Chapter 14. Surreptitious Code and the Law*

Fred H. Cate

14.1 Introduction

Computer users increasingly confront software that collects information about them or asserts control over their computers without their knowledge or consent [116]. Whether labeled spyware, adware, ransomware, stealware, keyloggers, trojans, or rootkits, they have in common the fact that they are installed and operate without explicit user knowledge or consent [138]. Unlike earlier forms of code-based attacks that operated without any human intervention, these programs frequently exploit human credulity, cupidity, or naiveté to persuade or trick the computer user into downloading, installing, or executing them.

We often describe these programs collectively as “malicious code” or “malware,” but these labels may not be accurate. For example, adware can improve the relevance of advertisements that users see and contribute to making certain programs or information available at no or low cost. Cookies can offer the same benefits as well as enhance consumer convenience and recognition when visiting familiar web sites. Spyware may include programs that allow parents to track their children’s computer use or facilitate remote diagnostic testing of computers. These uses are far from malicious, but the code may nevertheless operate without the knowledge of the computer user. Moreover, our current labels are not particularly helpful, because they often reflect judgments that are subjective and usually reflect a conclusion rather than aid in reaching one.

Determining whether programs are malicious—or illegal—often depends on a variety of factors. These include how the user obtained the software; what, if any, information was communicated to the user; whether that information was accurate and complete; which actions the user took in response; how the software operates; what effects it has on the user and the user’s computer; whether it can be removed or disabled and, if so, how easily; and even in which state the user resides or the computer is located.

Finding the boundaries of what is lawful is made all the more difficult by the fact-specific nature of these inquiries, the variety of potentially relevant laws and precedents, and the speed with which new applications are evolving. Mistakes and uncertainty about where those boundaries lay pose real risks for programmers, users, researchers, and institutions.

These risks are exacerbated by our changing understanding of consent, including what is required for it to be legally binding. Historically, it was usually possible to avoid liability for installing or operating software simply by burying a disclosure of the existence of the software in the end-user license agreement (EULA)—the terms that a user must accept before most programs will install. It did not matter whether users read the disclosure or even whether they had a reasonable opportunity to read it.1 Nor would it have mattered how unreasonable the terms of the disclosure were.2 As long as the existence and operation of the program were accurately described, that would be sufficient.

More recently, however, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and courts have required that the disclosures be “conspicuous” and “material,” and that the EULA be capable of being printed or stored. Otherwise, the consumer’s “consent” is invalid. As a consequence, it is no longer possible to avoid liability merely through disclosure.

This chapter is concerned with the major legal provisions applicable to determining whether software that is installed or operates surreptitiously—that is, without the actual knowledge of the user—is legal. The chapter does not attempt to resolve whether a particular variety of surreptitious software is legal. It would be impossible to do so in the abstract, and any answer would likely be out-of-date before it was even published. Instead, this chapter tries to help the reader identify the important questions to ask about any program that installs or operates surreptitiously, and to highlight the legal significance of the answers. It is not intended to be legal advice, but rather to provide the reader with the information necessary to make informed decisions about when legal advice is necessary and whether the law applicable to surreptitious software needs to be supplemented or changed.

14.2 The Characteristics of Surreptitious Code

14.2.1 Surreptitious Download, Installation, or Operation

By definition, surreptitious code downloads, installs, and/or operates without actual user knowledge. This lack of knowledge may result from the user’s failure to read a clear disclosure, an inadequate or incomplete disclosure (e.g., failing to disclose that the software will generate pop-up ads), a false disclosure (e.g., promising that the software will remove adware when it actually installs it), a fraudulent disclosure (e.g., when a phishing message or pharming site fraudulently adopts the name and logo of a legitimate business), or the absence of any disclosure at all (e.g., “drive-by” downloads that do not provide the user with notice and take advantage of browser vulnerabilities so that the browser provides no warning of the download). Often surreptitious code is bundled without notice with files that users know they are accessing—music, jokes, sexual images, or other programs (“lureware.”) (See Chapter 3 for more details.)

14.2.2 Misrepresentation and Impersonation

Many types of surreptitious software not merely fail to disclose clearly their existence and operation, but actively deceive users about how they operate and what they do. Often this misrepresentation will involve impersonating a legitimate business or other organization through the use of its name, trademarks, and trade dress (e.g., the distinctive appearance of its web site or packaging). This is always true of phishing messages, phishing and pharming sites, and programs that generate messages and windows that appear to come from the operating system or browser. The Infostealer.Banker.D trojan, for example, is software that runs on the user’s machine and injects HTML content into the user’s web browser when the user visits sites such as paypal.com where sensitive information is shared. The user thinks the content is coming from PayPal, when in reality it is coming from the user’s own machine; whatever information the user enters is sent to a third party at a remote location.3

Questions surrounding what constitutes “surreptitious” and “deceptive” downloading, installation, or operation of software are among the most difficult and most important under current U.S. law. While in some situations the answers are clear (e.g., phishing or a false or fraudulent disclosure), in many others they are not. For example, what about the disclosure of material terms buried in the midst of a EULA, the failure to disclose in detail all of the operations of a given piece of software, or the fact that the software operates differently than the user anticipated? The law has not yet provided clear answers to these questions, and what answers there are may be changing as policymakers expand their expectations about the comprehensiveness, prominence, and accessibility of disclosures necessary to avoid the label “spyware.”

14.2.3 Collection and Transmission of Personal Data

Once present, surreptitious code often collects and transmits to third parties personal information about the computer user. The types of information and the uses to which it is put vary widely. For example, adware may monitor browsing habits to generate targeted advertising. Cookies often hold login and payment information so that the user does not have to reenter that same information in the future. Spyware, however, may collect those same data and transmit them to a third party to be used to commit financial fraud or identity theft.

14.2.4 Interference with Computer Operation

All software interferes to some extent with the operation of a computer by using the processor, occupying storage capacity, or requiring network bandwidth. With surreptitious software, the interference can be quite burdensome and occur in a wide variety of ways. For example, some software (e.g., backdoors) allows third parties literally to take control of a computer or even a network of infected computers (e.g., bot farms). Adware can generate pop-up ads that block the screen and require the user to divert his or her attention to closing the excess windows. Some programs can modify key system files, thereby destabilizing the computer. Dell reported in April 2004 that 25% of its service calls concerning spyware involved “significantly slowed computer performance.”4 Other surreptitious programs download files to the user’s hard drive; these files may then be used to distribute surreptitious code, sexually explicit or copyrighted material, or spam. Other types of surreptitious software interfere with the operation of browsers and search engines by directing users to sites competing with those for which they are searching.

