Your First Job as Launchpad for a Lifelong Career

Steps 15 Through 20

70 percent of American workers are “not engaged” or “actively disengaged” and are emotionally disconnected from their workplaces

—Gallup “2013 State of the American Workplace Report”

Key Points

• Think of your first job as a launch pad for your career.

• The best jobs will be those you make, not those you take.

• Learning opportunities and doing what you love should be your primary criteria for your first job—not salary.

• While internal advancement opportunities are certainly important, long-term marketability of your first job experiences is critical.

• Are you best suited to a large and mature, small and high-growth, or your own company?

• If you don’t like your job or career path, change it—Fast.

This chapter is not a job search guide. You can find many good books, websites, workshops, college career service offices, and personal coaches who do this quite well. So, rather than examining what you have to do to sell yourself to the employer, this chapter focuses on what you should look for in your first real career-track job and in an employer.

This may sound like putting the cart before the proverbial horse. But, if you have followed the steps outlined in previous chapters, you will be well prepared for a formal search long before you are ready to actually begin to look for your first full-time, career-track job. You will have:

• Identified a number of potential career paths that build upon your skills, draw upon your interests, and ideally, allow you to pursue your passions;

• Evaluated the employment opportunities in these fields and understood the skills and traits employers are looking for in candidates to fill the positions you are targeting;

• Crafted and honed your own differentiated brand and triangulated it to match both your own interests and skills, and employer needs;

• Engaged in experiences and developed the skills required not only to prepare you for your first job but also for any career in which you may eventually find yourself;

• Begun to develop a network of advisors who can help you tune your resume, advise you on interview techniques, refer you to potential employers (since so many of the best jobs come from referrals), select the most promising opportunities, and serve as sounding boards throughout your career;

• Gained extensive experience in setting up and conducting the type of information interviews that are so critical in finding unposted jobs that are usually so much more interesting than publicly posted jobs, and in presenting yourself to people who may be in a position to create a job around your unique capabilities; and

• Gained hands-on experience in your field through part-time jobs, internships, or class projects (some of which have the potential of morphing into formal job offers).

Moreover, if you have followed this process and are now looking for the job of your dreams, you should already have a pretty good idea of which organizations are most likely to offer the types of jobs you have targeted. You may have already spoken or even interned with some of these firms.

This chapter identifies many of the critical issues you should consider in determining what to look for in your first job and employer. It discusses these issues in order of the priority that I—with the benefit of hindsight—would place on each in targeting a search and in selecting among offers. Then, for when you begin your job, it suggests how you can get the most out of your position and provide the most value to both your employer and yourself.

Although the following sections are generally aligned with the six steps (number 15 through 20) associated with getting and capitalizing on your first job, there are a number of discrepancies. The reasons: First, the sections are organized in order of importance, rather than when you should first consider them. Second, many of the factors are interrelated and, as with most of the 20 steps, must be evaluated in conjunction with each other.

Matching Your Needs with Your Employers (Steps 15 Through 17)

When you’re finally ready to strike out on a search, exactly what should you look for in your first job, or in your first couple of jobs? Easy: you want your dream job in a world-renowned company, with a salary beyond your dreams, a generous bonus, your own assistant, a flexible work environment, “Google-like” perks, and a career path that will take you to a vice presidency in two years.

But what should you settle for when you discover that job isn’t available? Would you be willing to accept any job, at any salary, as a means of getting your foot in the door, with the expectation that as you prove yourself you will shoot up through the ranks?

On one hand, you should definitely prepare for and work long and hard to get the job of your dreams. If you succeed, congratulations! Take the job, work hard, and create your dream life. But if you can’t get this job, I strongly recommend against the opposite course of trying to get any job you can (at least unless you are out of all options). After all, employers don’t want an employee—especially a high-skill, high-salary employee—that is desperate for a job and doesn’t care where they work or what they do. They want someone who understands and is incredibly motivated to do the specific job that the employer is looking to fill.

Nor, at the other extreme, do they want somebody that is so locked into some idealized job or career path as to be inflexible. Employers, after all, aren’t in the business of creating a dream job for entry-level employees. They’re in the business of finding the specific individuals who are best suited to filling the job they have available (and that have the potential of delivering much greater value in the future). Not until AFTER you have proven yourself in your first job and have demonstrated the value you can deliver, should you even try to tailor this job, or request another job that is tailored to your needs. And even then, you have to position yourself as the ideal solution to an employer need—either a need that they already recognize or better yet, a need that you identify for them and have already demonstrated that you can address.

But I digress. When looking for your first job, you have to present yourself as someone who:

• Knows yourself, what you are good at, and what you are looking for in an initial job;

• Has a realistic understanding of your skills, how you can use them to deliver value to the specific employer and job, and also your limitations;

• Has demonstrated an ability to focus on and relentlessly pursue an objective (including the process of targeting and pursuing a job); but is also

• Sufficiently pragmatic and adaptable to recognize and fully capitalize on opportunities beyond your predefined visions.

Employers are looking for people who recognize that their first job isn’t a reward for or capstone to their education, but an opportunity to begin an exciting new phase of their lives; an opportunity to learn new skills and to apply them in new ways; and a chance to use the first job as a foundation on which they can build a long-term career that will deliver real value to the company.

But exactly what should this job look like? What type of responsibilities and growth path should you look for? What salary and benefits? Just as importantly, where should you look for this job: in a large corporation, a small company, a start-up, or your own business? And speaking of where to look, do you want to live in or near your home town, or as I did, get as far away from your home town as possible? If the latter, what are you looking for in your new home? What size city? What leisure and cultural opportunities? What country?

