Alternative Ways of Getting an Advanced Education

Steps 10 Through 14

College is completely unnecessary if you are really smart and driven . . . I think the evidence speaks for itself when you look at great companies that are being created, how many of those people actually finished college.

—Elon Musk

Founder of PayPal, Tesla, SpaceX

Key Points

• Many high-skill careers, including some that pay very high salaries, do not require college degrees.

• There are a growing number of ways of preparing for a high-value career, other than a four-year degree. Community colleges can directly prepare you for many careers or provide a low-cost entry into a four-year education.

• Apprenticeship, although underutilized in the United States, can prepare you for many lucrative trades and increasingly for some key office jobs.

• Some now contend that college degrees not only are not necessary for, but also may reduce your prospects of launching a successful business.

• Gap Year programs can provide valuable detours before or during college.

• Boot camps and MOOCs can complement or even replace formal education.

Some form of college degree, whether an associate, bachelor, or graduate degree, currently is and will continue to be the most common means of qualifying for a high-skill job. This is especially true in a period of “degree inflation,” when a surfeit of applicants for each position makes it practical for employers to make a degree a de facto requirement for jobs that don’t really require a formal classroom education.

College, however, is certainly not the only means of developing these skills. Many high-skill trades, and even white-collar professions, don’t really require degrees. These include:

• Traditional trades, such as carpentry and electrical wiring;

• “New Age” trades, such as CNC tool programming and operation and green energy installation;

• Artisan trades, such as making wine, cheese, and craft beers;

• Most sports and arts;

• All forms of sales, from consumer retail through many types of expensive and complex capital equipment and some professional services;

• Most IT disciplines, from technical support and website design through network and database administration and software architecture; and, of course

• The all-encompassing category of “entrepreneur,” everything from starting a corner store to running a franchise operation to launching the next big social media giant.

Apprenticeships are a time-honored way of preparing for a career in a trade. While these hands-on methods of teaching and learning are particularly entrenched in manual trades, they are also beginning to be used in more professional positions. What, for example, are medical internships and residencies, if not apprenticeships? Some law schools, as discussed in Chapter 8, are moving in the same direction, with proposals to make the third year optional and provide students with the opportunity to work under experienced lawyers, such as in providing legal services for underserved low- and middle-income clients.

Both colleges and apprenticeship programs, however, take top-down approaches to teaching: a professor or master effectively decides what the disciple should learn and feeds it to them. The professor and master then decides whether the disciple learned the required information or skills and can demonstrate that learning in a way the master approves.

One, however, can often develop skills in much less formal, more self-directed ways. In fact, those with experience, demonstrable skills, and recognized accomplishments in a specific field (not to speak of those with a friend or relative who can get the candidate in the door) can often trump a candidate with a degree (at least in fields that do not legally require degrees).

Such skills can be gained through hands-on experience, such as hobbies, summer jobs, or fellowships or even solely by reading. There are now a growing number of additional means of developing these skills in an informal, more self-directed way, and even of demonstrating the degree of proficiency you have achieved and of earning a certification that demonstrates that proficiency. And some of this can even be done without setting foot into a classroom or in some cases, paying a dime of tuition.

This chapter begins with a discussion of more formal alternatives to four-year degrees, including community colleges and, briefly, apprenticeships and how they are being extended into professions that have typically required a college degree. It then discusses some less formal education opportunities, including online courses and Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), certification programs, boot camps, and fully self-directed learning programs.

The Community College Option

College does not necessarily mean a four-year school. The United States currently has 1,167 community colleges (1,600 when branch campuses are included). Of these, 993 are public, 143 are private, and 31 are tribal schools.1 They enroll a total of 13 million students—37 percent of all U.S. undergraduates.

Although two-year colleges are often viewed as something of a poor stepchild to four-year colleges, they play five critical roles in U.S. educational system. They provide:

1. Developmental education, for high school graduates who are not academically ready to enroll in college-level courses;

2. Transfer education, for students that will transfer to a four-year institution to pursue a BS or BA degree;

3. Degree education, where students earn a two-year associate’s degree, with no current plans to attend a four-year school;

4. Continuing education, which entails noncredit courses for personal development and interest; and

5. Industry-specific and career education, including certificate- and noncertificate-based vocational classes and programs and in conducting the academic component of many apprenticeship programs.

Their role in developmental education typically entails picking up the pieces of the nation’s secondary school system by providing remedial courses to those who graduate from high school, but do not yet have the skills required for college. In fact, 59 percent of all community college students require at least one, and often many more remedial classes before they can begin taking courses that will count toward graduation.2 These schools also serve as a critical, low-cost “feeder system” for four-year colleges by providing a less rigorous entry into postsecondary education and a means of transferring credits that can be used to obtain a four-year degree. In fact, about 26 percent of students who start at community colleges move on to four-year colleges and 60 percent of them end up graduating.3

Many students, however, attend community colleges specifically to get two-year degrees. Associate degrees, after all, are the minimum educational requirement for the occupation that is projected to produce the largest number of new skilled jobs in the country—registered nurses.4

Community colleges, as discussed in my 2010 blog series on community colleges,5 also play critical roles as engines of social mobility. They (at least public, rather than private community colleges), for example:

• Have an open admissions policy, admitting anyone with a high school diploma or equivalent, regardless of grades;

• Cost an average of 63 percent less6 than those for public four-year colleges and 1/10th to 1/20th the cost of many private four-year schools;

• Cater to disproportionately higher percentages of ethnic minorities (40 percent of total enrollment) and first-generation college students in their families (42 percent);

• Are geographically widespread, with campuses or extension centers within an hour’s drive of more than half of the nation’s population (which also facilitates commuting, thereby reducing room and board expenses); and

• Provide greater flexibility than four-year schools in accommodating part-time students. Since many of these students have jobs, and many have families, almost 60 percent attend on a part-time basis.

These schools have typically been used largely by high school grads that didn’t have the grades or the study habits to succeed in a four-year school. However, the combination of skyrocketing tuition costs and the growing financial squeeze on middle-income families is prompting a growing number of applicants who are capable of university-level work, but are looking to reduce the cost of a four-year education. In fact, a 2011 Brookings Institution study rates community college education as the single best investment an individual can make.7 Its 20 percent internal ROI even beats out four-year degrees (15 percent) and more than doubles the return from the nation’s third-highest return investment, the stock market (7 percent). No wonder that the number of people enrolling in community colleges is exploding—up more than 20 percent between 2007 and 2011.

A 2011 Brookings Institution study rates community college education as the single best investment an individual can make—better than even a four-year degree or the stock market.

However, the vast majority of people who attend community colleges do not end up earning a degree: only 13 percent graduate in two years and 28 percent in four years. One reason is that community colleges attract and give chances to many marginal students who aren’t suited to or ready for college-level work.

