ICT as a protection tool against child exploitation

Mohammed Dastbaz; Edward Halpin

Abstract

This chapter explores the impact of emerging technologies and how it can be used to develop a better ICT protection tool for child protection. The chapter looks at the key issues and challenges facing governments, child care organizations and parents specifically: Information and awareness about the issues; Legal framework and difficulties dealing with cross border issues and globally agreed methods of working; Technical challenges (information flow, access and processing). A case study approach is presented that investigates the development and delivery of a Missing Child Alert program, an initiative instigated and led by Plan International. Furthermore, the feasibility of developing a technology-enabled system that would act as a digital alert system providing support for relevant government and nongovernment agencies dealing with Child Trafficking in South East Asia is presented. As significantly the cultural, social, political contexts need to inform development, especially when working with complex human systems and transnational development of technology, which require political decisions.

Introduction

Albert Einstein is quoted as saying: “It has become appallingly obvious that our technology has exceeded our humanity.” Indeed 2013 has been a year of significant revelations about the dominance of Information Communication Technologies in our lives. The dominance of mobile communication technologies, the 24/7 constantly connected lives we live in, and the shifting patterns of how we socialize, shop, learn, entertain, communicate or indeed how we diet and are ever more conscious about our health and wellbeing, points to what some would like to term the “third industrial revolution” (Rifkin, 2011).

The phenomenal advance of technology has meant concepts such as privacy and private information, for those billions of people who have ventured into the web of technology is nothing but a mirage. Revelations about security agencies around the world monitoring every digital move we make (from text messaging to our tweets, Facebook conversations and even our shopping patterns) has confirmed that as individuals we have no right, and indeed very little if any protection, against these unwanted and unwarranted intrusions. The Guardian (16 January 2014) reported that: “The National Security Agency has collected almost 200 million text messages a day from across the globe, using them to extract data including location, contact networks and credit card details, according to top-secret documents….”

Another growing concern in recent years has been issues around children’s safety on the global digital network. From “Cyber bullying” to children being exposed to violence and pornography, to the “net” being used as a channel for trafficking children and other criminal activities, there is growing concern and challenges around how we can provide a safe digital environment for children.

A report published by “Childhood Wellbeing Research Centre” in UK in 2011 stated that: “Ninety-nine percent of children 12-15 use the internet as 93% of 8-11 years old and 75% of 5-7 years old” (Munro, 2011).

The report further highlights that a US survey reported 42% of young people age 10-17 being exposed to on-line pornography in a one-year period and 66% of this was unwanted.

In a report by “E-Crime,” The House of Commons Home Affair Committee we read: “We are deeply concerned that it is still too easy for people to access inappropriate online content, particularly indecent images of children… There is no excuse for complacency. We urge those responsible to take stronger action to remove such content. We reiterate our recommendation that the Government should draw up a mandatory code of conduct with internet companies to remove material which breaches acceptable behavioural standards… [it is] important that children learn about staying safe online as it is that they learn about crossing the road safely” (E-Crime House of Commons, 2013).

While there is much to do to develop the legal framework around what can be blocked, or not, and to put the necessary technologies in place, the Web itself is rapidly developing and new technological challenges emerge. Time magazine (November 2013) produced a special report about what has been termed as the “Deep Web.” Like the story of the Internet the story of the “Deep Web” is also associated with the US military and research done by scientist associated with the US Naval Research Laboratory aimed at “Hiding Routing Information.” The report states that what was being developed: “laid out the technical features of a system whereby users could access the Internet without divulging their identities to any Web server or routers they might interact with along the way.”

The “Deep Web” as the report worryingly suggests is where organized crime or terror networks work with masked identities and it is also where drugs, false passports, sophisticated SPAM, child prosopography and other criminal activities are organized with untraceable currency like “Bitcoin” (also see Chapter 9).

So given the complexity of the legal frame work and the ever increasing technical challenges what are the key issues that we need to tackle not only to provide a safer digital world for the children but also use the technology itself to help us develop the solutions.

