Understanding the situational awareness in cybercrimes

case studies

Abstract

Situational understanding and attack attribution of cybercrimes is one of the key problems defined by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (2009) for cyber security research. In particular, situational understanding is critical for a number of reasons: improved systems security; improved defense against future attacks; attack attribution; identification of potential threats; improved situational awareness. This paper shows that a clearer understanding of the motivations and intentions behind cybercrimes/cyber terrorism can lead to clearer situational understanding and awareness. Five pertinent real-life scenarios are considered and a taxonomy which focuses on the motivations and intent of the cybercrimes is outlined. The development of the taxonomy highlights a clear need to create an agreed set of definitions and understandings for improved cyber security defense. The very fact that the hacking is happening across times zones and jurisdictions means that it is easier for hackers, hacktivists, and cyber criminals, etc., to continue their attacks. There is a need for clear communication strategies and intelligence about the attacks to be shared between not only by affected countries/governments, but also networks across the globe to strengthen security networks against future attacks and risks. A knowledge repository of cybercrime, which makes use of this simple taxonomy design, could help toward strengthening the plight against cybercrime.

Introduction

As already mentioned in chapters throughout this book (see Chapters 1, 3, 5, and 13) cybercrime and cyber terrorism are increasingly important concerns not only for policy makers, but also businesses and citizens. In many countries, societies have come to rely on cyberspace to do business, consume products and services or exchange information with others online. Between 2000 and 2012, the growth of Internet users has been estimated at 393.4% (World Internet Usage and Population Statistics, 2012). Yet, Khoo Boon Hui, former President of Interpol, announced in May 2012 a figure of €750 billion is lost globally per year due to cybercrime. Cybercrime not only costs money, it also jeopardizes critical infrastructures, citizens and businesses, as well as security, identity and privacy.

This chapter shows that a clearer understanding of the motivations and intentions behind cybercrimes/cyber terrorism can lead to clearer situational understanding. Furthermore, it provides frontline agencies (LEAs) with the capability to recognize and act on cybercrime and cyber terrorism situations through the design of a taxonomy model. Situational understanding and attack attribution of cybercrimes is one of the key problems defined by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (2009) for cyber security research. In particular, situational understanding is critical for a number of reasons:

• Improved defense against future attacks

• Attack attribution

• Identification of potential threats

• Improved situational awareness

This chapter proposes that the lessons learnt from real-life scenarios can be used to create a knowledge repository which can support a clearer understanding and knowledge framework for cybercrime. The prerequisite for a knowledge repository is the development of a taxonomy which will help to develop the situational understanding behind the cybercrimes.

Leaning toward a sociological perspective, this chapter considers five pertinent cyber-crime cases and makes use of a taxonomical classification method to cluster these based on perceived intention/motivation of the attack. This chapter also makes use of Akhgar's (1999) concept of knowledge management—where knowledge is built upon a continuum of data which is first turned into information through an interpretation of the context using domain intelligence and then information into knowledge (which is an abstraction of the learning process).

To further support the need for a taxonomy for the situational understanding of cybercrime, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (2009) stresses a need for a “people layer knowledge” which consists of data outside networks and hosts (p. 68). The taxonomy is developed with this in mind. The Department for Homeland Security roadmap for cyber security research report also highlights a need for analysis on:

repeated patterns of interaction that arise over the course of months or years, and unexpected connections between companies and individuals. These derived quantities should themselves be archived or, alternatively, be able to be easily reconstructed (US Department of Homeland Security, 2009, p. 70). Whilst also stressing that “situational understanding requires collection or derivation of relevant data on a diverse set of attributes”

(US Department of Homeland Security, 2009, p. 73).

As it has been noted through this book, cybercrime has become an everyday problem for internet users. In 2012 in the US the Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) who partners with the FBI received 289,874 consumer complaints resulting in a total loss of over $500 million dollars. Clearly as well as companies, individuals across the globe are subject to cyber-related crime. There are multiple motivations for carrying out cybercrime: Moral, financial, political, for exploitation, self-actualization, and promotion, and these are outlined below.

However before outlining the case studies it is important to define cybercrime. For the purposes of this work, the Association of Chief Police Officer e-Crime Strategy definition of E-crime (2012) will be used: “The use of networked computers or internet technology to commit or facilitate the commission of crime.”

According to ACPO (2012):

The internet allows criminals to target potential victims from anywhere in the world, and enables mass victimization to be attempted with relative ease…The internet provides the criminal with a high degree of perceived anonymity, as well as creating jurisdictional issues that may impede rapid pursuit and prosecution of offenders. In addition there is not yet a clear distinction between issues that are best dealt with through better regulation and those that require law enforcement action.

(APCO, 2012, p. 6).

This statement is particularly applicable to the case studies outlined below. The very fact that the hacking is happening across times zones and jurisdictions means that is it easier for hackers, hacktivists, cyber criminals, etc. to continue their attacks. It also helps to emphasize a need for clear communication strategies and intelligence about the attacks to be shared between not only by affected countries/governments, but also networks across the globe to strengthen security networks against future attacks and risks.