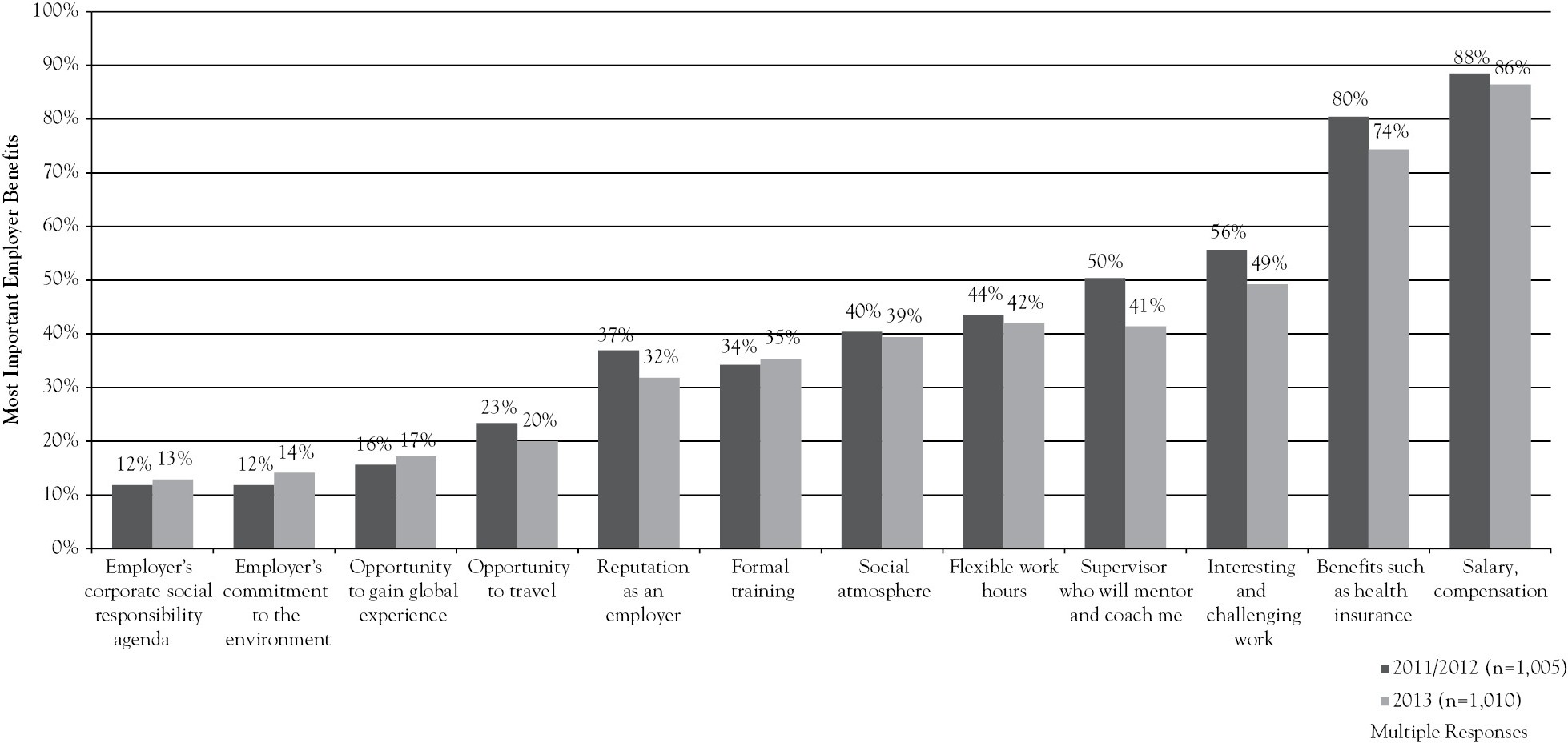

A 2013 Accenture survey shows that 2012 and 2013 graduates already have pretty good ideas of what they are looking for from an initial employer. As shown in Figure 10.1, compensation and benefits are, by far, their primary goals.

Figure 10.1 The most important benefits for an employer to offer

Source: “Accenture 2013 College Graduate Employment Survey: Key Findings” (2013), Slide 37.

This is certainly understandable given years of living on a student budget. Salary can also be a powerful validation of the value you believe you can bring to the world. But should these really be the most important criteria in evaluating a job that has the potential of being the foundation of a 40-year career?

Let me suggest a number of factors that you may want to consider above salary and benefits.

First Job as the Launchpad for Your Career—Whatever That Career May Be (Steps 15 and 16)

Given the changes in employers approaches to, and Millennials views of employment, you are likely to have many jobs over your working life. These jobs may include anything from part-time and summer jobs when you are in school to unpaid internships or fellowships, to jobs with a large corporation, to work in a business that you built around your own idea. Each of these jobs should help you learn something new about yourself (such as what you enjoy, what you’re good at, and what additional skills you need to develop), the world of work (discipline, teamwork, adaptability, and so forth), and what you want and do not want in future jobs. Each of these positions, regardless of how unlikely it may initially seem, also has the potential of leading to a rewarding, full-time career.

Whatever combination of precollege or college jobs you may have had, you should look for more in your first real career-track job. This job, after all, will likely provide a critical foundation for your ultimate career; regardless of the field or company in which that career may be or the skills it will require.

Given this importance, just what should you look for in this job? Before you try to answer, consider an important factor. You should look for different things from a job during different stages of your career and depending on your unique life circumstances. For most young adults, your first job is likely to be your first real exposure to the real world of work—the first job in which you will hopefully support yourself, live on your own, and be responsible for managing your own lives.

Although your choices may be limited by student loans, family commitments, and other obligations, you should treat your first job as one of the greatest and most important learning opportunities of your life (certainly more so than any of your time in school). Although you certainly need to consider issues such as salary, job titles, and job security, you’ll have plenty of time to improve upon these in later stages of your career.

Among the most important factors to assess in deciding on your first job are:

• What will I learn and how will I be challenged?

• What skills will I learn to apply and what new skills will I develop?

• Will I enjoy and get fully engaged in my work?

• What advancement opportunities will it provide?

• Will it improve my marketability?

• Which industry and company size will offer the best learning, growth, and long-term career opportunities?

• Will it allow me to expand, enhance, and especially deepen my network by developing deep professional relationships?

• Is the company’s culture and image consistent with my needs and values?

• Are the salary and benefits appropriate and competitive?

• Where do I want to live?

• Although many of these factors are interrelated, let’s look briefly at each.

