Police investigation processes

practical tools and techniques for tackling cyber crimes

Abstract

The criminals and terrorists behind contemporary cyber threats to society are well organized, and the impact on the victims from their activities can be devastating. Therefore, the complex nature and sophistication of cyber crime and cyber terrorism demands a dedicated response, especially from investigators who are critical to the success of tracking cyber criminals and bringing them to justice. This chapter considers the core investigative competencies which provide the practical tools and techniques for conducting professional cyber investigations. The key investigative skills of decision making, problem solving, developing hypothesis, embracing innovation, and the importance of contact management, are all explored in the context of contemporary cyber investigations.

Introduction

The Internet has brought, and will continue to bring, huge benefits to industry, individual citizens and their communities around the world. Unfortunately, there are a small but increasing minority of people who seek to exploit new opportunities for their chosen criminal purpose. Cyber criminals are quick to spot the potential vulnerabilities of new technologies and use them to commit offences, or try to frustrate detection of their activities (HM Government, 2011). Cyber crime and cyber terrorism is no longer about those who simply seek to access computer systems to prove it can be done. Cyber threats are real and damaging. The criminals and terrorists behind contemporary cyber threats to society are well organized, and seek to take advantage of those using Internet services. Whether this is for financial gain, in pursuance of extremist ideologies or as threats to children, the impact on the victims can be devastating. The most vulnerable members of our society are all too often the victims of cyber crimes—from young people threatened by bullying or sexual predators, to the elderly who provide easy prey for organized fraudsters (HM Government, 2010).

To tackle the phenomenon of cyber crime and cyber terrorism, governments across the world have invested substantial resources in homeland security, resulting in significant law enforcement and intelligence agency responses to online threats. Designed to detect, deter and disrupt all manner of cyber-related hazards, new cyber policing units have been rapidly established to investigate cyber crimes (Awan and Blakemore, 2012). Such investment fulfils the first duty of governments to protect the security and safety of their country, citizens and their wider interests. The focus and investments made to tackle cyber crime and cyber terrorism are welcomed but no one in authority can afford to be complacent. The threat from cyber crime and cyber terrorism is constantly evolving—with new opportunities to commit “old” crimes in new ways as well as high-tech crimes which did not exist several years ago (HM Government, 2011). Cyber criminals are becoming more sophisticated, and they continue to develop malicious software and devise improved methods for infecting computers and networks (HM Government, 2011). Cyber criminals are also continually adapting their tactics as new defenses are implemented. To counter new cyber criminal activities, law enforcement agencies must continue their efforts to ensure cyber space is a hostile environment for them to operate.

The complex nature and sophistication of cyber crime and cyber terrorism demands a dedicated response, especially from investigators who are critical to the success of tracking cyber criminals and bringing them to justice. Therefore, this chapter shall focus upon the role of the cyber investigator, addressing the challenges they encounter and the methods, models and investigative doctrine they should use to become an effective cyber detective. Although this chapter does not focus on the technical role and responsibility of those specialist hi-tech investigators, it will provide them with the tools and techniques to develop their core investigative skills. This chapter shall also serve as a timely reminder for the police officer and traditional criminal detective investigator, many of whom now find themselves thrust into investigating online crimes with little or no training and experience in this domain.

This chapter consequently considers five pertinent areas of core investigative competencies which provide the foundations upon which professional cyber investigations, indeed all criminal investigations, should be conducted. The key investigative skills of decisions making, problem solving, developing hypothesis, embracing innovation, and the importance of contact management are all explored in the context of contemporary cyber investigations.

Investigative Decision Making

Making sound judgments is a core role and important attribute of any successful cyber investigator, particularly those Senior Investigating Officers (SIO) charged with the responsibility of managing and directing large-scale investigations. Effective decision making, particularly at the very outset of cyber investigations, will ensure opportunities are not missed and potential lines of enquiry are identified and rigorously pursued. In reality, law enforcement officers who are engaged in the early developments of an investigation do have to cope with a lack of sufficient information to begin with, and some important decisions may need to be made quickly and intuitively. According to Cook and Tattersall (2010)

A key skill involves the tenacity of the investigator being able to recognise when there is insufficient time to gather further information. Intuition however, derives from knowledge and experience and can be prone to bias, therefore investigative decisions must always be based on reasoning and analysis to avoid subjectivity (p. 33).