Many community college attendees, however, never plan to earn degrees. They go to community colleges for nondegree vocational training, such as individual courses in an area in which they want to learn more, certificate programs, part of an apprentice curricula, or special programs run for local employers or trade unions. In fact, about 35 percent of those who complete their formal courses of study at these colleges earn certificates, rather than degrees.

Community colleges may be uniquely suited to such roles. They are often better attuned to the specific skills requirements of local businesses than are most universities and will often design classes in conjunction with, and serve as training arms for these employers. Such courses can take the form of contracted, employer-designed classes (such as for operating specific robots or computer numerical control, or CNC machines), formal certification programs which focus on a specific discipline (such as accounting, gerontology, graphic design, or CAD), or formal two-year associate degrees (as in management, nursing, culinary arts, and other career-based disciplines). Some schools even allow students to combine courses from multiple certifications into a formal degree program.

Governments also partner with private-sector employers to create vocational programs targeted at specific companies and industries. The State of Kentucky, for example, funded an initiative to help Bluegrass Community College build a replica of a car factory to train employees for jobs at a nearby Toyota plant.8 The San Francisco Bay Area Workforce Funding Collaborative is a partnership among local governments, business, and community colleges that train workers in areas including biotech, healthcare, and manufacturing.9 Boston’s SkillsWorks trains people to work in healthcare, hospitality, property services, automotive services, and green industries.10 New York and Chicago have recently created similar centers in transportation, construction, services, and manufacturing.

Graduating from such technical training programs can really pay off. A 2013 State of Texas study, for example, found that graduates of two-year technical programs have first-year median earnings of more than $50,000: $30,000 more than students who completed academically oriented two-year degrees and $11,000 more than graduates of bachelor’s degree programs across the state.11 A Colorado study, meanwhile, found that graduates of Associate of Applied Sciences (AAS) programs earn almost $7,000 more than graduates of bachelor’s degree programs across the state.12

A 2013 State of Texas studyfound that graduates of two-year technical programs have first-year median earnings of more than $50,000: $11,000 more than graduates of bachelor’s degree programs across the state

But for all of community colleges’ contributions and advantages, they also have their share of problems. The Department of Education, for example, found that only 31 percent of those who begin at community colleges earn their intended degrees or credential after six years: 27 percent of first semester students do not return for the second semester.13 Now, big cuts in state funding are forcing many of these schools to reduce the number of students they accept, eliminate classes, increase class size, and reduce quality.

These cuts have been particularly severe among California community colleges. After years of cost-cutting, they have been forced to eliminate 21 percent of their classes, making it difficult for students to get the courses they need to graduate. So difficult, in fact, that despite the systems’ open admission policy (any student with a high school diploma or GED is guaranteed admission), enrollment in California community colleges has declined by 16 percent—so much for the state’s educational safety net.

A growing number of four-year schools are now also beginning to offer two-year programs that provide some of the same functions as community colleges, albeit with fewer remedial courses and higher costs. These programs, often called “General Studies,” are generally designed for students who do not have the grades or the test scores, or are not otherwise ready for a more demanding four-year course of study. Schools such as Boston University, New York University, Texas A&M, University of Illinois, Emory University, Northeastern, and Columbia now offer programs that focus on interdisciplinary and foundational curricula delivered through smaller, more interactive classes with more personalized assistance. Most are intended as entry points for a four-year degree, rather than as a terminal degree. Many such programs guarantee graduates admission to the school’s four-year program. The Boston University program, for one, already accounts for about 15 percent of the university’s new undergraduate students.

Certification Programs and Apprenticeships

The majority of jobs open to those with no college education are low-skill, low-wage service jobs. However, a number of above average-paying mid-skill jobs don’t require a formal postsecondary degree. Most of these have their own informal or formal training programs.

Certificate programs, which provide formal recognition of the completion of a specified set of courses in a specific area, are the most common of these training programs, In fact, according to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), certificate programs were the fastest-growing segment of the higher education market from 2001 to 2010, with the number of certificates doubling. As of 2010/11, U.S. schools awarded more than 1 million certificates—more than the number of associate’s (942,000), master’s (731,000), or doctoral degrees (164,000) combined.14

These occupational certificate programs are available in hundreds of fields, from project management to nurse’s aide. While 33 occupations require certificates as a minimum qualification for entry, they are used in dozens of other occupations as a demonstration of experience and ideally, competence. The most common of these, as shown in a BLS report that looks specifically at certificate programs, are in various branches of healthcare, personal services, culinary services, and mechanic and repair technologies.15

There is also significant demand for certificates in various segments of law enforcement and firefighting (fields in which employment growth is expected to be slow) and many construction trades (some for which employment growth is expected to be strong). there is also growing interest in IT-related certifications. Fields such as PC repair, website design, and computer security are offering both good employment prospects and salaries.

Certificates can require anywhere from a few months to two years to earn, and cost anywhere from about $6,500 at a public college to more than $65,000 at a for-profit college. They also can potentially yield big rewards—or no rewards at all. The median salary for someone with a certificate in aviation, for example, is $66,000. Those with certificates in food services or cosmetology, on the other hand, have a median salary of less than $20,000.

Overall, a Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce study16 shows that certificates represent the highest level of educational attainment for about 12 percent17 of U.S. workers and that these people earn, on average, 20 percent18 more than those whose highest education level is a high school diploma. Then there are those in computer and information services.19 According to the study, men with certificates in this area earn an average of $72,498 per year—more than 72 percent of all associate and 54 percent of bachelor degree holders. Women do even better, earning more than 75 percent more than women with associate and 64 percent of those with bachelor degrees!

Certificates represent the highest level of educational attainment for about 12 percent of U.S. workers and that these people earn, on average, 20 percent more than those whose highest education level is a high school diploma.

