CHAPTER 2

Frameworks for Cultural Analysis

The Cultural Dimensions of Geert Hofstede

The Aim of This Chapter

This chapter aims at describing the basic and most widely used frameworks for cross-cultural analysis according to Geert Hofstede, who defined what he calls “dimensions” or general aspects in which cultures may be grouped according to commonalities in their mental programming.

Cultures in which gender roles are greatly differentiated and emphasized are known as “masculine” cultures—as opposed to “feminine” ones. Groups in which the collective interests overcome individual ones are called “collectivist” as opposed to “individualist.” Mental programmings in which hierarchy is a requirement for social order received the name of “high power distant,” and that in which a standard pattern of behaviors is preferred to innovative ones are called “high uncertainty avoidant.” Later in his career, Hofstede included the category of long-term versus short-term orientation to differentiate groups in which the emphasis is on saving before spending and those that think that debt encourages hard work.

Hofstede1 and those who followed his work ranked countries according to how they fitted into these categories and most of their research has evolved into more quantitative ranking of the same sort. In this chapter we will pay less attention to rankings and develop on the meaning, origins, and consequences of each stereotypical mental programming.

Frameworks for Cross-Cultural Analysis

Having discussed the origins of culture, its development, and its tendency to reinvent itself through the years in order to survive, we will proceed to the study of different areas in which cultures may differ. Several authors have intended to categorize cultures according to the collective mental programmings that each society promotes.

Some of the authors who have worked on the subject have collected their data through surveys, others have done so through material obtained during cross-cultural seminars with executives, some have business backgrounds, others are anthropologists, but they have all defined distinctive dichotomic areas in which they could rank cultures according to specific parameters. In this chapter and in the next two we will present the most famous work produced in this sense, and this will be the basis of analysis on which the rest of the book is built.

As previously mentioned, Geert Hofstede is a Dutch business anthropologist whose work in the area of culture and management is known around the world. During the 1960s and 1970s, he conducted surveys of IBM employees in more than 40 countries, asking them questions about their jobs and work settings. Based on these surveys, he identified systematic differences among countries.

He identified four basic dimensions of culture, which he called individualism/collectivism, power distance, uncertainty avoidance, and masculinity/femininity. In this chapter we will examine each of these dimensions, exploring their origin and developing on their potential consequences for cross-cultural management.

Based on the analysis of his dataset, Hofstede calculated a score for 40 different countries on each of the above-mentioned dimensions. These scores, he stressed, have no absolute value, but are useful only as a way to compare countries.

Individualism/Collectivism (IDV)

The first dichotomic area for study defined by Hofstede is individualism/collectivism.

Individualism describes the tendency of people to see themselves as individuals rather than as members of a group. In individualistic cultures, members are usually concerned with personal achievement, with individual rights, and with independence. In collectivistic cultures, people tend to see themselves first and foremost as part of a group, and may be more concerned about the welfare of the group than about individual welfare. They may value harmony and equality above personal achievement, and may be more concerned about an obligation and duty to other members of the group than about individual rights.

In collectivist societies, people are born to enlarge a family and reinforce a clan that will protect them for as long as they are faithful to it. Loyalty to the family is a key aspect of social recognition, as status will most certainly be linked to it. Each individual is part of a family, and safety and security are strongly dependent on each individual’s capacity to remain an appreciated member of the clan. This means that in collective societies “we” is more important than “I,” because a person alone will not succeed. Belonging to networks is the key success factor in life and family is considered as the primary and most important one of these networks.

In individualistic societies, on the other hand, each person is meant to take care of himself and of his immediate family. Individuals are brought up “not to need” anyone, as well as taught that “I” is more important than “we” because the main aspect of the mental programming is that one should not bother others or impose himself on others. A strong person should not be a charge on society or other people. Independence is valued. Actually, strength is based on personal initiatives and achievements, whereas in collective societies it is based on acceptance into groups.

Identity is therefore based on each person’s achievements and characteristics, rather than on the networks to which this person belongs. In collective societies, in contrast, identity is based on the social groups in which one is included. The school one has attended, the clubs, the family, the area or city in which each one was born, and so forth, place each person within the tacit social ranking the collectivistic culture has defined. Therefore, loyalty to these groups is paramount, as being excluded from them means becoming a pariah with no chance of success in life.