It is also important to make clear that the following chapter outlines some of the activities in cyber space—without prejudice. The authors are neither in support nor against the activities summarized below. The outlined cases show the variation in the motivation behind cybercrimes and terrorist use of the internet, and also show the potential difficulties for taxonomizing motivations behind attacks. It is also important to highlight the difference in jurisdiction across the world in relation to the definition of cybercrime (see Chapters 1 and 3). There is for instance a fine line between covert operations and terrorist attacks depending on where in the world the activity is occurring. Therefore, this chapter does not intend to address the issues of law and legislation behind the activity. The cases that have been used are summarized by outlining the information that is publicly available about them. They are followed by an overview of the strategic responses from the UK, US and EU and then a threat assessment is discussed.

Taxonomical Classification of Cybercrime/Cyberterrorism

There are a number of taxonomies developed in relation to cybercrime and activity. Other taxonomies for cybercrime concentrate on the characteristics of attacks (Lough, 2001) whilst Howard and Longstaff (1998) taxonomy accounts for motivations and objectives and consists of five process stages. However, a key problem in the area of cyber security is the lack of agreed terminology across different organizations, research disciplines and approaches, and stakeholders. This taxonomy therefore attempts to overcome linguistic barriers by using nontechnical language. Taking a human-centric approach this taxonomy focuses on the situational understanding of cybercrime and helps to foster the practical implementations of countermeasures by focusing on intentions (and circumstances) surrounding the cybercrimes.

The proposed taxonomy below relates to the perceived motivations/intentions for cybercrime and attacks and therefore does not focus on the technical considerations of cybercrime. The taxonomy needs to be elaborated, not only as a list of words but also to reflect the attributes (and their inter-relationships) that are key to all the target user communities—for example law enforcement agencies, especially investigative officers.

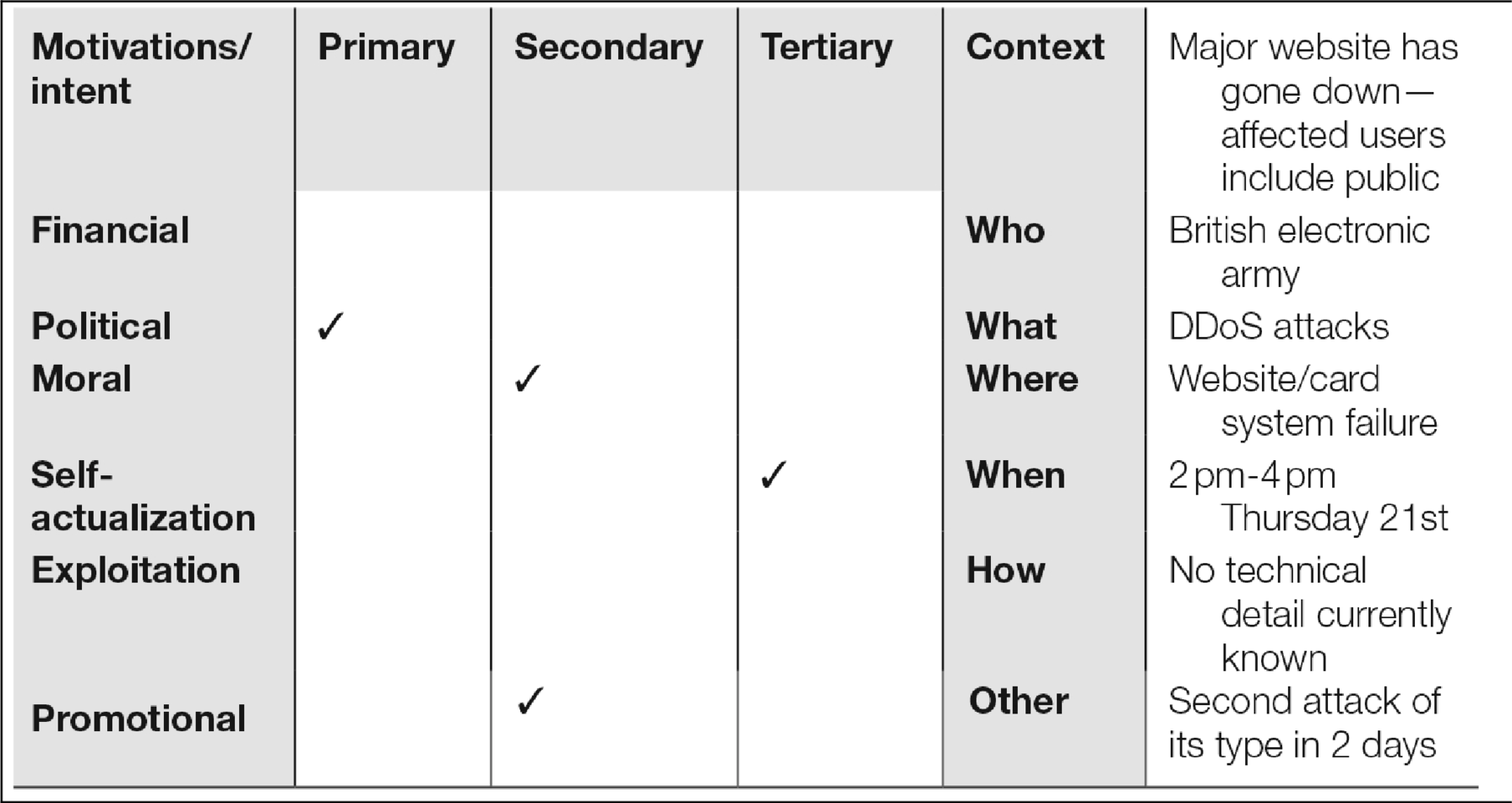

Whilst this is a starting point for a categorization process there is room for development as cyber security demands change and develop. Currently it is not exhaustive and a limitation could be the lack of room for technical detail, however in its current form it helps to establish the perceived motivations behind cyber-attacks which in turn provides basis for situational understanding (Table 9.1).