14.2.5 Perseverance of Surreptitious Software

Many creators of surreptitious software make their programs difficult to remove. They may avoid the operating system’s Add/Remove Programs function or mask their software using operating system file names or by placing the software in directories usually reserved for operating system files. Rootkits are especially effective—and insidious—in using sophisticated techniques to hide their very existence (see Chapter 8 for more details). Some surreptitious software programs install thousands of files or make so many changes to the system registry that they are virtually impossible to detect and reverse completely. Another common technique is for surreptitious software to automatically reinstall itself when deleted.5

14.2.6 Other Burdens of Surreptitious Software

The effects of surreptitious software can extend far beyond interfering with the operation of individual computers. Many users report spending large amounts of time attempting to delete spyware or rebuilding systems that have been infected by them. Billions of dollars are spent each year on antivirus and anti-spyware software and updates. Microsoft reports that 50% of Windows XP operating system crashes are due to spyware.6 Dell and McAfee report that spyware accounts for 10% to 12% of all technical support calls.7 Surreptitious code can weaken computer security, interfere with online commerce, alter the behavior of web browsers and search engines, and compromise both individual privacy and the confidentiality of business information.

14.2.7 Exploitation of Intercepted Information

Information that is intercepted by surreptitious software can be exploited in a variety of ways that injure computer users—for example, to commit identity theft and perpetrate financial frauds. These activities are largely beyond the scope of this chapter. The use of another person’s credit card number or account name and password to commit fraud is illegal, irrespective of how the information is obtained. Nevertheless, the intended use of data obtained through surreptitious software may be relevant to determining the legality of that software, because liability often depends on the purpose for which the information was taken.

14.3 Primary Applicable Laws

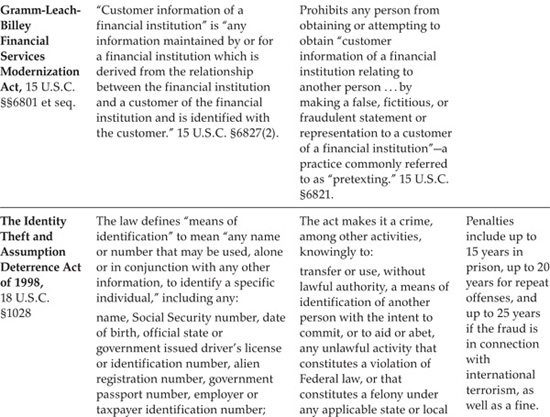

A variety of federal and state laws are applicable to many of the characteristic behaviors of surreptitious code described previously. As noted in the introduction to this chapter, it would be impossible to discuss them all. This section describes the four laws that are most applicable to surreptitious code and that have been most relied upon by litigants and courts in cases involving such software. Section 14.4 addresses a broader group of laws that apply to a narrower array of attributes of surreptitious code. All of the laws are summarized briefly in Table 14.1 beginning on page 442.

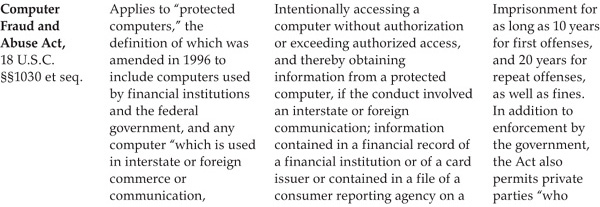

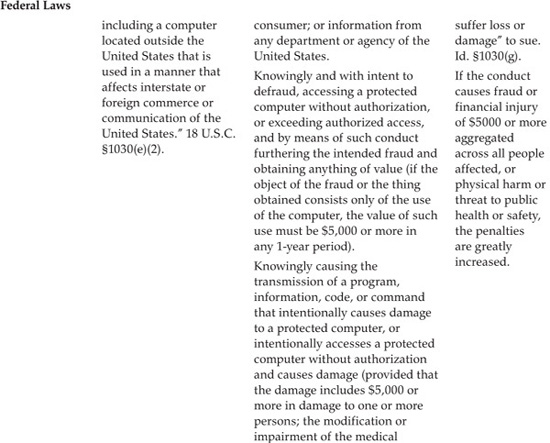

Table 14.1. Overview of laws relating to surreptitious code.

14.3.1 The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act

The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act is a federal law that creates a number of civil and criminal causes of action designed to prevent access to “protected computers” and exploitation of the information found there.8 The term “protected computer,” which originally limited application of the Act, was amended in 1996 to mean not only computers used by financial institutions and the federal government, but also any computer “which is used in interstate or foreign commerce or communication, including a computer located outside the United States that is used in a manner that affects interstate or foreign commerce or communication of the United States.”9 Given that almost any business computer or computer connected to the Internet would fit within this definition, the statute applies very broadly indeed.

The Act imposes liability on anyone who, among other things:

• Intentionally accesses a computer without authorization or exceeds authorized access, and thereby obtains information from a protected computer if the conduct involved an interstate or foreign communication; information contained in a financial record of a financial institution, or of a card issuer, or contained in a file of a consumer reporting agency on a consumer; or information from any department or agency of the United States.

• Knowingly and with intent to defraud, accesses a protected computer without authorization, or exceeds authorized access, and by means of such conduct furthers the intended fraud and obtains anything of value (if the object of the fraud or the thing obtained consists only of the use of the computer, the value of such use must be $5000 or more in any 1-year period).

• Knowingly causes the transmission of a program, information, code, or command that intentionally causes damage to a protected computer, or intentionally accesses a protected computer without authorization and causes damage (provided that the damage includes $5000 or more in damage to one or more persons; the modification or impairment of the medical examination, diagnosis, treatment, or care of one or more persons; physical injury; a threat to public health or safety; or any damage to a computer system used by the government in furtherance of the administration of justice, national defense, or national security).

• Intentionally and without authorization accesses any nonpublic computer of a department or agency of the United States.

• Knowingly and with intent to defraud traffics in any password or similar information through which a computer may be accessed without authorization, if such trafficking affects interstate or foreign commerce; or such computer is used by or for the government of the United States.10

The penalties for violating the Act include imprisonment for as long as 10 years for first offenses and 20 years for repeat offenses, as well as fines. In addition to enforcement by the government, the Act permits private parties “who suffer loss or damage” to sue.11

The Act clearly applies to many activities characteristic of surreptitious code—for example, intentionally accessing nonpublic government computers; intentionally collecting information from any financial institution, government, or other “protected computer”; or trafficking in login information. If the conduct causes fraud or financial injury of $5000 or more aggregated across all people affected, or if it causes physical harm or threat to public health or safety, the penalties are greatly increased.