Trade Apprenticeships

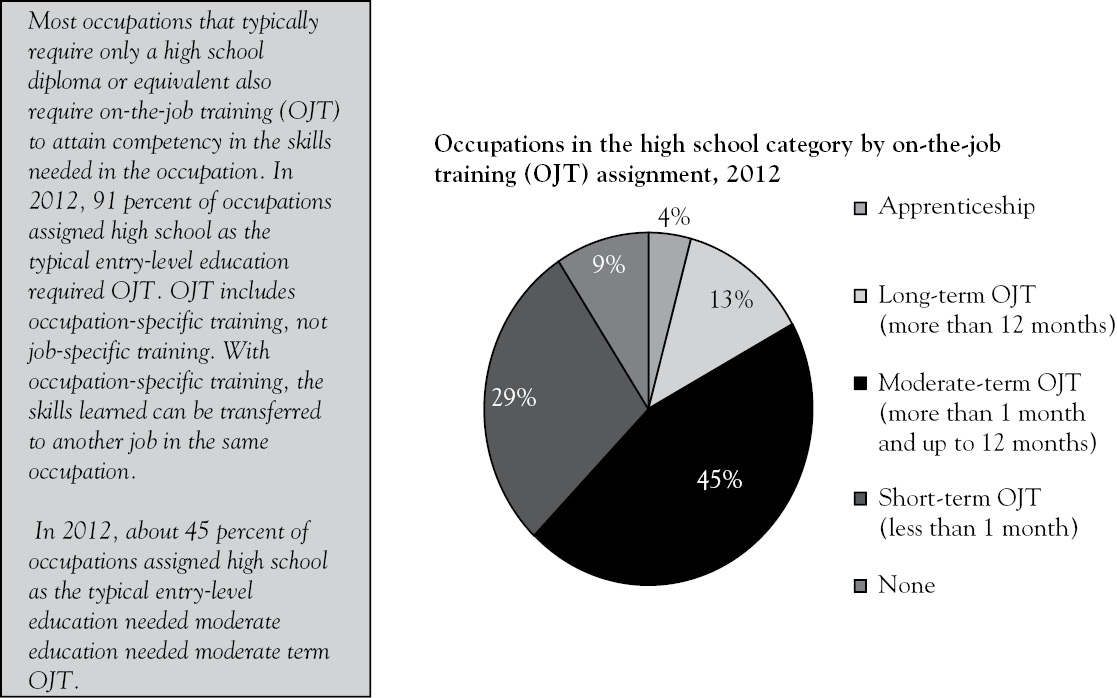

Although certificates are the most common form of nondegree vocational training programs, the vast majority of mid-skill jobs are, as shown in Figure 9.1, learned through on-the-job training. This training ranges from short-term, casual training for a couple of hours to much more formal programs of several years. The most formal programs—apprenticeships—typically combine formal classroom study (often at a community college and sometimes culminating in one or a series of certificates) with managed hands-on work. Some of these programs can be quite long and quite rigorous. The BLS, for example, estimates that apprenticeships typically entail at least 144 hours of occupation-specific technical instruction and 2,000 hours of on-the-job training per year over three-to-five years.20

Figure 9.1. On-the-job training requirements for high school occupations

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2012), p. 5.

Jobs that require formal apprenticeships are most numerous and best known in skilled manufacturing and construction trades, such as those for master electricians, plumbers, machinists, and welders. They are, however, also used in some government jobs (such as air traffic controllers and building code inspectors), skilled routine jobs (such as power plant operators and ship mates), creative jobs (fashion designers), green jobs (solar energy installers), and office jobs (paralegals). While many of these jobs offer decent pay (often starting about $15 per hour, with median pay typically ranging between $40,000 and $60,000 per year),some professionals, such as master plumbers21, pipe fitters, and welders,22 can easily earn six figures, with some claiming $200,000 per year (for those working on major projects with a lot of overtime).

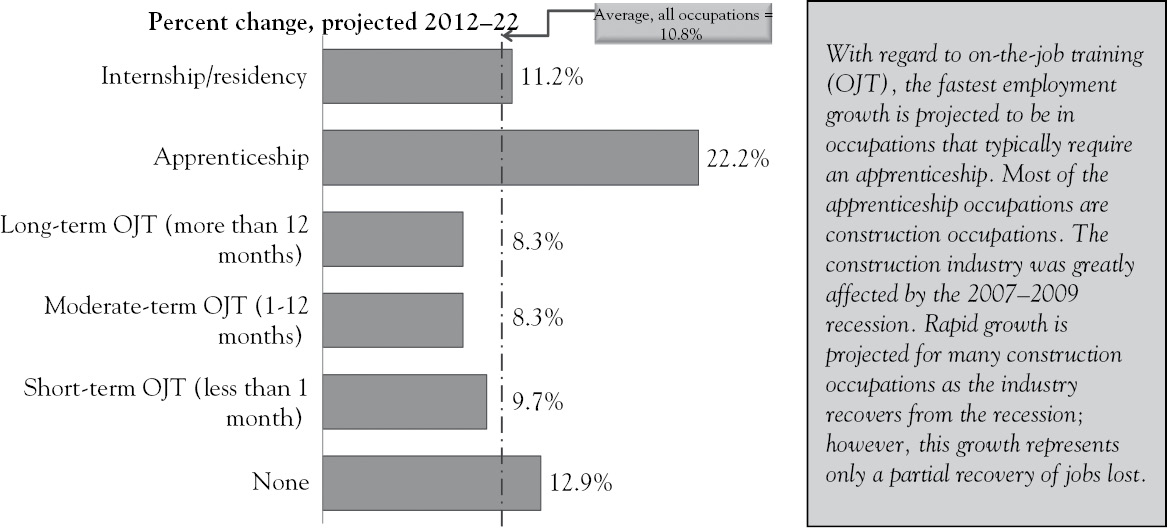

Workers skilled in many of these trades are also in high demand. As shown in Figure 9.2, for example, the BLS expects occupations that require apprenticeships to grow faster than any single category through 2022. A number of these occupations are expected to grow at more than 20 percent per year, and a few (such as brick masons and insulation installers) are likely to grow by more than 30 percent.

Figure 9.2 Growth in employment in occupations that require a high school degree, 2012–2022

Source: “Education and Training Outlook for Occupations, 2012–22” (2012), p. 4.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics expects occupations that require apprenticeships to grow faster than any single category through 2022.

Indeed, some of these jobs, such as those in advanced manufacturing and some high-skill construction fields, are desperately in need of skilled workers. A 2011 Manufacturing Institute survey, for example, found that 600,000 manufacturing job openings were left unfilled due to the inability to find qualified workers.23 And with pending retirements from a rapidly aging workforce, needs are likely to grow. The American Welding Society estimates that by 2020, there will be a shortage of 290,000 welders, inspectors, and teachers.24 Why are so many good paying and secure jobs going unfilled? Many young people are shunning factory-floor jobs in favor of office work, even when many of these office jobs pay less and are at levels below those for which they are planned and qualified.

Although apprenticeship programs play a very small role in the United States, they remain extremely popular in some European countries. They, for example, currently employ between 50 and 70 percent of all German, Swiss, and Austrian 15- to 19-year-olds and are generally viewed as comparable to college education.25 These programs are also gaining popularity in other European countries. The United Kingdom, for example, is dramatically expanding its program and about six other countries, including Spain, Italy, and Greece, have asked Germany for help in launching their own programs.

Apprenticeships are, in contrast, almost an afterthought in the United States, where they employ only 7.4 percent of all employed 15 to 19-year-olds and are accorded far less prestige than college degrees. In fact, while European programs are growing, U.S. programs have been shrinking, from 480,000 in 200826 to 330,578 in 2013.27

Bringing Apprenticeships into the Office

There’s another big difference between the United States and European programs. While U.S. programs are overwhelmingly in manufacturing and construction trades, European programs have extended into all types of occupations. For example:28

• Swiss programs now cover baking, banking, healthcare, retail, and clerical positions;

• British programs now include commercial pilots, lawyers, engineers, and accountants, with programs that are considered the equivalent of a college education.