Attachment to companies and organizations is also experienced differently in collective and in individualistic societies. In the former, attachment to the workplace is moral more than legal. This means that the respect that the owner or boss obtains goes beyond the contractual agreement: very often the psychological contract exceeds in importance the value of the clauses that have been signed, and both employer and employee respect each other from their position out of a nonexplicit vow of loyalty and protection. In individualistic societies, attachment to work is more economic than ethical or affective, and therefore changes in jobs are more frequent and less traumatic. Market rules tend to influence behavior in companies more often than not.

The fact that in collectivist societies groups provide individuals with security and opportunities also allows them to intervene in the private lives of people. This means that the group will usually indicate what convictions the individual should defend, the friends of the individual should be approved by the group, and the individual is constantly reminded of the obligations he has vis-à-vis the group. Individual ideology must be coherent with group ideology. In individualistic societies, the opposite occurs: autonomy, truth, pleasure, and financial security are enhanced and supported by these cultures, not only as an indicator of success and good social behavior, but also and very specifically as a strong collective need for common growth.

Friendships in collectivistic societies are stable and long-term and also a reflection of the status of a person. People of higher classes or castes are not expected to mix with those of lower backgrounds because that would damage their image and therefore their capacity to remain within privileged circles. In individualistic societies, having diverse friends is possible and these do not necessarily have to mix as the private life of each person is expected to have different and diverse areas that do not necessarily interact (i.e., one person can have friends from a tennis club who are very wealthy, but also friends from camping who are not so wealthy, and still live two sorts of private lives with these groups never having to mingle).

The rankings produced by Hofstede can now be considered out of date, although his followers and disciples keep updating them through research that can be easily found in websites. Nevertheless, the concepts derived from the research are still valid.

As for the origins of individualism, those are arguable, but some hypotheses have been put forward to explain potential factors that could influence the development of this kind of thinking in a defined population.

Wealth could in some cases be the cause of individualism, as nations in which each person is wealthy enough not to depend on others could explain a mental programming in which people do not feel the need to justify their actions to the community. Wealth in some cases could also be the consequence of individualism, as the wealthier one becomes, the more independence is claimed.

Evidently, it would make no sense to say that all wealthy nations are individualistic and all poor ones are collectivistic, as there are examples that would quite clearly contradict these assumptions. In any case, mental programmings are not the result of the influence of one dimension alone, but the conjunction of an indefinite number of factors. Having said this, each dimension defined by Hofstede has been recognized as strongly affecting national culture’s mental programming.

For instance, there are many examples of rich nations that score high on collectivism: Japan and Singapore, just to name a few. Factors having potentially influenced the upkeep of a collectivistic mind in spite of economic development could be either historical (the social understanding that Japan could have never reconstructed itself after the Second World War had it not been for the serious loyalty and commitment shown by its inhabitants towards their peers), or philosophical (the Confucian principles which make the common good a priority over the individual good).

Religion certainly does affect the level of collectivism within a society. While Roman Catholicism conveys values that reinforce the image of the individual as dependent on the community, and does not necessarily celebrate the creation of wealth as a path to salvation, some Protestant sects like Calvinists conceive hard work, savings accumulation, and the possession of valuable goods without fiercely displaying them not only as the result of hard work itself (work being perceived as the activity that keeps man out of mischief), but also as a divine blessing. In Roman Catholic communities the rich are expected to give back to the poor (or to the Church), either in kind or in actions (or both). In Protestant communities, sharing is interpreted as a social cohesion activity, but yet everyone should be held responsible for their own actions and the development of their own wealth through work and effort.

Another potential explanation for the development of individualism is linked to industrialization. In view of the type of work required in agricultural societies, teamwork and loyalty to the family or close connections are meant to be beneficial for the deployment of tasks and actions. People work for those they know from very early in their lives, and codependence is necessary for survival. In industrialized societies, on the other hand, each person works for himself, by himself, and far from home (in cities) and for a stranger (a boss). Wherever social mobility is possible, it happens individually and not collectively through promotions. Therefore, countries that industrialized early in history tend to be more individualistic than those having had to rely on agriculture for longer. We will discuss matters relating to the new postindustrialized culture in subsequent chapters.