For operational use and in order to create a repository—the grid above can be used for each cybercrime incident. A mock example has been included to show how it could be used. The first section of the grid enables a tick box system where multiple motivations may be ticked. For instance a decision may be made that the case is primarily politically motivated but has moral and promotional motivations (see example above). Different investigative officers may have different opinions or evidence about the motivations—there is no limit on how many boxes can be ticked—especially given that some cases may be complex in nature—although it is recommended that decisions are made about the primary, secondary and tertiary motivations rather than clustering motivations into one category. It is possible that there are no secondary or tertiary motivations—in these cases the boxes can be left blank. Information relating to the cybercrime case can be included to the right of the table and can be as detailed as is necessary. The “context” and “other” boxes allow for any field notes or important information relating to the case to be included. The “who” box relates to potential suspects and can also include potential victims. If information is not known, again these boxes can be left blank. This design has purposefully been created to be flexible given that each case will be made up of different characteristics.

The financial motives for cybercrimes can be fraudulent and for financial gain however financial motivations can also relate to disruption of financial systems. Political motives link to the support or countering governmental policies or actions and can include state sponsored attacks, espionage and propaganda.

Moral motives can be associated with fighting for freedom, rights, and ethics, or against exploitation and oppression. Religious systems could fall into this category and are twofold: attacks by religious groups against other religious systems/beliefs; attacks toward religious groups against their belief systems/exploitation/religion as oppression. Moral motivations for cyber-attacks can be complex in nature—this taxonomy allows for general categorization and a limitation is that it could be seen as too simplistic.

Self-actualization relates to individuals or groups who carry out attacks out of curiosity—they could be testing their own knowledge and skill or testing the security systems—again for knowledge rather than for purposeful corruption or disruption. They may also hack for kudos or notoriety.

Whilst exploitation could fall in line with moral motivations it is a separate category which relates to the exploitation of human beings (for example, in cases of human trafficking and child abuse). Cases involving cyber bullying and/or cyber harassment could also fall under this category. In this chapter there is no case study which relates to this category however Chapter 11 discusses issues surrounding child exploitation.

The final motivation listed in this taxonomy is promotional which relates to publicity and for this taxonomy it means to gather awareness through news media, social media and in some cases develop and maintain an online presence. These definitions are not exhaustive but provide concepts for operators using the grid to create a repository.

In cases where cybercrimes have been conducted anonymously, it is difficult to categorize the agent's motivations unless they have released a statement to the press, or publicly laid claim to the attack outlining their reasons for conducting it. Whilst some hackers overtly state their reasons behind the attack, it is important to acknowledge that covert motivations may also be present but not publically acknowledged. This taxonomy works by being able to interchange the categories. The cyber-attack or crime may appear to have a primary motivation but then may also have a secondary motivation (which in some cases may be underlying). In more complicated contexts there may be multiple motivations where “tertiary” motivations can be applied. So for instance a DDoS attack on a bank may primarily be moral (against the fact the banking system is corrupt and has caused an economic crisis) but the secondary motivation may be publicity, whilst a tertiary may be self-actualization. Each case should be assessed individually and may even have multiple primary and secondary motivations.

Case Studies

The following case studies demonstrate each of the taxonomical motivations for conducting cybercrime. The Syrian Electronic army has “moral” motivates but is heavily driven by the need for publicity and is linked to the political motive category. This group of hackers claims to be conducting attacks in order to get their voices heard. The Stuxnet attack is linked to potential political motivation: to prevent the development of nuclear weapons. The attacks on the banking systems are linked to financial and moral motives whilst also linking to publicity. The Mafiaboy case relates to “self-actualization.” A case study for exploitation has not been included in this chapter but further information relating to exploitation can be found in Chapter 11.

Political/Publicity/Self-Actualization: The Case of the Syrian Electronic Army

The SEA were officially placed on the FBI's advisory list following a number of attacks in 2011. The FBI refers to the SEA as a “pro-regime hacker group” that emerged during Syrian anti-government protests in 2011 (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2013). Information accompanying the advice says that the SEAs primary capabilities are spearphizing; web defacement and hijacking social media with an aim of spreading propaganda.

Who Are They?

A team of eight people—thought to be young Syrians (five of whom had their own pseudonyms when their website was available to access)—who are in no way affiliated with any political party. They claim to have set up SEA in 2011 in response to Western and Arab media who they believe biasedly reported in favor of terrorist groups that have killed civilians, and are in favor of the Syrian Army. Currently, the group believes that they are protecting their homeland and strongly support the reforms of President Bashar-Al Assad.

Schneier (2013) speculates how much of an actual army the SEA are, and suggests that we do not actually know much about their age or whether they are even Syrian. What we do not definitely know is to what extent this group are backed by the Syrian government, so it is possible that the SEA are a group of amateur geo-Politian's.