Although U.S. firms employ few such white-collar apprenticeships, we are beginning to see a few, such as to train nursing assistants and supply-chain analysts. Computer skills, however, are by far the most common targets of such efforts.

Meanwhile, some state and local governments and private sector businesses are, as mentioned previously, also partnering to help design and fund community college-based apprentice programs. Just as importantly, a growing number of not-for-profit organizations are creating hybrid programs that use different combinations of academic and mentor-led on-the-job, hands-on training programs to prepare people for jobs in a broader range of occupations.

Year Up, for example, offers a one-year program that provides internships (rather than more formal apprenticeships) to high school graduates that not only encourages formal academic study but also requires participants to attend and earn graduation credits at local community colleges.

The first six months of the Year Up program consist of classroom education where students learn a range of technical skills (such as hardware support and repair, operating systems, software installation, security, and Microsoft Office) and soft professional skills (business writing, time management, communication and presentation skills, teamwork, etc.) in the classroom. The second six months entail internships at one of Year Up’s 250+ corporate and government partners, where they focus on either computer technology or financial operations. All students have an assigned advisor, a business community mentor and, if required, a private tutor. While Year Up works with a number of community colleges (which typically offer up to 23 college credits for completion of the program), it is now establishing more formal and collaborative affiliations—the first with Miami-Dade Community College.

Students develop marketable skills, earn college credits, and are paid a small weekly stipend. The greatest reward, however, is in Year Up’s 100 percent placement rate into jobs that pay an average of $15 per hour or $30,000 per year.

Year Up has graduated more than 6,000 students over its 12-year history and can currently accommodate up to 1,400 students per year across nine U.S. cities. In addition to its perfect placement rate, 95 percent of its corporate partners claim to be satisfied with the program.

Pathways in Technology Early College High School, or P-TECH, is the most ambitious of these programs. The program was formed as a joint venture among IBM, the New York City School District, the City University of New York, and the IBM Foundation, which provided the inspiration, shaped the curriculum, provided hardware and software, and provided the primary funding for the program. While it certainly combines academic education with a practical internship, it reaches all the way back to ninth grade to find primarily lower income students who will go through a six-year program, culminating in an associate’s degree in a computer-science-related field—and preferred consideration for a job at IBM. And all of this with no entrance exam, no tuition—and at no additional cost to the city’s education system.

P-TECH, which combines academic education with a practical internship, reaches back to ninth grade to find primarily lower-income students who will go through a six-year program, culminating in an associate’s degree in a computer-science-related field—and preferred consideration for a job with sponsoring companies.

The original Brooklyn-based IBM-sponsored high school, which provides an integrated curriculum across high school and community colleges, focuses on a broad range of STEM disciplines while also providing workplace skills in areas such as leadership, communications, and problem solving. Each student is assigned an IBM mentor who will work with the student, their teachers, and advisors to create an academic program that is tailored to the individual student and aligned to college and career requirements. The project-based curriculum will include many opportunities for exposure to the real world, as through guest speakers, regular workplace visits, internships, and apprenticeships.

Graduates receive both their high school diploma and an associate’s degree in applied science in either computer information systems or electromechanical engineering technology. While they do receive priority and extra consideration for an entry-level position at IBM, they are not bound to IBM. They can accept positions at other companies or transfer directly to a four-year college.

Since P-Tech is only in its third year, it is far too soon to assess how students will do when they graduate. Interim results, however, are impressive.29 For example:

• After two semesters, 72 percent of initial students passed both English and math Regents intended for 11th grade students and 80 percent passed after the third semester;

• After two semesters, 48 percent of students met the CUNY college readiness (CR) indicators and 50 percent did so after the third semester;

• After two semesters (9th grade), 25 percent of students exceeded the national average for 10th grade students; and

• Within three semesters, 48 of the 104 students in the first class had completed at least one college course at City Tech. Currently, 74 students (62 sophomores and 12 freshmen) are enrolled in at least one college course.

While the initial P-TECH schools have only about 100 students in each grade, the model was designed to be scalable and to operate with other corporate sponsors. It has already been replicated in eight schools, with plans for 29 more in two years: one in Chicago (with IBM as the lead industry partner) and four others in New York (with Cisco, Motorola, Microsoft and Verizon as lead partners, with another planned by SAP). New York’s Governor Cuomo has so-far announced plans for 16 P-TECH schools across this one state alone.30 The more recently created Chicago school (the Sarah E. Goode STEM Academy), meanwhile, is already ranked number four of 106 city schools in overall student growth and its students have earned an average of eight college credits.

Although IBM originally designed and founded the program, the company enlisted the Center for Children and Technology to produce a guide based on the P-TECH design and early years’ experience. The guide, STEM Pathways to College and Careers Schools: A Development Guide has already been used by the other above mentioned IT companies and is available to other companies, schools, and colleges that would like to establish their own private–public partnerships.31

Although current lead partners are all in the IT and telecommunications industries, the model is also intended to be applicable to many other fields including healthcare, advanced manufacturing, and finance.

Such programs are only the tip of what will hopefully become a growing trend. A number of the later-discussed Gap Year programs, for example, provide similar programs. The U.S. Office for Apprenticeships, meanwhile, is registering new programs in fields including information technology, healthcare, biotechnology, and geospatial technology.

Incenting Students to Drop Out and Start Their Own Businesses

Not all white collar apprenticeship programs require college. Many high school graduates (not to speak of some dropouts), who are more than capable of performing college-level work, have little interest in a formal college education. Perhaps they don’t enjoy or learn well from structured learning experiences. Perhaps traditional lectures bore them. Perhaps they are looking to design their own learning experiences, or maybe they just want to learn by actually doing real-world work, rather than just learning how to do it. Or maybe they can’t afford or justify the cost of a college education.

Whatever the reason, they are looking for an education, but on their own terms. Although people have always had options to college—from informal self-study and travel programs, to formal apprenticeships—the options for gaining a high-quality alternative education are exploding.

Some people certainly manage to do quite well without completing college. Famous dropouts, such as Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, and Mark Zuckerburg, managed to develop pretty rewarding careers without completing college. And, as discussed in Chapter 7, a growing number of IT companies are actively recruiting particularly promising students out of their early years of college, to learn in the real world.

Peter Thiel, a cofounder of PayPal who himself had a sterling education (Stanford BA and JD), has become the de facto champion of the non-college movement. He has vociferously denounced college as a waste of time and money and urges students to forgo formal education in favor of real-world learning experiences. In fact, he feels so strongly that he created a fellowship program that provides a no-strings grant of $100,000, plus guidance, mentorship, and access to professional networks to 25 students per year (60 since the program was started three years ago) who eschew college in favor of developing their own business ideas.32

Its goal is to select the type of particularly high-potential young adults that would have normally gone to highly competitive colleges and provide them with an accelerated, nontraditional path to creating their own companies or launching into other types of high-power careers.

