CHAPTER 1

Introduction to Cross-Cultural Management

Contextualizing Background Information

Globalization has probably developed faster than our capacity to “digest” all the changes it involves. One of the most stunning revelations that accompany globalization is the notion that geographical distance has changed, and with it, the way business is done.

Although globalization was estimated to have only limited effects, this is simply not the case any longer. Businesses that aim to remain mononational would simply lose too many competitive advantages to survive in any market. This obvious reality, no matter how hard to swallow for some, has been dealt with by technology quite efficiently. But the main aspects that could determine whether a business of any size would survive or die are relationships and communication: technology being an asset that is available to all players at the same level, the main competitive success factors remain (1) innovation and (2) the capacity to develop, entertain, and maintain business across borders.

Those who manage to gain the latter will probably win over those who do not, and to profit from that extra mile, the understanding of other cultures and their dynamics becomes crucial.

Many authors have tried to define what culture is and how it develops. The most commonly used definitions have originated in varied social sciences including psychology, sociology, and anthropology.

Some of these definitions include Sigmund Freud’s “Culture is a construction that hides the pulsional and libido-oriented reality,” Herder’s “Every nation has a particular way of being and that is their culture,” Kardurer’s “Culture is the psycho characteristic configuration of the basis of the personality,” and Sapir’s “Culture is a system of behaviours that result from the socialisation process.” Most of these definitions have in common the relationship between the individual and the society (s)he belongs to, and point to the “cultural” factor as being the key element of the dynamics that enhances the rapport between the two.

The notion of culture had not been thoroughly explored (or at least the concept had been not thoroughly disseminated) in management science until the 1970s. It was only in the 1980s that Dutch researcher Geert Hofstede wrote about business anthropology for the first time in his book Culture’s Consequences,1 which opened the door to a new discipline that studied the impact of cultural diversity on business.

Since Geert Hofstede’s initial work, much has taken place in terms of updating of his data and applying it to the study of cross-cultural management. The most famous one is probably the Global Learning and Observations to Benefit the Environment (GLOBE) study, which included research on 62 societies and their approaches to leadership.2 Similar updates have been published, but not many have included a significant number of countries.

Hofstede’s definition of culture, which is certainly the most widely considered by both academics and practitioners in the management arena, states that:

Culture is the mental programming of the human spirit that allows distinguishing the members of one category in comparison with the members of another category. It is the conditioning that we share with the other members of the same group.

The key word in Hofstede’s definition of culture is certainly “mental programming.” It appears as both the link that “glues” all members of a group through a common set of assumptions and the behaviors resulting from them. At the same time, this collective similarity defines members by the exclusion of those who do not share the same background, and signs and symbols are therefore designed to exteriorize and, if possible, make visible who is part of which category and who is not.

Mental programming is a learnt attitude to life and a set of expected behaviors that could easily lead to stereotyping, as a safety net produced by society, to avoid the expected delusion that could naturally lead to frustration in having to face reactions that do not match with what is supposed to be “the natural way of acting and feeling” according to what the reference group has taught its members since their early childhood.

The Notion of Mental Programming

Geert Hofstede, who as mentioned above could be considered the father of business anthropology, has developed the concept of “mental programming.” Mental programming is what makes us expect a certain type of behavior from others. Any other action or reaction will be interpreted in varied ways, from “weird” to “shocking.” Interpretations of the same behavior may differ and vary from culture to culture.

For example, if I am from a culture where the boss has to show authority at all times and his/her decisions are not to be contested or even questioned by subordinates, then my mental programming will make me surprised when confronted with a situation in which a trainee openly objects to a comment made by the Director General in a meeting in front of all the other employees. Perhaps, in a different culture the same behavior would be interpreted as extreme interest, enthusiasm, and willingness to contribute, as expressed by the trainee.

Mental programming has to do with the glass through which we see life. We understand other people’s behavior (or we fail to understand it) according to the perspective from which we explore their attitudes and actions, and these viewpoints are strongly hardwired in the notions we have incepted through the socialization process.