The commencement of a cyber-based investigation, especially any complex investigation which may be high profile and is being conducted under the glare of the media will be frenetic. Nothing should prevent the professional cyber investigator from being able to progress their tasks at a pace which ensures they can perform their roles to the highest professional standards. Investigators must be afforded the time to complete their investigations and this requires them to not get caught up in the pace of the wider investigation but to slow things down where necessary. This approach will assist key decision making processes which is vital to the success of any investigation. According to Cook and Tattersall (2010):

Investigative decision making must always be directed at reaching goals or objectives. In order to ensure that good decisions are made towards achieving particular aims, it should at the earliest point in the investigation be determined what the primary investigative objectives are. A generic example of how such objectives may look are as follows:

• Establish that an offence has been committed or has not been committed.

• Gather all available information, material, intelligence and evidence.

• Act in the interests of justice.

• Rigorously pursue all reasonable lines of enquiry.

• Conduct a thorough investigation.

• Identify, arrest and charge offenders.

• Present all evidence to prosecuting authorities (p. 34).

It is effective practice to record the primary investigative objectives of a cyber investigation into an investigative policy decision making log at the early stages of the investigation. This ensures that rationale for key investigative decisions are captured at the time they were made in light of all information that was readily available. The primary investigative objectives must be disseminated to all other officers and investigators who have an operational requirement to know the strategic direction of the cyber investigation. During the process of investigations, investigators and senior officers will be using their skills to analyze, review and assess all the information and material that is available. This is an extremely important process as the accuracy, reliability, and relevance of material being obtained will influence decision making. Any changes to the primary investigative objectives should be recorded and again disseminated to all officers progressing the investigation. According to Caless et al. (2012):

The golden rule is for investigators to apply what is known as the ‘ABC’ principle throughout the life of an investigation as follows:

B. Believe nothing

C. Challenge and check everything (p. 271).

All investigators, especially those progressing complex cyber investigations, must ensure that nothing is taken for granted and it cannot be assumed that things are what they seem or that processes have been performed correctly (Caless et al., 2012). Looking for corroboration, rechecking, reviewing, and confirming all aspects of the investigation are hallmarks of an effective cyber detective, and shall ensure that no potential line of enquiry is overlooked during a dynamic and fast-moving cyber investigation.

Investigative Problem Solving

Essential to the core investigative skills of decision making are elements of problem solving. A logical approach to making decisions to effectively resolve problems within cyber investigations is demonstrated by the Cyber Investigators Staircase Model (CISM). Adapted for law enforcement from leadership and management models, the CISM contains important and sequential elements to ensure effective problem solving shown in Figure 4.1.

The model works on the basis that it is preferable to choose a particular course of action out of a range of possible “options” (Staniforth, 2014). The basic point here is that a cyber investigator should not assume there is only one option available, there are always alternatives, especially in cyber investigations which have a tendency to quickly gather large volumes of data. Information lies at the heart of an investigation and gathering sufficient information helps to populate the number of options which can then be worked through a decision making processes as to which option is the most compelling.

In order to gather and collect information to satisfy the requirements of Step 2 on the CISM, a set of interrogative pronouns, commonly known in the law enforcement field as the “5 × WH + H” method—Who, What, When, Where, Why + How can be put to good use (Cook and Tattersall, 2010). This formula helps to organize the investigative information and to identify where there are knowledge gaps. For a cyber crime investigation this may look as follows:

• Who is the victim? – Victim details and why this victim?

• What happened? – Precise details on incident/occurrence

• When did it happen? – Temporal issues such as relevant times

• Where did it happen? – Geographic locations, national/international?