Key Issues and Challenges

The key issues and challenges facing governments, child care organizations and parents alike can be broadly categorized into the following:

• Information and awareness about the issues

• Legal framework and difficulties dealing with cross border issues and globally agreed methods of working

• Technical challenges (information flow, access and processing)

It is perhaps worth considering what the overarching legal framework, applied to all countries, provides for when considering children, in relation to these key issues. The United Nations Conventions on the Rights of the Child (CRC) (UN, 1989), amongst other clauses provides the following:

• Article 3—on the best interests of the child—states that in all circumstances concerning the child, they should be the primary focus, whether this is within public or private institutions, legal or administrative settings. In each and every circumstance, in each and every decision affecting the child, the various possible solutions must be considered and due weight given to the child’s best interests. “Best interests of the child” means that the legislative bodies must consider whether laws being adopted or amended will benefit children in the best possible way.

• Article 16 (Right to privacy): Children have a right to privacy. The law should protect them from attacks against their way of life, their good name, their families and their homes. 5 Article 17 (Access to information; mass media): Children have the right to get information that is important to their health and well-being. Governments should encourage mass media—radio, television, newspapers and internet content sources—to provide information that children can understand and to not promote materials that could harm children. Mass media should particularly be encouraged to supply information in languages that minority and indigenous children can understand. Children should also have access to children’s books.

Hick and Halpin (2001), in considering the issue of children, child rights, and the advances of “Child Rights and the Internet” make the point that rights are balanced and not absolute and that technological advances will continue bringing the same need to review and reflect change to protect children and ensure that they benefit from technology.

Information Awareness and Better Education

The extant literature points to the fact that lack of awareness and useful information around the risks involved as well as privacy and the implications of our behavior quite often leads to increased risk specially when it comes to children and teenagers. In a research carried out by Innocenti Research Centre (IRC) and published by UNICEF titled: “Child Safety Online Global challenges and strategies,” in 2011 serious concerns are raised about lack of understanding of issues and risk associated with children using the Internet and making information about themselves so publically available. The report goes on to state:

Concern is often expressed among adults about the risks associated with posting information and images online. Hence, much research starts from the premise that posting information is in itself risk-taking behaviour. Young people are indeed posting information that adults may find disturbing. A wealth of evidence from across the globe shows that many young people, particularly in the age range of 12 to 16 years, are placing highly personal information online. In Brazil, for example, surveys indicate that 46 per cent of children and adolescents consider it normal to regularly publish personal photos online, while a study in Bahrain indicates that children commonly place personal information online, with little understanding of the concept of privacy.

The report further notes that:

In addition, significant numbers of teenagers are uploading visual representations of themselves that are sexual in tone. This is sometimes in response to grooming that involves encouragement to place such images online, which may be followed by blackmail or threats of exposure to coerce teenagers to upload increasing numbers of explicit images. But in other cases, the initial placement is unsolicited, and may encourage and attract potentially abusive predators.

Clearly while the reach and use of social network grows and posting highly personalized information is viewed as “normal” there needs to be much better education as well as a more responsible social network protocols governing children use.

Government Responsibilities and Legal Framework

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), in a report published in May 2011, acknowledges that the legal and policy framework for protecting children in the global digital network is extremely hazardous and complex. The complex policy challenges include: how to mitigate risks without reducing the opportunities and benefits for children online; how to prevent risks while preserving fundamental values for all Internet users; how to ensure that policies are proportionate to the problem and do not unsettle the framework conditions that have enabled the Internet economy to flourish?

Furthermore, governments have tended to tackle online-related sexual exploitation and abuse with an emphasis on building the “architecture” to protect or rescue children—establishing legislation, pursuing and prosecuting abusers, raising awareness, reducing access to harm and supporting children to recover from abuse or exploitation. These are essential components of a protection response.

It is also worth noting that despite various efforts we are far from a globally agreed set of guidelines and legal framework that protects children from serious risks they face on-line. Clearly this is a serious gap exploited by criminals and those who have vested interest in using the current “freedoms” for personal monitory benefit.

Technical Issues and Challenges

A Case Study on Use of Technology and Proposed Methodology

In a research conducted by Lannon and Halpin (2013), to investigate the development and delivery of a Missing Child Alert (MCA) program, an initiative instigated and led by Plan International (referred to as Plan) in 2012, the feasibility of developing a technology-enabled system that would act as a digital alert system providing support for relevant government and nongovernment agencies dealing with Child Trafficking in South East Asia was explored (Lannon and Halpin, 2013).

