varies greatly by factors including:

• Which career do you plan to pursue and what combination of education, training, skills, and preparation does it require?

• What combination, above the base requirements, will give you a particular advantage in this field?

• What experience and accomplishments do you currently have in your targeted field?

• Which school are we talking about: Harvard or the proverbial Podunk State? What is the educational and employment value of a degree from that school?

• Which major do you plan to pursue?

• Exactly what do you expect to get out of your education and how can you ensure that you get that value?

• Do you have the direction, motivation, and self-discipline required to develop and pursue a nonstructured education program, or do you need a more gradual transition (i.e., college or apprenticeship) from the structure of high school to the “real world”?

• What will be the cost of the degree? Is it a private or public school, what types of financial aid are available, and can you ameliorate expenses such as by living at home or working part time?

Many people are capable of doing quite well without a formal postsecondary education or apprenticeship. This is even true for a handful of people who plan to enter highly demanding, high-skill occupations. This being said, a four-year college education provides much more than preparation for a career. It (along with community colleges and apprenticeship programs) also provides additional opportunities to mature, and more gradual transitions from high school to the world of work, careers, and financial responsibility.

But whatever form of education you prefer, you will need a combination of academic education to develop the technical skills and to understand the processes and the context of your field, and experience to develop the practical understanding of how to perform the work efficiently and effectively. Even more importantly, as stated by Harvard’s Graduate School of Education and Innovation Lab’s Tony Wagner, “the world no longer cares how much you know; the world cares about what you can do with what you know.”37 And if and when you do graduate, you need more than an education and potential, you also need skills—skills that will allow you to deliver immediate value to an employer.

The world no longer cares how much you know; the world cares about what you can do with what you know. Getting and succeeding in a good job increasingly requires skills that will allow you to deliver immediate value to an employer—and especially the personality traits discussed in Chapter 3.

In the end, however, you also need something else. You also need the type of personality traits that, as discussed in Chapter 3, that will be increasingly required for success in any field. As Wagner explains, “To succeed in the twenty-first century economy, students must learn to analyze and solve problems, collaborate, persevere, take calculated risks, and learn from failure.”33

So, with these caveats, let’s now take a deeper look into the most common means of preparing for a professional, high-skill career: four-year colleges.