In January 2014 their website was removed from Google Searches and their existing online profiles for twitter, Facebook and Instagram were removed although on 29th January 2014 they had re-set up accounts. Presumably this is something they will continually have to do if they are fighting against large-scale organizations like Microsoft (Hanley Frank, 2014).

The Facebook and twitter pages allow the group to publically lay claim to the attacks but also to voice their political viewpoints. They are particularly critical of organizations who deny users their rights to privacy.

Political or Moral Hackers?

It goes without saying that the more this group hacks and takes ownership for the hacking and phishing attacks, the more the media start covering stories about them and the more well-known they become. It is generally thought that they are not doing anything new or unusual in relation to the technical side of the attacks (basic phishing attacks and DOS attacks). However, these have been effective enough to cause inconvenience for companies such as Microsoft (who believes it is possible that their staff's social media accounts have been compromised—see Chapter 3).

It is clear from the closing down of SEAs social media sites and the re-opening of them hours later that this group understands the need to have an online social media presence in order to be a continued and renowned threat. On their current Facebook page they claim to be a Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) and three hours after re-instating a profile page they had 1600 “likes” whilst their twitter followers jumped from 10,000 in the first weeks of January to 12,500. They undoubtedly have some public backing although without conducting an analysis of the Facebook users who have liked the page and an analysis of their twitter followers it is difficult to categorically know who is backing them (see Chapter 10 for further discussion).

Before the SEA website (www.SEA.sy) was removed from Google searches it contained detailed information about the attacks they have instigated and also detailed why they had carried them out. They referred to hacks as achievements once again re-enforcing the argument that to be affective they need to hack high-profile organizations—and ensure that there is media coverage in order for them to re-enforce their notoriety—but also ensure their voice is being heard.

Methods: Phishing and DDoS

The media report on two main methods that the SEA makes use of: Phishing and DDoS attacks.

Phishing can involve sending out large numbers of e-mails, which contain a message that appears to originate from a legitimate source (i.e., a well-known company such as PayPal or Twitter). The aim of the e-mail is to convince the potential victim to provide their personal details. Some e-mails can direct readers to an external hoax website, which is made to look authentic. The website can also encourage the victim to provide their confidential information (bank account details, identifying details, social security numbers, passwords, etc.)—which can then be used by the Phisher to commit an array of subsequent fraudulent acts. Some more complicated phishing campaigns can include harmful malware in the email itself, or on the hoax website—which can directly extract the information it needs from the target's computer, without requiring the victim to provide the confidential information directly (see Chapter 12 for more detail about Phishing).

DDoS (Distributed Denial of Service) or a denial-of-service (DoS) usually involves a system being overwhelmed by simultaneous online requests. This can result in the service becoming unavailable to its users. Distributed denial of service attacks are sent by two or more people or bots whereas denial of service attacks are sent by one system or person (see Chapter 17 for further information).

Who Have They Hacked to Date?

The following information is a summary of the information available from media sources. The SEA have infiltrated the media across the world however it is not clear exactly how many attacks and who have been affected. The following are a number of examples which have occurred in 2013 and 2014.

Schneier claimed in August 2013 that the SEA had attacked the websites of the New York Times, Twitter, the Huffington Post amongst others although they had not done this directly but had gone through an Australian domain name called Melbourne IT. However, in January 2014, they made a number of “attacks” on the following organizations:

CNN

The SEA targeted the twitter and Facebook accounts of CNN. They laid claim to an attack on CNN (January 2014) advising on their twitter feed that

Tonight, the #SEA decided to retaliate against #CNN's viciously lying reporting aimed at prolonging the suffering in #Syria…#CNN used its usual formula of present unverifiable information as truth, adopting a report by Qataris against #Syria…Instead of any actual journalism, #CNN turned into a loud horn calling for the destruction of the #Syria-n state…US media strategy is now to hide the fact that the CIA controls and funds Al Qaeda by blaming #Syria instead for their terror #SEA…The #SEA will not stop to pursue these liars and will expose them and their methods for the world to see.

Given that their one of their main motivations is deemed to be political mobilization it is not surprising to see that the justification for the attack by SEA relates to the supposed misreporting about what is happening in Syria by CNN.

The SEA sent out five tweets before the CNN twitter feed was re-instated:

Syrian Electronics Army was here…Stop lying…All your reports are fake! via @Official_SEA16 #SEA

Long live #Syria via @Official_SEA16 #SEA ow.ly/i/4nt9l

Obama Bin Laden the lord of terror is brewing lies that the Syrian state controls Al Qaeda

For 3 years Al Qaeda has been destroyed the Syrian state but they think you're stupid enough to believe it

DON'T FORGET: Al Qaeda is Al CIA da. Funded, armed and controlled. (http://www.buzzfeed.com/michaelrusch/syrian-electronic-army-hacks-cnns-twitter-account)

Of course the content of these tweets can neither be confirmed nor denied: they are simply recorded for information. A CNN statement advised that the tweets were removed immediately and the affected accounts secured (Shoichet, 2014).

Angry Birds

In January 2014 the AngryBirds website was defaced. The angry birds logo was changed to “spying birds” with an NSA logo placed over one of the apps logos. This was thought to be carried out by a friend of SEA. Their twitter account said the following:

A friend hacked and defaced @Angrybirds website after reports confirms its spying on people. The attack was by “Anti-NSA” Hacker, He sent an email to our official email with the link of the hacked website.