The repeated use of the phrase “without authorization or exceeds authorized access” makes clear that the Act will apply if the user has not authorized the access, the access was authorized based on false or deceptive information, or the access exceeded that which was authorized.

14.3.2 The Federal Trade Commission Act

Section 5(a) of the Federal Trade Commission Act, the statute that created and empowers the Commission, prohibits unfair or deceptive acts or practices affecting interstate and foreign commerce.12 It is well settled that misrepresentations or omissions of material fact constitute deceptive acts or practices pursuant to section 5(a) of the FTC Act. For example, promising a customer that you will encrypt transactional data and then failing to do so is deceptive.

An act or practice is unfair if it causes or is likely to cause substantial injury to consumers that is not outweighed by countervailing benefits to consumers or to competition and that is not reasonably avoidable by consumers.13 Thus the failure to use reasonable security measures to protect a customer’s data, even in the absence of any promise to do so, is likely to be deemed “unfair.”

The actions commonly associated with surreptitious code qualify as deceptive acts or practices if they involve false, fraudulent, or misleading disclosures. They qualify as unfair acts or practices if they harm the user—for example, by inundating the user with pop-up ads or substantially slowing the user’s computer, especially if the software cannot be removed easily. Whether deceptive or unfair, the acts or practices will be subject to enforcement by the FTC as well as state attorneys general.

The FTC has made broad use of its section 5 authority in numerous cases involving spyware. For example, in the FTC’s recent case against Direct Revenue, and related companies, the FTC alleged that the respondent companies acted deceptively and unfairly.14 Deception was found in the fact that the respondent companies

represented to consumers, expressly or by implication, that they would receive software programs either at no cost, or at the advertised cost. Respondents failed to disclose, or failed to disclose adequately, that such software is bundled with respondents’ adware, which tracks and stores information regarding consumers’ Internet use and displays pop-up and other forms of advertisements on consumers’ computers based on such use. The installation of such adware would be material to consumers in their decision whether to install software offered by respondents or their affiliates or sub-affiliates. The failure to disclose or adequately disclose this fact, in light of the representations made, was, and is, a deceptive act or practice.15

The FTC alleged unfairness based on both the surreptitious installation and operation of the adware and the difficulty of removing or disabling the adware. With regard to the installation and operation of the software, the FTC alleged:

[R]espondents, through affiliates and sub-affiliates acting on behalf of and for the benefit of respondents, installed respondents’ adware on consumers’ computers entirely without notice or authorization. These practices caused consumers to receive unwanted pop-up and other advertisements and usurped their computers’ memory and other resources. Consumers could not reasonably avoid this injury because respondents, through their affiliates and sub-affiliates, installed the adware on consumers’ computers without their knowledge or authorization. Thus, respondents’ practices have caused, or are likely to cause, substantial injury to consumers that is not reasonably avoidable by consumers themselves and not outweighed by benefits to consumers or competition. These acts and practices were, and are, unfair.16

Regarding the impediments to uninstalling the software, the FTC charged that “respondents failed to provide consumers with a reasonable and effective means to identify, locate, and remove respondents’ adware from their computers.”17 In particular, the FTC noted the following practices:

• Failing to identify adequately the name or source of the adware in pop-up ads or other ads so as to enable consumers to locate the adware on their computers;

• Storing the adware files in locations on consumers’ hard drives that are rarely accessed by consumers, such as in the Windows operating systems folder that principally contains core systems software;

• Writing the adware code in a manner ensuring that it will not be listed in the Windows Add/Remove utility in conjunction with the software with which it was originally bundled at installation;

• Failing to list the adware in the Windows Add/Remove utility, which is a customary location for user-initiated uninstall of software programs;

• Where the adware was listed in the Windows Add/Remove utility, listing it under names resembling core systems software or applications;

• Contractually requiring that affiliates write their software code in a manner ensuring that it does not uninstall respondents’ adware when consumers uninstall the software with which it was bundled at installation;

• Installing technology on consumers’ computers to reinstall the adware where it has been uninstalled by consumers through the Windows Add/Remove utility or deleted by consumers’ anti-spyware or anti-adware programs; and/or

• [Providing] an uninstall tool [that] require[ed] consumers to follow a ten-step procedure, including downloading additional software and deactivating all third-party firewalls, thereby exposing consumers’ computers to security risks.18

As a result of these practices, the FTC asserted:

Consumers thus have had to spend substantial time and/or money to locate and remove this adware from their computers. Consumers also were forced to disable various security software to uninstall respondents’ adware, thereby exposing these computers to unnecessary security risks. Respondents’ failure to provide a reasonable means to locate and remove their adware has caused, or is likely to cause, substantial injury to consumers that is not reasonably avoidable by consumers themselves and not outweighed by benefits to consumers or competition. These acts and practices were, and are, unfair.19

The FTC stressed that there was deception and unfairness even though the existence of the adware was disclosed in the EULA that was accessible through one or more hyperlinks. It noted that the “inconspicuous hyperlinks were located in a corner of the home pages offering the lureware and or in a modal box provided by the computer’s operating system. Consumers were not required to click on any such hyperlink, or otherwise view the user agreement, in order to install the programs.”20

Direct Revenue settled the case with the FTC by signing a 20-year consent agreement promising not to engage in similar activity in the future, and paying $1.5 million in restitution.21

The FTC has applied both the deception and the unfairness prongs of the FTC Act to phishing as well.22 The analysis with regard to deception in phishing appears particularly applicable to deception in other surreptitious code contexts as well, because the FTC argued that it was deceptive for the defendant to claim, “directly or indirectly, expressly or by implication, that the email messages he, or persons acting on his behalf, send and the web pages he, or persons acting on his behalf, operate on the Internet are sent by, operated by, and/or authorized by the consumers’ Internet service provider or by the consumers’ online payment service provider.”23

14.3.3 Trespass to Chattels

The downloading, installation, and operation of surreptitious code may also constitute trespass to personal property—what the law usually calls “trespass to chattels.” Until its recent re-invigoration, trespass to chattels was a little-known tort (a civil cause of action for injury to one’s person, property, or legal interests) that fell between trespass (illegally occupying land) and theft (stealing personal, movable property). Historically, the tort required an intentional interference with the possession of personal property that caused an injury. Unlike theft, the tort does not require totally dispossessing the rightful owner; unlike trespass, some proof of harm or damage is required.