Will I Enjoy My Work? (Step 16)

It’s probably safe to assume that regardless of your job, you won’t enjoy every task. No matter how much you may enjoy the core responsibilities of your job, every job has multiple components. You may be required to sit in endless meetings, submit meaningless administrative information, prepare and give presentations, or travel to locations in which you have no interest.

Still, in the end, you want to be able to go home with a sense of accomplishment from doing something you enjoy, and doing it well. Not only is this good for your psyche, it is also good for your long-term career growth. Enjoying what you do will incent you to work harder and learn more. On the other hand, continually engaging in meaningless or distasteful activities is likely to prompt you to disengage and become either complacent or rebellious. In addition to making you miserable, lazy, or both, it could get you fired or, at the very least, jeopardize your future job prospects. It will certainly make it less likely that you will be offered interesting assignments or promotions or get strong referrals or recommendations from colleagues or superiors.

Can you judge whether you are going to like a job before you accept? You should already know, from your own personal inventories and from evaluating your previous experiences, what you are and are not good at, and what you do and do not enjoy. Ask what the job will entail and what a typical day will look like. Then try to verify it. And what happens if, even after exercising due diligence, you find yourself in a job that is not challenging or that you do not enjoy? Speak with your supervisor or personnel department. Is there a possibility of modifying your job to better address your strengths? Can you volunteer to perform other tasks that need to be done and, after proving your value, gradually shed parts of your old job in favor of new ones? Can you qualify for other jobs in other groups within the company? If so, great: If not, you may need a plan to find another potential job.

After all, no matter how many opportunities you may find within your initial employer, the odds are that you will eventually change employers, not to speak of careers. Although reliable numbers are hard to find, a 2007 study by Princeton’s Henry Farber found that men have an average of 11.4 jobs in their career (including different jobs in the same company) and an average tenure of 4.4 years: Women have an average10.7 jobs.1

This being said, younger workers, especially those in their 20s, change jobs most frequently, with turnover steadily reducing as they reach their 30s and beyond. These figures are broadly confirmed by the most recent iteration of a 30+-year longitudinal study by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. It found that younger Baby Boomers held an average of 11.3 jobs between ages 18 and 46. Nearly half of these jobs were held between ages 18 and 24, with 69 percent of these lasting less than a year and 93 percent lasting less than five years.2

Interesting, but what does it mean for you? Millennials are very different than even younger boomers. They have very different ideas of what they are looking for in jobs and the role that work should play in their lives. So, BLS launched a similar study that focused on Millennials, at least older Millennials born in the early 1980s. While results are necessarily cover shorter periods than the previous study, it is found that 57 percent of jobs held by workers between the ages of 21 and 26 lasted one year or less and another 14 percent lasted less than two years.3 Although it is certainly too soon to draw long-term conclusions, it appears that Millenials are indeed on track for more, shorter duration jobs through their careers.

The good news is that, from hindsight, people do not typically regret the frequency of job changes—at least when they are voluntary. In fact, a failure to change jobs, change careers, or to leave a current job to start a new company is often cited as among the most common of all career regrets.4 This can be especially true for those who feel locked into careers they no longer enjoy due to debt, family obligations, their investment in training, inertia, perceived risk, the fear of failure, and so forth.

People do not typically regret the frequency of job changes—at least when they are voluntary. In fact, a failure to change jobs, change careers, or to leave a current job to start a new company is often cited as among the most common of all career regrets

No career is immune from these feelings. Multiple surveys, for example, have found that 40 to 50 percent of lawyers are generally dissatisfied with their careers. Even doctors have concerns.5 Only about half of those represented in one 2012 survey would choose medicine as a career if they had to do it again: only 40 percent would choose the same specialty.6 And remember, if you are dissatisfied with your career, it’s much easier to change when you are young, than when you have a family, a mortgage, and college and retirement funding obligations.

What Will I Learn in My First Job? (Step 16)

Your first career-track job should, as discussed previously, be one of the biggest and most important learning experiences of your life. You will not only learn how to develop the skills needed in your chosen field but also get a chance to explore many others—possibly discovering areas that may interest you even more than your original field.

Ideally, this job will build upon your education, allowing you to apply and master skills you learned in college. Even more importantly, it will take you out of your comfort zone, forcing you to work in teams with all types of different people, with different skills across many functional areas, and from different backgrounds. This should help you develop not only a broad range of functional skills but also people skills and, even more importantly, perspective as to how different jobs and skill sets fit together.

The job should force—and help—you to develop a broad range of skills, beyond those you have previously developed: skills that will be valuable and transferable across whatever position you may hold in subsequent jobs, careers, and industries. It should provide responsibilities and challenges that will help you grow as a professional, as well as give you a sense of accomplishment. Ideally, it will give you a chance to actually work in different types of jobs, under and with people who are committed to helping you learn. And, it will ideally provide a lot of formal training.

Your first career-track job should be one of the biggest and most important learning experiences of your life. It should allow you to apply and master skills you learned in college, take you out of your comfort zones, force you to work in diverse teams provide invaluable practical exposure to hwo companies operate.

Unfortunately, such jobs are few and far between. According to the previously referenced Accenture survey, although 77 percent of 2013 graduates expect their first job to provide formal training, only 48 percent of 2011/2012 graduates say they actually received this training in their first post-college job.7 According to Wharton professor Peter Capelli, few companies are still willing to invest in training new employees.8 They are looking for people who can fit right into an empty slot and deliver immediate value. Back in 1979, for example, companies gave new employees an average of 2½ weeks of training per year. By 1991, only 17 percent of employees reported getting any training during their first year. In 2010, only 21 percent of employees claimed to have received any training during the previous five years. The good news, found in a 2013 Accenture employer survey, shows that many companies acknowledge that they have not spent enough on training and that 51 percent plan to increase their budgets.9

A number of the leading—and most sought after—employers still provide training and opportunities to work across functions and departments. Their numbers, however, are limited. While start-ups and small companies seldom provide formal training, they, unlike many larger organizations, may not only allow but also actively encourage you to exercise many different types of skills in your job or to participate in a broad range of projects in other departments.