The attack was in connection to a supposed NSA report which claimed that US and UK spy agencies (i.e., GCHQ) could access personal information—such as age and date of birth from the mobile app third-party advertising companies. Rovio (the app makers company) released a statement which said that they have not collaborated or colluded with any government spy agencies anywhere in the world (Rovio, 2014). Such a small defacement to a website by an outside source demonstrates a weakness in the sites security whilst also helping to publicize the supposed compromise of the personal data of its users.

Microsoft (January 2014)

January 2014 saw several attacks by the SEA on Microsoft. Reportedly through Phishing tactics the SEA gained access to employee social media and email accounts being impacted. They tweeted the following from @MSFTnews account: “Syrian Electronic Army Was Here via @Official_SEA16 #sea” which was removed quickly. Another tweet said: “Don't use Microsoft emails (hotmail, outlook), They are monitoring your accounts and selling the data to the governments #SEA @Official_SEA16.”

Berkman (2014) has reportedly contacted the SEA and received the following response when asked why they targeted Microsoft:

Microsoft is monitoring emails accounts and selling the data for the American intelligence and other governments.

And we will publish more details and documents that prove it.

Microsoft is not our enemy but what they are doing affected the SEA.

Saudi Arabian Government Websites (January 2014)

Neal (2014) reports that the SEA was also responsible for targeting the Saudi Arabian government website and seized control of a number of their domains. SEA were attacking in protest of the Al Saud regime which they believe makes use of a terrorist group. Their twitter feed once again allowed them to take credit and advertise their efforts. Each of the 16 principles of Saudi Arabia were mentioned individuality followed by a hashtag: #ActAgainstSaudiArabiaTerrorism #SaudiArabia. It is worth noting that there is less media coverage about this incident than other attacks on large companies (see Chapter 13 for further information).

Social Media Presence

Given that they are aware of their need for social media presence members of the SEA have reportedly spoken to a number of press sources. However one interview in particular was tweeted via a link refers to a text-based conversation that they had with Matthew Keys in December 2013. In their exchange they advise that they are students and highlight that SEA chooses its targets based on media reporting bias—they particularly refer to a times article which they believe reports on only one side, i.e., against Bashar Assad. In the interview they highlight that they do not trust media in general but particularly that some media are not agenda driven when it comes to Syria. They also believe that their identities must be kept unknown or they will be subject to threats from the US. In the interview they stress that they are only doing what they do to ensure that the media report the truth to the world after witnessing terrorist attacks on their countries police. It is difficult to know definitively how much of what they say in the interview is propaganda and how much is truth. Ultimately the SEA advise that they want to stop the fourth generation war on their country but their counter message is that they want to reveal the real hand behind terrorism. They also categorically deny any ties to the Syrian, Russian or Iranian governments. The full interview transcript can be accessed at http://thedesk.matthewkeys.net/2013/12/11/a-live-conversation-with-the-syrian-electronic-army/ (Keys, 2013) (see Chapter 15 for further detail about social media).

Masi (2013a) claimed to speak to a SEA member named “Richie” in September 2013 but she herself admits that there is no way of confirming this. The transcript reiterates similar main messages from the Key's interview in December 2013: “Hacking will drive attention, opinions and a well delivered message to whatever the issue is.” In a second interview with a SEA leader Masi (2013b) highlights the possibility that some of the media presence is being conducted by others who claim to be SEA but are not.

The SEA claim to not be linked to the Syrian government however some of their attacks have been to an extent politically motivated. For the purposes of this taxonomy the cases listed could primarily fall under the “moral” category—and the SEA often make public statements about why they are carrying out their acts—linking their actions to ethical causes. However, the fact that they heavily rely on social media and lay claim to attacks that occur globally leads to a secondary motivation as potentially being publicity. Some of their actions could also be linked to self-actualization.

The Case of Stuxnet

In June 2010, a computer virus Stuxnet was believed to be created to attack Iran's nuclear facilities. It is widely speculated by media sources that the United States and Israel collaborated to facilitate this attack although it has never been officially confirmed by either country. This is the first case of publicly known intent of cyber warfare. A NATO research team in 2013 agreed that the Stuxnet attack on Iran was an “act of force” (Schmitt, 2013). The virus included a special malware that specifically monitors industrial systems whilst doing little harm to computers and networks that do not meet its configuration requirements. It is thought that it was designed to destroy nuclear plant machinery and as a result slow or halt the production of Low Enriched Uranium.

It is believed that different variations of the virus targeted five Iranian organizations including the Natanz nuclear facility (Zetter, 2010). Security specialists (Kaspersky, Sysmantic, Cherry, 2010; Langner, 2011) believe that due to the complexity of the virus implementation and its sophisticated nature, it was more than likely conducted with “nation state support.” UK and US media sources (The Guardian, the BBC and The New York Times) also claimed that (unnamed) experts studying Stuxnet believe that only a nation-state would have the capabilities to produce it due to the complexity of the code (Halliday, 2010; Markoff, 2010; Fildes, 2010).

Borg (2010) of the United States Cyber-Consequences Unit stated,

Israel certainly has the ability to create Stuxnet and there is little downside to such an attack, because it would be virtually impossible to prove who did it. So a tool like Stuxnet is Israel's obvious weapon of choice.