One of the key issues and challenges for the research was how we classify missing children. Children go missing for many reasons. In South Asia, many are abducted and put into forced labor. Others are persuaded to leave home by somebody they know, and are subsequently exploited in the sex trade or sold to work as domestic help. Some simply run away from home, or are forced to leave because of difficult circumstances such as domestic violence or the death of a parent.

The issue of missing children is also linked to, although not limited to, child trafficking. This is a highly secretive and clandestine trade, with root causes that are varied and often complex. Poverty is a major contributor but the phenomenon is also linked to a range of other “push” (supply side) and “pull” (demand side) factors. The push factors include poor socio-economic conditions; structural discrimination based on class, caste and gender; domestic violence; migration; illiteracy; natural disasters such as floods; and enhanced vulnerability due to lack of awareness. The pull factors include the effects of the free market economy, and in particular economic reforms that generate a demand for cheap labor; urbanization; and a demand for young girls for sexual exploitation and marriage. Trafficking is a complex phenomenon, but many of the children end up in the leisure industry that could include pornography, with an international market via technology.

A UNICEF report in 2008 noted that there is a lack of synergy and coordination between and among the action plans and the many actors involved in anti-trafficking initiatives in the region, including governments, UN agencies and NGOs. According to the report the diversity of their mandates and approaches makes coordination at national and international levels a challenge.

Attempts to address cross-border child trafficking have proved to be particularly problematic because of a lack of common definitions and understandings, and the existence of different perspectives on the issue. For a start there is no commonly agreed definition of trafficking (UNODC, 2011). Furthermore, the definition of a “child” can vary as has been noted already. This has an impact on how the police, courts and other stakeholders address a child’s rights, needs, vulnerability and decision making.

Child trafficking is often seen in the context of labor or sexual exploitation, with the latter focusing primarily on women and girls, but increasingly can include boys. In some cases it is approached as a migration issue or as a sub-category of human trafficking. Furthermore, authorities often see it as a law enforcement issue, and their responses are thus primarily focused on criminal prosecution and tighter border controls.

Worldwide, the most widely accepted definition of trafficking is the one provided by the UN Protocol on Trafficking (Palermo Protocol). It defines “trafficking in persons” as

the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation.

As the UNODC (2011) report notes, domestic laws in the South Asia region lack a shared understanding of trafficking. The most commonly applied definition is the one adopted by the SAARC Trafficking Convention which, as was noted already, is limited to trafficking for sexual exploitation. Nonetheless, it is important to have a common understanding between governments and other MCA stakeholders in order to ensure the effectiveness of cooperation efforts and the development of future policy.

A “missing child” is generally understood to be a person under the age of 18 years whose whereabouts are unknown. This definition encapsulates a range of sub-categories of missing children. The International Centre for Missing & Exploited Children (ICMEC) has identified a number of these, including but not limited to: “Endangered Runaway,” “Family Abduction,” “Non-family Abduction,” Lost, Injured, or otherwise missing and “Abandoned or Unaccompanied Minor.”

The ICMEC highlight the importance of understanding what is meant by a missing child:

A common definition of a ‘missing child’ with clear categories facilitates coordination and communication across jurisdictions and ensures that policies and programs comprehensively address all aspects of missing children’s issues. Although all missing child cases should receive immediate attention, investigative procedures following the initial report may vary based on the case circumstances.

Already a large body of knowledge exists in relation to the recording and alerting of missing children. At a regional level there are a myriad of formats in use to describing a missing child. Getting agreement on a shared, comprehensive data model, with coded typologies to describe the status of a missing child, the physical identification markings on him or her, etc. will ensure coherence and consistency of information and will facilitate faster searching across systems. This data model should also support the use of noncoded data, and in particular photographic and biometric data.

The use of coded typologies will ensure that the recording of missing and found children is consistent across all languages, and that matches can be found between records entered in different languages.

The MCA program should take a proactive role in efforts to develop coded typologies or thesauri to support consistent and standard reporting of missing children in South Asia, in line with child protection norms and best practice. This should be done in collaboration with ICMEC who are already working in a number of related research areas.