When interviewing for your first job, you should ask specifically about training programs and what they consist of and opportunities to work with other groups within the company. Then try to verify what the company is telling you. Search the web, ask your career services office, monitor social networks and job boards, and ask your continually expanding network of advisors and mentors. If the job and the company you want provides formal training, take full advantage of it. Generally, however, you should be prepared to train yourself and to create your own ongoing learning agenda.

What Advancement Opportunities Will It Provide? (Step 16)

Your first job (or at least one of your early jobs) must be a steppingstone, rather than a dead end. While you must understand the initial responsibilities of your first job and the primary factors on which your performance will be judged, you should be just as concerned with where the job will take you. This is much more than promotions and salary increases.

How, for example, can your current position evolve as you demonstrate an ability to accept greater responsibility? What are the likely career paths, both within your initial department and throughout the company? How will these career paths be determined? How personalized will they be? Will you have regular performance (as distinct from salary) reviews? How much flexibility will you have in moving into other functions within the organization (to broaden your perspective) and how will your position prepare you for these? Does the organization encourage lateral, as well as vertical moves?

Although any good recruiter can tell a good story about a company’s advancement opportunities, ask for examples. What, for example, was the path taken by your initial manager? By her manager? Can they provide examples of how career paths have evolved as the individual’s interests evolved and as they showed potential in other fields? More importantly, does the company provide mentorships to help newbies assess their options and plan their moves? Then, go to LinkedIn to trace the career paths of people in the company. You must, however, be judicious in your queries. After all, while every employer should be interested in your potential, they also expect you to focus on and excel in your current job. You don’t want to appear so preoccupied with where you will go next as to appear disinterested or disengaged from today’s work.

This gets back to the company’s reputation. Do they have a reputation for training their employees, for proactive career planning, for exposing people to different types of jobs? Do other companies seek out the company’s employees to fill their own managerial and executive slots?

You should also think well beyond your next position to your long-term career goals. You certainly don’t want to lock yourself into a predetermined career path. Planned moves may be stymied or more interesting opportunities may arise. It is, however, never too early to begin planning for the type of skills that will be beneficial for your future. And while returning to school may be the last thing on your mind upon graduating from college and beginning your first job, it shouldn’t be. According to the previously mentioned March 2013 Accenture survey, 57 percent of recent graduates believe they will need more training to get their desired jobs.10 Forty-two percent of these expect this to require a graduate degree and 23 percent plan to take graduate-level or online courses that will not necessarily lead to degrees.11

What type of education? If you’re in a rapidly changing field, such as technology, you must continually update your skills, or risk being relegated to legacy technologies. If you want to climb the management ladder, an MBA from a top-tier school will certainly help. If you plan to start your own business, Chapter 9 suggests all types of programs geared to aspiring entrepreneurs.

Given this need for continuing education, not to speak of the cost of obtaining it, you should at least ask about a company’s tuition reimbursement policy and its flexibility in allowing you to balance work and school schedules. Even if you don’t currently expect to use it, it will at least suggest that you are interested in continually learning and expanding your skills.

Will the Company and the Job Improve My Marketability? (Steps 16 and 20)

There used to be an implicit bond between employer and employee. The employee demonstrated competence and loyalty, and the employer reciprocated with job security, seniority-based raises, and moves up the career ladder. For better or worse, those days are gone. Employees must assume responsibility for managing their own career paths.

In an ideal world, you will respect the company in which you get your first job, the culture will be compatible with your own values, and it will offer opportunities for you to advance your career in a way that benefits both you and the company. If not, you should be in a position in which your first company (in addition to your first job in that company) provides a solid steppingstone into another job or organization. Consulting firms and law firms, for example, are built on this model. Few initial hires ever become partners. Other companies, however, covet the training, skills, the perspectives, and the connections that hiring lawyers or consultants from leading firms can bring to their own companies. And it often behooves the initial employer to encourage and even facilitate such a move since alumni often recommend or hire their previous employer to provide specialized help.

The primary factors underlying your marketability are intrinsic to yourself: the skills you possess, the results you have produced, the breadth and especially the depth of the network you have built, the strength of their references and recommendations, and so forth. You must, therefore, continually strive to enhance your own marketability. Of course, you should continually develop your core functional skills—specifically those required in your specific role—as well as those of the next position to which you aspire. Marketability, however, entails much more than developing specialized skills. As discussed, it also requires development of a range of complementary “transferrable skills,” broad perspectives, good judgment, and deep and subtle “people skills”—not to speak of an ability to effectively market yourself and sell your capabilities and the type of value you can bring to an employer.

Another key marketability requirement is using your current job and the relationships you form to expand your network and to cultivate the type of relationships that can blossom into sponsorships, mentorships, recommendations, referrals, and even job offers. Although you certainly need for people to respect you, do they like working with you? Do they trust you? Do they want you to work with or for them? Are they willing to put their reputations on the line to recommend you to a friend or colleague?

You are, after all, at least partially known by the company you keep. You want to make sure that your first employer is respected (both in its own right in addition to the ways it trains and prepares its employees) by other potential employers, both within and beyond its industry. For example, two years in a company recognized to cultivate talent (such as Proctor & Gamble, Coca-Cola, Kraft, and IBM) could prove to be more valuable than five or more years in a company that is not known to develop their talent.

Although advancement opportunities within your first company are important, it is even more important for that employment to improve your overall marketability. Two years in a company recognized to cultivate talent could prove to be more valuable than five in a company that is not known to do so.

Other types of reputation also matter. How well respected is your superior and your department, both within the organization and beyond? Is your department known as a source of talent, both within and beyond the company? Is your manager, and her superiors, respected throughout the organization and the industry? More importantly, have you earned the respect of your manager, your peers, and others throughout your company as well as in professional organizations to which you belong? Do they respect you and your skills? Do they see you as a team player? Perhaps most important of all, do they trust you and your integrity?

Although the reputation you develop in your job and that of the company for which you work will be critical in improving your marketability, your public identity and reputation outside your company is also important. This reputation, which can be based on your interests, your civic involvement, and your social activities, can help demonstrate your breadth as an individual—that you are much more than your job. It should reinforce your business identity around your competence, your judgment, your social and leadership skills, and your willingness and ability to pitch in and help, both individually and especially as part of a team. This reputation, and the connections you build around it, can also put you in contact with people and organizations that can help in your career or introduce you to totally new career opportunities, way beyond anything you may have imagined.