To date, Israel has not publicly commented on the Stuxnet attack but has confirmed that cyber warfare is now at the forefront of their defense doctrine, with a military intelligence unit set up specifically to pursue both cyber-related defensive and offensive options (Williams, 2009). American officials have indicated that the virus originated abroad.

Either way the nature of cyberspace means that it is challenging to find out exactly who is responsible for the activities conducted, the actions taken, and the origin of an activity. It is especially difficult to prove who is behind Stuxnet. Although it does seem that Stuxnet was designed to be destructive and is the first attack of its kind. Given the facts available about this incidence, it would more than likely fall under the political category although it could fall under moral or financial categories if further information surrounding the attack was made public (Chapters 3 and 13 also make use of this example).

The Cyber-Attacks on Banks

On a Global Scale

Operation High Roller consisted of a series of fraud activities targeted at the banking system across the world. It made use of multifaceted automation to collect data in order to raid bank accounts including commercial accounts and institutions of all sizes. This sophisticated method for data collection allowed the operation to run faster. A review in 2012 of the operation led McAfee and Guardian Analytics found that nearly $78 million was removed from bank accounts due to this attack. The operations servers were based in Russia, Albania and China, but the attacks started in Europe, moved to Latin America and then targeted the US. Whilst there are no concrete figures for how much cybercrimes cost the world economy estimated figures range from $100 to $500 billion per year.

In the UK

In November 2013 the Bank of England released a financial stability report which detailed a number of attacks across the UK banking sector—the report states:

Cyber attack has continued to threaten to disrupt the financial system. In the past six months, several UK banks and financial market infrastructures have experienced cyber attacks, some of which have disrupted services.

(Bank of England, 2013, p. 25)

The report also accepts that the banking sector is susceptible to cyber-attacks as it has a “high degree of interconnectedness, its reliance on centralised market infrastructure and its sometimes complex legacy IT systems” (Bank of England, 2013, p. 54).

The “systemic” threat to the UK banking and payments system is recognized in the report: “While losses have been small relative to UK banks' operational risk capital requirements, they have revealed vulnerabilities. If these vulnerabilities were exploited to disrupt services, then the cost to the financial system could be significant and borne by a large number of institutions” (p. 25).

The report was published as the UK banks took part in a one day cyber threat exercise called Operation Waking shark II which aimed to test the financial systems ability to withstand major cyber-attacks. These types of operations require competitors across the sector to share information about the potential threats and this type of co-operation is not yet believed to be present.

In December 2013 Natwest and Royal Bank of Scotland, UK-based banks were subject to a number of DDoS attacks which reportedly cost them millions in compensation. The DDoS impacted on the bank's websites and directly affected the bank's customer's ability to use their services. Currently, there is no conclusive information about who was responsible for the attack or motivation for the attack. Had a notorious hacking group been behind the attack they would more than likely to have laid claim to it (Tadeo, 2013).

In October 2012, a group of hacktivists did lay claim to the DDoS attack on HSBC which impacted millions of user's ability to access their online accounts around the world. Following these kinds of attacks it is commonplace to see banks defending customer data—usually insisting that the attacks did not compromise personal information. A hacking group who call themselves fawkes security on Twitter and who act in association with the “Anonymous” ideology (see section below) laid claim to the DDoS attack on HSBC their justification being that the banks are corrupt and have caused the global economic crisis. The group tweeted counter information suggesting that personal data were affected:

When HSBC said “user data had not been compromised” This isn't entirely correct. We also managed to log 20,000 debit card details. #OpHSBC

There is no evidence to back these claims. There is also no evidence to suggest that it was related to fraudulent activity. Although DDoS attacks can be used in conjunction with takeovers of bank's systems to commit fraud or steal intellectual property.

Disruptive DDoS attacks are becoming larger with volumetric flooding of servers with jumbled or incomplete data. Meaning there is an increasing need to gather and share intelligence and strategies amongst networks and across the financial sector in relation to attacks of this nature (Ashford, 2013; Rashid, 2013).

Whilst the context for this case study is financial—the primary motivation may not fall under “financial” as the Anonymous attack on HSBC demonstrates and thus could fall into the “moral” category. However, publicity could also motivate the attacks for notorious groups. DDoS attacks are usually highly disruptive and can be used to mask other fraudulent activities—in these cases then “financial” would be the primary motivation.

The Case of the Anonymous Attacks on Scientology

Anonymous is an international network of activists who originated on an image-based bulletin board (B) 4Chan in 2003. Over the past ten years they have become known for a large number of DDoS attacks on corporate, government, religious websites. Anonymous (Anonymous, 2014a) describe themselves as “a decentralized network of individuals focused on promoting access to information, free speech, and transparency” (http:www.anonanalytics.com). According to Kelly (2009) “even under the discrete umbrella of hacktivism, however, Anonymous has a distinct make-up: a decentralized (almost non-existent) structure, unabashed moralistic/political motivations, and a proclivity to couple online cyberattacks with offline protests” (p. 1668). A website associated with the group describes it as “an internet gathering” with “a very loose and decentralized command structure that operates on ideas rather than directives” (http://anonnews.org/static/faq) (Anonymous, 2014b).