• Why did it happen? – Motivation for crime or terrorism

• How did it happen? – Precise modus operandi details

This information can then be developed into a useful investigative matrix which will help identify the gaps in information by setting out all the relevant details in a logical sequence which is easily understood. The matrix can then be populated as the cyber investigation develops and used as a source of reference for the basis of applying the CISM and any associated decision making that is required. The matrix must be a living document, being regularly updated as the investigation progresses. The matrix can then be cross-referenced to decisions as and when they are made and will serve to illustrate just what was known or not known at the time any particular decision was made. This is a very important point for justifying why a particular course of action was, or was not, taken by the investigator.

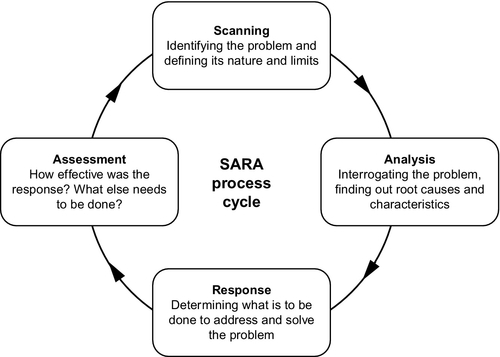

The 5 × WH + H structure can also be useful when being briefed or updated about an incident or set of circumstances. Investigators can pose questions using the 5 × WH + H headings in order to establish sufficient detail about what may already be known. The method can be used to ensure clear and concise information is supplied in a systematic rather than a random approach. To support investigators engaged in progressing complex cyber cases, the Scanning, Analysis, Response and Assessment (SARA) model for problem solving, shown in Figure 4.2, provides an effective process for police officers (Caless et al., 2012).

The SARA analytical methodology offers a staged process for identification, understanding and resolution of specific problems through scanning, analysis, response, and assessment. The four-staged process is used by a number of law enforcement agency practitioners to provide a framework to guide them through the challenges of finding solutions to complex problems. It is an approach that works well for problems and challenges arising during cyber crime and cyber terrorism investigations. Of course, in reality, no theoretical model can cover all potential issues when attempting to dynamically solve problems during complex cyber investigations with international dimensions, but the model provides a methodical approach that shall support and inform key investigative decisions (Staniforth, 2014). It must also be recognized that stages of the SARA cycle may overlap, repeat themselves and some can remain undeveloped while others move to completion. This mirrors the pace of cyber investigations as some strands of a complex investigation can develop rapidly, while others require more time to progress. It is also acknowledged that when addressing problems police officers do not go steadily round the four stages of the SARA cycle, but instead cut across some stages when experience informs them it is expedient and in the interests of the wider investigation to do so. That being said, the SARA cycle provides a methodical approach upon which to frame problem solving activity. Those officers charged with the responsibility of investigating cyber-related crimes would be well advised to adopt such a model which provides confidence and clarity to their problem solving decision making processes.

Developing Investigative Hypothesis

Decisions to effectively progress cyber investigations may have to be based on or guided by a hypothesis. For cyber investigations, Cook and Tattersall (2010) recommend that:

a hypothesis is a proposition made as a basis for reasoning without the assumption of its truth and supposition made as a starting point for further investigation of known facts. Developing and using hypothesis is a widely recognised technique amongst criminal investigators which can be used to try to establish the most logical or likely explanation, theory, or inference for why and how a cyber crime has been committed. Ideally, before cyber investigators develop hypothesis there should be sufficient reliable material available on which to base the hypothesis such as details of the victim, precise details of the incident or occurrence, national or international dimensions of the offence, motives of the crime and the precise modus operandi (p. 43).

Of course, knowledge and experience of previous cases will also greatly assist in constructing relevant hypothesis. Generating and building hypotheses is an obvious and natural activity for cyber investigators, particular during the early stages of an investigation. Clearly, if there is sufficient information or evidence already available then there will be no need to use the hypothesis method. However, cyber investigators are being increasingly called to establish the most basic of facts at the commencement of investigations, such as whether a crime has been committed or not. Hypotheses are important to provide initial investigative direction where there is little information to work with. All cyber investigators must “keep an open mind” and remember that it is better to gather as much information as possible before placing too much reliance on any speculative theory (Cook and Tattersall, 2010). It is a mistake for cyber investigators to theorize before sufficient data is collected as it is easy to fall into the trap of manipulating and massaging facts to suit theories, instead of ensuring that theories suit the facts.