The trespass to chattels tort made its debut in the Internet context in 1997 in CompuServe, Inc. v. Cyber Promotions, Inc.24 There, the district court found that the millions of unsolicited commercial emails sent by Cyber Promotions to CompuServe subscribers, over the repeated objections of both the subscribers and CompuServe, placed a “tremendous burden” on CompuServe’s system, used “disk space[,] and drained the processing power” of its computers.25

From this fairly straightforward beginning, the tort has expanded in the Internet context into areas where both the interference with a possessory interest and the harm were less clear. For example in eBay, Inc. v. Bidder’s Edge, Inc., the defendant Bidder’s Edge operated a site that aggregated information from Internet auction sites.26 The user would enter the item he or she was looking for, and Bidder’s Edge would show on which, if any, major auction sites the item was available and at what current price. After an initially cooperative relationship with eBay crumbled, Bidder’s Edge adopted a strategy of using software robots to access eBay’s site as many as 100,000 times per day to collect information on ongoing auctions. The district court concluded that accessing eBay’s web site was actionable as a trespass to chattels not because it was unauthorized or because it imposed incremental cost on eBay, but rather on the basis that if Bidder’s Edge was allowed to continue unchecked “it would encourage other auctions aggregators to engage in similar recursive searching,” and that such searching could cause eBay to suffer “reduced system performance, system unavailability, or data losses.”27

This ruling marked the beginning of a series of cases testing the limits of trespass to chattels’ harm requirement. In Register.com, Inc. v. Verio, Inc., the district court appeared to eliminate the harm requirement entirely when it concluded that a “mere possessory interference”—interference with the possession or use of personal property without demonstrating any resulting injury—was sufficient.28

Typically, trespass to chattels claims have been brought by Internet service providers or web site or network owners. However, there is no logical reason why such a claim could not be maintained by the owner of a computer that had been “occupied” by a creator or distributor of surreptitious code, making the computer more difficult to use or less efficient. This is precisely the reasoning of those courts that have considered trespass to chattels claims in response to spam, as noted by the California Supreme Court:

A series of federal district court decisions, beginning with CompuServe, Inc. v. Cyber Promotions, Inc.... has approved the use of trespass to chattels as a theory of spammers’ liability to ISP’s, based upon evidence that the vast quantities of mail sent by spammers both overburdened the ISP’s own computers and made the entire computer system harder to use for recipients, the ISP’s customers. In those cases,...the underlying complaint was that the extraordinary quantity of UCE [unsolicited commercial email] impaired the computer system’s functioning.29

That would appear to be precisely the claim that victims of surreptitious code would advance: Their computers were occupied by software that diminished their performance or usability. In Sotelo v. DirectRevenue, LLC,30 a federal district court accepted precisely this claim. The fact that the plaintiff was an individual computer owner was deemed irrelevant: “The elements of trespass to personal property—interference and damage—do not hinge on the identity of the plaintiff, and the cause of action may be asserted by an individual computer user who alleges unauthorized electronic contact with his computer system that causes harm.”31 Moreover, other commentators have observed that “[t]he harm suffered to the plaintiff’s computer (use of memory and screen pixels), is similar to the harm the court recognized the plaintiff had suffered in CompuServe”[9].

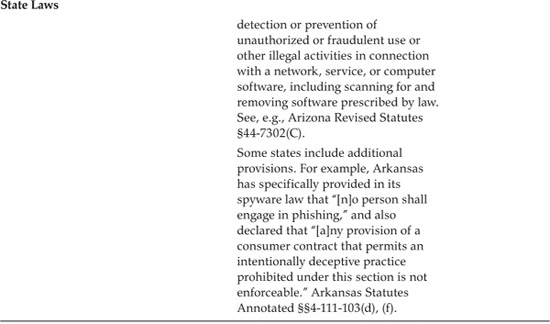

14.3.4 State Anti-Spyware Laws

Most states have laws like the FTC Act that protect against deceptive or unfair trade practices. Fourteen states, however, have gone further to enact laws specifically addressing surreptitious software. These laws apply both to activities that take place within each state and to activities directed toward the states’ residents, irrespective of where the perpetrator is located. These laws typically fall into one of three categories.

The largest category includes the laws promulgated by Arizona, Arkansas, California, Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Louisiana, New Hampshire, Texas, and Washington, all of which have adopted broad prohibitions against spyware.32 Although not identical, all of these laws follow the same model. They prohibit any person other than the owner or authorized user of a computer from knowingly transmitting or copying software to a computer and using that software to do any of the following:

• Modify, through intentionally deceptive means, settings that control the page that appears when the user launches an Internet browser, the default search engine, or the user’s list of web bookmarks. “Intentionally deceptive means” are defined as an intentionally and materially false or fraudulent statement; a statement or description that intentionally omits or misrepresents material information in order to deceive the user; or an intentional and material failure to provide notice to the user regarding the installation or execution of computer software in order to deceive the owner or operator.

• Collect, through intentionally deceptive means, personally identifiable information through the use of a keystroke logging function; in a manner that correlates the information with data respecting all or substantially all of the web sites visited by the user (other than web sites operated by the person collecting the information); or from the hard drive of the user’s computer. “Personally identifiable information” is defined as first name or first initial in combination with last name; home or other physical address including street name; email address; a credit or debit card number or bank account number or any related password or access code; Social Security number, tax identification number, driver license number, passport number or any other government issued identification number; or account balance, overdraft history, or payment history if they identify the user.

• Prevent, through intentionally deceptive means, a user’s reasonable efforts to block the installation or execution of computer software by causing that software automatically to reinstall or reactivate on the computer.

• Intentionally misrepresent that computer software will be uninstalled or disabled by a user’s action.

• Through intentionally deceptive means, remove, disable, or render inoperative security, anti-spyware or antivirus computer software.

• Take control of the computer by accessing a computer or using its modem or network connection to cause damage to the computer or cause the user to incur financial charges for a service that the user has not authorized, or opening multiple, sequential, stand-alone advertisements without the authorization of the user and that a reasonable user cannot close without turning off the computer or closing the Internet browser. “Damage” is defined as any significant impairment to the integrity or availability of data, computer software, system, or information.

• Modify a computer’s privacy or security settings for the purpose of stealing personally identifiable information about the user or causing damage to a computer.

• Prevent the user’s reasonable efforts to block the installation of, or to disable, computer software, by presenting the user with an option to decline installation with knowledge that the installation will proceed even if the option is selected, or by falsely representing that computer software has been disabled.33

In addition, under these broad state laws, it is unlawful for any person to

• Induce the user to install a computer software component on the computer by intentionally misrepresenting the extent to which installing the software is necessary for security or privacy reasons or in order to open, view, or play a particular type of content.