Internet censorship and control is at the heart of the group's philosophy and they have orchestrated a number of well publicized stunts. This case study will focus on Project Chanology—a protest against the practices of the Church of Scientology (2008).

Project Chanology started after the Church of Scientology tried to remove a mock-up of an interview conducted by Tom Cruise talking about Scientology from Youtube. Anonymous stated that they believed that the Church of Scientology were committing acts of Internet Censorship and started a number of DDoS attacks which were followed by a series of prank calls designed to cause the Church of Scientology as much disruption as possible.

Following the DDOs attacks, in February 2008 people across the world who associated themselves with the Anonymous philosophy took direct action by protesting against the church on the streets. It is estimated that about 7,000 people protested in at least 100 cities worldwide—with thousands of photos of the events uploaded onto websites like flickr. Further protests were carried out in March and then April 2008.

The DDoS attacks impacted on the Church of Scientology's website which went down on a number of occasions in late January (Kaplan, 2008; Vamosi, 2008). As a result the scientology.org website was moved to a safeguarding company to prevent further DDoS, however the attacks against the site increased and consequently was once again inaccessible (Kaplan, 2008). Anonymous in a press release and video declared “war on scientology” advising that it would continue its attacks in order to protect freedom of speech (see Youtube Anonymous 2008 Message to Scientology).

Whilst this case could fall under the categorization of “religion” the underlying reasons for the attacks are much more complicated. Whilst publicity does play a part in the campaign, claims relating to morals are a key justification for the attacks. This case is also interesting because it is not restricted to online attacks but also direct action. Ethical hacktivists such as Anonymous maintain that they are fighting for the moral high ground aiming to seek quality of life for others as well as world improvement.

Self-Actualization: The Case of “Mafiaboy”

Michael Calce (Mafiaboy) was a 15-year-old Canadian school student when he carried out a series of DDoS attack on several major corporations including Yahoo, eBay, CNN, Dell and Amazon in 2000. Calce started by targeting Yahoo in an operation he called Project Rivolta (meaning Riot in Italian) his goal being to establish dominance for himself and TNT, his cyber group (Calce, 2008).

Genosko (2006) said of the case:

He wasn’t a programmer. He acquired an automated “rootkit” written by somebody else and then set it to work “anonymously.” Mafiaboy executed a Distributed Denial of Service Attack (DDoS) – a “flood” of messages (packets) that by volume alone disabled servers unable to cope with the demands placed upon them – with borrowed script, in this case, a denial-of-service program authored by “Sinkhole” (although early press reports fingered a creation by a “mixter” called Tribal Flood Network). He planted a number of DOS agents on “zombies” – hijacked computer systems at universities, and remote-controlled the operation with his automated software, using the captured computers to inundate selected Web sites with data packets (numbered chunks of files).

This was a groundbreaking case of cybercrime at the time and proved that internet security needed to be drastically improved given that the largest website in the world (Yahoo in 2000) could be shut down by a 15-year-old. The hacks provided evidence that there were major holes in internet security and this was used as a part of his argument for defense: he wanted to expose such faults and become a computer security specialist.

Calce admitted that he committed the attacks out of curiosity. “At that point in time, everyone was running tests and seeing what they could do and what they could infiltrate” (Infosecurity, 2013). Whether this was motivated by self-actualization, curiosity or a method for testing weaknesses in security systems, Calce' DDoS attacks are thought to have costs companies in excess of $1 billion (CAD) according to various media sources (Niccolai, 2000).

Strategic Responses to Cyber Attacks

Having explored the different cyber cases above it is also important to highlight that different countries use different strategies for dealing with these attacks. Below is a brief overview of the UK, USA's, and EUs strategies for dealing with cybercrime.

The Comprehensive National Cyber security Initiative set up by the US government in 2008 consists of the following goals which are designed to help secure the US:

• To establish a front line of defense against today's immediate threats

• To defend against the full spectrum of threats

• To strengthen the future cyber security environment

The document also lists 12 key initiatives:

• Manage the Federal Enterprise Network as a single network enterprise with trusted internet connections

• Deploy an intrusion detection system of sensors across the Federal enterprise

• Pursue deployment of intrusion prevention systems across the Federal enterprise

• Co-ordinate and redirect research and development (R&D) efforts.

• Connect current cyber ops centers to enhance situational awareness

• Develop and implement a government-wide cyber counterintelligence (CI) plan

• Increase the security of our classified networks

• Expand cyber education

• Define and develop enduring “leap-ahead” technology, strategies, and programs

• Define and develop enduring deterrence strategies and programs

• Develop a multi-pronged approach for global supply chain risk management

• Define the Federal role for extending cyber security into critical infrastructure domains (The White House, 2009).

The Department of Defense Strategy for Operating in Cybercrime (2011) has Five Strategic Initiatives:

1. Treat cyberspace as an operational domain to organize, train, and equip so that DoD can take full advantage of cyberspace’s potential

2. Employ new defense operating concepts to protect DoD networks and systems

3. Partner with other U.S. government departments and agencies and the private sector to enable a whole-of-government cybersecurity strategy

4. Build robust relationships with U.S. allies and international partners to strengthen collective cybersecurity

5. Leverage the nation’s ingenuity through an exceptional cyber workforce and rapid technological innovation

The UKs Cyber Security Strategy (2011) consists of four main objectives:

• Tackling cyber-crime and making the UK one of the most secure places in the world to do business in cyberspace.