But, for all its publicity, the Thiel model also has some high-profile critics. Tech entrepreneur turned academic Vivek Wadhwa, for example, claims that Thiel fully vets and carefully selects students who had already been accepted at elite colleges, puts them through a rigorous qualification process, and then showers the select few with the type of mentors and professional guidance that incubators provide—plus a lot more money—but with none of the results.33 As he sees it, for all the money and guidance, the program has produced a number of flame-outs, but no significant successes. He also questions the social responsibility of providing a couple dozen high achievers, who are already well on track to a successful career, with a no-cost, no-risk opportunity to accelerate their rise, rather than giving hundreds of disadvantaged youths the opportunity to climb into the middle class.

Self-Directed, Semistructured Gap Year Programs

Although the jury is still out on the benefits of the Thiel Fellowship, a few other nonprofit organizations have bought into the broad idea of alternative educations and are developing hybrids between the apprenticeship and the Thiel entrepreneurship models. Some of these programs are positioned as alternatives to college. Some as semistructured Gap Year programs for those looking for a year of experiential education to, as the American Gap Association puts it, “increase self-awareness, challenge comfort zones, and experiment with possible careers.”34

While all Gap Year programs are different, they are typically intended to help participants increase self-awareness, challenge comfort zones, and experiment with possible careers.

Such programs, which can be entered into between high school and college or as a break between years in college, are becoming increasingly popular. The Association, which promotes and accredits these programs, for example, believes that about 40,000 Americans now participate in them. It claims that about 90 percent of participants return to college—typically with more direction and motivation.

UnCollege, which was founded by one of the first Thiel Fellows, provides one such program. It provides free advice and guidelines for anyone looking to design their own alternate education programs, either as an alternative or as a supplement to college.

It is intended to help nontraditional learners identify their own passions and pursue their own paths by helping them define their goals and the steps for achieving them. It guides participants through a process of creating their own individualized learning plans and helps them identify, prioritize, and pursue the life experiences that will allow participants to achieve their goals. It also helps in more concrete ways, such as by helping individuals craft their own elevator pitches, develop strategies for building mentor networks and online curriculum vitae that will demonstrate their competencies. UnCollege contends that this process helps fuel an individual’s passion; develops their organizational, creative, and self-motivation skills; bolsters their self-confidence; and burnishes their reputation on the basis of real world, rather than (or in combination with) academic accomplishments.

Information and advice on how to do this is provided in Dale Stephens’ book, Hacking Your Education, on the organization’s website, and through its blog and weekly newsletters.35 All promote a self-directed approach to learning in which each student (or actually, nonstudent) decides what he or she wishes to learn, actively seeks out the sources and activities to facilitate that learning, and then let the world, rather than a designated master, determine “the grade.”

Although initially designed as an alternative to college, UnCollege has added a more formal, year-long blended learning and internship program called Gap Year.36 Gap Year, like the Thiel Fellowship (and very unlike Year Up and P-TECH, both which are open to all applicants) carefully vets and accepts only select individuals—particularly those with “extraordinary intelligence,” “unstoppable motivation,” and “unflappable integrity.” Unlike Thiel, however, UnCollege does not give participants money. It charges tuition for a relatively informal education program combined with internship or apprenticeship opportunities that it contends will be more effective at preparing students for careers than will college. The year-long program is divided into four, three-month phases:

1. Launch, which consists of sessions, workshops, roundtables, and discussions designed to help participants develop meta-learning and technical skills, meet mentors, and design their own learning programs and line up their internships;

2. Voyage, where participants will live for three months in a country in which they do not know the language and work in whatever area they believe will most challenge them and help them grow;

3. Internship, with any company or organization that will help advance the individual’s specific learning objectives. (UnCollege will help the participant decide on and line up the internship and provide support over the three-month period); and

4. Project, any type of project with a tangible deliverable, which someone will pay the participant to complete, such as a book, an art exhibit, a business plan, or a product.

Gap Year, which costs about $15,000, also includes room and board at a shared house, three months of expenses for living in another country and assistance through all phases of the year-long program. The primary goals are for participants to leave with increased confidence in their own abilities, a range of new skills, a digital portfolio that showcases these skills, and a plan for what they will do next. Most importantly, participants should leave with “the skills and mindset required to build multiple income streams” (such as getting job offers, becoming a freelancer, or creating their own companies)—anything to provide the financial independence that individuals need to remain in control of their own careers and lives.

Enstitute, a two-year program based in New York, is something of a cross between structured white-collar apprenticeship programs and the much less-structured self-directed learning opportunities offered by Thiel and UnCollege. Like Year Up and P-Tech, it is preparing people for entry into mid-skill careers. But like Thiel and UnCollege, it specifically selects the type of people who have demonstrated the skills to succeed, provides them with a relatively unstructured educational program, and provides them with opportunities to develop their skills in apprenticeships.

Enstitute partners with private companies to create apprenticeships in four areas: technology startups, digital media, advertising, and nonprofit or social good. It targets bright, ambitious, entrepreneurial young adults who are either not interested in college, tried college and dropped out, or graduated but are looking for alternatives to graduate school.

The first year consists of Enstitute’s own semiformal, modular curriculum that combines online and classroom business courses in disciplines including marketing, sales, business development, operations, human resources, business technology, and design. It drills down into a number of technology areas including systems architecture, front-end systems and user interfaces, programming, and application development and also provides some high-level online academic courses in areas such as English, sociology, and history. These classes are complemented by guest lectures, workshops, and regular (every six weeks) writing assignments. The second year consists of a 40 hour per week apprenticeship, where the student works under a mentor at a sponsoring company.

Although graduates do not receive a diploma, they do compile their own digital portfolios, with examples of the skills they developed, business development deals they’ve closed, marketing materials they’ve created, and products they’ve built. They also receive between 5 and 10 recommendations and, ideally, an offer from the company under which they apprenticed.

While the program just began this year with its first class of 11 students, it plans to expand over the next several years. Students will pay $1,500 in tuition per year (not including room and board). They will, however, receive $1,600 per month stipends during the apprenticeship year.

A growing number of colleges are coming to recognize the value of such programs, often seeing returning students as being more focused and motivated than those who go straight from high school to college. Some not only accommodate students’ gap years, they even help cover some of the costs.37 Schools including Princeton, University of North Carolina, and St. Norbert College now offer formal programs that allow newly accepted students to defer admission for a year, and will subsidize part of the costs of structured programs, such as volunteering for an NGO in areas such as education, economics, health, and the environment. Tufts University goes further than most, paying up to $30,000 to cover participant’s airfare, housing, and visa fees.