Which Industry and Company Size Will Offer the Best Learning and Growth Opportunities? (Step 15)

A tough question to which there is no easy answer. If you have a deep interest in a particular industry, that’s probably a great place to begin your search. You should, however, look at your options pragmatically. Generally speaking, as shown in Step 8 (see Chapter 4, maturing industries with established industry structures and slower growth rates are more likely to be dominated by large companies, offer highly structured jobs and stable work environments, and predictable, albeit gradual promotions and salary bumps, along relatively well defined career paths.

Young industries with fast growth rates typically offer less structure, fewer training and mentorship programs and more risk than more established industries. These fast-moving, less structured environments, however, are often more open than mature industries to hiring people with nontraditional backgrounds and offer greater flexibility in job descriptions and career paths. Although they often offer less job security, they can provide more opportunities to experience different types of work and offer more long-term career opportunities and growth prospects.

They are almost inherently faster moving, higher risk, higher reward environments. Not all companies (or even entire industries) will succeed. But, even if a company fails, it should expand your growth prospects, at least if it provided a great learning experience and is well-regarded in its space. Many high-growth companies, after all, value the perspective of people who have “been through it all before.” This is especially true if you use your time in your first company to build a strong reputation and network, develop high-demand skills and if the industry (even if not your specific company) continues to grow.

This is certainly more than can be said for industries that are at the other end of their lifecycles. Declining industries can combine the worse of both worlds—slow career and salary growth and a lack of job security. But even here, if you develop a good reputation, a strong network, and strong skills that are readily transferable to other industries, you should be able to find another job.

The questions about company size are often analogous to and inter-related with those of industry. Mature industries, for example, tend to be dominated by large and mid-size companies: New industries can be “cluttered” with a lot of start-ups. Generally speaking, the larger the company, the more structured the organization, the job and the career path, and the more formal the orientation and training programs. The smaller the company, the less structure, the less support (meaning that you have to do more for yourself) and the more likely you are also to get to wear many different hats.

Generally speaking, the larger the company, the more structured the organization, the job and the career path, and the more formal the orientation and training programs. The smaller the company, the less structure, the less support (meaning that you have to do more for yourself) and the more likely you are also to get to wear many different hats. This having been said, a company’s growth rate is even more important than its size.

A company’s growth rate is even more important than its size. Apple is a very big company. And, while it does have much of the structure of big companies, its high growth rates and even higher margins allow it to attract some of the best talent in the industry, offer some of the best salaries, and provide virtually unlimited career growth opportunities. The same is generally true of Google. Smaller, well-capitalized technology companies, particularly in social networking and gaming, can offer generally similar opportunities, albeit typically with less structure, more opportunities for working in fields beyond your job title and with less job security. They are also more likely to offer lower salaries in return for greater upside potential, should the company succeed.

But with any start-up or young company, there is also the risk that the company may fail. Although any size and age company can fail, one recent study found that 50 percent of start-ups (including 63 percent of those in the information industry) fail within four years and 71 percent fail within 10.12 Bloomberg considers even these figures to be wildly optimistic.13 It estimates that 8 of 10 companies fail within their first four years. This is absolutely not to discourage you to take a flyer with a start-up, but if you do, think about how and where and how you may wish to land.

Which is better for you? It largely comes down to the type of environment and the type of structure that is best suited to the way you learn. After all, as discussed previously, your first job is all about learning!

Will It Allow Me to Expand, Enhance, and Especially Deepen My Network? (Steps 18 and 19)

Networking through relatives, friends, colleagues, former managers, and especially the guides and mentors you met through your career preparation interviews can be one of the best ways of finding a job. First, more than half of all jobs are thought to come from informal channels. More important than the number are the type of jobs that come from networks: these are often unadvertised jobs that can be tailored to the unique capabilities of an individual.

Once you get a job, networking takes on a very different flavor. Professional networking is not about collecting names and “likes” on Facebook. It is about forming deep, trusting, mutually beneficial relationships with colleagues, managers, and other professionals from whom you can learn, bounce ideas off, seek advice from, and when appropriate, get referrals and references. As discussed in previous chapters, every stage of your education and your career, not to speak of your social and extracurricular life, provides opportunities to meet and seek the counsel of others. This is particularly true inside your company.

Although your company network should include people from all parts and roles in the organization, two forms or relationships are particularly critical, especially for people at the early stages in their careers: those with mentors and sponsors. Some companies have formal mentoring programs, where established professionals volunteer or are assigned to mentor new hires. Sponsors are even more important than mentors. They provide not only advice, feedback, and referrals, but they also put their reputations on the line by using their influence with their peers and superiors to proactively advocate for you. They may promote your accomplishments, invite you to meetings that are typically above your station in the organization, and even take you with them as they move up the organization or to a new company. In return, you must live up to their expectations; delivering stellar performance and loyalty and making them look good.

Just where do you find such mentors and sponsors? Although they can come from anywhere, the most logical initial work mentor is your manager. In fact, your relationship with your manager should be one of the most critical determinants in deciding if a particular job is right for you. You want a manager who will treat you as an apprentice (and ideally a confidant) rather than as a worker. Someone who will take the time to explain what they are looking for, provide you with the tools and the guidance you will need to deliver, and then provide constructive feedback on your performance. You want someone who will care about your success in your job and the organization, will honestly advise you, and will help you find the right place and advance in the organization.

Professional networking is not about collecting names and “likes” on Facebook. It is about forming deep, trusting, mutually beneficial relationships. In the end, the depth of your relationships will be more important than the breadth.

Although it’s impossible to tell for sure in advance whether your prospective manager will provide such help, you can look for hints. What type of chemistry do you feel when you speak with her? What is the atmosphere in her department? What type of enthusiasm and camaraderie do you see? Look also beyond the walls of the company. What, if anything, can you learn about your prospective manager from your personal network? From LinkedIn and other social media sites? What is her record in retaining people, in getting them promoted? What do people who used to work for her say?