• Deceptively cause the execution on the computer of a software component with the intent of causing the user to use the component in a manner that violates any other provision of this section.34

There are broad exceptions for network and computer monitoring by a telecommunications carrier, cable operator, computer hardware or software provider, or provider of information service or interactive computer service. These exceptions apply if the purpose of the monitoring is for network or computer security, diagnostics, technical support, maintenance, repair, authorized updates of software or firmware, authorized remote system management, or detection or prevention of unauthorized or fraudulent use or other illegal activities in connection with a network, service, or computer software, including scanning for and removing software prescribed by law.35

Some states include additional provisions. For example, Arkansas has specifically provided in its spyware law that “[n]o person shall engage in phishing,” and also declared that “[a]ny provision of a consumer contract that permits an intentionally deceptive practice prohibited under this section is not enforceable,”36 thus eliminating consideration of whether the user agreed to a EULA that permitted the deceptive practice.

Depending on the state, damages for violating these statutes may include actual damages or statutory damages of up to $100,000 per violation, which in some states may be trebled if the defendant has engaged in a “pattern and practice” of violating these provisions (often defined as having engaged in the activity three or more times); court costs; attorneys’ fees; and injunctions. Some states also provide for criminal penalties.37 Civil lawsuits may be brought only by the state attorney general and the “computer software provider or a web site or trademark owner.”38 No state allows individual computer users to sue under its anti-spyware law.

The second category of state responses focuses exclusively on the use of surreptitious software to trigger pop-up ads based on search engine terms and URLs, or even to alter search results or actually divert browsers to benefit competing sites. Two states—Alaska and Utah—follow this approach.39 Their laws prohibit “deceptive acts or practices...using spyware,” but then define those very narrowly:

• Causing a pop-up advertisement to be shown on the computer screen of a user by means of a spyware program, knowing that the pop-up advertisement is triggered by a user accessing a specific trademark or web site, and the advertisement is purchased or acquired by someone other than the mark owner, a licensee, an authorized agent or user, or a person advertising the lawful sale, lease, or transfer of products bearing the mark through a secondary marketplace for the sale of goods or services.

• Purchasing advertising that violates the restriction on pop-up advertising if the purchaser of the advertising receives notice of the violation from the mark owner and fails to stop the violation.40

While this approach is noteworthy for its narrowness—it targets only one of the many types of damage that surreptitious code might cause—it does extend liability beyond the distributor of the code to include advertisers that pay for the code to be distributed.

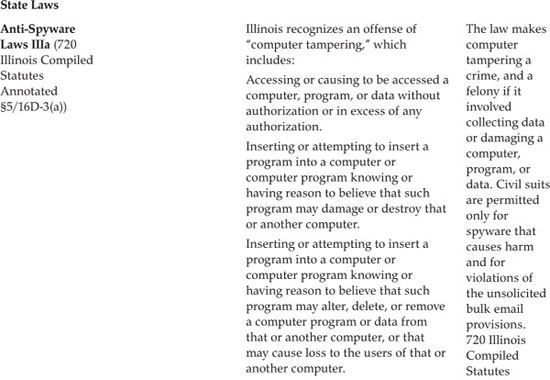

The third category of state responses includes a handful of more idiosyncratic approaches to surreptitious code. Illinois, for example, recognizes an offense of “computer tampering,” which includes the following activities:

• Accessing or causing to be accessed a computer, program, or data without authorization or in excess of any authorization.

• Inserting or attempting to insert a program into a computer or computer program knowing or having reason to believe that such program may damage or destroy that or another computer.

• Inserting or attempting to insert a program into a computer or computer program knowing or having reason to believe that such program may alter, delete or remove a computer program or data from that or another computer, or that may cause loss to the users of that or another computer.

• Falsifying or forging electronic mail transmission information or other routing information in any manner in connection with the transmission of unsolicited bulk electronic mail through or into the computer network of an electronic mail service provider or its subscribers.

• Knowingly to sell, give, or otherwise distribute, or possess with the intent to sell, give, or distribute, software which is primarily designed for the purpose of facilitating or enabling the falsification of electronic mail transmission information or other routing information; has only a limited commercially significant purpose or use other than to facilitate or enable the falsification of electronic mail transmission information or other routing information; or is marketed for use in facilitating or enabling the falsification of electronic mail transmission information or other routing information.41

The law makes computer tampering a crime, and defines the offense as a felony if it involved collecting data or damaging a computer, program, or data.42 Civil suits are permitted only for spyware that causes harm and for violations of the unsolicited bulk email provisions.43

Nevada has enacted some of the most sweeping restrictions on surreptitious code under the broad title, “Unlawful Acts Regarding Computers.”44 Under this law, anyone who “knowingly, willfully and without authorization” does any of the following commits a crime:

• Modifies, damages, destroys, discloses, uses, transfers, conceals, takes, retains possession of, copies, obtains or attempts to obtain access to, permits access to or causes to be accessed, or enters, data, a program or any supporting documents which exist inside or outside a computer, system, or network.

• Modifies, destroys, uses, takes, damages, transfers, conceals, copies, retains possession of, obtains or attempts to obtain access to, or permits access to or causes to be accessed equipment or supplies that are used or intended to be used in a computer, system, or network.

• Destroys, damages, takes, alters, transfers, discloses, conceals, copies, uses, retains possession of, obtains or attempts to obtain access to, or permits access to or causes to be accessed a computer, system, or network.

• Obtains and discloses, publishes, transfers, or uses a device used to access a computer, network, or data.

• Introduces, causes to be introduced or attempts to introduce a computer contaminant into a computer, system, or network. A “computer contaminant” is defined as any data, information, image, program, signal, or sound that is designed or has the capability to contaminate, corrupt, consume, damage, destroy, disrupt, modify, record, or transmit any other data, information, image, program, signal, or sound contained in a computer, system or network without the knowledge or consent of the owner.45

A separate Illinois statute makes it a crime to knowingly, willfully, and without authorization interfere with the authorized use of a computer, system, or network, or to knowingly, willfully, and without authorization use, access, or attempt to access a computer, system, network, telecommunications device, telecommunications service, or information service.46 Violation of these provisions is a misdemeanor criminal offense. If the violation was committed to defraud or illegally obtain property; caused loss, injury, or other damage in excess of $500; or caused an interruption or impairment of a public service (such as police or fire service), then it is a felony. In addition to the prison terms and fines normally used as penalties for a felony in Illinois, the court may impose an additional fine of up to $100,000 and is required to order the defendant to pay restitution.47

Many states, including California, Arkansas, and Texas, have adopted antiphishing statutes along with their laws addressing surreptitious code.48

14.4 Secondary Applicable Laws

14.4.1 The Electronic Communications Privacy Act

The Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 regulates the collection of information from electronic media and in other settings where there is an expectation of privacy.49 It is divided into three major parts, all of which could be relevant to surreptitious code. Although the Act applies to activities of both the government and the private sector, the discussion here focuses on its application to private-sector collection of data through spyware and other surreptitious software.