In social sciences’ jargon, the word “socialization” refers to the process through which one learns the basic notions of “good,” “bad,” “acceptable,” “non-acceptable,” “okay,” and “not okay.” Social learning (or socialization) does not occur in a formal manner, but in an informal way, through experience and trial and error. When a mother suggests to her female children that they ought to learn how to do the cleaning and the washing at home, whereas their brothers are dispensed from that task, little girls learn that they are expected to assume a social role later on in life that is more connected to the care and service of their families, rather than with what is considered as “male activities” (the activities the boys of their age are expected to perform).

We are socialized by what our parents tell us, also by how they talk to us, how they react to others, and in particular by how they react to us, according to whether they consider our own behavior to be acceptable or not. Showing emotions in public, for example, can be considered as acceptable and even desirable in Southern European cultures, as it is commonly considered that those who are “poker faced” are not to be trusted. On the other hand, in Scandinavian cultures, not being able to control your emotions is perceived to be a sign of immaturity and related behaviors can be punished by a generalized shunning of the person exposing them.

However, parents are by far not the only socialization factor. Equally important are school, TV programs, and the media, which teach us what is correct or incorrect, normal or abnormal, acceptable or unacceptable. For instance, since the mid-2000s, European TV has made efforts to show representatives of minorities. Suddenly, weather presenters were not exclusively White and Asian, Latino, and Black Bond girls invaded the cinema screens in an attempt to generate a larger inclusion of previously neglected minority groups, who had been subconsciously receiving the message that “only white people are nice and showable on TV” and “Bond girls are usually blond”, and therefore may have understood “I can never be fully included in this society, which is basically not designed for people like me.”

Socialization can therefore be defined as a means to learn how to behave in a particular society, and is a basic element of our mental programming, which is the link that defines our belonging to a culture by the exclusion of those who do not share it.

The Facebook trail below illustrates a real-life case of cultural misunderstanding experienced by a British traveler (Stephen Gabbutt), on a business trip to Italy with his family, and the reactions of some of his compatriots (a few, a bit fueled by the author of this book).

Stephen Gabbutt |

None of the horde of Italian kids on today’s BA flight have sat in the right seats, so none of the Brit families and couples can sit together, classic Italianess. Can we go now? |

Veronica Velo |

Get culturally sensitive by kicking those kids’ arses. Latin parents (whether they are Latin American or Latin European) tend to outsource to strangers the setting of limits to their children because they fear the loss of their love. Too much Francoise Dolto in their readings, see?... Actually, my cousins’ children usually refer to me as “the ugly witch who lives by a scary Castle in Europe”. |

July 25 at 1:02 pm · LikeUnlike · 1 person Ged Casey likes this. |

|

Candice Hart |

Give the ex lax and pretend it’s chocolate and when they pooping their pants outside the toilet you can steal their seats. |

July 25 at 1:36 pm · UnlikeLike · 1 person Loading... |

|

Alison Clark |

Its probably BAs fantastic seat allocation system. We were on a flight to Paris once and had to sit behind each other, as did another couple near us. Hope you found a quiet corner! |

July 25 at 2:01 pm · LikeUnlike |

|

Stephen Gabbutt |

Thanks for the comments Ladies, just seeing a load of pooped British BA customers trying to explain to 11 year old Italians that they where sitting in their seat using hand gestures and pointing at their tickets was priceless. I’m sorry to say Lady V I don’t do culturally sensitive and it just makes me shout loader and point more. |

July 25 at 5:50 pm · LikeUnlike |

|

|

Veronica Velo |

I am about to start up a birth control campaign just to piss the Pope off. Will you travel to Rome with me in order to distribute free condoms? It sounds like a long term solution... |

July 25 at 6:00 pm · LikeUnlike |

|

|

Veronica Velo |

Why did you not ask the BA onboard crew for assistance? They should have replaced all the children in the right seats, shouldn’t they? |

July 26 at 10:29 pm · LikeUnlike |

|

|

Stephen Gabbutt |

They tried, but many of the single travelling business blokes just sat somewhere else to save the time. |

Wednesday at 8:02 am · LikeUnlike |

In the above dialog, we can distinguish some of the elements that constitute the stereotypical British mental programming, as opposed to the Italian one.