The Online Education Option

Regardless of which path you choose to developing the skills you will require for your career, that path will increasingly entail some form of online learning. Although computer-based training programs and tests have been around for decades, the explosion and increased sophistication and capabilities of online courses and testing promise to greatly expand the opportunities for learning new skills and qualifying for new jobs.

This revolution is being created by the explosive growth of MOOCs, which are teaching everything from remedial reading to astrophysics. Individuals can listen to lectures, test their knowledge, and even participate in virtual learning teams in which they can question teachers from any computer, at any time that suits their needs. Some of these courses issue certificates of successful completion and even college credits.

MOOCs, which teach everything from remedial reading to computer programming and existentialism, allow participants to listen to lectures, test their knowledge, participate in virtual learning teams typically for free), and increasingly earn very low-cost certificates, college credits or even degrees.

Online education programs first emerged several decades ago, being used first in in-house training programs and then by for-profit colleges. Their recent popularity explosion, enabled by Internet and broadband connections, was literally born in the closet of ex-hedge fund analyst, Salman Khan, who created the online Khan Academy which is now accessed by about four million people each month. Stanford professor Sebastian Thrun then fuelled the inferno with his massively popular online course on Artificial Intelligence, which registered more than 160,000 students.38

There are now thousands of online courses on every imaginable subject, offered by everybody from self-styled gurus to top professors from the most renowned colleges in the country. In fact, dozens of tier-one universities, including Harvard, MIT, University of Pennsylvania, and Stanford, are now producing online courses that are being offered by big, high-budget consortia and venture fund-backed companies such as Coursera, Udacity, Udemy, and edX. Graduate business schools are also getting into the act. Although a number of top schools offer free introductory or hybrid programs, two top 20 Schools, Indiana University’s Kelley School and University of North Carolina’s Kenan-Flagler School, now offer fully accredited online degrees.

And the best part—most of the noncredit courses are free. This being said, a growing number of those who complete the required coursework and pass proctored exams want certificates to enhance their employment prospects. While most such certifications currently cost $50 or less, these costs are likely to increase significantly as courses and programs become accredited.

Although courses are becoming available in every field, from calculus to existentialism, the majority are focused on teaching the type of hard skills (as in math, science, and technology) that are most suitable for objective, automated grading. In many ways, this is a great place to start. After all, as discussed in Chapter 3, while computer skills are becoming a basic form of literacy, they are formally taught in only about 10 percent of U.S. high schools.

This borders on criminal. First, virtually every productive member of 21st-century society will require these skills. Second, while BLS estimates that the economy will produce 120,000 new jobs for people with computer science degrees in 2013, few students leave high school with more than basic computer skills or plans to develop them. U.S. colleges, meanwhile, are expected to graduate fewer than 52,000 people with the backgrounds required to fill the millions of jobs that will require coding skills.

Worse still, the United States is lagging far behind many competitive nations in training their youth. Computer science has been a standard part of the high-school curricula in countries including Germany, Denmark, Israel, and New Zealand for more than a decade. England, meanwhile, is now incorporating it into its standard primary school curriculum!39

Therefore, it is not surprising that a number of for-profit and nonprofit organizations are rushing to teach these skills. Organizations such as Codeacademy, Treehouse, Code.org, Pragmatic Studio, and dozens of others now offer individual courses, full online curricula, and in some cases, formally structured boot camps around all types of IT disciplines.40 They allow participants to develop skills, and increasingly earn formal certifications in high-demand IT skills such as software development, website design, and computer analytics.

A growing number of organizations are aggregating IT and other types of career-focused courses from thirdparties. SkilledUp.com, for example, provides access to 113,000 courses (ranging from free to $250): primarily skills-based courses in areas including IT, graphics design, finance, and marketing. Apollo Education Group (University of Phoenix) is launching a new online education marketplace called Balloon.41 It will list open jobs and their skills requirements and refer people to a catalog of about 15,000 online technology classes that will help students develop the type of skills required for these jobs and earn certificates that demonstrate completion.

Google, meanwhile, is already partnering with Udacity to bring its third-party developer programs online and to “fast-track best practices at a large scale.” A number of other tech companies, such as Microsoft and Adobe, are preparing similar MOOC offerings, many of which will result in certifications on the vendors’ products. AT&T, meanwhile, is partnering with Udacity to train not third-party developers, but potential employees. Its NanoDegree program allows individuals to take classes, designed around AT&T’s specific products and methodologies (for $200 per month) to qualify for entry-level positions in the company’s IT department.

These are all examples of using MOOCs to help people learn a relatively narrow set of skills that culminate in credentials that qualify graduates for a specific job—sometimes within a specific company. They could also augment or take the place of some companies’ work with community colleges.42 While most such classes currently focus on IT, and especially software development skills, they will soon expand into other areas including energy, healthcare, and manufacturing. Most MOOC courses, however, will continue to focus on teaching a relatively narrow set of skills that culminate in credentials that qualify graduates for a specific job.

Entrepreneurism is becoming another popular field for online study, with a number of courses and predesigned curricula designed around the needs of those looking to start their own business. Examples include Udacity’s How to Build a Startup, Y Combinator’s Startup Library, and Stanford University’s E-Corner. A number of other programs and books teach many of the concepts learned in business school, without the formal B-school experience.43

But while MOOCs are still largely experimental, they are beginning to be incorporated into formal college, and even a few high school curricula. High-school adoption may be very slow and limited, but some teachers have begun to assign Khan Academy modules as homework and use class time to review and help students who have problems with the material.

Colleges, however, are moving much more aggressively. Although few of the leading universities that are putting many of their courses online offer college credits for their courses, MIT, in conjunction with EdX, plans to offer a line of low-priced (currently from $275 to $425) XSeries online course sequences that will allow students to earn certificates in subjects including computer science, supply-chain management, and aerodynamics.44

A growing number of other colleges are beginning to offer such courses for actual college credit. Some for-profit schools, such as the University of Phoenix, have been doing so for years. Now, a few public colleges such as Washington State, some University of California schools, and Arizona State have begun to integrate online courses into their curricula. Arizona State, in fact, has entered into an agreement with Starbucks, under which the coffee house will pay half tuition for those of its half-time to full-time employees who study for an online bachelor’s degree from Arizona State University (and full tuition for those who complete the degree after already having half the credits needed to graduate.) Although many companies offer tuition reimbursement, this program is unique, partially compared with fast food industry standards and partially due to the fact that employees are eligible for assistance from the day they join and are free to leave immediately after they complete their degrees.45

Georgia Institute of Technology, meanwhile, became the first major university to offer a formal online degree, a Master’s in Computer Science.46 The program, which will cost about $6,800 for in-state students (compared with $45,000 for an on-campus master’s degree), will include access to online tutors, office hours, and other support. It will also require proctored exams. The University will offer these online courses and completion certificates free for those not seeking a degree. The University of Florida is likely to follow with an online bachelor’s degree now that the state legislature directed it to offer such programs at about $4,700 for in-state residents, about three-quarters the cost of in-state on-campus tuition.