The first and oldest part—Title I, the Wiretap Act—was adopted in 1968 and deals with the interception of communications in transmission.50 The law prohibits the interception of the “contents of any wire, electronic, or oral communications through the use of any electronic, mechanical, or other device.”51 Spyware that collected data from a computer user and transmitted it to a third party might well violate this provision.

Several exceptions and definitional issues must be addressed. For example, any party to a communication may consent to the interception or disclosure of the communication, unless it is for the purpose of committing an illegal act.52 Thus, if the user agreed to the interception by accepting a EULA permitting it, the law would not be violated. (Many states have similar laws, but require the consent of all parties to a communication if the communication is to be recorded or intercepted.)

Similarly, most federal courts have found that there has been “interception” only when communications are acquired in transit and not from storage [35]. Moreover, two federal courts have held in cases involving keyloggers that only communications between the computer and an external network can be intercepted.53 Collecting keystrokes between keyboard and CPU alone will not qualify as an “interception,” so adware that does not communicate user data back to some other entity would not be affected by this law.

Finally, there is some ambiguity about the meaning of “content of a communication.” Historically, the U.S. Congress has carefully distinguished information about a communication (e.g., address or phone number) from the content of the communication. The statute defines “content” to include “any information concerning the substance, purport, or meaning of that communication.”54 The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit has found that this definition “encompasses personally identifiable information such as a party’s name, date of birth, and medical condition.”55 If surreptitious code causes the interception of communications contents as they enter and leave a user’s computer, Title I is clearly implicated. If the software captures only URLs and search terms, there is at least room for argument that this information does not constitute “content.”

Title II—the Stored Communications Act—was adopted in 1986 and deals with communications in electronic storage, such as email and voice mail.56 It provides for criminal penalties and civil damages against anyone who “(1) intentionally accesses without authorization a facility through which an electronic communication service is provided; or (2) intentionally exceeds an authorization to access that facility; and thereby obtains, alters, or prevents authorized access to a wire or electronic communication while it is in electronic storage in such system.”57

For Title II to apply, surreptitious code must gain unauthorized access to a “facility through which an electronic communications services is provided.”58 The term “facility” clearly includes telecommunications switches, mail servers, and even voicemail systems.59 To apply to most surreptitious code, the user’s hard drive would have to not only be a “facility,” but one “through which an electronic communication service is provided.” This issue remains unsettled, but at least one commentator has expressed skepticism that a hard drive would meet this definition.60

In addition, Title II applies only if the facility has been accessed without authorization or in excess of authorization, and, like Title I, contains an explicit exemption for consent.61 If the user accepted a EULA as a condition of downloading the program or accessing the site that contained the surreptitious code, it is possible that he or she may have consented to the code’s operation and that the access, even if it was to a facility, did not exceed authorization.

Title III—the Pen Register Act—was adopted in 1986 and significantly amended in 2001. It applies to “pen registers” (to record outgoing communications information) and “trap and trace” devices (to record incoming communications information).62 The information captured by these devices includes what is contained in a phone bill or revealed by caller ID, email header information (the “To,” “From,” “Re,” and “Date” lines in an email), and the IP address of a site visited on the web. Title III provides that “no person may install or use a pen register or a trap-and-trace device without first obtaining a court order.”63 As a practical matter, only state and federal government officials can apply for the necessary court order, so the law acts as a positive prohibition on private parties using these devices, unless an exception applies.

Title III contains a variety of exceptions for communications service providers that are not likely to be relevant here, but it also includes an exception for user consent. As a result, the same questions arise regarding what the user consented to in the EULA and whether that consent is valid.

In sum, the Electronic Communications Privacy Act has yet to be applied consistently to surreptitious code. There are many fact-specific inquiries, as well as some ambiguity yet to be resolved by courts. The most obvious and consistent theme throughout the Act is consent. Some efforts to use the Act in connection with surreptitious code—primarily dealing with cookies—have foundered on the existence of consent.64 But at least one lawsuit has survived the consent hurdle and, in the process, generated useful analysis of what consent requires.65 In In Re Pharmatrak, Inc. Privacy Litigation, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, drawing on prior cases, wrote:

“[A] reviewing court must inquire into the dimensions of the consent and then ascertain whether the interception exceeded those boundaries.” Consent may be explicit or implied, but it must be actual consent rather than constructive consent....

Consent “should not casually be inferred.” “Without actual notice, consent can only be implied when the surrounding circumstances convincingly show that the party knew about and consented to the interception.” “Knowledge of the capability of monitoring alone cannot be considered implied consent.” ...

Deficient notice will almost always defeat a claim of implied consent.66

This case and the authorities on which it relies suggest that for purposes of evaluating surreptitious code under electronic surveillance laws, in the absence of a clear disclosure of the data interception and transmission and evidence of consent more meaningful than merely installing a program, the consent exception will not apply. Specifically, it will certainly not apply where there is no notice or where consent is obtained through deception. This is consistent with the FTC’s application of its deception and unfairness powers and suggests that surreptitious code that does act to intercept communications from a computer user to a network or web site or other person will be governed by the Electronic Communications Privacy Act.

14.4.2 The CAN-SPAM Act

The Controlling the Assault of Non-Solicited Pornography and Marketing Act of 2003 imposes a number of requirements and limitations on senders of unsolicited commercial email. These constraints would severely restrict the distribution of surreptitious code by spam and the exploitation of users’ computers via surreptitious code to distribute spam. The Act creates six relevant criminal offenses:

• Accessing a computer connected to the Internet without authorization, and intentionally initiating the transmission of multiple commercial electronic mail messages from or through such computer;

• Using a computer connected to the Internet to relay or retransmit multiple commercial electronic mail messages, with the intent to deceive or mislead recipients, or any Internet access service, as to the origin of such messages;

• Materially falsifying header information (which includes “the source, destination and routing information attached to an electronic mail message, including the originating domain name and originating electronic mail address, and any other information that appears in the line identifying, or purporting to identify, a person initiating the message”) in multiple commercial electronic mail messages and intentionally initiating the transmission of such messages;