In Italy, the general assumption is that rules can be slightly (at least) broken. Rules are imperfect, and they are not universal. They need, therefore, to be adapted to each situation. Rules such as seating arrangements may be seen as a formality that can be disregarded if other options are available that cause no discomfort to anyone (as rules do not necessarily derive from rationality, but perhaps from the need of the President of the Airline to reinforce his power through the imposition of aleatory norms). In this case, the fact of having children sit anywhere was not perceived as a disruption, but as a slight alteration to the rules that would make the children as happy as their parents (who would manage to get rid of them for a while). This behavior may have bothered the British passengers, but as ties with them were not expected to last for longer than 2 hours, there was not much point in trying to please them.

On the other hand, relationships between Italian parents and their children are meant to last for life. Children in Italy have traditionally been considered as those who will take care of their parents in their old age (perhaps as a payback to their parents, for having taken care of them when they were young), and therefore are spoiled much more than British children. Italian children, have traditionally played the Social Security role for parents in their old age, and therefore the emotional links between them have developed in different ways than in the United Kingdom.

In the British mindset, on the other hand, rules are supposed to be the result of thorough thought on what would be the best way to ensure the common good (in this case, a pleasant flight for everyone). And as long as rules are clearly communicated, it is everyone’s duty to abide by them. Failure to do so can be considered as a sign of rudeness or disrespect toward those who have to suffer from the consequences of such actions. Also, children are expected to behave, and it is their parents’ duty to make sure that they learn not to disturb others. The behavior of children is supposed to be the responsibility of their parents.

In such a context, the sources of conflict are multiple, as are the reactions from each party, directly deriving from their different mental programming, which is interestingly incompatible.

For instance, the Italians would have expected the British adults to talk to the children directly and have them move from the seats they were occupying without caring much about whether the children would find other seats or not (they probably would not have, as the single businessmen were occupying them at the time). By doing so, the conflict would have been smaller (there is usually no conflict because the Italian children would probably have moved when told to do so by an adult) and then the Italian parents would have assumed the charge of making arrangements with the businessmen.

It is worthwhile noticing that the notion of time and its use is very different across cultures. A British person would have considered a delay in the flight as something much more serious than an Italian (who would probably have considered it as part of the fun of traveling), and therefore the Italian parents would not have taken into consideration the extra time involved in rearranging the seating once, and if, the British had complained.

The reaction of the British was also quite strange to the Italians. Why would they just present the problem after a solution had been found?

The Italian parents must have felt quite surprised that the British parents confronted them at the arrival airport. If they were so angry about the change in seating, why had they not said so before? And actually, why were they so angry, instead of being grateful for having been given the glorious chance of relaxing out of the way of the misbehavior of their children for a while? For the Italians, the fact that the British did not complain before or during the flight meant that the slight change in rules did not actually bother them so much. For the British, it meant that there was no point in delaying a flight for a quarrel, but that the point had to be made regarding the situation in order to re-establish a sense of justice.

It is also interesting to note the comments of the British Facebook friends. Some tried to be polite and funny about the situation, suggesting a revenge for the “affront” at least equivalent in strength: “the poisoning of the children” (this was obviously a joke, but the interesting part is that there was the assumption that the Italians had meant to bother them and therefore ought to be punished for that). In a culture in which conflict and expression of emotions are to be minimized in order to ensure harmony and the continuing of social processes with minimum disruption, a quiet payback allowing to “set the accounts right” appears to be the most civilized option. Interestingly enough, for the Italians, having a British adult telling their children off would not have shocked anyone and would have appeared as a simple act of civilization for which they might even have been grateful, as it would have contributed to the general education of their little ones. On the other hand, any sort of quiet revenge would have led them to think of the British as “those poker-faced people who stab you in the back” (to remain within the same tone of funny exaggeration).

Other British comments blamed the procedures, probably because according to those making the comments, a good system cannot fail. Failure occurs out of the system, not out of people in it. In other words, if the Italians did not end up in the assigned seats, it must have been because the seating arrangement was wrong. In no (British) mind would it be normal to think that any civilized individual would simply ignore British Airways policy. Besides, such a statement was an attempt to show the open-mindedness of the poster, as the assumption was that it was all part of a professional mistake, nothing to do with Italian “lack of consideration.” The Facebook friend in this case just failed to ignore that what could be considered as an act of disrespect in a British mindset would not be so in an Italian one, and vice-versa, as in an Italian mind making a fuss about a seat during a relatively short flight was just a sign of excessive rigidity and lack of flexibility, which showed no attempt to develop peaceful relations with passengers from another country (the height of impoliteness and lack of civility in an Italian mind).