Your prospective peers—the people you are likely to work with, rather than report to—may well be among the best sources of information. Ideally, the company with whom you are interviewing will have you speak with such a person (ideally in a more casual setting, such as over lunch). If they don’t, ask if you can speak with one of these people.

Professional networking should go beyond the company in which you work and include those in other companies who work in the same or complementary fields—people that you meet such as by:

• Attending professional events and volunteering to serve on professional organization committees and boards;

• Presenting to or working with your company’s partners, clients, and customers; and of course by

• Continually expanding the size of your LinkedIn and other social networks.

Your network should also extend into complementary professions. This can include people with similar and complementary interests such as from clubs, sports teams, civic activities, or religious organizations. After all, people with totally different professions and backgrounds can provide you with different perspectives, different sources of advice, and can, as mentioned previously, introduce you to totally new career opportunities.

And don’t forget online communities such as LinkedIn, Monster.com, and Jobvite. Not only are they important networking tools, they are also valuable recruitment and job search tools. LinkedIn, as discussed in a recent Bloomberg Businessweek article, is used as a recruiting tool of 97 percent of surveyed companies! Facebook, meanwhile, has introduced its own professional networking application, BeKnown, which is being integrated with Monster.com.14

Just as “true” networking entails much more than collecting virtual friends, the deeper the networking relationship, the deeper the commitment you make to each other. Keep people in your networks apprised of your progress, send them information that you believe may help them, and introduce them to people with whom they may share interests. And, of course, continually treat them with respect and integrity: showing them at least as much loyalty as they show you. True networking is, in other words, a two-way street.

Speaking of two-way streets, the further you advance in your education and your career, the greater your opportunity—and your obligation—to help others who are coming up behind you. In other words, be both a mentee and a mentor throughout your entire career. Being a mentee will, in fact, help you to become a better mentor.

Is the Company’s Culture and Image Consistent with My Needs and Values? (Step 16)

No matter where you end up, you’re probably going to spend at least 50 hours a week at work—even 80 hours in some jobs. For better or worse, a good part of your identity, at least to people you just meet (and increasingly to your own self-image) will be shaped by their image of the company at which you work. You should feel comfortable with the environment and the people with whom you work and with what the company stands for.

What type of feel do you get when you walk into the office? Is it very formal, structured, and fast-paced; or is it casual, relaxed, and collegial? Are the people you meet frazzled, curt, and strictly down-to-business; or are they more easy-going, conversational, and helpful? What type of vibe do you pick up from interactions among people who work there? Do the company and department appear to have a top-down, command-and-control structure or more of a collegial, peer-based culture? Does it appear that employees respect and proactively help each other, or is everybody competing with each other?

Does the company offer a flexible or structured work environment? Do people work in offices, cubicles, or open spaces? Do all offices and cubicles look the same, or does each reflect the occupant’s individual taste? Are people all heads-down at work, or are people gathering around speaking and playing games? Does it have strict hours or does it allow employees to tailor their hours to their needs? Do they encourage or discourage remote work?

These questions don’t have any right or wrong answers. It is all a question of the environment in which you are most comfortable and can best learn, in which you will do your best work, and what you are looking for at a particular stage in your life and your career. You may, for example, thrive in fast-pace, top-down, pressure-cooker environment, like Wall Street. Or you may prefer an equally hardworking, but much less formal, less hierarchical, and more laid-back, collegial environment, like Silicon Valley. Or perhaps, you are looking for more of a work–life balance of only working 40 hour weeks. You may be relatively laid back, but voluntarily choose to begin your career in a high-pressure environment as a means of maximizing your initial learning (and earnings) and creating a foundation for future, lower stress jobs.

But whatever you choose, you want to know what you’re getting into before you accept a job. Your initial experiences with the company’s recruiters and interviewers and in observing the office can give you an idea of what the organization is like. To really understand it, however, you need more direct, less structured view of life within the organization. The best opportunity to gain such an unvarnished view is to actually work there, perhaps as an intern or a part-time go-fer. If you can’t work there first, what can you learn about the environment from articles written about the company, from chat boards and social media? Can you informally meet any of the people who work there, as through social media or going to a bar at which people from the company unwind?

And don’t forget the company’s image. As mentioned, you will be at least partially identified with where you work and it will gradually become part of your self-image. Is it an image with which you will be comfortable? Do you relate to the industry, to the company’s image and practices? Is it an industry or company that you expect to be proud to work for, or may you come to resent or apologize for it?

All tough and very subjective questions. All important for such a big and important part of your life.

And Oh Yeah—What About the Salary and the Benefits? (Step 17)

I don’t necessarily mean to imply that salary and benefits should be at the bottom of your list of what you look for in a job. After all, you probably have student loans to pay off and would prefer to live on your own or with friends, rather than being forced to live in your parents’ basement. Besides, you’ve been scrimping for years living on an allowance or part-time wages and are ready to begin living. And let’s not forget the self-image boost associated with making big bucks out of school. Plus, depending on your job, you will probably have to buy an entire new wardrobe.

But all this notwithstanding, you should not let initial salary and benefits play a major role in your choice of your first career-track job. There is simply too much at stake to sacrifice the foundation of a multidecade career for a few more dollars in your first job. You should be much more focused on developing the skills, the experience, the relationships, the networks, and the reputation that will establish you as a high-value professional for whom employers will pay a premium in future jobs.

Still, you want to be fairly paid. Compensation should be appropriate for your job and competitive with that offered by other employers in comparable locations and industries. But just what is fair and appropriate?

Although you certainly want to be paid fairly, don’t let initial salary and benefits play a major role in your choice of your first career-track job. You should be much more focused on developing the skills, the experience, the relationships, the networks, and the reputation—benefits that will result in much greater pay in future jobs.