• Registering, using information that materially falsifies the identity of the actual registrant, five or more electronic mail accounts or online user accounts or two or more domain names, and intentionally initiating the transmission of multiple commercial electronic mail messages from any combination of such accounts or domain names;

• Falsely representing oneself to be the registrant or the legitimate successor in interest to the registrant of five or more Internet Protocol addresses, and intentionally initiating the transmission of multiple commercial electronic mail messages from such addresses; or

• Conspiring to do any of these things.67

In addition to these criminal provisions, the CAN-SPAM Act contains a number of other requirements applicable to commercial emailers that the distribution of surreptitious code via email is likely to violate. The Act

• Prohibits false and misleading header information;

• Prohibits deceptive subject headings;

• Requires that commercial email include a functioning return email address or other Internet-based opt-out system;

• Requires senders of commercial email to respect opt-out requests;

• Requires that commercial email contain a clear and conspicuous indication of the commercial nature of the message, notice of the opportunity to opt out, and a valid postal address for the sender; and

• Prohibits the transmission of commercial email using email addresses obtained through automated harvesting or dictionary attacks.68

Penalties for violating the criminal provisions include imprisonment for up to five years and a fine. Violation of the civil provisions may be punished by assessment of actual damages and statutory damages of as much as $2 million, which may be trebled if the defendant acted willfully or knowingly.

14.4.3 Intellectual Property Laws

Under the federal Trademark Act of 1946, called the Lanham Act, a trademark protects a word, phrase, symbol, or design used with a product or service in the marketplace.69 A trademark may be thought of as a “brand.” Most company and product names and logos, as well as many domain names, are trademarks. Trademarks that are registered with the U.S. Trademark Office are usually accompanied by an ®. But trademarks do not have to be registered to be protected, and unregistered trademarks are often indicated with a TM (or SM, which indicates an unregistered mark in connection with a service). Trademark rights may continue indefinitely, as long as the mark is not abandoned by the trademark owner or rendered generic by having lost its significance in the market.

Anyone who uses a trademark in a way that confuses or deceives the audience as to the source of the product or service, or that dilutes the uniqueness of the mark, may be liable under federal law. For example, the Lanham Act provides for causes of action for misappropriation of a trademark, “passing off” the goods of services of one entity for those of another, and false advertising.

Surreptitious code may run afoul of federal trademark laws in a number of ways, but three means appear most immediately relevant. First, if the code is distributed in deceptive ways that falsely employ the name, logo, slogan, domain name, or trade dress of a legitimate business, a trademark claim may arise. Second, if the code operates to generate specific search results or direct the browser to specific web sites when the user searches for a trademarked name, a trademark claim may arise. (Recall that this activity is also regulated by state laws adopted in Alaska and Utah.) Finally, if the surreptitious code involves phishing or pharming, which by definition involve the impersonation of a legitimate business, a trademark claim may arise.

Most states have unfair competition and false designation or origin statutes or common law provisions that mirror the Lanham Act.

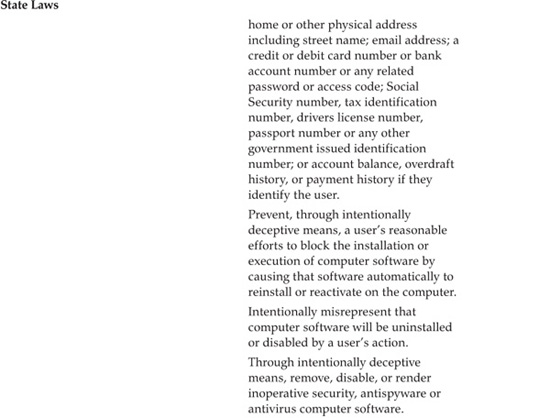

14.4.4 Identity Theft and Fraud Laws

The Identity Theft and Assumption Deterrence Act of 1998, as the title suggests, largely targets identity theft per se, but it is written sufficiently broadly that it also applies to the acts of obtaining and using information through surreptitious software.70 The act makes it a crime, among other activities, knowingly to

• Transfer or use, without lawful authority, a means of identification of another person with the intent to commit, or to aid or abet, any unlawful activity that constitutes a violation of Federal law, or that constitutes a felony under any applicable state or local law; or

• Traffic in false authentication features for use in false identification documents, document-making implements, or means of identification.71

The law defines “means of identification” to mean “any name or number that may be used, alone or in conjunction with any other information, to identify a specific individual,” including any

• Name, Social Security number, date of birth, official state or government issued driver’s license or identification number, alien registration number, government passport number, employer or taxpayer identification number;

• Unique biometric data, such as fingerprint, voice print, retina or iris image, or other unique physical representation;

• Unique electronic identification number, address, or routing code; or

• Telecommunication identifying information (telephone number) or access device (account number or password).72

“Traffic” is defined to mean “to transport, transfer, or otherwise dispose of, to another, as consideration for anything of value; or to make or obtain control of with intent to so transport, transfer, or otherwise dispose of.”73

Prior to passage of this act, most laws did not treat the individual whose identity was being impersonated as a “victim.” The retailer, bank, or insurance company that had been defrauded was considered a victim, but, unless the individual whose identity had been taken had also been defrauded, the law did not recognize that he or she had been injured. As a consequence, the individual had no standing before a government agency or court.

The act changed all of that by making identity theft itself a separate offense. As a result of these very broad provisions, obtaining, storing, transferring, or using a name, Social Security number, date of birth, account number, password, or other means of identification or account access with the intent to commit or assist any felony is a separate criminal offense under this statute. Penalties include up to 15 years in prison, up to 20 years for repeat offenses, and up to 25 years if the fraud is in connection with international terrorism, as well as a fine.74

The Act also assigned responsibility for violations to a variety of federal agencies, including the U.S. Secret Service, the Social Security Administration, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the U.S. Postal Inspection Service. Such crimes are now prosecuted by the U.S. Department of Justice. This law also allows for restitution for victims.

All but two states—Colorado and Vermont—have also criminalized identity theft as a separate offense, distinct from any other crime committed by the identity thief.