Cook and Tattersall (2010) provide professional police investigative practice guidance which is commonly used by law enforcement officers across the world. Their advice, based on extensive investigative experience in the UK, includes checklists for consideration when building hypothesis. Cook and Tattersall (2010) recommend that when developing theoretical assumptions, cyber investigators would be well advised to give due consideration to the following:

• Beware of placing too much reliance on one or a limited number of hypotheses when there is insufficient information available.

• Remember the maxim ‘keeping an open mind’.

• Ensure a thorough understanding of the relevance and reliability of any material relied upon.

• Ensure that hypotheses are kept under constant review and remain dynamic, remembering that any hypothesis is only provisional at best.

• Define a clear objective for the hypothesis.

• Only develop hypothesis that ‘best fit’ with the known information and material.

• Consult with colleagues and experts to discuss and formulate hypothesis.

• Ensure sufficient resources are available to develop or test the hypothesis (Cook and Tattersall, 2010, p. 45).

Progressing cyber investigations is a collaborative effort and police officers must consult, listen and consider the advice and guidance provided by specialist hi-tech investigators. Any cyber investigator who ignores specialist advice does so at their peril.

Investigative Innovation

Cyber crime and cyber terrorism investigators, especially those officers leading and managing investigative teams, must be capable of having or recognizing good ideas and using them to make things happen. This is an extremely useful skill for any police investigator progressing traditional criminal enquiries but is essential for cyber investigators given the sheer size, scale, scope and sophistication of online criminality. To detect, deter and disrupt cyber criminal activity all cyber investigators need to draw upon their experience, skill and ingenuity. Innovative approaches to tackling cyber crime and cyber terrorism are essential, and investigators should bring or introduce new methods and ideas for implementation as part of the investigative process.

It is imperative that cyber investigators and senior leaders create an effective team working environment. Every lesson of every cyber investigation has revealed that no one single investigator can effectively progress cyber investigations on their own. Only by working together and bringing individual skills and expertise to bear in concert with one other, will a team of cyber investigators be able to tackle cyber crime and cyber terrorism effectively. Therefore, officers engaged in investing cyber crimes must create a consistent culture of positively finding solutions and new ideas to problems and challenges. The need to share and support new ideas is a necessary component of any cyber investigative team and innovative ideas that enliven and arouse the spirit of investigators is essential. Assumptions based on traditional beliefs and prehistoric knowledge should be challenged in favor of finding new ways of doing things, with new tactics, techniques and technology. This is not to say that traditional methods do not work when they are clearly tried and tested, but adopting a more radical, less risk averse approach and embracing innovative ideas to bring cyber criminals to justice is absolutely necessary for the continued professional development of cyber crime policing policy, practice and procedure.

Investigators Contact Management

Within policing, and especially in cases of issues related to the investigation of cyber crime, one of the key points from which all perceptions of the police derives is that of the contact between the public and the police (Caless et al., 2012). This first contact with the public, whether victims or witnesses of cyber crimes, is critical for the effective delivery of cyber policing at every level. Whether this contact is by calling the police via telephone or meeting a police officer in person, for the member of the public initiating the interaction and coming forward, it is a time of crucial importance. The member of the public contacting the police, implicitly or explicitly to report cyber crime, asks themselves three questions as follows:

• Will my concern be taken seriously?

• Will I receive the service I expect?

• Will I get satisfaction from what has occurred?