Interestingly enough, the “victim” in this anecdote gave up. He was frustrated, but surrendered to the fact that there would have been no way to communicate with the other party. He just gave up, obviously due to the language barrier to start with, but also knowing that the misunderstanding would be rooted deeper than that. His unwillingness to make an effort was probably partly based on his exasperation when thinking that it would be up to him to go against his own mental programming by “acting Italian” (i.e., doing what no British person would do, like telling a stranger’s child off) or educating the Italians on his own mental programming (i.e., in Britain, telling someone else’s child off is worse than telling the parents off, not only because it can be considered abuse, but also because it suggests the parents are unable to assume their social role as educators).

My own first reaction to the scenes presented was to suggest that Italians should stop existing, as their very existence in the world would bother the British (always pushing on the very British joking style of communication), to which there was no immediate response. Anything expressed in that sense could have been considered rude, impolite, or—even worse—racist, and that would be definitely not British at all.

So, if you were British and you were in a similar situation, what would you have done? Below is my humble suggestion.

|

Veronica Velo |

If I were you, I would write a complaint letter to BA because it is part of their job to make sure that logistics run smoothly. Also, remember that and part of what you paid over what you would have paid to travel with Ryanair or other cheap airlines was supposed to be justified by the fact you could sit next to your family. So they owed that to you as a company. By the way, if you could include my business card in your letter and suggest BA buys some of my training on how to avoid this sort of problems in the future, I would be grateful... (and you would get a commission, of course!) |

Wednesday at 10:18 am · LikeUnlike |

|

Veronica Velo |

I am using this trail in my book. You are not allowed to sue me for plagiarism and you will touch no royalties, though. |

a few seconds ago · LikeUnlike |

Challenging one’s own mental programming requires much energy. It demands almost more energy than learning a new language, because it implies assuming that everything one knows for sure may be wrong in another context, and this can be destabilizing.

How insecure can one feel if suddenly everything that was an absolute truth became ambiguous or uncertain, or even easily challenged by others who have a different absolute truth they stand by?

Many have chosen to bomb those with different ideas, to eradicate them from the surface of the Earth, and others have even concocted plans to make them disappear or simply kick them out of their countries. For those following these ideas, this book and the understanding of the concept of culture is of no use.

On the other hand, if the aim is to do business with people who come to the negotiating table or to work as a team with those who have a different mindset, then the challenge is on, and knowing as much as possible about their feelings and thoughts (basically where they are coming from) can help simply because the understanding of mental programming is all that it is about.

An old Chinese parable recounts the tale of a few blind men trying to describe what an elephant is. As they cannot see, each one of them is touching a different part of the animal and making attempts to describe what it is like based on their tactile impressions. The one touching the eye says, “an elephant is a round, wet surface,” to which the one holding the tail responds “not at all, an elephant is like a rope,” and the third one, touching the leg, says, “an elephant is like a vertical tube, with a nail at the bottom.” Obviously all men are right, but their truth is only partial. It is only through dialog and willingness to talk to each other that they can reach a “universal” truth, if ever. When facing similar situations, the question is whether it is best to challenge one’s mental programming (accept that what seems obvious to us may only be relatively true and accept other points of view, no matter how annoying, inconvenient, or ridiculous these could be) or simply reject these and remain stuck to one’s convictions based on social standards.

Mental programming, no matter how constraining, is nevertheless not useless. It allows us to “get a grip” of what the world could be like at first sight and it helps us understand at least part of the reality that surrounds us, and this is crucial for us as social beings. When going international, although facing other mental programming and encountering other sets of assumptions becomes inevitable, a more complex viewpoint is required, an international one; that of a person who is ready to admit that s(he) may be considering the elephant from a relative perspective, not just out of politeness, but out of conviction.