The aforementioned Accenture College Graduate Survey suggests that most aspiring grads have overly optimistic views of what their skills will command in the real world—and with what their money will buy.15 For example:

• Only 15 percent of pending 2013 grads expect to earn less than $25,000 a year, while one-third (32 percent) of 2011 and 2012 graduates who are employed report their current annual salary is $25,000 or less; and

• One-third (32 percent) of pending 2013 graduates plan to live at home after graduation, compared with 44 percent of 2011 and 2012 college grads who currently live at home.

You need to do some research to determine a fair salary for your skills and job. Take into account your major, your school, your ranking in your graduating class, the type of work experience you have had, your greatest accomplishments, in which industry and size company you plan to work, in what city or region of the country, and how do you come across in your interviews?

Luckily, you can find a number of guides to help with all of these variables. Your college may provide some salary information but you should probably view these data with a grain of salt, at least until standardized federal reporting guidelines are fully in place. Better yet are independent sources of salary information. The Bureau of Labor Statistics, for example, offers regular updates on salaries for a broad range of occupations, locations, and experience levels.16 So do commercial companies such as Manpower and PayScale17 (which also offer breakouts by college the employee attended). A number of industry-specific recruitment firms, like the Dice Holdings, provide hiring and salary reports for the technology, financial services, and oil and gas.18

The National Association of Colleges and Employers provides some of the most comprehensive information.19 It surveys employers, not just on actual salaries, but also on job offers. It shows both by discipline and subdiscipline, and provides ranges, as well as averages, the salaries, and numbers of people hired by each industry. It provides data for graduate as well as undergraduate degrees and an online tool that allows applicants to drill down into the data, such as by industry, region of the country, gender, race, and years of experience.

You also need to add benefits such as insurance coverage, 401k contributions, and vacation policies into your compensation calculation. And, if you are looking at a leading Internet firm, benefits such as free prepared meals, dry cleaning, and concierge services can provide tremendous value and make it much easier to handle long hours. You also want to learn the criteria and the schedule on which your performance will be assessed, and how often your salary will be reviewed and bonuses paid.

Where Do I Want to Live? (Step 16)

While I place this criterion last on the list of what you should look for in a job, it is certainly not because it is the least important. It is that location is so subjective that only you can decide the value that a job location has to you.

Perhaps location is irrelevant to you. You would be just as happy in Podunk as in New York City or willing to move anywhere for the right job. Or, you may want or have to remain close to your family. Then there is the other extreme. My wife and I—from the time we finished grad school till now—first chose the cities in which we wanted to live (Chicago, Washington DC, Boston, and San Francisco) and then looked for jobs in that location. In Chicago and Boston, we each found rewarding jobs in the fields in which we wanted to work. While we were less success in DC (due to government hiring freeze), we chalked it up to a learning experience and moved to Boston where we were much more successful. Then after starting our own company, we made another lifestyle choice and moved to San Francisco. Location was extremely important to us for our lifestyle and was at the top of our job criteria list.

There are, however, a couple of big caveats for those who want to make a lifestyle choice of where to live. One of the most important is to determine, in advance, whether the city offers sufficient job opportunities for people with your skills and interests. Bio-tech engineers may have scant choice of jobs in Bismarck, North Dakota. Well-qualified nurses or software engineers with up-to-date skills, meanwhile, may have options in virtually any city or community. More generally, fast growing cities, like Austin or San Francisco, typically offer more opportunities than those that are shrinking, like Buffalo and Detroit.

You should objectively assess your qualifications and prospects for getting the type of job for which you are looking BEFORE you commit to moving to a new city in which you don’t have some type of support network. In our case, we chose the city but did not permanently put down roots until we found jobs (which ended up being the prudent approach since we were unsuccessful in Washington DC). You may want to have an offer in hand before getting tied into a long-term lease or buying a house. But, if you do decide to move to a new city before you have a job, be sure that you have a financial cushion that will sustain you should you have trouble finding a job. Even better, having a working spouse or partner can provide not only financial support during this time but also the type of emotional support that can sustain you during a search.

What About Starting My Own Company? (Steps 15 and 16)

There’s always another option. Why subject your career to the whims of a manager or the fortunes of a large company when you can take charge of your career from the beginning? Or maybe you don’t have a choice. After a prolonged search, what if you come up empty?

You can launch your own business anytime during your career. Peter Thiel, as discussed in Chapter 9, insists that it is best to do so at the beginning of your career—before even going to college. Although a decision as to when to go out on your own is a very individual decision, it may be a necessary one, such as if you have been laid off at 50, and have no job prospects.

There are two primary ways of building your own company: You can start big, with a big idea, third-party capital, and a staff. Or you can start small, as with an individual product, consulting, or freelance business and then either remain small or grow (either self-funded or with third-party loans or capital). In either case, anyone who is highly skilled in any field for which other people (even one or two, if they are willing to pay a sufficiently high price) are willing to pay has the potential of starting their own business.

The good news is that the combination of inexpensive computers, the Internet, outsourced and cloud-based services, offshore freelancers, 3D printing, and even crowdsourced funding has slashed the cost of starting your own business. The bad news is that becoming an entrepreneur requires a number of skills that not everyone may possess. For example, going back to the Partnership for 21st Century Skills Framework discussed in Chapter 3, you need the productivity and accountability skills to set and meet your own goals and to plan, prioritize, and manage your work without guidance. You must also have the information, media, and IT skills to make use of the tools that are available; the communication skills required to promote and sell yourself, and your value-add to customers or clients; and the initiative, self-direction, and accountability to do whatever is required for the timely delivery and quality of your work. And you must have the perseverance that will be required to put in months of work with the hope of future gratification and the flexibility and adaptability to rebound from inevitable setbacks.

Then of course, there are the business skills (basic accounting, finance, marketing, sales, IT support, etc.) required to run a business—skills that can often be learned from B-school, a few community college business classes, books, the Internet, or one of the rapidly growing number of entrepreneurship classes and workshops discussed in Chapters 8 and 9. But don’t underestimate the amount of time you need to do simple things like troubleshooting a computer problem, invoicing, or even collecting money.