Objectivity, Consistency and Credibility

Furthermore, in order to produce meaningful statistics a controlled vocabulary is a fundamental requirement. It transforms the data relating to child trafficking cases into a countable set of categories without discarding important information and without misrepresenting the collected information.

The development of a standard data model should be the basis for the design of any technologically enabled information systems implemented as part of the MCA initiative.

A Systems Approach to Child Protection

A system is a collection of components or parts organized around a common purpose or goal. As the MCA’s goal is improved protection of children from trafficking and exploitation it can be described as a child protection system. System components can be best understood in the context of relationships with each other rather than in isolation. Several key elements of systems apply to child protection systems (Wulczyn et al., 2010). These include the following:

• Systems exist within other larger systems, in a nested structure. Children are embedded in families or kin, which live in communities, which exist within a wider societal system.

• Given the nested nature of systems, attention needs to be paid to coordinating the interaction of related systems so that their work is mutually reinforcing.

• Systems accomplish their work through a specific set of structures and capacities, the characteristics of which are determined by the context in which the system operates. In the case of cross-border child trafficking, the context varies between countries, government departments and in some cases even interventions.

• Changes to any system can potentially change the context, while changes to the context will change the system.

• Well-functioning systems pay particular attention to nurturing and sustaining acts of cooperation, coordination and collaboration among all levels of stakeholders.

• Systems achieve their desired outcomes when they design, implement, and sustain an effective and efficient process of care in which stakeholders are held accountable for both their individual performance and the performance of the overall system.

• Effective governance structures in any system must be flexible and robust in order to cope with uncertainty, change, and diversity.

The adoption of a systems approach means that the challenges presented by the MCA initiative are addressed holistically. The roles and assets of all the key actors, including governments, NGOs, community structures, families and caregivers, technology providers, and most importantly children themselves, are all taken into consideration.

Child-Centered Information Flows

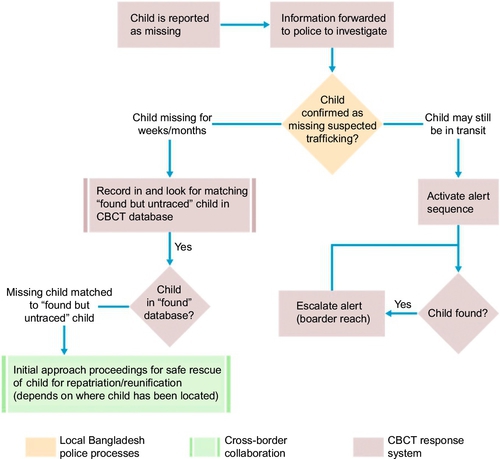

A holistic approach to child protection dictates that a cross-border child Information Management and Child Protection trafficking response system should support the full range of activities triggered by the reporting of a missing child who is presumed to have been trafficked. Taking an event-based approach favored by human rights organizations, a series of high level events can be identified. These include but are not limited to: child is reported as missing; child is recovered; child’s body has been found; child is referred for rehabilitation; child is safely integrated into a new environment in the country in which (s) he was rescued; repatriation process has been initiated; repatriation has been completed/process of reintegration has be set in train; and child is safely reintegrated into their family and community.

Each event triggers a set of child-centered actions and information flows that can be configured based on the details of the event and the context in which the event is occurring. Figure 11.1 describes the information flow that should take place in the source country for the first event in the process, which is that a child is reported as missing. It shows a series of six fundamental actions that should occur as follows:

Intake of initial missing child report. This occurs when a family member approaches the police or other agency to report a missing child.

The analysis and verification of information relating to a missing child should be done by police in the source country, whereas the recording of a trafficked child, the sending of alert messages, and the subsequent analysis of data and generation of periodic reports can be handled by a regional cross-border response system. The processes of reporting and alerting could be implemented as one technological system with distinct functionality and user roles.

The functionality and user interfaces of the systems for reporting, recording and alerting must be done through discussion with key stakeholders, particularly the police who will record and initiate alerts for a missing child. While this will inevitably slow down the deployment process, failure to do so may result in a system that is not accepted by the authorities upon whom its success depends.