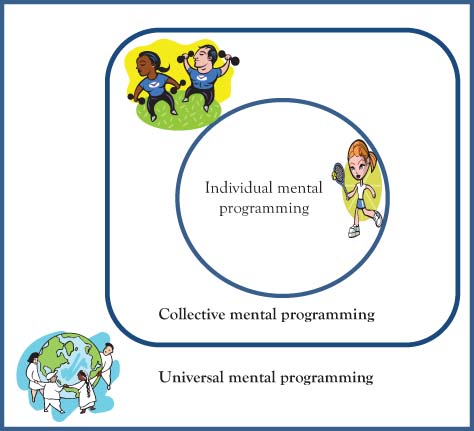

Mental programming exists at three levels: individual, collective, and universal (Figure 1.1).3 Individual mental programming includes all the preconceptions and structures that each one of us has developed as a result of our own personal experiences and exposure to different environments. Collective mental programming is shared by a particular group, which perceives reality in their own specific way. Universal mental programming contains all structures of thought that are shared by humans.

- An example of individual mental programming: I only buy and use handbags with many divisions because they allow me to keep my belongings in order and to easily access my diary while I am talking over the mobile phone.

- An example of collective mental programming: Women from certain cultures may expect men to pay for the bill at the restaurant, as it could be considered courteous for women to pay only when there are no men at the table.

- An example of universal mental programming: eating regularly.

When dealing with counterparts from different countries at a superficial level, we might reduce our interactions to levels that hardly exceed the level of universal mental programming, or perhaps just touch collective mental programming relating to specific generic groups that all the people concerned belong to anyway (a professional group following routine rules, a diplomatic team acting under the same protocol, etc.). These interactions can take place at a formal or informal level, but the knowledge of the parties concerned and the sharing of their lives remains vague and superficial.

Conflict or culture shock will appear when collective mental programmings interact and assumptions are not the same, leading to unfulfilled expectations and behavior considered as weird. At a personal level, mental programming becomes individual, and therefore the surprises to be processed are the same, whichever culture or social group the individuals concerned may belong to.

Values

The main component of mental programming is values. Values are a tendency to prefer one situation to another. A person believes in a value if he or she firmly thinks that a way of behaving is better than all others, and this, for either personal or social reasons. Values are key components of individual, collective, and universal mental programming.

The following example illustrates how values affect mental programming and how a “clash” of mental programmings can affect business relations. Khalid M. Al-Aiban and J. L. Pearce conducted a study called “The influence of values on management practices,”4 in which they demonstrated that:

- Managers in Saudi Arabia allocate rights and responsibilities to citizens who represent their families according to both the family’s social rank and their personal status in society. Positions are then obtained through a mix of both individual merit and family position.

- Managers in the United States allocate rights, responsibilities, and give promotions to employees mainly according to their merit.

- Differences between the national samples have revealed them to be cultural. It is not that Saudi Arabian managers are unable to understand managerial practices that are commonly applied in the United States. These managers do not apply them because they are incompatible with their values.

Our values affect almost every decision we make. Dealing with people who hold different values can be irritating and exhausting, but in most cases competitive advantage is gained by those who manage to understand the dynamics of intervalue deal making over those who decide to give up. Markets can be gained, opportunities tackled, and profitable partnerships sealed, if certain openness is shown toward the fact that values can differ cross-culturally.

Values are emotional by definition, and the fact that they are not rooted in rationality may contribute to the frustration of doing business across borders. Indeed, values determine our subjective definition of rationality, or at the very least of common sense, as values are in most cases the result of personal experiences or of rules imposed on us for longer than we can remember.

Values in our minds are organized through systems of hierarchies: they are more or less important to us than other values. Conflict usually arises (even intraculturally) when two parties having contradictory values, and feel very intensively about them, interact. In cases where values are contradictory, but the intensity of the emotions toward these values by one or more of the parties involved is relatively low, concessions can take place. In the example above, if the American businessmen stick to their main value (performance) and the Saudi counterparts remain inflexible with regard to their seniority tradition, then no interactions will take place. At least one of the parties will have to make concessions for the deal to be concluded and the feasibility of that will greatly depend on how attached each one of the parties is to its own cultural values.