• Making the UK more resilient to cyber-attack and better able to protect our interests in cyberspace.

• Helping to shape an open, vibrant and stable cyberspace which the UK public can use safely and that supports open societies.

• Building the UKs cross-cutting knowledge, skills and capability to underpin all our cyber security objectives.

The UK strategy involves focusing on individuals and businesses. The UK strategy admits that the threats are changing but details the following as being current threats in cyberspace:

• Criminals (fraud/identity theft)

• Other States (espionage/propaganda)

• Terrorists (propaganda/radicalize potential supporters/communicate/plan)

• Hacktivists (disruption/reputation management/financial damage/gaining publicity)

The UK strategy also highlights the difficulty in targeting the perpetrators of cybercrimes: “But with the borderless and anonymous nature of the internet, precise attribution is often difficult and the distinction between adversaries is increasingly blurred” (2011, p. 16).

The EU Cybersecurity-Strategy of the Europe Union: An Open, Safe and Secure Cyberspace (2013) understandably considers the concerns of a number of countries as opposed to one, and therefore stresses the borderless multi-layered nature of the internet. It has five key strategic priorities:

• Drastically reducing cybercrime

• Developing cyberdefence policy and capabilities related to the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP)

• Develop the industrial and technological resources for cybersecurity

• Establish a coherent international cyberspace policy for the European Union and promote core EU values.

The different strategies highlight a need for a strong global network of shared intelligence and communication about cybercrimes. The networks are not only the responsibility of governments and experts but also industry and the wider society. Strong partnerships, along with shared knowledge and information could strengthen the plight against cybercrime and attacks which cost the global economy billions each year (McAfee, 2013).

There are three different strategies for managing cybercrime presented above; however there are many more initiatives globally (for example see Australia's 2009 or see Canada's 2010 strategy). To create a strategy which extends across many different domains, the appropriate knowledge can be extracted from these strategies (and others), and used to recommend an increasingly consolidated viewpoint. The applicable gaps and overlaps would help to provide efficient and integrated solutions (be they regulatory, technical, ethical, legal or societal) to existing threats and could also help to anticipate (and therefore prevent) future ones.

Concluding Remarks

This chapter has reviewed a number of examples of cyber-attacks. Based on different legal and political jurisdictions they may constitute as a criminal offence. For example in the case of the SEA conducting “hacktivism” is claimed to be a method for making the voices of people who would not normally have a voice, be heard. Carrying out phishing attacks and DDoS for this group seems to be a form of political mobilization but in many instances—government websites are not at the forefront of these attacks—businesses are. It drums up publicity for their cause—whilst highlighting that there are security breaches in even in the largest organizations that are supposed to be leaders of security—thus increasing their notoriety. Without condoning or condemning their actions, this seems to be a simple way of causing disruption for companies—and is one which replaces protesting on the streets. Key to their voice being heard is the fact that they know there is a need for them to have a social media presence—to the point where they have to create a new social media pages sometimes daily. With a constant social presence and continued phishing attacks and DDOS attacks aimed at various outlets they manage to create not just a social media presence but a presence in the media and, consequently, to some extent an awareness of their cause. On the other hand, the SEA may be targeting nonpolitical websites because they are vulnerable opportunities and may be claiming moral significance to obtain publicity. Either way it is slightly incongruous that they claim to not trust media in general but make use of it for their own means.

Stuxnet is thought to be the first case of publicly known cyber warfare and whilst it is politically driven, it may also have moral and financial motives. The case is shrouded in speculation—experts have guessed that it was the work of a nation state and if there was hard evidence to support these assertions this case would be categorized as political. Whilst legally it remains unclear who carried out the attack, moral motivates can be applied (in relation to the point of the attack: to disrupt the production of nuclear outputs) whilst also disrupting the finances of the country through damaging industrial systems.

Operation High Roller directly points to financial motivations since fraud activities were committed during the attacks. Whilst DDoS attacks disrupt banking services they can also cover up fraudulent activity, and can be classed as financial, they can also be classed as moral since hackers also claim that banks are corrupt. The threat here remains with the banking sector but can have a direct impact upon individuals.

In cases where self-actualization occurs—i.e. the hackers attack to test systems or do it because they can—like in the Mafiaboy case—the threat can be classed as high impact.

Operationally, to start making assessments about threats, a method for collecting information and data using a taxonomy system for situational understanding has been presented. This model focuses on the intent and motivation behind cybercrimes and rather than taking a technical approach focuses on human factors. The five real-life cases not only show the diversity and sometimes complexity of individual crimes but also show the difference in motivations for the crimes. The proposed taxonomy for creating a knowledge repository therefore particularly focuses on the perceived motivations and intent of potential suspects and perpetrators. Using the taxonomy model above provides a starting point toward gaining a clearer situational understanding of cybercrimes. Currently with a number of cybercrime strategies across the globe, and with no agreed definitions or legislation—gathering knowledge about the cybercrimes—including situational knowledge will help to foster the practical implications for countermeasures. This is especially true when considering our earlier definition of knowledge. Given the lack of agreed definitions and numerous strategies for cybercrime, the model has been designed to be flexible for front line officers especially in light of the fact that cases vary in nature. The model also makes use of simple language since a Universal linguistic system for cybercrime has not yet been agreed.