This means that State support for the concept and their involvement from the start are essential as well as NGOs along the likely transit routes. It must also schedule follow-up alerts if the child has not been found/rescued after a period of time. The configuration of the alerting schedule is a vital component of the system which requires expert understanding of.

One point that requires further discussion with stakeholders is the question of alerting for children who are reported as missing and may have been trafficked or abducted internally within the country. These cases could be handled by internal police systems. Alternatively, the cross-border response system could be designed to support responses to internal trafficking.

The proposed CBCT (Centralized Cross-Border Child Traffic) response system should limit its activities to those that require cross-border communication and collaboration. This means it should support information flows relating to trafficked children that may have been taken across a border, found children whose identity is not known (resulting in a search of existing databases, including the CBCT response database), and rescued children whose needs may be best addressed through repatriation and reunification. How the traffickers behave and their routes. Furthermore, it will benefit from a proactive approach whereby alert recipients are identified along with the most appropriate means of alerting them. A controlled database of alert recipients should be managed in support of this work.

It is widely accepted that the first hours after a child has been taken to provide the best opportunities for rescue. It is therefore vital that alert notifications are sent as quickly as possible to the authorities and NGOs along the likely trafficking route taken. However, the advantage of immediate alerting must be balanced with the need to ensure the veracity of a missing child report. Even more importantly, a decision to send an alert notification needs to take into account the safety, well-being, and dignity of the child. A basic principle adopted in missing child alert systems around the world is that there must be sufficient information for the recipients to be able to respond to an alert. While much of the alerting can be automated, the preceding activities can be assisted by technology but are primarily human-based. The decision-making process leading to the issuing of an alert must be clearly defined and understood. Many MCA stakeholders are of the view that a system to coordinate all activities relating to the rescue, rehabilitation, repatriation, and reintegration of victims of cross-border trafficking would be helpful. The research goes on to propose that the MCA would have a role in actively supporting prosecution. While these are all desirable, it is overly ambitious and unnecessary to try to coordinate all these activities in one technological system or database. Instead, in-country (national) systems need to be strengthened to address areas like child welfare and justice. Each case recorded in the cross-border response system should remain open until the child’s rights and needs are known to have been fully met. This can take many years and may span a series of interventions including shelter home (Figure 11.2).

The report draws a conclusion that indicates the requirement for a technological solution, and provides a strategy for delivering this, but reiterates the complex social, economic, legal, and political setting in which such technology needs to, and will be, deployed.

This recognition leads us back to the three key issues identified at the outset.

• Information and awareness about the issues

• Legal framework and difficulties dealing with cross border issues and globally agreed methods of working

• Technical challenges (information flow, access and processing)

CBCT Response System

One of the options considered by the research was a centralized CBCT response system dedicated to addressing the needs of children who have been trafficked across a border. For this, a regional database, with effective national alerting mechanisms, needs to be put in place. Members of the public, community centers, etc., can report missing children; these are initially investigated by the police in the source country, who can then activate in-country and cross-border alert requests through the centralized regional system, on the basis of their analysis of a missing child report. This model focuses specifically on cross-border trafficking of children.

The MCA program would implement and operationalize a regional system to address the issue is a coordinated manner. This regional CBCT response system would manage each child’s case from initial logging through to repatriation of a rescued child (Figure 11.3).

It is envisaged that this regional system would work as follows:

1. A secure, centralized server records missing (trafficked) children. Found children could also be recorded in this system. Alternatively, found children could be recorded in in-country systems which would be checked on an as-needed basis by the CBCT response system.

2. Web browser interfaces for the initial reporting, alert activation and management (by the police or other authorized agency), and the provision of updates relating to the initial search and to the status of the missing child. Even though a missing child may be reported via the web interface it must be reviewed (by the police) before it is confirmed and accepted as a valid record of a missing child.

3. Child records remain open on the system until such time as the child has been successfully repatriated (by which time the child may be over 18).

4. A database of alert recipients is maintained by a system coordinator, and for each missing child alert a schedule of alerts may be created by an authorized agent (for example, certain police officers who have the authority to issue an alert). In the first phase at least, alerting is IP-based, and may consist of:

b. RSS news feeds;

c. XML-based data feeds to partner systems. These may include broadcast media outlets, national/local missing persons systems, and networks such as the police and railway police in India.