Another characteristic of values is that there is a difference between those that are desired and those that are desirable. Desired values are pragmatic and those espousing them take them into practice. Desirable values are those we believe in and ethically support, but we do not act upon. An example of a desired value could be that there are equal opportunities in recruitment for as long as a policy is put in place to support this value and it is reinforced. This same value becomes “desirable” if nothing is done to make sure there is equality in the workplace, no matter how strongly it is believed that this is how things should actually work. Needless to say, when two parties with contradictory values intend to make a deal, the level of ideology attached to them will determine the readiness of the parties to make concessions and therefore the likelihood of the deal being closed.

Subcultures

In general jargon, when the word “culture” is mentioned, reference is being made to the national culture or to the culture of a particular group that is set up in a specific geographic zone. Nevertheless, groups of people sharing values and mental programming can be constituted across borders and the links developed among them and across them can be as solid as those established by national links. These non-national cultures are called subcultures and they can group students studying or having studied at the same school, members of an extended family, members of the same profession or generation, individuals with the same sexual preferences, and, of course, people working for the same company.

The particular subculture that reunites people working for the same company is called corporate culture. People belonging to the same subculture develop similar sets of values and practices. In the specific case of corporate culture, these values and practices are usually reflected in the image the organization projects externally. Even though many authors including Geert Hofstede have questioned the very existence of corporate culture (the debate will be developed in chapter 5), practices shared by people acting in favor of a common institution generate a sense of commonality that reassembles them and produces a shared impression of belonging, which corresponds with that of the national culture.

Subcultures can be artificially created, like alumni associations, aiming to facilitate exchanges between selected members for the sake of a particular goal, through the achievement of compatible objectives; they can be naturally created, like that of people from the same generation; they sometimes require a specific meeting point to develop their rites and rituals, for example, Muslim believers traveling to Mecca; or they can reunite those identifying themselves with them online.

Belonging to a subculture makes communication easy, as codes, symbols, and interests are usually shared with others attached to the same group. The role of national cultures is similar to that of subcultures, in the sense that it reunites and provides a sense of identity by the exclusion of nonmembers.

Culture Stability and Cultural Change

Societies and subsocieties (cultures and subcultures) create and recreate norms of behavior and rules based on what is perceived as necessary to establish a good basis for growth and development and to ensure its own preservation.

People developing in closeness have to face similar problems and agree on joint actions to be executed, which aim to solve day-to-day or specific situations in an effective manner.

Let us consider an example. Say that a certain population has developed in an area where resources are rare and living conditions are extremely tough. This society will develop survival mechanisms that will be different from those existing in an area where resources are abundant. Habits will soon be formalized into norms and systems of rules, which will in time become the basis for the local legislation. After time, the practice of these legal precepts will be reinforced by experience and a shared notion of what is acceptable and what is not will be intersubjectively shared, creating a new and common mental programming. All social institutions are based on shared ideas of what is good and what is not so good for the society, and having established them to survive these same institutions are constantly reinforced by the same established patterns of convictions and shared ideology.

Cultures, therefore, tend to be stable, as they are the result of a series of attempts to respond and adapt to a particular environment. For as long as this response or series of responses to the environment work well, there is no need for change, perhaps other than a few alterations or small improvements that allow a most suitable adaptation.

The same pattern occurs in companies or in any other subculture. Let us consider a real-life example: furniture company IKEA. Among this company’s values, one could state creativity, fast reaction to environment, and teamwork. These values and system of values were the key success factors for the company’s business model and have ensured its progress through the years.

In order to reinforce these values, organizational systems and structures are created: recruitment and promotion systems, patterns like business cards that do not show the position of the employee within the company, a very flat organizational chart, and so forth.

The structures are supported by “norms” or rules and regulations that can be implicit or explicit and that will function as a compliance framework not only in day-to-day matters, but, in particular, in specific cases of conflict.

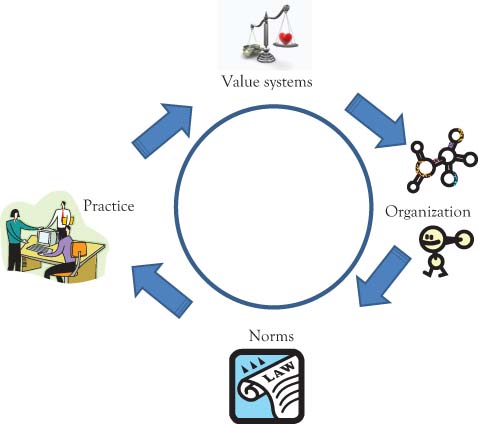

Finally, there is practice, or the application of the norms, which reinforces them through public example of what can be considered as “good” or “bad” (Figure 1.2).