However, many question whether MOOCs are ready for prime time. Course and exam quality, not to speak of the meaning or value of credentials, are still inconsistent. Completion rates remain below ten percent, with college graduates (presumably due to their existing knowledge base, experience in self-directed study, and motivation) being the most likely to finish. As of now, few courses provide meaningful classroom-type interaction, or an ability to communicate with professors. Providers, meanwhile, are still experimenting with methods of teaching and grading (especially of softer subjects) and of ensuring that people who pass online exams are who they say they are (rather than a friend who takes the exam for them). Few certifications, therefore, yet carry much value and few universities—including those whose professors create these courses—yet offer credit for completion.

edX, therefore, suggests that colleges take a more cautious, “blended” entry into the MOOC world, which would combine traditional and online learning with work experience. Its recommendation: one year of introductory MOOC learning, followed by two years at a physical university, followed by a fourth year that combines MOOC courses and part-time work.47

Although a few colleges already offer full MOOC degrees, edX recommends a blended approach consisting of one year of introductory MOOC learning, followed by two years at a physical university, followed by a fourth year that combines MOOC courses and part-time work

But despite the gaps and the questions, MOOCs are likely to revolutionize virtually every segment of the education market, especially postsecondary. Self-directed learners will have access to whatever courses tickle their fancy. Certificate courses will increasingly move online and gradually gain credibility as the industry begins to agree on standards (such as Mozilla’s Open Badges) to confirm the validity of such courses.48 They will also be increasingly incorporated into college and apprenticeship programs and, as we are beginning to see, form the foundations for entire college degree programs.

They, as mentioned above, are even beginning to creep into some top-tier graduate business programs. While University of North Carolina and Indiana’s B-schools already offer online degrees, the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School uses its MOOC to attract, and ideally recruit, nontraditional business students (from emerging countries, minority groups, first-generation Americans, etc.). Although completion rate is only about five percent, studies show that many participants are more interested in learning than they are in earning certificates.49

Harvard Business School, meanwhile, is introducing a trial, MOOC-based pre-MBA program called Credential for Readiness (CORe) which provides basic courses intended to help liberal arts graduates develop skills in areas such as accounting, analytics and economics. Tuition is expected to be about $1,500 and culminate in a three-hour exam, a grade and a certificate.50

MOOC courses will also play a huge role in enabling another critical need of the 21st-century workforces—lifelong learning. They will facilitate formal and informal updates of work skills, provide new opportunities to pursue new hobbies, or prepare oneself for a new job or even a totally new career. True, some of the challenges confronting MOOCs are still to be resolved and it may take time to achieve the type of results that will persuade employers that MOOC graduates actually possess skills comparable to those of graduates from traditional schools and programs (see, however, the latter section on certification). But with all the attention, money, effort, and prestige being invested in these courses, it is almost certainly a matter of time before they gain more credibility.

Post-Graduate Boot Camps

A large—and growing—number of classroom or internship-based supplemental education programs are intended to help college graduates supplement their education with certificates that demonstrate specific types of marketable skills. The most popular programs focus on specific skills that will equip graduates for entry-level positions in a broad range of industries. Among the three most popular of these disciplines are:

• Entry-level programming which teaches a working knowledge of particularly popular programming languages, such as Ruby, JavaScript, and C++.

• Business basics for nonbusiness majors of fer college graduates (primarily those with bachelor’s degrees) a high-level working understanding of the type of business terms, functions, and skills that are required to get an entry-level job in a company. Courses may cover areas including finance, accounting, marketing, business communication, organizational behavior, business ethics, and corporate social responsibility.

• Entrepreneurialism, for those planning to launch their own business or to get a job in a start-up. Programs typically include classes on tuning business ideas, writing business plans, and developing pitches to lenders and potential investors. Some of the more in-depth programs also provide basic courses in finance, marketing, website design, and a number of other skills that will be required to manage your business.

A number of classroom or internship-based boot camps help college graduates supplement their education with certificates that demonstrate specific marketable skills in areas including programming, business basics, entrepreneurialism and a growing range of specialized topics.

Coding boot camps are among the most common of these programs, accepting students with little or no programming experience. In return for three weeks to six months of your time and $8,000 to $20,000 in fees, they promise to turn you into an entry-level coder who can command starting salaries of $60,000 or more.

Since I discussed online coding boot camps previously, I’ll just briefly mention some of the on-site programs here.

On-site boot camps, from organizations such as General Assembly, Dev Bootcamp, Hack Reactor, and App Academy, can last anywhere from a few weeks to up to six months and cost between $3,000 and $20,000. The longer, more expensive programs often provide premium services, such as personal mentoring and job search assistance and can result in certificates. Some can also be incredibly selective in whom they admit, with some claiming acceptance rates of three to five percent—similar to or even lower than those of Harvard or Stanford. Those who make it into and through the programs can reap some big rewards. Most schools claim placement rates of well over 90 percent and average starting salaries of more than $100,000 in high-demand markets such as the San Francisco Bay Area, New York, Boston, and Washington. In fact, some camps, such as App Academy, are so confident of their alumni’s ability to get good jobs that they will forgo tuition in return for 18 percent of a graduate’s first year salary.

This being said, there are, so far, no established standards for assessing such claims and some boot camps are retreating from claims that they can turn novices into professional programmers in the equivalent of one semester. Some are expanding their curricula and some, such as Dev Bootcamp, now require students to complete a nine-week preparatory course before beginning formal classes. They are also retreating from their claims of producing “professorial programmers” with statements that although their programs will prepare graduates for entry-level jobs, mentoring and ongoing education will be required to advance in their careers.51

Business Basics boot camps are available from a number of schools and for-profit organizations and are intensive, multiweek (typically multithousands of dollars) programs. Many established business schools and colleges, such as Berkeley Haas School and Dartmouth’s Tuck School of Business, offer business basic programs to all qualified applicants (remember also the above-mentioned Harvard Business School MOOC-based CORe program). Some liberal arts schools, such as Middlebury College, meanwhile offer such programs as options to current students. A number of independent boot camps, including those from Fullbridge and Business Boot Camp, are intended to provide skills that can work in any type of company. Others, like StartUp Institute, offer a boot camp specifically designed to help people get jobs in start-up organizations. While it does provide a core curriculum, it focuses on preparing individuals for specific positions, such as in product design, web development, technical marketing and sales, and account management.