IP-based alerting can be done by the centralized regional system hosted in any part of the world. However, if alerting is done using voice or SMS messaging then it should be initiated in-country for cost reasons. This would necessitate either (a) the mirroring of the cross-border alerting database in each of the three countries, with notifications sent from the locally mirrored sites; or (b) local alerting done by local agents or nodes in each of the countries. These local alerting nodes could receive the alert information by email, etc., and respond by sending an SMS broadcast using their own gateway software or by making phone calls.

5. Links will be provided to national child tracking systems in Nepal and Bangladesh (if/when these exist), as well as to other partner systems such as Homelink and the AP-NIC missing persons system) so that:

a. Data can be automatically transferred from these to the regional system if a missing child has already been recorded.

b. National/local partner databases can be searched for a reported missing child. Missing child searches could be implemented from/to in-country systems (such as Homelink, for example).

The MCA program needs to actively encourage potential partners to receive and act on the alerts, starting with the proposed pilot project districts. It is important to recognize that the regional system is not replacing the case management systems used by the police, child welfare service providers, helplines, shelter homes or any of the other stakeholders, nor is it replacing the national missing child/persons systems. It is a separate system which focuses on cross-border child trafficking, and in particular on the coordination of rescue and repatriation. A typical scenario for when a child is reported missing is presented in Figure 11.4.

The advantages of the centralized option are:

1. It is not dependent on the implementation of national missing child systems. The intervention still needs the support and cooperation of the authorities to succeed, but the technological system can be deployed independently of them. This is likely to result in faster implementation as well as better coordination of activities across the three countries.

2. Since the alert notifications are controlled centrally, the response to a missing child report can be coordinated and have a broad reach. It is possible, for example, to configure a notifications database to send alerts according to a predetermined schedule (for example, immediately to BGB in Bangladesh, to railway police and others along known transit routes in India after a period of number of hours, and later to trusted organizations operating in the likely destination cities).

3. As with Option 1, this may require the drafting and implementation of SOPs to handle the information flows and collaboration between governments. However, the information exchange is more likely to succeed if it is being coordinated at regional level.

4. The system will, over time, provide accurate data in relation to cross-border trafficking of children.

Some of the risks/disadvantages are:

1. Without in-country missing child systems or some mechanisms for effective, coordinated responses by the authorities in Nepal and Bangladesh, and without a national system in India, this model is limited in its capacity to distribute alerts amongst the police, border guards, railway police, etc.

2. The management and operation of the CBCT response system requires significant resources which the MCA program would have to provide.

3. There is a risk that the system is seen as a private initiative, which may inhibit the engagement by governments and participation by the State authorities.

4. The costs associated with the implementation of the regional CBCT response system are primarily dependent on the technological components used to build it, and where/how it is hosted. Taking the same approach as was taken for the national missing child tracking systems, it is expected that the TCO is in the order of $400,000 over the three years of the pilot phase.

Conclusions

The advance of technology and society brings with it, as has always been the case, both threats and opportunities; in discovering fire and using it to benefit there has always been the opportunity of threat, by use or malign use. We can extend this analogy to technology today, but there is clearly a need to address the ubiquity of access and mechanisms of application that technology provides. The United Nations, as a voice for the international community, articulates the rights to both information and to privacy, with an over-riding right to protection. This includes the right to information and awareness about issues, an issue addressed by Hick and Halpin (2001), amongst others. Whilst the case study presented earlier illustrates the technical challenges, and the equally complex social issues, that need to be addressed simultaneously in addressing the technical challenges that have to be addressed; the case study illuminates the issues and might viewed as an exemplar of the many other technical issues that require solutions when looking at emerging technologies child exploitation and possible use of ICT for protection. The conclusion of the study notes that

Technological systems to address the issue of cross-border trafficking must be viewed as only part of the solution. For them to be effective, the necessary legal and institutional arrangements must be put in place and political and administrative arrangements must exist to make them work.

This final point on the legal frameworks, cross-border working, and an explicit application of the international conventions, such as the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, seem at this stage the most difficult to address and yet the most important, if there is to be an effective adoption of protection of children; the technology can offer answers, the legislation and political will must facilitate it.