The entire system, in fact, acts as a frequent reminder of the values that hold the subculture together, making cultures and subcultures perennial due to the cyclical reinforcement patterns through which they develop.

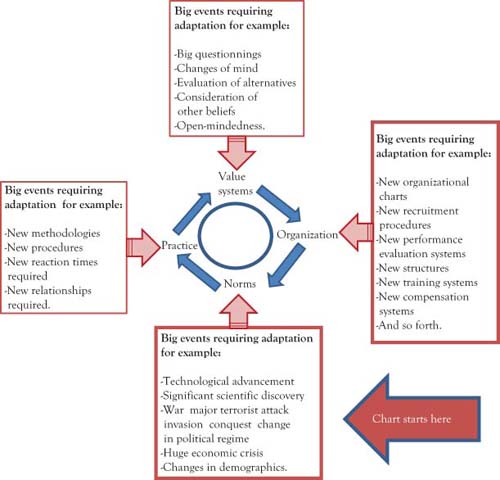

In other words, cultures tend to remain stable. But having said that, culture change does occur when a specific, major event takes place, resulting in the alteration of an otherwise relatively stable equilibrium. If something “big” and “unexpected” happens, the system will have to respond by changing the dynamics of the patterns.

Significant cultural change takes place in general when there is an important mutation in the environment that requires restructuring or reorganization of the social arrangements. A significant technological development, a revolutionary scientific discovery, a war, colonization, and a big pandemic are examples of changes in the environment that could cause cultural change because they could challenge the previously established mental programming and force people to think differently.

Examples of events that have changed cultures and patterns promoting cultural stability are countless (Figure 1.3). Let us mention just some of them.

Examples

- September 11, 2001: Most Americans discover that they may not be liked worldwide and the feeling of insecurity spreads across the country. More and more citizens vote for Republicans, people think in terms of terrorism, and laws are modified in order to respond to the generalized sense of fear.

- Henry Ford applies chain manufacturing to the car industry: having a car becomes less exclusive and people start moving more and faster. The GDP of industrialized countries grows exponentially, roads are created and others improved. The first step into distribution through big commercial chains starts to develop.

- The contraceptive pill becomes popular in Western societies by 1960: women discover their sexual activity is not necessarily linked to maternity any longer and they revisit their social role claiming independence from men and initiate a revolt that promoted laws such as the right to abortion and workplace equality.

- Turkey may soon enter the EU: The eternal search for “the common denominator” across all EU countries has been on since its early start. One of the attempts to generate the idea that there was a common past and a sense of unity across member states has been Christianity. The entrance of Turkey into the EU may challenge that belief and underline the need for further definitions. It might perhaps at some stage allow the entrance of Israel to the area, on the same grounds.

Cultural programming is difficult to change because all institutions (government, education, law systems, family structure, religion, habitat, etc.) are founded on values that sustain them. If cultural change is to be produced, then all these structures need to change.

Much energy is required to produce cultural change and not only brilliant ideologists, who find alternative ways of thinking, but also strong champions, ready to move actions forward, are required to produce social change.

Using This Information

This introductory chapter should help executives realize that their views might be subjective, even if most people in their culture agree with them.

There are certainties to which we stick, because we need guidelines for action in life, but these certainties may well be the extreme opposite in other parts of the world.

It can certainly be irritating having to coexist, operate, and even attempt to be profitable when dealing across borders; the exercise may well be exhausting, but it is worth the effort because when one executive understands another, it is easier to anticipate his or her behavior, make plans together, produce synergies, and build new opportunities as a team.

Exercises

1. List the principal values that constitute the mental programming of your own culture.

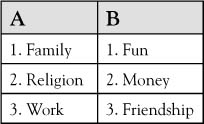

2. Reflect on some problems that could exist between two persons A and B, who have the following sets of values (hierarchically ordered) and who need to cooperate on a particular project.

How could these two people learn from each other in order to produce more synergy?

3. Imagine a situation in which a conflict of values could be observed in the industry of your choice. How could you intervene to solve it as a manager?