If this initial contact is well handled, then the subsequent actions are based on an established foundation. To tackle all manner of cyber criminality, law enforcement agencies require the full support of the public, so when members of the public have the courage and conviction to come forward to report and discuss cyber crime issues, police officers must have due regard to positive contact management. Cyber crime contact management must be a priority not just for those law enforcement officers who are public-facing, but for all of police officers, including cyber crime investigators. By simply ensuring that reports from the public are appropriately prioritized, taken seriously, and the member of the public is kept informed and is satisfied with the police response, will best serve the efficiency of the initial investigation.

All police officers must understand that first impressions really do count. The courteous, professional and positive contact with members of the public is important for all policing activities, including the investigation of cyber crime. Above all else, matters reported to the police regarding cyber crime must be taken seriously. There is no room for complacency in tackling cyber crime. When dealing with reports concerning cyber crime, all officers must:

LISTEN (Staniforth, 2014) to members of the public:

Listen to citizens and take their concerns seriously

Inspire confidence and provide reassurance

Support with information, advice and guidance

Take ownership and record citizen concerns

Explain what you shall do and why

Notify supervision and report concerns

During all cyber investigations, the public must be put first. The victims of cyber crimes must be managed professionally and specialist care and support provided as required. Complainants of cyber crimes must be regularly updated as to the progress of the investigation. By listening to members of the public and providing a police service of the highest professional standards will increase confidence of the public in the law enforcements commitment and determination to tackle cyber crimes.

Investigating Crime and Terror

When Metropolitan Police officers raided a flat in West London during October 2005, they arrested a young man, Younes Tsouli. The significance of this arrest was not immediately clear but investigations soon revealed that the Moroccan born Tsouli was the world’s most wanted “cyber-terrorist” (Staniforth and PNLD, 2009). In his activities Tsouli adopted the user name “Irhabi 007” (Irhabi meaning “terrorist” in Arabic), and his activities grew from posting advice on the internet on how to hack into mainframe computer systems to assisting those in planning terrorist attacks (Staniforth, 2012). Tsouli trawled the internet searching for home movies made by US soldiers in the theatres of conflict in Iraq and Afghanistan that would reveal the inside layout of US military bases. Over time these small pieces of information were collated and passed to those planning attacks against armed forces bases. This virtual hostile reconnaissance provided insider data illustrating how it was no longer necessary for terrorists to conduct physical reconnaissance if relevant information could be captured and meticulously pieced together from the internet.

Police investigations subsequently revealed that Tsouli had €2.5million worth of fraudulent transactions passing through his accounts which he used to support and finance terrorist activity. Pleading guilty to charges of incitement to commit acts of terrorism Tsouli received a 16-year custodial sentence to be served at Belmarsh High Security Prison in London where, perhaps unsurprisingly, he has been denied access to the Internet. The then National Coordinator of Terrorist Investigations, Deputy Assistant Commissioner Peter Clarke, said that Tsouli:

provided a link to core al Qa’ida, to the heart of al Qa’ida and the wider network that he was linking into through the internet”, going on to say: “what it did show us was the extent to which they could conduct operational planning on the internet. It was the first virtual conspiracy to murder that we had seen (Staniforth and PNLD, 2013).

The case against Tsoouli was the first in the UK which quickly brought about the realization that cyber-terrorism presented a real and present danger to the national security of the UK. A decade has now passed since the arrest of Tsouli, and law enforcement practitioners have come to understand that the internet clearly provides positive opportunities for global information exchange, communication, networking, education, and is a major tool in the fight against crime, but a new and emerging contemporary threat continues to impact upon the safety and security of the communities they seek to protect. The Internet has been hijacked and exploited by terrorists not only to progress attack planning but to radicalize and recruit new operatives to their cause (Awan and Blackmore, 2013).