The Credit Card (or “Access Device”) Fraud Act was designed to deal with the production and use of fraudulent credit cards, card-processing equipment, and other “access devices.”75 It might, therefore, appear to have little application to surreptitious software. However, the statute’s terms are so broad as to apply to some types of such software. For example, the act defines “access device” to include

any card, plate, code, account number, electronic serial number, mobile identification number, personal identification number, or other telecommunications service, equipment, or instrument identifier, or other means of account access that can be used, alone or in conjunction with another access device, to obtain money, goods, services, or any other thing of value, or that can be used to initiate a transfer of funds (other than a transfer originated solely by paper instrument).76

The act makes it a criminal offense to “knowingly and with intent to defraud” (among other things)

• Produce, use, or traffic in one or more counterfeit access devices;

• Traffic in or use one or more unauthorized access devices during any one-year period, and by such conduct obtain anything of value aggregating $1000 or more during that period;

• Possess fifteen or more devices which are counterfeit or unauthorized access devices;

• Produce, traffic in, have control or custody of, or possess device-making equipment;

• Effect transactions, with 1 or more access devices issued to another person or persons, to receive payment or any other thing of value during any 1-year period the aggregate value of which is equal to or greater than $1000;...

• Without the authorization of the credit card system member or its agent, cause or arrange for another person to present to the member or its agent, for payment, 1 or more evidences or records of transactions made by an access device.77

The act provides for stiff penalties—up to 15 years in prison and up to 20 for repeat offenses under this law, as well as a fine.78

Surreptitious software can also violate the Federal Wire Fraud Statute, which creates a criminal offense applicable to:

Whoever, having devised or intending to devise any scheme or artifice to defraud, or for obtaining money or property by means of false or fraudulent pretenses, representations, or promises, transmits or causes to be transmitted by means of wire, radio, or television communication in interstate or foreign commerce, any writings, signs, signals, pictures, or sounds for the purpose of executing such scheme or artifice.79

Violators are subject to 20 years in prison, or 30 years if a financial institution is affected, as well as a fine.80

As with all of the criminal provisions discussed in this chapter, the federal wire fraud statute applies to conduct that affects interstate commerce and U.S. commerce with other nations. U.S. courts tend to interpret these terms broadly to apply U.S. law to situations in which either the perpetrator or the victim of the fraud is located within U.S. territory, and even to situations where neither is located in U.S. territory as long as the conduct affects U.S. commerce.

14.4.5 Pretexting Laws

Section 521 of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Financial Services Modernization Act, which took effect in 1999, prohibits any person from obtaining or attempting to obtain “customer information of a financial institution relating to another person...by making a false, fictitious, or fraudulent statement or representation to a customer of a financial institution”—a practice commonly referred to as “pretexting.”81 Section 527(2) defines customer information of a financial institution as “any information maintained by or for a financial institution which is derived from the relationship between the financial institution and a customer of the financial institution and is identified with the customer.”82

As a result, it is logical to conclude, and the FTC has argued in the context of phishing, that fraudulently obtaining financial account, credit card, or other information necessary to access a financial institution account, even though the information is obtained from the customer rather than the institution, is a violation of this provision.83 This would be true even if the information were never used to access the account or to otherwise steal money from the individual or the institution.

If true with regard to phishing, the same argument would seem to have equal force where surreptitious code is downloaded or installed subject to a “false, fictitious, or fraudulent statement or representation” and operates to obtain “customer information,” including account, credit card, or other information necessary to access a financial institution account.

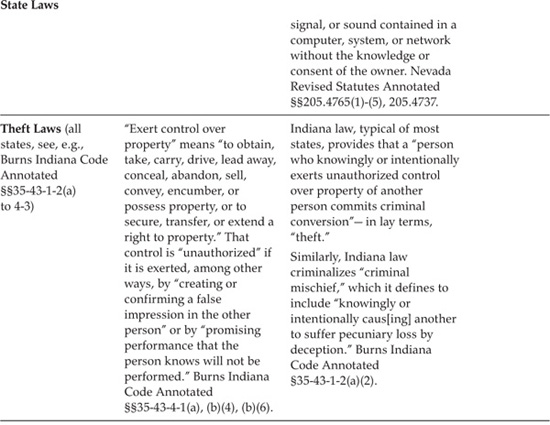

14.4.6 State Theft Laws

Obtaining, or attempting to obtain, valuable information under false pretenses would likely violate criminal conversion laws in every state. For example, Indiana law—like the laws of most states—provides that a “person who knowingly or intentionally exerts unauthorized control over property of another person commits criminal conversion”; in lay terms, the person commits “theft.”84

The law defines “to exert control over property” broadly to mean “to obtain, take, carry, drive, lead away, conceal, abandon, sell, convey, encumber, or possess property, or to secure, transfer, or extend a right to property.” That control is “unauthorized” if it is exerted, among other ways, by “creating or confirming a false impression in the other person” or by “promising performance that the person knows will not be performed.”85

Similarly, Indiana law criminalizes “criminal mischief,” which it defines to include “knowingly or intentionally caus[ing] another to suffer pecuniary loss by deception.”86 This aptly describes the behavior of much surreptitious code.

Conclusion

It is plain even from this brief survey that there is no shortage of laws applicable to surreptitious code and that those laws reach most, if not all, attributes of how such code is downloaded, installed, and used. At the FTC’s 2005 Spyware Workshop, both the FTC staff and the Department of Justice officials who participated stressed that their current statutory authority was sufficient to prosecute spyware distributors.87 Since then, 13 additional states have adopted relevant legislation. The FTC has brought numerous cases under its section 5 authority to prosecute deceptive or unfair acts and practices, as have states’ attorneys general under state laws. In January 2007, the New York Attorney General demonstrated just how far the law reaches by settling a major case against Priceline, Travelocity, and Cingular for promoting their products and services through adware, even though the adware was placed by third parties.88

In addition to the Federal Trade Commission Act and state consumer protection laws, the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, the common-law trespass to chattels doctrine, and state anti-spyware laws have been used to target surreptitious code. Many other laws may eventually be brought to bear in this area. To be sure, there are inherent difficulties associated with investigating and prosecuting cases involving surreptitious code, owing to the challenges associated with its global perpetrators, fast-changing tactics, and surreptitious nature.89 And law is only one—and perhaps the least important one—of many tools for dealing with surreptitious code. Technologies and consumer education are equally, if not more, important. Even so, there is plenty of relevant law, its reach is very broad, penalties can be staggering, and enforcement does work.

In fact, the major issue about law may be not whether there are enough laws, but rather whether there are too many laws or too much ambiguity in existing laws. Because of the breadth of many of the applicable laws, even software features that are intended to be innocent or beneficial may run the risk of creating liability. For example, adware to improve the relevance of advertisements to users, cookies that enhance consumer convenience and recognition when visiting familiar web sites, and monitoring software that allows parents to track their children’s computer use or facilitate remote diagnostic testing of computers all run the risk of violating the law if not deployed with clear, conspicuous notice and consent. Because of the variety and complexity of applicable laws, determining precisely what is and what is not permitted is rarely easy or certain, but it is essential to diminish the risk of liability.