Power Distance (PDI)

Power distance captures the degree to which members accept an uneven distribution of power. In high power distance cultures, a wide gap is perceived to exist among people at different levels of the hierarchy. Subordinates accept their inferior positions, and are careful to show proper respect and deference to their bosses. Managers, in turn, may issue directives rather than seek broad participation in decision making. In low power distance countries, managers may be less concerned with status and more inclined to allow participation, and their employees may be less deferential and more willing to speak out.

Hofstede has demonstrated that the dimensions operate in similar ways at different levels of analysis, meaning not only that in a power distant society employees and their employers will act as described above, but also that all other structures work in a similar manner as well. Families in high power distant societies are generally led by fathers who control very strongly, and governments are more autocratic in their actions (even in democracies). In fact, high power distance societies are more prone to accept dictatorships than low power distance ones, because the image of a highly powerful presence has been built into the mental programming of their people from an early age (at family level, then through the school structure, then at work, etc.).

Origins of high power distance are uncertain, and so is the origin of most of the frameworks for cultural analysis, but a few hypotheses can be put forward to at least attempt to explain this behavior.

One of the hypotheses is that in benign, warm climates, access to food and basic goods was traditionally simple. No matter how harsh the situation, there has always been a way to survive without the need for strict discipline, planning, and sacrifice. Therefore, the use of structured forces and a firm discipline coming from someone else would be understood as a desirable factor that would motivate towards a collectively organized productive effort. In cold, difficult weathers, nevertheless, the necessary self-discipline “to put work before play” was paramount for each individual in order to survive. For instance, if someone in Finland decided that he would rather sleep than search for food one day, his survival would not be ensured for the next day: discipline had to come from within. This hypothesis explains therefore why generally (and there are many exceptions to this very general rule) in warmer climates people are more inclined to accept power distance than in colder ones. In colder climates, everyone trusts discipline and self-restraint, and therefore social order need not be imposed from the outside, whereas in warmer climates traditionally there has been a need to have someone instill it in spite of the will of others. In general, in high power distance countries wealth is concentrated within the higher stratas of society, whereas in low power distance countries it is more distributed. Money being very closely related to power, this commonality is not very surprising.

Another possible explanation for the origins of power distance is the size of countries. Smaller countries have allowed for plural participation very early in their development simply because it is easier to manage smaller groups of people than large ones. Extensive lands with diverse populations (i.e., Russia) call for centralized lines of command and generalist rules to be applied across the territory. Smaller structures can be run with the participation of many, as their size is still manageable.

We had mentioned some generalities that could sometimes explain the origins of power distance; nevertheless, it is worthwhile signaling that there are many exceptions to these rules. For instance, France and Belgium are both wealthy countries with relatively cold weather, but they still are high power distant. The causes for this exception to the very general rule can include historical facts such as the origin of the two countries in question as part of the Roman Empire. In fact, whereas Germanic societies were run by councils of citizens assembled to make decisions, all Romans would report to an Emperor who had full power. Another difference between the two ancient societies was that in the Latin world, heritage was divided between all brothers once the father of a family died, which implied that a son of a wealthy family would remain a landlord from birth to death. In contrast, in Germanic societies, it was the eldest son who inherited everything, leaving all younger siblings on their own, having to find their own ways to survive and therefore going overnight from belonging to a high society to having nothing to live upon. Social mobility has been a common feature within Germanic societies for a long time, whereas such has not been the case within the Roman Empire.

People in high positions from high power distance cultures in general use and promote the use of status symbols: bosses would not eat lunch at the same cafeteria as their employees, they would have private lifts, private parking slots, inaccessible diaries... Areas of the city would be very much divided according to social rank and power structures.

In high power distance cultures, authorities are either charismatic or constraining. Their power is not the result of authority and competence, but just the result of political games based on delusional demagogy, traditional access to hierarchy, or imposition by force. The person in charge is not necessarily the one that “can do the best job,” but the one that can have the masses follow him/her (more frequently him than her). Wage structures show significant differences in high power distance companies, whereas they do not in low power distance ones, in which everyone accesses the same level of education and where higher education is not always necessary to access power.