Entrepreneurialism boot camps are especially popular among graduates directly out of school, corporate employees looking to launch their own business idea, or established professionals, such as doctors and lawyers, who are looking to transition from a larger firm to private practice. The Kaufman Institute, a nonprofit foundation dedicated to encouraging and facilitating entrepreneurship, is the largest player in this market. Its FastTrac programs, which are offered by a number of colleges across the country, are available in three different flavors: one for launching a new business; one for growing an existing small business; and one specifically targeted at the specialized needs of technology startups. As discussed in Chapter 8, a number of colleges and graduate schools already offer majors, minors, and specialized graduate degrees in entrepreneurship. A number of business schools, such as Babson and Syracuse University’s Whitman School, also offer broad-based entrepreneurism boot camps. There are also a rapidly growing number of specialized programs. These include:

• Wisconsin Entrepreneurial Bootcamp is designed specifically for STEM majors;

• Social Enterprise Bootcamp is intended to help founders of for-profit and nonprofit businesses develop socially responsible businesses;

• Starter School combines coding and entrepreneurism boot camps into a program designed to prepare people to start their own software company; and

• Syracuse University’s Whitman School and Purdue’s Krannert School offer boot camps designed specifically for veterans with disabilities.

Speaking of specializations, Claremont Graduate University offers a boot camp specifically designed to help job hunters; General Assembly has one that focuses specifically on helping individuals optimize the business use of social media; and Northwest Michigan College has one to teach film production. Meanwhile, schools such as Hunter College and Northwest Michigan College offer programs focused on those looking to start software-as-a-service, bed-and-breakfast, and personal training businesses. John F. Kennedy University offers them in sports psychology and in exercise and sport performance.

Whatever set of skills you think you may need, there’s probably a boot camp that will offer to help you develop them. And if there isn’t one today, there probably will be tomorrow.

Credentials, Certifications, and Trust

High school degrees and college degrees are credentials. Unfortunately not all degrees are created equal. Some high school graduates may be unable to write (or in some cases, even read) a coherent sentence. Nor are all college educations equal. Even so, in order to receive and maintain certification, all schools must meet established minimum standards. Moreover, colleges are well enough established that you can often find some form of objective, third-party ratings not only for the school but also for specific departments. And, as discussed in Chapter 8, the Department of Education is also working on its own set of college ratings.

Although such ratings may or may not provide meaningful surrogates for the quality of education or the ability of an individual with a specific degree in a specific major to get a job and command a living salary, they do little to help employers determine whether a particular graduate has the type of real-world skills required to perform specific jobs.

And if it’s this hard to measure the skills of a college graduate, how do you measure those of a “graduate” from less formal programs, such as apprenticeships, online courses, and boot camps? This is a huge gap that must be filled if employers are to accept these less formal programs as valid alternatives or supplements to college degrees.

A number of trades and professions do require state certifications that assure at least some base level of knowledge. This is true for professions from plumbing to real estate and insurance sales, to nursing, and law. However, many courses or programs offered in areas such as software development, web design, marketing, or business communication, much less for entrepreneurism, have objective standards.

Some large employers already assess individuals through their own proprietary tests, but if these less formal educational programs are to be viewed as serious alternatives to a formal education, there must be some form of standardized measurements or certification. This is especially true if individuals hope to demonstrate mastery from a combination of courses and hands-on learning experiences from different sources.

Although we have a long way to go, some progress is being made. Mozilla Open Badges, for example, is an open software standard that is intended to provide objective verification of the skills learned from and achievements made in different programs. More importantly, it allows students to combine multiple badges from different sources (such as colleges, professional bodies, community learning organizations, boot camps, and online initiatives) together into a single body of learning.

But testing for specific functional skills is one thing. Testing for much more abstract concepts such as critical thinking, creativity, and teamwork is altogether different. Although interviews, writing samples, and references can help address these needs, we need a more standardized, more objective means of comparison—especially when a potential employee has cobbled their own education from a broad range of traditional sources.

There are a number of attempts to do just this. The Lumina Foundation is offering a $10,000 award for ideas as to how to quantify the impact of certificates from a range of nontraditional sources. ACT’s Career Readiness Certificate is trying to provide an objective measurement for certifying the combination of cognitive and soft skills required to predict workplace success. Educational Testing Service offers certificates for those who score well on proficiency profile tests designed to assess critical thinking, reading, writing, and math skills. Meanwhile, CAE’s Performance Assessment Test, which is currently being used by more than 700 colleges, claims to measure critical thinking, problem solving, scientific and quantitative reasoning, writing, and the ability to critique and make arguments.

All of these tests can be taken by and certifications issued to anybody, regardless of how or where they learned their skills. Although there’s still a long way to go before employers will begin to accept such certifications as measures of workplace success, progress is being made. Once one or more of these or other assessments begin to achieve critical mass, the still sharp distinctions between formal and informal learning programs will begin to fade. Until then, they can still provide some level of objective evidence that you have taken your learning seriously and that you value the type of skills that employers are looking for.

The Potential of Alternative Education Programs

There is no question, at least in my mind, that some form of college (two-year, four-year and for some, graduate degrees) will continue to be the primary and most popular path to the type of high-skill job that will maximize your chances of gaining control of your own career.

That being said, a formal college education is absolutely not the only path. For example:

• Community colleges play five incredibly valuable roles in providing postsecondary education. But given their low completion rates, they may be spread a bit too thin. They, however, face an even more immediate challenge—maintaining even current standards in the face of big state government funding cuts.

• Apprenticeships will continue to be an important semistructured alternative; not only for traditional trades but also increasingly for the type of mid-skill white-collar jobs that will provide many with an entry into occupations that would have not normally been open to nongraduates.

• Experiments such as Year Up, UnCollege, and Enstitute are certainly interesting and bear watching. If they are found to be effective and scalable, they have the potential of preparing people for, or serving as alternatives to, college. This being said, public–private approaches like P-TECH (again, if proven effective and scalable) have the potential of revolutionizing education and lifting thousands out of a life of poverty into secure jobs, higher education and quite possibly, into executive ranks or entrepreneurial careers.

• Self-directed learning programs like the Thiel Fellowships, and to a somewhat lesser extent, UnCollege are better suited to a smaller number of high-potential, self-directed high school grads who either do not need college or who can benefit from experience before college.

• MOOCs and boot camps can provide entry-level or supplementary skills. MOOCs, in particular, have potential of being game-changers, totally transforming the education system—initially among tier-two and -three colleges, and potentially, even secondary-level school.

This all leads to the next question. Once you decide the type of career you are looking for and develop the skills and earn the credentials that are needed (however and wherever you develop them), just what type of job and what type of employer will be best suited as a launch pad for your career? If you follow the plan laid out in this book, chances are that you end up with at least one offer for a meaningful, career-track job. Ideally, you will find yourself in the enviable position of having to choose among offers. Which criteria should you use to plan you search, select your target employees and assess which job is best for you? These and a number of related issues are addressed in Chapter 10.