And speaking of money, don’t forget the money you’ll need to get the business off the ground. Even if you bootstrap everything, you still need to live until the business can sustain you over the inevitable lulls in your business. You also have to plan for the uncomfortable possibility that your business will not succeed20,21 and will have to search for another job. Again, having a spouse or partner who has a steady paycheck and can fund your basic living expenses helps. If not, you need to put aside money for a rainy day—probably at least a year of minimal living expenses. This, of course, becomes much easier after you have spent some time working, saving money, and lining up a revenue stream from a client or two before you give up the security of a paycheck.

As you probably guessed, I am a huge fan of starting one’s own business. After spending five years in a large company and another three in a small company, I decided it was time for a change. After weighing offers from a few companies, I decided to go out on my own. I personally found the experience, self-confidence, and the networks I built in my first two jobs to be extremely helpful in going out on my own. Moreover I loved the flexibility of being my own boss, of setting my own hours, and the rewards of building a company that was focused on my own vision and my own lifestyle.

Luckily I also had a trusted partner in this venture—my wife—who quit her consumer goods marketing job as my business really began to grow. She provided strong operational skills consisting of accounting, marketing, administrative, human resources, legal, and management services that I had neither the time nor desire to provide and—even more importantly—provided a valuable, trusted sounding board for big decisions. Although we both worked much harder and longer than we would have for any employer, we built a firm that allowed us to schedule our work hours to fit our desire to travel, to be in charge of our own destiny, and fund our retirements. Yes, we had many sleepless nights wondering how to meet our payroll, especially during economic downturns. But it was all worth it in the end.

Even if you don’t have to or want to start your own business out of school, remember that the era of lifetime jobs is over. An economic slump, a disruption to the industry, or any number of other circumstances may force your employer to let you go. And a sad fact about layoffs is that they seldom occur in a strong economy when companies are hiring. Or maybe you just don’t feel your company is the right fit for you or you have had it with your company and don’t have another job to go to.

Even if you never, ever plan to start your own business, you must ALWAYS be prepared to do so. In this era of uncertainty and reduced loyalty, you never know when you may have to do so.

No matter if starting your own firm is your own idea or is the only option open to you, just remember to always keep your options open, and keep your resume up to date, your network active, and your job search skills sharp. It will make it a lot easier to go out on your own. And, oh yes, work on developing the skills and the confidence required to start your own business, keep at least one year’s minimum expenses in reserve, and have the self-confidence and communication skills required to market and sell yourself and your unique value add.

Avoiding Career Regrets

Your career can be a source of great fulfillment. It can, as suggested previously, also be a source of frustration. In the spirit of learning from the lessons of others, Daniel Gulati, author of “Passion & Purpose: Stories from the Best and Brightest Young Business Leaders,” wrote a fascinating 2012 Harvard Business Review blog post titled “The Top Five Career Regrets.”22 It is based on an admittedly unscientific sample of 30 interviews with business executives who, from the outside, most would judge to be very successful. They revealed some of the frustrations that can come from not following your passions and from becoming locked into a career. Their five greatest regrets, along with some of my own embellishments, were:

• I wish I hadn’t taken the job for the money: This was, by far the biggest regret of those who ended up in high-paying but ultimately unsatisfying careers. As one investment banker said, “I dream of quitting every day, but I have too many commitments.” A consultant said, “I’d love to leave the stress behind, but I don’t think I’d be good at anything else.”

• I wish I had quit earlier: Almost all those who had quit their jobs to pursue their passions wished they had done so earlier. While a 2013 Gallup survey (p. 12) found that 70 percent of American workers are “not engaged” in or are “actively disengaged” from their work, and are emotionally disconnected from their workplace.23 A Deloitte survey, meanwhile, found only a miniscule 11 percent to be “passionate” about their work.24 As one who eventually made the jump to a more rewarding job explained, “You can’t ever get those years back.”

• I wish I had the confidence to start my own business: According to a 2012 Edward Jones survey, only 15 percent of those who have not started their own businesses believe they “have what it takes” to be an entrepreneur.25

• I wish I had used my time at school more productively: Gulati’s book research found that many of his interviewees wished they had thoughtfully parlayed their school years into a truly rewarding first job. After starting a family and signing up for a mortgage, many were unable to carve out the space to return to school for advanced study to reset their careers.

• I wish I had acted on my career hunches: Several individuals he interviewed discussed regrets as to not taking “windows of opportunity” in their careers that they viewed as too risky at the time.

Speaking from the standpoint of one who did not use his time at school productively, but who did act on his hunches and made the jump relatively early in his own career (at least early in my second career), I agree full-heartedly with Gulati’s rankings. However, I have absolutely no regrets about spending the time I did (five years and three years, respectively) at either of my two previous jobs as I learned much from each about myself, my interests, and what it is like to work in both large and small companies. Both provided invaluable experience and both helped me discover passions that I never imagined when I was in school.

Besides, I thoroughly enjoyed what I ended up doing in both of these jobs. Why? I subconsciously applied (before I ever heard) the maxim of Jim Spohrer, the IBM executive who encouraged me to write this book. That maxim: “the best jobs will be those that you make, not those that you take.”

The best jobs will be those that you make, not those that you take.

After beginning both my jobs in predefined roles—and demonstrating competence in each of the tasks I was assigned—I identified opportunities that I saw for the companies and persuaded my managers to allow me to run with them. In both cases, I was gradually allowed to reduce the time spent on parts of the original job that I did not enjoy (but had still performed diligently and well) and spent the vast majority of my time on projects (one in each job) that became two of the best learning experiences of my life, and two of my greatest passions. I ended up building my own company—and an incredibly fulfilling career—around one of these passions and never looked back.

Your first career-track job, as emphasized throughout this chapter, is a critical step in your long-term career. It will give you an opportunity to apply and hone the skills you have learned through your education to real-world needs. It will provide a unique opportunity to learn about yourself—what type of work you do—and do not—enjoy; what you are and are not good at and how to use your skills to deliver value in a differentiated way; what limitations you most need to address; and what type of groups and organizations you would most like to live in. Even more importantly—especially if you move to a new city—it will expand your horizons; expose you to new people, new learning activities, and cultural opportunities; and possibly even give you a new perspective on what you want to do with your life, not to speak of your career. Make sure that you take full advantage of this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.