These reasons make it very clear why stable democracies are most frequently found in low power distance cultures, where it is not made obvious to everyone early on in their lives that there are undisputable ranks in life that ought not to be challenged. Statistics have shown that in high power distance cultures the ideological breach between labor and conservatives is highly polarized, whereas in low power distance cultures, the search for consensus between extremes is seen as a means to minimize exhausting and costly conflicts. Unions, for instance, are generally organized by companies or by governments in high power distance cultures, whereas they are less ideological and more practical in low power distance ones, in which their actions, by the way, are visible in day-to-day results.

There is certainly a link between religion and power distance. The Roman Catholic Church is visibly hierarchical in structure (with many ranks within the clerical order), and its philosophy is based on dogmas and absolute truths (i.e. the virginity of Holy Mary, the existence of a Holy Trinity, etc.). The Pope is formally considered as a full-power decision maker and rules apply worldwide. The Protestant tradition, on the other hand, is decentralized, has very little structure, and rules are adapted to local practitioners. Hence, Roman Catholic countries show in most cases high power distance as Protestant ones are more low power distant. In the case of the Muslims, even if their Church structure is not hierarchical in shape, their philosophy strongly supports high power distance behaviors, as stated in many passages of the Koran (i.e., “Men like to obey” or “Those who obey the Prophets obey God”).

Uncertainty Avoidance (UAI)

Uncertainty avoidance describes the extent to which people seek to avoid, or feel threatened by ambiguous or risky situations. Individuals in cultures characterized by high uncertainty avoidance may be risk averse in trying new ways of doing things, in starting new companies, in changing jobs, or in welcoming outsiders. They may emphasize continuity and stability rather than innovation and change. In cultures of low uncertainty avoidance, members may more readily embrace change, may show more initiative, and may be more accepting of different views and new ideas.

In low uncertainty avoidance cultures rules are ambiguous, unconventional behaviors are tolerated and there is solidarity towards those who do not belong to the mainstream. In high uncertainty avoidance cultures, there is a stronger need for rules, and there is stability, in particular in the work environment.

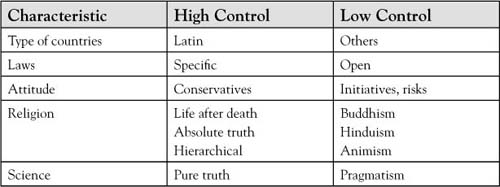

Latin countries are in general high uncertainty controllers, whereas Anglo-Saxons, Northern Europeans, South East Asians, Africans, and Indians show lower scores in this sense.

The roots of uncertainty avoidance could be found in the origins of Latin countries, namely in the Roman Empire and its unique legislative system that applied in all territories and across all the cultures in order to control them. Centralized rule derived from constitutional law, which is unique, undisputable, and supposed to reflect the general values that ought to be applied to as many cases as foreseeable. On the opposite extreme, there is the Anglo system of Common Law, which relies on jurisprudence, rather than on the rational formulas that would need to be applied to all situations everywhere.

A unique system with a generic law that develops into branches guarantees anxiety management, as there is always a formal support to the decisions being made. Strict rules provide with certainty as one knows what is good and what is bad and what the consequences of deviant behavior will be. Low uncertainty avoidance cultures conceive truths applicable “on the spot” that may not apply to other cases.

As far as religion is concerned, high uncertainty avoidance cultures stick to dogmas and absolute truths, whereas popular religions in low uncertainty avoidance cultures insist on initiative, self-guidance, and are more accepting of the evolution of the notion of morality across time and therefore their rules are modified rather more frequently than not. Roman Catholicism scores high in uncertainty avoidance, intermediary results are shown by Judaism and Islam, whereas Protestantism, Buddhism, and Animism are considered low uncertainty avoidance religions in view of their normative structure, which is less inflexible.

The same reasoning applies to knowledge. In fact, great scientists from high uncertainty avoidance cultures have based their theories on absolute truths and their mode of thinking is more deductive (they search for an undeniable fact and then derive all truth from it), rather than inductive (deriving truth from a common factor found in many cases). Examples of this difference are numerous: Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason (attempting to find the absolute rightful and all-applicable norms for ethical behavior no matter the circumstances), Marx, Weber, Descartes, etc.