The case against Tsouli served to raise concerns amongst security professionals that there was a distant lack of understanding by police investigators between the disciplines of crime and terrorism, at both a strategic and tactical level. To provide clarity, investigators must understand that first and foremost terrorism is a crime, a crime which has serious consequences and one which requires to be distinguished from other types of crime, but a crime nonetheless. Individuals who commit terrorist-related offences contrary to domestic and international law are subject to the processes of a criminal justice system and those who are otherwise believed to be involved in terrorism are subject to restrictive executive actions. However, the key features of terrorism that distinguish it from other forms of criminality are its core motivations. Terrorism may be driven politics, religion, or a violent and extremist ideology (Staniforth, 2012). These core objectives are unlike other criminal motivations such as for personal gain or in the pursuit of revenge. Terrorists may be driven by anyone or any combination of the core motivations but the primary motivator is political. Terrorism is a very powerful way in which to promote beliefs and has potentially serious consequences for society. If allowed to grow and flourish, terrorism can undermine national security, it can cause instability to a country, and in the most extreme of circumstances can lead to war. Terrorism seeks to undermine state legitimacy, freedom, and democracy. These are a very different set of motivations and outcomes when compared against other types of crime. This is the very reason why tackling terrorism nationally and internationally is an endeavor led by intelligence agencies of government, regarded as “higher policing” activity within the secret and sensitive domain of nation security. The primacy afforded to the intelligence apparatus of governments to tackle terrorism therefore means that countering terrorism is different to investigating other types of criminality. The potential impact on a nation’s security is why terrorism, in all of its forms, requires a covert, pre-emptive and intelligence-led approach to prevent it.

While it is important for the cyber investigator to distinguish between crime and terrorism, it must also be recognized that both cyber crime and cyber terrorism investigations are very different to other types of traditional criminal investigations. There are three key differences to consider, first of all, cyber investigations have a global reach. Every major cyber crime or cyber terrorism investigation has the potential for enquiries to be conducted in multiple locations. One enquiry for one single cyber terrorist for example, may lead investigators to several police jurisdictions in separate regions of the same country and then to numerous countries in Europe, the Middle East, Africa and around the world as investigators pursue lines of enquiry. Secondly, the scale of an investigation can rapidly grow as multiple victims and suspects are identified residing anywhere in the world. To resource this level of investigation where there is a critical requirement for intelligence and evidence capture can quickly go beyond the capacity of traditional investigative teams established for the most serious of criminal offences. Thirdly, the complexity of such an investigation is not only evident in the cross-border of trans-national protocols but that intelligence and evidence is being collected simultaneously. Evidence is required to support successful prosecutions and intelligence may be required urgently to support ongoing covert operations for intelligence agencies around the world (Staniforth and PNLD, 2009).

Conclusion

The impact of cyber crime and cyber terrorism has forced intelligence and law enforcement agencies across the world to enter into a new era of collaboration to effectively tackle cyber threats together. Despite cyber investigations having reach, scale and complexity beyond that experienced in other large-scale enquiries, their effectiveness relies upon thorough investigative police work. This chapter serves to illustrate that although investigators in specialist cyber crime and counter-terrorism units do have unique skills and abilities to perform their roles, it is their attention to detail combined with a professional and practical application to their role as an investigator which is critical to their success. Focusing upon the core investigative tools and techniques described in this chapter is essential for the effective investigation of cyber crime and cyber terrorism.

Cyber crime shall continue to evolve at a rapid pace and all security practitioners must recognize that they are now operating in a world of low impact, multiple victim crimes where bank robbers no longer have to plan meticulously the one theft of a million dollars; new technological capabilities mean that one person can now commit millions of robberies of one dollar each (Wall, 2007). Paradoxically, effective contemporary cyber investigations rely upon a collaborative, multi-disciplinary and multi-agency approach where police detectives, hi-tech investigators, forensic analysts and experts from academia and the private sector work together to tackle cyber threats. The complex nature and sophistication of cyber crime and cyber terrorism continues to demand a dedicated and determined response, especially from investigators who are critical to the success of tracking cyber criminals and bringing them to justice. A professionally trained, highly skilled cyber investigative workforce is now required. This workforce must prepare and equip itself for the cyber challenges that lie ahead and the reading of the chapters which follow provide an excellent starting point. Most importantly however, cyber crime and cyber terrorism investigators—no matter how complex and technical cyber investigations become in the future—must develop their expertise founded upon the core investigative competencies outlined in this chapter.