The case study method as a research method and a pedagogic tool was created in Anglo-Saxon countries and that is where it has progressed. The same theories are perceived with discomfort in high uncertainty avoidance cultures, as they are based on specific, particular events rather than on generic, irrefutable ideas.

Delegation in companies is more likely to occur in low uncertainty avoidance cultures, as risks are perceived as part of the game. In high uncertainty avoidance cultures, delegating could be assumed to be a risky choice, in particular if power is given to people who are younger, of lower social rank, or diverse. The preference for “what has worked in the past” will be made in most cases. Foreigners, for instance, are more likely to have their chance of becoming managers in low uncertainty avoidance cultures than in high uncertainty avoidance ones, where they will be mistrusted in their capacity to perform their duties. Ambition is also considered as a desirable quality in low uncertainty avoidance cultures, which is not the case in high uncertainty avoidance ones. Technical ability is preferred to managerial skills in high uncertainty avoidance cultures, as the former can be measured and tested, whereas the latter are more subjective.

Failure is frightening in high uncertainty avoidance societies, and is seriously punished whereas it can be considered as necessary to evolve in low uncertainty avoidance ones. Working for big companies is preferred in high uncertainty avoidance cultures, and being an entrepreneur is frequently likely to be perceived as a last resort for someone avoiding unemployment.

Masculinity/Femininity (MAS)

Hofstede used the term “masculinity” to represent a cultural preference for achievement, assertiveness, and material success, and “femininity” to describe a greater importance placed on maintaining relationships, on caring for members, and on a high quality of life. In so-called masculine countries, work-related values tend to favor achievement and competition. In so-called feminine countries, firms provide more extensive services for the well-being of members, and emphasize overall welfare rather than bottom-line performance.

It is commonly believed within academic circles that the main origin of this difference lies in the way boys and girls are socialized since early childhood. Indeed, in societies in which male and female roles are very much differentiated, the general paradigm becomes masculine and in cultures in which girls and boys are brought up in similar ways, the feminine mental programming prevails.

For instance, in feminine societies, girls will have both mother and father as role models and so will boys. Both girls and boys will be responsible for helping set up the table and do the dishes, both boys and girls will learn to clean their rooms and boys and girls will be objects of the same professional expectations from their parents regarding their future career prospects. In masculine societies, expectations differ from an early age: girls are expected to learn how to run a household and take care of their families, whereas boys are brought up to be strong and powerful, have important careers, and earn money.

The result of such a differentiated education is that in feminine societies both men and women are expected to show their feelings to the same extent, both men and women have career aspirations, both men and women share household duties, and both men and women can access power positions in society. This is all much more relative in masculine societies.

As far as values are concerned, in masculine societies both men and women appreciate what are commonly referred to as masculine values: having a car with a huge powerful engine could be extremely appealing to men, and men possessing such an item would certainly seem appealing to girls. In feminine societies, having a car that is respectful of the environment could be important for both men and women.

The origins of femininity in cultures are uncertain, but it is quite common to find feminine societies in colder areas of the planet. Historically, in such latitudes, only one person being in charge of looking for food was not enough, that is why it is supposed that both women and men have been expected to assume responsibilities in “bringing home the bacon” for centuries. Equality in roles is in general more necessary when chances of survival in rough conditions need to be maximized as well as the size of the working population. Dissimilarity in gender roles is more frequent in warm countries because survival and growth of the population usually depended less on the action of humans on nature. In such a situation, women could afford to remain aside from certain practices because less manpower was necessary to survive.

In the specific case of ancient Scandinavia, Viking women have had to assume political positions while their husbands were abroad, which explains to some extent the historical evolution in countries such as Sweden or Norway, in which feminine values prevail.

In feminine countries, it is considered very important that everyone has what is necessary to live in dignified ways. Basic schooling, right to a home, and health are priorities for everyone. In masculine societies there is less solidarity and everyone is concerned for their families, relatives, or relations much more than for the common good. For similar reasons, feminine cultures are more prone to support ventures that protect the environment and to donate money to charities or international development activities.

With regard to the influence of religion on masculinity, it is possible to establish a link between the history of Judeo-Christianity and a historical evolution from masculinity towards femininity in religious paradigms. Indeed, in the Old Testament God appears as a powerful creature often referred to as a Judge that punishes and imposes a supranatural law, there are very few female characters, and the rules are very strict and well defined by the prophets. In Catholicism, there are already a few more feminine beliefs; Jesus is poor, modest, lives surrounded by fishermen and prostitutes, promoting love and forgiveness. The character of a woman, the Mother, Holy Mary brings an aspect of tenderness to his actions. In Protestantism, femininity is pushed one step further: the Mother is not a virgin any more, women can be ordained pastors and ministers, the notion of hell is less prominent, and communitarian work based on solidarity is extensively promoted. Divorce is allowed within the Church.

As for the influence of masculinity/femininity at work, in feminine countries both young men and young women take up challenging careers, whereas it is mainly men who do that in masculine cultures. In masculine countries it is more unusual to find women in higher positions, but the few that get there exhibit very aggressive behavior, as if this was the only way to compete with their male counterparts. There is less tension at work in feminine cultures and fewer industrial conflicts.

Long-term/Short-term Orientation (LTO)

With the increasing power of East Asian economies during the early 1980s, however, Hofstede wondered if his four indices had adequately captured what he perceived as the distinctive cultural characteristics of East Asian cultures: diligence, patience, and frugality. Based on further research, Hofstede added a fifth dimension that he referred to as long-term orientation.

Long-term orientation societies focus on the future, which means that they follow cultural trends towards delaying immediate gratification; therefore, they are money-saving societies. Short-term orientation societies focus on the past and on the present, respecting traditions and following trends in spending even if this means borrowing money.

Origins for this last dimension are not specified, but philosophical ideas found in Confucianism are compatible with the behavior shown by many Asian societies in this respect. Spending only once savings have been made is considered a sign of wisdom. In more action-oriented societies, spending on the spot to pay later can be understood as a motivator for action. It is sometimes to pay off debts that people take on overtime or make efforts to pay for what they have bought in the past.

Amongst regions scoring high in long-term orientation are China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea. Top short-term oriented countries are Pakistan, the Philippines, and Bangladesh. Western countries also are considered as short-term oriented.

Synthesis

Geert Hofstede, a business anthropologist, questioned himself about ways in which people from different cultures were different. Then, he took up a huge study, which consisted of interviewing employees of IBM all over the world.

Hofstede observed four different dimensions and categorized cultures with regard to their:

- Hierarchical distance,

- Reactions towards uncertainty,

- Individualism level,

- Masculinity level.

- And much later on relationship to the future (long-term versus short-term orientation)

- Characteristics of his classification are detailed below.

Individualism Versus Collectivism

Masculinity Versus Femininity

Hierarchical Distance

Uncertainty Avoidance

Using This Information

Managers aware of how their international counterparts think, feel, and react according to their mental programming can obtain significant competitive advantage over those who just act in front of others as they would at home and expect them to behave the same way they do.

It is nevertheless important to clarify that stereotyping is never good, and a culturally sensitive international manager who has been trying to act as he or she interprets one normally behaves in your country might find it offensive that you just try to classify or stamp on each one of his or her behaviors (i.e., saying out loud in an attempt to look open-minded, “Oh, you have to phone your parents in the middle of the day because you are collectivist”—it could well happen that the business person had to phone home in the middle of the day because his or her father had to undergo heart surgery that morning and he/she needs to know whether everything went well).

In most cases, when studying Hofstede’s frameworks, executives worldwide just think “Oh, that is why they act so weird! Knowing that, I shall change my attitude/adapt it so that we can deal with each other better.” It helps very much to understand where the other party is coming from and the frameworks allow us to formulate hypotheses that should allow us to tolerate, understand, and find avenues for conflict avoidance and resolution; rather than to stereotype and blame those who challenge our behavioral expectations.

Questions

1. Where would you place the following countries along each of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions? Give examples.

USA

China

France

Germany

Japan

Russia

2. Now go to http://www.geert-hofstede.com/ and find out how Hofstede classified each country. Do you agree with his scoring? Why/why not? Explain your answer.